Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting

from High Schools

Ilenia Fronza

1 a

, Luis Corral

2 b

, Gennaro Iaccarino

3

, Lucia Bartoli

3

and Claus Pahl

1 c

1

Free University of Bozen/Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy

2

ITESM Campus Queretaro, Queretaro, Mexico

3

I.I.S.S. “Galileo Galilei’, Bolzano, Italy

Keywords:

Work from Anywhere, WFA, WFX, Skills, K-12, High Schools.

Abstract:

The world of work-from-home (WFH) and work-from-anywhere (abbreviated WFX or WFA) grew more than

ever during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many companies are now planning on permanently allowing WFX,

with subsequent demand for specific skills. It is crucial to foster these skills in high schools, as students may

enter the job market without attending University. Up-to-date analysis of the current situation is missing to

align supply and demand by enabling educators to set goals and strategies to train students so that they will

be able to mesh into a WFX setting. To address this issue, we collected complementary data using a case

study (23 students), a questionnaire (616 students), and interviews with professionals and practitioners of the

software development sector. Results suggest that information management, communication skills, autonomy,

and resourcefulness are key competencies that enable professionals to succeed in a WFX environment. How-

ever, students feel less prepared in terms of communication skills; moreover, they lack time management and

autonomy skills. Based on our results, we highlight recommendations for educational practice that educators

can use in curriculum building to fill the gaps that emerged in this study to assure the effective development of

the skillset demanded by current and future WFX conditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The adoption of Work-From-Home (WFH) policies

grew in the 2000s (Sako, 2021) and was followed by

Work-From-Anywhere (abbreviated WFX or WFA),

which provided employees with greater geographic

flexibility and autonomy in choosing spaces, times,

and tools (Choudhury et al., 2019; Sako, 2021). Dur-

ing pandemic conditions, several sectors leveraged

these policies for business continuity. These changes

occurred well beyond the working settings where

these policies were already in place and have involved

the educational context at every level.

After the most critical emergency conditions

passed surveys reveal workers’ desires to continue

with the new working setting, and some companies

are transitioning toward a permanent WFX model

(Drera, 2021). Based on these considerations, strong

demand for WFX skills (Paasivaara et al., 2013; Pros-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0224-2452

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9253-8873

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9049-212X

sack, 2020) is expected for the next future in the

job market. It is crucial to foster these skills in

high schools (Fronza et al., 2022), as students may

enter the job market without attending University.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided the chance

to work in this direction. Indeed, school digitiza-

tion accelerated, and students needed to organize their

work autonomously by going beyond the concept of

“school hours” and focusing instead on the achieve-

ment of the objectives (in a WFX style). However,

up-to-date analysis of the current situation is missing

to align supply (from schools) and demand (of the job

market), which would enable educators to set goals

and strategies to train students so that they will be able

to mesh into a distributed, WFX setting.

This work aims at providing an overview of the

current state of WFX skills supply and demand. To

this end, we collected complementary (qualitative and

quantitative) data using a mixed-method triangula-

tion design in which we combined a case study (with

23 high school students), a questionnaire (with 616

high school students), and interviews with ten indus-

try practitioners of the software development sector.

Fronza, I., Corral, L., Iaccarino, G., Bartoli, L. and Pahl, C.

Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting from High Schools.

DOI: 10.5220/0010984300003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 327-337

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

327

Results suggest that a compound of soft and hard

skills (some of them already visualized and required

before the pandemic) are considered key enablers and

assumed “givens” for those professionals joining and

participating in global and WFX teams. Among these

skills, students feel less prepared in terms of com-

munication skills. Particular attention receives self-

motivation: WFX workers are expected to be au-

tonomous and self-driven, but our results evidence

lack of time management and autonomy skills among

students.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Sec-

tion 2 introduces related work; Section 3 describes

our research method and our data collection strategy.

Results are shown in Section 4 and discussed in Sec-

tion 5. Section 6 draws conclusions and suggest areas

for future work.

2 RELATED WORK

Remote working involves working in a defined and

stable place (e.g., home) with an appropriate desk,

optimal Wi-Fi, and a fixed schedule. It arguably be-

gan with the Work-From-Home (WFH) policies in the

1970s to counteract rising gasoline prices (Choud-

hury, 2021); in 1983, M.H. Olson (Olson, 1983)

found that the individuals who worked at home suc-

cessfully were self-motivated and self-disciplined in-

dividuals who made the arrangement either because

of family requirements or because they preferred few

social contacts beyond family. In the 2000s, the adop-

tion of WFH increased in several sectors thanks to

digital technology (e.g., faster and cheaper comput-

ers, stable broadband Internet, video chat platforms,

and desktop virtualization) (Sako, 2021). Research

showed WFH performance benefits; for example, a

2015 study found increased productivity (by 13%)

for the employees who chose WFH (Bloom et al.,

2015). Consequently, some companies launched

Work-From-Anywhere (WFX) programs, i.e., they

moved toward greater geographic flexibility.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these

changes already underway: many companies imple-

mented a working management philosophy based on

giving people flexibility and autonomy in choosing

spaces, times, and tools, which also means greater re-

sponsibility when talking about results. WFX does

not mean simply working from a distance, i.e., it can

include WFH, but it is more than that (Softtek, 2020):

workers can organize the day by combining a time

for private life and one for work-life, based on mu-

tual participation and trust (Stamenova, 2021; Soft-

tek, 2020) between the employer and the collabora-

tors. Even though availability needs to be granted

(e.g., to discuss the status of ongoing projects), what

matters is meeting the objectives (Softtek, 2020) at

the pre-established times. This encompasses a wider

vision of the whole picture: a new organization of the

working setting (goals, schedule, teamwork, collabo-

ration, accomplishment, and accountability) that mo-

tivates a true shift in the working paradigm towards

empowering employees to understand clearly the goal

at hand, analyzing resources (tools and time), collabo-

rating with others and delivering results (Smart Work-

ing Observatory, 2020).

In 2021, Barrero et al. developed systematic ev-

idence about whether remote work will stick after

the pandemic, why, and some of its economic and

societal implications: desires to continue with re-

mote work emerge across groups defined by age, ed-

ucation, gender, earnings, and family circumstances.

Moreover, most workers express a willingness to ac-

cept sizable pay cuts in return for the option to work

from home two or three days a week (Barrero et al.,

2021). In a 2021 survey (Buffer, 2021) with a total

of 2300 respondents, 94% percent of the respondents

who started working remotely as a result of the pan-

demic selected that they would like to work remotely,

at least some of the time, for the rest of their career;

that number increased to 99% for people who were

remote workers before COVID-19. Moreover, 46%

said that their company was planning on permanently

allowing remote work. M. Sako (Sako, 2021) foresees

a hybrid model combining remote and in-office work-

ing: workers will balance tasks that can be carried out

remotely (e.g., writing reports) and tasks that are bet-

ter carried out in social spaces (e.g., brainstorming).

In this regard, Smite et al. identified the future chal-

lenge of “identifying the must-happen in-the-office or

in-collocation practices, ceremonies, and events that

will help maintain the organizational culture” (Smite

et al., 2021). Offering employees customized work-

ing styles seems to be the winning strategy to attract

talents (Kelly, 2021). At the moment, the strategy

is not uniform among tech companies. For instance,

Facebook, Uber, and Microsoft are pushing for a pre-

pandemic model, at least in a short period. Others

(such as Twitter and Spotify) are transitioning toward

a permanent WFX model (Drera, 2021).

WFH determined changes and novelties of work-

ing routines and practices; for example, daily rhythm

is more flexible and self-imposed (Smite et al., 2021).

Moreover, WFH comes with a list of issues, such as

not being able to unplug, loneliness, difficulties with

collaboration and communication (Buffer, 2021). As

a consequence, specific skills are needed to succeed in

this working setting, as reported by the research liter-

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

328

ature in Global Software Engineering (i.e., a common

practice in software development teams) (Monasor

et al., 2010; Richardson et al., 2010; Swigger et al.,

2010). These skills include strong written communi-

cation, adaptability, time management, collaboration,

focus, working in culturally diverged teams, and using

collaborative technologies (Paasivaara et al., 2013;

Prossack, 2020). Notably, most of these are soft skills

(Paasivaara et al., 2013). Having an overview of the

current state of WFX skills supply and demand would

allow educators to set goals and strategies to train stu-

dents so that they will be able to mesh into a dis-

tributed, WFX setting.

3 METHOD

In this study, we will answer the following questions:

• RQ1. How ready are high school students for

WFX?

– RQ1.1. How do students perceive WFX?

– RQ1.2. What WFX skills do students have?

• RQ2. What skills do employers think are needed

for WFX?

• RQ3. How aligned are the supply and demand of

WFX skills?

A mixed-method triangulation design has been

used in this study to obtain different but complemen-

tary data (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). As shown in

Figure 1, we collected and analyzed quantitative and

qualitative data separately and then merged the differ-

ent results. Concurrent, but separate, collection and

analysis of quantitative and qualitative data included

the following methods: 1) case study, involving 23

students of a CS high school (Section 3.1), 2) ques-

tionnaires, involving 616 students attending a range

of types of high schools (Section 3.2), and 3) inter-

view of ten professionals in industry/productive sec-

tors in the area of software development, holding roles

of recruitment, talent detection, talent acquisition, and

front-line people leadership (Section 3.3).

Figure 1: Triangulation design: convergence model

(adapted from Creswell and Cresswell, 2017).

3.1 Case Study

The study context is a business simulation project in

a fifth-year class of a CS high school in Bolzano,

Italy. A total of 23 students (21 M, 2 F; 18-19 years

old) was involved. The project simulated 15 profes-

sional working days to implement a web-based ap-

plication commissioned by a customer (i.e., the lab

technicians), who asked for a system with a dynamic

database to manage the material in the chemistry and

microbiology laboratories.

A simulation project has been chosen because of

its ability to enhance skills, including strategy devel-

opment, time management, team building, negotia-

tion skills, decision making, and team-working (Asiri

et al., 2017; Xu and Yang, 2010). To obtain a di-

dactic transposition (Hazzan et al., 2010) of a profes-

sional context, we adopted a pseudo-business struc-

ture, with reference figures (chosen by the students

upon teacher’s approval) and an organizational plan.

The activity was carried out partly remotely and partly

on-site; in both cases, the adoption of WFX working

practices (i.e., time management, sharing documenta-

tion, work organization with the other groups) was en-

couraged. All the project documentation is available

online (www.iisgalilei.eu/cmb/documentazione/).

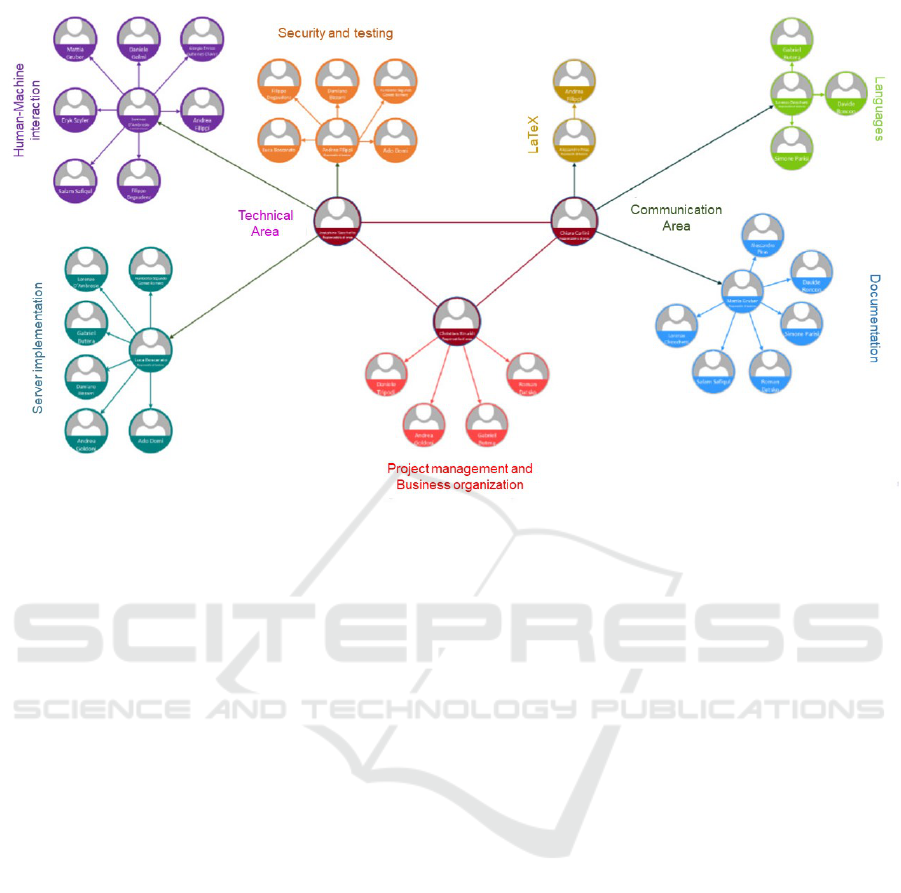

As shown in Figure 2, students were divided into

the following two areas: the technical area (dedi-

cated to project development) and the communica-

tion area (focusing on documentation, communica-

tion, and graphic/web layout). Each area was coor-

dinated by a group leader chosen by the CS teacher

among the most motivated students in the group. Each

area was divided into smaller groups according to the

tasks assigned; for example, the technical area in-

cluded smaller groups that worked on security/testing,

human-machine interaction, and server implementa-

tion. Each student could choose the area and the

group membership according to their characteristics,

inclinations, and tasks in the area. We used self-

selected teams (i.e., students chose the team) because

this approach is more efficient for short-term projects

(Bacon et al., 1999). Each sub-group had a student

leader, who was chosen by the team and interacted

with the other groups and with the area leader.

Since it was a simulation project, we attempted

to promote knowledge and experiences that emu-

late, methodologically and practically, the common

environment of the software industry (Corral and

Fronza, 2018). Moreover, we aimed at facilitating the

achievement of the objectives. Based on these con-

siderations, the teacher proposed and agreed on a se-

ries of daily objectives for both groups and individual

participants. Then, the teacher and the leaders regu-

Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting from High Schools

329

Figure 2: Organizational chart of the case study.

larly verified the progression of the work and the ac-

tual achievement of the objectives. Throughout the

process, we distributed the following daily question-

naire (using an online form) to track the progress of

the WFX experience in terms of work hours, achieve-

ment of goals, self-perception in the team, and issues

encountered:

1. Indicate the time slots of the day in which you

worked best in the remote team.

2. Indicate the time slots of the day in which you

worked best individually.

3. In your opinion, did your team achieve the goals?

[yes; no]

4. Did you find it difficult to achieve the goals? [yes;

no]

5. Did you feel being appreciated during the project?

[Likert scale 1-10]

6. How difficult were the following activities? [area

management; time management; group manage-

ment; identify critical issues/problems; solve crit-

ical issues/problems]

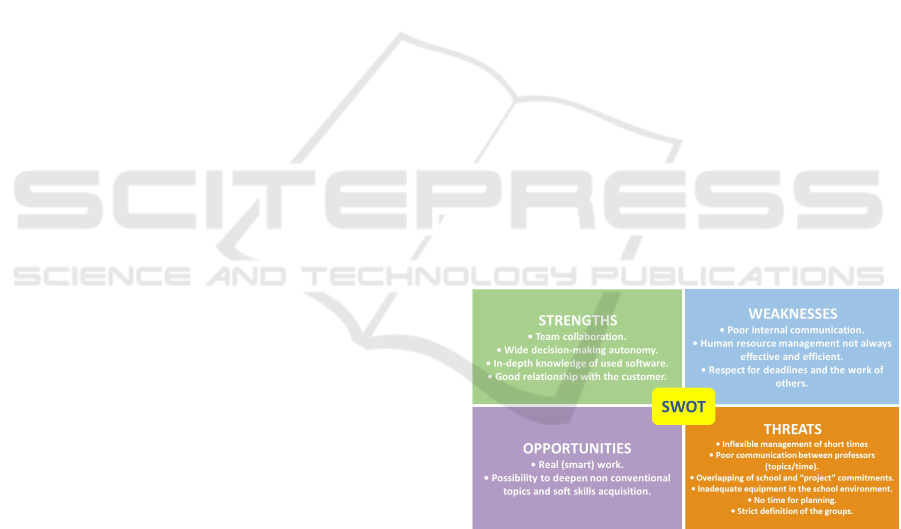

At the end of the activity, students wrote a final

report focusing on their opinion on the project. More-

over, they identified the Strengths, Weaknesses, Op-

portunities, and Threats of the activity (i.e., SWOT

analysis). These considerations were subsequently re-

ceived and discussed by the class teacher.

3.2 Questionnaire

We distributed a questionnaire among students of dif-

ferent high schools all over Italy to assess the acquisi-

tion level of digital skills after distance learning. The

questionnaire was developed following the approach

adopted by (Park and Han, 2019) and included five

questions. The first three demographic questions col-

lected information about the respondent’s characteris-

tics (i.e., city, grade, age range). Then, the following

main questions were asked:

1. Since resuming in-person (even partially) classes,

how much are you using the following tools for

studying reasons? [Never, A little (1-2 times a

month), Often (1-3 times a week), Always (at

least 4 times a week)]

• Devices (PC, Notebook, Smartphone, Tablet)

• Social Network (Instagram, Facebook,

LinkedIn, YouTube, Linknow, Google Plus,

Twitter)

• Videoconferencing tools (Zoom, MS Teams,

Google Meet, Discord)

• Storage/sharing tools (Google drive, One drive,

N-drive, Dropbox, Apple I-cloud, e-Register, e-

Mail)

2. How do you assess your skills in the following

areas? [None, Poor, Good, Excellent]

• Ability to find information (web, wiki,

YouTube, social networks)

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

330

• Ability to create documents (MS Word, Excel,

PowerPoint, keynote, Office 365, Google doc-

uments)

• Ability to manage materials in a systematic

manner (digital notes, folders, papers)

The questionnaire was distributed using an online

form. We followed legal requirements and ethical

codes of conduct of child participation in research

(EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014). For

example, we collected informed consent, asked for

voluntary participation, and informed the respondents

about the confidential treatment of data.

3.3 Interview

Research interviews were selected as a data collec-

tion method thanks to their possibility to engage in

deeper conversations with professionals and practi-

tioners. Besides discovering what skills are valuable

in the current remote working settings, interviews

allowed us to elaborate deeper on the obtained re-

sponses and relate them better to the current working

settings (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). This latter

idea is also paramount in this data collection strategy:

responses delivered by industry interviews do not re-

fer to a development outlook or a series of competen-

cies to grow: responses commonly reference back to

a current working context, situations that are happen-

ing now in a productive setting and that, as such, rep-

resent a series of skills that employers and companies

are already looking for or requiring.

Each semi-structured interview (Wohlin et al.,

2012) involved the same interviewer together with

one interviewee at a time and lasted between 40 and

50 minutes. In the first part of the interview, we

obtained consent from the interviewee and informed

them about the confidential treatment of collected

data. The interview was conducted remotely through

an online video-conferencing platform and included

the following two questions (excluding elaboration or

follow-up questions):

• What are the skills or competencies you are look-

ing for in candidates or colleagues to engage bet-

ter in a WFX environment?

• Which of those skills are new, that is, you pre-

viously did not consider them as core competen-

cies?

Ten industry representatives were available for an

interview; this number respects the suggested dimen-

sion of a qualitative sample to collect expert views,

i.e., an average of 5 with a range of 2 to 8 (Benzo

et al., 2017). The profiles of the interviewees vary

from roles of recruitment, talent acquisition, front-

line people leadership, and technical leadership. The

profiles of the companies involved are mostly tech-

nology, spanning from software development to arti-

ficial intelligence services, hardware, infrastructure,

and education. Companies interviewed are based out

in Austria, Poland, Mexico, the United States, and

Indonesia. The names of the companies were kept

anonymous to ensure transparency and confidential-

ity of the results.

4 RESULTS

In this section, we provide the answers to each re-

search question.

RQ1. How Ready Are High School Students for

Smart Working? RQ1.1. How do students perceive

WFX? During the case study, as requested by the cus-

tomer, the students designed and implemented a web-

based application to manage all the material in the

chemistry and microbiology laboratories. The appli-

cation is based on a LAMP architecture (i.e., Linux,

Apache, MySQL, PHP services). The application is

browser-based and accessible via HTML and CSS.

All the objectives proposed during the project have

been achieved; the application has been tested and

is correctly functioning. Figure 3 shows the SWOT

analysis completed by the students at the end of the

activity.

Figure 3: SWOT analysis completed by the students at the

end of the case study.

Focusing on the identified opportunities, the stu-

dents considered the initiative a good chance to

deepen topics treated only theoretically and briefly

during school lessons; moreover, they felt they could

improve their soft skills, which was considered im-

portant for their future. Among the strengths of

the activity, students appreciated team collaboration,

mentioned that they found short-term goals challeng-

ing, and found it very useful to obtain teacher feed-

back regularly. The analysis of the daily question-

Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting from High Schools

331

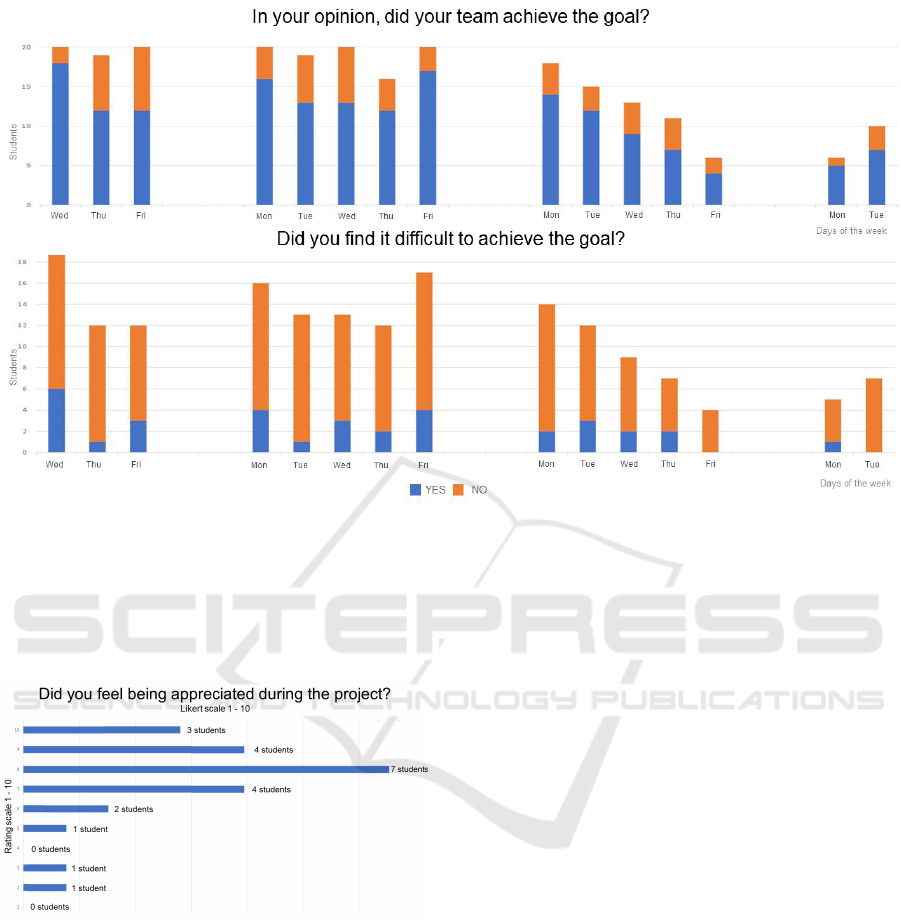

Figure 4: Daily questionnaire: difficulty and achievement of the daily goals.

naires (Figure 4) shows that majority of the students

reported that they achieved the goals every day. How-

ever, achieving these results was difficult for most of

them. Furthermore, students felt being appreciated

during the activity (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Degree of perceived appreciation.

Students enjoyed autonomy in the decision-

making process (which requires being responsible)

and the possibility to learn digital skills and new tools

for collaborative work. However, weaknesses and

threats highlight several issues in the existing school

system. For example, school equipment is not always

up to the demands, there is a lack of time manage-

ment between different disciplines, and inadequate

communication between teachers, who do not always

manage to work together to achieve common goals.

Moreover, according to the participants, it was dif-

ficult to stop using the typical school work model,

where productivity is often condensed into the morn-

ing hours. In this regard, the analysis of the daily

questionnaires shows that students worked best in

the 8:00-12:00 time slot (Figure 6), both in groups

and independently. Therefore, students maintained

their regular school habits even though they could au-

tonomously organize their workday in a WFX style.

These considerations were subsequently received

and discussed by the class teacher, who strongly

agrees on the criticisms set out by the students and

the need for better planning of time and content as

a teaching model for the future. During the discus-

sion with students, another interesting area of reflec-

tion emerged: the approach used in the case study was

easier to accept and implement in families where par-

ents are used to WFH or WFX. Instead, the new work-

ing style was more difficult to implement where par-

ents have a fixed schedule and do not work remotely,

possibly indicating that the concept of flexibility and

WFH/WFX has yet to enter into common habits, with

all its pros and cons.

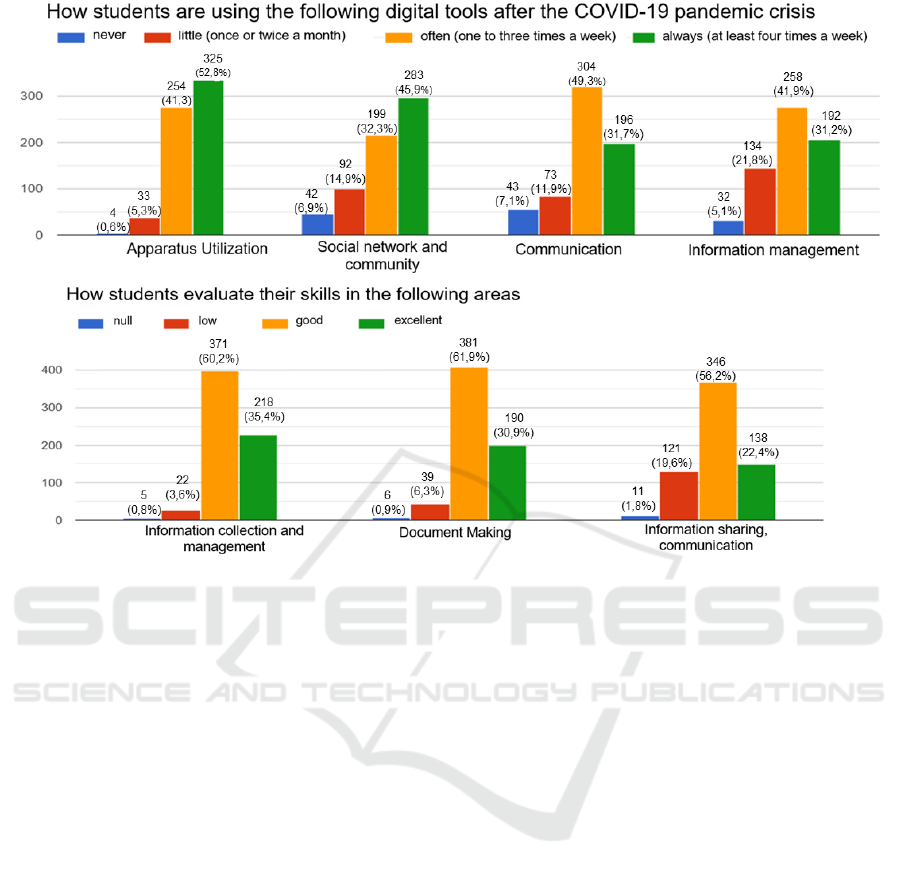

RQ1.2. What WFX skills do students have? As

shown in Table 1, the questionnaire received 616 an-

swers from students aged 14-19 (95.6%) and students

aged 20 or over (4.4%). Respondents had the fol-

lowing backgrounds: technical (63.5%), arts, classi-

cal, scientific, foreign language (20.3%), vocational

(14.8%), and others (1.4%).

Regarding the usage of digital tools (question 1),

Figure 7 shows that only 5-6% of students do not

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

332

Figure 6: Time slots of the day in which students worked best in the remote team and autonomously.

Table 1: Questionnaire: respondents’ age.

14-16 years 17-19 years >20 years

49.3% 46.3% 4.4%

know the indicated tools, and 10% rarely use them.

About 41-42% use the tools sometimes during the

week and 40% almost daily for school activities.

Most of the respondents use communication tools one

to three times a week, while 45.9% use social network

and communication tools at least four times a week.

Most students never/rarely use information manage-

ment tools. When asked to self-assess their skills

(question 2), even though information and manage-

ment tools are the least used, only a few respondents

have no or low information collection and manage-

ment skills (1-4% as shown in Figure 7). The infor-

mation sharing and communication skills are those in

which students feel least prepared (20-22%).

RQ2. What Skills Do Employers Think Are

Needed for WFX? The responses delivered by inter-

views converged on mentioning a collection of skills

that could be already identified even before the pan-

demic conditions. Due to the informal format of

the interview and the structure in open-ended ques-

tions, we grouped the answers in concepts, establish-

ing clusters for similar ideas or synonyms (for ex-

ample, self-motivation included other responses like

“self-determination” or “self-driven attitude”). The

following list displays the skills mentioned by respon-

dents sorted by frequency.

• Self-motivation (6): Understood as the ability to

understand business goals and deliver to them.

Self-motivation implies overflowing that under-

standing into the day-to-day way to work, es-

tablishing clear personal goals and working to-

ward them without the need of being constantly

reminded about goals, or working in co-location

with other colleagues that share the same goals.

• Communication (5): In a distributed work envi-

ronment, communication is of utmost importance

to maintain a continuous dialog with other team

members, promote teamwork and collaboration,

understand and convey goals and objectives, re-

port progress, explain designs, and, very interest-

ingly, maintain the morale of a team.

• Autonomy (5): The ability to learn indepen-

dently, cover independently learning curves, un-

derstand goals and execute tasks with a minimum

guide. In particular, self-learning is required since

employees learn a lot while working hand in hand

with colleagues; now, they have to learn on their

own.

• Time Management (4): Work schedule inter-

preted as a time frame with a start time in the

morning and end time in the afternoon is no longer

in place. It was expressed a particular interest

in attracting talent that can manage time indepen-

dently and deliver to goals regardless of the num-

ber of hours invested and the schedule followed.

Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting from High Schools

333

Figure 7: A synthesis of the questionnaire replies.

• Curiosity (1): The capacity of employees to ini-

tiate action, having an exploring attitude towards

uncertain or ambiguous conditions.

• Endurance (1): Also referred to as resilience, the

capacity of employees to overcome failure, deal

with ambiguity, manage frustration, be persistent

and establish the emotional temper that is required

to work in isolated conditions.

• Position Fit (1): Alignment between personal

goals and company goals, that would bring as a

consequence a better understanding of goals and

better motivation to deliver.

Concerning the second question, we could ob-

serve an almost unanimous convergence towards ex-

pressing that the above-mentioned skills are not any-

more a desired characteristic or a professional plus.

Instead, respondents now consider these skills as ba-

sic qualifications, and without them, it would be diffi-

cult to succeed in current professional environments.

However, interviewees stressed that skills like time

management or autonomy, commonly required in in-

terviews, became particularly relevant in current busi-

ness conditions.

RQ3. How Aligned Are the Supply and Demand of

WFX Skills? To answer RQ3, we bring the separate

results together, comparing and contrasting (Creswell

and Creswell, 2017) the vision of three different set-

tings, i.e., the personal opinion of several students, the

perception of participants of a simulated working set-

ting, and the reflections of practitioners currently part

of the productive sector. Indeed, it is of particular in-

terest to identify elements that are relevant depending

on the environment, and also to discover convergent

elements.

According to the collected data, the educational

environment focuses on outlining elements of com-

puter and technological literacy by, for example, list-

ing tools that are important for seamless integration in

a WFX environment (hardware and software tools and

a good command of their use). Several of the men-

tioned tools are specifically designed and distributed

to facilitate communication (social media tools) or

collaboration (Google Documents, Wikis). Profes-

sional respondents take for granted technological lit-

eracy and focus their attention on other job-specific

competencies. However, information management

tools are never or rarely used by most students.

In contrast, the simulated work environment con-

verged in several traits to answers given in the produc-

tive working setting. For instance, teamwork and col-

laboration are highly valued by the two sources. Flex-

ibility in the schedule and time invested in the work is

highly valued in the educational setting and also men-

tioned by practitioners bound in the concept of time

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

334

management. Communication skills, autonomy, and

resourcefulness are elements mentioned both by the

student and professional setting as key competences

that enable professionals to succeed in a remote work

environment. However, students feel less prepared in

terms of communication skills; moreover, poor inter-

nal communication is listed among the weaknesses in

the SWOT analysis at the end of the case study. Par-

ticular attention receives self-motivation: WFX work-

ers are expected to be autonomous and self-driven so

that they can lead and deliver in an environment of

little personal interaction with other peers, or without

the need of being supervised closely by managers. In

this regard, the case study participants included the

possibility of flexible time-management among the

opportunities provided by the activity; however, stu-

dents continued to work in the morning (as if they

were at school) without taking full advantage of this

possibility. This result evidences a lack of time man-

agement or autonomy skills, which are considered

particularly relevant by the interviewed industry rep-

resentatives.

5 DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest a core of skills needed to adapt

and contribute in a WFX setting. There are relevant

coincidences between the experience reported by stu-

dents and the expectations outlined by industry prac-

titioners. Information management, communication

skills, autonomy, and resourcefulness are considered

key WFX enablers competencies. However, students

feel less prepared in terms of communication skills

and lack time management and autonomy skills.

Based on our results, we highlight a set of rec-

ommendations for educational practice that educators

can use in curriculum building to fill the gaps that

emerged in this study. First, current timetable man-

agement in the school does not seem to foster time

management and autonomy skills. Indeed, the school

timetable is generally strict: each subject has a spe-

cific number of time slots, not always functionally

distributed. Furthermore, the high number of subjects

and their alternation during the morning (or day) pro-

duce general fragmentation of knowledge and skills,

instead of favoring their connection. The same rigid-

ity applies to the clear separation between school time

and free time, which are in turn non-communicating

areas. This time management model is likely to reflect

on how these future workers will cope with working

time. Our suggestion is to involve students in activi-

ties in which the daily routine is interrupted for short

periods and completely disrupted. These activities

would represent a total subversion of time manage-

ment and foster productive autonomy through short-

term planning in a scenario where the teacher super-

vises, detects, and rewards the work of individuals

and groups.

Second, instructors should dedicate space to prac-

tical involvement through hybrid (i.e., partially on-

site, partially remote) or fully-remote projects. These

activities may start laying foundations on WFX criti-

cal skills before students integrate into the labor mar-

ket. Third, instructors need to carefully understand

how to incorporate these activities, either designing

a specific curriculum to teach enabler concepts or

adapting the practice on current subjects to incorpo-

rate practices. As students grow in age and matu-

rity, experiences that are closer to an industrial setting

should be incorporated, as exemplified by simulated

work environments. Finally, high schools should keep

up embracing the adoption of digital and collabora-

tive tools just like the professional and productive

sector. With the pandemic conditions, this adoption

has been promoted and accelerated; however, getting

back to “normal” may cause losing momentum on the

paradigm shift and pivotal changes that remote work

promoted in schools. With a positive adoption of the

best practices of remote work, and taking the best of

face-to-face interactions at school, students will be

both more experts in the use of digital tools that en-

able WFX, while exploiting better the social and per-

sonal competencies that the productive sector is and

will be looking for. Through the wise mix of the two

strategies, and through the promotion of simulated

WFX work environments, schools have now an un-

paralleled opportunity to prepare future WFX work-

ers.

6 CONCLUSION AND

LIMITATIONS

In this paper, we described an initial outline of the

current needs expressed by educational and produc-

tive sectors concerning abilities that are expected and

desired in WFX workers. Based on this core, we fos-

ter the discussion on how to adapt strategy and cur-

riculum to educate students in the theory, practice,

and technology that foster the ability to have a seam-

less integration into a WFX setting. We acknowledge

that the works presented by this paper may have some

limitations. In the following, we discuss them and

elaborate on how these limitations do not threaten the

strength of our results:

• The first two sources of information are the per-

sonal opinion and subjective views of school stu-

Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting from High Schools

335

dents, concerning their regular interaction, or their

experience in a simulated work. Subjectivity may

be seen as a threat to the validity of the results;

nevertheless, we believe that in this case, the per-

sonal view and experience provided by partici-

pants is precisely the subject matter of discussion.

Acquiring information about the insight and ex-

ecuting the necessary analysis to extract the in-

sight is outlined as a high-level goal, so working

directly with subjects and understanding their ex-

perience is a critical foundation of this work.

• The number of interviews with employers is

rather small with respect to the number of stu-

dents surveyed in the other two settings. We un-

derstand that qualitative research tends to have

smaller samples as the emphasis is placed on cap-

turing data in depth. A suggested dimension of

a qualitative sample to collect expert views is an

average of 5 with a range of 2 to 8 (Benzo et al.,

2017), and the viewpoint and insight obtained

from them, shed light on the practitioner’s per-

spective on the matter. Moreover, the voice of the

experts permits us to understand how these per-

spectives translate into job requirements, job de-

scriptions, or skills that are searched in the labor

market.

• Another limitation associated with interviews

with employers is a continuous request to keep

anonymous their names and the names of the com-

panies they are affiliated to. These requests come

from the fact that private industry is not always

willing to share practices, criteria, and informa-

tion that may represent a competitive advantage in

an aggressive labor market, and anonymity obfus-

cates information associated with a specific com-

pany. Although the interviews spanned global,

high technology companies, their request to re-

main anonymous does not permit to show evi-

dence on this claim.

• Larger samples are needed to confirm and gener-

alize the results and limit the validity threats con-

nected with the reliability and validity of our in-

struments. Moreover, multiple iterations of pilot-

ing and testing will allow us to develop valid and

reliable instruments.

• Another limitation is represented by the need for

teacher training, as teachers need to be trained to

apply the given recommendations effectively.

Educators can use our results as a baseline and

entry point to map out competencies, design curricu-

lum, and teach courses that assure the effective de-

velopment of the skill set demanded by current and

future remote working conditions. High education

time frames can be leveraged to enhance the educa-

tional experience to prepare professionals more capa-

ble to incorporate themselves into a WFX environ-

ment. Other elements of discussion remain open:

items like work safety, information security, stress

that can be associated with the fact of being con-

tinuously connected, fatigue associated with the use

of technological tools, privacy, and employee’s well-

being are ideas that need to be explored when dis-

cussing how to educate and prepare future WFX

workers.

REFERENCES

Asiri, A., Greasley, A., and Bocij, P. (2017). A review of

the use of business simulation to enhance students’

employability (wip). In Proceedings of the Summer

Simulation Multi-Conference, SummerSim ’17, San

Diego, CA, USA. Society for Computer Simulation

International.

Bacon, D. R., Stewart, K. A., and Silver, W. S. (1999).

Lessons from the best and worst student team expe-

riences: How a teacher can make the difference. Jour-

nal of Management Education, 23(5):467–488.

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., and Davis, S. J. (2021). Why

working from home will stick. Technical report, Na-

tional Bureau of Economic Research.

Benzo, R., Mohsen, M. G., and Fourali, C. (2017). Market-

ing research: planning, process, practice. Sage.

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., and Ying, Z. J. (2015).

Does working from home work? evidence from a

chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Eco-

nomics, 130(1):165–218.

Buffer (2021). The 2021 state of remote work. https:

//lp.buffer.com/state-of-remote-work-2020. Last ac-

cessed: February 15, 2022.

Choudhury, P., Larson, B., and Foroughi, C. (2019). Is it

time to let employees work from anywhere. Harvard

Business Review, 14.

Choudhury, P. R. (2021). Our work-from-anywhere future.

Defense AR Journal, 28(3):350–350.

Corral, L. and Fronza, I. (2018). Design thinking and ag-

ile practices for software engineering: an opportunity

for innovation. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual

SIG Conference on Information Technology Educa-

tion, pages 26–31.

Creswell, J. W. and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research de-

sign: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods

approaches. Sage publications.

Drera, S. (2021). Is work-from-anywhere (wfa) here to

stay? Linkedin, https://tinyurl.com/pv8xbtdd. Last

accessed: February 15, 2022.

EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014). Child

participation in research. https://fra.europa.eu/en/

publication/2014/child-participation-research. Last

accessed: February 15, 2022.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

336

Fronza, I., Corral, L., Wang, X., and Pahl, C. (2022).

Keeping fun alive: an experience report on running

online coding camps. In Proceedings of the 44nd

International Conference on Software Engineering:

Software Engineering Education and Training (ICSE-

SEET ’22), New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Hazzan, O., Dubinsky, Y., and Meerbaum-Salant, O.

(2010). Didactic transposition in computer science ed-

ucation. ACM Inroads, 1(4):33–37.

Kelly, J. (2021). Smart companies will win the war for tal-

ent by offering employees uniquely customized work

styles. Forbes, https://tinyurl.com/3asxn9cy. Last ac-

cessed: February 15, 2022.

Monasor, M. J., Vizca

´

ıno, A., Piattini, M., and Caballero,

I. (2010). Preparing students and engineers for global

software development: A systematic review. In 2010

5th IEEE International Conference on Global Soft-

ware Engineering, pages 177–186.

Olson, M. H. (1983). Remote office work: Changing

work patterns in space and time. Commun. ACM,

26(3):182–187.

Paasivaara, M., Lassenius, C., Damian, D., R

¨

aty, P., and

Schr

¨

oter, A. (2013). Teaching students global soft-

ware engineering skills using distributed scrum. In

2013 35th International Conference on Software En-

gineering (ICSE), pages 1128–1137.

Park, M. and Han, T. I. (2019). A study on digital ability

change after the smart worker education of the prime-

aged learner. International Journal of Information and

Education Technology, 9(4):257–262.

Prossack, A. (2020). 5 must-have skills for remote work.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashiraprossack1/2020/

07/30/5-must-have-skills-for-remote-work/?sh=

642d20df33c4. Last accessed: February 15, 2022.

Richardson, I., Moore, S., Malone, A., Casey, V., and

Zage, D. (2010). Globalizing software development

in the local classroom. In IT Outsourcing: Concepts,

Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, pages 1534–

1556. IGI Global.

Sako, M. (2021). From remote work to working from any-

where. Commun. ACM, 64(4):20–22.

Smart Working Observatory (2020). Smart work-

ing. https://www.osservatori.net/en/research/

active-observatories/smart-working. Last accessed:

February 15, 2022.

Smite, D., Moe, N. B., Klotins, E., and Gonzalez-

Huerta, J. (2021). From forced working-from-home

to working-from-anywhere: Two revolutions in tele-

work. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.

08315. Last accessed: February 15, 2022.

Softtek (2020). Smart working: Much

more than telework. https://softtek.eu/

en/tech-magazine-en/innovation-trends-en/

smart-working-mucho-mas-que-teletrabajo/. Last

accessed: February 15, 2022.

Stamenova, A. (2021). Smart working: The

agility and flexibility enterprises need.

https://www.lumapps.com/blog/digital-workplace/

smart-working-definition-benefits-tools/. Last

accessed: February 15, 2022.

Swigger, K., Brazile, R., Serce, F. C., Dafoulas, G., Al-

paslan, F. N., and Lopez, V. (2010). The challenges

of teaching students how to work in global software

teams. In 2010 IEEE Transforming Engineering Edu-

cation: Creating Interdisciplinary Skills for Complex

Global Environments, pages 1–30. IEEE.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., H

¨

ost, M., Ohlsson, M. C., Reg-

nell, B., and Wessl

´

en, A. (2012). Experimentation in

software engineering. Springer Science & Business

Media.

Xu, Y. and Yang, Y. (2010). Student learning in business

simulation: An empirical investigation. Journal of Ed-

ucation for Business, 85(4):223–228.

Work-From-Anywhere Skills: Aligning Supply and Demand Starting from High Schools

337