Using Cybersecurity Exercises as Essential Learning Tools in Universities

R

˘

azvan Deaconescu

1 a

, Andra B

˘

alt

,

oiu

2 b

, Tiberiu Georgescu

3 c

and Alin Puncioiu

4

1

University Politehnica of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

2

University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

3

Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania

4

Technical Military Academy “Ferdinand I“, Bucharest, Romania

Keywords:

Cybersecurity, Capture-the-flag, Contests, Education.

Abstract:

Capture-the-flag (CTF) contests play a well-established role in the cybersecurity culture, being at once skill-

testing grounds and community-building platforms. While these contests provide education benefits, their

adaptation to academic objectives is not straightforward, since the competitive nature of CTFs makes them

more appropriate for knowledge evaluation than acquisition. In this paper we present the preparing, deploying

and evaluating a cybersecurity exercise for university students. Our work aims to stimulate students for a career

in cybersecurity, evaluate their experience and collect feedback. We detail our experience in organizing the

exercise; we also present student feedback and draw conclusions and lessons learned on using cybersecurity

exercises as educational tools.

1 INTRODUCTION

Capture-the-flag (CTF) contents play a well-

established role in the cybersecurity culture, being at

once skill-testing grounds and community-building

platforms. A popular security learning website,

https://root-me.org(roo, 2021), has, at the time of

writing the article, more than 464 000 users, including

universities, security companies, commercial clients

and individual members. Other similar platforms host

tens of thousands of users, each providing hundreds

of challenges. While these contests provide education

benefits, their adaptation to academic objectives is

not straightforward, since the competitive nature of

CTFs makes them more appropriate for knowledge

evaluation than acquisition. Another issue resides in

the difference between learning and realistic chal-

lenges. While the industry is mostly biased towards

using realistic contests for training and recruiting,

students may be put off by the difficulty level, despite

their interest in hands-on experience.

A CTF contest consists in solving several security

challenges, usually in a timed manner, and providing

the organizers a proof-of-success (the flag). Another

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8287-1712

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3600-0531

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2351-4325

common scenario involves two teams, one of which

attacks the resources of the other, whose purpose is to

defend them. This is known as the red-team / blue-

team approach. Topics range from reverse engineer-

ing, digital forensics, cryptography and several types

of exploits. Design choices are multiple and also in-

fluence the difficulty of the contest and its suitability

for educational aims.

Our work relies on preparing, deploying and eval-

uating a cybersecurity exercise for university stu-

dents. The exercise was organized online by a con-

sortium of four universities. We followed three objec-

tives:

1. Stimulate students to enhance their cybersecurity

skills and pursue a career in cybersecurity. This

first objective addresses the gap between the hu-

man resources demands of the field and the num-

ber of students enrolling for university level secu-

rity tracks and masters programmes.

2. Evaluate the experience, knowledge and skills of

students in cybersecurity and how cybersecurity

contests (cyber-defence exercises, CTFs) help.

We aim to provide educators an integrative evalu-

ation on security topics, that targets multiple areas

of expertise and goes beyond curricula.

3. Collect feedback from participants and organiz-

ers to adapt future cybersecurity contents to max-

434

Deaconescu, R., B

˘

alt

,

oiu, A., Georgescu, T. and Puncioiu, A.

Using Cybersecurity Exercises as Essential Learning Tools in Universities.

DOI: 10.5220/0010994700003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 434-441

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

imize motivation and usefulness. Finally, driven

by the goal of creating a recurring event, we con-

struct a survey and analyze students’ feedback in

order to assess the impact of the contest.

The remainder of the paper is organized as fol-

lows. Section 1 reviews the state of the art in deploy-

ing CTFs for educational purposes, indicating tools,

best practices, lessons learned and challenges in us-

ing the competition format to address learning objec-

tives. Section 2 outlines the design choices in devel-

oping our cybersecurity exercise, from infrastructure

to game scenarios, while Section 3 reviews the re-

sults of the exercise. Finally, in Section 4, we present

the results of the survey we conducted in order to

understand participants’ drives, interests in the topic,

knowledge level and opinions on the challenge.

2 STATE OF THE ART ON

CYBERSECURITY EXERCISES

The growing interest in academic, commercial or

community-based CTF challenges has inspired the

creation of CTF platforms. A CTF platform or en-

gine is a software environment that allows the deploy-

ment of challenges, offering different implementa-

tion options and game scenarios. Article (

ˇ

Sv

´

abensk

´

y,

2021) gathers approximately 16,000 textual CTF so-

lutions which are used to study the distribution of

main cybersecurity topics. Investigated game con-

figuration options include possible “dependencies be-

tween challenges”, “number of accepted attempts”,

“time limit” and “re-submission options” (Kucek and

Leitner, 2020). In general, customizing the challenge

amounts to creating a configuration script that de-

fines the selected options (Taylor et al., 2017). De-

pending on the type of challenge, design options can

include limiting the number of submission attempts,

challenge availability (for example having a game re-

quire correct completion of another), hint availability

(with or without impact on scoring).

CTF modalities include online challenges, where

a system is either under attack and requires appro-

priate defensive measures to be taken by the contes-

tants or the other way around. In the offline type of

challenges, on the other hand, the system remains

unchanged throughout the challenge. The survey

in (Taylor et al., 2017) signals that most CTF chal-

lenges intended for educational purposes use either

of modalities, however they fail to integrate the two

types of approaches in a realistic scenario that would

be close to what a system’s administrator would en-

counter in practice.

The common opinion is that CTFs are, at large,

beneficial to the field of cybersecurity, which suf-

fers from lack of human resources and, according to

some authors, improper representation in graduate-

level curricula (Cheung et al., 2011).

Beyond the gamification setup employed by the

majority of the events, which in itself can be debatable

with respect to pedagogical benefits, CTFs clearly

imply several educational methods. Because of the

specifics of cybersecurity, it is often the case that sig-

nificant prior knowledge is needed on behalf of the

participants in order to ensure a competitive advan-

tage (Mansurov, 2016). Therefore, the event may not

constitute a learning environment per se, although this

aspect can be mitigated, as we present shortly. More-

over, some CTFs may put too much weight on the

competitive aspect (Taylor et al., 2017) or on mea-

suring know-how (Katsantonis et al., 2017) and leave

little room for encouraging learning. On the other

hand, challenge-based learning, which is also inher-

ent to these events, implies more focus on the student

and opens the field to problem-based learning. For a

more detailed review on the pedagogical theory asso-

ciated with CTF challenges, see (Katsantonis et al.,

2017) and (Mansurov, 2016).

A more nuanced opinion is that the competitions

alone, although driving interest to the field, may have

limited pedagogical advantages, however significant

benefits can be drawn if CTFs are used as pretext for

organized extracurricular study groups.

University of Altai State University, Russia, orga-

nized a CTF-like learning environment, in the form of

an extracurricular club that used university resources

(infrastructure, staff) to support students competing in

CTF challenges (Mansurov, 2016). Steady growth of

membership was observed in the course of three years

after the club was established. More than 80% of

students evaluated that attending club workshops and

competitions resulted in the acquisition of new skills,

knowledge and hands-on experience, while 60% said

that it was also useful in studying for their regular

courses.

The high technical skills required in some compe-

titions seems to be by far the most perceived draw-

back of CTFs, especially by new participants (Kat-

santonis et al., 2017), (Chung and Cohen, 2014). An-

other important aspect indicated by participants con-

cerns the feedback received. While ranking in itself

gives an overall idea on how well each participant

did in the challenge, students require a more person-

alized evaluation of their work (Chung and Cohen,

2014), (Chothia and Novakovic, 2015).

Studies in (Katsantonis et al., 2017), (Chung and

Cohen, 2014) and (Chothia and Novakovic, 2015)

Using Cybersecurity Exercises as Essential Learning Tools in Universities

435

also reference participant feedback on organizational

aspects of CTFs, such as diversity in topics, chal-

lenge design choices, types of technical constraints,

frequency of events.

3 PRACTICAL WORK

Aiming to evaluate the education benefits of cyber-

security exercises, we conducted an online practical

security contest as a proof-of-concept event. We used

a VM-based infrastructure to construct a vulnerable

configuration that participants were tasked with pro-

tecting. In the end, participants were required to fill

a security report detailing their findings and actions

undertaken.

We used the proof-of-concept security exercise

for multiple goals. Firstly, we aimed to test the

VM-based infrastructure for functionality and ease of

use. Secondly, we looked at validating scenario ideas,

evaluating their suitability for the exercise and get-

ting participants’ reaction. Thirdly, we aimed to col-

lect feedback from participants to improve the envi-

ronment, setup and quality of scenarios.

3.1 Infrastructure and Environment

The infrastructure consisted of a pod of four virtual

machines connected together in a shared network.

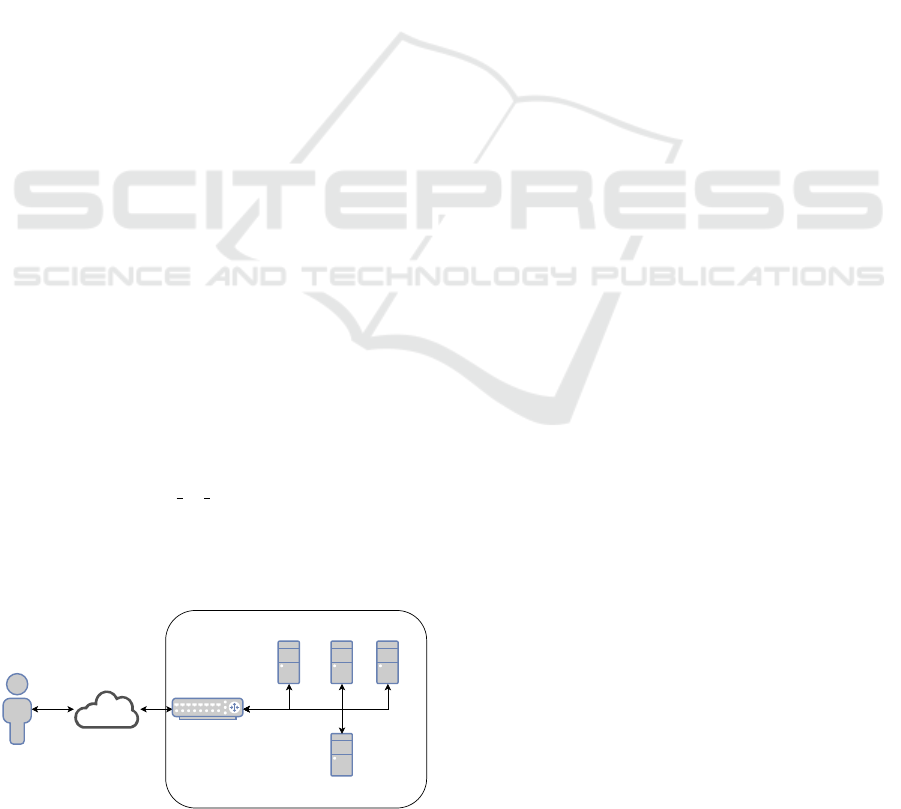

Figure 1 presents the infrastructure of a pod. One vir-

tual machine was used by organizers as an “attacker”

station. The other three virtual machines were pro-

vided to participants. Each of these virtual machines

was configured with different vulnerabilities to be in-

vestigated and fixed by each team. One virtual ma-

chine was running Windows, the other two were run-

ning Linux.

Teams were given access to their own pod. There

was a pod for each team, with the number of VMs

totalling 4 x number

of teams.

Virtual machines were located in a private infras-

tructure, with access being provided via a VPN con-

nection. Each team was provided access to their own

pod, with no access to the other pods.

POD

linux2 vm windows vmlinux1 vm

"attacker" VM

Figure 1: Infrastructure of a Virtual Machine Pod.

Virtual machines could be configured offline or

online. Once the configuration is done, the seed vir-

tual machine is duplicated to all virtual machines in

the pods. As part of our exercise, the Windows vir-

tual machine was configured offline whereas the two

Linux virtual machines were configured online.

Once the infrastructure was prepared (virtual ma-

chine pods, networking, VPN access) team accounts

were configured for each team. Each team was able to

login to a managing infrastructure and get the config-

uration details for the VPN and access to each pod.

Only the Windows and the Linux virtual machines

were made available to the team. The attacker vir-

tual machine is used by the organizers and the team

should not aim to access or attack it.

For participant interaction we deployed a Discord

server that we configured for both internal use in the

team and discussions with participants. Dedicated

channels were created for each team for use during

the exercise.

3.2 Contest Specifics

As a proof-of-concept exercise, we selected 8 teams

of students from 4 partner universities. Each partner

university provided two teams of 2-4 students.

The proof-of-concept exercise took 8 hours, with

teams tasked with identifying, fixing and document-

ing security-related issues in the 3 virtual machines of

their pod (a Windows virtual machine and two Linux

virtual machines). For the Linux virtual machines a

scoring infrastructure validated the presence (or ab-

sence) of flaws. This infrastructure used a series of

scripts from the attacker station as part of the pod to

remotely query the target Linux virtual machines and

report the status to a scoring station. Queries were

sent out every minute and participants could check the

scoring station for an update on their progress.

Feedback was collected from participants, the re-

sults of which are part of Section 4. Each team created

a report of their findings, submitted to the organizers

via Discord.

3.2.1 Windows Challenge Design

Challenges for Windows virtual machines were de-

signed with a system compromise scenario in mind,

with the aim of quickly identifying an incident and

thus extracting indicators of compromise, collecting

left behind malware, as well as identifying existing

vulnerabilities in the system which may lead to the

system exploitation.

Participants were required to collect evidence, de-

sign and apply security fixes and document findings

and fixes as part of a technical report. The report

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

436

should have been created based on a list of guiding

questions:

• Infection Vectors Exploited by the Attacker to

Compromise the System: There was used a phish-

ing campaign targeting the user’s endpoint as well

as a trojanized chrome extension which was rec-

ommended to the user.

• Persistence Mechanisms and Lateral Movement

Techniques Used by the Attacker: There were

WMI and schedule task techniques used to estab-

lish persistence at the system’s level, and multi-

ple PowerShell scripts leveraged for lateral move-

ment.

• Artifacts Left behind at the System Level: There

were multiple artefacts that would imply ad-

vanced investigation, surface analysis, script de-

obfuscation and / or malware analysis in a form

of .exe, .py, .ps1, .apx, .pl, and .vbs files.

• Possible Tactics and Techniques Leveraged to

Compromise Existing Industrial Control Equip-

ment: as part of a the simulated ICS lab, proto-

cols used, possible malicious elements, type of

systems concerned.

3.2.2 Linux Challenge Design

Challenges for Linux virtual machines were designed

as online challenges, directly on a seed virtual ma-

chine. Linux challenges were designed, reviewed and

stored as part of a repository, together with deploy-

ment and validation scripts. Deployment scripts were

used to install Linux challenges (i.e. pre-configured

flaws) on the seed virtual machine, while validation

scripts were deployed and used on the attacker virtual

machine to retrieve status of flaws and update scoring.

The system was assumed to be hacked, resulting

in multiple issues left behind by the attacker. More-

over, other issues were present due to assumed poor

administrative decisions. Both the malicious flaws

and non-intentional misconfiguration had to be dis-

covered and fixed by participants in order to get con-

test points.

There were 10 Linux challenges, described below:

1. command: A web server is using an unverified in-

put vulnerability to execute shell commands.

2. expired: There is an expired certificate on a web

server. This needs fixing.

3. admin1: The MySQL database server is accessi-

ble via admin / admin. This is an administrative

password allowing access to the entire database.

4. admin2: A web server path is configured to use

admin / admin.

5. admin3: The LDAP service is accessible via

admin / admin. This is an administrative pass-

word allowing access to the entire database.

6. really: The MTA configured on the system is

open-relay allowing spam messages to be deliv-

ered by the system, irrespective of their source.

7. shadow: A given executable (/usr/bin/rev) is

configured via Linux capabilities to read all files

in the system, this includes /etc/shadow.

8. sign: A digital signing service has a buffer over-

flow vulnerability. The netstat executable has

been replaced to “hide” the presence of the dig-

ital service.

9. super: A local user (fred) can access the root

account via sudo.

10. todo: There is a NodeJS + mongodb web app

where users can add items.

Each challenge was deployed on one of the two

Linux virtual machines. Validation scripts were de-

ployed on attacker machines.

4 RESULTS

In this section we present the results of the proof-of-

concept exercise we designed and deployed. As pre-

sented above, there were eight teams part of the con-

test solving challenges on Windows and Linux virtual

machines for 8 hours.

At the end of the contest, we asked participants

to fill a survey and draft reports of their work. The

analysis of the survey is discussed in Section 4. In

this section we present contest results and an analysis

of the reports.

10 challenges were deployed on Linux VMs. One

challenge (command) was solved by all teams, while

one challenge (sign) wasn’t solved by any team. Ta-

ble 1 shows a summary of the Linux results.

The Windows challenges were identified and re-

solved by the majority of the teams with everyone

providing comprehensive technical reports detailing

the windows specific challenges but with the ICS re-

lated portion mostly untouched, even if ICS artefacts

got extracted. During the contest, Discord was used

for inner-team discussions and discussions between

team members and the organizers. A general chan-

nel available to all teams was used for announce-

ments and public discussions. A private channel was

available to each team. Each channel consisted of a

text sub-channel and a voice/video sub-channel. The

number of messages on each channel varied accord-

ing to the team as shown in Table 2.

Using Cybersecurity Exercises as Essential Learning Tools in Universities

437

Table 1: Linux Challenge Results.

Team command expired admin1 admin2 admin3 really shadow sign super todo

Team1 x

Team2 x x x

Team3 x x x x

Team4 x x x x

Team5 x x x x x x

Team6 x x x x

Team7 x x x x x x

Team8 x x

Table 2: Number of Discord Messages.

channel number of messages

General 194

Team1 7

Team2 3

Team3 64

Team4 35

Team5 21

Team6 30

Team7 44

Team8 6

Most discussions between organizers and teams

happened inside the “General” discussion chan-

nel. Team interaction mostly happened inside the

voice/video channels, and only partially on the text

channel; team text channels were mostly used for pri-

vate interaction with the organizers.

For most of the time during the contest, there were

no issues with the infrastructure. At certain points,

participants had misconfigured their SSH connection

or accidentally shut down their virtual machines, re-

quiring support from the organizers. A particular is-

sue had to do with running the Wireshark graphical

application via SSH. Because of a package configu-

ration issue on the Linux virtual machines, it failed.

Once the solution was provided (the package had to

be reconfigured), participants could use Wireshark as

a graphical application on the remote system.

4.1 Summary of Reports

As a direct benefit of the exercise, summarized by par-

ticipants, its practicality is an important part. Partici-

pants were able to work on practical realistic scenar-

ios. Another benefit is the use of validation value: be-

ing able to test one’s cybersecurity skills and knowl-

edge.

One of the main downsides, as signaled by par-

ticipants, was detecting actual issues and separating

them from expected or harmless behavior. With the

issue discovered, the expected solution itself was un-

clear as certain solutions would not be validated by

the automated checking infrastructure.

Another downside was the broad spectrum of

challenges, ranging from misconfigurations to pass-

word management to faulty services. As previous

experience was mostly gained in CTF contests with

standard challenges, it was difficult for participants to

detect the issue. It was expected that the issue would

be obvious and most of the effort would be spent on

fixing it, rather than the other way around.

We drew several suggestions from live discussions

with participants and their reports:

• Add solution validation from the very beginning

and make it deterministic, such that participants

will know they solved it.

• Make the validation more realistic and straightfor-

ward. Certain checkers required a level of access

to the remote system in order to validate the so-

lution. And one could confuse that access as a

possible break in attempt.

• Provide participants with documentation on the

types of challenges employed, such as pointing

them to realistic vulnerability boxes such as Hack-

TheBox.

• Provide a clear narrative of the exercise, such that

participants will have a clear overall view of the

setup.

• Add pointers on how to approach the challenges,

especially on Windows virtual machines where

participants have less experience.

5 ANALYSIS OF PARTICIPANT

FEEDBACK

We designed and deployed a survey to gather feed-

back from participants. This was aimed to help im-

prove future CTF events, on one hand, and to study

the characteristics of people interested in cybersecu-

rity exercises, on the other. Before developing the

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

438

questionnaire, a research on similar work was per-

formed. Article (Karagiannis and Magkos, 2020)

discusses the potential of CTF challenges to engage

in cybersecurity learning for undergraduate students.

Paper (Leune and Jr., 2017) studies the educational

effects of CTF towards students, by using a survey

before and after participating in the CTF.

5.1 Survey Methodology

We collected data from 26 participants. The survey

was anonymous and was structured in three main di-

rections: (1) information regarding the CTF contest,

(2) data regarding participants’ cybersecurity back-

ground and (3) questions that may indicate the partic-

ipants’ level of general knowledge regarding cyberse-

curity. The main results are presented below and the

full list of questions can be consulted in Annex 1.

We defined several hypotheses:

1. Hypothesis 1: The contesters with better grades

in university get better results in the CTF events.

The participants are usually computer science for-

mer students or employees in domains connected

to IT. Since cybersecurity is often a secondary dis-

cipline in faculties focused on computer science,

we looked at the correlation between a student’s

general IT knowledge and CTFs results.

2. Hypothesis 2: The contesters with certifications

score better than students with few or no certifi-

cations. Nowadays, certifications are considered

important inside organizations and they can offer

an advantage for employment or promotion. We

wanted to check how much the certifications con-

nected with cybersecurity help the participants to

have better results in the CTF.

3. Hypothesis 3: Generally, the participants have

the ability to properly evaluate themselves. We

asked the participants to auto-evaluate their level

of training in both IT and cybersecurity. We cor-

related their answers with the scores they obtained

in the CTF.

5.2 Information about the Contest

Most of the participants were motivated by their will

to improve knowledge and skills, 46% were mainly

focused on cybersecurity while 19% wanted to gather

general computer science knowledge. An important

part of the participants were driven by curiosity (27%)

and approx. 8% by entertainment. The degree of diffi-

culty was somewhere between average and increased

and the allocated time for the event was considered

appropriate by the most, however 27% of participants

considered that they needed more time.

Over 73% of the contesters considered the quality

of the received indications average or better. 88.5% of

the contesters evaluated the instruments they had ac-

cess to at least acceptable, while 58% were very sat-

isfied. An important aspect that can be improved can

be considered the dissatisfaction of some of the par-

ticipants towards the task structure, since only 61.5%

of them were pleased, while 23% were pleased to a

small extent and 15.5 were unhappy. We hypothesize

the cause of this is connected to our effort to create

scenarios as close as possible to those in practice. As

such, the CTF structure was slightly different than in

most of the similar events.

5.3 Information about Participant

Experience

The vast majority of participants were university

graduates (81%), while another 11.5% were in the

graduation phase. 85% of students graduated with

80% or more and 35% with 90% or better. Most

of the students had been active in the IT work field

(92.3%), however 57.7% of them had very little expe-

rience (0-2 years). 69% of them had work experience

in a position that included cybersecurity tasks, while

38.4% have achieved at least one cybersecurity cer-

tificate. Moreover, 84,6% had participated in CTFs or

similar events in the past.

Figure 2 shows the level at which participants self-

evaluate themselves in both cybersecurity as well as

IT in general. As can be observed, they rather consid-

ered themselves better trained in IT, with a weighted

average score of 89 than in cybersecurity, with a

weighted average score of 65 out of the maximum

possible of 130.

Figure 3 shows the contesters score ranges. It is

worth mentioning that we couldn’t ask the partici-

pants for their exact score in order to keep the sur-

vey anonymous. Out of the total 26 contesters, 15

obtained a score between 20% to 40%, eight of them

gained between 40% and 60%, two achieved scores in

60%-80% range and one participant solved correctly

more than 80% of the tasks. There is a high interest

among the participants in the field of cybersecurity,

since more than 2/3 are using cybersecurity special-

ized publications to study up to date information at

least once a week.

Besides software, the contesters were generally

better prepared in operating systems, data structures

and computer networking than in mathematics and

hardware, as shown in Figure 4.

Using Cybersecurity Exercises as Essential Learning Tools in Universities

439

Figure 2: Self Evaluation.

Figure 3: Score Distribution.

Figure 4: Auto-evaluation for Disciplines.

5.4 Participant Profile

Based on the survey, we made a participant pro-

file which may be helpful because (1) we can eas-

ily identify which students may be interested to par-

ticipate in CTFs and which may not and (2) we can

easily identify which students may be interested in

the cybersecurity field. Although most of the stu-

dents are rather prepared in computer science in gen-

eral than in cybersecurity in particular, 70% are se-

riously interested in the field of cybersecurity. They

are usually well-prepared students, 85% having av-

erage grades over 8 and one third over 9 (out of

10). Most of the participants seemed to have good

team working skills, since over 88% of them were

pleased with their team cohesion. One third of the

contesters have certifications and 85% have partici-

pated in similar events such as CTFs before. They are

rather better prepared in Operating systems, network-

ing, and data structures than in hardware. Most of

them have solid programming knowledge, especially

in languages C/C++, Python, Java, C#, JavaScript and

PHP. Also, over 50% are familiar with assembly. Re-

garding cybersecurity knowledge, they tend to be bet-

ter theoretical prepared than practical, since they are

more familiar with concepts that can be understood

by studying theoretically, but rather less familiar with

concepts that require more practice.

5.5 Testing the Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1. The contesters with better grades in

university gets better results in the CTF event.

As can be observed in Table 3, the higher the par-

ticipants’ grades, the better the results obtained in

CTF, thus our hypothesis is valid.

Table 3: Level of Study vs Results.

Score/Grade 5-6 7-8 8-9 9-10 Total

0-20%

20,01-40% 1 1 11 2 15

40.01-60% 1 2 4 7

60.01-80% 2 2

80,01-100% 1 1

Total 1 2 13 9 25

Hypothesis 2. The contesters with more certifica-

tions score better than students with less or without at

all.

There is no evidence that the number of cyberse-

curity certifications or other certifications connected

to it helped the contesters in getting better results, in

Table 4.

Table 4: Contestant scores grouped by number of certifica-

tions.

Score/Certs 0 1 2-3 >3 Total

0-20%

20,01-40% 11 2 1 1 15

40.01-60% 3 4 1 8

60.01-80% 2 2

80,01-100% 1 1

Total 16 6 1 3 26

Hypothesis 3. Generally, the participants have the

ability to properly evaluate themselves.

Table 5 shows that generally students properly

evaluated themselves.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

440

Table 5: Contestant results vs Auto-evaluation.

Score/Level 1 2 3 4 5 Total

0-20%

20,01-40% 4 1 8 2 15

40.01-60% 1 5 1 1 8

60.01-80% 2 2

80,01-100% 1 1

Total 4 4 13 3 2 26

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

Cybersecurity is substantially growing worldwide,

preparing new specialists for an increasing number

and diversity of jobs. Universities must play an im-

portant role in attracting students towards cybersecu-

rity and training them to become specialists.

In this paper we presented our take in organizing

a cybersecurity exercise targeted towards university

students. The main objective was to stimulate stu-

dents to enhance their cybersecurity skills and pursue

a career in cybersecurity. Using this opportunity, we

also evaluated students’ experience, knowledge and

skills. We also collected valuable feedback from par-

ticipants to use in future events.

In order to develop a good quality exercise, first

we studied the state-of-the-art of these types of events.

Based on our study, we developed a proof-of-concept

cybersecurity exercise. The exercise was designed to

stimulate students to pursue a career in cybersecurity

and allow an assessment of their skills. We aimed to

focus on more realistic scenarios.

We conducted a survey to evaluate students’ ex-

perience in the contest. Compared to other CTF

(capture-the-flag) contests, our contest was consid-

ered more practical than other similar events they took

part in. A positive aspect is the diversity of chal-

lenges. On the negative side, students considered the

CTF scenarios a bit too broad considering their expe-

rience.

Based on their results and collected feedback, we

obtained a general participant profile. This can be

very useful in order to identify future students that

may be interested to pursue a career in cybersecurity.

Also, we formulated three hypotheses, two of which

proved to be valid, while one is inconclusive.

Based on the results and findings, we will work on

our project in several ways. We will improve contest

challenges based on the collected feedback. In order

to collect more information, we will scale future exer-

cises to more participants. For advertising future con-

tents, we will use the general profile to attract

students that are suited for a career in cybersecurity.

REFERENCES

(2021). root-me. Last accessed: September 28, 2021.

Cheung, S., Cohen, P., Lo, Z., and Elia, F. (2011). Chal-

lenge based learning in cybersecurity education. In

Proceedings of the International Conference on Secu-

rity and Management.

Chothia, T. and Novakovic, C. (2015). An offline capture

the flag-style virtual machine and an assessment of its

value for cybersecurity education. In 2015 USENIX

Summit on Gaming, Games, and Gamification in Se-

curity Education (3GSE 15).

Chung, K. and Cohen, J. (2014). Learning obstacles in the

capture the flag model. In USENIX Summit on Gam-

ing, Games, and Gamification in Security Education

(3GSE 14). USENIX Association, San Diego, CA.

Karagiannis, S. and Magkos, E. (2020). Adapting ctf

challenges into virtual cybersecurity learning environ-

ments. Information & Computer Security.

Katsantonis, M., Fouliras, P., and Mavridis, I. (2017). Con-

ceptual analysis of cyber security education based on

live competitions. In IEEE Global Engineering Edu-

cation Conference (EDUCON), pages 771–779.

Kucek, S. and Leitner, M. (2020). An empirical survey of

functions and configurations of open-source capture

the flag (ctf) environments. Journal of Network and

Computer Applications, 151.

Leune, K. and Jr., S. J. P. (2017). Using capture-the-flag to

enhance the effectiveness of cybersecurity education.

In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Conference on In-

formation Technology Education.

Mansurov, A. (2016). A ctf-based approach in informa-

tion security education: An extracurricular activity in

teaching students at altai state university, russia. Mod-

ern Applied Science.

Taylor, C., Arias, P., Klopchic, J., Matarazzo, C., and Dube,

E. (2017). Ctf: State-of-the-art and building the next

generation. In USENIX Security Symposium.

ˇ

Sv

´

abensk

´

y, V. (2021). Cybersecurity knowledge and skills

taught in capture the flag challenges. Computers &

Security 102, 102154.

Using Cybersecurity Exercises as Essential Learning Tools in Universities

441