Determinants of International Remittances in Mexico:

Economic vs. Financial Variables

Miguel Cruz Vasquez

1a

and Fernando Vera Sánchez

2b

1

Facultad de Economía, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, 17 Sur 901, Puebla, Mexico

2

Escuela de Economía y Negocios, Universidad Anáhuac de Puebla, Avenida Orion Norte S/No., Tlaxcalancingo, Mexico

Keywords: Remittances, Economic Variables, Financial Variables, VAR, DAG.

Abstract: This work seeks to analyze whether economic or financial variables are more important in determining the

remittances sent by Mexican migrants in the United States to their communities of origin. For this, we estimate

three models: a linear regression model with all the variables transformed to first differences, to eliminate the

possibility of spurious regression; an autoregressive vector (VAR) model that approximates the relationships

between variables in the absence of consolidated theories; and Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) model, which

is the most appropriate for estimating causal relationships between variables. The results show that the most

important variables in determining the remittances of Mexican migrants in the United States are the economic

ones, specifically, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the United States and the Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) of Mexico.

1 INTRODUCTION

Remittances are one of the main results of the

migration process and constitute an important source

of income for millions of Mexican families, as well

as an important source of foreign exchange for

Mexico.

Remittances sent by Mexican migrants in the

United States have shown a growing evolution since

their emergence, particularly in the period analyzed

in this paper, between the first quarter of 1995 and the

second quarter of 2021. In nominal figures, the

remittances received during 2020 were 652% higher

than in 1995, 397% higher than in 2000, 83% higher

than in 2010, and 11% higher than in 2019. For the

years 1995, 2000, 2010, 2019, and 2020, remittances

amounted 5,667, 8,572, 23,313, 38,457 and 42,624

million dollars (Banxico, 2021). This growing trend

has been exposed in different dissertations (Canales,

2006; Islas and Moreno, 2011; Valdivia, et al., 2020).

Regarding the theories that explain the sending of

remittances from host countries to migrants' home

countries, the theoretical and empirical literature

indicate two groups of determinants; the first is

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1662-2579

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3501-6478

grouped within the Endogenous Migration approach,

which considers the sending of remittances as an

endogenous variable within the migration decision

process, together with the length of stay, savings, and

others, in addition to assessing family relationships

and aspects like the socio-economic situation of

migrants. All of them consider altruism as a central

source that explains the sending of remittances; while

the second is grouped within the Portfolio

Optimization approach, which considers that only the

self-interest of migrants motivates sending money.

Additionally, this decision is independent of their

decision to migrate and the conditions of their family

(Islas y Moreno, 2011).

The first is clearly dominated by economic

determinants while financial variables prevail in the

second, there is no consensus in the literature about the

predominance of one approach over the other. The

objective of this essay is to contribute to the debate on

the importance of economic and financial determinants

in determining the remittances sent by Mexican

migrants to their communities of origin from the

United States. We also intend to contribute to the study

of public policies of an economic and financial nature

to encourage the entry of remittances into Mexico.

Vasquez, M. and Sánchez, F.

Determinants of International Remittances in Mexico: Economic vs. Financial Variables.

DOI: 10.5220/0011034700003206

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2022), pages 35-42

ISBN: 978-989-758-567-8; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

35

This work consists of an introduction, theoretical

and empirical antecedents, methodology, results and

discussion, and, finally, conclusions.

2 THEORETICAL AND

EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND

There are two main (not necessarily irreconcilable)

approaches to modelling remittances from

international workers. The first treats international

remittances as an endogenous variable in the

decision-making process on migration and

remittances within the family, while the second treats

them as savings transfers from one region to another.

In the first, the determinants of international

remittances are dominated by family relationships,

while in the second, investment portfolio

considerations are emphasized (Elbadawi and Rocha,

1992; Islas and Moreno, 2011).

2.1 The Endogenous Migration

Approach to International

Remittances

In this approach, the ability to remit is directly

associated with the salary received in the host country

and the saving behaviour of the migrant, both of

which suggest a decision process in which the level

of savings is determined along with the participation

to be remitted to the home country (Elbadawi and

Rocha, 1992).

In this model, the migrant is seen as the traditional

macroeconomic-maximizing agent of the

intertemporal utility function that generates a saving-

consumption route, both in the country of origin and

in the host country; although in them the migrant

savings program is more complex than the standard

savings program since they need to know information

on relative prices abroad, wage routes and interest

rates, as well as the duration of their stay abroad.

Djajic (1989) uses this structure to generate the

optimal overseas savings rate and leisure and

merchandise consumption routes in the context of

guest-worker migration

1

.

An alternative version of this approach treats

remittances as an intertemporal contractual

agreement between the migrant and his family, in

which the family contract is considered as a risk-

1

The analysis of (Djajic, 1989) is based on the

determination of the pattern of leisure and consumption

of goods both in the host country and in the country of

origin and its comparison with the patterns of leisure and

sharing agreement between the family and the

migrant. That agreement compensates for the

prevailing lack of insurance markets in developing

countries, especially in rural areas. The benefit for the

migrant is guaranteed income during cyclical

downturns, while the benefit for the family is a better

risk-return frontier so that they can assume riskier

investments, such as the mechanization of the

countryside (Elbadawi and Rocha, 1992).

2.2 Portfolio Approach to International

Remittances

In this approach, remittances are the result of a

broader portfolio allocation process by the migrant

worker, a process by which the migrant must decide

whether to keep their savings in the host country or

send them to their country of origin in the form of

either real or financial assets. This perspective,

therefore, bases the migrant worker’s decision to

remit on relative rates of return, relative prices, and

uncertainty as basic determinants (Elbadawi and

Rocha, 1992).

Under this approach, Swamy (1981) includes as

determinants of international remittances the

following variables: the differential in the interest

rates of the country of origin relative to the interest

rate of the host country, the difference in the rates of

return on real estate in the home country with respect

to the similar rate in the host country, the real

exchange rate in the country of origin, the stock of

migrants and their earnings in the host country.

On their part, Glytsos and Katseli (1986) generate

a budgetary restriction for migrants, where the return

on the portfolio is a function of their wealth, foreign

and domestic interest rates, and the variability of the

exchange rate. For them, the budget constraint and the

risk-return preferences program jointly determine the

part of the migrant's portfolio that will be placed in

assets in the country of origin.

2.3 Empirical Background

Among the empirical studies on the determinants of

remittances in Mexico, Castillo (2001), who

emphasizes the scarcity of studies on the determinants

of remittances to Mexico despite its importance as a

fundamental income for a large number of families in

Mexico, performs a cointegration analysis that

establishes a long-term positive relationship between

consumption of goods chosen by the natives of the host

country on the one hand and non-migrants in the country

of origin on the other.

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

36

remittances and the United States GDP, as well as a

long-term negative relationship between remittances

and Mexico's GDP and between remittances and the

real exchange rate.

Another study from our country is the one

presented by Salas and Pérez (2006), it analyzes the

influence of macroeconomic variables on the sending

of remittances from the United States to Mexico and

the effect that these have on the distribution of income

in Mexico. To do this, they use a short-term

econometric model that relates remittances to

Mexican monetary policy variables (inflation,

interbank interest rate, and exchange rate) as well as

economic variables (foreign direct investment,

Mexican GDP, and United States GDP). They find

that Mexico's GDP and inflation inversely affect

remittances sent to the country, while the United

States' GDP affects them directly.

Another study, Islas and Moreno (2011), analyzes

the macroeconomic variables that determine the flow

of family remittances from the United States to

Mexico. To do this, it carries out an econometric

exercise using Vectors Autoregressive with Error

Correction (VAR) to identify, from a synthetic

perspective, the long-term determinants of family

remittances that arrive in Mexico. Their results show

that remittances are the consequence of an investment

decision rather than altruism on the part of migrants

since the impact of interest rates is clearer than the

impact of Gross Domestic Product.

For the case of other countries, Suamy (1981)

gathers available data on the remittances of workers

from Turkey, Yugoslavia, and Greece and analyzes

the regional structure and the growth of these flows;

he relates the flow of remittances to the level and

fluctuations of economic activity and to inflation in

the recipient countries. The results of the analysis

show that these last variables, as well as the number

of migrants and their wages, significantly affect a

large part of the variation in remittance flows; while

the relative rates of return on saving both in the host

country and in the home country and the incentive

schemes in the country of origin, such as the foreign

currency deposit scheme and the exchange rate

premium, do not seem to have a significant impact on

total remittances.

There is also the work of Elbadawi and Rocha

(1992), which proposes an empirical model for the

determination of remittances, which includes

demographic, macroeconomic, and portfolio factors as

well as special incentive policies. They use data from

5 labour-exporting countries in North Africa and

Europe: Morocco, Portugal, Tunisia, Turkey, and the

former Yugoslavia. Their results show that remittances

are significantly affected by the economic policies of

their country of origin (labour exporting countries) and

that special incentive schemes to attract international

remittances cannot substitute a stable and credible

macroeconomic policy.

The study by El-Sakka and McNabb (1999)

considers the macroeconomic determinants of

remittances from migrants to their home countries. In

the case of Egypt, they find, in contrast to other

studies, that both the real exchange rate and the

differential in interest rates are important for

attracting remittances through official channels.

On one hand, Tuncan, Neyapti, and Metin-Ozca

(2005) point out that the flows of workers'

remittances in Turkey have increased since the 1960s,

and they continue to be a significant proportion of

imports. They presented empirical evidence that the

premium of the black market, interest rate

differential, inflation rate, economic growth, income

from both home and host countries, and periods of

military rule have significantly affected remittance

flows to Turkey. Among them, the negatively

significant effects of the black-market premium,

inflation, and the military regime dummy indicate the

importance of sound exchange rate policies and

economic and political stability for attracting

remittance flows; likewise, there are reasons for both

consumption and investment smoothing, although the

latter seems more prevalent after the 1980s.

On the other hand, the article by Rapoport and

Docquier (2005) reviews the recent theoretical and

empirical economic literature on migrant remittances

in a microeconomic section on the determinants of

remittances and a macroeconomic section on their

effects on growth. At the micro level, they present in

a completely harmonized framework the various

motivations to refer described in the literature. The

results of empirical studies show that a mixture of

individualistic and family motives explains the

probability and size of remittances. At the macro

level, they briefly review the standard (Keynesian)

literature and trade theory on the short-term impact of

remittances. They then use an endogenous growth

framework to describe the growth potential of

remittances and present the evidence for different

growth channels.

Also, Vargas-Silva and Huang (2005) examine

the determinants of workers' remittances. They use

variance decompositions, impulse response

functions, and Granger causality tests derived from an

error correction vector, to test whether remittances

are affected by macroeconomic conditions in the host

country (sending remittances) or the home country

(remittance recipient). The data used correspond to

Determinants of International Remittances in Mexico: Economic vs. Financial Variables

37

Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, El

Salvador, Mexico, and the United States. The results

indicate that remittances respond more to changes in

the macroeconomic conditions of the host country

than to changes in the macroeconomic conditions of

the home country.

3 METHODOLOGY

To explain remittances from Mexican migrants in the

United States to Mexican communities, in the present

work we estimate the relationship between

remittances (𝑅𝐸𝑀

) and endogenous and portfolio

migration factors, in coincidence with the models

proposed by Islas and Moreno (2011) and El-Sakka

and Mc Nabb (1999), as follows:

𝑅𝐸𝑀

=𝑓 (𝐺𝐷𝑃

,𝐺𝐷𝑃

,𝐼

,𝐼

,𝐸

,𝐼𝑁𝐹𝐿𝐴

)

(1)

where 𝐺𝐷𝑃_𝑈𝑆𝐴 is the Gross Domestic Product

of the United States, 𝐺𝐷𝑃_𝑀𝑋 is the Gross Domestic

Product of Mexico, 𝐼_𝑈𝑆𝐴 is the US interest rate,

𝐼_𝑀𝑋 is the interest rate of Mexico, 𝐸 is the real

exchange rate Mexico-United States, 𝐼𝑁𝐹𝐿𝐴 is the

inflation rate in Mexico. As it can be seen, the first

two variables are economic, while the remaining four

are financial.

According to the Endogenous Migration theory, a

positive relationship between remittances would be

expected with the variable 𝐺𝐷𝑃_𝑈𝑆𝐴, since as the

economy of the United States (the host country)

grows, remittances to Mexico will grow; while a

negative relationship of remittances with the variable

𝐺𝐷𝑃_𝑀𝑋 would be expected, since as the economy

of Mexico (the home country) grows, the economic

situation in it would improve and thus remittances to

Mexico would be reduced.

On the other hand, according to the Portfolio

theory, a positive relationship between remittances

would be expected with any of the variables with the

highest value, 𝐼_𝑈𝑆𝐴 o 𝐼_𝑀𝑋. This would indicate that

the migrant would invest their savings either in the host

country or by sending it as remittances to the country

of origin, depending on whether the interest rate is

higher in the United States or Mexico. We would also

expect a positive relationship of remittances with the

variable E, since an increase in the real exchange rate

of Mexico, that is, a depreciation of it, would lead to an

increase in remittances, due to the increase in Mexican

currency that the migrant would receive for each dollar.

Likewise, we would expect a negative relationship of

remittances with the variable 𝐼𝑁𝐹𝐿𝐴, since the

increase in inflation in the home country, Mexico,

would lead to an increase in remittances, due to the loss

of the purchasing power of money in the home country.

The data used in this work correspond to the

period between the first quarter of 1995 and the

second quarter of 2021. The remittance figures were

obtained from quarterly data on remittances sent by

Mexican migrants in the United States reported by

Banco de México in millions of dollars from 1984.

The figures of the Gross Domestic Product of the

United States were procured from the database of the

Bureau of Economic Analysis in billions of dollars of

the year 2012. The figures for the Gross Domestic

Product of Mexico were collected from INEGI in

millions of pesos at 2013 prices. The United States

interest rate was attained from the nominal interest

rate of government instruments at one month in that

country, reported by the Department of the Treasury

of the United States. The Mexican interest rate was

recovered from the 28-day nominal interest rate of

Cetes, reported by Banco de México. The figures for

the real exchange rate were obtained from the series

of the Banco de México's Economic Information

System of the nominal exchange rate converted to the

real exchange rate based on 1984. The figures for the

inflation rate for Mexico were also acquired from the

database of the annual underlying inflation rate of

Mexico reported by Banco de México.

Table 1 shows the quarterly descriptive statistics

of the variables used in this work, which shows the

contrasting values between the variables of the

migrant's home country (GDP_MX, I_MX, E and

INFLA) and those of the host country of the migrants

(GDP_USA and I_USA).

Table 1: Quarterly descriptive statistics of the variables,

period 1995: Q1 - 2021: Q2.

Variable Mean Std. Dev.. Units

REM 5,016.48 2,770.46 Mill.

dll.

GDP_MX 14,706,695.49 2,442,205.06 Mill.

Pesos

2013

I

_

MX 10.75 10.66 %

E 67.26 21.68 Pesos/

dll.

1984

INFLA 7.94 9.37 %

GDP_USA 15,200.23 2,415.97 Bill.

dll.

2012

I_USA 2.36 2.25 %

Source: Indicated in the text.

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

38

The main objective of this work is to test whether

financial or economic variables are the most

important in determining remittances sent by

Mexican migrants who are in the United States.

To do this, we estimate three models: a) a

regression model considering remittances as the

dependent variable, but transforming all variables into

first differences due to the time-series nature of the

variables, in which all variables were subjected to the

Augmented Dickey-Fuller stationarity test, which aims

to avoid the possibility of spurious regression; b) a

Vector Autoregressive model that approximates the

relationships between variables in the absence of

consolidated theories; and c) a Directed Acyclic Graph

model, which is considered the most appropriate to

estimate causal relationships between variables.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Regression Model

As we mentioned earlier, all the variables of the

regression model are estimated in first differences,

the results of which show, as can be seen in table 2,

that the main variables to explain remittances are the

US GDP, the Mexican GDP, and the real exchange

rate Mexico-United States, if we consider the p-value

less than 0.05 as the level of significance.

Table 2: OLS regression with variables converted into first

differences.

Variable Coefficient p-value

C -1.183056 0.3127

(1.16584)

GDP_USA1 -0.022008*** 0.0007

(0.006246)

GDP_MX1 0.0000146*** 0.0000

(0.000002)

I_USA 2.220863 0.3969

(2.609809)

I_MX1 -0.358285 0.2605

(0.316538)

E1 -0.802523*** 0.0051

(0.280313)

INFLA1 0.48507 0.2631

(0.430914)

1 Means first differences. *** Significance at 1%.

Source: Own elaboration.

However, the results of table 2 show that the GDP

of the United States, the GDP of Mexico, and the real

exchange rate Mexico-United States, present signs

contrary to those indicated by the theory, since the

first presents a negative sign instead of positive and

the second has a positive sign instead of negative,

while the third has a negative sign instead of positive.

Therefore, we resort to two additional econometric

models.

4.2 Autoregressive Vector Model

(VAR)

This model approximates the relationships between

variables in the absence of consolidated theories

since its starting point is an atheoretical approach in

which endogenous variables (those that can be

determined within the VAR System) and exogenous

variables (those that cannot be determined within

the VAR System), can be separated. The variables

that can be considered endogenous in our study are

the economic and financial variables that can be

determined in Mexico (the GDP of Mexico, the

interest rate of Mexico, the real exchange rate

Mexico-United States and the inflation rate of

Mexico), while those that can be considered

exogenous are the economic and financial variables

that cannot be determined in Mexico (the GDP of

the United States and the interest rate of the United

States).

In this result, we have a consistency in the

variables that we can consider relevant to explain

remittances, but the sign of the coefficient is

different. This model implies that the variables to be

considered to explain the behaviour of remittances

in Mexico are remittances with a lag, the GDP of

Mexico, also lagged, and the GDP of the United

States, which was considered as an exogenous

variable. It is important to mention that in this model

the coefficient of GDP in Mexico is negative, so we

can conclude that if the Mexican economy is

decreasing, this would generate a positive impact on

remittances as we might expect; Furthermore, if the

Mexican economy is growing, this would reduce the

number of dollars that families from the United

States send to Mexico (see table 3).

Determinants of International Remittances in Mexico: Economic vs. Financial Variables

39

Table 3: Autoregressive Vector Model

2

.

REM GDP_MX

REM (-1) 0.789223*** -7328.068

(

-0.11654

)

(

-5310.1

)

[ 6.77220] [-1.38003]

REM (-2) -0.010786 -8195.205

(

-0.10752

)

(

-4899.06

)

[-0.10032] [-1.67281]

GDP

_

MX

(

-1

)

-8.36E-06*** 0.077423

(-1.70E-06) (-0.07731)

[-4.92485] [ 1.00143]

GDP_MX(-2) 1.46E-06 0.283554***

(

-1.70E-06

)

(

-0.07787

)

[ 0.85425] [ 3.64127]

I

_

MX

(

-1

)

0.193817 -7784.688

(-0.327) (-14899.9)

[ 0.59271] [-0.52247]

I_MX(-2) -0.298265 -21240.35

(

-0.27623

)

(

-12586.3

)

[-1.07978] [-1.68757]

E(-1) -0.046661 -36398.56***

(

-0.22199

)

(

-10115.1

)

[-0.21019] [-3.59843]

E

(

-2

)

-0.070827 5487.444

(-0.25307) (-11531.1)

[-0.27987] [ 0.47588]

INFLA(-1) -0.211047 31892.12

(

-0.55685

)

(

-25373.1

)

[-0.37900] [ 1.25693]

INFLA

(

-2

)

0.118928 4977.638

(-0.38656) (-17613.6)

[ 0.30766] [ 0.28260]

C -23.77136 -3574679***

(

-16.9567

)

(

-772634

)

[-1.40189] [-4.62661]

GDP_USA 0.009775*** 1056.643***

(

-0.0031

)

(

-141.153

)

[ 3.15548] [ 7.48579]

I

_

USA 0.919247 47418.13

(-0.59854) (-27272.6)

[ 1.53581] [ 1.73868]

2

In Table 3 of the VAR model, due to lack of space, only

the variable Remittances, which is the variable of interest

in our study, as well as one of the endogenous variables,

which is the GDP of Mexico, are included on the

REM GDP

_

MX

R-square

d

0.932731 0.981124

Adj. R-square

d

0.923861 0.978635

Standard errors in ( ) and t-statistics in [ ].*** Significance at 1%.

(-1) and (-2) means first and second lags.

Source: Own elaboration.

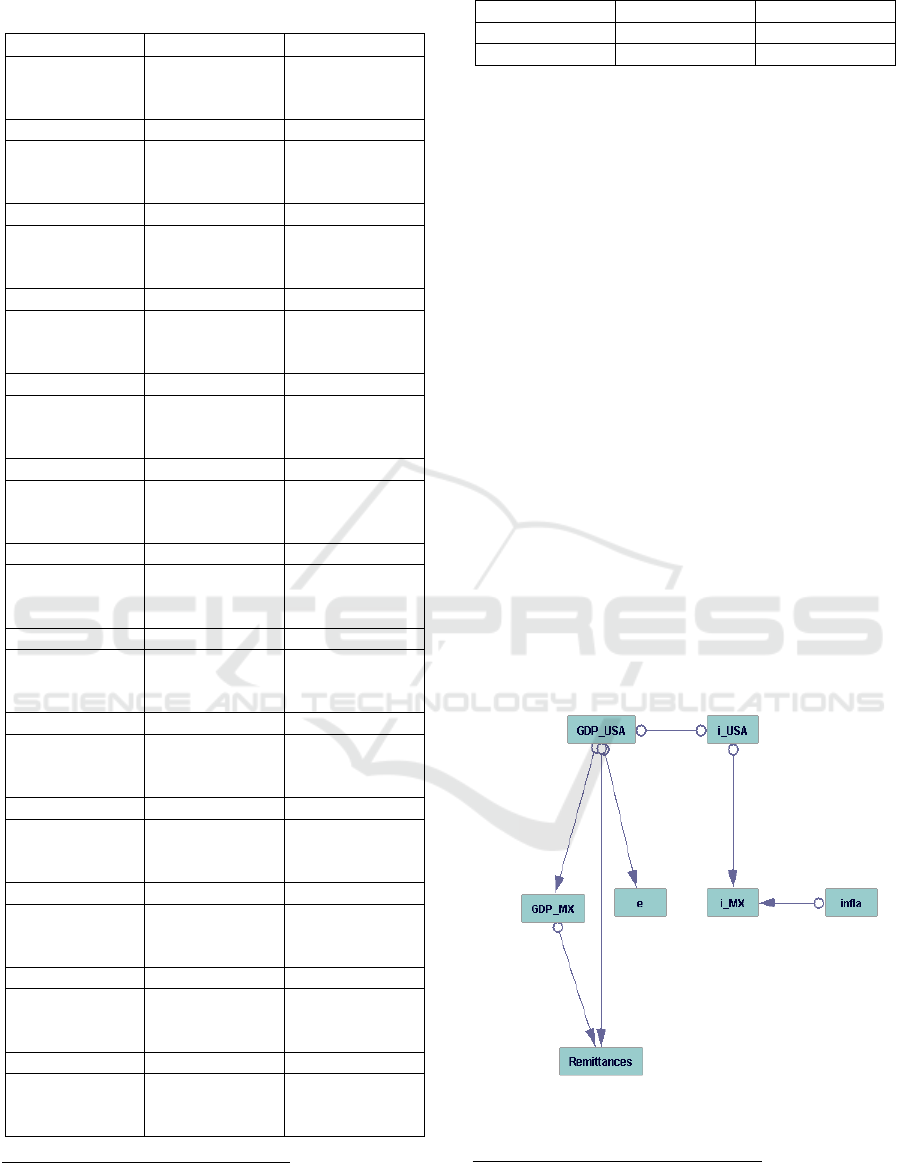

4.3 Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)

This methodology is based on the concept of

conditional correlation, to estimate the causality

among variables. Towards estimating the causality, it

is possible to use a computer algorithm called Tetrad

6, the result of which is a graph that represents the

analyzed variables and the vectors with direction

between these variables, which represent causality.

Likewise, it is possible to establish restrictions at

different levels; For example, for the variables used

we establish as level 1 the variables exogenous to the

model, which are the GDP and interest rate variables

for the US economy. In the second level, we have the

endogenous variables to the model, which are the

GDP, the interest rate, the real exchange rate, and the

inflation rate for the Mexican economy, and the last

level is the variable that we want to explain: the

remittances. For a more detailed explanation of the

process see Vera (2021) and for recent references on

this methodology see Dutta and Saha (2021), Moon

and Seok (2021), and Wang et al., (2021).

Using the data proposed by DAG we estimate the

graph in figure 1.

Figure 1: Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG).

horizontal axis. leaving out the rest of endogenous variables

(the interest rate in Mexico, the real exchange rate

Mexico-United States and the inflation rate in Mexico.

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

40

The latter implies that the only variables that we

can consider a true cause of remittances in Mexico are

GDP in the USA and GDP in Mexico, so from here

we can make a regression to estimate the signs and

parameters of this relationship, being our final result

the one shown in table 4.

Table 4: Main causes of Remittances.

Variable Coefficient

p

-value

C -67.67461*** 0.000

(10.58002)

GDP

_

USA 0.026082*** 0.000

(0.003526)

GDP_MX 0.0000175*** 0.000

(

0.00000346

)

*** Significance at 1%.

Fuente: Own elaboration.

The signs of the variables are as we expected, if

the Mexican economy is declining, migrants are

willing to send more remittances. Also, if the US

economy is growing, migrants send more

remittances.

4.4 Discussion of Results

Regarding the studies carried out for Mexico, it

should be noted that our results agree with those

obtained by Castillo (2001) and Salas and Pérez

(2006), regarding the positive relationship between

remittances and the GDP of the United States, and

negative between the remittances and Mexico's GDP,

and with Castillo (2001) regarding the negative

relationship between remittances and the real

exchange rate. However, our results do not agree with

the results of Islas and Moreno (2011), who find that

remittances are the consequence of an investment

decision rather than altruism on the part of migrants,

since the impact of interest rates is clearer than that of

Gross Domestic Product.

Also, regarding the studies carried out for other

countries, our results agree with those obtained by

Suamy (1981) for Turkey, Yugoslavia, and Greece,

by Elbadawi and Rocha (1992) for Morocco,

Portugal, Tunisia, Turkey, and the former

Yugoslavia., Sakka and McNabb (1999) for Egypt,

who found that economic activity in remittance

recipient countries significantly and positively affects

remittance flows; Likewise, they agree with those

obtained by Tuncan, Neyapti, and Metin-Ozca (2005)

for Turkey, regarding the positive impact of income

in the host country on remittances and the negative

impact of income from the country of origin on

remittances.

However, our results do not agree with those

obtained by Vargas-Silva and Huang (2005) in that

remittances respond more to changes in the

macroeconomic conditions of the host country

(income, etc.) than to changes in the macroeconomic

conditions of the home country (income, etc.), since

our results show that the macroeconomic conditions

of both the host country and the country of origin of

the migrants affect remittances.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study agree with those obtained in

most of the existing studies on the positive impact of

the Gross Domestic Product of the migrant host

country on remittances and the negative impact of the

Gross Domestic Product of the migrants' home

country on the remittances, so we can conclude that

remittances are considerably related to the economic

variables of the host countries and the origin of the

migrants.

However, our results differ from those found in

other studies, regarding the importance of financial

variables in determining remittances, since we have

found that the variables that really have a causal

relationship with remittances are the economic

variables, such as Gross Domestic Product and not the

variables of the financial sector such as the interest

rate and the real exchange rate in addition to the

inflation rate. We can imply that since the amounts

earned by migrants are just enough to survive in many

cases, financial decisions like investments or interest

rate opportunities are not considered in their decision

process.

Finally, we recognize the limitations of our study,

since we have not considered in our models other

variables that are related to remittances, in some cases

due to lack of information.

REFERENCES

Banxico (2021). Ingresos por Remesas. Sistema de

Información Ecoómica. Banco de México. Disponible

en: https://www.banxico.org.mx/SieInternet/consultar

DirectorioInternetAction.do?accion=consultarCuadro

&idCuadro=CE81&locale=es

Canales, A. (2006). Remesas y desarrollo en México. Una

visión crítica desde la macroeconomía. Papeles de

Población, vol. 12, No. 50, oct./dic. 171-196.

Castillo, R. (2001). Remesas: un análisis de cointegración

para el caso de México, Frontera Norte, Vol. 13, Núm.

26, julio-diciembre, pp. 31-50.

Determinants of International Remittances in Mexico: Economic vs. Financial Variables

41

Djajic, S. (1989). Migrants in a Guest-Worker System,

Journal of Development Economics, 31.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(89)90017-5

Dutta, K. D., & Saha, M. (2021). Nexus of governance,

macroprudential policy and financial risk: cross-

country evidence. Economic Change & Restructuring,

54(4), 1253–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-

09301-9

Elbadawi, I. y R. de R. Rocha (1995). Determinants of

Expatriate Workers’ Remittances in North Africa and

Europe. World Bank Working Paper, WPS 1038.

El Sakka, M. y R. McNabb (1999). The Macroeconomic

Determinants of Emigrant Remittances, World

Development, Vol. 27, No. 8, pp. 1493-1502.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-750x(99)00067-4

Glytsos, N. y L. Katseli (1986). Theoretical and Empirical

Determinants of International Labor Mobility: A

Greek-German Perspective. Center for Economic

Policy Research, Discussion Paper Series No. 148,

October.

Islas, A. y S. Moreno (2011). Determinantes del flujo de

remesas en México, un análisis empírico.

EconoQuantum, Vol. 7, Núm. 2.

https://doi.org/10.18381/eq.v7i2.113

Moon, H., & Seok, J. H. (2021). Price relationship among

domestic and imported beef products in South Korea.

Empirical Economics, 61(6), 3541–3555.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02014-6

Rapoport, H. y F. Docquier (2005). The Economics of

Migrants’ Remittances. IZA Discussion Paper No.

1531. March.

Salas, R. y M. Pérez (2006). Determinantes

macroeconómicos de las remesas y su efecto en la

distribución del ingreso en México. Economía y

Sociedad, vol. XI, núm. 18, julio-diciembre, p. 0.

https://doi.org/10.1787/888933146872

Swamy, G. (1981). International Migrant Workers´

Remittances: Issues and Prospects. World Bank Staff

Working Paper No. 481.

Tuncay, O., B. Neyapti y K. Metin-Ozcan (2005).

Determinants of Workers’ Remittances: The Case of

Turkey. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade.

February.

Valdivia, M., M.A. Mendoza, L. Quintana, C. Salas y F.

Lozano (2020). Impacto del COVID-19 en las remesas

y sus efectos contracíclicos en las economías regionales

en México. Contaduría y Administración, 65(5).

Especial COVID-19, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.22201/

fca.24488410e.2020.3025

Vargas-Silva, C. y Huang, P. (2005). Macroeconomic

Determinants of Workers´Remittances: Host vs. Home

Country’s Economic Conditions. Journal of

International Trade and Economic Development,

February. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638190500525779

Vera, F. (2021) “Social or economic variables? Which one

reduces poverty? A causality approach”. London

Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences,

Vol:21, issue:2, compilation:1, ISSN 2515-5784.

Wang, X., Wang, H., Wang, Z., Lu, S., & Fan, Y. (2021).

Risk spillover network structure learning for correlated

financial assets: A directed acyclic graph approach.

Information Sciences, 580, 152–173.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2021.08.072

https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496x.2005.11052609

FEMIB 2022 - 4th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

42