The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for

Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

Mariam Jacobs-Basadien

a

and Shaun Pather

b

Department of Information Systems, University of the Western Cape, Robert Sobukwe Road, Belville, South Africa

Keywords: Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2), Self-Management, Culture, Technology

Adoption, Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions.

Abstract: There are increasing calls to harness Information and Communications Technology (ICTs) more effectively

towards the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through innovative digital health

strategies. Diabetes mellitus, is one example of a global health problem that is increasing rapidly, affecting

the poor and disadvantaged populations the most. Self-care practices for diabetes self-management are

important to implement in one’s daily life as morbidity and mortality are preventable. Diabetes complications

and early fatalities are preventable through proper diabetes management and lifestyle modification. Mobile

health applications have been proposed as an important emergent technology to assist in self-care activities

of diabetes patients. However, the uptake and usage of mobile health (m-health) applications for self-

management of disease is low, especially among communities who are considered to be poor and

economically marginalised. This paper posits that individual’s culture persuasions have an influence on

diabetes patient’s decision to adopt and use mobile applications for diabetes self-management. A conceptual

framework is developed to understand the role of culture in the adoption of m-health mobile applications for

the self-management of disease.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of mobile phone, mobile-health (m-

health) has increasingly come under focus of health

care systems around the world as a means of

transforming the way health care is managed and

delivered. m-Health has therefore become prominent

in the literature emerging as a central element of

electronic health (e-health). M-health applications

can serve as a useful tool in the health care sector, as

they can help people manage their chronic conditions.

The literature provides evidence that it is a useful tool

to be used to decrease Non-Communicable Disease

(NCD) risk factors (Zhao et al., 2016). For example

Waki et al. (2014) aver that it plays an important role

in supporting the achievement of health-related goals

such as improving glycaemic levels of diabetes

patients. The American Association of Diabetes

Educators (AADE) (1997) which includes healthy

eating, being active, monitoring, taking medication,

problem solving, healthy coping, and reducing risks

is important for successful self-management.

a

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0003-4177-550X

b

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-4667-222X

However, for any individual to self-manage their

conditions, they have to first accept and use the

technology (Dou et al., 2017). However, there are

indications of levels of low uptake and use of

Information and Communication Technologies

(ICTs) among people with NCDs who are from poor

and under-resourced communities. While diabetes

affects all population groups, the demographic data

indicates that the elderly have more difficulty in using

mobile applications to manage their diabetes

(Petersen, et al., 2019).

There are several factors that have an influence on

the adoption of technology, including those in

relation to culture. For example, globally, people

have different traditions, values, religious practices

eating habits and social customs. Therefore, these

factors point to there being additional influences that

affect the adoption of mobile health (m-health)

applications (Abdulrehman et al., 2016; Ung, 2017).

According to Dehzad et al. (2014), cultural beliefs of

people are known to be key factors that influence

technology uptake and adoption. Essentially, the

Jacobs-Basadien, M. and Pather, S.

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework.

DOI: 10.5220/0011039300003188

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2022), pages 37-49

ISBN: 978-989-758-566-1; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

37

cultural background influences a number of aspects of

people’s lives, including beliefs, behaviour, perception

and attitudes towards health (Swierad et al., 2017).

Researchers have investigated culture and the role

of cultural differences in the adoption and acceptance

of Information Technology. Research indicates that

cultural backgrounds play an imperative role in

affecting the uptake and use of technology (Al-

jumeily & Hussain, 2014; Masimba et al., 2019;

Tarhini et al., 2017). These studies illustrate that

cultural backgrounds play an imperative role in

influencing the uptake and use of technology

(Masimba et al., 2019). While there are ample studies

in the literature regarding technology adoption in

varying contexts, there is a dearth of understanding

concerning adoption in the context of Non-

Communicable Disease management. Importantly,

the notion of culture in relation to mobile technology

use, for a personal diseases management is closely

linked to factors that are of an individualised nature,

such as one’s cultural persuasions. However there is

scant evidence to date to understand the latter. While

there is ample understanding of technology adoption

constructs, and a fair understanding of the concept of

culture, there is no research that has conceptually

aligned the two concepts. This is the central problem

this paper addresses by presenting a framework to

understand the role of culture in application adoption

for self-management of health.

The paper is organized as follows: First, the

technology adoption models are discussed. Second,

culture and the cultural models are identified.

Thereafter, the technology adoption models are

compared and the cultural models; Two of the often

cited research are assessed and compared with each

other, viz. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (1980,

2010) and Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner cultural

model (1997). Subsequently, understanding culture

within a country context is discussed. Next, the

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of

Technology 2 (Venkatesh et al., 2012) is mapped

against Hofstede’s cultural dimensions to identify the

relationships between them. This is the foundation on

which a conceptual model is derived.

2 USER ACCEPTANCE OF

TECHNOLOGY MODELS

Technology acceptance is defined as a user’s

intention to use and continue making use of a

particular IT product (Davis, 1989) (e.g., a mobile

phone or computer).

Technology acceptance has been an important

subject in IS research. It has been studied since the

1970s in the field of computer science where studying

the adoption, acceptance and use of Information

Systems (IS) is an area of study in the software

engineering field (Momani & Jamous, 2017). The

mainstreaming of technology and the importance of

the people dimension in terms of gaining benefit from

the use of technology rose to the fore when

researchers such as Venkatesh et al. (2003) found that

users were not deriving benefits from technology.

Historically, this area of research focuses on the

problem that the availability of technology does not

necessarily convert into adoption and use.

Understanding the reasons why users accept or reject

information technology is one of the crucial areas in

IS research (Venkatesh et al., 2007). In the study of

m-health acceptance, understanding technology

adoption and usage is essential. Venkatesh et al.

(2016) have stated that users must first use

technology before the desired outcome can be

achieved.

Technology adoption models have been

developed to understand how users understand,

accept and use technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

In addition, these models introduce factors that can

affect user decisions to adopt new technologies.

Models such as the technology acceptance model

(TAM) developed by (Davis, 1989) explain user

acceptance of new technologies. Even though there

have been many studies conducted using technology

adoption models, it is crucial to understand how the

models have evolved throughout the years as this

reveals the similarities and differences between them.

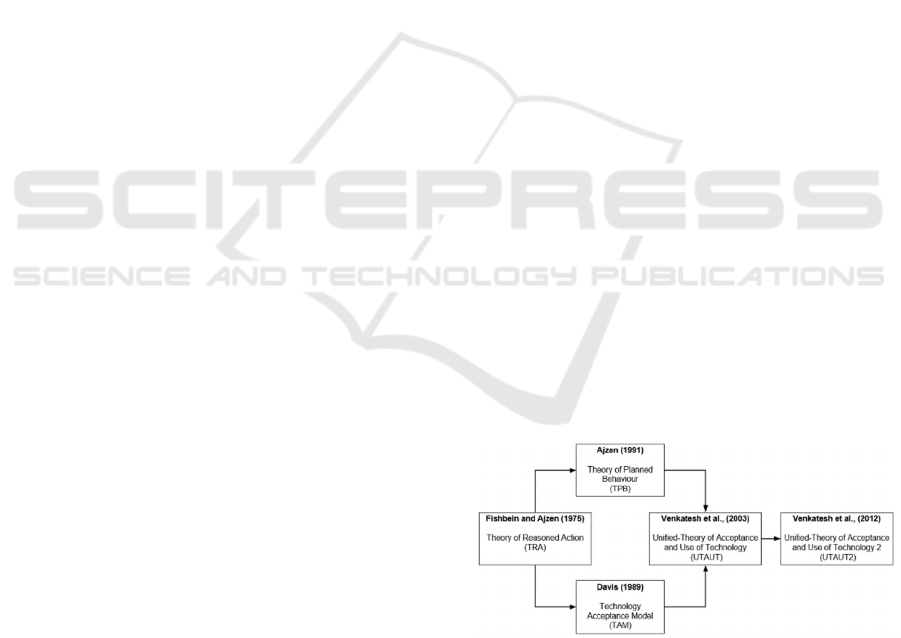

Figure 1 represents the dominant technology adoption

models in the area of m-health and how it evolved

over time.

Figure 1: The prominent technology adoption models over

time.

The above figure depicts that the Unified-Theory

of Acceptance and Use of technology (UTAUT) was

developed based on prior models such as the theory

of reasoned action (TRA), technology acceptance

model (TAM) and the theory of planned behaviour

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

38

(TPB). The UTAUT was then extended to the

UTAUT2. The similarities between the five

prominent models are discussed in Table 1 section,

section 4.

The succeeding section discusses the Unified-

Theory of Acceptance and use of Technology 2 which

is conceptually a central aspect of this study.

2.1 Unified-Theory of Acceptance and

Use of Technology 2

Unified-Theory of Acceptance and Use of

Technology (UTAUT) was believed to be a complete

model to forecast IT acceptance (Martins et al., 2014)

until Unified-Theory of Acceptance and Use of

Technology 2 was developed. The Unified- Theory of

Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 model

(UTAUT2) (Figure 2) is an extension of the UTAUT

for understanding consumer acceptance of new

technology better, and is centred on the individuals’

perspectives of technology adoption (Venkatesh et

al., 2012). The UTAUT2 includes three additional

moderators: hedonic motivation, price value and

habit.

Hedonic motivation was regarded as a significant

predictor in prior research (Venkatesh et al., 2003),

and it was integrated into the Unified-Theory of

Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) for

more stressing utilities. The price value construct was

introduced in the UTAUT2 model as the quality of

the product, cost and utility compared with the price

will in turn influence adoption decisions (Hennigs et

al., 2013). Habit is a significant predictor of mobile

internet use (Venkatesh et al., 2012, 2016) and has

appeared to be the strongest determining factor of

individual technology use (Tamilmani et al., 2020).

In the UTAUT2, habit is assumed to directly

influence both behavioural intention and use

behaviour (Hwang et al., 2016).

The UTAUT2 core constructs are defined below:

Performance Expectancy (PE): “is the degree

to which an individual believes that using the

system will help him or her to attain gains in

job performance” (Venkatesh et al., 2003,

p.447).

Effort Expectancy (EE): “is the degree of ease

associated with the use of the system”

(Venkatesh et al., 2003, p.450).

Social Influence (SI): “is the degree to which

an individual perceives that important others

believe he or she should use the new system”

(Venkatesh et al., 2003, p.451).

Facilitating Conditions (FC): “is the degree to

which an individual believes that an

organisational and technical infrastructure

exists to support the use of the system”

(Venkatesh et al., 2003, p.453).

Hedonic Motivation (HM): is defined as “the

fun or pleasure derived from using a

technology” (Venkatesh et al., 2012, p.161).

Price Value (PV): is defined as “consumers’

cognitive trade-offs between the perceived

benefits of the applications and monetary costs

for using them” (Venkatesh et al., 2012,

p.161).

Habit (HT): “the extent to which people tend

to perform behaviours automatically because

of learning” (Venkatesh et al., 2012, p.161).

The UTAUT2 model has been used to explore

various research problems such as health applications

(Dwivedi et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2015; Pancar &

Ozkan Yildirim, 2021) and technology adoption and

culture (Baptista & Oliveira, 2015; Lai et al., 2016;

Tarhini et al., 2017; Teo & Huang, 2018).

Figure 2: The Unified-Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (Source: Venkatesh et al., 2012, p.160).

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

39

3 MODELS OF CULTURE

Having set a foundational understanding of

technology acceptance in the previous section, the

next consideration is to understand culture. Amongst

other essential points identified in the literature, the

notion of culture was identified as being one of the

main conceptual gaps in one of the most often applied

models, viz. the Unified-Theory of Acceptance and

Use of Technology model (UTAUT).

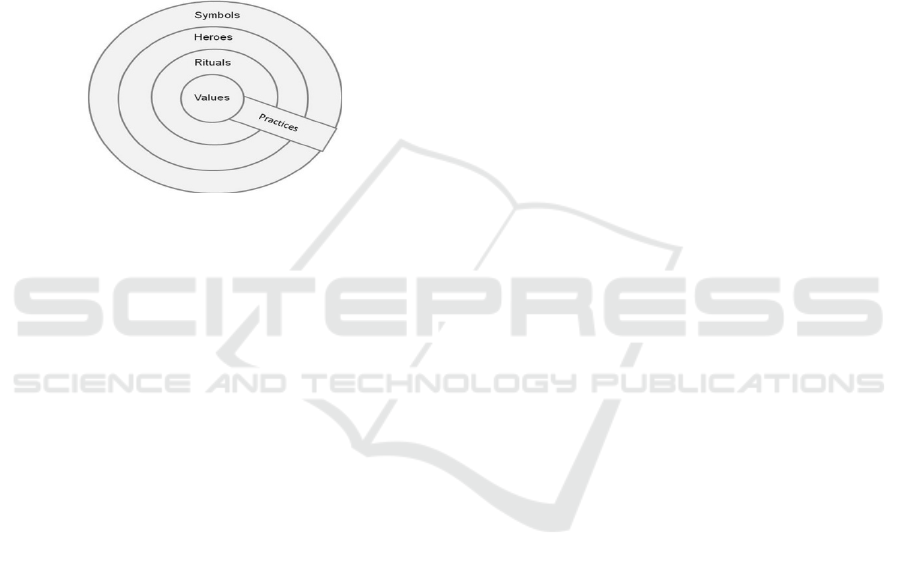

According to Hofstede et al. (2010), cultural

differences are displayed on different levels of depth

such as symbols, heroes, rituals and values (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The “Onion”: Manifestations of Culture at

Different Levels of Depth (Source: Hofstede et al. (2010,

p.8)).

The levels of depth are defined below by Hofstede et

al. (2010, p.8-9) :

Symbols: In the first, outermost layer, are pictures,

words and jargons that contain a specific meaning

that is understood by those people who form part of

the same culture.

Heroes: The second layer is defined as people

dead or alive that possesses qualities that are glorified

by people in a particular society, for example, Nelson

Mandela, the first president post- apartheid.

Rituals: The third layer is collective activities that

are seen as socially essential. The ways of greeting,

social and religious ceremonies are examples of

rituals.

Values: The fourth, innermost layer, are wide-

ranging terms that prefer certain states as opposed to

others, for example, good rather than evil.

Hofstede et al., (2010) argue that culture is

learned and not inherent. By the term “learned” they

indicate that people’s culture is adopted by the effect

of social values and personal incidents that are unique

to an individual (Hofstede et al., 2010). However, it

is argued that even though individual members

perceive culture based on what they see or hear,

culture can also be transmitted consciously or

unconsciously from one generation to another.

Beukman (2005) states that culture is two

dimensional. It can either be explicit or implicit.

Explicit consists of behavioural patterns in a given

situation and implicit is a manifestation of attitudes,

values, beliefs, and norms, which collectively give

meaning to explicit behaviour.

Hofstede posits that culture is made up of six

different layers. It can exist at a “national level or

country level, a regional and/or ethnic and/or

religious level, a gender level, a social class level, an

organisational level, and lastly an individual level”

(Hofstede et al., 2010, p.18). At a country level,

culture functions through religions, languages, and

social structures (Hassan et al., 2016). Some markers

distinguish one individual from another in a given

society such as their demographics, educational

background, religion, location and income status

(Hodgetts et al., 2005).

As culture exists differently in all parts of the

world, American, Asian, European and African

culture is unique in all forms and expressions (Yavwa

& Twinomurinzi, 2018). Culture, as a social concept,

has been studied for many years. Research findings

have found that there is a link between culture and

technology adoption. Culture can either impede

technology adoption (Hasan & Ditsa, 1999) or can

facilitate technology acceptance (Sriwindono &

Yahya, 2012). It is, therefore, vital to incorporate

culture into the models of user acceptance.

3.1 Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede’s definition of culture is broad and has been

widely accepted in IS literature. He defines culture as

“the collective programming of the mind which

distinguishes the members of one human group from

another” (Hofstede, 1980, p.13). Hofstede (1980)

developed an index model and presented four cultural

values of culture: Power Distance, Individualism

versus Collectivism, Masculinity versus Femininity,

and Uncertainty Avoidance. Hofstede then included

Long-Term versus Short-Term Orientation as a fifth

dimension (Hofstede, 2001). He later added

Indulgence versus Restraint as a sixth dimension

(Hofstede et al., 2010).

Hofstede et al. (2010) have defined cultural values

as follows:

Power Distance:

“extent to which the less

powerful members of institutions and organisations

within a country expect and accept that power is

distributed unequally” (p.61).

Individualism- collectivism: “refers to societies in

which the ties between individuals are loose:

everyone is expected to look after him or herself and

his or her immediate family. Collectivism as its

opposite pertains to societies in which people from

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

40

birth onward are integrated into strong, cohesive in-

groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue

to protect them in exchange for unquestioning

loyalty” (p.92).

Masculinity- femininity: Masculinity refers to a

“society in which emotional gender roles are clearly

distinct” (p.519). Femininity is seen as a “society in

which emotional gender roles overlap: both men and

women are supposed to be modest, tender, and

concerned with the quality of life” (p.517).

Uncertainty avoidance: “the extent to which the

members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or

unknown situations” (p.191).

Long-term orientation- Short-term orientation:

“the fostering of virtues oriented toward future

rewards—in particular, perseverance and thrift”

(p.239). Short-term orientation “the fostering of

virtues related to the past and present—in particular,

respect for tradition, preservation of face, and

fulfilling social obligations” (p.239).

Indulgence- restraint: Indulgence refers to a

“society that allows relatively free gratification of

basic and natural human desires related to enjoying

life and having fun” (p.519). Restraint refers to a

“society that suppresses gratification of needs and

regulates it by means of strict social norms” (p.521).

Hofstede’s culture framework has been

extensively studied in the areas of Information

Systems (IS) and Information Technology (IT)

studies (e.g. (Lee et al., 2013; Sriwindono & Yahya,

2012, 2014; Tarhini et al., 2017)). These studies

suggest that a significant relationship exists amongst

national culture and the rate of technology adoption

and acceptance.

In a study carried out by Sriwindono & Yahya,

(2012), long-term orientation has been found to have

the highest effect on perceived usefulness of

technology, then followed by power distance and

individualism on perceived ease of use of technology.

Although Hofstede’s cultural values have been

influential in many disciplines, they have not escaped

criticism. Hofstede work has been criticised for a lack

of generalisability and over- simplifying culture (Ng

et al., 2007). Furthermore, Hofstede (1980) stated that

a country-level analysis is unable to predict individual

behaviour. However, national cultural values have

been examined as being espoused at the individual

level in previous research (Srite & Karahanna, 2006;

Sun et al., 2019; Teo & Huang, 2018). Later,

Hofstede recommended that culture should be

investigated at the social level and values should be

studied at the individual level (Hofstede, 2001). He

further claimed that cultural values are the foundation

of daily practices (Figure 3 - the onion model), and

daily practice was affected by a person’s cultural

values (Hofstede, 2001).

The application of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

to diabetes patients self-care behaviour activities are

discussed in the appendix.

3.2 Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner

Cultural Dimensions

Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner (1997) cultural

model was developed to explain cultural differences

based on the challenges people encounter when

forming social communities. According to

Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, “culture is the way

in which a group of people solve problems and

reconcile dilemmas” (Trompenaars & Hampden-

Turner, 1997, p.6). They further state that preferences

differentiate people into various cultural dimensions.

These dimensions were then developed to illustrate

the differences between one culture compared to

another and how culture relates to societal level

characteristics. The dimensions illustrated by this

model are useful in comprehending how people from

different national cultures interact.

The Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner (1997)

model consist of seven dimensions:

Individualism versus Communitarianism: In

Individualism describes cultures where ties between

individuals are loose. The individual rather than any

group norms determine decision making on lifestyle.

In Communitarian cultures, groups are considered to

be the most important, unlike individuals. As

Communitarian refers to groups, rewards are given to

group performance, decisions are taken collectively,

and individual performances are not publicly praised

(p.9).

Universalism versus Particularism: In a

Universalistic culture, people abide by standards that

are collectively decided upon by all who form part of

this culture. This culture consists of laws, values and

rules and which are applied to everyone.

Alternatively, in Particularistic cultures, personal

relationships are valued as a substitute for laws and

rules (p.8).

Specific versus Diffuse: In specific culture, people

believe that their private lives ought to be kept

separate from their professional lives. In diffuse

oriented culture, personal and professional

relationships overlap (p.9).

Affectivity versus Neutrality: In Affectivity

cultures, people are allowed to display their emotions

to others and may partially allow emotions to

influence their decision. While in neutral cultures,

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

41

individuals should practice self-control regarding

their emotions (p.69).

Internal direction versus External direction: In

internal-directed cultures, to achieve goals people

deem that they can control their surroundings while

in external direction, people deem that they are

controlled by their surroundings.

Achieved Status versus Ascribed Status: In

achievement cultures, status is given based on how

well people perform at a particular task. While in

Ascription culture, people are endorsed on what or

who they are. Status may be conferred according to

demographics, family and racial group (p.102).

Sequential Time versus Synchronic Time: In a

sequential time culture, people tend to be inflexible.

The sequence of events is of utmost importance in this

regard, as individuals value planning and punctuality

as imperative. In contrast, people who view plans and

obligations as flexible form part of a Synchronic time

as they work on multiple tasks at once (p.124).

An assessment of the above indicates that, in

relation to the study, Trompenaars & Hampden-

Turner (1997) cultural dimensions may be a relevant

model to study culture in this context. The application

of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner cultural model

to diabetes patients’ self-care activities are discussed

in the appendix.

The similarities between Trompenaars &

Hampden-Turner cultural model and Hofstede’s

cultural dimensions are discussed in the next section

(section 4, Table 2).

4 COMPARISON OF USER

ACCEPTANCE MODELS AND

CULTURAL MODELS

Table 1 presents the five prominent models. This

includes the key constructs of the user acceptance

model who were found to have some alignment to the

study research problem.

Through the comparison of the user acceptance

models, the TRA is similar to that of the TPB. The

TPB can be compared to the UTAUT model as the

key constructs (PE, EE and Social Influence) of the

UTAUT model is similar to that of the TPB model.

An examination of the definitions of the constructs

indicates that “attitude” represents “performance

expectancy” and “effort expectancy” constructs in the

UTAUT model because PE and EE are attitudinal

constructs. “Subjective norm” in the TAM is similar

to the Social Influence (SI) construct in the UTAUT

model, and the “perceived behavioural control”

Table 1: Comparison of the user acceptance model.

TRA

TPB

TAM

UTAUT

UTAUT 2

Key constructs

Attitude

towards

behaviour (A)

✔

✔

PU

P

E and

EE

PE and

EE

Subjective

norms (SN)

✔

✔

SI

S

I

Perceived

behavioural

control (PBC)

✔

PEOU EE EE

Perceived ease

of use (PEOU)

PBC

✔

EE EE

Perceived

usefulness

(PU)

A

✔

PE PE

Performance

expectancy

(PE)

✔

✔

Effort

expectancy

(EE)

✔

✔

Social

influence (SI)

✔

✔

Facilitating

conditions

(FC)

✔

✔

✔

Hedonic

Motivation

(HM)

✔

Price value

(PV)

✔

Habit (H)

✔

construct is similar to that of facilitating conditions in

the UTAUT model (Sun et al., 2013). Furthermore,

both the TPB and UTAUT models have been used in

the area of health research and Information

Technology adoption.

Table 2 presents the similarities between

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and Trompenaars &

Hampden-Turner’s cultural model.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

42

Table 2: Comparison of Hofstede's cultural dimensions and

Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner cultural model.

Hofstede

cultural

dimensions

Trompenaars

& Hampden-

Turner

Cultural

model

Dimensions of culture

Power

Distance

✔

Individualism -collectivism

✔ ✔

Masculinity -Femininity

✔

Similar to

affectivity/

neutralit

y

Uncertainty

avoidance

✔

Long term orientation -

Short term orientation

✔

Indulgence -Restraint

✔

Individualism vs

communitarianism

Similar to

Individualism

-collectivis

m

✔

Universalism versus

Particularism

✔

Specific versus Diffuse

✔

Affectivity versus Neutrality

✔

N

ature Orientation

✔

Achieved Status versus

Ascribed Status

✔

Sequential Time versus

S

y

nchronic Time

✔

In regard to the cultural dimensions, Trompenaars &

Hampden-Turner, individualism versus

communitarianism and universalism versus

particularism dimensions are similar to Hofstede’s

cultural individualism– collectivism dimensions. In

addition, affectivity versus neutrality is similar to

Hofstede’s cultural masculinity–femininity. As

previously mentioned, Hofstede’s constructs have

been used to study the relationship between culture

and technology adoption. Based on the cultural

dimension of individualism versus collectivism,

culture may likely have some influence on attitude

toward technology use (Bandyopadhyay &

Fraccastoro, 2007).

Both men and women can exhibit masculine and

feminine traits (Cyr et al., 2017) and this can

influence technology adoption. Furthermore,

Hofstede’s construct, uncertainty avoidance has

received much attention in the field of technology

adoption (Özbilen, 2017). It has been found that

informational influence from family can encourage

people in uncertainty avoidance cultures to adopt and

use technologies (Alhirz & Sajeev, 2015). On the

other hand, Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner (1997)

has received little attention. Furthermore, this

framework does not provide an applied approach to

measure culture (Su & Sauers, 2009).

5 INTEGRATING CULTURE AT

AN INDIVIDUAL LEVEL WITH

THE MODELS FOR USER

ACCEPTANCE

Table 3 represents the user acceptance models that

have been used together with cultural models to

answer various research questions

Table 3: Studies on culture and technology in different

contexts.

Author

Constructs used in this

study

Methodology

and models

used

Sun et al.

(2019)

Individual-level Culture

Hofstede cultural

dimensions Perceived

usefulness

Perceived ease of use

Technology

Acceptance

Model Hofstede

Questionnaire

Zhang et

al. (2018)

Performance expectancy

Effort expectancy

Social influence

Perceived risk Trust

Hofstede’s cultural

dimensions

Unified- Theory

of Acceptance

and Use of

Technology

Hofstede’s

cultural

dimensions

Questionnaire

Teo &

Huang

(2018)

Hofstede cultural

dimensions Perceived

ease of use Perceived

Usefulness

Attitude towards use

Behavioural intention

Extended

Technology

Acceptance

Model

Hofstede

cultural Model

Questionnaire

Lu et al.

(2017)

Age, gender, experience

Hofstede’s cultural

dimensions Perceived

effort expectancy

Perceived performance

expectancy

Perceived mobile social

influence Perceived

privacy protection

Espoused

cultural

dimension of

Hofstede

Unified- Theory

of Acceptance

and Use of

Technology

Questionnaire

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

43

Table 3: Studies on culture and technology in different

contexts (cont.).

Author

Constructs used in this

study

Methodology

and models

used

Tarhini et

al. (2017)

Individual-level culture

Perceived ease of use

Subjective norms

quality of work-life

Behavioural Intention

Technology

Acceptance

Model

Questionnaire

Lai et al.,

(2016)

Long-term orientation

Collectivism

Power Distance

Uncertainty avoidance

Performance expectancy

Effort expectancy

Social influence Hedonic

Motivation

Facilitating conditions

Hofstede

cultural

dimensions

UTAUT2

Survey

Baptista &

Oliveira,

(2015)

UTAUT2

Hofstede cultural

dimensions Behavioural

intention

Use behaviour

UTAUT2

Hofstede

cultural

dimensions

Questionnaire

Hoehle et

al. (2015)

Uncertainty avoidance,

Perceived usefulness

Perceived ease of use

Perceived usefulness

Collected data

from consumers

using ICT in

four countries,

Hofstede

cultural

dimensions

Al-jumeily

&

Hussain,

(2014)

Individualism-

Collectivism, Uncertainty

Avoidance

Power Distance

Perceived usefulness

Perceived ease of use

Technology

Acceptance

Model Hofstede

cultural

dimensions

Survey

Al-

Gahtani et

al., (2007)

Hofstede cultural

dimensions Unified-

Theory of Acceptance

and Use of Technology

Unified-Theory

of Acceptance

and Use of

Technology

Survey

By an assessment, it can be noted that Hofstede’s

cultural dimension can be used in studies of culture

and technology adoption (Table 3). The methodology

that many of the studies adopted has been a

questionnaire method approach. Previous studies

have used the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

and the Unified-Theory of Acceptance and Use of

Technology (UTAUT) as a lens for analysis.

However, it has been found that the TAM model is

unable to forecast technology use across every culture

(Straub et al., 1997). To understand diabetes self-

management in marginalised communities,

challenges such as cultural backgrounds and beliefs

should also be considered.

Hofstede’s cultural model has been used in studies

relating to technology adoption in various contexts as

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions aid researchers to

comprehend what motivates technology adoption and

use (Hoehle et al., 2015; Leidner & Kayworth, 2006).

Additionally, Hofstede’s constructs allow scholars to

study issues in a variety of phenomena (Hoehle et al.,

2015). Literature indicates that many studies focusing

on culture and technology adoption have used

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (e.g. Srite &

Karahanna, 2006; Sun et al., 2019; Tarhini et al.,

2017). A recent study by Alam et al. (2020) explored

factors affecting the adoption of m-health in a

developed country. The authors recommend that

further research ought to be done in different socio-

economic groups, rural areas and other cultures and

groups with different religious beliefs. Petersen et al.,

(2019) suggested that further research should be

conducted on culture in the use of m‐health for

diabetes self‐ management.

6 UNDERSTANDING CULTURE

WITHIN COUNTRY

CONTEXTS

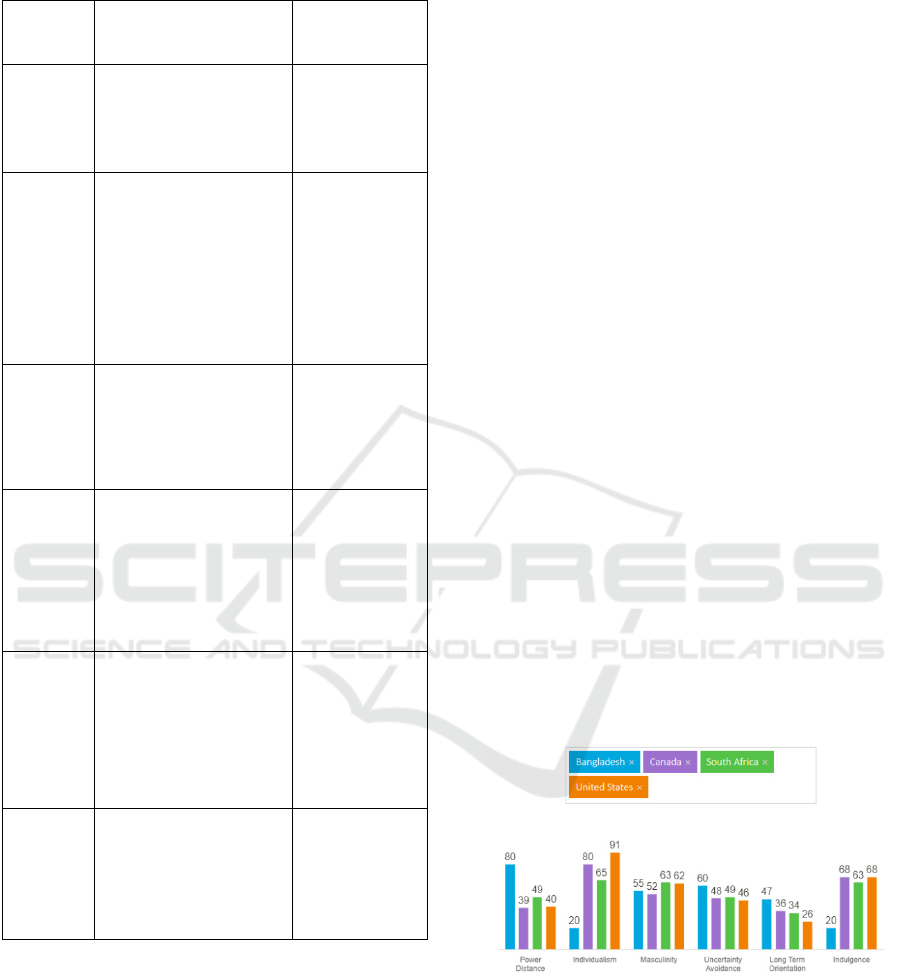

Culture manifests differently across nations. Figure 4

depicts that culture in developing countries (South

Africa and Bangladesh) differs from developing

countries (Canada and United States).

Figure 4: Hofstede's insights (Source: Hofstede, 2019).

There is a low power distance value for South

Africa, Canada, and the United States. The value

indicates that people accept hierarchical order

(Hofstede, 2019). Context-wise, diabetic patients

from low power distance countries are likely to

conform to the opinions and decisions of their health

care professional.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

44

The individualism dimension indicates that

people care for themselves and immediate family

(Hofstede, 2019). In Bangladesh, the value shows that

people conform more towards a collectivism culture.

This suggests that diabetic patients will conform to

the decisions of their society, or communities in

which they live. In the remaining countries, the data

suggests that the decisions are made at the

individual’s discretion.

The masculinity dimension indicates that people

“live to work” (Hofstede, 2019). All four countries

score high in this dimension which indicates that

individuals will prioritise work over other matters.

This for example, could imply that a diabetic patient

in such a country may not prioritise the use of tools

such as m-health applications for disease self-

management.

The uncertainty avoidance dimension indicates a

high value for Bangladesh and suggests that people in

this country fear uncertainty. A consequence of such

a cultural persuasion implies that people may shun

new technologies and innovations if the adoption and

uptake thereof is associated with uncertainty.

South Africa and the United States indicates low

long-term orientation which indicates that traditions

are more important, and change is viewed adversely.

Therefore, if one considers this cultural dimension in

the case of diabetic patients, it could imply that they

would prefer traditional face-to-face consultations

with doctors as compared to using technology to

manage their health condition.

South Africa, United States and Canada illustrates

a culture of indulgence which indicates that people in

these countries prefer having a good time and

spending their time as they wish. In the context of

this study’s problem this could imply that if persons

engage in self-care behaviour, including using

technology for it, they will ensure that they make

decisions that provide them with fulfilment and

satisfaction.

7 MAPPING UNIFIED-THEORY

OF ACCEPTANCE AND USE OF

TECHNOLOGY 2 AGAINST

HOFSTEDE’S CULTURAL

DIMENSIONS

Table 4 presents the outcome of this. It maps the

seven constructs of the Unified-Theory of

Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2)

against Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in order to

assess which of the theoretical definitions of the

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions fit against the

UTAUT2 technology adoption (as depicted by

UTAUT2) amongst diabetic patients in previously

disadvantaged communities.

Table 4: Mapping UTAUT2 constructs against Hofstede’s

cultural dimensions.

Utaut2

Hofstede

PE EE SI

FC

HM PV H

Power Distance

X

Individualism-

Collectivism

X

X

Masculinity

Femininity

X

Uncertainty

avoidance

X

X

Long term

orientation -

Short term

orientation

X

Indulgence

- Restraint

X

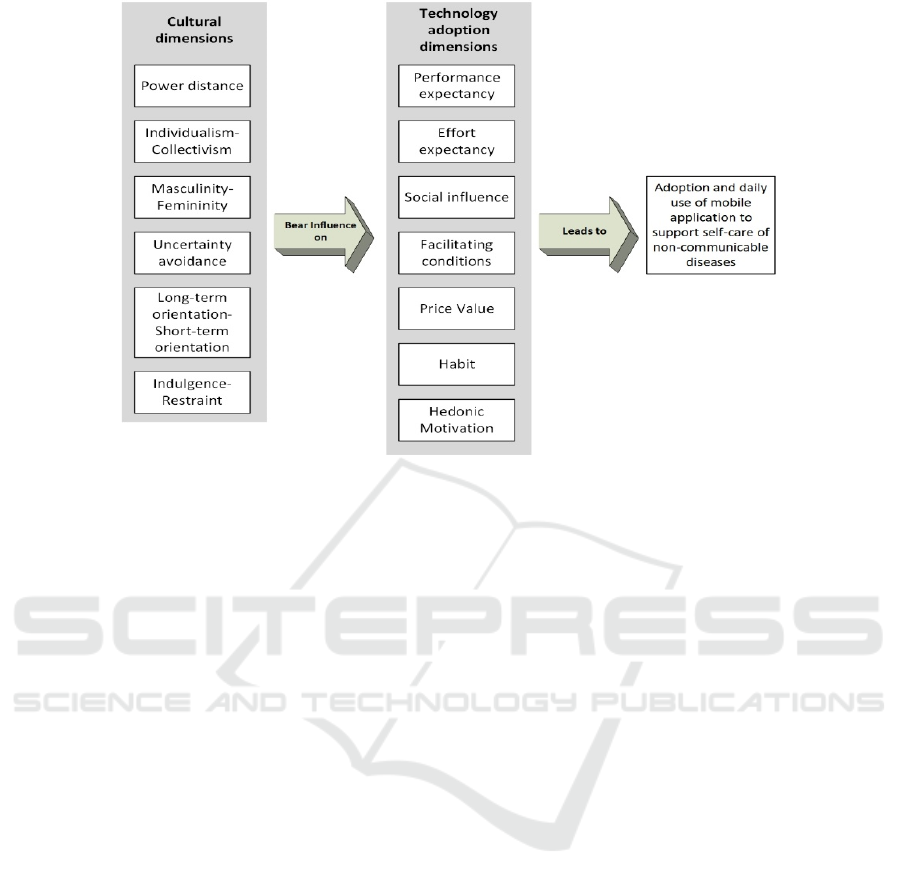

8 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The underpinning theoretical framework from the

extant literature (Figure 2) and Hofstede’s cultural

dimensions (Section 3.1) provide a basis for the

conceptual framework below. Figure 5 is conceived

from the foregoing analyses (Sections 4, 5 and 7). It

provides a conceptual foundational understanding of

how the dimensions of culture influence technology

adoption in the context of self-management of NCDs

such as diabetes.

The literature review presented evidence that the

UTAUT2 is the best suited model to study technology

adoption and culture. After reviewing literature on

culture, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions have been

deemed as an appropriate fit to study culture in the

context of technology acceptance.

Looking ahead, researchers should consider

empirical investigations into the problem area as

follows:

There are six concepts that explain the

phenomenon of culture. In investigating such

problems in the field all of these must be taken

into account to understand whether and how

diabetes patients’ culture influences their self-

care behaviours and whether their culture

influences their m-health acceptance and usage

for their self-management.

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

45

Figure 5: A conceptual framework of the role of culture on mobile technology acceptance and use.

Seven constructs drawn from the Unified-

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2

provide insight into diabetes patients acceptance

and usage of m-health to self- manage their

condition.

Finally, the AADE 7 self-behaviour activities

provide a framework of actual day to day living

of people with NCDs. These provide the

context in which to study the concepts of culture

and technology acceptance.

9 CONCLUSIONS

This paper derived a conceptual framework to explain

the problem of how culture influences technology

adoption in the context of self-care behaviour

activities. The conceptual framework can serve as a

starting point to assist policymakers and application

developers to tailor mobile applications for this target

population. In addition, this model can inform and

improve current m-health related interventions,

which could result in the improved or successful

adoption and uptake of ICT, specifically m-health

applications among diabetic patients in poor and

under-resourced communities.

The paper presents a first step to address a gap in

the literature with respect to the understanding of

culture in m-health acceptance and use for health self-

management in general, and for diabetes self-

management in particular. We conclude that to

achieve effective self-management of diabetes using

a mobile application, cultural factors that prevail on

users must be taken into consideration. Therefore this

paper contributes to a better understanding of the

nexus between culture and technology adoption. The

paper furthermore contributes towards a better

understanding of how to successfully apply ICT

towards the attainment of the UN’s Sustainable

Development Goal 3.

The next step in the research process is to use the

conceptual framework and related understandings to

inform both a mobile application design process and,

importantly, how to mitigate low adoption of an

application. By understanding the role of culture in

uptake and use of m-health applications, government,

and any other stakeholders, can be informed as to how

to mitigate low adoption scenarios, by considering the

outcomes of this study. For example, effort

expectancy points to user-centred design;

performance expectancy points to application

functionality. Many of the other dimensions point to

how potential users would uptake technology e.g.

power distance points to whether and how influential

people influence users to adopt mobile applications

and uncertainty avoidance points to whether

ambiguous situations hinder people from utilising a

mobile application.

The research framework provides us with insight

not only into potential mobile application

functionality – e.g., tracking health information. The

research model will be tested in under-resourced

communities in the Western Cape, South Africa using

a co-design approach such as that proposed by

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

46

Kyakulumbye & Pather (2022). Such marginalised

communities appear to be bearing the brunt of social

and health ills. The effective deployment of ICT

based solutions will go a long way towards

sustainable solutions to improve living conditions for

such communities.

In conclusion, the conceptual framework of this

paper can be used in the next stage of research to

undertake a further study of a mobile application

functionality requirement as needed by the aged.

That would be a first step towards creating a usable

application to be deployed in a context that accounts

for the cultural dimensions influences identified in

this paper.

REFERENCES

Abdulrehman, M. S., Woith, W., Jenkins, S., Kossman, S.,

& Hunter, G. L. (2016). Exploring Cultural Influences

of Self-Management of Diabetes in Coastal Kenya.

Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 3, 1–13.

Al-Gahtani, S. S., Hubona, G. S., & Wang, J. (2007).

Information technology (IT) in Saudi Arabia: Culture

and the acceptance and use of IT. Information and

Management, 44(8), 681–691.

Al-jumeily, D., & Hussain, A. J. (2014). The impact of

cultural factors on technology acceptance : A

technology acceptance model across Eastern and

Western cultures. International Journal of Enhanced

Research in Educational Development (IJERED), 2(4),

37–62.

Alam, M. Z., Hoque, M. R., Hu, W., & Barua, Z. (2020).

Factors influencing the adoption of mHealth services in

a developing country: A patient-centric study.

International Journal of Information Management, 50,

128–143.

Alhirz, H., & Sajeev, A. S. M. (2015). Do cultural

dimensions differentiate ERP acceptance? A study in

the context of Saudi Arabia. Information Technology

and People, 28(1), 163–194.

American Association of Diabetes Educators. (1997). Self

Care Behaviors. In Diabetes Self-Management (pp. 1–

11).

Bandyopadhyay, K., & Fraccastoro, K. A. (2007). The

Effect of Culture on User Acceptance of Information

Technology. Communications of the Association for

Information Systems, 19(23), 522–543.

Baptista, G., & Oliveira, T. (2015). Understanding mobile

banking: The unified theory of acceptance and use of

technology combined with cultural moderators.

Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 418–430.

Beukman, T. L. (2005). Chapter 3 Culture, Values and

Work-related values- a theoretical overview.

Cyr, D., Gefen, D., & Walczuch, R. (2017). Exploring the

relative impact of biological sex and masculinity–

femininity values on information technology use.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(2), 178–193.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness , Perceived Ease

of Use , and User Acceptance of lnformation

Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Dehzad, F., Hilhorst, C., de Bie, C., & Claassen, E. (2014).

Adopting Health Apps, What’s Hindering Doctors and

Patients? Health, 06(16), 2204–2217.

Dou, K., Yu, P., Deng, N., Liu, F., Guan, Y., Li, Z., Ji, Y.,

Du, N., Lu, X., & Duan, H. (2017). Patients’

Acceptance of Smartphone Health Technology for

Chronic Disease Management: A Theoretical Model

and Empirical Test. JMIR MHealth and UHealth

,

5(12).

Dwivedi, Y. K., Shareef, M. A., Simintiras, A. C., Lal, B.,

& Weerakkody, V. (2016). A generalised adoption

model for services: A cross-country comparison of

mobile health (m-health). Government Information

Quarterly, 33(1), 174–187.

Hasan, H., & Ditsa, G. (1999). The impact of culture on the

adoption of IT: An interpretive study. Journal of Global

Information Management, 7(1), 5–15.

Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., & Parry, S. (2016). Addressing the

cross-country applicability of the theory of planned

behaviour (TPB): A structured review of multi-country

TPB studies. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(1),

72–86.

Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K. P., & Klarmann, C. (2013).

Consumer value perception of luxury goods: A cross-

cultural and cross-industry comparison. In Luxury

Marketing: A Challenge for Theory and Practice (pp.

78–99). Gabler Verlag.

Hodgetts, R. M., Luthans, F., & Doh, J. (2005).

International Management: Culture, Strategy and

Behavior W/ OLC Card MP (6

th

edition). McGraw-Hill

Companies.

Hoehle, H., Zhang, X., & Venkatesh, V. (2015). An

espoused cultural perspective to understand continued

intention to use mobile applications: A four-country

study of mobile social media application usability.

European Journal of Information Systems, 24(3), 337–

359.

Hofstede. (2019). Country Comparision- Hofstede’s

Insights.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences:

International Differences in Work-related Attitudes.

Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing

Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations

Across Nations, (2

nd

edition). Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010).

Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind (3

rd

edition). Mac-Graw Hill.

Hwang, Y., Al-Arabiat, M., & Shin, D.-H. (2016).

Understanding technology acceptance in a mandatory

environment. Information Development, 32(4), 1266–

1283.

Kyakulumbye, S., & Pather, S. (2022). Understanding ICT

adoption amongst SMEs in Uganda: Towards a

participatory design model to enhance technology

diffusion. African Journal of Science, Technology,

Innovation and Development, 14(1), 49–60.

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

47

Lai, C., Wang, Q., Li, X., & Hu, X. (2016). The influence

of individual espoused cultural values on self-directed

use of technology for language learning beyond the

classroom. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 676–

688.

Lee, S. G., Trimi, S., & Kim, C. (2013). The impact of

cultural differences on technology adoption. Journal of

World Business, 48(1), 20–29.

Leidner, & Kayworth. (2006). Review: A Review of

Culture in Information Systems Research: Toward a

Theory of Information Technology Culture Conflict.

MIS Quarterly, 30(2), 357.

Lu, J., Yu, C., Liu, C., & Wei, J. (2017). Comparison of

mobile shopping continuance intention between China

and USA from an espoused cultural perspective.

Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 130–146.

Martins, C., Oliveira, T., & Popovič, A. (2014).

Understanding the Internet banking adoption: A unified

theory of acceptance and use of technology and

perceived risk application. International Journal of

Information Management, 34(1), 1–13.

Masimba, F., Appiah, M., & Zuva, T. (2019). A Review of

Cultural Influence on Technology Acceptance. 2019

International Multidisciplinary Information

Technology and Engineering Conference (IMITEC).

Momani, A., & Jamous, M. (2017). The Evolution of

Technology Acceptance Theories. International

Journal of Contemporary Computer Research (IJCCR),

1(1), 51–58.

Ng, S. I., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. (2007). Are Hofstede’s

and Schwartz’s value frameworks congruent?

International Marketing Review, 24(2), 164–180.

Özbilen, P. (2017). The Impact of Natural Culture on New

Technology Adoption by Firms: A Country Level

Analysis. International Journal of Innovation,

Management and Technology, 8(4), 299–305.

Pancar, T., & Ozkan Yildirim, S. (2021). Exploring factors

affecting consumers’ adoption of wearable devices to

track health data. Universal Access in the Information

Society.

Petersen, F., Brown, A., Pather, S., & Tucker, W. D. (2019).

Challenges for the adoption of ICT for diabetes self‐

management in South Africa. The Electronic Journal of

Information Systems in Developing Countries, 86(5),

1–14.

Srite, & Karahanna. (2006). The Role of Espoused National

Cultural Values in Technology Acceptance. MIS

Quarterly, 30(3), 679.

Sriwindono, H., & Yahya, S. (2012). Toward Modeling the

Effects of Cultural Dimension on ICT Acceptance in

Indonesia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

,

65(ICIBSoS), 833–838.

Sriwindono, H., & Yahya, S. (2014). The Influence of

Cultural Dimension on ICT Acceptance in Indonesia

Higher Learning Institution. Australian Journal of

Basic and Applied Sciences, 8(5), 215–225.

Straub, D., Keil, M., & Brenner, W. (1997). Testing the

technology acceptance model across cultures: A three

country study. Information & Management, 33(1), 1–

11.

Su, Z., & Sauers, D. A. (2009). The applicability of widely

employed frameworks in cross-cultural management.

Journal of Academic Research in Economics, 1–24.

Sun, S., Lee, P., & Law, R. (2019). Impact of cultural values

on technology acceptance and technology readiness.

International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77,

89–96.

Sun, Y., Wang, N., Guo, X., & Peng, Z. (2013).

Understanding the acceptance of mobile health

services: A comparison and integration of alternative

model. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research,

14(2), 183–201.

Swierad, E., Vartanian, L., & King, M. (2017). The

Influence of Ethnic and Mainstream Cultures on

African Americans’ Health Behaviors: A Qualitative

Study. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 49.

Tamilmani, K., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020).

Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information

Technology: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of UTAUT2.

Information Systems Frontiers, 1–19.

Tarhini, A., Hone, K., Liu, X., & Tarhini, T. (2017).

Examining the moderating effect of individual-level

cultural values on users’ acceptance of E-learning in

developing countries: a structural equation modeling of

an extended technology acceptance model. Interactive

Learning Environments, 25(3), 306–328.

Teo, T., & Huang, F. (2018). Investigating the influence of

individually espoused cultural values on teachers’

intentions to use educational technologies in Chinese

universities. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(5–

6), 813–829.

Trompenaars, A., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1997). Riding

the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural

Diversity in Global Business (2

nd

edition). Nicholas

Brealey.

Ung, S. K. (2017). Role of Cultural and Psychological

Factors Influencing Diabetes Treatment Adherence.

Loma Linda University.

Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu. (2012). Consumer Acceptance

and Use of Information Technology: Extending the

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology.

MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157.

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F., & Morris, M. (2007). Dead Or

Alive? The Development, Trajectory And Future Of

Technology Adoption Research. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 8(4), 267–286.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D.

(2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology:

Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–

478.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2016). Unified

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A

Synthesis and the Road Ahead. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 17(5), 328–376.

Waki, K., Fujita, H., Uchimura, Y., Omae, K., Aramaki, E.,

Kato, S., Lee, H., Kobayashi, H., Kadowaki, T., & Ohe,

K. (2014). DialBetics. Journal of Diabetes Science and

Technology, 8(2), 209–215.

Yavwa, Y., & Twinomurinzi, H. (2018). Impact of Culture

on E-Government Adoption Using UTAUT: A Case Of

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

48

Zambia. 2018 International Conference on

EDemocracy & EGovernment (ICEDEG), April, 356–

360.

Yuan, S., Ma, W., Kanthawala, S., & Peng, W. (2015).

Keep Using My Health Apps: Discover Users’

Perception of Health and Fitness Apps with the

UTAUT2 Model. Telemedicine and E-Health, 21(9),

735–741.

Zhang, Y., Weng, Q., & Zhu, N. (2018). The relationships

between electronic banking adoption and its

antecedents: A meta-analytic study of the role of

national culture. International Journal of Information

Management, 40, 76–87.

Zhao, J., Freeman, B., & Li, M. (2016). Can mobile phone

apps influence people’s health behavior change? An

evidence review. Journal of Medical Internet Research,

18(11).

APPENDIX

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in relation to diabetes

self-care behaviours

Power

distance

If a DM patient subscribes to a power

distance culture, they may only trust their

doctors or prefer visiting a doctor. The

patient would prefer professional

assistance and advice from a health care

professional rather than using an m-

health a

pp

lication.

Individualism

-collectivism

If a DM patient forms part of an

individualistic society, they will make

their own informed decision as to how to

manage their condition.

If a DM patient who forms part of

collectivistic culture, they will make

health-related decisions based on the

values and beliefs of their societ

y

Masculinity-

femininity

If a DM patient subscribes to a masculine

society, the individual may not self-

manage their condition effectively as

working is a means of survival and

success.

If a DM patient subscribes to a femininity

culture, they will be viewed as nurturers

who care for others. These patients will

make informed health decisions to assist

others in leading healthier lifestyles. This

suggests that they cannot manage their

condition as they must see to the needs of

others.

Uncertainty

avoidance

If a DM patient subscribes to an

uncertainty avoidance society, the

patient may find it difficult to self-

manage their diabetes due to factors such

as crime and the fear of makin

g

an error

which could result in someone obtaining

their

p

ersonal information.

Long-term

orientation-

short-term

orientation

If a DM patient subscribes to a long- term

orientation culture, they will plan their

diabetes self-care activities to ensure

enough finances are available to

maintain their condition.

If a DM patient subscribes to a short-

term orientation culture, the patient will

follow the traditions of their society in

terms of managing their condition.

Indulgence-

Restraint

If a DM patient subscribes to an

indulgence society, they will make

health-related decisions that are

satisfactory to them to ensure that they

are happy.

If a DM patient subscribes to a restraint

culture, they will not take the initiative to

make their own health-related decision

as rules are essential in following a

diabetes self- mana

g

ement re

g

ime.

Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner cultural model in

relation to diabetes self-care behaviour activities

Individualism

versus

Communitari

anism

if a DM patient subscribes to an

“Individualistic culture”, the patient

might be inclined to seek out solutions in

relation to making their own informed

decision and take care of themselves

Universalism

versus

Particularism

If DM patients subscribe to a

“Universalism culture”, the individual

may make diabetes self-care decisions

b

ased on their values and

b

eliefs.

Specific

versus Diffuse

If a DM patient subscribes to a “Specific

culture”, they may share their thoughts

and feelings about their diabetes self-

care activities and decision-making with

others

Affectivity

versus

Neutrality

if a DM patient subscribes to an

“Affective culture”, the patient may

express and share their emotions and

feelings to their doctors about their

diabetes self-care activities

Internal

direction

versus

External

direction

People who form part of an internal

direction culture believe they can control

their environment to achieve their goals.

Achieved

Status versus

Ascribed

Status

If a DM patient subscribes to an ascribed

status, their demographics (race, age and

gender) may influence their diabetes

self-mana

g

ement decision.

Sequential

Time versus

Synchronic

Time

People who form part of a sequential

culture may prefer to have a detailed

agenda of activities and would perform

one activit

y

at a time.

The Role of Culture in User Adoption of Mobile Applications for Self-management of Health: A Conceptual Framework

49