Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL

Technology

Caterina Maidhof

a

, Martina Ziefle

b

and Julia Offermann

c

Chair of Communication Science, Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57,

Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Perception of Privacy, Older Adults, AAL Technology, Lifelogging, Mental Models, Cognitive Maps, 3CM

Method.

Abstract: Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) technologies have a high potential to combat healthcare challenges while

supporting older adults to live independently at their own home. Despite the general positive uptake of such

technology, perceptions of barriers of acceptance persist, a major one regards privacy. With an explorative

qualitative approach, the current study aimed at investigating participants` cognitive representations of a

scenario in which AAL is installed in the own home as a support at an older age. Special focus was on eliciting

participants` implications for privacy in this scenario and to understand the individual requirements of using

AAL technology at home. Opinions of 12 participants (age range: 23-81 years) from Germany and

Switzerland were assessed through semi-structured interviews. The paper presents descriptive results and

emerging themes of the mapping approach. The results show the usefulness of the method to understand

thought processes of potential users regarding privacy preferences and technology usage. Findings might be

useful to inform technical designers as well as lawmakers to consider these usage requirements during

technology or law development.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) technologies are

intended to be a constant part of the day-to-day life of

older adults in need of care (Blackman et al., 2016;

Muñoz et al., 2011). Such technological solutions

have a high potential to effectively combat healthcare

challenges and support people living at home in older

age (Peek et al., 2014) – improving quality of life for

them as well as their caregivers (Pollack, 2005).

Various sensors, actuators, smart interfaces, and

artificial intelligence are integrated into homes and

lives of the elderly to provide support for functional

capabilities of “activities of daily living” as well as

sensing and preventing risky situations such as falls

(Blackman et al., 2016; Calvaresi et al., 2017). In the

context of AAL, many sensors, either wearable or

ambient installed, are used for lifelogging. The latter

term refers to digitally tracking and documenting

everyday live by recording physiological and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0573-4498

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6105-4729

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1870-2775

behavioural data in real time which is stored for a

subsequent knowledge extraction (Selke, 2016). To

adequately log people`s lives, data recording is

always on and usually shared with stakeholders such

as care personnel or medical practitioners to

adequately design independent-living strategies

(Selke, 2016).

1.1 AAL Technologies, Acceptance and

Privacy

Generally, many of these specific applications are

perceived positively by a broad range of users and are

thought to be helpful and beneficial, providing an

increased feeling of safety and greater independence

(e.g., Garg et al., 2014; Gövercin et al., 2016;

Lorenzen-Huber et al., 2011; Wild et al., 2008).

Potential barriers and concerns raised by different

user groups are the lack of personal contact, perceived

control, continuous monitoring, fear of data misuse as

well as invasion of privacy (e.g., Beringer et al., 2011;

Maidhof, C., Ziefle, M. and Offermann, J.

Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0011046200003188

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2022), pages 93-104

ISBN: 978-989-758-566-1; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

93

Demiris et al., 2004; Kirchbuchner et al., 2015; van

Heek et al., 2018). An increased need for care

(Offermann-van Heek et al., 2019; van Heek et al.,

2017) as well as care experience can have an

influence on technology acceptance. Care

experienced people seem to rely more on emotional

aspects compared to inexperienced potential users

(Offermann-van Heek & Ziefle, 2019). General

findings from Offermann-van Heek and Ziefle

(2019) suggest that data access and privacy are the

most relevant factors when deciding on AAL

technology usage for both, caretakers and caregivers.

Indeed, privacy concerns are a main barrier to

acceptance of AAL (Peek et al., 2014; Yusif et al.,

2016) and they largely come about when the actual

level of privacy does not match the desired amount

(Altman, 1976). The “ideal” amount of privacy and

the balance between sharing and protecting individual

data mainly depend on the context and personal

attitudes (Altman, 1976; Bergström, 2015;

Nissenbaum, 2010). This reflects findings that

privacy concerns in the context of AAL are tradeable

in adequate circumstances. Ulrich et al. (2020) show

that older adults are willing to trade privacy for safety

due to their need for autonomy, suggesting that users`

willingness to reduce privacy is altered especially

when they feel in control of the situation. Similarly,

privacy concerns are reduced if the devices provide

positive contributions to health and wellbeing, are

easy to use, and do not cause stigmatization (Ulrich et

al., 2020). Findings from a longitudinal study of

Himmel and Ziefle (2016) reveal that technology

acceptance depends on the location of the devices in

the user´s home. Technology in more private rooms

such as the bath and bedroom are less accepted

compared to the kitchen, living room or the home

office.

Taking the previously reviewed literature into

account it becomes evident that privacy is a

multidimensional construct and its evaluation in the

AAL context of whether it is a concern, a desired

state, or even a tradeable unit depends on multiple

contextual as well as personal factors. Based on

previous definitions of privacy Burgoon (1982)

makes a distinction of four dimensions of privacy that

account for the complex circumstances in the context

of AAL (Schomakers & Ziefle, 2019). Namely, in the

AAL context dimensions of social privacy (control

over social contacts, interaction, and

communication), of physical privacy (degree of

physical inaccessibility) as well as of psychological

privacy (degree of inaccessibility to thoughts,

feelings, and intimate information), and of

informational privacy (control over personal

information) might play a pivotal role.

One way to study the multifaced construct of

privacy is through the assessment of mental models.

This has already been done, for instance, to assess

laypersons general conceptualization of privacy

(Oates et al., 2018), older adults` understanding of

privacy in digital and non-digital contexts (Ray et al.,

2019, 2021) as well as older adults` privacy

expectations in adaptive assistive technologies

(Hamidi et al., 2020).

In the context of ageing and living with AAL,

however, mental conceptualizations of privacy still

require further investigations.

1.2 Mental Representations of Privacy

and Cognitive Maps

Mental models are cognitive representations of the

external reality that guide people to interact with the

world around them (Craik, 1943; Johnson-Laird,

1983). Based on personal life experiences,

perceptions, and understandings of the world

individuals create a cognitive structure that shapes the

basis of reasoning and decision making. Cognitive

maps have an influence on what information

individuals focus on and how they perceive it, thus,

ascribing them a leading role when it comes to

integrating and interpreting new information (Kaplan

& Kaplan, 1982). According to Collins and Gentner,

(1987) to explain unfamiliar domains people make

use of familiar mental models similar to the unknown.

As studies show (e.g., Rickheit & Sichelschmidt,

1999), phenomena that are not directly perceivable in

the external reality are explained in the same way as

unfamiliar domains. Kaplan and Kaplan (1981) view

cognitive maps as mental models that are schematics

of individuals’ cognitive representation of a specific

situation or problem. Kearny and Kaplan (1997)

argue that the most important, significant, and

concerning contents of a cognitive map are those

quickly coming to mind.

Even though, to date there is no consensus on the

definition of a mental model (e.g., see Thagard, 2010)

and still confusion about the nature of cognitive maps

(e.g., see Kitchin, 1994), various methods exist to

elicit and study people´s internal cognitive

representations of the world. Among the latter, there

is the open-ended 3CM (conceptual content cognitive

map) method, a corroborated method proposed by

Kearney and Kaplan (1997) for assessing peoples`

cognitive structures and processes. It has already been

used in the field of healthcare to understand personal

perceptions and concerns of people diagnosed with

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

94

lung cancer (Lehto & Therrien, 2010) and to

understand nurses` perceptions of children’s pain

(Van Hulle Vincent, 2007). The method is suited to

measure people`s viewpoints on complex domains

(Kearney & Kaplan, 1997) and as such, the

interaction and support with AAL technologies can be

seen. Particularly suited for small-scale samples and

for in depth-exploration the open-ended version of the

method will be employed in this study to gain

information about individuals’ perspectives of a

personal healthcare scenario with assistive

technology.

Besides exploratively testing through semi-

structured interviews the effectiveness of the

described method within the given AAL and care

context, the aim of the study is to deeply understand

thought processes regarding the role of personal

privacy while being supported and cared for by AAL

technology in older age. The goal is to get insights on

opinions of a diverse sample consisting of people

from two different European countries, being of all

ages, with and without (professional) care experience

and various levels of technical understandings. In line

with previous theoretical explanations and given a

scenario where people are confronted with using

AAL technology in their own home for the first time,

they would immediately think of and possibly reveal

core contents of their existing mental representation

regarding this scenario.

2 METHOD AND MATERIALS

This chapter outlines the empirical approach of the

study. First, the characteristics of the semi-structured

interviews and its successive data analysis are

explained. Subsequently, the interview guidelines

and procedure are described in detail including the

AAL scenario. Lastly, participants of the study are

presented.

2.1 Semi-structured Interviews and

Data Analysis

The interview was divided into two main parts. The

first part consisted of questions regarding privacy in

daily life and feelings of privacy violation. The

second part started with the introduction of the AAL

scenario. Based on the Conceptual Content Cognitive

Map (3CM) method described by Kearney and

Kaplan (1997) participants were guided to create their

mental representation of this scenario.

The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed

verbatim. The theoretical foundation of the analysis

was the thematic qualitative text analysis as outlined

by Kuckartz (2014). The study was carried out in both

German and Italian. The selected quotes were

translated into English for this publication.

2.2 The Interview Procedure

Participants were welcomed to the interview with a

general introduction into the topic of privacy and

AAL technologies.

The first part of the interview consisted of four

main questions regarding the meaning of privacy,

privacy behaviour, and feelings of privacy violation.

The second part of the interview started with the

introduction into the AAL scenario and was followed

by the task of creating a mental map. Therefore,

participants were asked to imagine themselves in this

scenario and were told that their answers of the

upcoming three questions were written down in boxes

to create a visualization of their thoughts – each box

corresponded to another mental object in this

scenario. These three questions addressed

participants` first impression of the scenario,

connections they could draw to privacy and their ideal

imagination of this technology in line with their

privacy preferences. Each topic was discussed

extensively and only when participants clearly

signalled that the visualization map was complete for

them, the interviewer proceeded. Like this, maps

varied in complexity meaning that the number of

objects within the maps varied depending on

participants` personal understanding of the scenario.

As for the subsequent task participants were asked to

sort the answer boxes into meaningful groups of

statements. Then, participants had to code each group

or box according to the degree of importance, i.e.,

how important they would consider each of their

statements in terms of privacy in this scenario. The

interviewer then picked the statement that was rated

as most important and questioned if it was

interchangeable. If so, participants were encouraged

to name what they considered as an adequate

exchange.

The interview finished with an informal talk about

participants` demographics and their experiences in

care as well as regarding technology.

2.2.1 The AAL Scenario

Participants were encouraged to picture themselves as

an eighty-year-old healthy but frail person living

alone at their own home. Participants had to imagine

that AAL technology was installed in their homes to

support them and to counteract frailty due to ageing.

Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL Technology

95

The type and functionality of this technology was not

important, but participants were informed that the

technology would have various social and functional

features. Among the latter the following were

mentioned: medical care support (e.g., measuring

temperature, blood pressure), household assistance

(e.g., turning light on and off, vacuum cleaning),

monitoring (e.g., gait monitoring), memory aid (e.g.,

daily reminders for medicine or important events) and

a social companion (e.g., motivates and provides

games for physical and cognitive exercise, facilitates

communication with family and friends). Hence, this

technology consisted of a very extensive non-human

support for both, the person in need of assistance as

well as the caregivers involved.

2.3 Participants

The qualitative interview study was carried out in

June and July 2021 with twelve participants who were

interviewed with semi-standardized questions

through videophone. The interviews lasted

approximately one hour and were conducted with

participants from Germany and from Switzerland

(Swiss-Italian region) who were recruited from the

personal network of the authors and volunteered to

take part in the study. The aim was to cover young,

middle-aged, and senior females and males differing

in their level of technical understanding and their care

experiences.

The interviews (N=12 participants, ranging in age

between 23 and 82 years M=52.67; SD=22.49) were

conducted and analysed. Half of them were females

(50% males). Nationality was not divided as equal as

gender, with interviewing five Swiss, all of them

Italian native speakers and seven Germans, all of

them German native speakers. As their highest

educational level, seven out of all participants stated

to hold an academic degree, among them one

participant holding a doctorate, whereas four

completed vocational training and one person holding

an A-level certificate. Slightly more than half of

participants (i.e., seven participants) stated having

(professional or informal) care experience, three

among them reported working in the medical or care

sector. High levels of technical literacy were

attributed to four participants whereas three were

classified as having low technical literacy. The

remaining five participants ranged in between. No

participant reported hands-on experience and

knowledge of AAL technologies.

All participants agreed to take part in this

empirical study after they were transparently

informed about the use of the collected data as well

as the purpose and aim of this qualitative research. No

compensation was given for participation.

4 RESULTS

In the following, results of the second part of the

interviews will be reported. Findings from this part

might be most relevant in understanding how people

conceptualize privacy in an AAL scenario.

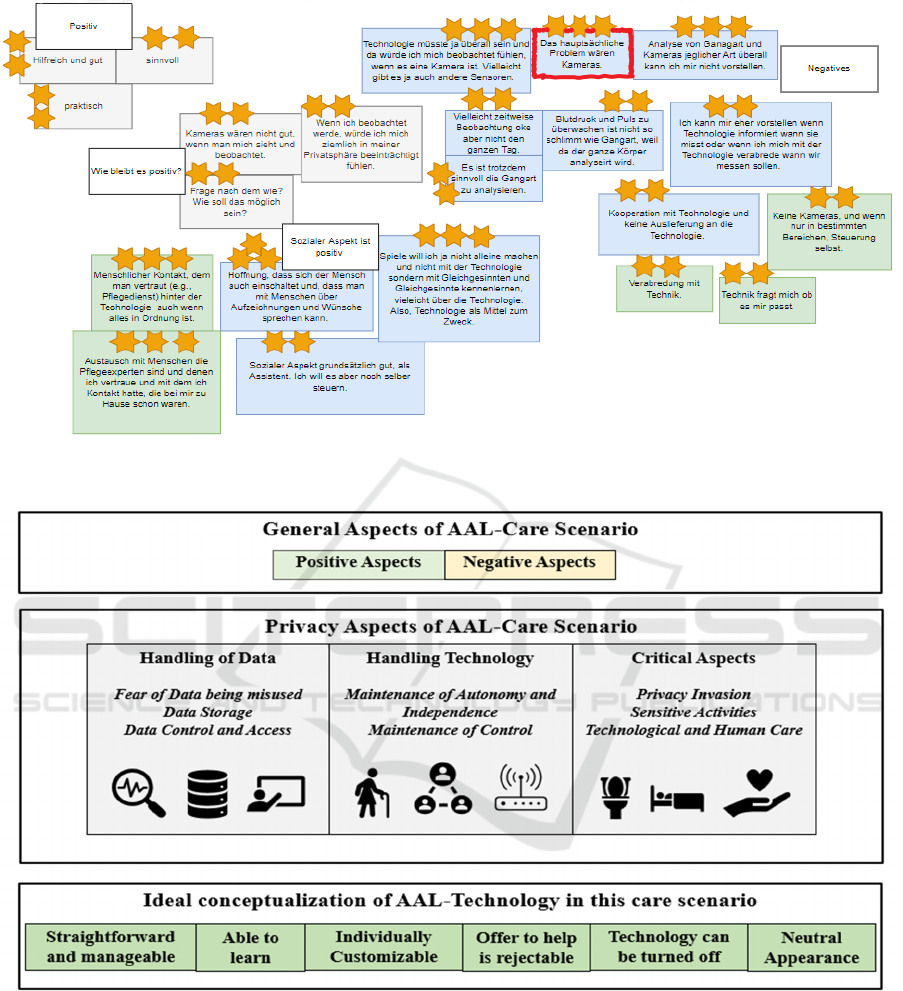

4.1 Descriptive Results

In total, maps of eleven participants were examined

(P2-P12). While every mental map was equally

informative the maps differed in complexity, i.e., the

number of objects included in the map (see Table 1).

Interestingly, P3 the most care experienced

participant (59 years, MA. Nursing and health

sciences, 22 objects) conceptualized the most

complex map with the highest number of objects

included (Figure 1) followed by the youngest,

technically highly skilled participant (23 years, 21

objects). Among the participants who created the

least complex map were the two oldest participants

(both aged 81, low-medium technical literacy, P12

informal care experience, both 7 objects). Participants

with more complex maps (P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P9,

P10) were able to group their objects into two to six

categories, whereas this was not possible for the less

complex maps of P7, P8, P11, and P12.

Seven participants were able to select one most

important object of the map. Among these chosen

objects were

“Safety” (P2), “The problem of camera

technology”

(P3) “Data Protection” (P5), “unobtrusive

technology”

(P6), “Independence” (P7), “Usefulness”

(P8), and

“Simple Use” (P9). The most important

object of the map was interchangeable, except for two

participants (P5, P8). Participants wished to replace

their most important object with

“increased quality of

life” (P2), “social contacts” (P3), “even more helpful

technology”

(P6), “being cared for by skilled and nice

professional caregivers”

(P7), and “being cared for by the

own two children”

(P9).

Table 1: Descriptive statistics regarding the number of

objects within the maps.

Descri

p

tive Statistics Partici

p

ants

Mean 14,36

Median 12

Mode (bimodal) 7 P7, P11, P12

Mode (bimodal) 12 P8, P9, P10

Max 22 P3

Min 7 P7, P11, P12

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

96

Figure 1: Exemplary schematic visualization of P3`s mental map (in German language). The yellow stars represent the coding

for importance (3 stars = very important). The box framed in red corresponds to the most important object.

Figure 2: Illustration of categories.

4.2 Qualitative Findings

Results from the thematic analysis of the single maps

revealed three major categories, “General Aspects of

the AAL Scenario”, “Privacy Aspects of the AAL

Scenario” and “Ideal Conceptualization of AAL

Technology”.

These three broad classifications were further

divided into several major and minor subcategories.

Allocations are illustrated in Figure 2 and details are

described in the following.

4.2.1 General Aspects of the AAL Scenario

Positive Aspects. Overall, participants mentioned

more general positive than negative thoughts on the

AAL scenario. Indeed, all participants but one (P4)

Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL Technology

97

had a positive first impression, meaning that the first

word they mentioned had a positive connotation.

In general, the AAL technology in this scenario was

considered as

“helpful for oneself” (P3) and “for

relatives”

(P4) as well as “useful” (P8) and “important

for life” (P12).

In addition, some participants even shared more

excitement when asked about their general

impression:

“For me it is fascinating if I fall down, and the system

calls an emergency service.” (P5)

“I am enthusiastic, […] it lights my thoughts. Without

the technology no one knows about my health, and I can

only guess if I am not well. Just thinking that with this

technology there is someone, is a great relief.”

(P10)

Negative Aspects. As what can be identified as

general negative aspects or concerns regarding the

AAL technology, only a few were mentioned.

Participants feared that interaction with AAL devices

would make them particularly aware of their frailty or

in the extreme case be the cause of further health

decline and frailness.

“Every day you are reminded of your frailty, you are

always reminded that you can´t do certain things

anymore and you have the feeling that you are

dependent on this thing. […].”

(P2)

“I am afraid that I am no longer challenged. Basically,

it is like diminishing self-esteem from the outside”

(P4)

4.2.2 Privacy Aspects of the AAL Scenario

Handling of Data. Participants frequently raised the

issue how data is handled in this scenario and

discussed it in various lights. Thoughts concerning

this topic can be divided into three subcategories that

are Fear of Data being misused, Data Storage and

Data Control and Access.

Fear of Data being misused. Participants were

aware that the AAL technology records most of their

everyday activities and health information which

makes the resulting data highly sensitive. Participants

feared fatal consequences if this data would get in

wrong hands.

“A film is a data, a photo is a data, a state of health can

also be another piece of information and I wouldn´t

want many others to know that I have a certain illness.

I mean inappropriate dissemination of data. You have

to understand who is on the other side, […] if one looks

for a specific purpose regarding health okey, but if one

looks to make fun of me then it becomes almost a

crime.” (P10)

Data Storage. How data is stored was only a

matter for participants with high technical

understanding. Indeed, to express preferences, one

might need to know how and where data can be stored

as well as what implication the storage location has

for data security. P5 for instance preferred data to be

stored locally rather than in a cloud.

Data Control and Access. Participants agreed that

the fewer people have access and control of the data,

the better. However, some preferred giving access to

a small circle of trusted people others favoured a care

service. Participants shared the reasons for these

preferences. P6 argued for granting access to a small

circle and gives an example of an

“uptight granny” who

does not want to show the data to anyone even though

it might be helpful. Therefore, she says, that it is

nonetheless important that a small circle of trusted

people has access to the real data because otherwise–

as she put it,

“you might end up cheating yourself.” (P6).

Others, such as P7, would prefer to give access mostly

to a care service to avoid being a burden for family

members and informal caregivers.

“Regarding data access and monitoring, I think it

should be a care service. If something extreme happens,

relatives can always be taken on board. [...] Smaller

issues might arise frequently, and a care service reacts

quickly and maybe comes over. I don´t want the

relatives to worry a lot and then be obliged to keep

checking.” (P7)

Handling Technology. Participants pictured ways

they would interact with such integrated AAL

devices. They discussed to what extent the degree of

autonomy and independence changes and potentially

diminishes in such a scenario. In addition, they

explored latitudes and limits of technology in terms

of keeping or giving up control over oneself. These

thoughts can be summarized into two categories,

namely Maintenance of Autonomy and

Independence and Maintenance of Control.

Maintenance of Autonomy and Independence.

As a first impression, participants felt that such AAL

technology would take away a lot of independence

and control from them and would not consider their

remaining cognitive and physical abilities required in

daily life. One participant having this opinion (P8)

stated that decisions on giving up autonomy and

independence highly depend on,

“the will to extend my

life” (P8) considering beliefs and values on life and

destiny one has at that point in time. Others

concentrated on the meaning of independence and

autonomy discovering that there might be two sides

of the same coin.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

98

“On one hand something is taken over but then you

keep your independence longer […]. On one hand

deactivated, on the other hand, increased autonomy. It

is perhaps a paradox” (P4)

“I would feel being taken care of as well as being

independent […] I don´t always need someone to come

by all the time but I can actually handle it myself and if

there is something wrong, the system takes care of it, so

I am coping with everyday life” (P2)

Maintenance of Control. Participants thoughts on

handling the technological devices were driven by the

fear of losing control over technology and with that

losing control over oneself. According to participants,

AAL technology should therefore operate based on

individual needs and avoid evoking feelings of being

controlled.

“Technology must serve me when I need it. The

machine must be at my service, and it is not I who must

be at the service of the machine.” (P10)

“When you are so old that you no longer know how to

operate this device you even feel more controlled by the

device. […]. Then, it would be important that the device

is hidden so that you don´t notice it or that the device

helps you to operate it to give you the feeling that it

doesn´t control you.” (P6)

The notion of control in this context was also

viewed as control over information about oneself and

with that control over the own image.

“Imagine if you say that you were doing well last week

and your friend replies: ´No I don´t believe you, I know

your data´. You decide what you tell your friend or how

you felt, and how you generally feel about yourself. You

decide what to tell and what don´t” (P6)

Critical Aspects. Three critical categories were

identified that can be put under the umbrella of

privacy in this AAL scenario. Namely, Privacy

Invasion, Sensitive Activities and Technological and

Human Care.

Privacy Invasion. During the process of creating

the mental map, participants gave concrete examples

regarding critical situations where privacy might be

threatened. Interestingly, some of the participants

considered this threat as rather unproblematic.

“It doesn´t bother me in my situation […] Maybe for the

younger ones it is a disturbance, but I don´t mind those

things, I go around and do things as I am and there is

nothing to hide -I have nothing to hide” (P12)

On the contrary, others mentioned situations

where interference of technology is not desired and

considered as a disturbance of privacy. Among them

P2 and P4 shared examples:

“An example: I am reading something, and I am

concentrating and now technology informs me it is my

turn to take my pills or whatever and I am disturbed. I

think that is an invasion of my privacy.” (P4)

“The more the measurement is noticeable […] thinking

of a moment when I have guests over who could also

see it, then I would feel that my privacy had been hurt.”

(P2)

Sensitive Activities. Activities that are repeatedly

cited as particularly sensitive and critical to monitor

are activities in the bath- and bedroom. In the

bathroom, especially toileting and showering were

concerning. Oftentimes, participants even either

rejected the use of technology in these intimate

moments or accepted it unwillingly.

“I would like it if there were areas without technology

for example in the bathroom or in the bedroom.” (P6)

“What I don´t feel comfortable with is, for example,

when I go to the toilet, knowing that I am being

watched, or other intimate acts that I don´t like to do in

public. […] As long as I understand this cognitively, I

can accept it, even if reluctantly. But I think it becomes

difficult when the mind can no longer grasp it. Then it

becomes a burden.” (P4)

Technological and Human Care. Despite all the

positive aspects mentioned about the AAL

technology in this scenario, participants talked about

their hope that human care and human contact is still

provided or at least complemented with technology.

“The technology is there but maybe one day a human

being will come by. That is what I hope. […] Even if

everything is okey every two days, once a week, you can

talk to a person about these things that were recorded

or about your wishes, that would be good. It doesn’t

matter if all the values are good, you still want to talk

to someone when you are alone” (P3)

“There is no longer a person who helps you and stays

with you all day long and therefore favours an

exchange of social information and physical contact

that a person who is alone may need. This is missing in

this scenario here.” (P8)

4.2.3 Ideal Conceptualization of AAL

Technology

Participants shared their ideal conception of the

technology in this scenario in line with privacy

preferences. This means that participants were asked

how they wanted the technology in this scenario

ideally to be designed in terms of functionalities,

Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL Technology

99

appearance, and interaction. Findings are

summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Ideal conceptualizations of AAL technology.

Ideal

Conceptualization

of Technology

Description

Straightforward and

manageable

Technology should be simple,

and it should be easy to learn

how to interact with it.

Able to learn Technology should have the

ability to learn about the users,

their habits, and (health)

conditions.

Individually

Customizable

Technology should adapt to the

user´s rhythm of life and each

function should be

customizable and work as the

user wishes.

Offer to help is

rejectable

Users should have the freedom

to refuse help from technology.

Technology can be

turned off

Users should be able to switch

the technolo

gy

off an

y

time.

Neutral Appearance Technology should be hardly

seen, be very subtle and discreet

or at least look like a design

object rather than a health

device.

5 DISCUSSION

The paper presented cognitive maps of potential users

of AAL technology and the resultant findings

regarding their opinions on living with such assistive

devices. This qualitative approach aimed at

understanding thought processes regarding privacy

when in need of care due to age-related frailness and

being supported by AAL technology.

5.1 General Findings and Privacy

Criteria

Overall, and in line with existing literature (e.g., see

Garg et al., 2014; Gövercin et al., 2016; Lorenzen-

Huber et al., 2011; Wild et al., 2008) participants had

a positive impression of themselves using AAL

technology at home in older age and mentioned more

positive than negative aspects.

Participants` opinions of the AAL scenario were

elicited with a cognitive mapping method (3CM).

Maps varied in complexity which is also reasonable

according to Kearney and Kaplan (1997) and maps of

experts tend to have stronger and more objects. In this

study, the sample consisted of non-experts of the

AAL domain, but several participants had

professional care experience and/or a high general

technical understanding. Participants with the least

complex maps were the two oldest participants (both

81 years) both with limited technical understanding

and no professional care experience. One explanation

might be that older adults generally have less

experience with technology compared to younger

adults and therefore have less developed mental

models of how to use them (Ziefle & Bay, 2004).

Opposed to that, the most care experienced,

technically skilled adult (59 years, MA. Nursing and

health sciences) created the most complex map. The

second most complex map was conceptualized by the

youngest technically highly skilled participant. Even

though both participants were not experts in the AAL

domain they had important knowledge in related and

relevant domains of care or technology respectively.

In line with theoretical argumentations (Collins &

Gentner, 1987; Rickheit & Sichelschmidt, 1999), this

knowledge has probably helped in the creation of

their compound mental maps. Previous findings have

already suggested that care experience plays a role in

AAL acceptance (Offermann-van Heek et al., 2019;

Offermann-van Heek & Ziefle, 2019). Related to this,

this study provides hints that care experiences are

strongly reflected in the mental model of an AAL

scenario which focuses on privacy implications.

Findings on privacy in this study can roughly be

allocated to Burgoon`s four dimensions of privacy

(Burgoon, 1982).

Naturally, the category Handling of Data

including its identified subcategories can be assigned

to the dimension of informational privacy (control

over personal information). Data contains intimate

details and therefore the dimension of psychological

privacy might also be relevant for this category.

Findings fit in the picture on AAL acceptance of

previous studies (e.g., Kirchbuchner et al., 2015;

Offermann-van Heek & Ziefle, 2019) confirming data

access and the fear of data misuse as relevant aspects.

The category Handling of Technology including

its subcategories regarding autonomy, independence,

and control might be most closely related to

psychological privacy (degree of inaccessibility to

thoughts, feelings, and intimate information) as well

as social privacy (control over social contacts,

interaction, and communication). Previous studies

show the importance of autonomy and independence

for older adults when interacting with technology

(e.g., Lorenzen-Huber et al., 2011; Ulrich et al.,

2020). Within the subcategory Maintenance of

Autonomy and Independence, several participants

concluded that AAL technology enhanced and

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

100

supported independence and autonomy even though

it invaded a large part of the intimate everyday life.

Previous studies have called it a trade-off between

autonomy and privacy (e.g., Lorenzen-Huber et al.,

2011). In this study, one participant labelled it as a

paradox which might be a less functional description

but it emphasizes the complexity and multificacety of

such an AAL scenario. Control and the feeling of

being in control when using AAL is another core

aspect when interacting with AAL (e.g., Schomakers

& Ziefle, 2019; Ulrich et al., 2020) and has been

summarized in this study in the subcategory

Maintainance of Control. Participants mentioned

their desire to keep control over their data as well as

to keep control over devices including being able to

reject technological offers and being able to turn

devices off completely, as results from ideal

conceptulaizations show.

The category Critical Aspects might somehow

be related to all privacy dimensions. The subcategory

Sensitive Activities might be particularly bounded to

the psychological as well as the physical dimension

of privacy. The latter because the sensitive activities

mentioned are typically done in the bath and bedroom

and some participants even referred to the location.

This is consistent with findings from Himmel and

Ziefle (2016). The importance to complement AAL

with human care and contact is emphasized in the

subcategory Technological and Human Care. The

fact that technology should not replace human care

has already been mentioned previously (e.g.,

Lorenzen-Huber et al., 2011). Indeed, participants

want actual humans to discuss their wellbeing and at

the same time participants consider human physical

contact as important contribution to their wellbeing.

The subcategory Privacy Invasion and several ideal

conceptualizations (i.e., “Able to learn”,

“Individually Customizable”) show that privacy

within an AAL scenario is a very personal matter.

Similarly, concerns especially regarding privacy are

best countered with customizable solutions and

individual support which partly includes human care.

5.2 Method Evaluation

The study procedure was based on the open-ended

3CM method. Participants quickly grasped the

cognitive mapping approach and provided objects to

be written on the cards in the form of entire sentences

or single words. The main constructs assessed were

“general perceptions of AAL in older age”, “privacy

perceptions when interacting with AAL” and “ideal

conceptualization of AAL”. According to Kearney

and Kaplan (1997), construct validity can be

examined by the following three major theoretical

expectations: (1) if participants are able to distinguish

between the objects they own and the ones they do

not (i.e., the extent to which participants are certain

that a specific object belongs in their mental

representation), (2) if hierarchical relationships are

shown through the creation of 5 ± 2 created

categories, and (3) if participants express satisfaction

with the measurement process.

These three criteria for construct validity apply to

most of the sample´s maps. Nonetheless, reliable and

quantifiable practices to test for these criteria during

data collection were limited. Firstly, concerning

ownership of the objects, no specific measures were

taken to test for it. However, participants` were given

time to think about further additions to the map

without being pressured. Without being prompted by

the interviewer, participants were also able to express

when their map was completed. Secondly, theoretical

expectations regarding hierarchical relationships

apply to six out of eleven maps. Indeed, six

participants were able to create minimum two and

maximum six categories and some participants even

provided headlines for each category. Lastly, most

participants expressed satisfaction and enthusiasm

during the mapping exercise. This was shown from

participants` persistent search for additional objects

and their positive comments on this mapping task

during the informal talk after the interview.

Overall, within the scope of available resources

and objectives of the study, reasonable efforts and

measures were taken to ensure construct validity as

best as possible. Furthermore, the high degree of

consistency with existing findings on privacy

perceptions and acceptance of AAL suggest that the

method is appropriate for the assessment of the given

context.

5.3 Practical Implications

The field of AAL connects many disciplines such as

legal, technological, and social disciplines, and

benefits from close inter- and transdisciplinary

collaboration and communication. As such the

reported findings from a social science perspective

might have implications for engineers and designers

as well as lawmakers working on aspects of AAL.

Especially when it comes to the perception of an

“Ideal” Conceptualization of Technology, the

insights of potential users of such AAL devices in

terms of expectations and requirements towards an

accepted technology in line with privacy preferences

might be informative for other disciplines and

Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL Technology

101

professional groups. From the results, several key

principles can be outlined:

Usability. AAL users want to feel in control of

technology, being able to turn it off and to manage it

easily, even with little technological knowledge. This

means, the usability of the AAL interface is key.

Interaction with the interface should be simple and

explainable in a few steps. If users know how to

navigate the device, their feeling of control will be

enhanced.

Framing and Information Style. Even though

AAL might support crucial tasks of daily life,

technological support should never be provided in an

authoritarian and domineering way. Ideally, users

should barely be aware of the technological support

they receive. This might be accomplished with

technological features that enable customization and

personalization of AAL devices. Acceptance and

integration of AAL in daily life becomes more natural

for users if devices can quickly adapt to personal

rhythms and preferences of each user. Preferences

can range from technological functioning, interaction

modality and data sharing to the actual design and

visibility of AAL.

AAL should Match Individual (Design)

Preferences at Home. Indeed, AAL does not only

need to fit to users` life rhythms but also to their own

home and the way users feel at home. The own four

walls are a place of refuge, creativity, and wellbeing

and not a healthcare facility. Despite its purpose of

care and health monitoring, AAL and particularly its

hardware should be designed to reflect standards of

home interior.

Perception of Control should Be Considered by

Legal Framing. Furthermore, this study bears

another implication especially regarding legal

aspects. Again, the notion of control plays a crucial

role. In fact, participants, as potential users, stated to

prefer being in control of technology but at the same

time, they emphasized the importance of being in

control of the data captured by the devices. They want

to know and decide with whom, how, and when data

is logged and shared. At the same time, potential data

misuse and hacking are a great concern. As users

might decide on data access and storage based on

their personal preferences, the legal framework

should enable a broad range of data elaboration

methods while ensuring rights of users and allow for

strict prosecuting in cases of misuse.

Those key features should be considered in future

professional education not only for care personnel but

also for technical designers and persons that are in

charge of providing legal frameworks. The more such

user aspects are considered from the very beginning

of technological development, the higher will be the

potential of acceptance of AAL technologies. This

especially applies to the type of technology under

study. In particular, camera technologies and sensors

as essential parts of AAL technology might be

important when it comes to perceptions of privacy.

Thus, based on current research (Wilkowska et al.,

2021), future studies should focus on the specificity

of privacy perceptions of visual technologies at home.

5.4 Limitations and Future Research

The applied qualitative procedure was an explorative

study to evaluate the methodological approach,

including the 3CM Method, and its suitability to

examine privacy perceptions within an AAL context.

It proofed useful in getting the participants to think

and reflect thoroughly about the given AAL scenario

and the implications for privacy. Nonetheless, the

validity of the method has limitations as outlined

previously.

Related to the representativeness of the method

might be the fact that the present qualitative

assessment was scenario-based and did not evaluate

actual technology and real-life experience and

knowledge of the given domain.

Furthermore, as the study was explorative, the

AAL scenario used for the creation of mental maps

was very generic. Indeed, the technology described

had many functions and left a lot of space to the

imaginary. To attain more elaborate cognitive maps

the technology presented should be more specific and

its functioning should be explained more explicitly.

Ideally, participants should have the opportunity to

test the actual technology for a determinate period

prior to the assessment of their mental representations

regarding it.

The semi-structured interviews all lasted roughly

one hour, and the mental mapping procedure was

created in the second half. The long duration might

have been challenging especially for older

participants who sometimes showed difficulties in

concentrating until the end of the interview. Future

studies attempting to study mental conceptualizations

might solely focus on the creation of the mental map

without any further questions.

The present study was conducted in two

neighbouring countries in Europe, namely Germany

and Switzerland (Italian-speaking region). No

remarkable differences between answers of

participants could be identified due to nationality. For

future studies, the approach of this study should be

applied in other non-European countries to compare

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

102

mental conceptualizations of privacy within AAL in

different cultures and certain healthcare systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors thank all participants for their enthusiasm,

patience, and openness to share their opinions during

the interview sessions. We also thank Sophia Otten

and Alexander Hick for research support. This work

resulted from the project VisuAAL “Privacy-Aware

and Acceptable Video-Based Technologies and

Services for Active and Assisted Living” and was

funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020

research and innovation programme under the Marie

Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 861091.

REFERENCES

Altman, I. (1976). Privacy A Conceptual Analysis.

Environment and Behavior, 8(1), 7–29.

Bergström, A. (2015). Online privacy concerns: A broad

approach to understanding the concerns of different

groups for different uses. Computers in Human

Behavior, 53, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.chb.2015.07.025

Beringer, R., Sixsmith, A., Campo, M., Brown, J., &

McCloskey, R. (2011). The “acceptance” of ambient

assisted living: developing an alternate methodology to

this limited research lens. Proceedings of the

International Conference on Smart Homes and Health

Telematics, Toward Useful Services for Elderly and

People With Disabilities., 161–167.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21535-3_21

Blackman, S., Matlo, C., Bobrovitskiy, C., Waldoch, A.,

Fang, M. L., Jackson, P., Mihailidis, A., Nygård, L.,

Astell, A., & Sixsmith, A. (2016). Ambient Assisted

Living Technologies for Aging Well: A Scoping

Review. Journal of Intelligent Systems, 25(1), 55–69.

https://doi.org/10.1515/jisys-2014-0136

Burgoon, J. K. (1982). Privacy and Communication. Annals

of the International Communication Association, 6(1),

206–249.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.1982.11678499

Calvaresi, D., Cesarini, D., Sernani, P., Marinoni, M.,

Dragoni, A. F., & Sturm, A. (2017). Exploring the

ambient assisted living domain: a systematic review.

Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized

Computing, 8(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s12652-016-0374-3

Collins, A., & Gentner, D. (1987). How people construct

mental models. In D. Holland & N. Quinn (Eds.),

Cultural models in language and thought. (pp. 243–

268). Cambridge University Press.

Craik, K. J. W. (1943). The nature of explanation.

Cambridge University Press.

Demiris, G., Rantz, M. J., Aud, M. A., Marek, K. D., Tyrer,

H. W., Skubic, M., & Hussam, A. A. (2004). Older

adults’ attitudes towards and perceptions of “smart

home” technologies: A pilot study. Medical Informatics

and the Internet in Medicine, 29(2), 87–94.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14639230410001684387

Garg, V., Camp, L. J., Lorenzen-Huber, L., Shankar, K., &

Connelly, K. (2014). Privacy concerns in assisted living

technologies. Annales Des Telecommunications/Annals

of Telecommunications, 69(1–2), 75–88.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12243-013-0397-0

Gövercin, M., Meyer, S., Schellenbach, M., Steinhagen-

Thiessen, E., Weiss, B., & Haesner, M. (2016).

SmartSenior@home: Acceptance of an integrated

ambient assisted living system. Results of a clinical

field trial in 35 households. Informatics for Health and

Social Care, 41(4), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.3109/

17538157.2015.1064425

Hamidi, F., Poneres, K., Massey, A., & Hurst, A. (2020).

Using a participatory activities toolkit to elicit privacy

expectations of adaptive assistive technologies.

Proceedings of the 17th International Web for All

Conference, W4A 2020, April. https://doi.org/10.1145/

3371300.3383336

Himmel, S., & Ziefle, M. (2016). Smart Home Medical

Technologies: Users’ Requirements for Conditional

Acceptance. I-Com, 15(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/

10.1515/icom-2016-0007

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983). Mental Models. Cambridge

University Press.

Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1982). Cognition and

Environment: Functioning in an uncertain world.

Ulrich Books.

Kearney, A. R., & Kaplan, S. (1997). Toward a

methodology for the measurement of knowledge

structures of ordinary people: The conceptual content

cognitive map (3CM). In Environment and Behavior

(Vol. 29, Issue 5, pp. 579–617).

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916597295001

Kirchbuchner, F., Grosse-Puppendahl, T., Hastall, M. R.,

Distler, M., & Kuijper, A. (2015). Ambient Intelligence

from Senior Citizens’ Perspectives: Understanding

Privacy Concerns, Technology Acceptance, and

Expectations. AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE, AMI 2015,

9425, 48–59.

Kitchin, R. M. (1994). Cognitive maps: What are they and

why study them? Journal of Environmental

Psychology, 14(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S027

2-4944(05)80194-X

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative Text Analysis A Guide to

Methods, Practice Using Software (K. Metzler (ed.)).

SAGE Publications.

Lehto, R., & Therrien, B. (2010). Death concerns among

individuals newly diagnosed with lung cancer. Death

Studies, 34(10), 931–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/

07481181003765477

Lorenzen-Huber, L., Boutain, M., Camp, L. J., Shankar, K.,

& Connelly, K. H. (2011). Privacy, Technology, and

Aging: A Proposed Framework. Ageing International,

Exploring Privacy: Mental Models of Potential Users of AAL Technology

103

36(2), 232–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-010-

9083-y

Muñoz, A., Augusto, J. C., Villa, A., & Botía, J. A. (2011).

Design and evaluation of an ambient assisted living

system based on an argumentative multi-agent system.

Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 15(4), 377–387.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-010-0361-1

Nissenbaum, H. (2010). Privacy in Context: Technology,

Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life. Stanford

University Press.

Oates, M., Ahmadullah, Y., Marsh, A., Swoopes, C.,

Zhang, S., Balebako, R., & Cranor, L. F. (2018).

Turtles, Locks, and Bathrooms: Understanding Mental

Models of Privacy Through Illustration. Proceedings

on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 2018(4), 5–32.

https://doi.org/10.1515/popets-2018-0029

Offermann-van Heek, J., Schomakers, E.-M., & Ziefle, M.

(2019). Bare necessities? How the need for care

modulates the acceptance of ambient assisted living

technologies. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

MEDICAL INFORMATICS, 127, 147–156.

Offermann-van Heek, J., & Ziefle, M. (2019). Nothing else

matters! Trade-offs between perceived benefits and

barriers of AAL technology usage. Frontiers in Public

Health, 7(JUN), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/

fpubh.2019.00134

Peek, S. T. M., Wouters, E. J. M., van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K.

G., Boeije, H. R., & Vrijhoef, H. J. M. (2014). Factors

influencing acceptance of technology for aging in

place: A systematic review. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 83(4), 235–248.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.01.004

Pollack, M. E. (2005). Intelligent technology for an aging

population: The use of AI to assist elders with cognitive

impairment. AI Magazine, 26(2), 9–9.

Ray, H., Wolf, F., Kuber, R., & Aviv, A. J. (2019). “Woe is

me:” Examining older adults’ perceptions of privacy.

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems -

Proceedings, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.33

12770

Ray, H., Wolf, F., Kuber, R., & Aviv, A. J. (2021). “Warn

Them” or “Just Block Them”?: Investigating Privacy

Concerns Among Older and Working Age Adults.

Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies,

2021(2), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.2478/popets-2021-

0016

Rickheit, G., & Sichelschmidt, L. (1999). Mental models:

some answers, some questions, some suggestions. In G.

Rickheit & C. Habel (Eds.), Mental models in discourse

processing and reasoning. (pp. 9–40). Elsevier.

Schomakers, E. M., & Ziefle, M. (2019). Privacy

perceptions in ambient assisted living. ICT4AWE 2019

- Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on

Information and Communication Technologies for

Ageing Well and e-Health, Ict4awe, 205–212.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0007719802050212

Selke, S. (2016).

Lifelogging: Digital self-tracking and

Lifelogging-between disruptive technology and cultural

transformation. (S. Selke (ed.)). Springer.

Thagard, P. (2010). How brains make mental models. In L.

Magnani, W. Carnielli, & C. Pizzi (Eds.), Model-based

reasoning in science and technology: Abduction, logic,

and computational discovery. Springer, Germany.

Ulrich, F., Ehrari, H., & Andersen, H. B. (2020). Concerns

and trade-offs in information technology acceptance:

the balance between the requirement for privacy and the

desire for safety. Communications of the Association

for Information Systems, 47, 227–247.

https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.04711

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., & Ziefle, M. (2018). Caregivers’

perspectives on ambient assisted living technologies in

professional care contexts. Proceedings of the 4th

International Conference on Information and

Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and E-

Health., 37–48. https://doi.org/10.5220/0006691400

370048

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., & Ziefle, M. (2017). Helpful but

spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems contrasting user

groups with focus on disabilities and care needs.

ICT4AWE 2017 - Proceedings of the 3rd International

Conference on Information and Communication

Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health, April, 78–

90. https://doi.org/10.5220/0006325400780090

Van Hulle Vincent, C. (2007). Nurses’ Perceptions of

Children’s Pain: A Pilot Study of Cognitive

Representations. Journal of Pain and Symptom

Management, 33(3), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.jpainsymman.2006.08.008

Wild, K., Boise, L., Lundell, J., & Foucek, A. (2008).

Unobtrusive in-home monitoring of cognitive and

physical health: Reactions and perceptions of older

adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27(2), 181–

200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464807311435

Wilkowska, W., Offermann-van Heek, J., Florez-Revuelta,

F., & Ziefle, M. (2021). Video Cameras for Lifelogging

at Home: Preferred Visualization Modes, Acceptance,

and Privacy Perceptions among German and Turkish

Participants. International Journal of Human-

Computer Interaction, 00(00), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2021.1888487

Yusif, S., Soar, J., & Hafeez-Baig, A. (2016). Older people,

assistive technologies, and the barriers to adoption: A

systematic review. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 94, 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ijmedinf.2016.07.004

Ziefle, M., & Bay, S. (2004). Mental models of a cellular

phone menu. Comparing older and younger novice

users. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including

Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and

Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 3160, 25–37.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-28637-0_3

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

104