Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative

Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology

Sophia Otten

a

and Martina Ziefle

b

Chair of Communication Science, Human-Computer Interaction Centre, RWTH Aachen University,

Campus-Boulevard 57, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Trust, Medical Care, AAL, Medical System.

Abstract: Due to a demographic change of the society, health care worker shortage and rising co- and multimorbidity

within older adults, constant care at home and at care facilities face a difficult task to combat these challenges.

Medical AAL technology offers many opportunities to relieve health care workers and assist older adults with

difficulties in managing activities of daily life (ADL). This study has adopted an exploratory interview

method to explore the users’ perceptions of trust in the medical context and specifically, related to medical

AAL technologies. Eleven participants ranging from 20 years to 87 years old (M = 52.27; SD = 24.2) were

interviewed and, in line with previous results in the literature, results revealed three categories of influences,

namely user factors, technology factors, and context factors. This implies a network of trust dependent on

various external and internal influences. These findings have practical implications for clinicians, developers,

policy makers and legal professionals.

1 INTRODUCTION

In Europe, the demographic change of the population

puts an increasing strain on the health care system. By

2070, it is estimated that 30% of Europeans are aged

65 years or older which is about 20% more than today

(see European Commission Report on the Impact of

Demographic Change). Due to these prognoses, it is

necessary to explore the possibilities of relieving the

medical system and bringing down the costs of health

care. Moreover, there is a shortage of health care

personnel which is predicted to increase dramatically

in the coming years with an estimated shortage of 4.1

million health care workers in 2030 (Michel &

Ecarnot, 2020). At the same time, older people also

have a desire to live on their own for as long as

possible (Peek et al., 2014). For example, the WHO

introduced a model of active ageing in order to

promote life satisfaction and quality of life (QoL) in

older adults (WHO, 2002). It defines active aging as

“[...] the process of optimizing opportunities for

health, participation and security in order to enhance

quality of life as people age.” (WHO, 2002). Given

the health barriers and comorbidities older people,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4027-5362

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6105-4729

especially in Western societies face, it is crucial to

connect theories of aging with the demands and

challenges of the health care system.

There are several approaches trying to tackle these

problems, one of them being active and assisted living

technologies (AAL technologies) designed to

enhance QoL and independence in older adults. These

solutions include wearable or ambient-installed

sensors, actuators, and smart interfaces that are

integrated into the homes of older adults. In this

context, most devices are used for lifelogging which

refers to the digital tracking and documentation of

behavioural and physiological data in order to extract

knowledge about a person’s health status and

behaviour (Climent-Perez et al., 2020; Steinke et al.,

2012). Given the challenges the health care system

faces at the moment and in the future, it is of

relevance to introduce and integrate these

technologies into the lives of older adults still living

at home but also to those living in care facilities.

Studies have shown that there are benefits but also

barriers of acceptance in the user population (Himmel

& Ziefle, 2016; Jaschinski & Allouch, 2015;

Wilkowska et al., 2021). The benefits seen by the

244

Otten, S. and Ziefle, M.

Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0011058300003188

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2022), pages 244-253

ISBN: 978-989-758-566-1; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

users are, among other, e.g., the medical security of

instant help, but also the independence of constant

care and comfort, the barriers mostly refer to privacy

and trust issues and data handling and management,

but also usability issues and the fear that technology

does not only assist but potentially replaces human

care (Ziefle & Calero Valdez, 2017; Schomakers et

al., 2021). Users tend to trade-off these benefits and

barriers in their overall evaluation of medical

technology which is why a user-centric view is

important for the implementation of AAL

technologies (Offermann-van Heek & Ziefle, 2019).

However, it is not only the perception of medical

technologies that influences the adoption of such but

also the context surrounding the devices, namely the

quality and the perceived reliability of the medical

system and medical personnel. Trust in the medical

system and health care workers is a core component

of how people perceive medical technology and thus

how open they are to using them in their homes.

There are several conceptualisations of trust in

general, the most common throughout literature being

trust as a belief and expectancy (McKnight &

Chervany, 2001). This study is based on the literature

on trust in medical and non-medical contexts and will

therefore adapt this construct. Trust is made up of

types that each measure a different aspect, i.e.,

dispositional trust (general trusting stance),

institutional or structural trust, and interpersonal trust

(trust in specific others) (McKnight et al., 2011;

Mayer et al., 1995). The combination of the keywords

“TRUST” and “ MEDICAL SYSTEM” on the

database “Web of Science” results in 10,847 hits up

until 2010 whereas up until 2021 there are as many as

53,319 hits on the subject, signalling the growing

interest in the role of trust in medical fields. Qiao et

al. (2015) found that participants’ trust in medical

technology depended on several other context-

dependent variables, such as trust in their primary

care physician and perception of how the physician

uses medical technology. This suggests a complex

network of moderating as well as predictive

relationships regarding trust in medical technology.

Within the broader context of technology, there

are three broad categories of variables that can be

outlined, namely technology factors, user factors, and

context factors (Xu et al., 2014; Bova et al., 2006). In

each category, there are further subgroups that focus

on specific aspects of and around the technology and

the users. While there are studies investigating all

kinds of technology, there is little information about

variables that are specific to the medical technology

context. In relation to that, there is no unified theory

of (the development of) trust across contexts. This

makes it crucial to investigate whether there are

contemporary influences on trust development and

how these fit into the broader concept of trust in the

medical field.

2 QUESTIONS ADDRESSED AND

STRUCTURE OF THE

INTERVIEW PROCEDURE

Based on the existing literature of trust in various

contexts, this study investigates the perceptions of

trust and trust development in a general and medical

context, as well as trust determinants in medical AAL

technology. Within the area of Ambient Assisted

Living (AAL), yet diverse holistic systems and

technical single-case solutions have been developed

in both academia and industry to enable staying at

home longer and independently (Memon et al., 2014;

de Ryter & Pelgrim, 2007, Ziefle, 2021). Still,

sustained adoption of these innovative technologies

in-home environments have failed (Wichert et al.,

2012). Beyond technical and economic reasons as

well as legal barriers towards data usage, one major

barrier could touch the missing trust of caretakers in

the medical technology applied in a very intimate and

sensitive usage context. This study therefore focuses

specifically on users’ trust in the medical context and

medical technology.

It employs a qualitative design with open-ended

questions and scenarios visualising AAL lifelogging

technology. The structure of the interview moves

from general, free association, to specific scenarios.

The first part dealt with perception of trust in general,

in the medical context, and regarding medical AAL

technology. The second part dealt with specific

examples of the medical system and from daily life,

as well as specific scenarios for the participants to

imagine and express their thoughts on trust

development in this context. The exact questions and

their order can be found in the Procedure section. This

was done to gain a first impression of trust

perceptions and only then to narrow in on particular

concerns of trust perceptions of AAL technologies.

Therefore, the first aim is to explore why and under

which conditions people trust the medical system.

The second aim is to explore how and under which

conditions people trust medical AAL technology.

The qualitative approach was chosen to gain

insight into ideographic perspectives of potential

users. Additionally, the exploratory method serves as

a first step into outlining trust perceptions in health

care contexts, i.e. the more specific questions were

Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology

245

based on previously researched variables across

different contexts to include possible influences that

were not associated with the medical context before.

The theoretical foundation of the questions was based

on previous factors outlined by several studies in the

literature, i.e. technology, user, and context factors.

The purpose of this paper was not to confirm those

previous results but questions were phrased in a way

that allowed participants to mention concerns related

to those factors. The reason of this context-

independent structure was to include other potential

influences and to not limit previous findings to the

medical context in order to avoid bias towards the

research aim. For the purpose of this paper, the quotes

were translated into English.

3 METHODS

3.1 Participants

The final dataset consists of eleven participants with

ages ranging from 20 years to 87 years old (M =

52.27; SD = 24.21). All interviews were conducted in

German as all participants were of German

nationality. The participants were recruited in the

social network of authors and volunteered to take part

in the study. In order to balance the diversity of

participants, they were selected based on gender, age,

and care experience (either professionally or

personally). There were six females and five male

participants. One participant holds a doctorate, nine

participants completed vocational training, and one

participant finished their A-levels. Three of them are

currently enrolled as students at German universities.

Two participants reported to work in the medical field

and four participants reported to have care

experience. Eight participants said to have medium

technical affinity, two participant said they have poor

technical affinity, and one participant said they have

superior technical affinity.

3.2 Open-ended Interviews and Data

Analysis

The interviews were conducted in Germany in

November 2021 with the online application Zoom.

The interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes and were

divided into a first part, addressing trust in general, in

the medical context, and regarding medical AAL

technology and a more context-related part, in which

specific examples of the medical system and from

daily life were discussed.

Participants answers were analysed using a

qualitative approach, comparing them to existing

factors in the literature. After having evaluated all

points, they were categorised according to previously

established groupings in the literature (Bova et al.,

2006; Xu et al., 2014; Qiao et al., 2015). The analysis

was done with MAXQDA 2018 (VERBI Software,

2019)

3.3 Procedure

At the start of the interview, the participants were

welcomed, received information about the study and

were asked to give informed consent as well as

permission to record the conversations which were

transcribed verbatim and after all interviews took

place. Firstly, they were asked about their perceptions

of trust in general, i.e. what they thought influences

trust and how they deal with trust and distrust in their

daily life. Secondly, they were asked about their

perceptions of trust in the medical context, i.e. what

made them trust in medical workers and institutions.

In the second part, the researcher explained properties

of AAL technologies, emphasising that participants

could picture the technology themselves, as long as

they had some features that are relevant for medical

lifelogging, such as recording vital signs and

detecting falls. Afterwards, the participants were

asked how their perceptions of trust change when

thinking about this type of medical technology and

how human medical care is different than

technological medical care. They were then asked to

rate several examples from their daily life and the

medical contexts according to their level of trust, e.g.

close relatives, medical care personnel, primary care

physician, and health insurance provider. Lastly, they

were presented with a scenario which employs one

form of AAL technology and differs in context-

dependant factors (i.e. living situation, type and

chronicity of disease, whether the scenario concerned

them or a relative, etc.) and asked about their worries

and thoughts on the scenario, and technological

advancements in the medical field altogether. In an

informal last part, they were asked about

demographic information, technological affinity, and

care experience.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Qualitative Findings

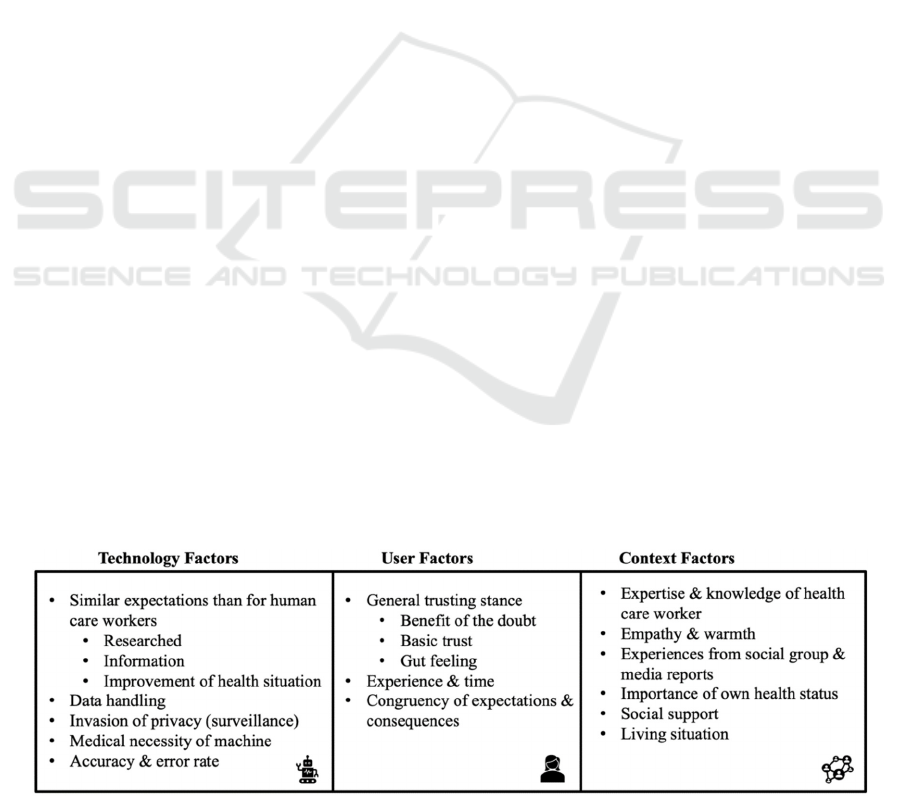

Results from the thematic analysis revealed three

major categories of trust predictors, namely user

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

246

factors, technology factors, and context factors. This

is close to the three categories outlined by previous

research and confirms established patterns of trust

development. An overview of the findings can be

found in Figure 1.

4.1.1 User Factors

Within this category, participants mentioned things

related to dispositions about trust and remarks about

general trusting stance. They mentioned phrases like

“basic trust” [P11] and “benefit of the doubt”[P6]

when referring to interactions with other people.

Moreover, they mentioned that a certain advance in

trust is needed in daily life, without which

interactions of any kind would not be possible. One

participant said that trust is the foundation for a

relationship because it creates intimacy between two

people.

“[without trust] there is a certain distance, I

think trust creates a huge amount of closeness

to a person or a group” [P1]

Overall, they each said that trust is crucial in day-

to-day interactions and depends on the person that the

interactions is with but most importantly, they also

said that trust develops over time and needs to be

fostered to be strengthened.

“trusting someone completely right at the

start, I’d be cautious with that. It develops

over time” [P7]

“a certain basic trust is there but evidently it

grows by doing things together” [P11]

“it depends on how long you’ve known a

person or generally if you know the person”

[P1]

When asked about what generally makes people

trust for the first time, participants often talked about

“intuition”[P5], “chemistry” [P8], and a “gut

feeling” [P8] which, when asked to elaborate, turned

out to be an emotional component that people either

felt they had or did not have. In addition to that,

behavioural components were also important to

participants’ trust feelings. This included experience,

caution, and observation on the trustor’s part but also

a congruency of saying and doing on the trustee’s

side. The participants felt like they needed to be able

to depend on what is being said and to know that the

other side was being honest and sincere with them

which is shown with their actions.

“that the person opposite of me is honest with

me and shares their thoughts and feelings with

me, or at least does not lie about them” [P3]

“that something I am expecting to happen also

comes true in that way” [P5]

“that I feel 100% safe and [...] that things are

not happening behind my back” [P6]

Lastly, the participants were asked about how

they deal with distrust and how they would act if

someone betrayed their trust. Seven participants said

that they would try to trust again but also mentioned

that if there was any doubt about the honesty of the

other person, they would withdraw from the

relationship. Moreover, they said that the other person

had to show their remorse and willingness to be

trusted again. Generally, they all mentioned that it

would take time and was not easy to rebuild and also

depended on the importance and secrecy of the topic.

The other four participants said that no matter how

much time passed and how the other person acted

after the betrayal, they would not fully trust that

person again and would keep their distance about

sharing information and spending time with them.

4.1.2 Technology Factors

In the interview, the participants were asked how their

trust in the medical context differed when thinking

about medical AAL technology. They mentioned

general opinions on medical AAL technology as well

as detailed requirements they would expect from such

devices.

General Aspects. Participants were generally

accepting and enthusiastic about the technology.

They mentioned mostly positive aspects about it and

could picture themselves using it. When questioned

about how trust in medical AAL technology differed

from general trust in the medical context, they said

that there was not much of a difference. More

precisely, they looked for the same qualities that they

also looked for in their physician or care personnel.

In relation to the technology, this included the topic

being researched (their physician being experienced,

having sound medical knowledge), having been

informed about what it does and where the data goes

(honesty and integrity of the physician), and an

improvement of their health situation (benevolence of

care personnel carrying out the medical care). Next to

the positive aspects, some participants also mentioned

concerns which are almost all related to the camera

based AAL technology and included the handling of

data, invasion of privacy, and whether the technology

is merely a way of companies trying to sell things that

are not absolutely necessary. Specifically, one

participant felt strongly that this type of technology

could not provide the kind of warmth, empathy, and

Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology

247

company that human care could provide and when

given the chance, she would not want it in her home.

“there is something missing and I just

wouldn’t want to use it [...]. Right now, I see it

with my mother because it’s the most beautiful

thing for her when someone stops by, talks to

her, holds her hand [...]. I just think that it is

very important for people, even if it’s just little

things. It’s something the machine can never

give, this kind of warmth.” [P7]

All in all though, they saw AAL technologies as a

possibility of enhancing medical care carried out by

humans and agreed about its benefits to relieve health

care workers, but none of them expect for one

participant could picture this solution as a

replacement of human care. In addition to that, almost

everyone said that they would prefer human care over

technological care, and would only use it if it was

medically indicated.

Specific Requirements. While some people

mentioned that they expected the technology to be

more precise than human medical care, they also said

that they wouldn’t want to rely on it completely. They

argued that because it does not have situational

factors like humans do, i.e. fatigue, traffic, human

error, the technology should work around the clock.

Moreover, one participant expected it to have a 100%

success rate because it should be tested to the point

where it does not make any errors anymore.

“if this technology failed and didn’t notice its

error, if it functioned 90% of the time but

everyone relied on it to work 100% of the time,

it would quickly become dangerous to the

person in need of care [...]. Right, that’s why

it needs to work 100% 24/7 for me to trust it.”

[P1]

“Well, if humans made an error I wouldn’t be

as pissed as if a machine made an error” [P5]

On the other hand, one participant said that as

long as it added to her overall medical care, she would

accept a certain error rate. This participant, however,

also said that she would check the accuracy of the

system beforehand as she herself works as an ICU

nurse.

“The more ‘false alarms’, the less people

react to it but someone will still come. Well, I

can still be sure that if I’m lying on the ground

and can’t call for help myself, that even if it’s

not in five minutes, somebody will come to

check on me in half an hour.” [P10]

Other participants felt like they could never

expect as much from a piece of technology than they

could from a health care worker. They felt like the

technology could be an addition but would always

have to be checked by a human. Across those

interviews, there was a discrepancy when these

participants were asked about the technology itself

and when asked to picture themselves in a scenario

where they would use it. In the scenario, they referred

to the human care as superior but when only asked

about the technology, they referred to it as being more

objective and accurate that human judgement.

4.1.3 Context Factors

After exploring general trust perceptions, participants

were asked about how trust manifested in the medical

context. Strikingly, all participants first spoke of

physicians when talking about medical trust. They

mentioned that, similar to general trust perceptions,

chemistry was a major component. Specifically, most

participants needed to feel that the physician had the

suited expertise and knowledge to treat them. In

relation to that, the outcome of previous patients was

also of importance. This was summarised as the

“word of mouth” [P1] in their social groups and in

media reports. On an emotional level, about half of

the participants wanted to “feel heard and listened

to” [P9] and that the physician paid attention to their

problems. This was summarised as empathy towards

the patient. The other half did not mention this as a

particularly important aspect, and one participant

thought it was not necessary for successful medical

treatment altogether.

Mostly participants that did not work in the

medical context felt that trust in the medical context

was more important than in other context as it

concerned their personal well-being and health.

Moreover, they said that there was no way for them

to verify the information given by the physician other

than seeing another medical professional.

“especially in the medical context [trust]

needs to be bigger because it is about your

own body and not about whether your kitchen

is even or your house is built well” [P1]

“it’s the same thing when the nurse says that

the medication is correctly prescribed and

given out but in reality someone messed it up,

then that’s something that influences trust, in

particular when it’s about body and soul”

[P3]

“without trust you wouldn’t want to place your

body in the hands of that person [physician]”

[P4]

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

248

Conversely, one participant who is a trained

physician mentioned that experience of the treating

physician was not only unimportant but was even a

negative aspect for her, as she felt that having treated

many patients was not predictive of competence and

most often associated with unjustified confidence.

“[Experience] is more of a negative factor,

actually, because I have experienced that

physicians who insist on having experience

usually don’t pay attention to details

anymore” [P5]

Taking these concerns together, it becomes

evident that most of the subsequent behaviour of

patients is related to how they perceive their treating

physician and care personnel. “Medical context” is a

term that all participants related to people, in

particular physicians. When asked about medical

technology, almost all of them connected it to the

conditions under which it would be introduced to

them, i.e. whether their physician appeared to

understand it themselves, whether it was covered by

their insurance, and whether they would receive

assistance in using it. Overall, it was clear that if they

trusted the medical personnel they were closest to,

they were more willing to try the technology as well.

However, if they felt disregarded and suspicious of

the intentions of health care workers, they would not

want to use the technology or risk having their data

be stored in medical files.

“as with the technology I’d say that that the

human is part of it, if the person explains to me

why this technology is useful and what it can

do, then I’d trust it for now” [P2]

“my first thought is that I wouldn’t trust the

care personnel that gets these alarms in the

end. [...] I’d trust the technology, yes, but I’d

question the people behind the system” [P4]

“the entire clinical staff should have

knowledge about this technology for me to

trust it” [P2]

These points suggest that the way of introducing

AAL technology is highly relevant for the acceptance

and willingness of potential users in this context.

However, there are other context factors that were

mentioned to be important as well. Participants felt

good about AAL technology, if it relieved the burden

on family members. They felt that they would most

likely try out the technology if they otherwise had to

rely on their family members to care for them. On the

other hand, they also felt more comfortable using the

technology if they lived alone and without social

support. The reasoning for this was that since they

had no one to help them with any of the tasks that are

provided in AAL technology, the technology would

be the assistance commonly expected of relatives.

“Especially when I imagine living alone, I

would probably perceive this as an extreme

relief” [P6]

Lastly, one participant also said that it depended

on his health status. He perceived it less of a choice

but more of a medical necessity, i.e. if he is healthy,

he wouldn’t try it as there is no need for it. However,

if he was sick and had to be cared for and there was

no medical personnel or family members to help, it

would be irrelevant as to whether he trusted the

technology because there would not be another

option.

“Even at the risk of this thing making

mistakes, because I myself couldn’t do it at all.

I would make mistakes in any case. [...] So, it

would always be worse without that

machine.“ [P3]

In line with part of this argument, more

participants mentioned that if they did have the ability

to manage without these systems, they would always

try to avoid having to use them. This suggests that

AAL technology is associated with a decline in health

status as they most often used examples of advanced

scenarios in disease management, e.g., having severe

dementia or being physically bed-bound.

Figure 1: Illustration of Categories.

Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology

249

5 DISCUSSION

This paper set out to investigate perceptions of trust

in a general and medical context, narrowing in on

trust in medical AAL technology. The first aim was

to explore why and under which conditions people

trust the medical system. The second aim was to

explore how and under which conditions people trust

medical AAL technology. As the nature of this study

was exploratory, there were no expectations about the

outcomes. Based on previous literature searches,

three categories of trust influences could be outlined,

namely technology factors, user factors, and context

factors (Xu et al., 2014; Bova et al., 2006). The results

of this study suggest that these categories also fit the

answers given by the participants.

5.1 Trust Issues for the User Factors

In the category User Factors, participants mentioned

that trust is generally associated with time and

experience, meaning that that while there is a basic

level of trust, only time and experience will

strengthen this feeling sustainably. Moreover,

participants also felt that honesty and credibility were

important for trusting someone. This is shown by

words, but also with actions that signal integrity and

commitment to the relationship. Lastly, most of the

participants agreed that a serious betrayal of trust

would either result in the termination of the

relationship or could not be fully restored. On the

other hand, others mentioned that, while it is a long

process, trust could be regained over time and with

continuous action that both parties want to reconnect.

Ultimately, this category revealed the importance of

consistent behaviour in the formation of trust and in

the maintenance of it. This suggests a predisposition

of trust but also shows that for the majority of people,

time and trusting behaviour is a key component.

Relating these results back to existing literature, there

is congruency between past studies and this one,

namely that there are specific influences of user

characteristics which alter the overall acceptance of

these technologies (Wilkowska & Zielfe, 2018; Xu et

al., 2014).

5.2 Trust Issues for the Technology

Factors

In the category Technology Factors, answers closely

overlapped with the aspects mentioned for general

trust. Participants felt that AAL technologies should

have the same qualities as humans, i.e. knowledge or

correct results, honesty and integrity, and

benevolence. While the reactions were mostly

enthusiastic, some participants were also concerned

about their data being stored, although this was

strongly related to who had access to it. Moreover,

other concerns were with regard to the lack of

empathy and warmth provided by the technology and

the error rate, i.e. to which extent the technology

gives incorrect data and alarms. Overall, participants

agreed that the technology should not be a

replacement of health care workers but an

enhancement for them. The aspects that were

mentioned in this category are in line with literature

on medical technology, but also with other contexts,

such as autonomous driving, E-commerce, and

internet application, e.g., Facebook & Excel

(McKnight, 2011; McKnight & Chervany, 2014;

McKnight and Chervany, 2001; Montague et al.,

2009, Hengstler et al., 2016).

5.3 Trust Issues for the Context Factors

In the category Context Factors, the results outline

the dependent relationships of trust within the

medical system and the participant’s social context.

Most participants mentioned an emotional

component related to the treating physician, i.e., that

they felt taken seriously and that the physician paid

attention to their concerns. Moreover, they looked for

expertise and knowledge when confiding in health

care workers. The most common line of reasoning

was that they did not have the training themselves and

were obliged to believe a professional. In line with

this, the results suggest that if they trusted their

primary care worker, they would be more open to

trying new technology. This was under the condition

that the person introducing it to them was also skilled

at using and explaining it, and the participants were

informed about data handling. With regard to living

arrangements, it became clear that there was a higher

acceptance and more enthusiasm about AAL

technology if they either lived alone or if it relieved

burden of care on their family members and by

extension, health care workers. Conversely, most of

them did not believe AAL technology could provide

the same quality of medical care than human medical

care. Within the literature, there are studies validating

some of the aspects, i.e. experience of the physician,

information about the technology and perception of

how health care worker use the technology (Bova et

al., 2006; Qiao et al., 2015). In this study however,

there was a proportionally bigger association of

human care and AAL technology than in other

existing studies that could be found. This implies a

strong moderation of context factors on trust in

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

250

medical technology. Moreover, other studies have

also found an association of living situation and social

support on the acceptance and trust of medical

technology, signalling coherence with findings of this

study (Offermann-van Heek et al., 2019; Jaschinski &

Allouch, 2017).

5.4 Strengths and Limitations

This study was exploratory in nature which can

considered a strength since it set out to capture

unbiased opinions and concerns of trust in the

medical context. It was structured from very general

questions to specific scenarios, enabling the

participants to freely associate. Moreover, the sample

was relatively balanced, with four people of younger

age, four people of middle age, and three people of

advanced age. Six of the eleven participants were

female, and there were six people with care

experience, either personally or due to their

profession. Lastly, the results were in line with

previous research, suggesting that the approach was

appropriate for this research question. As with every

study, there are also limitations to consider. Firstly,

the sample was entirely German, limiting the

generalisability with regard to cultural implications.

Secondly, while the exploratory approach has its

advantages, there are downsides to it as well. Because

of the generic approach, many important feelings and

thoughts might not have been captured and could be

explored more precisely in future studies. Moreover,

the features of AAL technologies were described

superficially which might have made it difficult for

participants to imagine a specific, tangible camera or

sensor. Some of the participants also mentioned that

they could not imagine a specific technology

performing these actions and mostly referred to

devices that they have had contact with, e.g., fitness

tracker and emergency wrist bands. Ideally,

participants can physically try out AAL technology

for them to have a more realistic and less scenario-

based experience.

6 IMPLICATIONS: RESEARCH

AND APPLICATION

Given the results of this study, the next step is to

operationalise the aspects and concerns into a scale

with the goal of quantifying them. While the

qualitative approach is useful for an idiographic view

on perceptions of trust, it is necessary to strengthen

the validity of the results and expand their

generalisability with a systematic, quantitative

approach. On the basis of these results, future studies

might focus on specific variables and their individual

influence on trust development in the context of AAL

technologies. As the results revealed three major

categories, future studies can direct their focus on

each of these individually and in due time, address

them in a network of all relevant factors. With the

ultimate goal of mapping trust in the health care

context, this study served as a first step for outlining

idiographic factors and concerns by potential users.

Consequentially, these have to be considered in a

quantitative context with clearly defined parameters.

This will build the foundation to investigate trust

from a psychometric perspective and ultimately, each

influence could be integrated into a model of trust in

health care contexts and AAL technology, for other

researchers to disseminate and corroborate. Finally,

future research could benefit from experimental

studies that look at trust not only from a correlational

or even scenario-based perspective but can

investigate causal mechanisms of important variables

in the health care and AAL context. Moreover, as the

concept of trust in the medical system and medical

technology is of relevance in all cultural settings, the

socio-cultural influences could be explored by

investigating the research aims in different countries.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In line with previous research, this study has shown

that trust is a multi-factor concept embedded in a

network of variables that interact with each other.

This has implications for professionals in various

areas of expertise. However, more research,

specifically with a larger sample, is needed to validate

and corroborate these preliminary findings. This

study has implications for not only researchers in the

field, but also clinicians, policy makers and

developers of medical technology. Trust is not one

variable influencing another but is embedded in a

network of mediators and moderators, most

prominently physicians and care personnel but also

independent institutes and health insurance

companies. In addition, developers can make use of

specific user requirements, such as data handling and

specifically error rates and accuracy measures, when

conceptualising AAL technology and specifically

training of clinicians and health care workers that are

the first to introduce medical AAL technology to

(future) users. Developers could also incorporate the

technological requirements of the users in the design

of AAL technology, such as perfecting the error rate

Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology

251

and optimising the user interface. On a higher level,

policy makers and legal professionals might benefit

from incorporating general protocols that respect the

users’ need of feeling heard and being informed. This

could be implemented in specific training for health

care workers which in turn, might increase trust of the

users in their treating care personnel.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants for their

participation and willingness to share their

experiences. This project has received funding from

the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and

innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-

Curie grant agreement No 861091. The researchers

also thank Alexander Hick, Caterina Maidhof, and

Julia Offermann for research support.

REFERENCES

Bova, C., Fennie, K. P., Watrous, E., Dieckhaus, K., &

Williams, A. B. (2006). The health care relationship

(HCR) trust scale: Development and psychometric

evaluation. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 477-

488. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20158

Climent-Perez, P., Spinsante, S., Mihailidis, A., & Florez-

Revuelta, F. (2020). A review on video-based active

and assisted living technologies for automated

lifelogging. Expert Systems with Applications, 139.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112847

De Ruyter, B. D., & Pelgrim, E. (2007). Ambient assisted-

living research in carelab. Interactions, 14(4), 30-33.

doi: 10.1145/1273961.1273981

Jaschinski, C., & Allouch, S. B. (2017). Voices and views

of informal caregivers: Investigating ambient assisted

living technologies. Ambient Intelligence, 110. 110-

123. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56997-0_8

Hengstler, M., Enkel, E., & Duelli, S. (2016). Applied

artificial intelligence and trust - The case of autonomous

vehicles and medical assistance devices. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 105, 105-120.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.12.0 14

Himmel, S., & Ziefle, M. (2016). Smart home medical

technologies: Users’ requirements for conditional

acceptance. I-com, 15(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.15

15/icom-2016-0007

Jaschinski, C., & Allouch, S. B. (2015). An extended view

on benefits and barriers of ambient assisted living

solutions. International Journal on Advances in Life

Sciences 7(1-2). 40-53.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An

integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of

Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

McKnight, D. H., Carter, M., Thatcher, J. B., & Clay, P. F.

(2011). Trust in a specific technology: An investigation

of its components and measures. ACM Transactions on

management information systems, 2(2), 1-25.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1985347.1985353

McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2001). What trust

means in e-commerce customer relationships: An

interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International

Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6(2), 35-59.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2001.11044235

Memon, M., Wagner, S. R., Pedersen, C. F., Beevi, F. H.

A., & Hansen, F. O. (2014). Ambient assisted living

healthcare frameworks, platforms, standards, and

quality attributes. Sensors, 14(3), 4312-4341.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s140304312

Michel, J. P., & Ecarnot, F. (2020). The shortage of skilled

workers in Europe: Its impact on geriatric medicine.

European Geriatric Medicine, 11(3), 345-347.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00323-0

Montague, E. N., Kleiner, B. M., & Winchester III, W. W.

(2009). Empirically understanding trust in medical

technology. International Journal of Industrial

Ergonomics, 39(4), 628-634. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ergon.2009.01.004

Offermann-van Heek, J., Schomakers, E. M., & Ziefle, M.

(2019). Bare necessities? How the need for care

modulates the acceptance of ambient assisted living

technologies. International journal of medical

informatics, 127, 147-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.ijmedinf.2019.04.025

Offermann-van Heek, J., & Ziefle, M. (2019). Nothing else

matters! Trade-offs between perceived benefits and

barriers of AAL technology usage. Frontiers in Public

Health, 7, 134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00

134

Peek, S. T. M., Wouters, E. J. M., van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K.

G., Boeije, H. R., & Vrijhoef, H. J. M. (2014). Factors

influencing acceptance of technology for aging in

place: A systematic review. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 83(4), 235–248. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.01.004

Qiao, Y., Asan, O., & Montague, E. (2015). Factors

associated with patient trust in electronic health records

used in primary care settings. Health Policy and

Technology, 4(4), 357-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.hlpt.2015.08.001

Schomakers, E. M., Biermann, H., & Ziefle, M. (2021).

Users’ Preferences for Smart Home Automation–

Investigating Aspects of Privacy and Trust. Telematics

and Informatics, 64, 101689.

Steinke, F., Fritsch, T., Brem, D., & Simonsen, S. (2012).

Requirement of AAL systems: Older persons' trust in

sensors and characteristics of AAL technologies. In

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on

Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive

Environments (pp. 1-6). https://doi.org/10.1145/2413

097.2413116

VERBI Software. (2017). MAXQDA 2018 [computer

software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software.

Available from maxqda.com.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

252

Wichert, R., Furfari, F., Kung, A., Tazari, M. R. (2012):

How to overcome the market entrance barrier and

achieve the market breakthrough in AAL. In: Wichert

R., Eberhardt B. (eds) Ambient Assisted Living.

Advanced Technologies and Societal Change. Springer,

Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-

27491-6_25

Wilkowska, W., Offermann-van Heek, J., Florez-Revuelta,

F., & Ziefle, M. (2021). Video cameras for lifelogging

at home: Preferred visualization modes, acceptance,

and privacy perceptions among german and turkish

participants. International Journal of Human–

Computer Interaction 37(15), 1436-1454.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2021.1888487

Wilkowska, W., & Ziefle, M. (2018). Understanding trust

in medical technologies. 4th International Conference

on Information and Communication Technologies for

Ageing Well and E- Health. SCITEPRESS. (pp. 62-73).

World Health Organization. (2002). Active ageing: A policy

framework (No.WHO/NMH/NPH/02.8). World Health

Organization.

Xu, J., Le, K., Deitermann, A., & Montague, E. (2014).

How different types of users develop trust in

technology: A qualitative analysis of the antecedents of

active and passive user trust in a shared technology.

Applied Ergonomics, 45(6), 1495-1503.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2014.04.012

Ziefle, M. (2021). Ambient Assisted Living. In

Telemedizin (pp. 451-466). In: Marx G., Rossaint R.,

Marx N., (eds) Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-66260611-7_40

Ziefle, M., & Valdez, A. C. (2017). Domestic robots for

homecare: A technology acceptance perspective.

In International Conference on Human Aspects of IT

for the Aged Population(pp. 57-74). Springer, Cham.

Exploring Trust Perceptions in the Medical Context: A Qualitative Approach to Outlining Determinants of Trust in AAL Technology

253