To the Next Level! an Exploratory Study on the Influence of User

Experience on the Acceptance of a Gamified Learning Platform

La

´

ısa Paiva, Mois

´

es Barbosa, Solano Oliveira, Max Barbosa, Victor Klisman, Jos

´

e Carlos Duarte,

Genildo Gomes, Bruno Gadelha and Tayana Conte

Institute of Computing, Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), Manaus-AM, Brazil

Keywords:

Gamification, User Experience, Usability, Teaching Platforms.

Abstract:

Gamification is associated with using game elements in different contexts, and one of these is the educational

environment. The education area’s motivation for this concept assumes that gamification provides an alter-

native to motivate and engage students during the learning process. For this, it is common to use gamified

teaching platforms, wherein the experience of students and teachers using these platforms impacts the suc-

cess of their adoption. This paper presents an evaluation of the Classcraft gamified learning platform, aiming

to investigate the User Experience (UX) and usability of this platform and how these elements influence its

acceptance. We performed an empirical study with a group of high school students to investigate how UX-

related factors influence platform acceptance. As a result, we identified that the students do not consider the

platform’s visual elements attractive, with insufficient stimulus for its use. Furthermore, we also noted the

platform’s low attractiveness and usability through the AttrakDiff results. These results show that using gam-

ification in educational platforms does not mean it will reach a good level of acceptance. To achieve that, it is

essential to also look forward to the usability and UX of those platforms.

1 INTRODUCTION

Learning-focused gamification emerges as a possibil-

ity to connect school to young people by not focus-

ing only on traditional forms of school assessments,

but using them combined with game mechanics to

promote experiences that involve students emotion-

ally and cognitively (Anastasiadis et al., 2018). Thus,

gamification uses game design techniques, such as

aesthetics, mechanics, and dynamics, in non-game

contexts (Kapp, 2012).

The growing research in this area (Majuri et al.,

2018) can be explained by the potential of gamifica-

tion to influence, engage and motivate people (Kapp,

2012). Along with it, the educational area pursues

pedagogical approaches that consider the cognitive

experiences of students. One of these approaches is

using technologies to improve learning (Broadbent

et al., 2020).

In this scenario, approaches using gamification are

increasingly present in educational processes (Tsay

et al., 2018). Thus, understanding which aspects and

factors influence pedagogical practices in a gamified

environment is important. The effectiveness of this

environment depends on factors such as acceptability

by users, adaptation to player profiles, and ease of en-

vironment’s use (Sanchez et al., 2017). These aspects

are directly related to the Usability (International Or-

ganization for Standardization, 2019) and User Expe-

rience (UX) concepts(Hassenzahl, 2018).

Thus, there is a need to evaluate gamified teach-

ing platforms to discover the impacts on students’

experience and learning. Therefore, this paper aims

to investigate the UX and the usability of a gamified

teaching platform and discuss how these elements in-

fluence its acceptance. Thus, we intend to evaluate a

gamification platform from the UX and Usability per-

spective. Furthermore, this work can contribute to the

creation of techniques aimed to measure the quality

of gamification platforms and to serve as a basis for

creating guidelines for this type of platform.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Usability and UX

Usability is defined as “the extent to which a system,

product or service can be used by specified users to

Paiva, L., Barbosa, M., Oliveira, S., Barbosa, M., Klisman, V., Duarte, J., Gomes, G., Gadelha, B. and Conte, T.

To the Next Level! an Exploratory Study on the Influence of User Experience on the Acceptance of a Gamified Learning Platform.

DOI: 10.5220/0011067900003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 281-288

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

281

achieve specific goals effectively, efficiently and sat-

isfyingly in a specified context of use” (International

Organization for Standardization, 2019). It is associ-

ated with: ease of learning, ease of remembering how

to perform the task after some time, speed in perform-

ing tasks, low error rate and user satisfaction (Nielsen,

1994). An interface that does not offer good usabil-

ity is considered a problematic interface, which can

cause losses to the user and even the rejection of the

product or service (Monz

´

on et al., 2020).

UX covers all aspects of the interaction with a

product, containing perceptions and responses, which

can be pragmatic aspects related to effective and ef-

ficient goals, and hedonic aspects related to users’

feelings and well-being (Hassenzahl, 2018). Sev-

eral methods are available to assess usability and UX

(Rajeshkumar et al., 2013). One usability inspec-

tion technique is the Heuristic Evaluation proposed

by Nielsen [1994], which consists of an expert review

in which an expert in usability uses a set of 10 heuris-

tics to identify and classify usability problems in the

interface.

A scale-type technique for evaluating UX is At-

trakDiff (Hassenzahl, 2018), which captures users’

pragmatic and hedonic perceptions of a product af-

ter its use through a questionnaire containing seman-

tic differential scales. This questionnaire has 28-word

pairs divided into 4 dimensions where the extremes

are opposite adjectives (e.g., “good-bad”, “clear -

confused”) ordered on a Likert scale of 7 points.

The mean values of the word pair groups result in

one value for each of the 4 dimensions: Pragmatic

Quality(PQ), Hedonic Quality - Identity(HQ-I), He-

donic Quality - Stimulation(HQ-S), and Attractive-

ness(ATT). PQ is associated with the ease with which

users can manipulate the software. HQ–I refers to the

user being able to identify with the software in a so-

cial context. HQ-S is related to people’s desire to de-

velop their skills and psychological well-being, such

as feeling competent and connected to others (Has-

senzahl, 2004). ATT summarizes the entire product

experience and is used to measure the global appeal

of a product and how it affects users’ judgment as a

whole (Hassenzahl, 2018).

2.2 Gamification in Education

The emergence of modern technologies and their

successful application in teaching and learning have

changed the educational system of schools and uni-

versities (Shen and Ho, 2020).The result of this ubiq-

uitous digital environment, and the sheer volume

of their interaction with it, is that today’s students

think and process information fundamentally differ-

ently from their predecessors (Prensky, 2001).

In this sense, approaches and methods that pro-

vide more active participation of students are increas-

ingly important. The use of gamification, for ex-

ample, improves the ability to learn new skills by

40% (Kiryakova et al., 2014). Furthermore, game ap-

proaches lead to a higher level of commitment and

motivation with the activities and processes that in-

volve students (Castro et al., 2018).

While gamification techniques are adopted to sup-

port classroom content learning in specific areas, they

are also employed to pursue cross-cutting objectives

such as promoting participatory approaches, peer col-

laboration, self-guided learning, and homework as-

signment, thus making the assessment procedures

easier and effective. Besides that, gamification pro-

vides integration of exploratory learning approaches

and strengthens students’ creativity (Caponetto et al.,

2014).

2.3 The Classcraft Platform

Classcraft

1

is an educational multidisciplinary gami-

fication platform that aims to promote collaboration

among students. Furthermore, it seeks to encour-

age learning through rewards in a role-playing game,

where people play characters in a fictional world with

its own Classcraft narrative. The platform allows

the teacher to create a dynamic and fun environment

for students by creating missions, it is also possible

to expand the game for parents, who can view their

children’s stats in class and assign points at home.

(Sanchez et al., 2017).

3 METHODOLOGY

To investigate the UX and usability of a gamified

learning platform and how these elements influence

its acceptance, we conducted a study on the Classcraft

Web version platform with a group of high school stu-

dents.

The study consisted of five steps. In the selection

step, we defined the Classcraft platform as a tool to

be evaluated, as it is an established platform in the

market and used by schools in different countries. In

the usability assessment planning stage (Subsection

3.1), we defined the students’ tasks on the platform,

the Consent Form, the usability metrics, and the as-

sessment technique. Also, at this stage, the partici-

pating students’ profile is defined. After that, we car-

ried out the usability assessment of the platform with

1

Classcraft website: https://www.classcraft.com/

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

282

high school students. Next, we applied the AttrakDiff

questionnaire to assess users’ perceptions and emo-

tions while using the platform.

We performed a heuristic inspection of the plat-

form to identify which aspects of Nielsen’s (1994)

heuristics are affected. In this step, described in Sub-

section 4.3, we identified several usability problems.

Finally, in the analysis of results step, we organized

the results obtained in the previous stages in tables

and graphs for better visualization and analysis. We

present a discussion of the results in Section 5.

3.1 Usability Assessment Planning

To carry out the study, we defined criteria for students

participation considering the context of the COVID-

19 pandemic and social distancing. We selected ten

2

nd

and 3

rd

-year high school students from public and

private schools.

To prepare the assessment with students, we pre-

viously conducted a pilot test with a student who had

experience using the platform. From this pilot test, we

defined the following tasks: (1) create an account; (2)

customize a character; (3) access the missions’ menu;

(4) execute the first mission; (5) choose a pet; (6) buy

a skin; and (7) send a message to the teacher.

Also, for the clarification, protection, and preser-

vation of participants’ image and data, we prepared

a Consent Form through the Google Forms platform

and the AttrakDiff technique through their online plat-

form

2

.

3.1.1 Usability Metrics

We defined the following usability metrics: task

completion time and the number of help requests.

These metrics define software product quality stan-

dards (ISO / IEC 25022: 2016, 2016). The first metric

allows assessing the efficiency of a system and find-

ing out how long it takes the user to complete a given

task. The second metric allows assessing whether the

system is user-friendly.

In addition, we used the AttrakDiff evaluation

technique to evaluate the UX. We selected this tech-

nique because it allows the identification of qualities

inherent to the tool’s functionalities (pragmatic) and

aspects related to users’ emotions and pleasures (he-

donic) (Hassenzahl, 2018). Moreover, this technique

is strongly related to visual aspects, which are rele-

vant characteristics of a game.

2

http: //www.attrakdiff.de

3.2 Usability Assessment

The study took place both on-site and online. We

conducted the face-to-face study with five students

in a public school class, respecting social distancing.

Regarding the online study, we conducted it through

videoconference with five students from public and

private schools. In both groups, we adopted the same

procedure. We started explaining (i) the motivation

for the study. As the students were underage, we

asked for (ii) their parents’ signature on the Consent

Form. Next, we presented the (iii) context of the

Classcraft platform, the (iv) tasks to be performed by

the students, and the (v) AttrakDiff technique.

Then, we prepared the environment for the exe-

cution of the study, requiring access to the platform

using a computer and a stopwatch to check the time

of each task. When conducting the study individu-

ally with each student through videoconference, we

requested authorization to record the computer screen

during the execution of the tasks. In this way, we col-

lected usability metrics without the need for the stu-

dent to time each task.

In the face-to-face application of the study, we in-

structed the students to register the amount of time for

each task on a stopwatch, as there was no program to

record computer screens and there was no permission

to install third-party software. In addition, we col-

lected the number of help requests when performing

the elaborated tasks.

The assessment took 20 minutes, students an-

swered 3 simple general knowledge questions to cap-

ture their experience with the platform rather than

their mastery of certain content. After using the tool,

the students answered the AttrakDiff questionnaire.

From this technique, we obtained insights about the

tasks performed by the participants and information

about the students’ acceptance of the platform.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Results Portfolio and Average

Values Diagram

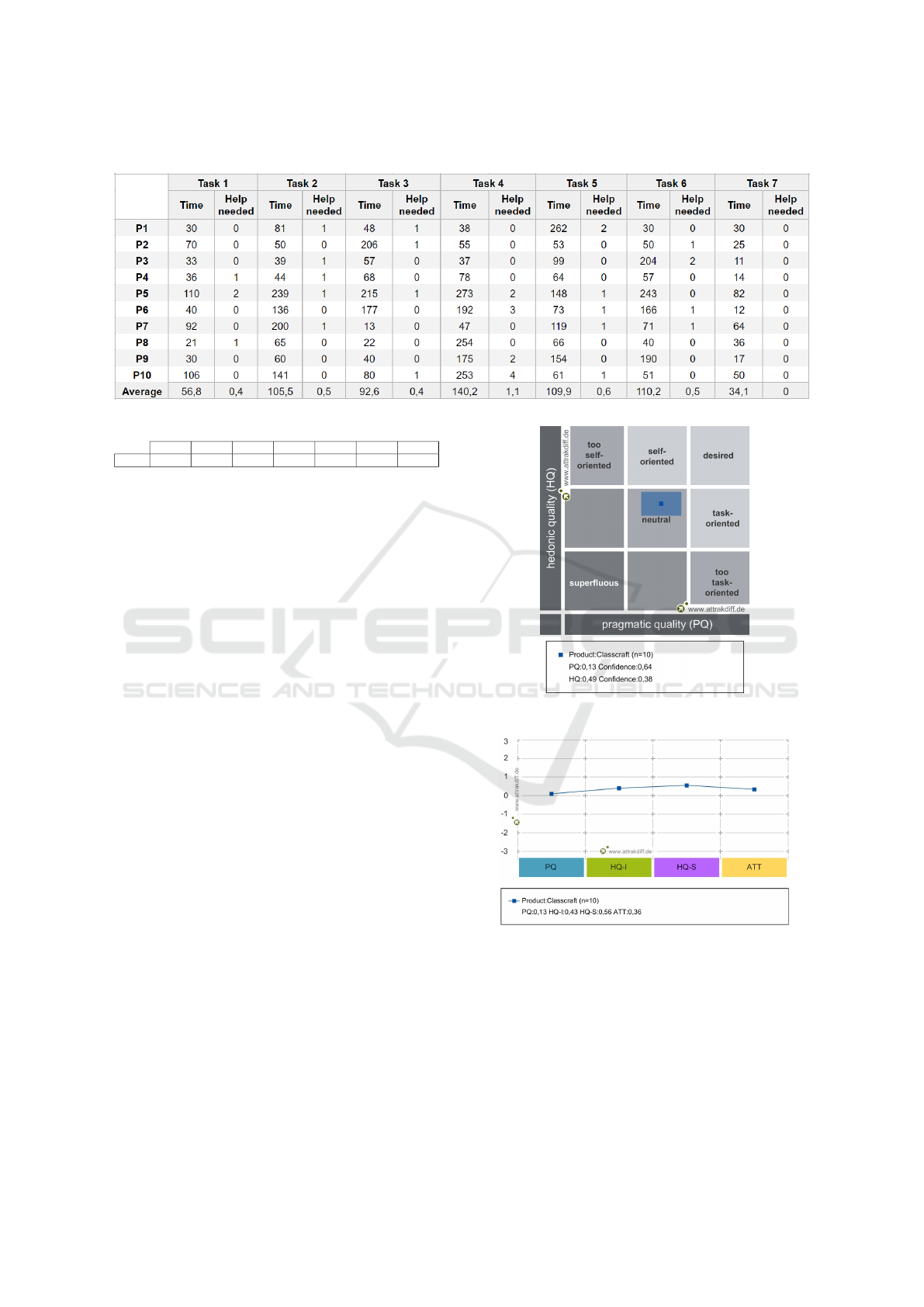

Figure 1 shows the positioning of the mean values of

Pragmatic Quality (horizontal) and Hedonic Quality

(vertical). In addition, 2 rectangles in blue are shown.

The smallest (and darkest) rectangle represents the

average value of the evaluated dimensions, consid-

ering the user experience. The larger (and brighter)

rectangle represents the confidence interval showing

the intensity of how much users’ opinions converge or

diverge: the larger, the more divergent the opinions.

To the Next Level! an Exploratory Study on the Influence of User Experience on the Acceptance of a Gamified Learning Platform

283

Table 1: Data from the usability tests with the participants.

Table 2: Reference values for the performance of each task.

Task 1 Task 2 Task 3 Task 4 Task 5 Task 6 Task 7

Time 31s 58s 9s 80s 35s 106s 8s

The closer to zero the values of these attributes,

the more indifferent they are to the user. The mean

value for Pragmatic Quality (PQ) was 0.13 and 0.49

for Hedonic Quality (HQ). Note that both rectangles

are positioned in the “neutral” quadrant. The results

show a confidence value of 0.64 for PQ and 0.38 for

HQ, indicating that the confidence rectangle reveals

divergent opinions among users and shows percep-

tions about the platform that converges towards neu-

tral.

In the Figure 2, we can see the mean values dia-

gram assigned by users. It is observed that all points

were above or close to 0 (zero), indicating the UX

tends to be more neutral than positive. The PQ dimen-

sion obtained a score tending to neutral (0.13), indi-

cating that the platform does not adequately support

its users in achieving their goals. The HQ-I dimen-

sion also received a score close to neutral (0.43), re-

vealing that the participants did not identify well with

the platform.

The HQ-S dimension measures the originality,

stimulus, and how interesting the application is. The

score of 0.56, indicates that Classcraft arouses little

interest in users. Attractiveness (ATT) represents how

attractive the application is to the user and obtained a

0.36 score, which means users see the application as

unattractive.

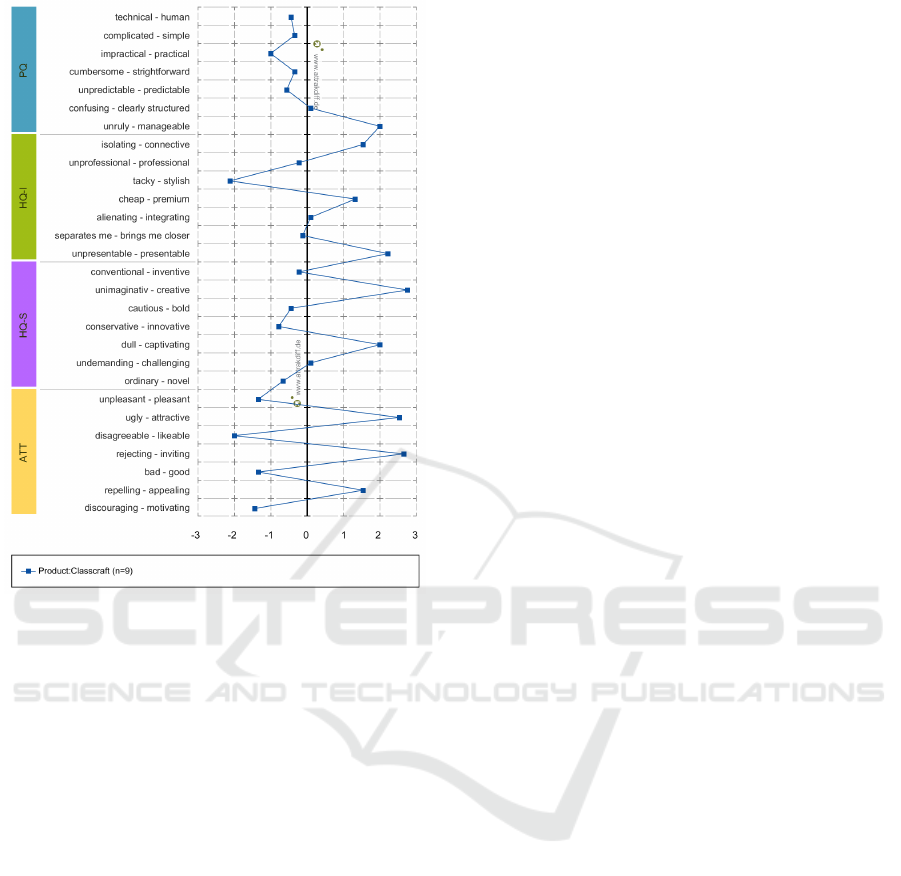

4.2 Description of the Word Pairs

The results shown in the Figure 3 demonstrates diver-

gent usage perceptions by users, but that at some point

converge to neutral. It can be translated as a feeling

of indifference.

It is possible to see that the PQ dimension had

a greater number of negative results. However, the

Figure 1: AttrakDiff: portfolio of results.

Figure 2: AttrakDiff: diagram of mean value of the dimen-

sions.

points stay close to the neutral point, which means

that Classcraft tends to have poor pragmatic quality.

The data on HQ-I dimension suggest that the system

is somewhat connective, but divides opinions, as the

item “tacky - stylish” indicates the tool as “tacky”. On

the other hand, the item “unpresentable – presentable”

reveals that Classcraft is considered by users to be

“presentable”. Conversely, many perceptions are po-

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

284

Figure 3: AttrakDiff: description of word pairs.

sitioned close to neutral, evidencing different points

of view about this dimension.

HQ-S dimension has its highlights in “unimagi-

native - creative” and in “dull - captivating” pairs,

pointing out that users considered the platform cre-

ative and captivating, but not very innovative. This

data indicates that despite not being stylish and not

pragmatic, being creative makes the system captivat-

ing for users. Finally, the ATT dimension presents a

sinuous behavior between the right and left sides of

the graph, showing that Classcraft has contradictory

attractiveness. It is “attractive”, but “disagreeable”; is

“inviting” and, at the same time, “bad”; it is “appeal-

ing” but “discouraging”. Such results reveal extreme

and inconsistent perceptions about the attractiveness

of the tool by users, and it supports the neutral char-

acter presented in the results’ portfolio (Figure 1).

4.3 Heuristic Evaluation

We performed the usability assessment after heuris-

tic evaluation to understand the task execution time

discrepancy between students and whether this is re-

lated to problems of usability. Five expert inspec-

tors with previous experience in usability assessment

performed heuristic evaluations on the platform, with

this, we expected to identify usability problems on

the interface. The inspectors mapped the problems

found according to the heuristics proposed by Nielsen

[1994] identifying 74 unique problems. Duplicates

were excluded and not accounted.

After discrimination and collection for each

heuristic, we obtain the following heuristics prob-

lem’s list: H1. Visibility of system status (8); H2.

Match between system and the real world (5); H3.

User control and freedom (9); H4. Consistency

and standards (23); H5. Error prevention (11); H6.

Recognition rather than recall (10); H7. Flexibility

and efficiency of use (3); H8. Aesthetic and minimal-

ist design (2); H9. Help users recognize, diagnose,

and recover from errors (1); H10. Help and documen-

tation (2).

There are a high number of problems referents to

the heuristics H4, H5, and H6 related to the lack of

confirmation messages before the user takes a criti-

cal action and the lack of standardization of icons and

nomenclatures on the platform’s pages, making the

platform difficult to navigate and understand.

Among the major violations of Nielsen’s heuris-

tics (1994), the ones that most fit as justification for

the difficulty of using the platform and that are di-

rectly linked to the metrics are:

• H1. The lack of a menu with a list of completed

tasks and pending tasks. This lack of clear organi-

zation makes the user unaware of what activities

have already been done and what have not.

• H4. Although there is a pets menu, the pets ac-

quisition and exchange are located in equipment

menu. Consequently, users spend a long time

finding the pet’s customization location, making

them believe that this platform function has not

been implemented yet.

• H4. Users cannot see the pets available for pur-

chase in the pets menu, not even those already

purchased. In this way, the platform tricks the

user into recognizing an icon and not delivering

the expected action of the icon’s representation.

• H4. Most of the icons in the sidebar are barely

recognizable. The same occurs in other platform

parts, such as the tab to deliver activity. As the

icons do not follow universally recognized stan-

dards, users are confused all the time, making it

difficult to find basic platform tasks.

• H4. The field to answer a question/deliver activity

is not on the same tab as the question. This incon-

sistency makes the user click several times on the

screen looking for some field to answer, and even

believe that there is a problem with their computer

or the page loading.

To the Next Level! an Exploratory Study on the Influence of User Experience on the Acceptance of a Gamified Learning Platform

285

These items show a lack of consistency, which can

cause low platform effectiveness, as it makes it diffi-

cult for users to achieve the desired goals during use.

As it does not have a pattern similar to other systems,

this also impairs learning to use the platform.

5 DISCUSSION

The data presented in Table 1 shows that Task 4, car-

rying out the first mission, was the task in which the

students felt the most difficulty. It is the central task of

the platform, where students are expected to be able to

submit their work and receive rewards for progressing

through the game. It is also the environment in which

students have greater contact with gamification and

longer execution time (on average 140.2s) to respond

to the activities the teacher requested. Therefore, it is

a fundamental activity to assess the UX and system

usability.

The Task 4 panel consists of a simple interface

with a map of activities available to students. The

questions in the activities were of general knowledge.

Students did not need to worry about the solution but

to answer them as requested on the platform. Thus,

we considered that the difference in times (the short-

est time being 37s and the longest being 4m33s) to

performing the tasks reflects the users’ understanding

of the platform and not their knowledge of the con-

tent. When visualizing the reference time (80s, Table

2), we expect this task to be a time-consuming task.

However, we did not expect half of the users to take

more than twice the reference time to complete this

task. Thus, we can say that participants’ delay is due

to a poor understanding of the platform. The incon-

sistencies of the tool (heuristic H4) pointed out by the

usability inspection evidenced this issue.

Another disparity observed in the results is con-

cerning Task 2, which deals with character customiza-

tion. We consider that the minimum (39s) and maxi-

mum (3m59s) time is due to the user’s interest in the

platform’s look and the avatar’s attractiveness, given

that the 3 participants who took the longest in this

task (3m59s, 3m20s, and 2m21s) experienced more

customizable items in their avatars than participants

who completed this task faster. Therefore, the longer

time spent on customization reflects the user’s inter-

est in exploring the available options. It becomes even

more evident when we consider the reference time of

this task in Table 2 (58s). This low time is because the

person who carried out the pilot test already knew the

platform and did not bother to explore the character

customization options.

The fact is that, although the user was exploring

all of the character’s customization options (in Tasks

2, 5, and 6), some of these tasks’ completion times are

excessively long. It can be an indication of usability

problems of the tool since the heuristic evaluation was

able to detect inconsistency problems in this part of

the customization present in the system. Among these

problems is the mistaken use of an icon whose action

when clicking on it does not correspond to what is ex-

pected. Moreover, this action is performed in another

part of the platform. As the icon does not act as ex-

pected, the attempt to make the platform more flexi-

ble through a shortcut led to an inconsistency that may

harm the use of the platform. This finding also reflects

the reason for the non-acceptance of Classcraft.

Task 7 was the only one where the participants

had no doubts and did not ask for help. It was also

the fastest task with an average completion time of

34.1s. It can reflect the consistency of the platform in

keeping the message icon pattern, as seen in other sys-

tems, making it easily recognizable by the user. The

non-recognition of icons, as seen in other parts of the

system, detracts from users’ performance on the plat-

form, leaving them lost and confused. On the other

hand, maintaining icon consistency allows the user to

recognize rather than guess its meaning, making the

user experience smooth and intuitive.

Another easy task to perform was Account cre-

ation Task 1, which follows the standards of other

platforms, with an average of 56.8s. Thus, we ob-

served that the simplest tasks are related to aspects

common to conventional systems, such as logging

into the system and sending a message. On the other

hand, the most complex tasks on the platform, which

required more time and more help (Tasks 4, 5, and

6), are related to the reward system and avatar cus-

tomization. Furthermore, these tasks most represent

and use gamification elements and require a greater

interaction flow between the user and the platform.

From the metrics, most participants took a short

period to complete the tasks related to gamification.

There is a contrast concerning a few participants who

took a long time to complete these tasks, which gener-

ated a disparity between the minimum and maximum

time values for each task. Since the delay in cus-

tomization tasks is due to the interest in customiza-

tion and the difficulty of using the platform (as de-

tected in the heuristic evaluation), participants who

took less time on these tasks may not feel attracted by

the gamification process and complete the activities

quickly without enjoying the visuals. The AttrakDiff

word pairs that measure the platform’s attractiveness

can evidence the results. They show that users per-

ceive the platform as attractive and appealing but, on

the other hand, demotivating and unpleasant. Thus,

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

286

the metrics reveal a trend of acceptance difficulty, and

AttrakDiff emphasizes this trend, indicating that the

tool’s gamification does not attract users.

The heuristic evaluation also evidenced these in-

ferences. The results revealed many Consistency and

Standards (H4) problems in the tool. By observing

the pairs of words mentioned above, it is clear that

they reflect this idea of inconsistency, as they demon-

strate contradictory perceptions about the attractive-

ness aspect of the system. Thus, the outcomes from

the AttrakDiff technique show that users considered

Classcraft an unattractive platform. The results indi-

cate that low attractiveness causes a lack of motiva-

tion which, in turn, can hinder the learning process.

It is because learning is a complicated process, and

motivation is the hard rock of this process(Gopalan

et al., 2017). If there is no motivation, there is no good

learning process, and, as a consequence, students re-

ject the tool.

We can verify by the “discouraging – motivating”

word pair in Figure 3, reaching a value of -1 in the

graph. We can also note by the mean values diagram

(Figure 2) that perceptions about the platform tend

to neutral regions, indicating that Classcraft doesn’t

arouse great interest in users. We can also observe

in the “unpleasant - pleasant” pair of Attractiveness

(ATT), in which users rated Classcraft as “unpleas-

ant”.

In addition, the graph in Figure 3 reveals that the

tool has a low pragmatic (PQ) and hedonic (HQ-I

and HQ-S) quality with attractiveness that oscillates

between positive and negative opinions, emphasiz-

ing the inconsistent character captured by heuristic

inspections. It shows that the time values that were

higher than the reference time (Table 2) in some tasks

are not necessarily because they feel captivated or be-

cause they liked the gamification of the tool, but be-

cause of the problems encountered during its execu-

tion.

From the results presented in Section 4, we can

note the platform does not arouse the necessary stim-

ulus for strong acceptance, as users classified the plat-

form as mostly neutral, as can be seen in Figure 1.

An interesting point is found in the attractiveness of

AttrakDiff, where the results were divergent, show-

ing that the platform is not seen as attractive by most

users. This is reflected in the hedonic quality part of

the tool, in which students rated Classcraft as “tacky”,

meaning something of little appeal.

Thus, the results indicate that, for the Classcraft

platform to have gamification capable of captivating

and stimulating students during the learning process,

it is necessary to review its attractiveness. Therefore,

the importance of a good gamification process is ver-

ified, not limited to its structuring, but considering

the pragmatic, hedonic, and attractiveness perceptions

of a learning platform, for the interaction and experi-

ence of use to be consistent and encourage users’ and

arouse their interest. So it is not worth using a gami-

fied tool to support education if the user cannot use it

and does not feel attracted to it.

The results show that the platform’s cognitive

qualities are weak and not so relevant. However, the

standpoint of learning not only draws attention to cog-

nition but also the students’ motivation and prefer-

ence, which are among the fundamental factors for

effective and useful learning (Gopalan et al., 2017). It

means that not only the low cognitive quality of the

platform but also the lack of motivation due to the

lack of attractiveness, negatively influence the learn-

ing process. Since the platform Classcraft does not

arouse the students’ interest, its use as an education

supporting tool becomes compromised.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented research that aimed to investi-

gate the usability and UX of a gamified learning plat-

form and how these factors influence its acceptance.

The results indicate that the students see the platform

as creative but tacky, which reverberates in the UX.

In addition, students do not find the visual elements

attractive, and AttrakDiff dimensions point to neutral,

which causes a feeling of indifference instead of ac-

ceptance.

The gamified environment is motivating for the

student, but the tool’s low attractiveness makes stu-

dents negatively evaluate the platform. This behav-

ior indicates that the UX of the platform is a deci-

sive factor in educational tools that use gamification.

From an educational point of view, the demotivation

and the low pragmatic and hedonic qualities of the

Classcraft platform hamper the learning process, as

students do not see it as attractive and motivating. The

students lose interest if there is no motivation, which

negatively impacts the learning process. These fac-

tors reduce the platform’s potential as an education-

supporting tool.

Consequently, for users to accept a gamified plat-

form, it is necessary also focus on the usability of el-

ements that do not involve gamification, such as the

platform navigation itself. Thus, for a gamified plat-

form to be accepted from the UX point of view, it

must have minimal attributes of hedonic quality, prag-

matic quality and attractiveness tending towards pos-

itive scores, as these attributes generate encourage-

ment, clarity, and aesthetic quality. In future works,

To the Next Level! an Exploratory Study on the Influence of User Experience on the Acceptance of a Gamified Learning Platform

287

we aim to create guidelines for developing these tools

and investigate the influence of variables such as age

and experience with games on students perceptions of

the UX conveyed by educational platforms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research, carried out within the scope of the

Samsung-UFAM Project for Education and Research

(SUPER), according to Article 48 of Decree nº

6.008/2006(SUFRAMA), was funded by Samsung

Electronics of Amazonia Ltda., under the terms

of Federal Law nº 8.387/1991, through agreement

001/2020, signed with Federal University of Ama-

zonas and FAEPI, Brazil. This research was also

supported by the Brazilian funding agency FA-

PEAM through process number 062.00150/2020, the

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Ed-

ucation Personnel-Brazil (CAPES) financial code

001, the S

˜

ao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

under Grant 2020/05191-2, and CNPq processes

314174/2020-6. We also thank to all participants of

the study present in this paper.

REFERENCES

Anastasiadis, T., Lampropoulos, G., and Siakas, K. (2018).

Digital game-based learning and serious games in ed-

ucation. International Journal of Advances in Sci-

entific Research and Engineering (ijasre), 4(12):139–

144.

Broadbent, J., Panadero, E., Lodge, J. M., and de Barba,

P. (2020). Technologies to enhance self-regulated

learning in online and computer-mediated learning

environments. In Handbook of research in educa-

tional communications and technology, pages 37–52.

Springer.

Caponetto, I., Earp, J., and Ott, M. (2014). Gamification

and education: A literature review. In European Con-

ference on Games Based Learning, volume 1, page 50.

Academic Conferences International Limited.

Castro, K. A. C., Sibo,

´

I. P. H., and Ting, I.-h. (2018). As-

sessing gamification effects on e-learning platforms:

An experimental case. In International Workshop on

learning technology for education in Cloud, pages 3–

14. Springer.

Gopalan, V., Bakar, J. A. A., Zulkifli, A. N., Alwi, A., and

Mat, R. C. (2017). A review of the motivation theories

in learning. In AIP Conference Proceedings, volume

1891, page 020043. AIP Publishing LLC.

Hassenzahl, M. (2004). The interplay of beauty, good-

ness, and usability in interactive products. Human–

Computer Interaction, 19(4):319–349.

Hassenzahl, M. (2018). The thing and i: understanding the

relationship between user and product. In Funology 2,

pages 301–313. Springer.

International Organization for Standardization (2019). ISO

9241-210:2019. Ergonomics of human-system inter-

action — Part 210: Human-centred design for in-

teractive systems. Available in https://www.iso.org/

standard/77520.html. Accessed in July 21, 2021.

ISO / IEC 25022: 2016 (2016). Systems and software engi-

neering — systems and software quality requirements

and evaluation (square) — measurement of quality in

use. Technical report, International Organization for

Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and

instruction: game-based methods and strategies for

training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

Kiryakova, G., Angelova, N., and Yordanova, L. (2014).

Gamification in education. Proceedings of 9th Inter-

national Balkan Education and Science Conference.

Majuri, J., Koivisto, J., and Hamari, J. (2018). Gamifica-

tion of education and learning: A review of empiri-

cal literature. In Proceedings of the 2nd international

GamiFIN conference, GamiFIN 2018. CEUR-WS.

Monz

´

on, I., Angeleri, P., and D

´

avila, A. (2020). Design

techniques for usability in m-commerce context: A

systematic literature review. In International Confer-

ence on Software Process Improvement, pages 305–

322. Springer.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability engineering. Morgan Kauf-

mann.

Nielsen, J. and Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation of

user interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI confer-

ence on Human factors in computing systems, pages

249–256.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part

2: Do they really think differently? On the horizon.

Rajeshkumar, S., Omar, R., and Mahmud, M. (2013). Tax-

onomies of user experience (ux) evaluation methods.

In 2013 International Conference on Research and In-

novation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), pages 533–

538. IEEE.

Sanchez, E., Young, S., and Jouneau-Sion, C. (2017). Class-

craft: from gamification to ludicization of classroom

management. Education and Information Technolo-

gies, 22(2):497–513.

Shen, C.-w. and Ho, J.-t. (2020). Technology-enhanced

learning in higher education: A bibliometric analysis

with latent semantic approach. Computers in Human

Behavior, 104:106177.

Tsay, C. H.-H., Kofinas, A., and Luo, J. (2018). Enhancing

student learning experience with technology-mediated

gamification: An empirical study. Computers & Edu-

cation, 121:1–17.

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

288