Beyond the Digital Divide: Digital Skills and Training Needs of

Persons 50+

Veronika Hämmerle, Julia Reiner

a

, Esther Ruf

1b

, Stephanie Lehmann

c

and Sabina Misoch

d

Institute for Ageing Research, OST Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences,

Rosenbergstrasse 59, St.Gallen, Switzerland

Keywords: Digital Divide, Digital Skills, Older Adults, Training Needs.

Abstract: Demographic change and digitalisation are two megatrends which change society and individual life

fundamentally. Digital skills and their continuous development are increasingly central prerequisites for

participation in private and public life, and it must be ensured that all citizens can develop the skills necessary

to participate and to access services. However, these skills are not equally developed in all population groups,

an unequal distribution of ICT use, digital skills, and its outcomes, the so-called “digital divide”. However,

using a binary classification of Internet use or skills overlooks the broad differences in people’s level of skills.

Due to the static and dichotomous theoretical conception, there is a high risk of overlooking the group of

people who, in a continuum of digital skills, are not at either end but somewhere in the middle. Especially

with persons in the second half of life, due to their biography as they did not grow up with digitalisation but

acquired basic skills during their professional lives, a high percentage of people with intermediate digital

skills can be assumed. This group is at risk of being overlooked in the context of digital skills courses, which

often focus on building basic skills. Strategies and programs should be developed to support the further

development of digital skills of this group during and especially beyond working life. Therefore, a mixed-

method study, entitled “Digital Skills and Training Needs of 50+. A Study Beyond the Digital Divide”, is

conducted by the Institute for Ageing Research (IAF), OST – Eastern Switzerland University of Applied

Sciences, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) within the program NRP 77 “Digital

Transformation”. The project will generate broad knowledge of actual and long-term digital competences of

Swiss people 50 plus, their training experiences, as well as develop evidence-based recommendations for

stakeholders wishing to design new training courses on digital competences for people 50 plus with different

educational backgrounds and experiences. This project provides actual and long-term broad knowledge and

practical application possibilities to ensure the participation of future generations in digitalisation in

Switzerland. This paper presents in detail the project, its individual parts and the methodological approach..

1 INTRODUCTION

Demographic change worldwide and in Switzerland

is leading to a significant increase in the number of

older adults in the population (Federal Statistical

Office, 2020; Vaupel, 2000). In parallel all areas of

society are being transformed by digitalisation

(Tsekeris, 2018). These two megatrends will change

society and individual life fundamentally. Despite

these changes and developments, it must be ensured

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9950-5740

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0520-9538

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1086-3075

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0791-4991

that all citizens, including older adults, can develop

the skills necessary to participate in public and social

life and to access health-services as well as other

services. In an increasingly digitalised society digital

competences and skills and their continuous

development are essential (European Commission,

2018; Ferrari, Punie, and Brečko, 2013).

The European Commission (2018) defines Digital

Competence as “the confident, critical and creative

use of ICT to achieve goals related to work,

employability, learning, leisure, inclusion and/or

276

Hämmerle, V., Reiner, J., Ruf, E., Lehmann, S. and Misoch, S.

Beyond the Digital Divide: Digital Skills and Training Needs of Persons 50+.

DOI: 10.5220/0011068200003188

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2022), pages 276-282

ISBN: 978-989-758-566-1; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

participation in society. Digital Competence is a

transversal key competence which, as such, enables

acquiring other key competences (e.g. language,

maths, learning to learn, creativity). It is amongst the

so-called 21st Century skills which should be

acquired by all citizens, to ensure their active socio-

economic participation in society and the economy.”

A basic framework for digital competences for all

citizens is provided from the European DigCOMP

project, listing competences and describing them in

terms of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The main

areas of digital competence identified by the

DigCOMP (2020) framework are information,

communication, content-creation, safety and

problem-solving (Ferrari et al., 2013, p. 4).

1.1 Digital Divide

However, the use of ICT and digital skills are not

equally developed in all population groups. To capture

this inequity, the term “digital divide” emerged in the

mid-1990s. Up to now, it still dominates the discourse on

the societal distribution of digital competences

(Castells, 2002; Eastin, Cicchirillo, and Mabry, 2015;

Friemel, 2016). The Organisation for Economic Co-

operation and Development (OECD, 2001) defines

the digital divide as differences between individuals,

households, companies, or regions related to the

access to and usage of ICT. These inequalities in

access to the Internet and usage of ICT are also called

the “first-level digital divide” (Van Dijk, 2005). The

concept has received much attention, partly because

the digital divide is seen as the practical embodiment

of the wider theme of social inclusion (Selwyn,

2004). Over time, broadband Internet access and

digital devices became more prevalent in developed

countries, and the diffusion of the Internet among

households reached high levels. With time, the digital

divide discourse shifted from Internet access to issues

of Internet skills, which was then referred to as

“second-level digital divide” (Hargittai, 2002; Tsai,

Shillair, and Cotten, 2017; Van Dijk, 2005). Further,

it was found that although Internet access exists and

digital skills are available, outcomes of Internet use

are not necessarily beneficial, a discussion resulting in

the term “third-level digital divide” (Stern, Adams,

and Elsasser, 2009; Van Deursen, Helsper, and

Eynon, 2016; Wei, Teo, Chan, and Tan, 2011).

In order to counteract these divides and the

resulting disadvantages, various efforts have been

made to get people, including older adults, online and

to provide basic digital skills. The underlying

assumption is that once someone is online, they will

remain ‘digitally engaged’ (Olphert and Damodoran,

2013, p. 564). However, in their review, Olphert and

Damodoran (2013) found statistics showing that some

users give up using the Internet and that there is

emerging evidence that older adults in particular tend

to do so (in the sense of a so-called “fourth digital

divide”, Olphert and Damodoran, 2013).

Over time, the complexity of the so-called digital

divide became obvious and critical perspectives on the

concept emerged, e. g. concerning its range resp.

dichotomy (Wang, Myers, and Sundaram, 2013). This

primarily emerged due to the wide gap within the

generations, especially at the beginning of the

ongoing digitalisation. Referred to the dichotomy

between non-user and user, a distinction is (still often)

made between so-called digital natives, defined as

generation Y (born between 1980-1999) and digital

immigrants, who were born earlier and thus, learned

to use computers in adulthood (Prensky, 2001).

Whereas the former ones attributed high

competences, the latter ones regarded to have low

skills resp. knowledge. However, using a binary

classification of Internet use or skills overlooks the

broad differences in people’s level of skills, therefore,

one should talk about a continuum of digital skills.

Additionally to the problem of actual over-

simplification through a dichotomous division into

two groups, the rapidity of technical change supports

the change of perspective to a continuum of digital

skills. For example, it is likely that the use of the

Internet will increase in the future, but the rapid

technological development will also mean that digital

natives will have something new to learn. This does

not just comprises certain practical skills in using the

Internet, but also knowledge resp. awareness of

certain consequences, e. g. questions of sustainability

or digital footprints (Vervier, Zeissig, Lidynia, and

Ziefle, 2017). Moreover, with the rapid (further)

development of modern technologies and the spread

of social media, the concrete manifestations of the

divides in society are constantly changing (Weibert,

Aal, Unbehaun, and Wulff, 2017). In sum, it gets

obvious, that the “digital divide” is not a fixed picture,

but a quite dynamic process with changing inequalities

over time.

1.2 Need for Older Adults Maintaining

Digital Skills

Research on digital inequality so far tended to assign

people over a certain age (resp. from a certain

generation) to a category of "older adults", assuming

that this is a homogeneous group. However, Hargittai

and Dobranski (2017) showed with data from a

national survey in the U.S. that older adults are not

Beyond the Digital Divide: Digital Skills and Training Needs of Persons 50+

277

one homogeneous group with identical online

behaviours. For Switzerland, for example,

Schumacher and Misoch (2017) found

inhomogeneous groups concerning the use of digital

services. It should therefore be noted that concerning

their Internet experience, the group of people 50 plus

cannot be regarded as homogeneous (Stallmann,

2012).

Against the background of these findings and the

theoretical conceptions of Internet use as static (ICT

use) and dichotomous (digital divide), there is a high

risk of overlooking the group of people who, in a

continuum of digital skills, are not at one end but

somewhere in the middle. Especially the needs of

persons in their second half of life, who have not

grown up in the course of digitalisation but who have

moderate digital skills, have received little attention

so far. Considering cohort effects, it can be assumed

that the proportion of the group with moderate digital

skills is especially high among people 50 plus, as

most of these people have gained their digital skills

more at work than in school or at home (Van Dijk and

Hacker, 2003). A part of this group, often referred to

as “Baby boomer generation”, could benefit from an

enormous economic growth and, considering that

they benefited significantly from a successful

expansion of education, was able to achieve good

employment opportunities (Höpflinger, 2019; Oertel,

2014). As general trends, technisation and

digititalisation were dominant in their later

professional phases. Therefore, it can be expected that

this large group has at least basic, if not in-depth

experience with technology and digitalisation

through their professional activity.

It is therefore very important to focus on this

group of people, aged 50 plus with moderate digital

skills. It remains questionable how this group is

supposed to develop its digital competences beyond

professional life. Although getting older adults online

has been a high priority in many countries, little

attention has been paid to whether and how their

usage can be sustained over time.

The assumption that once someone is online, he

or she will remain digitally engaged might not be true.

According to Olphert and Damodaran (2013), older

adults are more vulnerable to give up digital

engagement. The authors see this phenomenon as a

potential but largely unrecognised “fourth digital

divide” which has serious implications for social

inclusion. Especially when it comes to the post-

professional phase in the course of retirement, not just

training opportunities on the job, but also informal

learning opportunities decline since social networks

decrease. As a consequence, this group is at high risk

of being left behind digitally and strategies and

programmes should be developed to support the

further development of their digital skills, even

though it is recognised that courses do not completely

prevent people from giving up the Internet and

computers, because it may also be the case due to

changing needs and priorities. Based on findings of

SHARE data that showed that also previous online

older adults stop using the Internet, König and Seifert

(2020) recommend that possible interventions for

addressing those older adults in particular should be

promoted, such as skills training.

In order to meet the aforementioned social needs,

the project “Digital Skills and Training Needs of 50+.

A Study Beyond the Digital Divide”, funded by the

Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) within

the program NRP 77 “Digital Transformation” is

conducted with a strong focus on practical application

and implementation. The project is carried out from

2020 to 2024 by the Institute for Ageing Research

(IAF), OST – Eastern Switzerland University of

Applied Sciences. The project, its individual parts and

the methodological approach are presented in detail

below.

2 PROCEDURE

2.1 Project Goals

The core goal of the project is to analyze the digital skills

and training needs of people 50 plus and the current

course offers in this context. In addition,

recommendations for action are developed. The

research project is designed as a mixed-method study,

consisting of quantitative and qualitative as well as

primary and secondary research with a clear practical

implementation and applicability. Furthermore, the

project is not only used to generate cross-sectional

data, but also to create an infrastructure that allows to

generate sustainable long-term data during and

beyond the project.

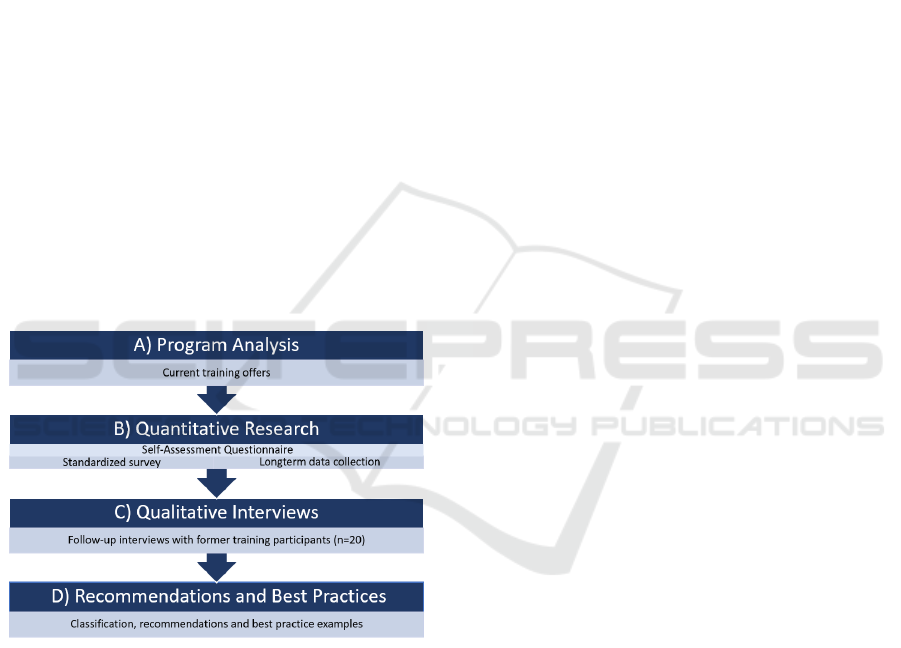

2.2 Work Steps

To meet the project goals, the following steps are

realized:

A) Providing a comprehensive analysis of current

training offers on digital skills for 50 plus throughout

Switzerland using the method of a program analysis.

B1) Compilation of a comprehensive questionnaire

for a representative, Switzerland-wide survey (in

German, French, Italian) to assess the actual digital

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

278

competences of Swiss people 50 plus, course

experiences, and influencing variables such as

sociodemographics, technology interest, self-

efficacy, etc.

B2) Developing a self-assessment (in German,

French, Italian) for people 50 plus, online available

and to be used beyond the project period to generate

long-term data on digital competences and

knowledge about cohort effects in Switzerland.

B3) Conducting a representative survey (including

B1, B2) of people 50 plus in Switzerland (n = 400).

C) In-depth analysis of training experiences with

courses for the acquisition and maintaining of digital

competences as well as future digital training needs

by interviewing people 50 plus (n = 20).

D) Formulation of specific, evidence-based

recommendations for stakeholders wishing to design

new training courses on digital competences for

people 50 plus and with different educational

backgrounds and experiences. The recommendations

will focus on the content, the didactical, and the

structural level. The recommendations will be

enriched with best practice examples in a factsheet.

The individual steps are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Procedure of the project.

2.3 Methods

A) Program Analysis: Current Training Offers

In part A of the study, an overview of the current

course offerings for older adults in Switzerland is

gained. With regard to contents, topics, methods used,

target groups, needed digital skills and gaps in

services the method of program analysis, an adult

educational method, focuses on the programmes as

the object of investigation. A programme expresses

the learning concept of an educational institution, its

understanding of education and qualification (see

Gieseke 2008; Gieseke and Opelt, 2003). At the same

time, it materializes the provider's ideas about the

educational needs of potential participants (Nolda,

2011). Therefore, programmes offered in 2020 and

2021 (online and offline) are identified as the

information source that will deliver the most relevant

data applicable for the project. The search is focused

on providers of non-academic adult education in all

parts of Switzerland and will mainly focus on the

online information portal of the Swiss authorities

(www.ch.ch), a service of the Confederation, the

cantons and the municipalities. The analysis follows

three steps (Käpplinger, 2008): a) Coding: The

programs will be systematically analysed according

to a coding system. The coding plan is developed

specifically for this study and will be orientated on

coding plans already tested in research (see Gieseke

and Opelt, 2003; Schrader and Zentner, 2010).

Categorisation is inductive and deductive. To

increase the reliability and quality of the results, an

intercoder-reliability check is carried out (Misoch,

2019). b) Data check: In case of ambiguities,

discrepancies are discussed in the research team, and

disputed cases will be documented. c) Analysis: The

program analysis of this study combines quantitative

and qualitative methods. The quantitative results will

be prepared in quantifiable form via SPSS 26.

Qualitative data will be interpreted under the use of

qualitative aspects using content analysis (Mayring,

2015) via Atlas.ti.

B) Quantitative Research on Digital Skills

B1) Compilation of a comprehensive questionnaire to

survey digital competences of Swiss older adults 50

plus, their experiences with courses concerning

digital skills, and a broad range of influencing

variables. The questionnaire includes questions about

sociogemographic variables (age, gender, nationality,

residence, education level, marital status, household

size, income, past and present occupation),

technology interest, self-efficacy, health status,

digital skills (see B2), experience with digital skills

courses, wishes and needs regarding digital training,

actual available digital support.

B2) Development of a self-assessment questionnaire.

The development process of the self-assessment

questionnaire includes several steps. Item generation

is based on the indicators of digital competence

formulated by the European Commission (2014) as

well as on the digital competence framework by the

European Commission (Ferrari et al., 2013) and

augmented by further literature on digital

competences and related already developed

Beyond the Digital Divide: Digital Skills and Training Needs of Persons 50+

279

measurement instruments. A first draft of the

assessment will be presented to and developed

together with an advisory board of the project,

consisting of course providers in Switzerland, with

the goal to gain consensus from the experts whether

the items reflect the characteristics required to

measure digital competences. The adapted

assessment is also presented to a group of older adults

of the Sounding Board of the IAF to gain feedback on

aspects like clarity and handling. A pretest with n ≥

60 refines the defined items. As often found in

research, a convenience sample for the pretest will be

used (Connelly, 2008; Mair and Whitten, 2000). The

participants for the pretest are recruited in a snowball

system via the established internal network of the

IAF. By conducting tests evaluating reliability (e. g.,

Cronbachs’s Alpha) it is ensured that the self-

assessment fulfils the quality requirements regarding

consistency and accuracy

B3) A representative telephone survey of people

aged 50 plus (n = 400), across the three Swiss

language-regions (German, French, Italian) is

conducted. Besides general demographic variables,

the survey contains the self-assessment questionnaire

on digital competences (see B2), and various

(standardized and open) questions on training

experiences and training needs (B1). One focus is on

the investigation of possible differences in

competences and needs among people with various

educational levels as well as on differences within age

groups, gender, and income. In addition, analyses are

carried out to examine the interaction between

competence levels and needs. The standardized

telephone survey will be conducted by a social

research institute using computer-assisted telephone

interviewing (CATI) that provides the research team

with the raw data, in the form of an anonymized SPSS

dataset. All further processing and evaluation steps

will be carried out by the research team of IAF.

Besides the analyse of cross-sectional data, this

project will be used to establish a sustainable

infrastructure to gather long-term data. The self-

assessment questionnaire will be available online in

German, French and Italian and will be promoted to

course providers across Switzerland. Potential course

participants will be able to follow a link, which leads

them from the course provider's website to the online

version of the self-assessment questionnaire

(embedded in the website of IAF). The interested

participants can click through the assessment and will

receive a summary of their digital competence level.

Course providers can begin to indicate what level of

competences the offered course addresses and they

can create courses based on the existing competence

levels. The data will be stored on the internal server

and continuously enrich the data set, that can be

analysed cross-sectionally and sequentially.

C) Qualitative Interviews: Training Experiences

and Needs

Qualitative telephone interviews are conducted with

a subgroup (n = 20) from the standardized survey

(B1). The semi-structured interviews (Misoch, 2019)

are planned six months after the quantitative survey

and will be used to learn more about the participants’

experiences with the courses: What expectations,

needs and motivations were linked to the course

participation? Did the course meet the initial

expectations? What positive and negative

experiences did the participants have with the course?

Did the participants feel adequately addressed by the

course? The results and conclusions will contribute to

developing recommendations for future courses.

D) Recommendations and Best Practice Examples

In the final part of the study, the results of the

previous steps will be combined, and

recommendations will be derivated and illustrated

with international best practice examples.

Additionally, the formulation of recommendations

will also consider research-based pedagogical

frameworks, such as “Universal Design for Learning”

(UDL) (e. g. Meyer, Rose, and Gordon, 2014) to

maximize learning for people 50 plus through the

three main pillars affective networks, recognition

networks, and strategic networks. A classification

that allows the evaluation of current training offers

will be developed, and best practice examples will be

recommended. The recommendation guideline will

be made accessible to all relevant stakeholders and

seek to improve and optimize the current training

offers for older adults, enhancing the digital

competences of people 50 plus on the long-term. The

selected best practice examples will be published

together with the recommendations as a factsheet.

Interested course providers can use the information in

the factsheet to learn from each other. The factsheet

aims to strengthen national and international

networking between course providers.

3 EXPECTED RESULTS

The program analysis (A) provides a comprehensive

survey and analysis of the current courses offered in

Switzerland for people 50 plus and will be the basis

for developing a grid of how courses are categorized

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

280

to create a fit between the captured digital skills (B2)

and provided courses.

With the compilation of the self-assessment

questionnaire (B2), it is intended to meet three

objectives: First, it will be the basis for and part of the

quantitative survey (B3) and provide information on

the current state of digital competences of persons 50

plus in Switzerland. Second, it can be used by training

providers and older adults to assess the digital

competence before the training (like the level tests

before language courses). Therefore, it is possible to

match training offers and digital competences in the

best possible way. Third, it will be made available to

course providers during and beyond the project. This

will make it possible to collect long-term data and

compare digital competences with each other in a

sequential design.

The project steps A to C aim to find out which

courses regarding digital skills are available, which

digital skills, training needs and expectations persons

50 plus have and whether previous courses could

meet these needs and expectations respectively what

could be improved.

The summary analysis and evaluation of the

project steps A, B, and C lay the foundation for a

classification for best practice recommendations (D).

The classification contains criteria which, according

to the project findings, are important and relevant for

the age group 50 plus in terms of ensuring the

acquisition of digital competences.

With the project, it is expected not only to

contribute to scientific discourse but also to create a

significant contribution to practice. By deriving

recommendations from the research results and

illustrating them with best practice examples, courses

for people with medium digital competences can be

developed or adapted. The self-assessment

questionnaire makes digital competences and

knowledge gaps visible to older adults and helps to

communicate training needs. It can be the starting

point for further course search or open up a

conversation with a course provider in order to find

the best matching offer. The data thus gathered

enables course providers to identify different target

groups and to tailor their offers accordingly. The

involvement of stakeholders in form of an advisory

board (course providers, older adults and other

experts in adult education) from the beginning of the

project ensures that the results are applicable in

practice and implemented into concrete and requested

course offerings even beyond the project. On the

long-term, the project contributes to ensuring the

lifelong acquisition of the required competences to

participate confidently in the digital world and

support the needs of social transformation. Findings

from this study should be applicable across various

age groups and may be applicable in other countries

besides Switzerland as well.

REFERENCES

Castells, M. (2002). The internet galaxy: Reflections on the

Internet, business, and society. Oxford: Oxford

University Press on Demand.

Connelly, L. M. (2008). Pilot studies. Medsurg Nursing,

17(6), 411-412.

DigComp (2020). DigComp. Digital competence

framework for citizens. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcomp

Eastin, M. S., Cicchirillo V., & Mabry, A. (2015).

Extending the digital divide conversation: Examining

the knowledge gap through media expectancies.

Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(3),

416-437. doi:10.1080/08838151.2015.1054994

European Commission (2018). DigComp project

background. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcomp/project-

background

European Commission (2014). Measuring digital skills

across the EU: EU wide indicators of digital

competence. Retrieved February 13, 2020, from

http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/cf/d

ae/document.cfm?doc_id=5406

Federal Statistical Office (2020). Szenarien zur

Bevölkerungsentwicklung der Schweiz und der

Kantone. 2020-2050. Neuchâtel: FSO.

Ferrari, A., Punie, Y., & Brečko, B. (2013). DigComp: A

framework for developing and understanding digital

competence in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications

Office. Retrieved April 02, 2020, from

https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstrea

m/JRC83167/lb-na-26035-enn.pdf

Friemel, T. N. (2016). The digital divide has grown old:

Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New

Media & Society, 18, 313-331.

Gieseke, W. (2008). Forschungsbefunde zum

Planungshandeln in der Weiterbildung–Programm und

Wissenserschließung, Handlungsmodellierung. HBV,

2, 126-135.

Gieseke, W., & Opelt, K. (2003). Erwachsenenbildung in

politischen Umbrüchen: Programmforschung

Volkshochschule Dresden 1945-1997. Wiesbaden:

Springer.

Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide:

differences in people’s online skills. First Monday,

7(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i4.942

Hargittai, E., & Dobranski, K. (2017). Old dogs, new clicks:

Digital inequality in skills and uses among older adults.

Canadian Journal of Communication, 42, 195-212.

doi:10.22230/cjc.2017v42n2a3176

Höpflinger, F. (2019). Wandel des dritten Lebensalters.

‚Junge Alte‘ im Aufbruch. Babyboom-Generation - zum

Beyond the Digital Divide: Digital Skills and Training Needs of Persons 50+

281

Altern einer Generation. Retrieved January 15, 2022,

from http://www.hoepflinger.com/fhtop/DrittesLebens

alter.pdf

Käpplinger, B. (2008). Programmanalysen und ihre

Bedeutung für pädagogische Forschung. Forum

Qualitative Sozialforschung, 9(1), Art. 37.

König, R., & Seifert, A. (2020). From online to offline and

vice versa: Change in Internet use in later life across

Europe. Frontiers in Sociology, 5(4).

doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.00004

Mair, F., & Whitten, P. (2000). Systematic review of

studies of patient satisfaction with telemedicine. BMJ,

320(7248), 1517-1520. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1517

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse.

Grundlagen und Techniken (12

th

, revised edition).

Weinheim: Beltz.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal

design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield:

CAST Professional Publishing.

Misoch, S. (2019). Qualitative Interviews (2

nd

, extended

edition). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Nolda, S. (2011). Programmanalyse–Methoden und

Forschungen. In R. Tippelt & A. von Hippel (Eds.),

Handbuch Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung (pp.

293-307). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Oertel, J. (2014). Baby Boomer und Generation X –

Charakteristika der etablierten Generationen. In M.

Klaffke (Ed.), Generationen-Management (pp. 27-56).

Wiesbaden: Springer.

Olphert, W., & Damodoran, L. (2013). Older people and

digital disengagement: A fourth digital divide?

Gerontology, 59(6), 564-570. doi:10.1159/000353630

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(2001). Understanding the digital divide. Paris: OECD.

Retrieved March 26, 2020, from http://www.oecd.org/

dataoecd/38/57/1888451.pdf

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On

the Horizon, MCB University Press, 9(5).

Schrader, J., & Zentner, U. (2010). Weiterbildung im

Wandel. Anbieterforschung im Längsschnitt am

Beispiel Bremen. DIE Zeitschrift für

Erwachsenenbildung, (1), 46-48

Schumacher, A., & Misoch, S. (2017). Nutzung von

digitalen Dienstleistungen von Menschen 65+.

Retrieved January 14, 2022, from

https://www.fhsg.ch/fileadmin/Dateiliste/3_forschung

_dienstleistung/kompetenzzentren/alter/Publikationen/

Nutzung_von_digitalen_DL.pdf

Selwyn, N. (2004). Reconsidering political and popular

understandings of the digital divide. New Media &

Society, 6(3), 341–362.

Stallmann, A. (2012). Silver Surver im Internet.

Information, Wissenschaft & Praxis, 63(4), 217-226.

doi:10.1515/iwp-2012-0046

Stern, M. J., Adams, A. E., & Elsasser, S. (2009). Digital

inequality and place: The effects of technological

diffusion on Internet proficiency and usage across rural,

suburban, and urban counties. Sociological Inquiry,

79(4), 391-417.

Tsai, H. S., Shillair, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2017). Social

support and "Playing Around": An examination of how

older adults acquire digital literacy with tablet

computers. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The

Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological

Society, 36(1), 29-55. doi:10.1177/0733464815609440

Tsekeris, C. (2018). Industry 4.0 and the digitalisation of

society: Curse or cure? Homo Virtualis, 1(1), 4-12.

doi:10.12681/homvir.18622

Van Deursen, A. J., Helsper, E. J., Eynon, R. (2016).

Development and validation of the Internet Skills Scale

(ISS). Information, Communication & Society, 19(6),

804-823.

Van Dijk, J. A. (2005). The deepening divide: Inequality in

the information society. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Van Dijk, J., & Hacker, K. (2003). The digital divide as a

complex and dynamic phenomenon. The Information

Society, 19, 315-326. doi:10.1080/01972240390227895

Vaupel, J., (2000). Setting the stage: A generation of

centenarians? The Washington Quarterly, 23(3), 197-

200.

Vervier, L., Zeissig, E.-M., Lidynia, C., and Ziefle, M.

(2017). Perceptions of digital footprints and the value

of privacy. In M. Ramachandran et al. (Eds.),

Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on

Internet of things, big data and ecurity (pp. 80-91).

Setúbal: SciTePress.

Wang, Q. E., Myers, M. D., & Sundaram, D. (2013). Digital

natives und digital immigrants. Entwicklung eines

Modells digitaler Gewandtheit. Wirtschaftsinformatik,

55, 409-420.

Wei, K. K., Teo, H. H., Chan, H. C., & Tan, B. C. Y. (2011).

Conceptualizing and testing a social cognitive model of

the digital divide. Information Systems Research, 22(1),

170-187. doi:10.1287/isre.1090.0273

Weibert, A., Aal, K., Unbehaun, D., & Wulff, V. (2017).

Geteilt vernetzt: Ausprägungen des Digital Divide

unter älteren Migrantinnen in Deutschland. Medien &

Altern, 11, 75-91.

ICT4AWE 2022 - 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

282