Game-based Events for School Community Mobilization

Victor Prado

a

, Carla Delgado

b

, Mônica Ferreira da Silva

c

,

Waldir Siqueira Moura

d

and Leandro Mendonça do Nascimento

e

PPGI, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, UNESA, PMDC, Brazil

leandromnascimento@gmail.com

Keywords: Technology, Games, School Community, Involvement, Tournament.

Abstract: Community involvement in school activities has long been the topic of studies, and while much has been

discussed in terms of its consequences and types of involvement, there is little research regarding events, as

a way to mobilize school communities in Brazil, especially game-based events. In light of Brazil’s poorly

perceived school environments as shown in 2018 PISA and the massive popularity of electronic games as a

hobby for Brazilian youth, this research will attempt to demonstrate how game-based school events can be an

effective way of involving school communities. This research followed a game-based city-wide project, which

occurred simultaneously in all schools of Maricá in Rio de Janeiro state, in Brazil, over the course of 2019.

While the project had many goals and activities, this article will aim on demonstrating the effects of its game-

based events in relation to school communities, as perceived by teachers and their students who participated

in the project.

1 INTRODUCTION

This research was based on Maricá-wide project,

named Ti-Games, which focused on using games in

all fifty schools of Maricá in the state of Rio de

Janeiro – Brazil, during the school year of 2019. The

project was composed of many game-based activities,

such as workshops, game tournaments and talks, and

was part of the city’s ongoing effort to build a game

development cluster. All fifty schools took part in the

activities, with more than 2500 students participating

directly, alongside approximately 400 school

teachers.

One of the main reasons for the research, is the

demand established by Brazil’s National Curriculum

guiding document – BNCC – for the use of technology

in schools beyond administrative use and how it states

the use of games to guide the learning process

(BNCC, 2018). Therefore, the main goal was to

examine Ti-Games impact on school community and

school routine, from the teacher and student’s

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3960-7195

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3570-4465

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0951-6612

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1545-7487

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6917-4274

perspective, in order to understand if using games, in

a legitimate manner – by the institution, can help

mobilize the school community in a positive manner,

around this hobby and related activities.

This research aims to demonstrate the

encouraging involvement of school community on

said project and how students who participated, were

positively surprised to see the city, their school and

teachers supporting their participation on a

videogame tournament. The research will also show

how teachers directly involved, perceived the

participation of their students and community in this

project.

1.1 Terms and Definitions

The project here researched, Ti-Games, consisted of

numerous game-based activities, which included a

game tournament within every school and between

schools. However, while electronic game

tournaments are popular and already common, this

638

Prado, V., Delgado, C., Ferreira da Silva, M., Moura, W. and Mendonça do Nascimento, L.

Game-based Events for School Community Mobilization.

DOI: 10.5220/0011079100003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 2, pages 638-645

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

specific tournament had a different format, one

created for the goals of the project which in essence

are contrary to what usual competitions aim for - to

measure and rank the skills of participants. Hence,

when referring to the tournament, we are precisely

talking about Ti-Games tournament, which had no

intention of measuring how able students were in any

specific skill or game.

This research shall use the term “game” as

referring to electronic games of entertainment not

related to gambling, as it is commonly understood as

in Brazil. The research shall also use the term

“gamer” as those who play electronic games, for it is

also understood this way in Brazil and it is also how

the English dictionary Merriam-Webster defines such

term. When mentioning “game-based activities”, this

research is referring to activities that either use

electronic games or are about electronic games, such

as workshops centered on creating or explaining

aspects of game development and industry.

While the goal of this research is the observe if games

used in schools by the institution themselves can

result in a positive mobilization of the school

community, one of the goals of the project Ti-Games,

was to legitimize game use in schools. With

“legitimate”, the present research means ways in

which games, including commercial titles, can be used

by the school itself with its students and faculty. With

“school community”, this research means all those

involved, directly or indirectly, with school activities,

although, focusing mainly on students, teachers, and

student’s parents. As it will be explained, data was

collected from students and teachers, as this

relationship can be seen as the base from which other

relations derive in regard to school.

1.2 Necessary Study Delimitation

The project here researched, Ti-Games, had a series of

game-based activities in schools, aiming for the

legitimacy of its use by the institution, however, this

article focuses on how and if games can used as a tool

to mobilize school community, especially students

and teachers in relation to a common activity.

Therefore, the following segments will briefly

describe the Ti-Games project, having a greater focus

on the activities held for school community

involvement such as the second phase of the

tournament, where schools competed against schools.

It is important to note, that Ti-Games project was a

public initiative, and all events were free for those

involved and no school, student, family, or faculty

was obliged to participate.

This research will not focus extensively on forms

or impacts of parent active participation on school

affairs, since this is widely researched and

documented. This research, will instead, focus on

parent and teacher active participation via school

internal and external events, related to the project, Ti-

Games, which consisted of several game activities,

though with its core, being a School versus School

game tournament.

2 BRAZIL’S SCHOOL

ENVIRONMENT AND

NECESSARY CHANGE

In 2012, Brazil’s school dropout rate, according to

United Nations Development Program (UNDP), was

the third highest between countries researched, and

by 2019, Brazil national research, PNAD (2013),

indicated that more than half of people older than 25

years old, did not complete their basic education and

at least 29% of those who abandoned school, were

drive by lack of interest. Dropout rate continued to

rise in Brazil, with an increase in 171%, according to

2021 research by Todos Pela Educação. While there

are many reasons for abandoning school, the 2018

PISA indicated that Brazil school environment, as

perceived by students is place of loneliness, bullying

and indiscipline, one that did little effort to embrace

students (G1, 2018).

On average across OECD countries, 21% of

students had skipped a day of school and 48% of

students had arrived late for school in the two weeks

prior to the PISA test. In Brazil, 50% of students had

skipped a day of school and 44% of students had

arrived late for school during that period. In most

countries and economies, frequently bullied students

were more likely to have skipped school, whereas

students who valued school, enjoyed a better

disciplinary climate, and received greater emotional

support from parents were less likely to have skipped

school (OCDE, 2018).

The report also stated that 41% of the student’s

recognized indiscipline, 23% felt lonely in school and

13% self-declared feeling sad. PISA also stated that

improving school environment for students, is a

possible solution to help revert this scenario (OCDE,

2018), this is further corroborated by Brazilian

research on school indiscipline (Garcia, 1999), which

suggests that improving school image and

atmosphere, for students and parents, may help

generate school spirit, and the sense of belonging for

students, consequently creating a welcoming

environment.

Game-based Events for School Community Mobilization

639

2.1 The Need for School Community

Active Involvement

Discussions surrounding the needs, forms and

impacts of family involvement in school have largely

concluded that active family interest and participation

in school activities have positive results regarding

student achievement (Herman et. al, 1983). Studies

suggest that school endorsed events are effective

ways of involving and stimulating connectedness

with parents (Dove et. al, 2018).

School events offer ways to work with specific

student’s areas of interest, such as sports and arts,

stimulating further parent and student non-

compulsory participation. The planned structure of

events, which usually defines and limits, timewise,

ways for parent contribution and relevance, may also

explain why this type of official school activity is

effective in promoting involvement - as lack of

planning and mutual understanding, between school

and parents, are seen as the greatest barriers. (Cotton

et. al, 1989).

2.2 A Generation of Gamers

To understand the role of games as a tool for

mobilizing school community, it is imperative to

discuss today’s generation of students. According to

Prensky (2001), one of the main advocates for game

use in education and the need to adapt educational

systems for today’s generations, there is a disparity in

language between teachers – whom he sees as “digital

immigrants” and students – “digital natives”. For

Prensky, “digital natives” were born in a world with

digital interfaces, while “digital immigrants” saw the

development of these inventions, a difference that

leads to a gap in communication and perception of

new technological tools.

This discrepancy in communication between

students and teachers, is one of the main reasons why

many traditional schools, such as Brazil’s public

schools, feel dissonant with today’s technological era.

When considering there were 75,7 million gamers in

Brazil in 2019 (pacete, 2019) and 162 million internet

users, with a 75.7% technological penetration rate

regarding smartphones and internet (statista, 2021), it

is safe to suppose that most students are indeed

gamers. In this regard, game-based events may be a

viable option for schools, not only due to the

ubiquitous and accessible nature of this hobby, but the

value it may provide in adjusting school

environments to today’s youth reality.

2.3 Games and Social Connectivity

Philosopher Johan Huizinga (Homo, 1938) one of the

most cited game researchers, believed playing and

games can promote social grouping, and while

historically, games have been a part of human culture,

this notion recently reached headlines during the

Covid-19 pandemic, as the World Health

Organization recommended playing online games to

withstand social isolation. The ubiquitous and

cultural nature of games, along with the social

stimuli, during times of social isolation, may aid

explaining the recent steady increase in gamers aged

above fifty.

Other researchers, such as Jane McGonigal, had

previously indicated the social strengthening aspect

of games and how playing together may generate a

cooperative spirit, something that has been

thoroughly discussed in relation to group sports,

many of which are in fact games (Kamau, 2015).

However, one major issue with physical games,

considered sports, have always been the physical

demands and usual segregation of participants, based

on age, gender and weight, for the purpose of game

balance (Nixon, 2007) and while this offers a fairer

activity, it does limit the socialization potential of

games. In comparison, electronic games are more

physically accessible and can offer a more democratic

and inclusive group activity, reducing possible

differences between those playing together, this is

seen in electronic sports competitions, “e-sports”,

where there are usually no gender, age or weight

divisions. This was also seen in Ti-Games project,

and while it involved many game-based activities,

including competitions, it was not an electronic sport

competition, as stated here before.

3 PROJECT EXECUTION

Ti-Games project had as one of its goals, to

implement the legitimate use of games in schools, by

the schools themselves, recognizing gaming culture

and stimulating new practices with games as an

educational tool. For this reason, the school versus

school tournament that took place in the second half

of the project, had no intention of being a real skill-

based competition, and instead, was focused on

promoting school spirit and involvement on a

common game-based event happening in all schools

of the city.

As mentioned before, the project had other game

centered activities such as workshops and talks for

students and teachers alike, however, this research

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

640

shall describe events that were focused on involving

the whole school community.

In short, the project started with game centered

activities in all fifty schools of the city, offering talks

about the game industry and its professions,

workshops of game design and design thinking with

games, as well as a smaller tournament within each

school, to establish a school team for the second

phase of Ti-Games. These activities took place in

each school and were limited to fifty students, gamers

between the ages of 12 and 18. There was no limit of

participation for the faculty focused activities,

however, at least one school director was required to

be present, this legitimized the participation of the

school, as it signaled to its community that school

direction was onboard, this had positive effects as the

research will demonstrate. All schools received the

exact same activities and for the same number of

students, however, schools were encouraged to

organize their own game centered events, such as

team practice for the tournament, while waiting for

Ti-Games second phase. While this research did not

record such events, these were incentivized by the

project organization, as it was aligned with Ti-Games

goal of legitimizing games in school and stimulating

game culture.

When all fifty schools had received their Ti-

Games activities and consequently formed a school

team, the project advanced to the second phase, a

school versus school game tournament. On this phase,

schools had to participate with their teams on a

minimum of rounds to accumulate points and advance

towards the semifinals. These rounds were events

hosted after school hours, by schools that offered to

host, as well as some that were hosted in public

gymnasiums.

While not disclosed to students, points were

mainly awarded for collective effort made by each

school community, such as, being present in all

rounds, cheering for their team, helping other school

teams reach their designated rounds and online

support on social media; points for winning the game

contest on each round were only relevant as a

criterion for tiebreaking.

Over the first phase of Ti-Games, 2500 students

participated in the activities held within each of the

fifty schools of the city, out of which, ten students per

school managed to form the school team for the

second phase of the project. Any student of the school

could substitute for the school team, so having an

official team formed by ten students, was a mere

formality to bolster the moral of those students who

were more engaged in the first phase.

Since, mastery of specific games was not the

intention of the project, the tournament had a unique

format, with games not being announced until the day

of each round and with the organization behind the

tournament, reserving the rights of changing game

titles mid rounds, in case students had previously

played them. Every round, three games were

announced from amongst a pool of preselected

games, all of which were age and school appropriate

and were curated with the project’s goals in mind,

teams had to play all three games and for the same

number of times.

Teams that managed to win more matches in each

round, were awarded slightly more points, this

however, was not disclosed for students as not to deter

their personal efforts.

During this phase of the Ti-Games project, many

rounds were offered for schools to accommodate their

calendar and avoid eliminating teams due to being

unable to participate on a specific day. For safety

reasons, only schools that confirmed attendance

could participate on these events, since most were

held within school grounds, however, there were

three open to public events, held in public

gymnasiums, that had different themes but were all

centered on further school community involvement,

these shall be described later.

Participation and attendance rewarded more

points than winning each round and to further

accommodate schools, teams could call in any student

at the school as a reserve in case the official team

could not attend. This rule also intended on including

all students on the responsibility of attending events

and eliminating any possible blaming. Parents were

asked by schools to take turns in taking teams to these

events, but many schoolteachers also took up the task

voluntarily and outside work hours, something that

was unexpected.

Aside semifinals and finals, there were three other

open to public events, all designed to involve those

beyond direct participation. Attending these events as

a school awarded extra points, but again, there were

no punitive measures incase teams could not

participate, especially since they were held during

weekends. One such event, was completely centered

on activities for student’s families, with workshops

and tournaments focused on parents and students.

The goal of these events was to allow involvement

and support of those close to students participating of

Ti-Games, such as neighbours, older brothers,

parents, and family friends. All three events had a

surprisingly high participation of family and friends

outside of school direct relations, however, this was

only observed and not measured quantitatively, as to

avoid any discomfort by those attending. The number

Game-based Events for School Community Mobilization

641

of teachers present on these three events was also

unexpectedly high, while many were directly

involved in the competition, their school received no

extra points for having faculty present and many of

those who participated, were in fact, with their family

which in many cases were not students at the schools

they worked in.

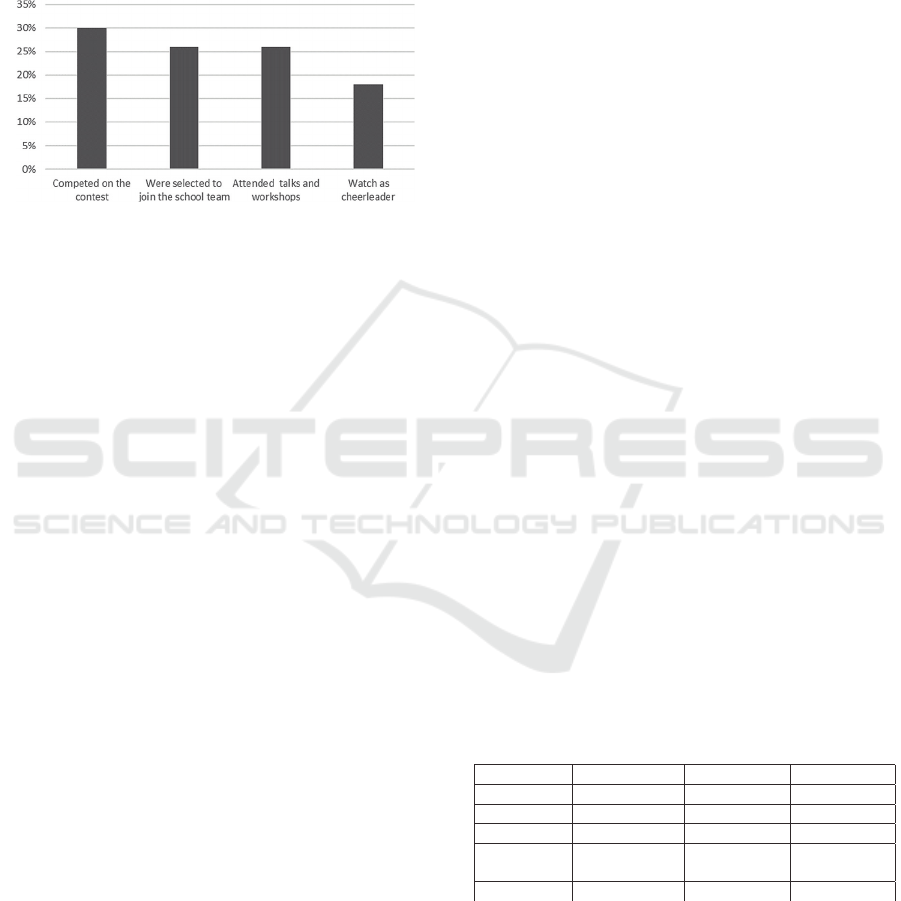

Source: research data

Graph 1: How students were involved with Ti-Games.

The semi-finals and finals were also open to

public events that took place in a public gymnasium

and during Saturday and Sunday, respectively.

Schools who accrued a minimum of points –

something undisclosed for schools but was met with

the minimum participation - during the second phase,

were able to participate in the semi-finals. For this

decisive round, a normal tournament format was

presented and advancement towards the finals was

mainly based on winning matches. The finals

happened the following day and counted with other

activities prior to the matches, to further stimulate

participation of schools who weren’t competing

anymore. Since this phase of the project was centered

on school community effort and involvement, the

main prize was a “gaming room” for the school and a

plaque containing the team’s names - this was

awarded to first and second place, as to further

diminish the competitive aspect of the project.

Data was collected via questionnaires (Appendix

A) from students and teachers (Appendix B) that

participated in the project, up to the semi-finals and

finals, collection was done during these two days,

with the goal to measure the project’s impact on those

who were engaged to the very end. Answering the

questionnaire was voluntary and the intention was to

note how these students and teachers perceived the

project and its impacts on themselves and on their

communities, which could lead to a better

understanding of the overall relationship of those

involved with their communities.

While semi-finals and finals were open public

events, and there were students present who did not

partake on the tournament directly, or participated

indirectly cheering for their school team, these

students did not receive questionnaires to answer. On

the same note, only teachers who accompanied teams

and were involved in previous activities of the project

were handed questionnaires to answer, although

regarding teacher’s results, there were less answers

than what was expected.

3.1 Analysis of Results

Research found that 59% of students had already

imagined themselves participating in game

tournaments, however, it is important to note that

these students wre those who participated the most,

and therefore, can be speculated that they had greater

propensity in seeing themselves in this reality. In

contrast, 81% of the students who answered, claimed

they had never imagined their school encouraging

their participation on a game tournament, a result that

when considering Pisa report (2018), regarding

school environment in Brazil, may indicate low

expectations, on behalf of students, towards their

school. This can be further corroborated with

teacher’s data collected, 54% stated having noted a

greater interest in school by their students, during Ti-

Games project. This may be aligned with what was

suggested as school image improvement for students,

in the research regarding Indiscipline in Brazilian

Schools (Garcia, 1999).

Results of both, students, and teachers, appear to

indicate effort from both ends towards participating

in the project, with 71% of students claiming they

were encouraged to participate by teachers. At the

same time, teachers were asked how their students

were involved in the project, if they were involved at

all, and unsurprisingly, all claimed their students were

involved in some way and with similar distribution in

relation to how they were involved, as show in graph

1.

Table 1: Who else in your school community was involved

with Ti-Games.

Little involvement

P

artial involvemen

t

A

lot of involveme

n

Students 0% 14% 86%

Teachers 14% 29% 57%

School Sta

ff

14% 14% 72%

School

Directors

0% 28% 72%

Parents and 14% 36% 50%

Teacher results further indicate school community

mobilization, for 64% of teachers perceived an

impact on school routine during Ti-Games, with only

7% claiming they noticed no change. Out of those

who claimed having perceived said impact, 86%

stated the impact was of positive nature. While the

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

642

whole project did involve all schools in the city, with

more than 300 activities in total, most of these

activities were done in the first phase, with each

school receiving the same events for the same number

of students. This is noteworthy, as it might indicate

that schools may have kept internal game events,

unrelated to those of Ti-Games, such as school team

practice or other game centered events, in preparation

or in inspiration with the project.

This may be further suggested from students

answers regarding what they appreciated the most

from the whole project, with 61% expressing they

enjoyed knowing their city of Maricá was focusing on

game development. Another research, published in

2021, concluded the project had a positive impact in

improving students’ confidence in their professional

perspectives in the game industry (Prado, Victor, et

al. 2020) when related to this research’s analyses, this

could indicate the project’s success of starting a game

development cluster in Maricá, as it reveals student’s

perception of their community and city movement, as

a whole. Positive social impact may be further

deduced from the results of the same question in hand,

with 18% of students indicating that what they

enjoyed the most of Ti-Games, was making friends.

It is interesting to note the disparity between the most

picked answer and the second, which while both are

positive, could suggest that mobilizing the city in

favor of their interest may come prior to new

relations, even if this may be one of the goals of such

endeavour.

Due to ethical reasons and time constraints, there

was no data collected from parents or family,

however, as stated before, while school community

involves many relations, this research focused mainly

on student and teacher relation and their perspectives,

as most relations within the school community, derive

from this focal point. In this sense, teachers were

asked how they perceived their school community

involvement with the project over the year.

Unexpectedly, teachers perceived involvement of

other teachers was barely above 50%, which could

indicate a critical view of their colleagues, after all,

they were the ones accompanying their school’s team.

On the other hand, 86% claimed their students were

really involved with the project, which can

corroborate student’s claims over being encouraged

by their teachers and suggest a cooperation towards a

common goal. Two results, however, require further

consideration when analyzing towards answering this

research’s question, one being school director

involvement and the other regarding neighbours’

involvement. In relation to school director, 72%

claimed having perceived their participation, though

it was required that every school had at least, one

school director directly involved in activities, which

could indicate a non-voluntary participation. In

relation to neighbours, they were the least involved as

perceived by teachers, although it is worth

considering who they considered neighbours, as 50%

of teachers perceived a lot of parent’s involvement.

Figure 1: National and local media coverage. Source: For

Games (2022).

4 CONCLUSION

Ti-Games project involved all fifty schools of the city

of Maricá, over one school year, with 2500 students

and 400 teachers directly involved and many involved

indirectly, this social mobilization can be seen in

media coverage of the project as shown in figure 1.

School community participation during and after

school hours was fundamental for the project to take

place, as schools had to work to fit activities in their

schedule and many even hosted events for other

schools. Teams also had to be taken and supervised

by adults during external events, some of which took

place during weekends and holidays, factors which

did not deter the efforts of many teachers and can

indicate a sense of school spirit and representation

around some communities. This sense of school

representation could also be seen in the efforts of

schools, to mobilize students to cheer and support

their team during events, this is seen in graph 01, as

18% mentioned perceiving students participating by

watching and cheering for their team.

Nevertheless, due to limited resources and ethical

reasons, data was not extensively or directly collected

from the school community, which limits this

research to document the positive mobilization of the

school community, from teacher’s and student’s

perspective. As stated, teachers perceived greater

interest in school from their students during Ti-

Games and at the same time, students were surprised

to see their school encouraging their participation,

Game-based Events for School Community Mobilization

643

which could indicate a positive view of their school,

especially when considering students extensive

efforts for a competition with no individual prize.

This betterment of school image for students, as well

as the clear effort of the community involved, can

further corroborate studies suggesting that school image

improvement for students has a positive impact, as well as

studies indicating the positive

impact of parent’s

participation. It is worth noting results of study

aforementioned, which stated that students who

participated, displayed confidence in their chances of

winning future competitions, this could reinforce the

suggestion of family participation in school activities

having a positive impact in student achievement.

It is important to reenforce the fact that Ti-Games

was a public project, free of charge for participation

and that approximately half of the schools involved

were public, meaning that many schools were private.

At first, it was generally expected that private schools

would have an advantage, since transportation,

equipment for practice and general support for teams

could be provided by schools, this however, was not

the case, and public schools had better results in the

long run, including winning first and second place.

While this research did not extensively measure the

effects or nature of school community involvement, it

is clear, that there was a positive contribution of each

community. This indicates a possible direction for

future studies, thoroughly investigating the nature and

extent of the impact of such event, in different school

communities. Another future study could be on the

quantitative effects of school community

involvement, in relation to their team’s success, in

similar game tournament events, to better understand

the relevance and consequence of this support.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum

Curricular. Brasília: MEC, 2018. Available in

http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_

EI_EF_110518_versão final_site.pdf. Accessed on

April 17, 2019.

Cotton, Kathleen, and Karen Reed Wikelund. "Parent

involvement in education." School improvement

research series 6.3 (1989): 17-23.

Dove, Meghan K., Jennifer Zorotovich, and Katy Gregg.

"School community connectedness and family

participation at school." World Journal of Education

8.1 (2018): 49.

Garcia, Joe. "Indisciplina na escola: uma reflexão sobre a

dimensão preventiva." Revista Paranaense de

desenvolvimento 95 (1999): 101-108.

___. Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how

they can change the world. London: Penguin, 2011.

___. SuperBetter: a revolutionary approach to getting

stronger, happier, braver and more resilient. London:

Penguin, 2015.

G1, 2018. https://g1.globo.com/educacao/noticia/2019/12

/04/bullying-indisciplina-e-solidao-o-clima-nas-escola

s- brasileiras-reveladas-pelo-pisa-2018.ghtml

Herman, Joan L., and Jennie P. Yeh. "Some effects of

parent involvement in schools." The Urban Review

15.1 (1983): 11-17.

Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens. 10. Ed. São Paulo: Editora

Perspectiva, 2020.

Huizinga, Johan - Homo Ludens,published by H. D.

TjeenkWillink& Zoon, 1938.

Kamau, A. W., et al. "The effect of participation in

competitive sports on school connectedness of second-

dary school students." African Journal for Physical

Health Education, Recreation and Dance 21.3.1

(2015): 877-890.

Mcgonigal, Jane - SuperBetter: A Revolutionary Approach

to Getting Stronger, Happier, Braver and More

Resilient--Powered by the Science of Games. 2015.

Merriam-Webster English Dictionary accessed online at

https://www.merriam-webster.com/

NEWZOO – Brazil game market 2018. Available in

https://newzoo.com/insights/infographics/brazil-

games-market-2018/

Nixon, Howard L. "Constructing diverse sports

opportunities for people with disabilities." Journal of

Sport and Social Issues 31.4 (2007): 417-433.

Pew Research Center - Gaming and gamers report 2015.

Available in: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/

2015/12/15/ga ming-and-gamers/

PNAD, 2013. https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia

-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/28

285-pnad-educacao-2019-mais-da-metade-das-pessoas-

de-25-anos-ou-mais-nao-completaram-o-ensino-medio#

:~:text=A%20pesquisa%20est%C3%A1%20divulgando

%20pela,7%25%20eram%20pretos%20ou%20pardos

Pomohaci, Marcel, and Ioan Sabin Sopa. "Extracurricular

sport activities and their importance in children socia-

lization and integration process." Scientific Bulletin-

Nicolae Balcescu Land Forces Academy 22.1(2017):46-59

Prado, Victor, et al. "A study with all schools in the city of

Maricá during a complete academic year using games

to increase students’ confidence in their professional

possibilities in the games industry."

Prensky, Mark – Digital Natives and digital immigrants.

2001 published in: On the Horizon NCB University

Press Vol. 9 No. 5.

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)

2018 report.

Salen, Katie and Erick Zimmerman - Rules of Play

published by Edgard Blucher Ltda,2003.

Statista – Internet usage in Brazil. Available in: https://

www.statista.com/topics/2045/internet-usage-in-brazil/

Ti-gamess. Available in https://www.forgames.biz

United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 2012

(UOL, 2013)

Weforum – World Risks Report. Cologny/Geneva,

Switzerland, 2021. Available in www.weforum.org

CSEDU 2022 - 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

644

APPENDIX

Appendix A – Teacher’s Questionnaire

Appendix B – Student’s Questionnaire

Game-based Events for School Community Mobilization

645