Assessing Informal Trails Impacts and Fragmentation Effects on

Protected Areas using Volunteered Geographic Information

Luís Monteiro

a

and Pedro Cabral

b

NOVA Information Management School (NOVA IMS), Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Campus de Campolide,

1070-312 Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords: Recreation Ecology, Informal Trail, Landscape Fragmentation, Recreation Impacts, Volunteered Geographic

Information.

Abstract: Informal trails represent an important visitor-related impact on the natural resources of recreational and pro-

tected areas by compacting soil, changing vegetation composition, moving wildlife, altering the hydrological

cycle, and fragmenting landscapes. This paper develops an approach to assess the extent of the informal trails

network and their trail-based impacts in a protected area within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. A

total of 28.911,254 km of Volunteered Geographic Information tracks were collected from a fitness and travel

web platform. Spatial analysis was performed to assess the extent of the informal infrastructure, and landscape

metrics were used to understand the diversity of trail-based fragmentation across the area. A total of 669,6

km were mapped as potential informal trails, hiking being the most popular activity using this infrastructure.

Approximately 58% of higher protection areas have been fragmented by informal trails development, repre-

senting a loss in the size and integrity of endangered habitat. The proposed approach allowed to produce a

significant coverage of information about the levels of impact from informal trails at the landscape scale using

a minimal amount of resources. Further work is recommended to validate results at the local scale using onsite

trail-based assessments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, many were

concerned about the challenges relating to the

management of overtourism in designated sites, and

the increasing numbers of users engaging in outdoor

activities in recreational and Protected Areas (PAs)

(Atzori, 2020).

With the pandemic, many changes appeared at the

society and individual level, and the outbreak showed

again the importance of nature as a valuable asset for

people to engage in outdoor activities when

opportunities are limited and during stressful times

(Jackson et al., 2021). During this period, as a result

of the multiple instituted shutdowns orders, visitation

levels reported worldwide registered a decline,

especially in urban forest recreation sites where

access was restricted, or in PAs located outside

Metropolitan Areas, and overseas destinations due to

restrictions on traveling (de Bie and Rose, 2021). In

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6594-7885

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8622-6008

contrast, urban recreational and PAs that remained

open and accessible continued to experience

considerable levels of visitation, similar to the period

of pre-COVID (Volenec et al, 2021).

An important reason for the high demand of

visitors to touristic and recreational sites is the

increased use of social media and the availability of

volunteered geographic information (VGI) at specific

websites (Chua et al., 2016; Goodchild, 2007). This

is a consequence of the democratization of the

technology, including the Global Positioning System

(GPS) on mobile phones (Burke et al., 2006) and the

increasing popularity of using applications to choose

where and how to travel based on recommendations

within social media networks and the trend to

consume, create and share experiences on social

media (Dickinson, Hibbert and Filimonau, 2016;

Wang et al., 2014).

As a consequence of the reported numbers of

users engaging in outdoor activities, that are often

48

Monteiro, L. and Cabral, P.

Assessing Informal Trails Impacts and Fragmentation Effects on Protected Areas using Volunteered Geographic Information.

DOI: 10.5220/0011088700003185

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management (GISTAM 2022), pages 48-55

ISBN: 978-989-758-571-5; ISSN: 2184-500X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

dependent on natural environments for their

performance, significant impacts can appear in those

areas that need to be assessed and managed. These

impacts can carry several consequences, affecting

ecosystem components; through the degradation of

the soil, vegetation, water, and wildlife resources

(Leung and Marion, 2000). This is particularly

important on trail networks where recreational

activities are performed most of the time (Marion and

Leung, 2001).

Formal trail networks are important strategies to

minimize recreationist impacts by concentrating use

on appropriate walking surfaces (Marion and Leung,

2004). However, when these networks fail to provide

the desired access and match the users´ experiences,

often users tend to venture off-trail, leading to the

creation of informal trails due to foot trampling

(Wimpey and Marion, 2010). This type of impact can

affect ecosystem components through the removal of

vegetation, displacement of wildlife, alteration of

hydrology, the spread of invasive species, and can

also exacerbate ecological fragmentation effects in

relatively undisturbed habitats (Walden-Schreiner et

al, 2012; Wimpey and Marion, 2010).

Although informal trails are present in nearly all

recreational areas and PAs, research focused on

informal trail networks remains minimal. This may be

due to the fact, that these user-created impacts are

often materialized in numerous, short, and frequently

segments arranged in complex patterns, making them

difficult to assess (Leung and Marion, 1999).

Through the years, informal trails mapping and

monitoring were commonly performed by using

hand-held GPS units and covering the entire trail

system networks of a site by walking (Wimpey and

Marion, 2011). Since limited human and financial

resources are often a major constraint, this technique

is many times considered costly in terms of time and

resources invested (Muhar, Arnberger and

Brandenburg, 2002).

However, recently there is a growing interest in

the use of new sources of data, such as VGI, to

understand the spatial and temporal patterns of

visitors' movements (Heikinheimo et al., 2017;

Walden-Schreiner et al., 2018b; Wood et al., 2013).

Among them, georeferenced tracks of users' routes

from fitness and travel websites and apps are one of

the most common components of VGI, as they

provide information regarding the type of activity and

related spatial and temporal aspects (Levin, Lechner

and Brown, 2017; Orsi and Geneletti, 2013; Sessions

et al., 2016). As this large number of VGI is many

times available freely to the public, these data can

also be used to reflect the spatial distribution of

recreational use in informal trails, by comparing it

with the existent formal infrastructures. Although,

despite the apparent limitations on data quality and

availability among sites, this type of information

allows to make an assessment of the extent of the

potential informal trail network within a recreational

area in an effective, cheap, and accurate way

(Norman and Pickering, 2017).

This paper presents a new approach that assesses

how informal trails development can contribute to the

fragmentation of recreational and PAs. Specifically,

it will assess an informal trails network using

geographic information systems (GIS) and VGI

obtained from GPS routes from a fitness and travel

platform to evaluate the lineal extent and variety of

informal trails on the area, examine the spatial

distribution of informal trails, and calculate the level

of landscape fragmentation using appropriated

metrics.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study Area

The proposed methodological approach was applied

in the Arrábida Nature Park (PNAr), an important

touristic and recreational destination located within

Sesimbra, Azeitão, and Setúbal municipalities in

Lisbon Metropolitan Area, which contains

approximately 2,8 M inhabitants (Figure 1). Created

in 1976 and being part of the National Network of

Protected Areas, the PNAr has approximately 17.500

ha, including 5.200 of marine, and a maximum

altitude of 501 m. It is dominated by one of the most

original and interesting types of landscape in the

country, with a wide variety of high-value ecosystems

that were included in the Natura 2000 Network.

Figure 1: Location of Arrábida Nature Park in Portugal.

Assessing Informal Trails Impacts and Fragmentation Effects on Protected Areas using Volunteered Geographic Information

49

2.2 Methodology

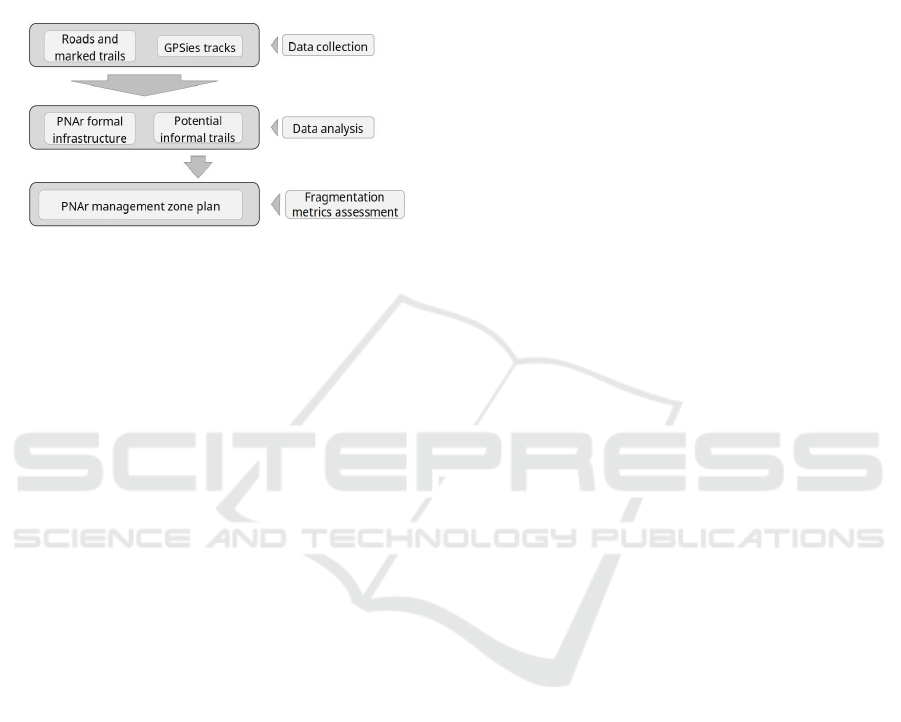

The methodology was structured into three main

phases: data collection from the Wikiloc.com

website; spatial analysis of GPS routes using a GIS;

and assessment of trail-based fragmentation using

spatial metrics (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the methodological

approach.

2.2.1 Data Collection

In order to characterize the spatial distribution of

visitor-created trails within the PNAr limits, the main

dataset was collected from the Wikiloc website

(Wikiloc, 2021), a crowdsourced online platform

containing GPS routes from visitors who wanted to

share their activities with others. For Europe, Wikiloc

has at the moment one of the best data coverages and

is considered to be suitable for off-trail use

assessment (Campelo and Mendes, 2016; Norman

and Pickering, 2017). The platform has operated since

2006, being one of the first fitness and travel

websites, with more than 28 M tracks (672.000 for

Portugal) and 9 M members by October 2021,

allowing tracking using all kinds of GNSS devices

and smartphones through dedicated applications for

Android and IOS devices.

Search queries on Wikiloc were conducted on

October 2021, using Setúbal, Sesimbra, and Palmela

municipalities as search criteria and considering 30

activities that are using trails for their performance.

Because Wikiloc limits the download to a few .gpx

tracks per user/day, VGI data were downloaded using

web scraping techniques.

In addition to the .gpx file, additional information

associated with the routes was collected, such as

author/user ID, URL of the track, route name/number,

user description, date posted, date recorded, type of

activity, route length, route type (linear or circular),

and downloads received.

2.2.2 Spatial Analysis of GPS Routes

Duplicated tracks and those with evident spatial

errors were eliminated unless the errors could be

fixed. Also, as Wikiloc allows users to draw routes,

these tracks were also excluded as they represent an

intention of use and not an actual recording. The

debugging process allowed create a clean shapefile

with the entire downloaded GPS track using QGIS

3.10 (QGIS), and the park boundary polygon was

used as a feature selection criteria for extracting the

routes that crossed or were within the PANr limits to

be used in the further analyses. One of the advantages

of using QGIS with .gpx files is that it converts

automatically the point data to line features without

the need to run any data management tools.

For extracting the potential informal trail

network, the official PNAr infrastructure (official

public road network and marked trails), including

official roads and trail network was considered as the

formal trail network. Moreover, in order to absorb the

spatial errors of bad GNSS reception under deficient

atmospheric conditions and canopy cover, a 30 m

buffer width of the formal PNAr infrastructure was

created. The considered buffer width followed a

similar procedure applied in the Campelo and Mendes

(2016) study, but as satellite reception is sometimes

reduced due to local characteristics of the area, the

buffer width is a bit higher than the 10 metres

employed by Korpilo et al., 2017 for example.

All tracks were then used and routes that

intersected each PNAr infrastructure were extracted

by selecting those that intersected the buffer

polygons, and those that did not (selection, dissolve,

and erase functions). The result was a shapefile

compiling all GPS tracks from activities that used the

formal roads and trail system and in opposite the

potential informal trails, that will be used in the

subsequent phase. The resulting trail networks were

intersected with the PA zonation plan to summarize

the linear extent of potential informal trails across

different management zones. Additionally, the

potential informal trails were also intersected with the

slope map, according to different landform grade

classes to understand if their development and spatial

disposition are related to this aspect.

2.2.3 Trail-based Fragmentation Assessment

To assess the landscape fragmentation within the

PNAr a method similar to Leung and Louie’s (2008)

and Wimpey and Marion (2011) was adopted. As

such, both networks were considered to analyse the

spatial impacts associated with the development of

GISTAM 2022 - 8th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

50

informal trails within the PNAr, and to calculate

different landscape metrics: Number of patches;

Mean Patch Size; Largest Patch Index; Mean

Perimeter: Area Ratio (Table 1). For the analysis, the

complementary and partial management

subcategories were merged into a single one of the

same patch type.

Table 1: Landscape metrics.

Number of Patches

(

NP

)

Description NP equals the number of patches of

the corres

p

ondin

g

p

atch t

yp

e

(

class

)

Units None

Range NP ≥ 1, without limit.

NP = 1 when the landscape contains

only 1 patch of the corresponding

p

atch t

yp

e.

Mean Patch Size

(

MPS

)

Description MPS is the average patch size in a

total class area

Units m²

Ran

g

e NP ≥ 0, without limit

Lar

g

est Patch Index

Description LPI equals the area (m²) of the largest

patch of the corresponding patch type

divided by total landscape area (m²),

multi

p

lied b

y

100.

Units Percenta

g

e

(

%

)

Range 0 < LPI ≤ 100

LPI is close to 0 when the largest

patch of the corresponding patch type

is increasingly small. LPI = 100 when

the entire landscape consists of a

single patch of the corresponding

patch type; meaning, the largest patch

com

p

rises 100% of the landsca

p

e.

Perimete

r

-Area Ratio

Description PAR equals the ratio of the patch

p

erimeter

(

m

)

to area

(

m²

)

.

Units None

Ran

g

e PAR ≥ 0, without limit.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Extent of Use among Formal and

Informal Infrastructure Networks

According to the considered search criteria, the final

dataset downloaded from Wikiloc consisted of 3.923

individual tracks, representing a total accumulated of

28.911,254 km, with 2195 tracks (4.509,545 km)

passing through the limits of the study area. This

dataset was uploaded into the platform between

March 2006 and October 2021 by 224 identified users

that participated with 3.635 tracks of the total dataset

downloaded and the remaining were anonymous.

Regarding the total length of use among each

network, a total of 3.839,414 km were considered

using the PNAr formal infrastructure and the

remaining 669,586 km configured potential informal

trails (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Spatial distribution of the formal infrastructure

and potential informal trails.

From the routes downloaded from Wikiloc, that

intersected the PNAr, 18% used the informal network

(partially or entirely), and there were 21 routes that

did not intersect a formal trail or road at any point. Of

the 395 routes of users who travelled partially or

entirely out of the formal infrastructure, 97 were

cycling activities, 189 hiking, and 66 running. Only

32 informal trails were used by motorized vehicles

and 11 routes recorded other activities (Table 2). A

reclassification of Wikiloc activities was necessary

following the mobility typology proposed by Callau,

Giné and Perez (2020).

Table 2: Number of GPS tracks posted according to each

type of activity along the formal and informal

infrastructure.

Activity On formal

infrastrcture

On informal

trails

C

y

clin

g

428 97

Hikin

g

977 189

Runnin

g

295 66

Motorize

d

311 32

Others 89 11

When plotting results against the PNAr

management zonation plan, 66% of the potential

informal network was developed on complementary

protection, 27% on partial protection, and the

remaining 7% on full protection (Figure 4). These

results represent all potential management conflicts

between current uses and each management zone.

Assessing Informal Trails Impacts and Fragmentation Effects on Protected Areas using Volunteered Geographic Information

51

Figure 4: Informal trails accrosss the Arrábida Nature Park

management zones.

3.2 Landscape Fragmentation in

Arrábida Nature Park

Landscape fragmentation metrics indexes were

calculated for both networks and are presented

according to the PNAr management zones. It is

possible to understand the rising in the number of

patches present for all zones between the

fragmentation when considering just the formal

infrastructure and when including the potential

informal trail network (Table 3). The Complementary

P. Zone has the highest number of patches (751), but

it was in the Partial P. Zone that showed the biggest

increase in the number of patches (+427,6%). As for

the Mean Patch Size, there was a decrease in all

management zones between the fragmentation of the

formal infrastructure and when considering also the

informal trails. The Total P. Zone is the management

zone that has the biggest numeric decrease in MPS

(84.006,13 m2), and the Partial P. has the largest

proportionally decrease (-58,65%). When comparing

values of the Largest Patch Index for the formal

infrastructure with results considering all networks,

they increased for the Partial P. and Total P. Zones,

while for the other management zones the Index

decreased. The Mean Perimeter Ratio increased for

all zones, with the biggest proportional (-126,7%)

increasing in the Urban Zone.

4 DISCUSSION

This work presents a methodology for assessing the

impacts of user-created trails and fragmentation

effects in the PNAr using VGI data from a platform

compiling georeferenced tracks from users.

As fitness and travel dedicated web sharing

services become more common, researchers and PA

managers are looking at these VGI components as an

alternative to generate information on the spatial and

temporal patterns of recreational use (Wong, Law and

Li, 2017). One of the main reasons evoked is the

capacity to generate preliminary results, that can

support other types of social studies, without a high

resource demand (Ghermandi and Sinclair, 2019).

The selection of Wikiloc for the assessment

allowed to answer the main goals of the study, and

generated significant data on the recreational use

within the PNAr, more particularly on off-trail use.

This agrees with other studies that obtain their

datasets from online services as a VGI source

(Campelo and Mendes, 2016; Norman et al., 2017).

Also, the number of GPS tracks downloaded (3.635)

can illustrate the popularity of the PNAr within the

Lisbon Metropolitan Area for nature-based tourism

and outdoor sports, with people (224 members/users)

sharing their activity on this platform. Platforms like

GPSies.com and Strava are also popular among

outdoor recreationists and could be an alternative for

this assessment. However, the former online service

was acquired by AllTrails.com, a less popular

platform in Europe, and the Strava dataset is not

easily available to the public.

The results also show that despite most users

preferring the official infrastructure, off-trail use is

still happening, leading to the creation and

proliferation of visitor-created informal trails.

Informal use was most observed close to local cities,

such as Azeitão, Palmela, and Setúbal, and also Cabo

Espichel. The proliferation of informal trails around

cities is many times a consequence of high levels of

use around these core areas, and the lack of an

appropriate formal infrastructure not matching users’

recreational needs and expectations. Off-trail use can

be particularly damaging in the promontory of Cabo

Espichel, as this area contains plant communities that

are sensitive to trampling and erosion impacts.

When compiling the amount of potential informal

trails by management zone to understand the extent

of impact in each zone, the fact that the

complementary protection zone accommodates the

greater linear extent of informal trails goes in line

with the degree of protection normally allowed at this

zone type. Complementary Protection Zones

integrate spaces of more intensive use of the soil,

where the social and economic local development

must be compatible with the natural and landscape

values in place. On the other side, the presence of

informal trails in full protection zone suggests a

potential management conflict as these are areas with

high ecological sensitivity, where recreational use is

GISTAM 2022 - 8th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

52

Table 3: Landscape fragmentation indices across the Arrábida Nature Park management zones.

Landscape metrics Mana

g

ement zones

Urban Com

p

lementar

y

P. Partial P. Total P. Overall

Number of patches

PNAr infrastructure 479 388 29 5 901

Informal trails 474 751 153 11 1389

Mean Patch Size

PNAr infrastructure 8.816,60 48.205,55 124.709,85 178.839,40 82.299,47

Informal trails 2.881,53 43.092,12 51.573,67 94.730,27 40.361,32

Largest Patch Index

PNAr infrastructure 0,87 6,55 3,33 0,71 6,55

Informal trails 0,15 6,26 4,67 1,03 6,26

Mean Perimeter Ratio

PNAr infrastructure 0,04 0,02 0,01 0,01 0,01

Informal trails 0,09 0,02 0,02 0,01 0,02

forbidden, representing a management issue for land

managers.

Lastly, the landscape fragmentation assessment

through the use of metrics on the management zone

plan allowed to examine the impacts of informal trails

development at the landscape scale. Just the impact of

roads and formal trails is significant on the MPS, but

when landscape fragmentation was assessed for the

formal infrastructure and potential informal trails

together all indices’ values decrease across zones.

5 CONCLUSION

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for the

practice of outdoor recreation activities in protected

areas continues to increase. Since many of these

activities are concentrated on trails, potential impacts

can appear in local environmental and social

conditions leading to a decrease in the quality of the

visitors’ experience.

Nowadays, research regarding informal trails

remains mainly absent, and there is a lack of a clear

and objective methodology to assess the impact of

user-created trails at the landscape level. To answer

these concerns, this study developed a method to

assess the impacts of informal trails in protected areas

using VGI georeferenced tracks stored in online

platforms.

The proposed procedures assessed the lineal

extent of informal trails within the PNAr and the

spatial distribution of user-created trails was

examined through analyses of management zones and

landscape fragmentation indices. These methods have

the advantage to complement other monitoring

studies in place (Mendes et al., 2012) allowing show-

case long-term trends of visitor use, related impacts,

or effectiveness of possible management and

maintenance actions.

The study highlighted different areas prone to be

impacted by off-track use, which represent valuable

information for the managers of that area when

prioritizing management decisions. These areas were

emphasized using the management zonation plan, and

the VGI revealed the extent of informal network

impacts in each park zone. Also, the fragmentation

indices calculated for PNAr produce a significant

coverage of information about the different levels of

impact from informal trails at the landscape scale

using a minimal amount of resources.

This paper is therefore an example that bridges

between a new technological methodology and the

problems protected areas face, opening a discussion

for these domains which can broadly interest

interdisciplinary studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial

support of “Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia”

(FCT), Portugal, through the MagIC research center

(Centro de Investigação em Gestão de Informação -

UIDB/04152/2020).

Assessing Informal Trails Impacts and Fragmentation Effects on Protected Areas using Volunteered Geographic Information

53

REFERENCES

Arnberger, A. and Brandenburg, C. (2002). Visitor struc-

ture of a heavily used conservation area: The Danube

Floodplains national park, lower Austria. In Arnberger,

A., Brandenburg, C. and Muhar, A. (Eds.) Proceedings

of the 1st international conference on monitoring and

management of visitor flows in recreational and pro-

tected areas (pp. 7-13).

Atzori, R. (2020). Destination stakeholders’ perceptions of

overtourism impacts, causes, and responses: The case

of Big Sur, California. Journal of Destination Market-

ing and Management, 17, 100440. 10.1016/j.jdm

m.2020.100440.

de Bie, K. and Rose, M. (2021). Community usage, aware-

ness and perceptionsVictoria, Australia. In Aas, Ø.,

Breiby, M., Selvaag, S., Eriksson, P. and Børrestad, B.

(Eds.) Proceedings of the 10st international conference

on monitoring and management of visitor flows in rec-

reational and protected areas (pp. 178-179).

Burke, J.A., Estrin, D., Hansen, M., Parker, A., Rama-

nathan, N., Reddy, S. and Srivastava, M.B. (2006). Par-

ticipatory sensing. Center for embedded network sens-

ing. Center for Embedded Network Sensing: UCLA.

Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item

/19h777qd.

Callau, A., Perez, Y. and Giné, D. (2020). Quality of GNSS

Traces from VGI: A Data Cleaning Method Based on

Activity Type and User Experience. ISPRS Interna-

tional Journal of Geo-Information. 9. 727.

10.3390/ijgi9120727.

Chua, A., Servillo, L., Marcheggiani, E. and Moere, A.

(2016). Mapping Cilento: Using geotagged social me-

dia data to characterize tourist flows in southern Italy.

Tourism Management, 57, 295-310.

Campelo, M. B. and Mendes, R.M.N. (2016). Comparing

webshare services to assess mountain bike use in pro-

tected areas. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tour-

ism, 15, 82-88.

Dickinson, J.E., Hibbert, J.F. and Filimonau, V. (2016).

Mobile technology and the tourist experience:

(Dis)connection at the campsite. Tourism Management,

57, 193-201.

Ghermandi, A., and Sinclair, M. (2019). Passive

crowdsourcing of social media data in environmental

research: A systematic review. Global Environmental

Change, 55, 36–47.

Goodchild, M.F. (2007). Citizens as sensors: The world of

volunteered geography. GeoJournal, 69(4), 211-221.

Heikinheimo, V., Minin, E.D., Tenkanen, H., Hausmann,

A., Erkkonen, J. and Toivonen, T. (2017). User-

generated geographic information for visitor

monitoring in a national park: A comparison of social

media data and visitor survey. ISPRS International

Journal of Geo-Information, 6(3), 85.

Jackson, S., Stevenson, K., Larson, L., Peterson. M. and

Seekamp, E. (2021). Outdoor activity participation

improves adolescents’ mental health and well-being

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res

Public Health, 18(5):2506.

Korpilo, S., Virtanen, T. and Lehvävirta, S. (2017).

Smartphone GPS tracking-inexpensive and efficient

data collection on recreational movement. Landscape

and Urban Planning, 157, 608-617.

Leung, Y.F. and Marion, J.L. (2000). Recreation Impacts

and Management in Wilderness: A state-of-knowledge

review. In: Cole, D.N., McCool, S.F., Freimund, W. A.,

Borrie, W. T. and O'Loughlin, J. Wilderness science in

a time of change conference. Missoula, MT. 23-27 May

1999, Proceedings RMRS-P-15-VOL-5. Vol. 5:

Wilderness ecosystems, threats, and management.

USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research

Station, Ogden, UT, USA.

Leung, Y.-F. and Marion, J.L. (1999). Spatial strategies for

managing visitor impacts in National Parks. Journal of

Park and Recreation Administration. 17(4): 20-38.

Leung, Y.F. and Louie, J. (2008). Visitor Experience and

Resource Protection Data Analysis Protocol: Social

Trails. North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, p.

17.

Levin, N., Lechner, A. M. and Brown, G. (2017). An

evaluation of crowdsourced information for assessing

the visitation and perceived importance of protected

areas. Applied Geography, 79, 115-126.

Marion, J.L. and Leung, Y.F. (2001). Trail resource impacts

and an examination of alternative assessment

techniques. Journal of Park and Recreation

Administration (Special Issue on Parks and

Greenways) 19.

Marion, J.L. and Leung, Y.-F. (2004). Environmentally

sustainable trail management. In: Buckley, R. (Ed.),

Environmental Impact of Tourism. CABI Publishing,

Cambridge, MA.

Mendes, R.N., Silva, A., Grilo, C., Rosalino, L., and Silva,

C. (2012). MTB monitoring in Arrábida Natural Park,

Portugal. In Fredman, P., et al. (Eds.) Proceedings of

the 6th international conference on monitoring and

management of visitors in recreational and protected

areas (pp. 32-33).

Muhar, A., Arnberger, A. and Brandenburg, C. (2002).

Methods for visitor monitoring in recreational and

protected areas: An overview. In Arnberger, A.,

Brandenburg, C. and Muhar, A. (Eds.) Proceedings of

the 1st international conference on monitoring and

management of visitor flows in recreational and

protected areas (pp. 1-6).

Norman, P., and Pickering, C.M. (2017). Using volunteered

geographic information to assess park visitation:

Comparing three on-line platforms. Applied

Geography, 89, 163-172.

Orsi, F., and Geneletti, D. (2013). Using geotagged

photographs and GIS analysis to estimate visitor flows

in natural areas. Journal for Nature Conservation, 21,

359-368.

Sessions, C., Wood, S.A., Rabotyagov, S., and Fisher, D.M.

(2016). Measuring recreational visitation at U.S.

National Parks with crowd-sourced photographs.

Journal of Environmental Management, 183, 703-711.

Volenec, Z., Abraham, J., Becker, A. and Dobson, A.

(2021). Public parks and the pandemic: How park usage

GISTAM 2022 - 8th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

54

has been affected by COVID-19 policies. PLoS ONE,

16(5): e0251799.

Walden-Schreiner, C., Leung, Y.-F., Newburger, T. and

Woiderski, B. (2012). Developing an accessible meth-

odology for monitoring visitor use patterns in open

landscapes of Yosemite National Park. Park Science,

29(1), 53-61.

Walden-Schreiner, C., Rossi, S.D., Barros, A., Pickering,

C. and Leung, Y. F. (2018b). Using crowd-sourced pho-

tos to assess seasonal patterns of visitor use in mountain

protected areas. Ambio, 47, 781-793.

Wang, D., Xiang, Z. and Fesenmaier, D.R. (2014). Adapt-

ing to the mobile world: A model of smartphone use.

Annals of Tourism Research, 48,11-26.

Wikiloc (2020). Wikiloc outdoor navigation. viewed Octo-

ber 2021, Retrieved from: https://www.wikiloc.com/

Wimpey, J. and Marion, J.L. (2010). The influence of use,

environmental and managerial factors on the width of

recreational trails. Journal of Environmental Manage-

ment, 91, 2028-2037.

Wimpey, J., Marion, J.L. (2011). A spatial exploration of

informal trail networks within Great Falls Park, Journal

of Environmental Management. VA. 92, 1012–1022.

Wong, E., Law, R. and Li, G. (2017). Reviewing geotagging

research in tourism. Proceedings of the International

Conference Information and Communication Technolo-

gies in Tourism, 2017, 43–58.

Wood, S.A., Guerry, A.D., Silver, J.M. and Lacayo, M.

(2013). Using social media to quantify nature-based

tourism and recreation. Scientific Reports, 3. 2976.

10.1038/srep02976.

Assessing Informal Trails Impacts and Fragmentation Effects on Protected Areas using Volunteered Geographic Information

55