UX of Chatbots: An Exploratory Study on Acceptance of User

Experience Evaluation Methods

Marcus Barbosa

1 a

, Walter Nakamura

2 b

, Pedro Valle

3 c

, Guilherme C. Guerino

4 d

,

Alice F. Finger

1 e

, Gabriel M. Lunardi

1 f

and Williamson Silva

1 g

1

Universidade Federal do Pampa (UNIPAMPA), Avenida Tiarajú, 810, Ibirapuitã, Alegrete, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

2

Instituto Federal do Amazonas (IFAM), BR 230, KM 7, Zona Rural, Humaitá, Amazonas, Brazil

3

Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF), Rua José Lourenço Kelmer - Martelos, Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil

4

Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM), Avenida Colombo, 5790, Maringá, Paraná, Brazil

Keywords:

Chatbots, Conversational Agents, User Experience, Evaluation.

Abstract:

Companies increasingly invest in designing, developing, and evaluating conversational agents, mainly text-

based chatbots. Chatbots have become the main and the fastest communication channel for providing customer

service and helping users interact with systems and, consequently, obtain the requested information. Despite

this, the potential market for chatbots,there is still too little known about evaluating the quality of chatbots from

a User eXperience (UX) perspective, i.e., the emotions, feelings, and expectations of users towards this appli-

cation. Besides, relatively little research addresses the feasibility and applicability of UX methods (generic or

not) or how to adapt them (if necessary) to evaluate chatbots. The goal of this research is to investigate the

adequacy, feasibility of use, and acceptance by users of UX methods when employed to evaluate a chatbot. To

achieve this objective, we conducted an exploratory study comparing three UX methods: AttrakDiff, Think

Aloud, and Method for the Assessment of eXperience. We compared these methods by assessing the degree of

ease of use, usefulness, self-predicted future use from end-users. Also, we performed follow-up interviews to

understand users’ perceptions about each method. The results show that users preferred to use the Think Aloud

method due to the ease and freedom that the user has to express their positive and negative emotions/feelings

while using the chatbot. Based on the results, we believe that combining the three methods was essential to

capture the whole user experience when using the chatbot.

1 INTRODUCTION

Conversational Agents (CAs) have become more

present in software applications because they allow

users to interact with machines through a natural lan-

guage (Rapp et al., 2021). The industry is increas-

ingly using CAs, especially those text-based natural

language (or chatbots), because chatbots serve as a

first line of support for customers seeking help and

product information in stores (Følstad and Skjuve,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5625-2934

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5451-3109

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6929-7557

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4979-5831

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4168-2872

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6655-184X

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1849-2675

2019). In recent years, chatbots have been the human-

machine interfaces that have received the most atten-

tion and investment from the software industry (Luger

and Sellen, 2016). Evaluating, collecting, and under-

standing user perception is a critical factor for the suc-

cess of a software application (Følstad and Skjuve,

2019). In the chatbot’s context, quality assessment

helps developers understand if the chatbot is easy to

use, usefulness, pleasant, meets expectations, and has

an easy-to-understand language, and other. There-

fore, it is essential to evaluate the chatbot’s quality.

In literature, a commonly way to assess the soft-

ware quality is through User Experience (UX) assess-

ment (Guerino et al., 2021). UX assessments help

software engineers to identify system problems, as

well as reveal user patterns, behaviors, and attitudes

during interaction with a particular product or ser-

vice (da Silva Franco et al., 2019). Based on these

Barbosa, M., Nakamura, W., Valle, P., Guerino, G., Finger, A., Lunardi, G. and Silva, W.

UX of Chatbots: An Exploratory Study on Acceptance of User Experience Evaluation Methods.

DOI: 10.5220/0011090100003179

In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2022) - Volume 2, pages 355-363

ISBN: 978-989-758-569-2; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

355

results, developers can understand and improve the

main points that resulted in a negative UX for users, in

addition to exploring the topics that positively influ-

enced users (Guerino et al., 2021). In recent years, re-

searchers have proposed several methods to evaluate

UX at different stages of the development (Rivero and

Conte, 2017). However, there is an emerging body

of empirical evidence research on the feasibility and

applicability of UX methods in chatbot contexts (Føl-

stad and Skjuve, 2019).

This work presents an exploratory study to ver-

ify the adequacy, feasibility of use, and acceptance

by users of UX methods when employed to evalu-

ate a chatbot called ANA. ANA is a chatbot created

to assist users with information related to COVID-

19, and its interaction is the textual-based conversa-

tion. We chose the main UX methods that can be

used by different users and allow evaluation in non-

conventional systems (as chatbots): AttrakDiff (Has-

senzahl et al., 2003), Think Aloud (Sivaji and Tzuaan,

2012) and Method for the Assessment of eXperience

(MAX) (Cavalcante et al., 2015). All three UX meth-

ods are commonly known and adopted in the literature

during UX evaluations (Lewis and Sauro, 2021). Be-

sides, these UX methods could be easily adapted in

the remote context (due to the COVID-19 pandemic),

both for data collection and analysis.

We are interested in investigating how researchers

can employ UX methods in context assessments chat-

bots. Then, we compared the methods in terms

of ease of use, usefulness, and self-predicted future

use. To do this, users answered a questionnaire,

adapted from the Technology Acceptance Model

(TAM) (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000), and they ex-

pressed their perceptions about each of the methods.

In addition, we conducted follow-up interviews with

users to better understand the strengths and weak-

nesses and understand whether the methods can be

complementary during the evaluation.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2

presents background about the UX and the UX eval-

uation methods; Section 3 presents the related works;

Section 4 describes the exploratory study; Section 5

presents the results obtained in this study; Finally,

Section 6 presents the discussions and future work.

2 BACKGROUND

User eXperience (UX) emerged as a research area that

studies the experiences generated from the relation-

ship between users and the final product. UX is de-

fined as “a person’s perceptions result from the use

and/or responses that UX use of a product, system, or

service” (ISO9241-210, 2011). In this sense, evaluat-

ing the UX of an application helps to assess positive

experiences that influence end-user satisfaction and

loyalty, and negative experiences can lead to prod-

uct abandonment (da Silva Franco et al., 2019). Re-

searchers are investigating how to evaluate and mea-

sure UX, and for that, several types of UX evalua-

tion methods have been proposed (Rivero and Conte,

2017). The UX evaluation methods commonly used

and adopted by software engineers are: AttrakDiff,

Think Aloud and MAX. Below we explain each one.

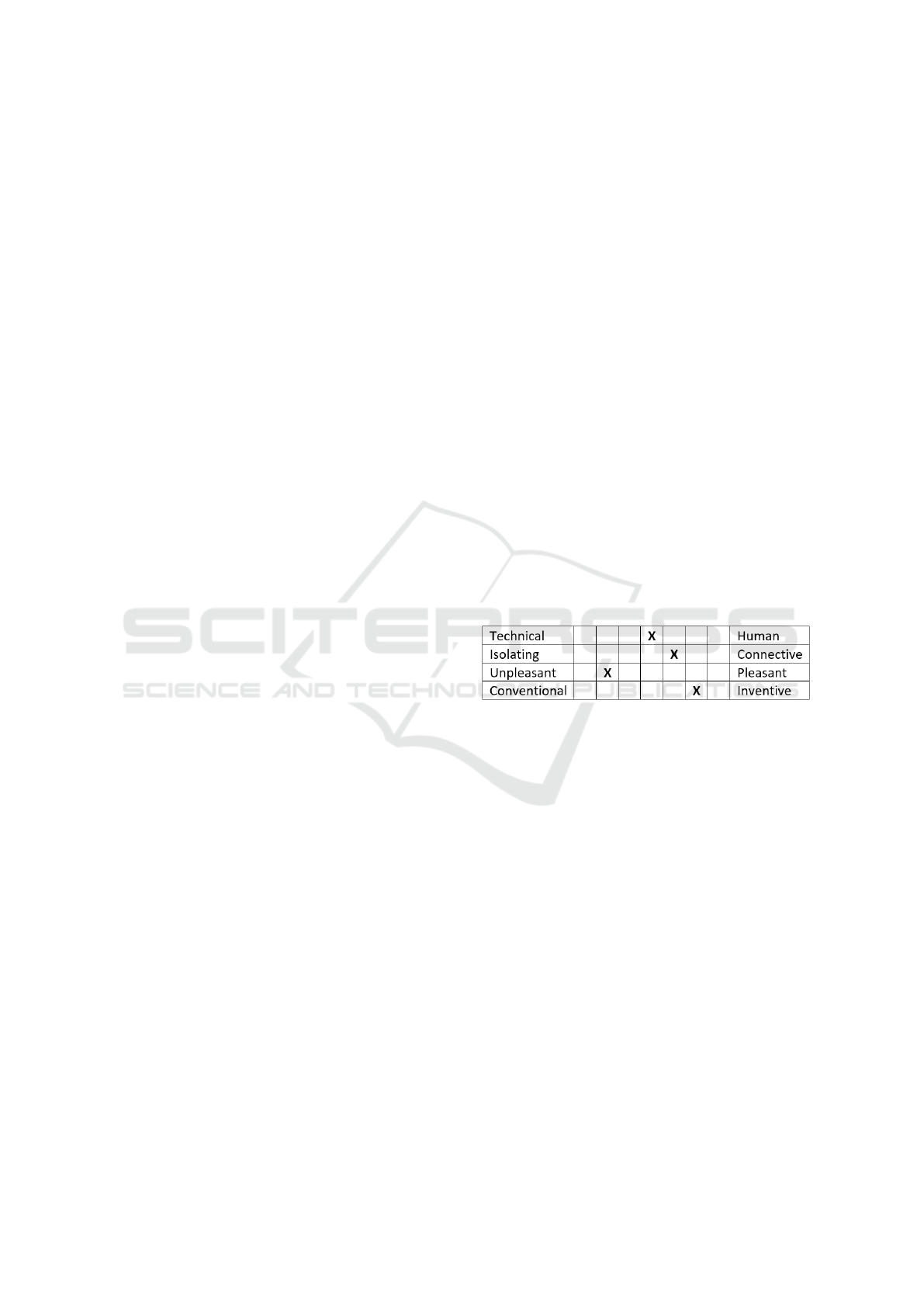

AttrakDiff is a UX method based on question-

naires that assess attractiveness through different as-

pects of an application (Hassenzahl et al., 2003). The

questionnaire compares the users’ expectations (be-

fore) and experience (after using the application).

AttrakDiff has opposing adjective pairs so potential

users can report their perceptions of the product.

Each pair represents an item that must be answered

based on a scale with a seven-point semantic differ-

ential, ranging from -3 to 3, with 0 being the neu-

tral point (Hassenzahl et al., 2003). The AttrakDiff

grouped the adjective pairs into four dimensions:

Pragmatic Quality, Hedonic Quality-Stimulation, He-

donic Quality-Identity and Attractiveness. Figure 1

presents the set of words from the AttrakDiff.

Figure 1: Part of AttrakDiff Questionnaire.

Another way to evaluate the UX of an application

is using UX Testing (also known as user experience

test) (Sivaji and Tzuaan, 2012). UX Testing is a kind

of evaluation based on real users’ feedback on the

application. One type of method, commonly known

and adopted in the literature for performing UX Test-

ing, is Think-Aloud Protocol (Alhadreti and Mayhew,

2018). By using Think Aloud, users perform pre-

defined tasks and are encouraged to comment on what

they are doing and why. At the same time, modera-

tors record users’ difficulties of use, comments, and

errors in a report. In addition, when the user ver-

balizes what feeling when using an application, ob-

servers can interpret a problematic part of the applica-

tion and note their remarks about the evaluation (Bar-

avalle and Lanfranchi, 2003).

Finally, MAX (Method for the Assessment of eX-

perience) is a method that aims to assess the over-

all experience after user interaction with the appli-

cation. MAX v2.0 allows users to report their ex-

perience through five categories arranged in a table.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

356

They are Emotion, Ease of Use, Usefulness, Attrac-

tiveness, and Intent. Each category has a symbol, a

color, and a set of cards. Related to the cards, each

one has a phrase and an avatar combined to repre-

sent the emotions/feelings. During the evaluation,

users choose the cards that best express their emo-

tions/feelings about that application in each category.

Figure 2 shows an example of MAX Board with some

cards in the categories.

Figure 2: MAX Board (v2.0) with some cards.

Due to the lack of sufficient experimental evi-

dence on the feasibility and acceptability of these UX

methods in the context of chatbots, we selected them

to conduct the exploratory study (Følstad et al., 2018).

3 RELATED WORK

In the literature, some works report evaluations con-

ducted on based-texts conversational agents from the

perspective of HCI. Below, we will present some of

the main works found.

Fiore et al. (2019) conducted user studies to assess

the acceptance and experience of 12 employees after

using a problem-solving chatbot. The results showed

that the chatbot actively guided the user through the

process and received very positive feedback. How-

ever, users had some negative comments when inter-

acting textually with the chatbot. Similarly, Jain et al.

(2018) evaluated the UX of 16 users while they were

interacting with eight chatbots for the first time. As a

result of the UX assessment, users commented that

they were frustrated and disappointed with the few

features provided by chatbots. The authors also re-

ported that users preferred chatbots that provided a

“human-like” natural language conversational ability.

Smestad and Volden (2018) performed a user

study that compared two versions of chatbots (one

customized according to the user and one not). The

authors used AttrakDiff to evaluate the experience of

using the two chatbot versions. As a result, the au-

thors noticed that the customized version of the chat-

bot performed better in hedonic and pragmatic quali-

ties than another version. Følstad and Skjuve (2019)

interviewed with 24 users of customer service chat-

bots to understand their experiences with chatbots. As

a result, the authors identified that users expect to use

chatbots more efficiently and always available. In ad-

dition, users expect answers to be easy to understand

and online self-service features always available.

From the studies mentioned above and other rel-

evant works in the literature (Guerino et al., 2021;

Rivero and Conte, 2017), the focus on evaluating the

users’ perceptions of generic chatbot aspects. Be-

sides, we observed that there is a lack of studies re-

porting the feasibility and applicability of UX meth-

ods (generic or not) or how to adapt them (if nec-

essary) to assess the UX in chatbots (Smestad and

Volden, 2018). This is essential due to the growing

number of chatbots developed each year to meet the

needs of the industry. Moreover, the existence of dif-

ferent UX evaluation methods makes it difficult to

identify those that are most suitable for the context

of chatbots or which of them can bring better results.

4 EXPLORATORY STUDY

We describe the activities of the study in the following

subsections.

4.1 Context

In this exploratory study, we selected the TeleCOVID

chatbot as an object of study to be evaluated by

UX techniques. A team of physicians and infor-

mation technology professionals developed the Tele-

COVID. The chatbot is based on two goals: screen-

ing COVID-19 suspects and educating the population

about COVID-19 (Chagas et al., 2021). TeleCOVID

has a conversational agent called ANA. The ANA

conversation agent interacts directly with the general

public, providing information related to COVID-19

such as types of symptoms, what kinds of treatments,

diagnoses, types of care that the population should

have, how to use the masks correctly, among others

(Fernandes et al., 2021). We chose this type of ap-

plication because it has become widely used during

the pandemic. This was possible due potential to pro-

vide information to all kinds of users at any time of

the day. The chatbot is available to the public at the

following link: https://telessaude.hc.ufmg.br.

Figure 3(a) presents the initial screen of user interac-

tion with the chatbot. Figure 3(b) shows an example

UX of Chatbots: An Exploratory Study on Acceptance of User Experience Evaluation Methods

357

where a user is looking for information to understand

what the coronaviruses are.

4.2 Subjects

We recruted seven users by convenience, all computer

science students. Their ranged from 22 to 26 years.

Four of them were undergraduate students, and three

were master’s students. They all knew how to pro-

gram and had participated in at least one UX eval-

uation and software development project (Academy

or Industry). All subjects use tablets/smartphones ev-

ery day. Regarding using voice-guided conversational

agents: (i) two users know about it but have never

used it; (ii) four users have already used it, but not

very often; and (iii) only one commented that he uses

it more often. Regarding the use of chatbots, six users

had already used this type of application, but not very

often. Table 1 depicts an overview of users’ profiles.

The label “U” and a number identify each user, e.g.,

U1 identifies user 1.

Figure 3: Screenshots of user interaction with ANA chatbot.

4.3 Indicators

We evaluated the acceptability of UX evaluation

methods from the users’ point of view. After evalu-

ating the ANA chatbot using the methods, users an-

swered an online post-study questionnaire adapted on

the indicators of the Technology Acceptance Model

(TAM) (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). The TAM indi-

cators are: Perceived Usefulnes, the degree to which

the subject believes that technology can improve their

performance at work; Perceived Ease of Use, the

degree to which the subject believes that using the

specific technology would be effortless; and Self-

predicted Future Use, the degree to which a subject

believes they will use the technology in future.

In this questionnaire, users answer according to

their degree of acceptance regarding the usefulness,

ease of use, and the self-predicted future use of each

method employed. Users provided their responses

on a seven-point scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Par-

tially Agree, Neutral, Partially Disagree, Disagree,

and Strongly Disagree). Table 2 describes the ques-

tions, based on the TAM indicators. We changed the

name of each method to only [method] to illustrate

where the identification of each method in the ques-

tionnaires would go. We focus on these indicators be-

cause they strongly correlated with user acceptance of

the technology (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000).

4.4 Instrumentation

Due to the social distancing caused by the pandemic,

we had to adapt the artifacts we would use during

the exploratory study. We used online tools available

through Google Workspace to support the elaboration

of the study instruments: (i) consent form guarantees

the confidentiality of the data provided and the user’s

anonymity; (ii) characterization questionnaire to char-

acterize users in UX design/evaluation, software de-

velopment projects, use of mobile applications, and

voice-based (e.g. Alexa, Siri) and text-based conver-

sational systems; (iii) documents contain the study

script, instructions on performing the chatbot evalu-

ation, and adaptation of the Methods (AttrakDiff and

MAX Board); (iv) presentation with generic instruc-

tions about the chatbot; (v) post-study questionnaires

contain questions based on TAM indicators; and (vi)

online rooms for conducting experiments.

4.5 Execution

Before the execution, we carried out a tutorial for the

users with basic instructions for accessing the chat-

bot platform. After that, we started the study. The

study had its execution fully adapted to the online

context. So, at first, we created the rooms for online

meetings via Google Meet and sent the links to each

selected user. We conducted each evaluation individ-

ually. As mentioned before, we performed the study

with only seven users. However, our study has been

of exploratory nature, we consider it acceptable.

After preparing the online rooms and waiting for

users to enter the rooms, we recorded the study. Then

we sent the link to an online document with the prepa-

ration roadmap via chat. This document shows the

links to online consent and characterization forms for

users to respond. We emphasize that the participa-

tion was voluntary, and all participants responded to

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

358

Table 1: User demographics.

Agers

(years)

Gender Academic

Degree

Familiarity with

UX

Familiarity with

Development

Familiarity

with Apps

Familiarity

with Voice

Familiarity

with Chatbot

U1 22 Male Student MSc Academic Projects Academic Projects Every day Rarely Rarely

U2 23 Male Student MSc Academic Projects Academic Projects Every day Always Rarely

U3 22 Male Student MSc Industry Projects Industry Projects Every day Rarely Always

U4 25 Female Undergrad Academic Projects Academic Projects Every day Never Rarely

U5 21 Male Undergrad Academic Projects Academic Projects Every day Never Rarely

U6 26 Female Undergrad Industry Projects Industry Projects Every day Rarely Rarely

U7 22 Male Undergrad Industry Projects Industry Projects Every day Rarely Rarely

Table 2: Questions based on TAM indicators.

Perceived Usefulness

PU1 Using the [method] improves my perfor-

mance by reporting my experience with the

chatbot.

PU2 Using the [method] improves my produc-

tivity by reporting my experience with the

chatbot.

PU3 Using the [method] enhances my effective-

ness in reporting aspects of my experience..

PU4 I find the [method] useful for reporting my

experience with the chatbot.

Perceived Ease of Use

PE1 The [method] was clear and easy to under-

stand.

PE2 Using the [method] did not take much men-

tal effort.

PE3 I think the [method] is easy to use.

PE4 I find it easy to report my experience with

the chatbot using the [method].

Perceived Self-Predicted Future Use

SP1 Given that I have access to the [method], I

predict that I would use it to evaluate my ex-

perience with an chatbot.

SP2 I plan to use the [method] to evaluate my ex-

perience with an chatbot.

the consent form. After that, the users received the

study instructions script via chat and watched the on-

line presentation about the chatbot. Each user per-

formed the following steps in the study:

• STEP 1 - Evaluating the User Expectations

– Watch a short presentation about the ANA chat-

bot.

– Report your user expectations via the

AttrakDiff method (online questionnaire).

• STEP 2 - Using the ANA Chatbot

– Share your device screen with the researchers.

– Access the chatbot via link: https://

telessaude.hc.ufmg.br.

– Please express your opinions aloud while you

perform the tasks described below. In this way,

we can track and understand what you are do-

ing and feeling.

– Please note the initial time.

– Do the following tasks in the Ana chatbot.

*

Task 01: Report that you are having difficulty

breathing;

*

Task 02: Report that you have had a fever for

at least two days;

*

Task 03: Search for information on how to

remove and put on the mask;

*

Task 04: Search for information about what

COVID-19 is;

*

Task 05: Search for information about

COVID-19 infections in dogs and cats.

– Note the final time of the chatbot.

• STEP 3 - Evaluating the Experience After Use

– Report your experience after using ANA chat-

bot via the AttrakDiff method.

– Report your experience using the MAX Board.

To do so, choose the cards (two at least) and

self-report your experience, explaining aloud

the choice of each card.

• STEP 4 - Evaluating the UX Methods

– Please, answer the TAM questionnaire describ-

ing your perception of each method employed

in this study.

– Briefly comment on your perceptions about

each method.

5 RESULTS

We adopted the median and the mean in this work for

comparison purposes. We used the mean to compare

the methods based on the TAM indicators. First, we

calculated the mean provided by users per item. Then,

we calculated the mean of each indicator. The results

with score for each indicator per method can be seen

in Table 3. We also used the median as the measure

to compare ordinal scales with the same number of

items (Wohlin et al., 2012), i.e, each item of the TAM

UX of Chatbots: An Exploratory Study on Acceptance of User Experience Evaluation Methods

359

indicators. Table 4 resents the results of the median

values (per method) related to each item of the TAM..

Table 3: Mean for each TAM indicator per UX method.

Indicators AttrakDiff Think Aloud MAX

PU 4.67 5.78 4.75

PE 4.89 5.64 5.67

SP 3.28 5.00 4.00

Table 4: Median for each item per UX method.

Items AttrakDiff Think

Aloud

MAX

PU1 5 6 5

PU2 5 6 5

PU3 5 6 4

PU4 5 6 5

PE1 5 6 6

PE2 6 6 6

PE3 5 6 6

PE4 5 6 6

SP1 5 6 5

SP2 3 4 3

Regarding Perceived Usefulness, the Think Aloud

obtained the highest mean and when we looked at the

indicator items, these also obtained the best results.

Thus, we conclude that this method was the one that

users found the most useful to be used. Regarding

AttrakDiff and MAX, these methods had very close

mean values of Usefulness. When we also observed

the medians of each item, we noticed a variation only

in item PU3 (AttrakDiff: 5; MAX: 4).

Think Aloud and MAX had the highest medians in

all items regarding the Perceived Ease of Use. When

we looked at the mean, MAX obtained 5.67 and Think

Aloud 5.64. We concluded that both methods are easy

to use. AttrakDiff, in this indicator, obtained an mean

value of 4.89. In items PE1 (ease of understanding

of the method), PE3 (ease of use of the method) and

P4 (it easy to report my experience), the AttrakDiff

obtained a median of five (5). We could relate it to the

fact that AttrakDiff is a questionnaire and that some

adjectives were confusing for users to understand.

Related to Perceived Self-predicted Future Use,

we noticed that this indicator had relatively low

mean values compared with the other two TAM in-

dicators. The think Aloud method got the best

mean result (5.00), followed by MAX (4.00) and

AttrakDiff (3.28). Observing the median of item SP2,

AttrakDiff, and MAX methods had medians equal to

3. Users remained neutral when answering whether

they intend to use the methods to evaluate their ex-

perience with an application in the future. For Think

Aloud, the median value was higher (4.00). We con-

cluded that users had a positive perception of Think

Aloud regarding the prediction and intention of using

it to evaluate chatbots in the future.

At the end, we also performed follow-up inter-

views with users to obtain more in-depth information

about the methods. The discussions help us under-

stand some issues that users faced when using the

methods, thus enriching some of the findings from

the quantitative results. We present the users’ positive

and negative perceptions about each one following.

Users commented that the Think Aloud method

is the easiest to use (mentioned by four users) because

it allows collecting a genuine user action: “I think

it captures the most genuine reaction possible from

the user” - U1. The method also gives freedom for

the user to express themselves openly (“(the method)

gives for user freedom to talk about how they are

feeling, their perception, and their actions” - U07),

and the evaluation makes something more personal

(“I think the method makes the evaluation a personal

thing” - U5). Users also commented that they would

probably use the method again in the future: “Think

Aloud was the easiest for me to use, and I would prob-

ably use it to evaluate some applications” - U2.

Related to MAX board method, users also found

it easy to use (mentioned by three users). It hap-

pened because MAX presents more visual aspects

than the other methods (“(MAX) is interesting be-

cause it brings emotions, I think it is more visual, and

I can explain myself better” - U3 ). Users need to

choose what card best represents their emotion mak-

ing easier how to express their experience and feel-

ings (“I found him easy to identify and express my

feelings. It considered my feelings” - U4).

Although users did not mention the AttrakDiff

method as easy to use, U7 comented that he enjoyed

evaluating using AttrakDiff because of how the word

pairs are structured: “I liked this method to evaluate

(...), I liked the axes that are dividing the words.”

U6 also commented that the feedback provided by

AttrakDiff could help the researcher to make com-

parisons of the results of expectation and experience:

“the before and after answer helps the researcher

compare the user’s expectation with what he felt even

after doing the evaluation.”

The quotes presented above present users’ positive

perceptions about the methods. However, we identi-

fied some difficulties faced by users while employ-

ing each method. The first negative point is related to

Think Aloud method. Users were afraid to say what

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

360

they were thinking in the beginning: “at first, I was a

little apprehensive because I said a lot of things good

or bad things, and it’s not always nice to talk” - U5.

We also realized this problem during the evaluation

and, whenever possible, we commented to the users

that they could express themselves openly. Users of-

ten forgot to express themselves aloud, U3 said that it

was challenging to comment every actions while us-

ing the chatbot: “I was trying to focus between doing

and speaking, this I found more complicated.”

Concerning the negative points of the MAX

method, U7 commented that the cards with emotions

are a little bit limited: “ due to limited cards, I missed

some negations and some affirmations.” U5 had some

difficulty choosing which cards best represented his

feeling due to the lack of emotions:“MAX doesn’t give

so many options. The blue (Usefulness), yellow (In-

tention), and purple (Attractiveness) could also have

more choices, so I took a moment to choose which

cards I would put on the board."

Related negative points of AttrakDiff, users felt

confused answering the questionnaire, because they

did not understand some adjective pairs (“some words

I got confused, you need to make a cognitive effort

for you to understand.” - U2). Users also commented

that some adjectives pair were vague or allowed users

had ambiguous interpretations: connective/isolating

(“do I feel isolated from chatbot?. . . do I feel con-

nected from the chatbot?” - U2); professional/ unpro-

fessional (“Professional regarding what? the infor-

mation? professional regarding the construction of

the chatbot?” - U2). Users also reported that some

pairs did not make sense for the application context:

“sometimes the words did not seem to make sense,

what do you mean appealing?” - U4. In these cases,

users commented that they answered in the central

item, as reported by U6 and U7, respectively: “sev-

eral questions I answered four because the item did

not make sense, and I’m trying to be neutral”; “I

marked half the scale because I wouldn’t be able to

respond.” Finally, the users pointed out the seven-

point scale adopted by AttrakDiff is quite large and

requires a certain cognitive effort from users, as men-

tioned in quotes below: “the questionnaires has a rel-

atively large scale for you put your opinions.” - U1;

“to me, there is a certain cognitive effort to answer

on that seven-point scale. I thought it was strange to

have a seven-point scale.” - U2

In general, we noticed that the users’ perceptions

corroborated the quantitative results identified in the

TAM. In addition, the results also reflect directly with

the results of the evaluations using the UX methods in

the ANA chatbot.

6 DISCUSSIONS AND FINAL

CONSIDERATIONS

Chatbots have become the main communication chan-

nel for providing customer service. However, there is

a lack of studies reporting the feasibility and applica-

bility of UX methods in chatbots contexts. In this pa-

per, we presented an exploratory study to understand

adequacy, the feasibility of use, and users’ acceptance

while using UX methods (AttrakDiff, Think Aloud

and MAX) to evaluate chatbots.

The results showed that users preferred to use the

Think Aloud method in the chatbot evaluation. This

preference is related to the ease and freedom that the

user has to express their positive and negative emo-

tions/feelings while using the chatbot. Although the

method allows this freedom, a negative point, from

the users’ point of view, is a shame, shyness, or even

fear of speaking, as users are afraid to comment on

something inappropriate. In this sense, researchers

need to make users as comfortable as possible to ex-

press themselves without fear. Furthermore, using

this method requires a lot of effort from the observer

since he/she needs to be aware of what the user will

comment on, observe his/her expression while using

the application, and then report. Also, depending on

the metrics used, the time to analyze the results can be

high. Our study only used the method to collect UX

issues that users reported. Thus, we spent more time

analyzing the recordings and the identified problems.

About AttrakDiff, the problems pointed out in this

work corroborate the results of other works. Mar-

ques et al. (2018), for example, reported that the

participants also had difficulties understanding some

AttrakDiff adjectives. Another problem, also men-

tioned by Marques et al. (2018), is that some of

the adjectives not fully fit into chatbots applications.

Researchers use the AttrakDiff in different contexts.

Consequently, this can negatively impact the results

of UX assessments in chatbots since users can an-

swer the questionnaire randomly and do not represent

their user experience, as mentioned by the users of

our study. From the researchers’ point of view, we

identified an issue concerning the data analysis. The

AttrakDiff authors provided a free website for other

researchers to adopt for analyzing the results in an au-

tomated way. However, when we tried to use it, it was

offline. As a result, we had a higher cost in analysis

time than expected since we had to create our own

spreadsheet to analyze the data.

Finally, we noticed that users felt comfortable dur-

ing the evaluation regarding MAX. Some users com-

mented that the method was easy to apply due to the

minimal cognitive effort required to use it. It pro-

UX of Chatbots: An Exploratory Study on Acceptance of User Experience Evaluation Methods

361

vides letters with phrases and emotions that reflect the

users’ experience. On the other hand, users also com-

mented it limits users to adapt their perception to the

available cards.

From our point of view, we believe that the meth-

ods complemented each other. AttrakDiff measures

UX through hedonic and pragmatic chatbot, compar-

ing users’ expectations and experience. However, be-

cause it is a scale-type questionnaire, users cannot ef-

fectively point out UX problems since this can only

be identified during interaction with the chatbot. The

Thinking Aloud method helped us to get explicit feed-

back from users with suggestions that can help de-

signers improve the chatbot. In AttrakDiff, the user

only chose among adjectives, and in Think Aloud,

the user was concerned with reporting their actions.

Complementarily, MAX helped users express them-

selves more openly about their user emotions, how

easy and helpful it was to use the chatbot, and their

intention to use it again. Therefore, we believe that

the three methods were essential to capture the whole

experience of users when using the chatbot. A limi-

tation of this research was that we evaluated from the

perspective of only one chatbot, and the usability of

UX methods depended only on this artifact.

Overall, we hope that the results of this study will

help promote and improve current practice and re-

search on UX in chatbots. In addition, we hope that

suggestions for improvements can contribute to the

evolving ANA chatbot. This work opens the possi-

bility for different relevant results: What are the main

factors that positively and negatively influence the ex-

perience of chatbot users? How can UX methods be

designed to capture the UX better? Is it better to adopt

quantitative, qualitative, or mixed metrics to evaluate

UX? How can we adopt machine learning to automate

UX assessments? In this sense, as future work, we

intend to carry out new UX evaluations with differ-

ent types of chatbots to verify a divergence between

the generated UX, adopting other UX methods, with

a larger sample, and in other domains (educational,

health, commerce).

REFERENCES

Alhadreti, O. and Mayhew, P. (2018). Rethinking thinking

aloud: A comparison of three think-aloud protocols.

In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Hu-

man Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–12.

Baravalle, A. and Lanfranchi, V. (2003). Remote web us-

ability testing. Behavior Research Methods, Instru-

ments, & Computers, 35(3):364–368.

Cavalcante, E., Rivero, L., and Conte, T. (2015). Max:

A method for evaluating the post-use user experience

through cards and a board. In 27th International Con-

ference on Software Engineering and Knowledge En-

gineering (SEKE 2015), pages 495–500.

Chagas, B. A., Ferreguetti, K., Ferreira, T. C., Prates, R. O.,

Ribeiro, L. B., Pagano, A. S., Reis, Z. S., and Meira Jr,

W. (2021). Chatbot as a telehealth intervention strat-

egy in the covid-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from

an action research approach. CLEI electronic journal,

24(3).

da Silva Franco, R. Y., Santos do Amor Divino Lima, R.,

Paixão, M., Resque dos Santos, C. G., Serique Meigu-

ins, B., et al. (2019). Uxmood—a sentiment analysis

and information visualization tool to support the eval-

uation of usability and user experience. Information,

10(12):366.

Fernandes, U. d. S., Prates, R. O., Chagas, B. A., and Bar-

bosa, G. A. (2021). Analyzing molic’s applicability

to model the interaction of conversational agents: A

case study on ana chatbot. In Proceedings of the XX

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 1–7.

Fiore, D., Baldauf, M., and Thiel, C. (2019). “forgot your

password again?" acceptance and user experience of

a chatbot for in-company it support. In Proceedings

of the 18th International Conference on Mobile and

Ubiquitous Multimedia, pages 1–11.

Følstad, A., Nordheim, C. B., and Bjørkli, C. A. (2018).

What makes users trust a chatbot for customer ser-

vice? an exploratory interview study. In Interna-

tional conference on internet science, pages 194–208.

Springer.

Følstad, A. and Skjuve, M. (2019). Chatbots for customer

service: user experience and motivation. In Proceed-

ings of the 1st international conference on conversa-

tional user interfaces, pages 1–9.

Guerino, G. C., Silva, W. A. F., Coleti, T. A., and Valentim,

N. M. C. (2021). Assessing a technology for usabil-

ity and user experience evaluation of conversational

systems: An exploratory study. In Proceedings of the

23rd International Conference on Enterprise Informa-

tion Systems (ICEIS 2021), volume 2, pages 461–471.

Hassenzahl, M., Burmester, M., and Koller, F.

(2003). Attrakdiff: Ein fragebogen zur messung

wahrgenommener hedonischer und pragmatischer

qualität. In Mensch & computer 2003, pages 187–196.

Springer.

ISO9241-210 (2011). Iso / iec 9241-210: Ergonomics of

human-system interaction – part 210: Human-centred

design for interactive systems.

Jain, M., Kumar, P., Kota, R., and Patel, S. N. (2018). Eval-

uating and informing the design of chatbots. In Pro-

ceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems

Conference, pages 895–906.

Lewis, J. R. and Sauro, J. (2021). Usability and user expe-

rience: Design and evaluation. Handbook of Human

Factors and Ergonomics, pages 972–1015.

Luger, E. and Sellen, A. (2016). " like having a really bad

pa" the gulf between user expectation and experience

of conversational agents. In Proceedings of the 2016

CHI conference on human factors in computing sys-

tems, pages 5286–5297.

ICEIS 2022 - 24th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

362

Marques, L. C., Nakamura, W. T., Valentim, N. M. C.,

Rivero, L., and Conte, T. (2018). Do scale type tech-

niques identify problems that affect user experience?

user experience evaluation of a mobile application (s).

In SEKE, pages 451–450.

Rapp, A., Curti, L., and Boldi, A. (2021). The human

side of human-chatbot interaction: A systematic lit-

erature review of ten years of research on text-based

chatbots. International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, page 102630.

Rivero, L. and Conte, T. (2017). A systematic mapping

study on research contributions on ux evaluation tech-

nologies. In Proceedings of the XVI Brazilian Sympo-

sium on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–10.

Sivaji, A. and Tzuaan, S. S. (2012). Website user experience

(ux) testing tool development using open source soft-

ware (oss). In 2012 Southeast Asian Network of Er-

gonomics Societies Conference (SEANES), pages 1–6.

IEEE.

Smestad, T. L. and Volden, F. (2018). Chatbot personali-

ties matters. In International Conference on Internet

Science, pages 170–181. Springer.

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical exten-

sion of the technology acceptance model: Four longi-

tudinal field studies. Management science, 46(2):186–

204.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., Höst, M., Ohlsson, M. C., Reg-

nell, B., and Wesslén, A. (2012). Experimentation in

software engineering. Springer Science & Business

Media.

UX of Chatbots: An Exploratory Study on Acceptance of User Experience Evaluation Methods

363