Examining the Effectiveness of Different Assessments and Forecasts

for Accurate Judgments of Learning in Engineering Classes

Christopher Cischke

a

and Shane T. Mueller

b

Department of Cognitive and Learning Sciences, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, U.S.A.

Keywords: Judgment of Learning, Zero-consequence Testing.

Abstract: Research and anecdotal evidence suggests that students are generally poor at predicting or forecasting how

they will do at high-stakes testing in final exams. We hypothesize that better judgments of learning may allow

students to choose more efficient study habits and practices that will improve their learning and their test

scores. In order to inform interventions that might provide better forecasts, we examined student data from

several university engineering courses. We examined how well three types of assessments predict final exam

performance: performance on ungraded exercises; student forecasts prior to exams, and performance on

graded material prior to exams. Results showed that ungraded exercises provided poor forecasts of exam

performance, student predictions provided marginal forecasts, as did prior graded work in the course. The

best predictor was found to be performance on previous high-stakes exams (i.e., midterms), whether or not

these exams covered the same material as the later exam. Results suggest that interventions based on prior

exam results may help students generate a better and more accurate forecast of their final exam scores.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the modern university classroom, instructors

frequently use high-stakes assessments such as

midterm or final exams to evaluate learning outcomes

and allow students to demonstrate competency. In

comparison to project-based or portfolio-based

assessments, exams have the benefit of ensuring a

comprehensive body of knowledge is mastered and

accessible at a specific point in time, but may harm

students with test anxiety or who have difficulty

managing stress involved with studying for numerous

final exams within a short period of time (Barker et

al., 2016). Perhaps even more challenging is that

many students have a poor understanding of whether

they have mastered the course material, and the types

of activities that are effective signals of their learning

(Carpenter et al., 2020). When it comes time to take

exams, students may rely on naive study habits such

as rereading notes and textbook chapters. Their

confidence in their knowledge of the material is

typically inflated (Hacker et al., 2000), and they

expect much higher scores on the exam than they

receive. So, in courses where high-stakes testing

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4316-4403

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7418-4592

makes up a large component of the grade, it is

troubling that students are known to be bad at

predicting what their grade might be, and so take

steps (either early, through better systematic study

habits, or late, via cramming) to improve their scores.

In order to develop new interventions that

improve student judgments of learning, we wanted to

evaluate how different potential measures and

assessments might serve to provide accurate

estimates of final high-stakes tests.

2 BACKGROUND

Research on forecasting has a number of systematic

biases, including lack of calibration and “collapsing”

estimates to chance estimates in domains where little

is known (Yates, 1982) and overconfidence in one’s

own performance (Clark & Friesen, 2009).

In the context of educational knowledge, students

exhibit similar biases. Researchers have suggested

that our judgments of learning may rely on retrieval

fluency (Benjamin et al., 1998), which is akin to the

use of the availability heuristic in general judgments

Cischke, C. and Mueller, S.

Examining the Effectiveness of Different Assessments and Forecasts for Accurate Judgments of Learning in Engineering Classes.

DOI: 10.5220/0011124500003182

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022) - Volume 1, pages 497-503

ISBN: 978-989-758-562-3; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

497

(Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). If a memory is

accessed quickly or with little effort, students may

believe that they have learned the material and that

they will be able to easily retrieve the same memory

in the future. This is a powerful and reasonable

heuristic in some cases. Benjamin, et al. (Benjamin et

al., 1998) found that the relationship between

predicted recall (based on retrieval fluency) and

actual recall was negatively related in many other

cases. They theorize that metacognition is simply a

special case of general cognition and therefore limited

by the same flaws and constraints. Individuals with

better memories are reported to have more accurate

predictions of future recall. However, even in

judgments of simple memory retrieval, researchers

have found that immediate judgments are poor

predictors of future recall, especially in comparison

to delayed judgments (Dunlosky & Nelson, 1992).

This may be because short-term memory activation

can produce strong retrieval fluency, providing an

inaccurate cue to later retrieval.

In educational contexts, research has suggested

that encoding fluency (how easy the experience of

learning something was) can also influence

judgments of learning. This can often be diagnostic

because information that is easier to learn is often

easier to recall later (Finn & Tauber, 2015). However,

this fluency can cause misjudgments as well, because

the low level of elaboration for “easy” topics may

lead to weaker encoding, whereas “hard” topics are

more richly (and therefore strongly) encoded.

Consequently, the “easy” topics are forgotten (though

the prediction would be for easy recall), and the

“hard” topics are remembered (though the prediction

would have been for little or no recall).

Both encoding and retrieval fluency impact how

students study and whether they believe they have

mastered the material. Students who study for exams

using passive methods (rereading textbooks, notes,

lecture slides, and other course materials, or

watching/listening to lecture recordings) are

generally accessing their knowledge in ways that

produce high recognition familiarity, which may

provide an inflated judgment of how well-learned the

material is (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006) and thus

inflated predictions of future recall.

Although students are well known to misjudge

their own understanding and learning, it is possible

that other early assessments in the classroom have the

potential to provide more accurate forecasts of later

performance. For example, the so-called “testing

effect” is widely known (see (Bjork et al., 2011; Pyc

& Rawson, 2010; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006)) as the

phenomenon that later performance on tests can

improve simply by repeated testing. The testing

intervention has been shown to be effective even

when no additional opportunities for studying are

given, indicating its benefit stems in part from things

like inference and retrieval practice. However, it may

also provide a more accurate early assessment of

learning that could then be used by the student to

adapt their study habits. Of course, a limitation of

early low-stakes testing is that if it does not matter,

students may not take it seriously, and thus it may not

provide a good indicator of future performance.

As a final possibility, we know that students

have different levels of ability, background

knowledge, time to devote to a course, and

personality variables such as test anxiety and

achievement motivation and we might expect that

these all contribute substantially to how well final

high-stakes exam scores can be forecasted. These are

factors that might be traits, or at least situationally

determined and unlikely to change within the course

of a semester-long class. To the extent that these

matter, other high-stakes assessments taken earlier in

the class (but on different material) might provide

good forecasts of final exam scores, even if they are

not direct judgments of learning on the tested

material.

Instructors then have three sources of data for

predicting student scores. One is using zero-

consequence testing as part of the coursework and

relating that to scores in the class. The second is

predictions made by the students themselves. Finally,

instructors can leverage existing scores as predictors

of future performance. In this analysis, we examine

all three.

3 CLASSROOM DATA

3.1 Practice Exercises as Predictors

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many college

classes went to fully remote delivery of instruction.

This caused instructors to restructure classes in

various ways, including utilizing technology in new

ways and leveraging learning management software

to provide additional “interaction” with students. In a

senior-level computer architecture course, a set of

practice exercises were provided to the students.

3.1.1 Method

These exercises were automatically graded for

correctness, but the scores were not included in the

final calculations for any student’s grade. The quizzes

A2E 2022 - Special Session on Analytics in Educational Environments

498

could be taken by the students any number of times,

though the maximum number of attempts by any

student was two. If the student provided an incorrect

response, they had the option to see the problem

worked out by the instructor, as the self-explanations

of worked examples are known to have positive

effects on future performance (Atkinson et al., 2000;

Metcalfe, 2017; Metcalfe & Huelser, 2020; Renkl &

Atkinson, 2002), even when the student made some

kind of error. Feedback was only the level of the

answer (VanLehn, 2011) and not at a step- or substep-

level.

3.1.2 Results

During the semester, no more than half of the students

attempted any of the ungraded exercises. Of those that

did, the testing effect was weak or non-existent. The

correlation between the overall scores on the practice

exercises and the scores on the exam was essentially

non-existent (r = .015). However, for the students

who did the practice problems and got them correct,

there was a weak correlation (r = .32) between doing

the practice problems and higher exam scores. When

students are presented with an opportunity to test their

knowledge in a zero-consequence environment, they

choose not to take it.

Across the sub-topics, correlations ranged from -

.18 to .18, and none were deemed significant

predictors at the p = .05 significance level. However,

a Bayes factor assessment of these correlations

produced values between .3 and .6, which indicates

ambivalence between the two hypotheses.

3.1.3 Discussion

This study showed that neither attempts nor

successful completion of ungraded practice exercises

provide a strong indicator of later exam performance.

Given the small sample size, it is probable that there

is some predictability between performance on these

exercises and later exam scores, but this is unlikely to

account for more than 10% of the variance in this

relationship. It is possible if these exercises were

required that they would have provided a better

predictor, but this may undermine the pedagogical

value of having low-stakes formative assessments of

knowledge.

3.2 Student Predictions

Perhaps students choose not to engage with these

exercises because they believe their current

knowledge level suffices to succeed in the class. To

examine whether students could accurately forecast

their exam scores, we prompted them with questions

at the beginning and end of the exam, similar to the

method employed by Hacker (Hacker et al., 2000)

and Hartwig (Hartwig & Dunlosky, 2017).

3.2.1 Method

Students in two computer engineering courses (18

students in a junior-level embedded systems class and

28 in a senior-level computer architecture class) were

asked to predict their exam scores in both the first and

last question of an online midterm exam. The first

question was, “If you are willing, tell me

approximately what percentage score you expect to

get on this exam. If you answer this question and the

corresponding question at the end of the exam, you

will receive one extra credit point.” At the end of the

exam, the corresponding question was, “Now that you

have completed the exam, what percentage do you

think you will get?” As indicated in the question,

students were granted one extra credit point for

answering both of these questions. All students in

both classes chose to answer the question. Some

students provided elaboration for their predictions in

the free-entry textbox.

3.2.2 Results

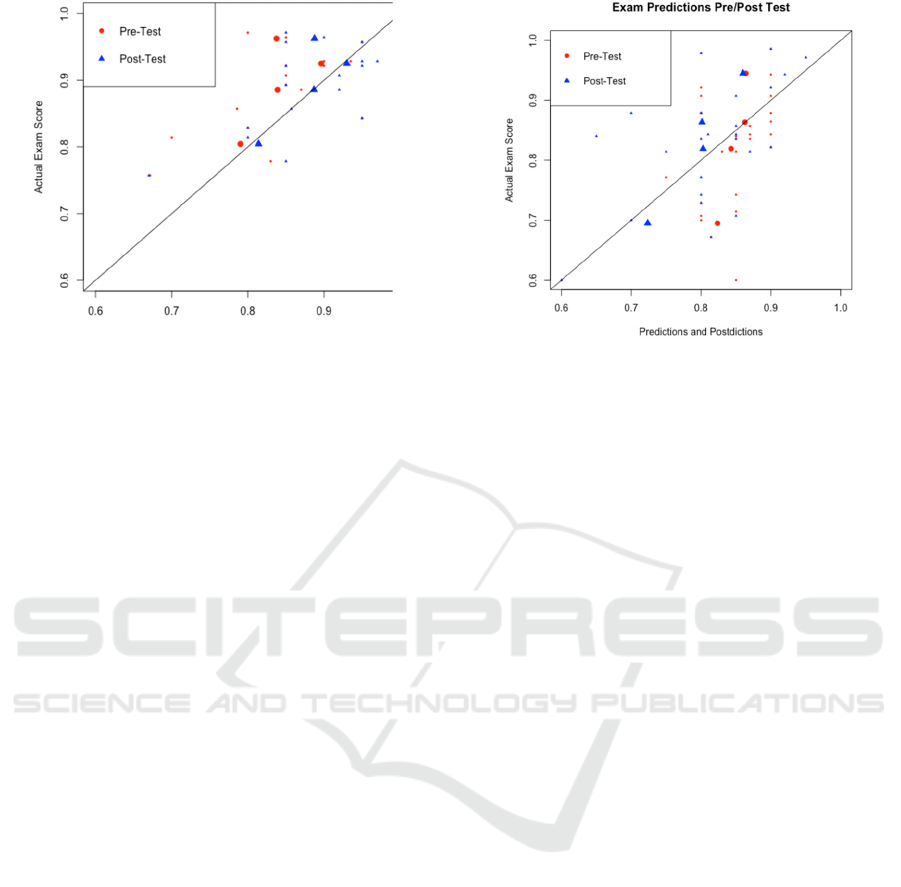

Figure 1 shows the results from the junior-level class.

The line indicates perfect prediction. Every data point

above and to the left of the line indicates

underconfidence. Every data point below and to the

right of the line indicates overconfidence. The scores

have been clustered into quartile means. In this case

(n = 18), the students were slightly underconfident –

a paired-samples t-test showed that pre-test

predictions under-predicted performance by about

5% (t(16)=2.7, p=.013), but post-test predictions

were not significantly biased (t(16)=.87, p=.4). In the

aggregate, they have come close to reality in this case.

However, the correlation measurements between

predicted and actual scores were r = .47 (p=0.55)

before the test and r = .61 (p=.009) for post-test

predictions.

Figure 1 shows the results for the senior-level

class. For this slightly larger class, a pattern similar to

that observed by Hacker (Hacker et al., 2000) is seen.

High-performing students underpredict their score by

a half-grade, and low-performing students

overpredict their score by a full grade or more. There

was no overall over- or under-estimate of grade,

either pre-test (t(27)=1.0, p=.308) or post-test

(t(27)=1.84, p=.08). All of the students bring their

estimations closer to reality in the post-test

predictions. The two middle quartiles become

Examining the Effectiveness of Different Assessments and Forecasts for Accurate Judgments of Learning in Engineering Classes

499

Figure 1: Mean scores for junior-level students for pre-test

and post-test predictions.

somewhat less certain of their performance. The

lowest quartile remains overconfident. Driven

especially by the optimism of the lowest quartile, the

pre-test predictions correlated to the actual scores

poorly (r = .37, t(26)=2.0, p=.054), but post-test

predictions rebounded slightly (r = .52, , t(26)=3.1,

p=.004). It should be noted that these post-test

predictions are the best-case student predictions.

They have completed the exam but are still limited in

their ability to predict the outcome.

As part of their assessments, about half gave

reasons for their estimates. The most common

justifications were non-specific feelings about how

well they knew the material, and specific pointers to

how they had done on homework.

3.2.3 Discussion

This study shows that student forecasts of exam

grades were systematically biased, and not

significantly predictive of exam scores, except for

after the exam had already been taken. However,

because the correlations were moderately large (r=.37

to .47), and approached significance at a p=.05 level

with a fairly small sample size, this potentially

represents a better predictor than performance on the

zero-consequence assessments examined in the first

study. However, these correlations represent just 13-

22% of the variance between forecasts and exam

scores, so a majority of the performance remains

outside of students’ judgments. Next, we will turn to

using other exam scores to predict final exam

performance.

Figure 2: Mean scores for senior-level students for pre-test

and post-test predictions. Large symbols indicate quantile

means.

3.3.1 Method

Homework and test scores from a total of 98 students

enrolled in a sophomore-level electrical engineering

class were analyzed. This involved seven graded

homework assignments, one quiz, two mid-term

exams, and a cumulative final exam. We completed

two linear regression analyses: one using Exam 2

score as an outcome and all previous work as

predictors, and one using the final exam score as the

outcome and all previous work as predictors (results

in Table 1).

3.3.2 Results

The first column of Table 1 shows the coefficients

and eta

2

values for each predictor of the second exam

performance. The only statistically significant

predictor of student performance on the second

midterm exam (Exam 2) is the performance on the

first midterm, which explains about 14% of the

variance. The second column shows the predictors of

the final exam score, and here that Exam 2 and

homework 7 were statistically significant at p < .05,

whereas homework 1 and Exam 1 were marginally

significant at p < .1.

3.3.3 Discussion

The results of this analysis showed that earlier exam

scores provide the strongest prediction of later exam

scores. This was true for the relationship between

exam 1 and exam 2 (which covered different

material) and for the relationships between the first

two exams and the final exam (which was cumulative

over the material covered in the earlier exams). Of

A2E 2022 - Special Session on Analytics in Educational Environments

500

course, there are knowledge dependencies across the

course, but the content of the first two exams covered

different material. These results suggest that other

high-stakes comprehensive tests are perhaps the best

predictor of final exam scores.

4 GENERAL DISCUSSION

The results of these studies suggest that student

forecasts of exam performance are only moderately

good, and that performance on low-stakes formative

assessments were also unpredictive, but scores on

other high-stakes exams were significantly predictive

of final exam scores. This might be partially

explained by the “testing effect” discussed earlier, in

that the act of taking earlier tests might improve

performance on later tests. However, this might also

be attributable to the earlier exams measuring specific

knowledge and academic or motivational traits that

are responsible for success on later exams.

The fact that students fail to utilize testing as both

a measure and means of learning should indicate that

results from cognitive science have not necessarily

found their way into common knowledge or

pedagogy.

It is difficult to prove conclusively that students

choose not to use the practice exercises solely due to

a preference for “traditional” study sessions when

there are other social factors that could be driving

those decisions. It has historically been difficult to

motivate students to do work that does not directly

affect their grades.

In our first study, students who did use the

practice exercises but got them wrong did not see any

increase in test performance. This might be explained

by the results of Rowland (Rowland, 2014), who

suggested that more effortful testing events yield a

larger testing effect. Since these practice exercises

were always quite basic questions and students were

free to refer to notes and other resources while they

completed the exercises, it is possible that the

retrieval effort was minimal and so it did not confer a

testing benefit. Alternatively, perhaps the students

who did the exercises correctly are the same

conscientious and high-performing students who

would have gotten the corresponding questions on the

exam correct without the extra practice of the

exercises. But low-stakes formative evaluation may

be valuable nevertheless. Perhaps the reason it does

not correlate with final exam performance is that

students who attempted it and failed changed their

study habits to improve their skills in those specific

areas.

Table 1: Linear regression coefficients for predicting exam

scores based on other assignments. Partial eta

2

values are

shown in parentheses, which indicate the proportion of

variance accounted for by each predictor.

Dependent variable:

Exam2 FinalExam

(1) (2)

HW0 -0.565 (0.00) 0.849 (0.04)

HW1 0.032 (0.20) 0.264

*

(0.44)

HW2 0.021 (0.07) 0.167 (0.21)

HW3 0.021 (0.01) 0.184 (0.12)

HW4 -0.018 (0.04) 0.009 (0.08)

HW5 0.072 (0.12) 0.061 (0.13)

HW6 0.050 (0.02) 0.092 (0.05)

HW7 0.0001 (0.00) 0.099

**

(0.06)

`Quiz 1` 0.039 (0.00) -0.079 (0.00)

Exam1 0.473

***

(0.14) 0.505

*

(0.11)

Exam2

0.604

***

(0.09)

Observations 98 98

R

2

0.406 0.646

Adjusted R

2

0.338 0.600

Residual Std.

Error

4.196 (df = 87) 7.995 (df = 86)

F Statistic 5.958

***

(df = 10; 87) 14.239

***

(df = 11; 86)

Note:

*

p<0.1,

**

p<0.05,

***

p<0.01

One caveat of the testing effect is that it is most

often seen with a delay between the first test (in this

case, the practice exercises) and the second.

Otherwise, restudy has equal or greater benefits.

Practically speaking, when students “cram” prior to

an exam, they can perform well on the assessment

even though the long-term retention is lower. If

exams are seen predominantly as gateways (“I need

to get a good grade on this test in order to pass the

class and get my degree”) instead of learning events

(“This exam helps reinforce my understanding of the

material”), instructors will struggle to get student

buy-in on additional testing events.

From a curriculum design point of view, our

research suggests that performance on zero-stakes

practice exercises did not provide a strong predictor

of test performance. When including them, however,

Examining the Effectiveness of Different Assessments and Forecasts for Accurate Judgments of Learning in Engineering Classes

501

the exercises should be of at least moderate difficulty

in order to maximize retrieval effort and spaced

appropriately throughout the duration of the class to

provide the maximal benefit.

The third study using linear regressions supports

an unsurprising truth: Exam performance predicts

exam performance. This is, in part, simply transfer-

appropriate processing (Rowland, 2014). However, it

highlights that homework assignments and exams are

fundamentally different forms of student assessment

and should be recognized as such by students and

faculty alike. Students that anchor their expectations

for exams based on homework performance may be

mistaken. While communicating this to students is

important in order to encourage profitable study

techniques, it is simultaneously critical that

instructors do not imply that students are unable to

prevent their previous exam scores from inevitably

predicting the future. A student who wishes to

perform better on a future exam must change the way

that they have approached past exams.

5 CONCLUSION

Students, even late in their university careers, still do

not make good judgments of what they know. Their

own evaluations are often based on recall fluency or

scores on dissimilar assessments, neither of which

provide strong predictive power for exam scores. The

question that remains is how to provide tools that

provide more insight into a student’s current state of

understanding so that they might more closely align

their predictions with reality. Ideally, they would

even address the deficiencies prior to the exam.

Constructive activities such as concept mapping, self-

test, or question generation may be valuable if the

student can be induced to complete the activity and

there is a method of assessing the activity.

Determining the effectiveness of such interventions

remains an open question and a topic for future

research.

REFERENCES

Atkinson, R. K., Derry, S. J., Renkl, A., & Wortham, D.

(2000). Learning from Examples: Instructional

Principles from the Worked Examples Research.

Review of Educational Research, 70(2), 181–214.

https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070002181

Barker, S. B., Barker, R. T., McCain, N. L., & Schubert, C.

M. (2016). A randomized cross-over exploratory study

of the effect of visiting therapy dogs on college student

stress before final exams. Anthrozoös, 29(1), 35–46.

Benjamin, A. S., Bjork, R. A., & Schwartz, B. L. (1998).

The mismeasure of memory: When retrieval fluency is

misleading as a metamnemonic index. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: General, 127(1), 55.

Bjork, E. L., Bjork, R. A., & others. (2011). Making things

hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable

difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the

Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental

Contributions to Society, 2(59–68).

Carpenter, S. K., Witherby, A. E., & Tauber, S. K. (2020).

On Students’ (Mis)judgments of Learning and

Teaching Effectiveness. Journal of Applied Research in

Memory and Cognition, 9(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.12.009

Clark, J., & Friesen, L. (2009). Overconfidence in forecasts

of own performance: An experimental study. The

Economic Journal, 119(534), 229–251.

Dunlosky, J., & Nelson, T. O. (1992). Importance of the

kind of cue for judgments of learning (JOL) and the

delayed-JOL effect. Memory & Cognition, 20(4), 374–

380.

Finn, B., & Tauber, S. K. (2015). When Confidence Is Not

a Signal of Knowing: How Students’ Experiences and

Beliefs About Processing Fluency Can Lead to

Miscalibrated Confidence. Educational Psychology

Review, 27(4), 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s10648-015-9313-7

Hacker, D. J., Bol, L., Horgan, D. D., & Rakow, E. A.

(2000). Test prediction and performance in a classroom

context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1),

160–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.160

Hartwig, M. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2017). Category learning

judgments in the classroom: Can students judge how

well they know course topics? Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 49, 80–90. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.12.002

Metcalfe, J. (2017). Learning from Errors. Annual Review

of Psychology, 68(1), 465–489. https://doi.org/10.1146/

annurev-psych-010416-044022

Metcalfe, J., & Huelser, B. J. (2020). Learning from errors

is attributable to episodic recollection rather than

semantic mediation. Neuropsychologia, 138, 107296.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.1072

96

Pyc, M. A., & Rawson, K. A. (2010). Why Testing

Improves Memory: Mediator Effectiveness

Hypothesis. Science, 330(6002), 335–335.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1191465

Renkl, A., & Atkinson, R. K. (2002). Learning From

Examples: Fostering Self-Explanations in Computer-

Based Learning Environments. Interactive Learning

Environments, 10(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/

10.1076/ilee.10.2.105.7441

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-Enhanced

Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term

Retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

A2E 2022 - Special Session on Analytics in Educational Environments

502

Rowland, C. A. (2014). The effect of testing versus restudy

on retention: A meta-analytic review of the testing

effect. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1432–1463.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037559

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A

heuristic for judging frequency and probability.

Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232.

VanLehn, K. (2011). The Relative Effectiveness of Human

Tutoring, Intelligent Tutoring Systems, and Other

Tutoring Systems. Educational Psychologist, 46(4),

197–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.

611369

Yates, J. F. (1982). External correspondence:

Decompositions of the mean probability score.

Organizational Behavior and Human Performance,

30(1), 132–156.

Examining the Effectiveness of Different Assessments and Forecasts for Accurate Judgments of Learning in Engineering Classes

503