Collaborative Business Model Structures for a Digital Care Platform:

Value Proposition, Partners, Customer Relations, and Revenues

Jelena Bleja, Sara Neumann, Tim Krüger and Uwe Grossmann

Faculty of Business/IDiAL, University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Dortmund, Germany

Keywords: Collaborative Business Models, Marketplace, Brokerage Platform, Digital Care Platform, Allocation.

Abstract: The shortage of skilled workers and complex challenges arising from the aging of society, emphasize the

relevance of collaboration between stakeholders. Furthermore, a collaboration between interdisciplinary

stakeholders gather expertise and practical knowledge to successfully establish a collaborative business model

on the market. Especially in the care sector, this need becomes clear. For this, a digital care platform is

developed to efficiently manage the shortage of skilled workers, connect people with assistant needs and

service providers in a cost-efficient manner and distribute efficiency gains throughout the collaboration

network. This makes a collaborative business model that presents the way collaboration is to be built necessary

and shows financing as well as efficiency gains and revenue allocation possibilities between the stakeholders.

Thus, collaborative business model structures are presented in this paper to show how a collaboration of

stakeholders can be successful. The analyses show the many possibilities to finance a care platform depending

on the chosen business model. Especially promising seems to be a combination of financing models. The

identified further challenge is to emphasize the added value a care platform brings to service providers and

users alike.

1 INTRODUCTION

Demographic change is a process that arises from

complex problematic issues and makes innovative

solution strategies necessary. These challenges

include political, economic, and social dimensions

(Schwarting, 2018). In this context, coping with the

shortage of skilled workers will become particularly

relevant because of the increasing aging of society

(Schwarting, 2018). For the increasing development

of smart services and platforms, solutions are relevant

that meet the complexity of upcoming projects and

issues. The joint project Smart Care Service

1

addresses this specific challenge by developing a

digital care platform that manages the shortage of

skilled workers efficiently, connects people with

assistant needs and service providers, and responds to

changing customer demands. An approach to this is a

collaboration with multiple stakeholders and the

development of a collaborative business model

(Bullinger et al., 2017). The development of

1

The EU and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (EFRE.NRW),

as part of the European funding program for regional development,

fund the Smart Care Service project.

collaborative business models is an aim of Smart Care

Service. The project aims to develop a digital care

platform with multiple stakeholders from different

breaches who bring in specific expertise in the

process. For this, all relevant aspects for the

development of a care platform will be considered.

An example in which the collaboration of

multiple business partners is necessary is the Ambient

Assisted Living (AAL) area. Collaboration from

multiple stakeholders within the AAL area lead to

high quality care services, increasement of outreach,

and cost savings. Furthermore, a high number of

collaborators is imperative for innovations to develop

(Memon et al., 2014; Mukhopadhyay & Bouwman,

2018). Various innovative technologies are used to

enable older people and people with assistant needs

to live autonomously at home for as long as possible,

such as motion tracking or smart devices in the

household (Bleja et al., 2020). Even though the

development of collaborative business models is

challenging for the stakeholders, as a high number of

Bleja, J., Neumann, S., Krüger, T. and Grossmann, U.

Collaborative Business Model Structures for a Digital Care Platform: Value Proposition, Partners, Customer Relations, and Revenues.

DOI: 10.5220/0011143300003280

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies (ICSBT 2022), pages 111-119

ISBN: 978-989-758-587-6; ISSN: 2184-772X

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

111

collaborators also lead to high complexity and

organizational effort, there are also several benefits

(Mukhopadhyay & Bouwman, 2018). Besides the

gain of know-how, collaborations also create new

revenue streams and distribution channels, new

networking partners, and cost savings in the

production of goods and services (Bartels et al., 2020).

Therefore, partners can contribute their expertise and

practical knowledge to gain business advantages.

In this paper, two possible business models for a

digital care platform are presented. The marketplace

platform and the brokerage platform are the results of

intensive literature review and business model

development. The two types are the basis for the

collaborative business model that is developed in this

paper.

Initially, the business model definition, as well as

a possible developing process, will be considered in

chapter 2. In this, the two possible business model

alignments for a digital care platform (marketplace

platform and brokerage platform) will be compared.

The differences will be explained in chapter 2.1. Then,

based on these models, the collaborative business

model structures will be shown relating to a care

platform (chapter 2.1.3). Furthermore, benefits and

challenges will be worked out and important aspects

such as the forms of collaboration and their structures

will be emphasized. While the advantages of

collaborative business models are the focus of this

paper, the challenges of this type of business model

will also be considered and solution

recommendations are given. A special focus lies on

the financing and revenue potentials of a care

platform (see chapter 3).

Finally, open questions for future research are

presented in the further work section and the

conclusion.

2 BUSINESS MODEL

STRUCTURES

Smart services will influence many areas of society in

the future. These areas include, among others,

education, the production of services and products,

infrastructure, and healthcare (Marquardt, 2017). The

changes within these areas make new business

models necessary. For this, existing business models

have to be adapted or entirely new business models

have to be created. Before this, a definition of what a

business model is, is necessary.

Marquardt (Marquardt, 2017) emphasizes that a

consistent definition of a business model is

challenging, as the several existing business model

structures are not distinguishable. A business model,

as Kimble (Kimble, 2015) elaborates, describes how

a company operates. For this, the business model will

be reduced to its key points and the relationships of

the stakeholders will be analyzed. Examples of

business model structures include the models by

Zott/Amitt (Zott & Amit, 2010), Björkdahl

(Björkdahl, 2009), and Chesbrough (Chesbrough,

2010). Even though it is complicated to find a holistic

definition of what a business model is, several

existing business model structures unite in the

inclusion of a value proposition, e.g. Teece (Teece,

2010), Osterwalder, and Pigneur (Osterwalder &

Pigneur, 2010). The aim of the implementation of a

business model is the sustainable positioning in the

market. To accomplish this, Bartels et al. show a

possible approach to business model development

based on several phases (Bartels et al., 2020).

Firstly, the business environment has to be

analyzed based on its strengths and weaknesses as

well as external strengths and weaknesses. A SWOT

analysis could be a suitable method for this step. A

Value Proposition Analysis is also a promising

method in achieving the aim of reviewing the

business environment. The Value Proposition

Analysis works out the concrete value proposition of

the possible business model (Bartels et al., 2020).

Secondly, ideas of different business models will be

brainstormed in a team using different creative

techniques and methods. The ideas will be

concretized and evaluated – facilitating the final

decision on which business model to choose and work

with. Furthermore, the assumptions on which a

business model is based are examined. Qualitative

methods, such as expert or group interviews, and

quantitative methods, such as surveys, targeting the

respective target groups are suitable for this purpose.

Next, a prototype phase in which the acceptance of

the target groups and the feasibility of the project will

be evaluated is crucial (Bartels et al., 2020). In this

phase, possible challenges can be identified and

tackled. In the final phase, the company will

implement its business model with a market launch

(Bartels et al., 2020).

For a more detailed analysis, the business model

canvas by Osterwalder and Pigneur will be used

(Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). According to the

authors, a business model consists of the following

key points: key partners, key activities, key resources,

customers relationships, channels, customer

segments, cost structure, revenue streams, and value

propositions (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). The

examination of the value proposition is especially

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

112

promising as different business models create

different value propositions and – as stated – the value

proposition is a uniting characteristic of different

business models. Osterwalder describes value

proposition as what added value a business model

offers to customers (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

Relating to a digital care platform it is questionable,

whether the platform is designed as a marketplace

platform or brokerage platform. Marketplace

platforms offer a dashboard on which customers can

network with service providers to book a care service.

An example of a marketplace platform is idealo. On a

brokerage platform like Amazon, the communication

and the establishment of contact are initialized by the

platform. The platform communicates with the

customer and the service provider. This reduces

administrative work for the service providers.

The type of platform does not only influence the

value proposition but it influences other key points of

a business model as well. Additionally, it makes

special data usage concepts necessary for the

responsible use of user data. This challenge will be

explained in more detail later on.

In the following, the two mentioned types of

business models will be in focus. There will be an

explanation of how the business models are built and

what their value propositions are. The types of

platforms are the marketplace platform and the

brokerage platform. The presented models are built in

the same way to show several users and several

providers of the potential platform. Furthermore, the

models contain the same main elements: The payment

flows, the service flows, and the information flows

are the main elements to demonstrate the

relationships between the stakeholders in detail. This

also enhances the clear structure of the business

models that are discussed. Afterward, collaborative

business model structures – derived from the previous

types of platforms – are presented (chapter 2.1.3).

2.1 Alignment of the Care Platform

In this chapter, the marketplace platform and the

brokerage platform will be described and compared

with each other in more detail. For this, the

relationships between the platform, the service

providers, and the users will be presented about

different action flows that happen on these platforms.

These flows include the payment flows, the service

flows and the information flows. The special

particularities with regard to a care platform will be

demonstrated in this chapter using an example – a

care consultation with regard to AAL services on a

care platform.

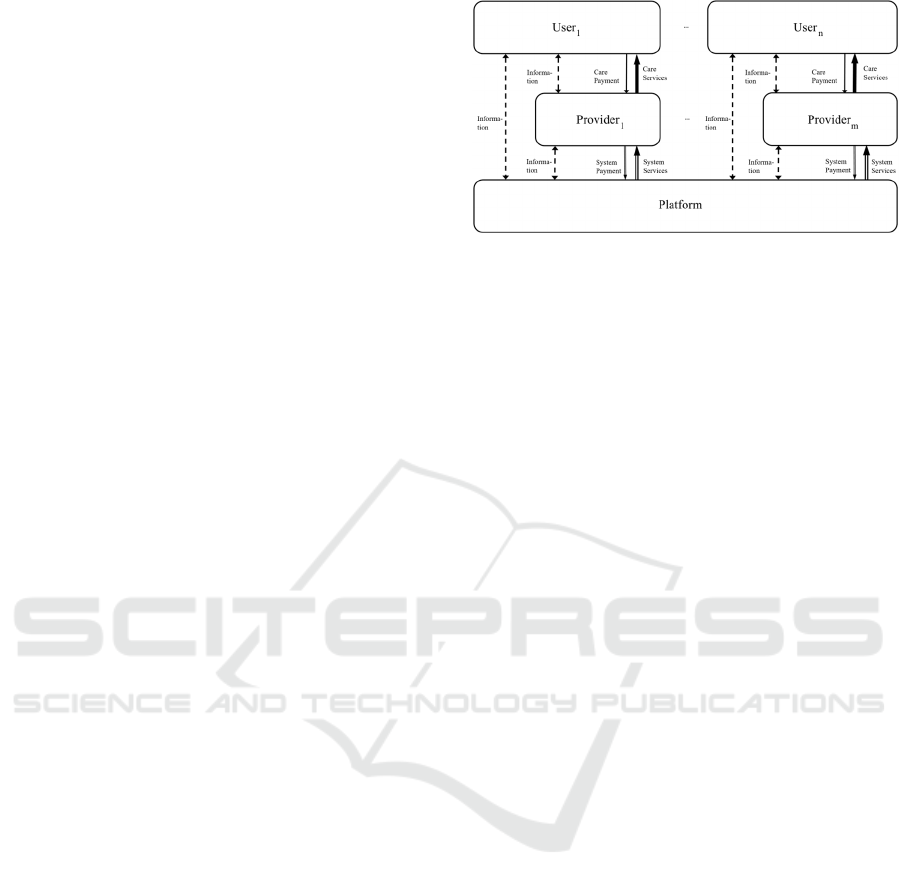

Figure 1: Marketplace Platform (Bleja, Krüger, Neumann,

et al., 2022).

2.2 The Marketplace Platform

Marketplace platforms can be identified by several

characteristics. Täuscher and Laudien summarize

marketplaces as platforms on which independent

stakeholders network with others. Moreover, the

stakeholders can enter into business relationships, and

thirdly, the marketplace platform offers a framework

for transactions. Another important criterion is that

the platform does not offer any services but is solely

the place where different stakeholders meet

(Täuscher & Laudien, 2018). Figure 1 shows this

clearly: Communication takes place between the

service providers and the users. For this, payment,

service, and information flow run between them.

Only one action takes place between the platform and

the service providers, which is the delivery of system

services. System services include the visual

representation on the marketplace platform. The

service providers pay for this service. The user and

the platform communicate restrictively by the search

function on the platform.

Applied to the “AAL care consultation” use case,

the following has to be considered. When a person

with assistant needs wants to book an AAL

consultation, they search on the platform for possible

providers offering this kind of consultation. Before

receiving the service, the interested person pays the

selected service provider directly, without the help of

the platform. After receiving the payment, the service

provider advises the person with assistance needs on

the possibilities of using digital technologies in the

home to live independently for a long time. Naturally,

interested person may also book several other

services apart from AAL consultation from different

providers.

2.3 The Brokerage Platform

Lehmann explains that brokerage platforms like

Amazon are gaining in importance (Olbrich &

Collaborative Business Model Structures for a Digital Care Platform: Value Proposition, Partners, Customer Relations, and Revenues

113

Lehmann, 2018). Brokerage platforms are

characterized by a multitude of offerings by private

and commercial providers. These include products as

well as services (Olbrich & Lehmann, 2018).

Furthermore, the brokerage platforms’ functions are

to initiate transactions and to enhance transparency in

an unclear market – in this case, the care market.

Olbrich and Lehmann further state, that a

brokerage platform has a specific value proposition

that differs from the classic marketplace platform. On

the service providers’ side, placing offerings on the

platform enhances attention on their service range and

their website. Also, service providers could use a

brokerage platform for publicity reasons (Lehmann,

2019). On the demanders’ side, a brokerage platform

offers cost-efficient access to products and services.

Lehmann also displays a few disadvantages for

service providers and demanders. Thus, for service

providers, it could be a higher time expenditure to

create advertisements. Additionally, there still exists

an information asymmetry that creates insecurity on

the demanders’ side (Lehmann, 2019).

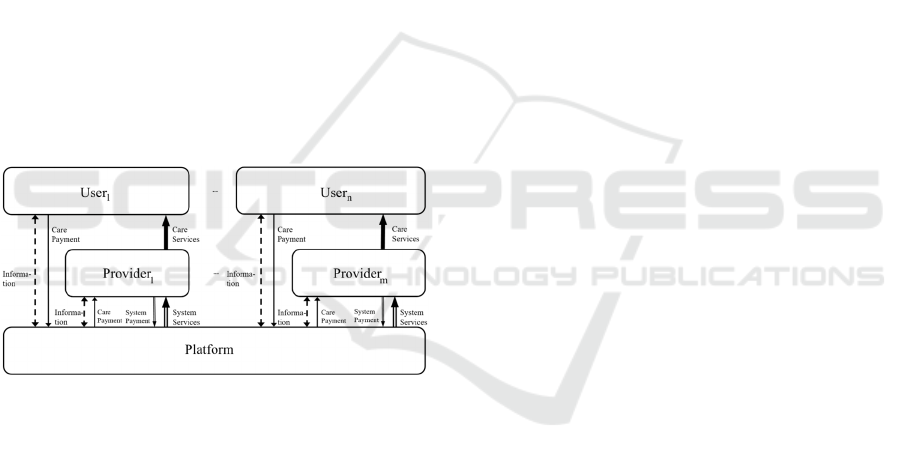

The brokerage platform differs from the

marketplace platform on several points – as

demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Brokerage Platform (Bleja, Krüger, Neumann, et

al., 2022).

Between the platform and the service providers,

there are still the system services and system

payments. Additionally, the platform pays the service

providers the care payment that they received from

the users. In this model, the user pays the platform for

the care services and not the service providers. The

platform only forwards the care payment to the

providers. The care service is the only action that

takes place between the service provider and users.

Communication, payment, and information run

through the platform.

This influences the value proposition of the

platform for the service providers and the users. By

taking over the administrative workload, the platform

can relieve the providers so that they can devote more

time to caring for and supporting users. Furthermore,

this model is less objectionable for service providers

from a data protection perspective, as the service

providers only receive the information they need from

the providers to provide a support service.

Here, the use case “AAL care consultation”

described at the beginning, is once again used for

clarification. The relationships between the players

differ in this business model from the market place

platform.

Here, interested users can initially search for an

AAL care consultation via a search mask. Once they

find a suitable service provider, the platform contacts

the service provider and exchanges information. The

person with assistance needs pays the platform for

performing the care service. The platform forwards

the payment to the service provider. The person with

assistance needs is then advised on AAL options in

their home. If further services are required, such as

the installation of AAL technologies in the home, the

platform can arrange for other suitable service

providers.

2.3.1 Collaborative Business Model

Structure

Collaborations are increasingly forming, especially in

the development of complex projects. In addition to

the sole development of products and services,

different know-how is needed, for example for

marketing, the target group-specific address, or the

user-centered orientation (Avital et al., 2014).

Collaboration is usually a continuous, trusting

cooperation of legally independent partners (Sydow,

2019). These can be composed of interdisciplinary

partners to bring different expertise to the

cooperation. However, companies from the same

fields, e.g. possibly competitors, can also collaborate

(Laycock, 2005). In most cases, collaborations are

entered into when cooperation on certain issues

appears to make sense, and advantages are hoped for

through interdisciplinary cooperation and the

exchange of ideas. Especially in the development of

innovations, there is an increasing number of

collaborations (Bleja et al., 2020; Echavarria, 2015).

Concerning the development of a care platform,

for example, several providers of care services or

products in the health and care sector and the platform

operator could collaborate to develop the care

platform and successfully launch it on the market.

Collaborations with cities and health insurance

companies would also be conceivable.

In addition to the many advantages of

collaborative alliances, the type of cooperation is also

associated with challenges. Compared to acting

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

114

alone, collaborations are associated with increased

communication and coordination efforts (Geramanis,

2020). In addition, collaborative business models

need to be developed to successfully and sustainably

establish the products and services developed within

the framework of collaboration on the market (Bleja

et al., 2020).

When looking at business models, such as the

Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur,

2010), it becomes apparent that these are usually

geared towards one company and less towards the

collaboration of several companies (Bleja et al., 2020;

Oliveira et al., 2013). To apply existing business

model structures to a collaborative merger, it is,

therefore, necessary to expand the models or develop

new business model structures (Bleja et al., 2020). In

particular, the aspect of data protection should not be

neglected in a collaborative business model. The

partners have to be considered in a differentiated way,

according to collaboration partners and additional

collaboration partners (Bleja et al., 2020; Ganz et al.,

2016).

Figure 3 describes a collaboration (see grey box)

between different providers (1, 2) and a digital

platform as well as the care services from the

providers (1, 2) for the respective users (1, 2, 3, and

4).

Figure 3: Collaboration Platform (own source).

Users book from the platform services that a

provider offers on the platform. In this example, the

providers are care service providers, and the digital

platform is a care platform, which is also the

collaboration partner. In this process, the providers

send information to the platform that is important for

allocation, for example, completing orders from the

providers for the users (1, 2, 3, and 4). This

information is forwarded by the platform along with

the “Total User Payment” for an allocation of the

efficiency gains. The allocation is now required to

fairly distribute the “Allocation Payment” for the

platform and Providers 1 and 2.

The “Total User Payment” is derived from the

“Care Payment” of the users (1, 2, 3, and 4) for the

care services of the providers (1, 2). The “Care

Payment” is routed directly to the platform to

centralize all payment receipts and ensure that the

allocation can correctly capture all revenue.

To illustrate this once, the use case “AAL care

consulation” will be referred to again. An interested

user books an AAL care consultation on the platform

that is provided by an exemplary Provider 1. Provider

1 delivers the AAL care consulation to the interested

user and submits information to the platform about

the completed service that is relevant for the

allocation. The platform collects the information as

well as the payment from the interested user and

passes it on to Allocation. The latter then provides the

“Allocation Payment” to the exemplary Provider 1

following the service.

In the figure, it is conceivable that another user

also books the AAL care consultation from Provider

1 or that exemplary Provider 2 delivers another care

service – for example domestic help – for the

userinitially interested in only an AAL care

consultation from Provider 1. There are several

possibilities, which also include other users and care

service providers, which are not mentioned here.

In Figure 3 of the collaborative business model,

providers (1, 2) and users (1, 2, 3, and 4) are used as

examples to show how such a business model could

work. However, this assumption is rather model-like

and, of course, user 4 could also book a service from

provider 1 or user 1 from provider 2. The figure is,

therefore, intended to serve as a simplification to be

able to represent the collaborative business model

more comprehensibly.

3 FINANCING AND REVENUE

MODELS

Financing is an important aspect of a business model

(Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). After an explanation

of the methodology, financing and revenue models

for a care platform are analyzed in the following

chapter.

3.1 Methodology

To identify and analyze financing and revenue

models for a care platform, an analysis of existing

Collaborative Business Model Structures for a Digital Care Platform: Value Proposition, Partners, Customer Relations, and Revenues

115

care platforms and a qualitative survey of potential

actors on a care platform were conducted in addition

to a literature review.

For the competitor analysis, the benchmark

analysis was carried out according to Fleisher and

Bensoussan (Fleisher & Bensoussan, 2015). First,

potential competitors in Germany were identified. Of

the analyzed care platforms, twelve were identified as

having a particular interest in the care platform to be

developed, based on their estimated level of

awareness. These were then further analyzed using a

catalog of criteria created for the study. This criteria

catalog consists of six topic areas and contains a total

of over 50 criteria.

With the help of the analysis, the offers, the value

proposition, the channels for addressing customers as

well as financing and revenue models of care

platforms were to be recorded and analyzed. The data

collection took place on the individual websites of the

platforms themselves and was partly supplemented

by corresponding press articles, project reports, and

the social media presence of the platforms. The aim

was to work out which needs in the care sector still

exist on the provider and demand-side and are not

covered by existing platforms. Consequently, the aim

was to work out the added value that the care platform

to be developed can offer providers and consumers on

the platform compared to potential competitors (Bleja

et al., 2021; Bleja, Krüger, & Grossmann, 2022).

After the competitor analysis, a qualitative

analysis was carried out. For this purpose, potential

providers were methodically interviewed on a care

platform with the help of qualitative guideline-based

expert interviews (Bleja et al., 2021; Bleja, Krüger, &

Grossmann, 2022). In expert interviews, the focus is

not on the interviewees themselves, but on the topic

area, e.g. the work context the experts represent

(Nohl, 2017).

In addition to the analysis of financing and

revenue models, the qualitative analysis was to be

used to identify needs and wishes regarding a care

platform from the perspective of potential users and

providers. For this purpose, a guideline was first

created. Methodically, the SSP principle of guideline

creation according to Helfferich (Helfferich, 2011,

2019) was used for this. The guide consists of 32

questions from eight categories and was tested before

the expert interviews with the help of pre-interviews

(Bleja et al., 2021; Bleja, Krüger, & Grossmann,

2022).

Due to the time restrictions of the research

project, the experts were selected using selective

sampling. The experts could be potential providers on

a care platform and represent as many different

subject areas as possible. This provides the most

diverse expertise and perspectives to be included in

the study. To involve the perspectives of potential

users in the analysis, the experts needed to be in

regular contact with people with assistance needs and

their relatives.

A total of 15 experts from the fields of Care

Services, Health and Nursing Care Companies,

Volunteer Organizations, Seniors Representatives,

Care, and Social Counselling, Housing Consulting,

Financial Service Providers, and Mail-order

Pharmacies were interviewed (see figure 4) (Bleja et

al., 2021; Bleja, Krüger, & Grossmann, 2022).

Figure 4: Composition of the Sample (Bleja, Krüger, &

Grossmann, 2022).

Except for one interview, which took place via

video, the interviews were conducted face-to-face at

the experts’ premises and recorded using a dictation

machine. All interviewed experts agreed to the audio

recording and signed a consent form prepared for this

purpose. The interview length was between 45 and 60

minutes (Bleja et al., 2021; Bleja, Krüger, &

Grossmann, 2022). The interviews were methodically

evaluated with the help of content analysis according

to Gläser and Laudel (Gläser & Laudel, 2010). The

MAXQDA software was used for this purpose.

3.2 Results

The interviewees of the qualitative analysis believed

that the prices for persons with assistance needs as

well as their relatives should be kept as low as

possible. At best, the platform should even be free to

use. The result is also reflected in the analysis of other

care platforms, which are all free of charge for users.

Some respondents to the qualitative research also

stated that it was common for service providers to pay

a small annual fee depending on, for example, annual

turnover. In addition, commission models could be

considered financing models.

Other financing options addressed during the

interviews included public funding, subsidies from

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

116

private or statutory insurers (long-term care, pension,

accident insurance), the digitization fund of the

statutory health insurance, and also financing via

advertisements. In terms of advertising, however,

some of the interviewees advised not to place too

much advertising so as not to raise any doubts about

the independence of the platform. Overall,

respondents identified financing as one of the most

complicated aspects of a care platform. At the same

time, financing is very important for the success of

the care platform.

Based on literature analysis, a variety of other

financing options for a care platform could be

identified in addition to the financing options already

mentioned for the platform via commercial

advertising (e.g., in the form of banner ads) and via

contributions from users (subscriptions) or providers

(offer fees, brokerage, and sales provision). For

example, it could also be suitable for a care platform

to use a so-called freemium model (Grothus et al.,

2021a; Li et al., 2020). In this case, the basic version

of the platform is offered to users free of charge so

that they can try it out first. If needed, users can

additionally subscribe to a paid premium version,

which provides them with further benefits. In

addition, revenue could be generated through the

collection and processing of user data by using it

internally or passing it on to third parties (leverage

customer data) (Grothus et al., 2021a). However,

financing the platform by selling data was considered

critical by the interviewees in the qualitative analysis

conducted.

Pay-per-use models could also be considered for

the use of certain services by users, such as

consulting, or by providers, such as customer data

management. Accordingly, payment would be based

on the pure duration of use of certain services

(Grothus et al., 2021a; Wirtz & Ullrich, 2008).

In addition, financing through donations,

subsidies from health and long-term care insurers,

and local authorities could be considered. In this

context, social impact bonds could also be

conceivable as financing models. Social impact bonds

are cooperative ventures in which one or more social

service providers, charitable foundations, or private

investors, and the state participate. The target group,

the goal, the key success criteria, and the financial

framework are contractually defined in advance. In

the first step, the investors or foundations provide

financing. If the agreed targets are achieved, the state

assumes the costs and, if applicable, also a target

achievement premium payment (Fölster, 2017; Hulse

et al., 2021; Katz et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2015).

In addition to grants and donations, crowdfunding

is also an option for developing and building the

platform (Grothus et al., 2021a; Wirtz & Ullrich,

2008). For example, the platform ReCare, which is

also active in the healthcare sector, secured part of its

funding via crowdfunding (Thieme Verlag, 2021). In

crowdfunding, a product or project is financed by

many investors. If a predefined budget is achieved,

then the project is realized (Grothus et al., 2021a;

Wirtz & Ullrich, 2008).

Grothus, Thesing and Feldmann, conclude that

innovative business models are often characterized by

a combination of different financing and revenue

models (Grothus et al., 2021b).

It can be stated that the financing of a care

platform represents an important aspect of the

business model, but also a major challenge for the

platform operators. This is also shown by the results

of the studies, where financing was identified as one

of the most critical aspects of the business model

(Bleja et al., 2021).

On the one hand, this is due, among other things,

to the fact that the use of many websites and apps is

free for users (Scherenberg, 2015). Accordingly, the

willingness to spend money for this on the part of the

users is low. On the other hand, care service providers

in Germany currently have a surplus of demand

(Jacobs et al., 2021), so they are not forced to offer

their services additionally via care platforms.

Consequently, the willingness of providers of

products and services to spend money for a presence

on an online platform is also rather low. For this, the

value proposition of the users and providers should be

identified in detail. Only if the users and/or providers

have visible added value through the platform does

this have a positive effect on their willingness to pay.

4 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

WORK

For the new development of a care platform, it must

offer added value to existing solutions, ideally for the

providers on the platform as well as for the users.

Accordingly, the platform has to be developed with

the stakeholders as far as this is possible, e.g. with the

help of a human-centered design approach. Both a

brokerage and a marketplace platform are

conceivable, each with different structures.

Furthermore, the financing of the platform was

identified in the qualitative expert interviews as an

important aspect of the long-term implementation of

the care platform on the market. A variety of revenue

Collaborative Business Model Structures for a Digital Care Platform: Value Proposition, Partners, Customer Relations, and Revenues

117

models are available for this, which can also be

combined. The competitor analysis and the

qualitative analysis both conclude that financing the

platform is realistic, via the providers above all.

Especially in the care sector, there is currently a

surplus of demand, so the providers of care services

and products are not dependent on a care platform to

generate orders. Accordingly, the challenge beyond

generating offers is to achieve further added value for

the providers so that they are willing to pay for it. For

example, another focus of the platform could be to

reduce the administrative burden for providers.

If a platform is to be developed and brought on

the market by collaborative partners, the allocation

aspect poses a challenge. The costs and revenues

generated by the platform need to be fairly distributed

among the collaborative partners afterward. However,

especially if the revenues were generated together and

the partners cooperate on one level, a decision support

system based on solution approaches of cooperative

game theory is needed to distribute the costs and

revenues. Based on the results presented,

collaborative business model structures for a care

platform will be developed and a decision support

system for the distribution of costs and revenues

among the collaboration partners.

REFERENCES

Avital, M., Leimeister, J. M., & Schultze, U. (2014). ECIS

2014 proceedings: 22th European Conference on

Information Systems ; Tel Aviv, Israel, June 9-11, 2014.

http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2014/

Bartels, K., Beck, S., Buchholz, B., Bürger, M., & Straub,

S. (2020). Kollaborative Wertschöpfungssysteme in der

Industrie: Geschäftsmodellentwicklung und rechtliche

Fragen. Berlin. Institut für Innovation und Technik in

der VDI / VDE Innovation + Technik GmbH.

Björkdahl, J. (2009). Technology cross-fertilization and the

business model: The case of integrating ICTs in

mechanical engineering products. Research Policy,

38(9), 1468–1477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.20

09.07.006

Bleja, J., Krüger, T., & Grossmann, U. (2022).

Development of a Holistic Care Platform - A User-

Centered Approach. In T. Ahram & R. Taiar (Eds.),

Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems: Vol. 319.

Human Interaction, Emerging Technologies and

Future Systems V (Vol. 319, pp. 378–385). Springer

International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

3-030-85540-6_49

Bleja, J., Krüger, T., Neumann, S., Engelmann, L., &

Grossmann, U. (2022). Development of a Holistic Care

Platform in the Smart City Environment: Implications

for Business Models and Data Usage Concepts [in

print]. IEEE European Technology and Engineering

Management Summit 2022 (E-TEMS), pp. 1–6.

Bleja, J., Wiewelhove, D., Grossmann, U., & Morz, E.

(2020). Collaborative Business Model Structures for

Wireless Ambient Assisted Living Systems. In 2020

IEEE 5th International Symposium on Smart and

Wireless Systems within the Conferences on Intelligent

Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems

(IDAACS-SWS) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. https://doi.org/

10.1109/IDAACS-SWS50031.2020.9297108

Bleja, J., Wiewelhove, D., Krüger, T., & Grossmann, U.

(2021). Achieving Life in Smart Cities: Chances and

Challenges for a Holistic Care Platform. IEEE

European Technology and Engineering Management

Summit 2021 (E-TEMS), pp. 72–75.

Bullinger, H.‑J., Neuhuttler, J., Nagele, R., & Woyke, I.

(2017). Collaborative Development of Business

Models in Smart Service Ecosystems. 2017 Portland

International Conference on Management of

Engineering and Technology (PICMET), 2017, pp. 1–9.

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business Model Innovation:

Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Planning,

43(2-3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.

07.010

Echavarria, M. (2015). Enabling Collaboration: Achieving

Success Through Strategic Alliances and Partnerships.

LID Publishing Inc.

Fleisher, C. S., & Bensoussan, B. E. (2015). Business and

competitive analysis: Effective application of new and

classic methods (2. ed.). Pearson.

Fölster, S. (2017). Viral mHealth. Global Health Action,

10(sup3), 1336006. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.

2017.1336006

Ganz, W., Kramer, J., Rößner, A., Eymann, T., & Völkl, A.

(2016). Entwicklung von Geschäftsmodellen für

Dienstleistungsnetzwerke im Gesundheitsbereich. In M.

A. Pfannstiel, C. Rasche, & H. Mehlich (Eds.),

Dienstleistungsmanagement im Krankenhaus (pp. 25–

46). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-08429-5_2

Geramanis, O. (2020). Zusammenarbeit 5.0 – die

kooperative Dimension der neuen Arbeitswelt. In O.

Geramanis & S. Hutmacher (Eds.), uniscope.

Publikationen der SGO Stiftung. Der Mensch in der

Selbstorganisation (pp. 3–25). Springer Fachmedien

Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27048-

3_1

Gläser, J., & Laudel, G. (2010). Experteninterviews und

qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente

rekonstruierender Untersuchungen (4. Auflage). VS

Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Grothus, A., Thesing, T., & Feldmann, C. (2021a).

Geschäftsmodell-Innovationen im Bereich Mixed

Reality. In A. Grothus, T. Thesing, & C. Feldmann

(Eds.), Digitale Geschäftsmodell-Innovation mit

Augmented Reality und Virtual Reality (pp. 53–75).

Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-63746-3_4

Grothus, A., Thesing, T., & Feldmann, C. (2021b).

Geschäftsmodell-Innovationen: Wert für den Kunden

ICSBT 2022 - 19th International Conference on Smart Business Technologies

118

und Erträge für das Unternehmen. In A. Grothus, T.

Thesing, & C. Feldmann (Eds.), Digitale

Geschäftsmodell-Innovation mit Augmented Reality

und Virtual Reality (pp. 43–51). Springer Berlin

Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-63746-

3_3

Helfferich, C. (2011). Die Qualität qualitativer Daten:

Manual für die Durchführung qualitativer Interviews (4.

Auflage). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Helfferich, C. (2019). Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews.

In N. Baur & J. Blasius (Eds.), Handbuch Methoden der

empirischen Sozialforschung (pp. 669–684). Springer

Fachmedien.

Hulse, E. S. G., Atun, R., McPake, B., & Lee, J. T. (2021).

Use of social impact bonds in financing health systems

responses to non-communicable diseases: Scoping

review. BMJ Global Health, 6(3).

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004127

Jacobs, K., Kuhlmey, A., Greß, S., Klauber, J., &

Schwinger, A. (2021). Pflege-Report 2021. Springer

Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-

63107-2

Katz, A. S., Brisbois, B., Zerger, S., & Hwang, S. W. (2018).

Social Impact Bonds as a Funding Method for Health

and Social Programs: Potential Areas of Concern.

American Journal of Public Health, 108(2), 210–215.

https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304157

Kimble, C. (2015). Business Models for E-Health:

Evidence From Ten Case Studies. Global Business and

Organizational Excellence, 34(4), 18–30.

https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21611

Laycock, M. (2005). Collaborating to compete: Achieving

effective knowledge sharing in organizations. The

Learning Organization, 12(6), 523–538.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470510626739

Lehmann, N. (2019). Verkauf über Vermittlungs-

plattformen. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-25598-5

Li, Z., Nan, G., & Li, M. (2020). Advertising or Freemium:

The Impacts of Social Effects and Service Quality on

Competing Platforms. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 67(1), 220–233.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2018.2871420

Marquardt, K. (2017). Smart services – characteristics,

challenges, opportunities and business models.

Proceedings of the International Conference on

Business Excellence, 11(1), 789–801.

https://doi.org/10.1515/picbe-2017-0084

Memon, M., Wagner, S. R., Pedersen, C. F., Beevi, F. H.

A., & Hansen, F. O. (2014). Ambient assisted living

healthcare frameworks, platforms, standards, and

quality attributes. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 14(3),

4312–4341. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140304312

Mukhopadhyay, S., & Bouwman, H. (2018). Multi-actor

collaboration in platform-based ecosystem:

opportunities and challenges. Journal of Information

Technology Case and Application Research, 20(2), 47–

54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228053.2018.1479160

Nohl, A.‑M. (2017). Narrativ fundierte Interviews. In A.-M.

Nohl (Ed.), Interview und Dokumentarische Methode

(pp. 15–28). Springer Fachmedien.

Olbrich, R., & Lehmann, N. (2018). Erfolgsfaktoren für den

Verkauf über Vermittlungsplattformen: Success

Factors for Sales via Intermediation Platforms.

Marketing: ZFP–Journal of Research and Management,

40(1), 48–62.

Oliveira, A. I., Ferrada, F., & Camarinha-Matos, L. M.

(2013). An approach for the management of an AAL

ecosystem. In 2013 IEEE 15th International

Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and

Services (Healthcom 2013). IEEE.

https://doi.org/10.1109/healthcom.2013.6720747

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business Model

Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game

Changers, and Challengers (1st ed.). John Wiley &

Sons Incorporated. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/

lib/kxp/detail.action?docID=581476

Scherenberg, V. (2015). Qualitätsaspekte von Gesundheits-

Apps: Wie lässt sich Qualität erkennen? Public Health

Forum, 23(3), 144–146. https://doi.org/10.1515/

pubhef-2015-0053

Schwarting, G. (2018). Demografischer Wandel. Nomos

Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845295879

Sydow, J. (2019). Managing inter-organizational

collaborations: Process views. Research in the

Sociology of Organizations Ser: v. 64. Emerald

Publishing Limited. https://search.ebscohost.com/

login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nl

abk&AN=2157431

Täuscher, K., & Laudien, S. M. (2018). Understanding

platform business models: A mixed methods study of

marketplaces. European Management Journal, 36(3),

319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.06.005

Teece, D. J. (2010). Business Models, Business Strategy

and Innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 172–

194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

Thieme Verlag (2021). Digitales Entlassmanagement –

Recare erhält Finanzierung in Höhe von zwei Millionen

Euro. Gesundheitsökonomie & Qualitätsmanagement,

26(01), 23–24. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1347-6134

Wilson, K. E., Silva, F., & Ricardson, D. (2015). Social

Impact Investment: Building the Evidence Base.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2562082

Wirtz, B. W., & Ullrich, S. (2008). Geschäftsmodelle im

Web 2.0 — Erscheinungsformen, Ausgestaltung und

Erfolgsfaktoren. HMD Praxis Der Wirtschafts-

informatik, 45(3), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/

BF03341209

Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2010). Business Model Design: An

Activity System Perspective. Long Range Planning,

43

(2-3), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.20

09.07.004.

Collaborative Business Model Structures for a Digital Care Platform: Value Proposition, Partners, Customer Relations, and Revenues

119