An Online Randomised Controlled Trial of the Positive Confiding to

Improve Emotional Wellbeing in Nurses during the COVID-19

Pandemic: A Protocol Study

Cui Lu

1,2,3 a

, Yi Tang

4,5 b

and Tianyong Chen

1,2,* c

1

Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

2

Department of Psychology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

3

Emergency Department, TEDA Hospital, Tianjin, China

4

Department of Neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Beijing, China

5

National Center for Neurological Disorders, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Keywords: Online Intervention, Depression, Confiding, Well-Being, Emotion.

Abstract: In the time of COVID-19 pandemic, nurses suffering from stress and depression. Meanwhile, previous

studies indicated that the psychological well-being of medical staff benefited from confiding. However,

hitherto there is no experimental evidence supporting the implementation of confiding for nurses to

optimize their emotional outcome. Based on previous studies and the background of positive psychological,

we creates the “positive confiding intervention”, which means asking participants to consider the social

support or positive meaning gaining from expericence of confiding occupational hassles weekly. An online

two group randomised controlled trial design will be used in this study. We will use random grouping

method. A control group and a “positive confiding intervention” group will comprise 100 eligible

participants in total. The expected result is that the “positive confiding intervention” will significantly

improve nurses’ positive affect, interpersonal emotion regulation, perceived social support and cognitive

reappraisal, as well as decrease negative affect and depression.

1 INTRODUCTION

1

Amount of studies revealed that nurses face

extraordinary stresses in the medical environment

which can lead to choronic burnout (Cohen-Katz

2004, Happell 2013, Dall'Ora, 2020) and damage

nurses’ emotional wellbeing (Huang 2018, Boyle

2018, Boyle,2021), especially in the time of the

COVID-19 pandemic (Sanliturk 2021, Murat 2020).

Several systematic reviews reported that, in time of

the COVID-19 pandemic, quite a few of healthcare

workers’ suffering from stress, anxiety, depression

and sleep disturbance (Salari 2020a, Salari 2020b,

Sahebi 2021, Maqbali 2021, Marvaldi 2021).

Especially, it was reported that, during the time of the

COVID-19 epidemic, the prevalence of sleep

disturbance, anxiety and depression respectively

were 43%, 37% and 35% (Maqbali 2021). Therefore,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8943-2202

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8052-065X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8948-4969

improving nurses’ emotional wellbeing will be an

important intervention goal, which would also benefit

patients’ caring (Di Muzio 2019, Giorgi 2018).

As a wide reach and low cost intervention with

high ecological validity, confiding to others maybe

an effective strategy for improving nurses’ emotional

wellbeing. It was found that, 79.3% medical staff

would confide their troubles to others (Liu 2020), and

comparing to confiding troubles to others, never

confiding troubles to others was associated with

medical staff’s self-reported anxiety (OR=2.2) and

depression (OR=2.0) under the COVID-19 epidemic

(Liu 2020). This result is consistent with a study

based on a big sample of 123,794 adults, which

revealed that the most protective factors for

depression are frequency of confiding in others

(adjusted OR=0.85) (Choi 2020). Previous studies

has indicated that, confiding is conducive to people’s

psychological well-being (Choi 2020, Slepian 2018,

Eldridge 2020, Pennebaker 1997), and medical staff

also benefits from confiding (Liu 2020). However,

hitherto there is no experimental evidence supporting

Lu, C., Tang, Y. and Chen, T.

An Online Randomised Controlled Trial of the Positive Confiding to Improve Emotional Wellbeing in Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Protocol Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0011212200003438

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Health Big Data and Intelligent Healthcare (ICHIH 2022), pages 37-42

ISBN: 978-989-758-596-8

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

37

the implementation of confiding for nurses to

optimize their emotional outcome.

Confiding means disclose one’s own personal

experience including emotions, attitudes or opinions,

to others. The need of confiding is universal. Humans

have the urge to to confide, and will release stress by

confiding (Eldridge 2020, Kant 1963, Smith 2002).

Confiding has remained an important component of

many forms of psychotherapy (Kelly 1996). A

previous study showed that, as for women, their

reasons for not confiding were unsupportive social

interactions and lack of social support, and they

tended to confide to their family and friends instead

of health workers, (Figueiredo 2010). In real life,

decisions of whether to confide hassles to others are

personal, and individuals pick and choose both what

information they share and with whom they share it.

There are several frameworks contextualizing

decisions of disclosure (or confiding), such as the

Communication Privacy Management Theory, the

Disclosure Processes Model, the Health Disclosure

Decision-Making Model and the Revelation Risk

Model. These frameworks above reflect the

agreement that the decision of whether to confide

private information depend on the advantages and

disadvantages (Afifi 2020). Many factors influence

the effects of confiding on well-being, including “the

type of relationship, the valence of the stressor, the

response to the disclosure, and the meaning

generated from the disclosure” (Slepian 2018, Afifi

2020). In literature (Eldridge 2020, Pennebaker 1997,

Lu 2019, Howell 2009), several positive meanings of

confiding were mentioned: 1) confiding helps to

form and develop interpersonal relationships; 2)

people can benefit from confiding by co-regulating

emotional experiences; 3) confiding can help people

co-construct meanings, as well as affirm, challenge

and develop their identity; 4) future social support

can be positively shaped; 5) By confiding, people

may could receive others’ concrete aid; 6) Confiding

may help people get more message about others’

feels about similar things, and people can compare

and learn others’ emotion regulation strategy.

In short, the main benefit of confiding is helping

confider receive social support. According to Kahn

and Antonucci (Kahn 1980), “there are three types of

social support or support exchanges: aid, affect, and

affirmation”. Aid means tangible assistance,

including providing money or sick care, information

and advice. Affect means emotional support,

including perceived love, care, fondness or affection

of others. Finally, affirmation is the intangible

communication to another convoy member that

members share or respect the same values, goals, and

aspirations. Additionally, many studies indicated

that, perceived support is more helpful than received

support (Santini 2015). So, it is important that people

would perceive the social support they can benefit

from confiding, which is an active and positive

behavioral model. As a recent study reported that,

confiding predicts higher well-being through framing

confiding as a source of social support (Slepian

2018).

From the perspective of Interpersonal Emotion

Regulation, Rimé (2007) argues that emotional

episodes are virtually always followed by long-term

congnitive and social effects, and particularly

individul emtional experiences elicit important social

behaviors by which the actor informs his or her

socical partner of what happened and shares with

them related thoughts and feelings. It was expounded

that (Rimé 2007), people who share positive

emotions may make their positive effect and social

bonds improve. For negative emotional experience,

people would tolerate the reexperience involved in

social sharing because of the final benefit it provides

them (Rimé 2007). It was concluded that there are

three classes of regulation needs, including

sociaffective needs, congnitive needs and action

needs (Rimé 2007). It was reported that the reasons

for sharing negative emotion was socioaffective

motives, including receiving support, validation and

comfort (Rimé 2007). As an integrative review

argues that interpersonal emotion regulation may

decrease depression through improving perceived

social support (Marroquín 2011).

Above all, similar to positive psychology’s use of

research on the “Three Good Things Intervention”

and the “Meaning-Oriented Interventions” (Parks

2004), we created the “positive confiding

intervention”, which means asking partcipants to

consider the social support or positive meaning

gaining from expericence of confiding occupational

hassles and record the positive meanings gaining

from the most satisfied confiding experiences

weekly. In light of the Handbook of Positive

Psychological Interventions, by participating online

positive psychological interventions may make

people be more willing to manage of their own heath,

because online interventions provide methods to

enlighten their behaviour, thinking, and interpersonal

interaction (Parks 2004). Therefore, we are going to

conduct the “positive confiding intervention” by

online techniques.

ICHIH 2022 - International Conference on Health Big Data and Intelligent Healthcare

38

2 STUDY PURPOSES

This study aims to test the efficacy of our created

“positive confiding intervention” to improve nurses’

emotional wellbeing, including improving nurses’

positive affect, interpersonal emotion regulation,

perceived social support and cognitive reappraisal,

as well as decrease negative affect and depression.

3 METHODS/DESIGN

3.1 Design and Participants

The study has received ethical approval from the

Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology,

Chinese Academy of Sciences. A two group

randomised controlled trial design will be used in

this study. The G*Power 3.1 (Faul 2007) was used

to estimate the required number of participants (see

Table 1). As seen in Table 1, the required overall

number of participants is 45, which can guarantee

enough sample size for detecting an effect.

Table 1 Sample size estimated by G*Power 3.1.

Input paramete

r

s Output

p

aramete

r

s

Effect size

d

0.5

α err

p

rob 0.05

Power (1-β err prob) 0.95

Number of

g

rou

p

s 2

Noncentrality parameter

λ

3.35

t value 1.68

d

f 44

Total sam

p

le size 45

p

owe

r

0.95

We decide to improve the number of participants

to 100 participants (see Table 2). Nurses aged 18-55

years old, working in domestic public hospitals in

China, won't leave this job during the study period.

Table 2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria

Nures aged between

18 and 60 years ol

d

Cannot grantee completing

this stud

y

Working in domestic

public hospitals in

China

Participating in other

similar psychological

studies

Won't leave this job

during the study

p

erio

d

Taking a long vacation

during the study period

Do not need to take care of

patients during working

time

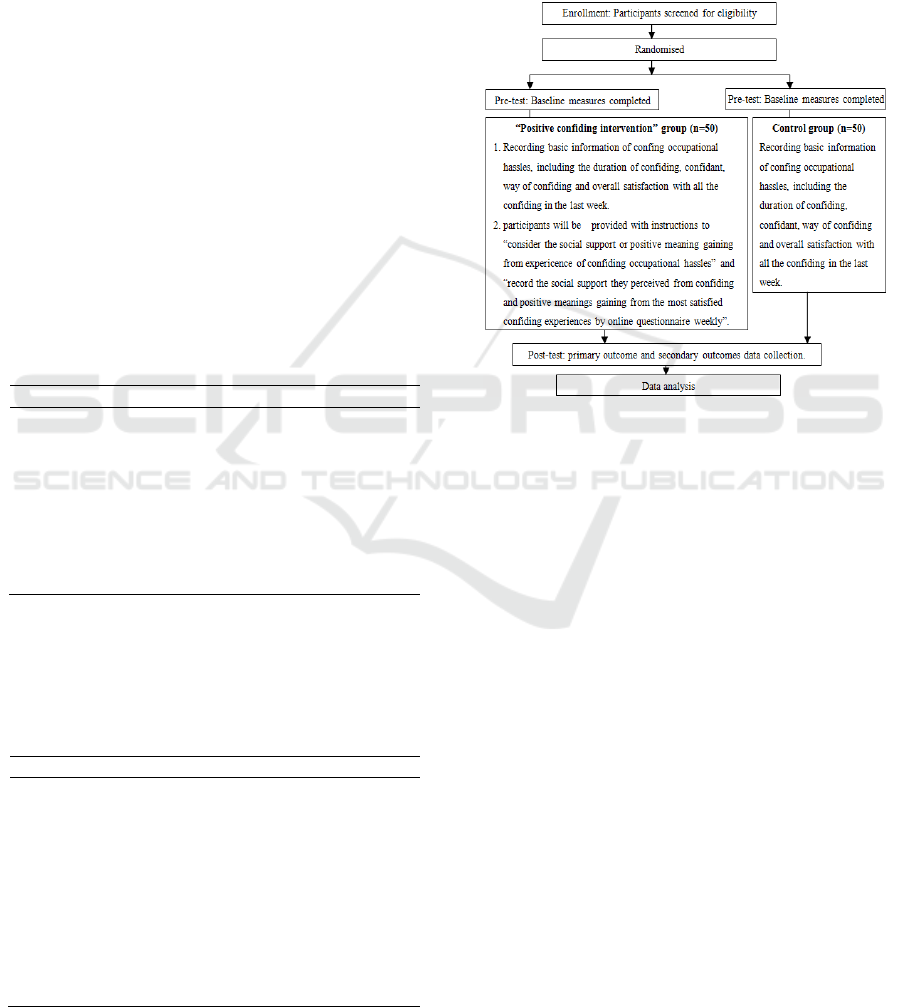

3.2 Randomisation and Allocation

After completing all the baseline measures, all the

participants will be randomly grouped, which means

all the objects will participate in the “positive

confiding intervention” group or control group

randomly (see Figure 1). We will use a computer

program to generate an allocation sequence, which

will be used for random allocation.

Figure 1: Flow chart of trial procedure.

In the “positive confiding intervention” group,

participants will be provided with instructions to

“consider the social support or positive meaning

gaining from expericence of confiding occupational

hassles” and record the social support they perceived

from confiding, and record positive meanings

gaining from the most satisfied confiding

experiences by online questionnaire weekly. In the

online questionnaire, participants will be asked to

think about how much social support[28] or positive

meaning they have perceived, including: 1) concrete

help for solving problems, advice for solving

problems and information helping promote

understanding; 2) emotional support including

enhancing eomtional connection, helping improve

positive emotion or decreasing negative emotion, 3)

feeling validated or supported, promote understand

or endorse of self and increase affirmation of

professional value. In the online questionnaire for

control group, only the basic information of

confiding occupational hassles will be involved,

including the duration of confiding, confidant, ways

of confiding and overall satisfaction with all the

confiding in the last week, the same as in the

“positive confiding intervention” group.

An Online Randomised Controlled Trial of the Positive Confiding to Improve Emotional Wellbeing in Nurses during the COVID-19

Pandemic: A Protocol Study

39

4 DATA COLLECTION AND

OUTCOME MEASURES

4.1 Background Information

Demographic data, socioeconomic status,

occupational status and health condition will be

collected before intervention. Demographic data

includes age, gender, marital status, and nuber of

childern. Socioeconomic status includes education

background and if there is difficulty in paying bills,

saving money, having enough pocket money every

month. Occupational status includes working years

as a nurse, professional title and whether participate

work in shift work. Health condition includes

perceived overall health condition, perceived overall

sleep quality in the past one month.

4.2 The Primary Outcome Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) is used to

assesse depression, consists 9 items and rated with

four-point degrees according to symptom in the past

two weeks (Kroenke 2004).

The simple positive and negative affect scale

(PANAS-S) is a 12-item likert-style (4-point) rating

scale that assesses affect by situation or persistent

affect. For each item, a four-point degrees of the

scale was used to assess the frequency arise in the

past week (0=never; 1= once in a while; 2=

sometimes; 3= often; 4=always). Thereinto, 8 items

are express positive affect, and 4 items express

negative affect. Higher scores means more positive

or negative affect (Kahneman 2004).

Nurses Work Stressors Scale (NWSS) is a is a

35-item likert-style (4-point) rating scale that

assesses nurses’ source of occupational stress.

Higher scores means more work stress (Li 2000).

4.3 The Secondary Outcome Measures

The Interpersonal emotion regulation Questionaire

(IERQ) consists 20 items, which use a 5-point likert-

style rating scale to assesse how people regulate

their emotions by using others (Hofmann 2016). For

each item, a five-point degrees of the scale was used.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social

Support (MSPSS) consists 12 items, which measures

how many social support people can feel. For each

item, a 7-point degrees of the scale was used.

(Dambi 2018).

The emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ) is

used to assesse cognitive reappraisal and expressive

suppression, which consists 10 items. For each item,

a 7-point degrees of the scale was used. (Gross

2003).

The Table 3 shows all the measures used in this

study, and the time-points of measurement have

been presented too.

5 DATA ANALYSES

5.1 Primary Analyses

We will use descriptive statistics to summarize the

characteristics of all the participants, and analyse the

primary and secondary outcome measures by using t

test with a between subject factor of intervention

condition and a within-subject. Besides, we will use

effect sizes (Cohen’s d) (Cohen 1988) to illustrate

differences in all the measured results between the

before and after the intervention.

Table 3 Timeline for data collection.

Measure-

ment

time-

point

Measures

PHQ-9 PANAS IERQ

MSP

SS

NW

SS

Basline

× × × × ×

1 weeks

×

2 weeks

× ×

3 weeks

×

4 weeks

× ×

5 weeks

×

6 weeks

× ×

7 weeks

×

8 weeks

× × × × ×

6 CONCLUSIONS

Accumulating evidence indicated that nurses

confronted a lot of stress, anxiety, depression

(Salari

2020a, Salari 2020b, Sahebi 2021, Maqbali 2021,

Marvaldi 2021)

. As an important component of many

forms of psychotherapy (Kelly 1996), confiding is

also highly common among laypersons. However,

hitherto there is no experimental evidence

supporting the implementation of confiding for

nurses to optimize their emotional outcome.

Empirical research has highlighted the harm of

repress the need of confiding, as well as a lot of

benefits of confiding. However, some harm of

ICHIH 2022 - International Conference on Health Big Data and Intelligent Healthcare

40

confiding also has been put forward (Kelly 1996,

Slepian 2018). To explore the effective model of

confiding, this study creates the “positive confiding

intervention” based on previous studies and will

conduct an online randomised controlled trial to

exam its effect for promoting emotional wellbeing

by comparing the “positive confiding intervention”

with control group. The expected result is that the

“positive confiding intervention” will significantly

improve nurses’ positive affect, interpersonal

emotion regulation, perceived social support and

cognitive reappraisal, as well as decrease negative

affect and depression. will significantly improve

nurses’ positive affect, decrease negative affect and

depression, and the mediating variables of these

effect will be interpersonal emotion regulation,

perceived social support and cognitive reappraisal.

This study will build on suggestions from

previous studies that confiding tends to promote

mental well-being. Our study firstly developed the

“positive confiding intervention” as an effective

confiding for nurses to improve emotional wellbeing

innovatively, which is a wide rich and low cost

intervention with high ecological validity. By

examing the effect of this “positive confiding

intervention” on nurses, this study would further

discuss the precise mechanism through how this

“positive confiding intervention” promots nurses’s

emotional wellbeing. This study will contribute to

build an effective psychotherapy method applying to

nurses. In addition, this study will encourage people

to positively confiding, which will also contribute to

the study of social support from the perpective of

positvely constructing social support.

FUNDING

The National Key Research and Development

Program of China supports this study

(2017YFC1310102).

REFERENCES

Afifi, W.A., Afifi, T.D. (2020). The relative impacts of

disclosure and secrecy: the role of (perceived) target

response. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2020,31:94-

98.

Boyle, D.A., Bush, N.J. (2018). Reflections on the

Emotional Hazards of Pediatric Oncology Nursing:

Four Decades of Perspectives and Potential. Journal of

Pediatric Nursing, 40,63-73.

Boyle, D.A., Steinheiser, M.M. (2021). Emotional

Hazards of Nurses' Work: A Macro Perspective for

Change and a Micro Framework for Intervention

Planning. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 2(44),78-93.

Cohen-Katz, J., Wiley, S.D., Capuano, T., et al. (2004).

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on

Nurse Stress and Burnout: A Quantitative and

Qualitative Study. Holistic Nursing Practice.

18(6),302-308.

Choi, K.W., Stein, M.B., Nishimi, K.M., et al. (2020). An

Exposure-Wide and Mendelian Randomization

Approach to Identifying Modifiable Factors for the

Prevention of Depression. Am J Psychiatry.

177(10),944-954.

Dall'Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M., et al. (2020). Burnout in

nursing: a theoretical review. Human Resources for

Health. 18(1),41.

Di Muzio, M., Dionisi. S., Di Simone, E. et al (2019). Can

nurses' shift work jeopardize the patient safety? A

systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

23(10),4507-4519.

Dambi, J.M., Corten, L., Chiwaridzo, M. (2018). A

systematic review of the psychometric properties of

the cross-cultural translations and adaptations of the

Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale

(MSPSS). Health Qual Life Outcomes.16(1):80.

Eldridge, J., John, M., Gleeson, K. (2020). Confiding in

others: exploring the experiences of young people who

have been in care. Adoption & Fostering. 44(2),156-

172.

Figueiredo, M.I., Fries, E., Ingram, K.M. (2010). The role

of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social

interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients.

Psycho-Oncology. 13(2),96-105.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.G. (2007). G*Power 3: a

flexible statistical power analysis program for the

social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav

Res Methods. 39(2),175–191.

Giorgi, F., Mattei, A., Notarnicola, I., et al. (2018). Can

sleep quality and burnout affect the job performance of

shift-work nurses? A hospital cross-sectional study. J

Adv Nurs. 74(3),698-708.

Gross, J.J., John, O,P. (2003). Individual differences in

two emotion regulation processes: implications for

affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology. 85(2),348-362.

Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the

behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

New Jersey.

Happell, B., Dwyer, T., Reid-Searl, K., et al. (2013).

Nurses and stress: recognizing causes and seeking

solutions. Journal of Nursing Management. 21(4),638-

647.

Huang, CL., Wu, MP., Ho, CH., et al. (2018). Risks of

treated anxiety, depression, and insomnia among

nurses: A nationwide longitudinal cohort study. PloS

one.13(9), e0204224.

Howell, E.A., Mora, P.A., DiBonaventura, M.D. (2009).

Modifiable factors associated with changes in

An Online Randomised Controlled Trial of the Positive Confiding to Improve Emotional Wellbeing in Nurses during the COVID-19

Pandemic: A Protocol Study

41

postpartum depressive symptoms. Arch Women’s

Ment Health. 12, 113-120.

Hofmann, S.G., Carpenter, J.K., Curtiss, J. (2016).

Interpersonal Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

(IERQ): Scale Development and Psychometric

Characteristics. Cognit Ther Res.40(3),341-356.

Kelly, A.E., Mckillop, K.J. (1996). Consequences of

revealing personal secrets. Psychological Bulletin.

120(3),450-465.

Kant, I., 1963. Lectures on Ethics. Indianapolis, Hackett.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B. (2004). The

PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity

measure. J Gen Intern Med.16, 606-13.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A.B., Schkade, D.A. (2004). A

Survey Method for Characterizing Daily Life

Experience: The Day Reconstruction Method. Science.

306, 1776-1780.

Kahn. R.L., Antonucci, T.C. 1980. Convoys over the life

course: attachment, roles, and social support. Life-

span development and behavior. 3.

Liu, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, N., et al. (2020). Anxiety and

depression symptoms of medical staff under COVID-

19 epidemic in China. J Affect Disord. 278,144-148.

Lu, Y., Pan, T., Deng, S. (2019). What Drives Patients

Affected by Depression to Share in Online Depression

Communities? A Social Capital Perspective.

Healthcare (Basel).7(4),133.

Li, X.M., Liu, Y.J. (2000). Job Stressors and Burnout

among Staff Nurses. Chinese Journal of Nursing.

35(11),645-649.

Maqbali, M.A., Sinani, M.A., Al-Lenjawi, B. (2021).

Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep

disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19

pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 141,110343.

Marvaldi. M., Mallet. J., Dubertret, C., et al. (2021).

Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep

disorders among healthcare workers during the

COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-

analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 126,252-264.

Murat, M., Köse. S., Savaşer, S. (2020). Determination of

stress, depression and burnout levels of front-line

nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment

Health Nurs. 30(2),533-543.

Marroquín, B. (2011). Interpersonal emotion regulation as

a mechanism of social support in depression. Clinical

Psychology Review. 31(8), 1276-1290.

Pennebaker, J.W., 1997.Opening Up: The healing power

of emotional expression. New York, Guilford Press.

Parks, A.C., Schueller, S.M. 2004. The Wiley Blackwell

Handbook of Positive Psychological Interventions.

John Wiley & Sons.

Rimé, B. 2007. Interpersonal emotion regulation.

Handbook of Emotion Regulation. The Guilford Press.

London.

Sanliturk, D. (2021). Perceived and sources of

occupational stress in intensive care nurses during the

covid-19 pandemic. Intensive and Critical Care

Nursing. 67,103-107.

Salari, N., Khazaie, H., Hosseinian-Far, A., et al. (2020a).

The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression

within front-line healthcare workers caring for

COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-

regression. Hum Resour Health.18(1),100.

Salari, N., Khazaie, H., Hosseinian-Far, A., et al. (2020b).

The prevalence of sleep disturbances among

physicians and nurses facing the COVID-19 patients: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Global

Health.16(1),92.

Sahebi, A., Nejati, B., Moayedi, S., et al. (2021). The

prevalence of anxiety and depression among

healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic:

An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Progress in

Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological

Psychiatry. 107,110247.

Slepian, M.L, Moulton-Tetlock E (2018). Confiding

Secrets and Well-Being. Social Psychological and

Personality Science, 10(4),194855061876506.

Smith, A. 2002. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. New

York, Cambridge University Press.

Santini, Z.I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., et al. (2015).

The association between social relationships and

depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective

Disorders.175,53-65.

ICHIH 2022 - International Conference on Health Big Data and Intelligent Healthcare

42