Incorporating Privacy Requirements in Smart Communities for Older

Adults: A Research Vision

Fauzia Khan

a

and Ishaya Gambo

b

Institute of Computer Science, University of Tartu, Narva mnt 18 51009 Tartu, Estonia

Keywords:

Smart City, Privacy Requirements, e-Healthcare System, Requirements Engineering.

Abstract:

In recent years, socio-technical systems like smart city technology have received growing interest. Privacy re-

quirements in smart technologies hold significant importance, but it is difficult to elicit by traditional require-

ments elicitation techniques as several contextual factors are involved. Therefore, these techniques cannot be

effectively used to analyze privacy requirements. Our study aims to develop a framework that elicits privacy

requirements of older adults in smart communities and to improve the privacy awareness of individuals in

social groups. Our proposed framework is applied to a hypothetical scenario of an older adult using a smart

e-healthcare system to analyze privacy requirements and make users aware of whom they are sharing their

information with in social groups.

1 INTRODUCTION

In computing and socio-technical systems (e.g., smart

cities), privacy is a fundamental concern that neces-

sitates the amalgamation of technical and social per-

spectives in chatting the way forward for realizing

positive solutions. Most organizations and systems

are faced with privacy problems. For example, in the

healthcare domain, keeping patient’s medical records

and information private is an issue of concern.

Overall, privacy requirements engineering aims to

create systems that safeguard people and data while

taking into account changing risks, situations, and re-

quests in the context of use. The significant problem

is that already existing technologies, such as smart-

phones and wearable devices, have been successfully

used to define smart cities. Although providing su-

perior solutions in terms of ease of use and service

delivery, these technologies are also being utilized to

invade people’s privacy. These technologies exist in

a context, not in isolation. It could be in a social,

health, or educational environment where the tech-

nologies are used to socialize or augment socializa-

tion.

Until recently, smart city technology has received

growing interest, especially in the healthcare domain.

The most significant purpose of a smart city is to im-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9942-8709

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1289-9266

prove social or economic inconvenience and maxi-

mize social inclusion by using smart technologies and

data analysis (Harmon et al., 2015). However, its

complex nature has raised significant technical, politi-

cal, and socioeconomic challenges for designers, inte-

grators, and organizations involved in administrating

this technology (Ismagilova et al., 2020). In actuality,

smart cities are built to upgrade the quality of life for

ordinary citizens. For example, the residents of smart

homes can control their ventilation, lighting, heating,

cooling, and automatic door lock facilities. Also, they

can avail themselves of the benefits of security and

energy-saving.

In context, a smart city offers several facilities

like efficient transport, infrastructure, crime preven-

tion, traffic control, power, and water distribution (Pe-

ters et al., 2018). These services require capturing,

storing, and processing personally identifiable data,

which raises privacy issues. Ignoring privacy con-

cerns will lead to technology rejection and eventually

make unhappy users (Curumsing et al., 2019; Thielke

et al., 2012). Hence it is important to consider pri-

vacy requirements to make smart communities more

acceptable, specifically among older adults.

Privacy is both social and legal issue that holds

significant importance. In modern society, privacy

is an enabler of monitoring and searching informa-

tion (Thomas et al., 2014). The modern society in

this context is characterized by several individuals

having to share personal information with different

242

Khan, F. and Gambo, I.

Incorporating Privacy Requirements in Smart Communities for Older Adults: A Research Vision.

DOI: 10.5220/0011319100003266

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Software Technologies (ICSOFT 2022), pages 242-249

ISBN: 978-989-758-588-3; ISSN: 2184-2833

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

organizations, institutions, web services providers,

and online social networks (OSN). An example of

such an institution is the healthcare system that is

information-intensive, process- and service-oriented

(Gambo et al., 2011; Gambo et al., 2014; Gambo and

Soriyan, 2017).

On the one hand, eliciting privacy requirements,

for example, in older adults’ smart homes, can be

challenging from a requirement engineering (RE) per-

spective. In particular, designing standard techniques

for eliciting privacy requirements is considered not

to be straightforward and crystal clear because of the

following reasons. First, understanding the user per-

spectives about sharing data differs from each other,

e.g., social media updates are highly sensitive data for

some people while others are less concerned about

sharing it with others.

Secondly, privacy requirements are difficult to ex-

press due to the nature of people. In most cases,

people are unclear when expressing their privacy,

especially during the RE process. Therefore, it is

challenging for requirements engineers to recom-

mend standard techniques for eliciting privacy re-

quirements. Thirdly, in the context of smart cities,

many ubiquitous information technologies are in-

volved, e.g., clouds, wearable devices, sensors, and

smartphones. They all have contextual factors be-

cause standard techniques could not be effective.

On the other hand, people’s social behavior could

influence eliciting software privacy requirements.

People usually have different behavior and individual

privacy policies, but what happens when individuals

join groups like social groups, family groups, aca-

demic groups, etc. Usually, in groups, people are

not much concerned about what they have shared,

knowing who can see it. When people join a group,

they will have to follow the policies and rules of that

group. To understand this, we introduced the notion

of privacy dynamics to understand group dynamics,

especially on how people behaved in groups and tried

to use the individual privacy policy of people to learn

and improve the collective privacy awareness of the

group. For this purpose, we formulate two research

questions:

RQ1: How can we build an approach that cap-

tures learning new privacy dynamics within a speci-

fied system boundary and context?

RQ2: How can we use individual privacy to

learn and improve the group’s collective privacy

awareness?

The RQ1 and RQ2 are answered empirically in

Sections 3 and 4, respectively, but the contribution

is defined as a step-by-step method, not its applica-

tion. In answering RQ1, a framework is proposed to

capture privacy requirements. We considered a hy-

pothetical scenario of an older adult using the smart

e-healthcare domain and modeled its whole informa-

tion flow, analyzed the privacy problem, and cap-

tured the privacy requirements as reflected in Section

4. To answer RQ2, we proposed creating an infor-

mation database and sharing recommendation gener-

ator, which suggests to the user whether to share or

not share data with a specific member within a group

based on his actions performed in history. The pro-

posed framework is discussed in section 3 and illus-

trated via an example in section 4 by extending the

same scenario used for RQ1. Summing up, the fol-

lowing are the main contributions made in this paper:

• We propose a strategy for eliciting privacy re-

quirements from different contextual perspec-

tives, considering that smart cities have other ap-

plication domains that deal with the environment.

For this purpose, we developed a framework to

elicit privacy requirements for smart city domains

and learn how individuals’ privacy in a group

can affect the collective privacy awareness of the

group.

• We propose a framework to identify privacy

threats and dimensions to derive privacy require-

ments by modeling the information flow for the

system. We also identified other harms that pri-

vacy violations could produce.

• We propose a framework to provide privacy

awareness by understanding group dynamics and

user social behavior by suggesting sharing rec-

ommendation generator followed by information

gathering.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows. Sec-

tion 2 discusses some related work and its limitations.

Section 3 presents our proposed approach. Section 4

illustrates an example of a case study to describe how

our approach can be used. Section 5 states the con-

clusion and future work.

2 RELATED WORK

The literature has proved that privacy issues have a

long history dated far back to 1890. In particular, it

is ”the right to be left alone” (Brandeis and Warren,

1890) and ”the right to select what personal infor-

mation about me is known to what people” (Westin,

1968). Also, in the modern world of mobile, ubiqui-

tous, adaptive, service-oriented, and human-centered

Incorporating Privacy Requirements in Smart Communities for Older Adults: A Research Vision

243

systems, the literature on privacy concern has pro-

vided to a great extent some levels of satisfaction for

the business and social needs of users and enterprises.

Thus, Omoronyia et al. (2013) observed that these

applications enable users to form localized, short and

long lived groups or communities to achieve their

common objectives. The behavioral nature of these

applications will involve the collection, dissemina-

tion, and even disclosure of sensitive information,

which threatens users’ privacy when exposed in an

unregulated manner (Langheinrich, 2002; Omoronyia

et al., 2013). This is the reason behind the failure

of systems that cannot provide satisfactory privacy

awareness requirements.

Further, the concept of adaptive privacy as a sys-

tem’s ability to preserve privacy in the presence of

context changes was introduced in (Schaub et al.,

2012) to cater for group dynamics. These changes

could be due to several expectations from users in a

group, which changes all the time, and the predomi-

nant behavior of users that enforces the change. How-

ever, the notion of a group is quite fundamental to how

privacy is being managed. For example, groups have

some knowledge or wisdom that can be exploited. So,

trying to understand the group property of privacy is

essential.

Calikli et al. (2016) presented a privacy dynamics

architecture inspired by social identity theory. The re-

search was based on a formal model with the concepts

of group membership information, represented as so-

cial identity maps, and privacy norms, represented as

a set of conflicts. Also, the research used the Induc-

tive Logic Programming (ILP) to learn a user’s pri-

vacy norms through examples of their sharing behav-

ior (Calikli et al., 2016). However, Calikli et al.’s

(2016) work was based on assumptions, and the ILP

was subjected to learning user’s privacy norms as real

users sharing behavior were not used.

Additionally, few studies are available on elicit-

ing smart cities’ privacy requirements. For example,

(Miller et al., 2012) used interviews and question-

naires but found it challenging to capture the actual

privacy concern. Also, (Taveter et al., 2019) used

the motivational goal modeling approach to capture

stakeholders goals, including some privacy concern.

Their specific focus was on the healthcare domain that

was based on two case studies related to the e-health

sector in Estonia and Australia. Unfortunately, mul-

tidisciplinary skill sets are required to use it for their

proposed approach.

Moreover, Taveter et al. (2019) had blended a

top-down approach with a bottom-up approach which

could create a problem regarding viewpoint decision,

especially on determining which viewpoint is right or

wrong. A 2x2 framework is proposed to gather pri-

vacy concerns for smart cities in (Van Zoonen, 2016).

One dimension shows people’s more sensitive data

than others, whereas the other dimension shows peo-

ple’s privacy concerns regarding the purpose of data

being collected.

The author in (Van Zoonen, 2016) showed the ap-

plicability of the proposed framework and gave clear

directions for doing empirical research about privacy

concern in smart cities. (McNeill et al., 2017) focused

on the importance of privacy concerns of older adults

in the healthcare domain. They used thematic analy-

sis to identify six reasons older adults need privacy

and concluded that the designer should incorporate

privacy goals at the beginning of the designing phase

but did not discuss the design solution with their par-

ticipants whether the solutions are plausible or not.

Worthy of mention is the work by (Mart

´

ınez-

Ballest

´

e et al., 2013) on smart cities that defined five

dimensions of the privacy model. Still, traditional

techniques for eliciting privacy requirements are not

effective for the following reasons.

1. There is limited knowledge on capturing privacy

requirements and incorporating them in the soft-

ware design as every domain in smart cities has

dynamic characteristics, user involvement, het-

erogeneity, and scalability. Therefore, it is neces-

sary to be aware of privacy threats and concerns

when designing a new system or extending the

current system.

2. User behavior varies based on the scenario. For

example, a user may want to share his mobile

screen with his friend while sitting in a cafe. Still,

he will not be comfortable sharing it with the pas-

senger sitting next to him in a bus, or he may share

his photos with friends but with no teachers in his

university social group.

To fill this gap, we proposed a framework that could

be effective for any smart city domain to elicit privacy

threats and concerns by modeling its information flow

and making the user aware by providing suggestions

on whether to share information with a particular in-

dividual in a group or not.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

We employed the qualitative and deductive ap-

proaches in SE (Runeson et al., 2012) to address the

research questions. These approaches are descrip-

tive and explanatory, using a hypothetical older adult

smart homes scenario. To address RQ1, we formu-

lated a framework called Privacy Requirements and

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

244

Figure 1: Framework for Privacy Requirements.

Awareness (PRA) in a few steps, as shown in Figure 1.

As Figure 1 reflects, our framework consists of

four phases: (i) Smart City Domains, which provides

smart solutions across all sectors, so we categorized

smart city sectors in smart mobility, buildings, envi-

ronment, governance, economy, health care defines

the different domain of the smart city. (ii) Modelling

Information Flow. In particular, as information flows

between different users and have different flow path

with a different purpose, we modeled the information

flow to identify roles, relations, and flow of informa-

tion between actors. (iii) Analyzing Privacy Problem.

This phase identifies privacy threats and concerns in

the flow of information. (iv) User Privacy Require-

ments - To capture and categorize user privacy needs.

3.1 Smart City Domains

Smart city domains refer to different systems like

smart transport systems, smart health care systems,

smart buildings, etc. ”Here, we noted that ascertain-

ing privacy solutions for smart cities is a difficult and

error-prone task because their heterogeneity and com-

plexity have limited the traditional requirements engi-

neering methodologies to elicit or capture stakehold-

ers’ privacy expectations”. As observed in (Thomas

et al., 2014), using traditional means to elicit pri-

vacy requirements is hard and incredibly impractical

for mobile, ubiquitous, service-oriented, and human-

centered systems. Remarkably, smart city domains

are highly context-dependent, and privacy require-

ments change from domain to domain and from an

end-user perspective. For example, in the healthcare

domain, the goal of smart health is to educate pa-

tients about their medical status and keep them health

aware. The kind of data in this domain includes pa-

tient health data and survey data. We focus more

on the older adults’ privacy requirements for this re-

search. Other smart city domains are Smart Mobility,

Smart Utilities, Smart Buildings, Smart Environment,

Smart Traffic Systems, Smart Governance, and Smart

Economy.

3.2 Information Flow Model

In this phase, the flow of information in the smart

city domain must be identified, and how it is dissem-

inated to other users should be established. For that,

we identified four facets:

1. Information Facet: The information facet entails

categorizing the type of information, the purpose

of use, and the subscriber who can receive the in-

formation. This is to model what type of informa-

tion is involved and to whom it is disseminated to

other users, and the purpose of using the informa-

tion.

(a) Type of Information: Type of Information:

The focus is on knowing whether the infor-

mation is personal or confidential. For that,

the information can be a sensitive information,

which can be user-related information, such as

date of birth, medical records, mobile num-

ber, civic data, age, etc. This information can-

not be made public without the consent of the

owner. On the other hand, the information can

be insensitive information, user-related infor-

mation, such as name, gender, or other infor-

mation that can be made public with its owner’s

consent.

(b) Purpose: The focus is to identify for what

purpose data is being collected and how these

data pieces are used. As described in (Bha-

tia and Breaux, 2017), the purpose of data can

be for: a) Service, which includes any pur-

pose for which a company uses users’ data to

improve their services, e.g., search results, ad-

vertisements, or location-based services.b) Le-

gal purpose, which includes any legal purpose

regarding following the court notifications or

any other litigation. c) Communication pur-

pose that includes any purpose regarding com-

munication with users to address different pur-

poses, e.g., products, product updates, and ser-

vices, etc., d) Protection purpose that includes

any purpose related to fraud, data manipulation,

protection, and misuse e.g., to detect fraud in fi-

nancial services like credit cards. e) Merger

purpose that includes any purpose regarding

mergers or transferring control and property to

others. f) Vague purpose that includes any pur-

pose whose reason and consequences are un-

clear or any purpose which is not covered by

other mentioned purposes above.

Incorporating Privacy Requirements in Smart Communities for Older Adults: A Research Vision

245

(c) Subscriber: The emphasis is on whom infor-

mation need to be shared with, and to ascertain:

i. Whether others could see or receive personal

information or activities about users, thereby

informing users who can see their informa-

tion.

ii. What is the medium used for data collection?

Is data collected manually by end-users or by

computer automation?

2. Actor Facet: Identifying users with whom the

system interacts. For example, in the context of

the health care system, patients and doctors are

actors.

3. Role and Responsibility Facet: Identifying the

roles and responsibilities of actors (sender, re-

ceiver, and subject) holds significant importance

to ensure privacy. For example, in the taxi sys-

tem, the details of pickup and destination location

of a passenger may be required by the driver. So

both the driver and passenger with their relation-

ship and responsibility should be defined clearly.

4. Data Flow Facet: It is important to know how

data flow between actors to examine the privacy

requirements. The following question can be used

to elicit privacy factors.

(a) Is there any system and third party involved

who are recipients of information?–Determines

the information flow to a third party who can

exploit data.

(b) To identify the relationship between subjects

and system and third party?

(c) How subject feel in relation to software which

they are using i.e. trust relationship.

5. Owner, Consent and Permission: To identify

that who can control the use of sensitive infor-

mation? Owns: An actor who is legal owner of

data, Permission: An actor has full control to use

the information which he owns. Consent: is a le-

gal agreement between subject and another actor,

who can use the information with specific purpose

of use shown in agreement.

3.3 Privacy Problem Analysis

There are eight types of privacy according to study

(Friedewald et al., 2013) which include: Privacy

by person (genetic code, bio metric codes) Loca-

tion (traces, spatial-temporal data), Media (audio, im-

age, video), Behavior, and action (hobbies, purchases,

habits), Social life (interactions, contacts) State of

mind and body (thought, health opinion) association

(group privacy), communication (email, phones).

For analysis purposes of privacy requirements and

for sake of simplicity, first a generic architecture for

the flow of information between sender and receivers

was considered so that we can identify different pa-

rameters involved in information flow to elicit privacy

requirements. Usually, the information flows in three

steps as follows (Doyle, 2011): Firstly, the sender

sends information to a service provider and service

provider stores it. Secondly, receivers requests the

data from a service provider. At last, Upon request,

the service provider sends information to receiver. In

above mentioned information flow, following param-

eters contributed in order to elicit privacy require-

ments:

1. Risk Dimension: A potential incident which can

cause negative impact on overall software e.g

threats and vulnerability which can exploit user

information.

2. Vulnerability: A weakness of a system which can

be exploited by a threat actor i.e to perform unau-

thorized actions.

3. Privacy Violation: It occurs when any informa-

tion flow causes harm to user. Harmful activi-

ties could occur in Loss of (Reputation, Freedom,

Finance, Anonymity, Relationship, Emotional

Harm, Embarrassment, Discrimination, Black-

mailing, Criminal Offence etc).

4. Privacy Determinants: To Identify component

which affects privacy in information flow.

5. Privacy Threats: To map the path of information

flow in software from where users can suffer harm

and identify the gaps in the requirement model

of current software. According to (Solove, 2005)

there are four basic groups of infraction flow

which can cause harmful activities.1)Information

collection, 2)information processing, 3)Informa-

tion dissemination, 4)Invasion. Few examples of

threats could be related to Surveillance, Interroga-

tion, Aggregation, Identification, Insecurity, Prox-

imal access, Secondary use, Breach of Trust, Mis-

information, Power Imbalance, Interference, and

Cross Contextual Information.

6. Privacy Goal: To counter threats in order to make

information protected and secured.

7. Privacy Constraint: To introduce restriction in

design of software to achieve privacy goals. It

is achieved by introducing privacy policy (actions

of actors which are allowed or prohibited to do)

and privacy mechanism (technique to implement

to achieve privacy goals).

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

246

3.4 Privacy Requirements

To address privacy threats and violations by pro-

viding feedback and control facilities so that user

can have better control over the information flow

and thus improve the privacy requirements of

the software.According to (Dritsas et al., 2006;

Gharib et al., 2021), privacy requirements are fur-

ther refined into eight concepts:

(a) Confidentiality: It means to incorporate all

necessary actions to keep user information in

accessible in case of any threat.

(b) Authentication: It means to incorporate mech-

anisms to verify who is accessing subject’s in-

formation.

(c) Authorization: It means to incorporate mech-

anism to verify whether actors have permission

to access the subject’s information with their

credentials.

(d) Notice: To send data notice to subject when its

information has been collected. Also a viola-

tion notice should be send in case the subject

does not permits to do so.

(e) Anonymity: To keep the activities without dis-

closing the user identity of subject i.e. to re-

move identifiers like name , address, etc.

(f) Unlinkable: To make subjects unable to asso-

ciate information to its subject or to determine

whether the same user caused certain specific

operations in the system.

(g) Unobservant: It requires that subjects cannot

determine whether an activity or operation is

being performed.

(h) Accountability: It requires that company who

collect or use personal data take responsibility

for its protection and appropriate use.

To address RQ2, we divide our proposed approach

in two parts:

1. Information Database: In this step, we aim to

develop a repository that contains user names,

names of other group members (friends, col-

leagues, family) sharing objects like (images, sta-

tus, reports) and user sharing history and conflict.

For example user shared his photos with friends

but not with his class teacher in classroom group.

2. Recommendation Generation: After gathering

the whole information a recommendation genera-

tor will maps conflicts by analysing history of user

and will send sharing recommendation to user ev-

ery time when user is going to share something

on group. Figure 2 shows block diagram for pro-

posed approach.

Figure 2: Group Dynamics to Make Privacy Awareness.

4 ILLUSTRATING THE

APPLICABILITY OF THE

PROPOSED FRAMEWORK

In this section, we illustrated a hypothetical scenario

of independent old adult in healthcare domain. Due

to the age factor, older adults become weak men-

tally and physically, thus dependent on others. How-

ever, they want to live in their homes independently.

For this purpose, they used smart technology regard-

ing health domains like a smartwatch, bed, auto-

generated alarms, etc. They can be monitored con-

tinuously by health experts without face-to-face in-

teraction. In a smart health care system, health ex-

perts will take appropriate measures if older people

show abnormal signs in their activities or behavior.

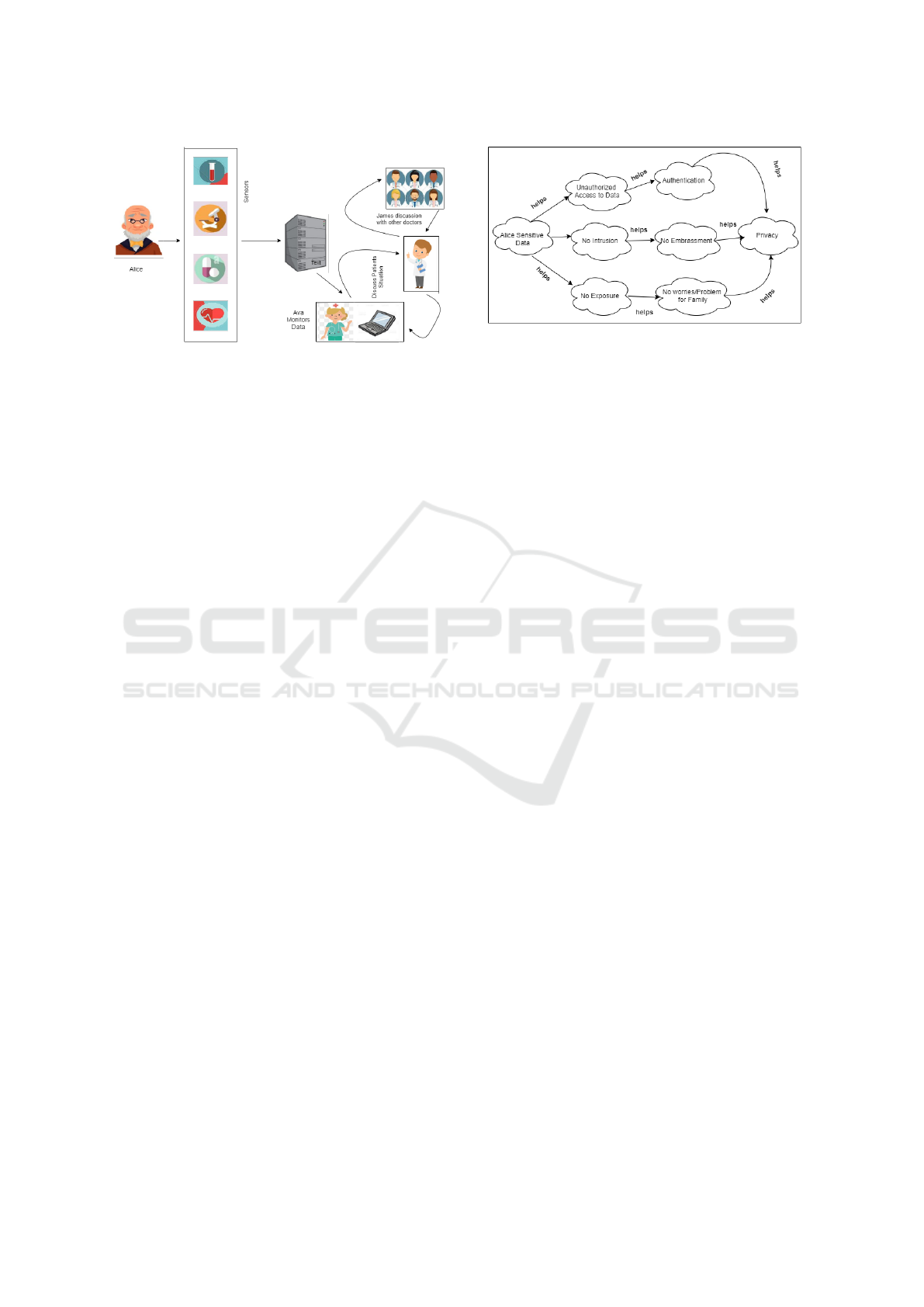

We describe a hypothetical scenario of Alice, who

is 65 years old and suffers from pains in the knees

and wrist and a recent heart attack which his family

does not know. Alice relies on different body sensors,

which collect information by monitoring his motion,

Location, blood pressure, glucose level, ECG, and

pain levels. A nearby health center has a nurse, ”Ava”

who can also monitor all information using the system

shown in Figure 3. Ava can call the required doctor

if Alice’s condition deteriorates. He shared his auto-

generated medical reports with a group consisting of

doctors and family, but the last time he got a cardiac

attack, he shared the reports with doctors and not with

family. Also, Alice is concerned about his privacy and

wants to know which information is shared with oth-

ers and its purpose.

The following describes how the privacy require-

ments present in the hypothetical scenario can be

specified using our proposed framework.

Domain of Smart City: Smart Heath Care System.

Information Facet:Personal Information (Name,

age, profession, telephone, address and affiliation)

and Personal health data: Alice’s cardiology data.

Actor Facet: Alice, Ava, James

Relationship Facet: (Alice relationship with Ava:

Alice - Nurse), (Ava relationship with system: Ava

- system), (Alice’s relationship with James: Alice –

Incorporating Privacy Requirements in Smart Communities for Older Adults: A Research Vision

247

Figure 3: Alice Data Monitoring using Smart Technologies.

James), (James relationship with the Institute: James

- Institution)

Trust Relationship: (Alice trust Ava that they will

not reveal his information to family), (Alice trust

James that they will not reveal his information to fam-

ily), (Alice trusts the James that he will share his in-

formation with other colleagues/doctors only when

needed), (James trusts his colleagues by allowing the

sharing of Alice health personal data).

Data Flow Facet: (Alice information flows to sys-

tem), (System sends notification to Ava), (Ava sends

information to doctor).

Owner, Consent and Permission: Alice is owner,

Granting permission to Ava to float his data to James

to doctor and if his condition deteriorates and may re-

quired any major procedure then Ava can inform his

family.

Risk Dimension: Alice information is disclosed.

Vulnerability: Someone else access or shared Alice

data.

Privacy Violation: (Intrusion may cause embarrass-

ment), (Disclosing Alice personal data may cause

worries problem at home).

Privacy Determinants: (Data leakage threats),

(Unauthorized access to system), (Human Mistakes)

Privacy Threats: Disclosing Alice information

caused threats i.e. Exclusion and Interference which

cause harms like Embarrassment

Privacy Goal: To make Alice data Confidential.

Privacy Constraint: (Alice should share data tem-

porarily), (James and Ava may not share the data

without permission of Alice).

Information Database: (Alice is user and group

members are Alice, James, Ava and family members

whereas reports are sharing object), (Reports not shar-

ing with family last time is conflict and history).

Alice’s privacy depends on Ava, James, and System.

If there is no undue access to his sensitive data, he

will not be embarrassed, nor will his family be wor-

ried. Figure 4 shows privacy is insured if there is no

unauthorized access to his confidential data.

Figure 4: Scenario Modelling.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper introduced a systematic approach to anal-

yse privacy requirements in smart cities from a re-

quirements engineering vie software flow by which

software analysts can take advantage. Also, we pro-

vided a framework to improve individual privacy in

social groups. We considered a hypothetical scenario

of older adults in the health care system for eliciting

privacy requirements. For now, our framework is yet

to be evaluated with real-life data, as we plan to con-

sider that for future work. Also, we aim to demon-

strate our proposed framework on the E-health sector

and get it evaluated by domain experts. Furthermore,

we intend to incorporate older adults’ emotional con-

cerns into the current proposed approach by leverag-

ing psychological theories and suggest a strategy for

managing conflicts in emotional goals based on our

earlier framework in (Gambo and Taveter, 2021) and

(Gambo and Taveter, 2022).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Institute of Com-

puter Science at the University of Tartu, Estonia for

the support in executing the research. The research

has received funding from the European Social Fund

via the IT Academy programme awarded to the sec-

ond author.

REFERENCES

Bhatia, J. and Breaux, T. D. (2017). A data purpose case

study of privacy policies. In 2017 IEEE 25th Inter-

national Requirements Engineering Conference (RE),

pages 394–399. IEEE.

Brandeis, L. and Warren, S. (1890). The right to privacy.

Harvard law review, 4(5):193–220.

ICSOFT 2022 - 17th International Conference on Software Technologies

248

Calikli, G., Law, M., Bandara, A. K., Russo, A., Dickens,

L., Price, B. A., Stuart, A., Levine, M., and Nuseibeh,

B. (2016). Privacy dynamics: Learning privacy norms

for social software. In 2016 IEEE/ACM 11th Interna-

tional Symposium on Software Engineering for Adap-

tive and Self-Managing Systems (SEAMS), pages 47–

56. IEEE.

Curumsing, M. K., Fernando, N., Abdelrazek, M., Vasa, R.,

Mouzakis, K., and Grundy, J. (2019). Understand-

ing the impact of emotions on software: A case study

in requirements gathering and evaluation. Journal of

Systems and Software, 147:215–229.

Doyle, T. (2011). Helen nissenbaum, privacy in context:

technology, policy, and the integrity of social life.

Dritsas, S., Gymnopoulos, L., Karyda, M., Balopoulos, T.,

Kokolakis, S., Lambrinoudakis, C., and Katsikas, S.

(2006). A knowledge-based approach to security re-

quirements for e-health applications. Electronic Jour-

nal for E-Commerce Tools and Applications, pages 1–

24.

Friedewald, M., Finn, R. L., Wright, D., Gutwirth, S.,

Lenes, R., Hart, P., and Poullet, Y. (2013). Seven

types of privacy. European Data Protection: Coming

of Age, pages 3–32.

Gambo, I., Oluwagbemi, O., and Achimugu, P. (2011).

Lack of interoperable health information systems in

developing countries: an impact analysis. Journal of

Health Informatics in Developing Countries, 5(1).

Gambo, I., Soriyan, A., and Ikono, R. (2014). Framework

for enhancing requirements engineering processes: a

conceptual view of health information system. Inter-

national Journal of Computer Applications, 93(2).

Gambo, I. and Taveter, K. (2021). A pragmatic view on

resolving conflicts in goal-oriented requirements engi-

neering for socio-technical systems. In Proceedings of

the 16th International Conference on Software Tech-

nologies, ICSOFT 2021, pages 333–341.

Gambo, I. and Taveter, K. (2022). Stakeholder-Centric

Clustering Methods for Conflict Resolution in the Re-

quirements Engineering Process, volume 1556 CCIS

of Communications in Computer and Information Sci-

ence.

Gambo, I. P. and Soriyan, A. H. (2017). Ict implementa-

tion in the nigerian healthcare system. IT Professional,

19(2):12–15.

Gharib, M., Giorgini, P., and Mylopoulos, J. (2021). Copri

v. 2—a core ontology for privacy requirements. Data

& Knowledge Engineering, 133:101888.

Harmon, R. R., Castro-Leon, E. G., and Bhide, S. (2015).

Smart cities and the internet of things. In 2015 Port-

land International Conference on Management of En-

gineering and Technology (PICMET), pages 485–494.

IEEE.

Ismagilova, E., Hughes, L., Rana, N. P., and Dwivedi, Y. K.

(2020). Security, privacy and risks within smart cities:

Literature review and development of a smart city in-

teraction framework. Information Systems Frontiers,

pages 1–22.

Langheinrich, M. (2002). A privacy awareness system for

ubiquitous computing environments. In international

conference on Ubiquitous Computing, pages 237–245.

Springer.

Mart

´

ınez-Ballest

´

e, A., P

´

erez-Mart

´

ınez, P. A., and Solanas,

A. (2013). The pursuit of citizens’ privacy: a privacy-

aware smart city is possible. IEEE Communications

Magazine, 51(6):136–141.

McNeill, A., Briggs, P., Pywell, J., and Coventry, L. (2017).

Functional privacy concerns of older adults about per-

vasive health-monitoring systems. In Proceedings of

the 10th international conference on pervasive tech-

nologies related to assistive environments, pages 96–

102.

Miller, T., Pedell, S., Sterling, L., Vetere, F., and Howard,

S. (2012). Understanding socially oriented roles and

goals through motivational modelling. Journal of Sys-

tems and Software, 85(9):2160–2170.

Omoronyia, I., Cavallaro, L., Salehie, M., Pasquale, L., and

Nuseibeh, B. (2013). Engineering adaptive privacy:

on the role of privacy awareness requirements. In

2013 35th International Conference on Software En-

gineering (ICSE), pages 632–641. IEEE.

Peters, F., Hanvey, S., Veluru, S., Mady, A. E.-d.,

Boubekeur, M., and Nuseibeh, B. (2018). Generat-

ing privacy zones in smart cities. In 2018 IEEE Inter-

national Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), pages 1–8.

IEEE.

Runeson, P., H

¨

ost, M., Rainer, A., and Regnell, B.

(2012). Case study research in software engineering-

guidelines and examples wiley.

Schaub, F., K

¨

onings, B., Weber, M., and Kargl, F. (2012).

Towards context adaptive privacy decisions in ubiq-

uitous computing. In 2012 IEEE International Con-

ference on Pervasive Computing and Communications

Workshops, pages 407–410. IEEE.

Solove, D. J. (2005). A taxonomy of privacy. U. Pa. L. Rev.,

154:477.

Taveter, K., Sterling, L., Pedell, S., Burrows, R., and

Taveter, E. M. (2019). A method for eliciting and

representing emotional requirements: Two case stud-

ies in e-healthcare. In 2019 IEEE 27th Interna-

tional Requirements Engineering Conference Work-

shops (REW), pages 100–105.

Thielke, S., Harniss, M., Thompson, H., Patel, S., Demiris,

G., and Johnson, K. (2012). Maslow’s hierarchy

of human needs and the adoption of health-related

technologies for older adults. Ageing international,

37(4):470–488.

Thomas, K., Bandara, A. K., Price, B. A., and Nuseibeh,

B. (2014). Distilling privacy requirements for mobile

applications. In Proceedings of the 36th international

conference on software engineering, pages 871–882.

Van Zoonen, L. (2016). Privacy concerns in smart cities.

Government Information Quarterly, 33(3):472–480.

Westin, A. F. (1968). Privacy and freedom. Washington and

Lee Law Review, 25(1):166.

Incorporating Privacy Requirements in Smart Communities for Older Adults: A Research Vision

249