CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT IN AN

ELECTRONIC ECONOMY

Anthony W Marsh and Anthony S Atkins

Faculty of Computing, Engineering and Technology, Staffordshire University, Octagon, Beaconside, Stafford, UK

Keywords: Customer Relationship Management (CRM), Strategic IT, Data Warehousing, Data Integration, Enterprise

Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Service, Marketing, Sales and Mobile Technology.

Abstract: In the last few years Customer Relationship Management (CRM) has been the subject of considerable

interest in the business world. This has sometimes resulted in exaggerated claims about the benefits on

offer to organisations. This paper provides an insight to the underlying concepts of CRM, the technological

changes, and the impact to the organisational structure, its processes and the three main business divisions

relied upon to deliver customer intimacy – specifically, Customer Service, Marketing and Sales. The paper

highlights examples where CRM initiatives have been implemented for cost savings, profitability growth

and a competitive advantage. The paper also outlines how many organisations are seeking to realign and

empower the lower ranks of the business to nurture and harvest one-to-one customer relationships. The

paper indicates that organisations need to review business operations in order to meet the challenges of

delivering customer focus and outlines a framework as a planning tool to utilise CRM technology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Undoubtedly, Information Technology (IT) is

revolutionising the many areas of business.

Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

attempts to make appropriate use of technological

capability to meet ever-increasing demands placed

on organisations through fierce competition,

escalating costs and growing consumer expectations.

It is therefore no wonder that CRM has rapidly

become a popular ‘buzzword’ in many organisations

around the world in an effort to counteract these

concerns. Contrary to popular belief, CRM does not

exist as a separate entity or division. It is a sell-side

collection of strategies, processes and tasks that

allow an organisation to form mutually beneficial

one-to-one relationships with each of its customers.

The CRM culture and attitude to business means that

organisations can expect improved levels of

efficiency and effectiveness as a result of automating

business processes and tasks for customer-focus.

This in turn can lead to significant operational cost

reductions and allow for an improved understanding

of customers for interpretation. This accumulates

new marketing and selling opportunities that can

produce significant improvements in financial

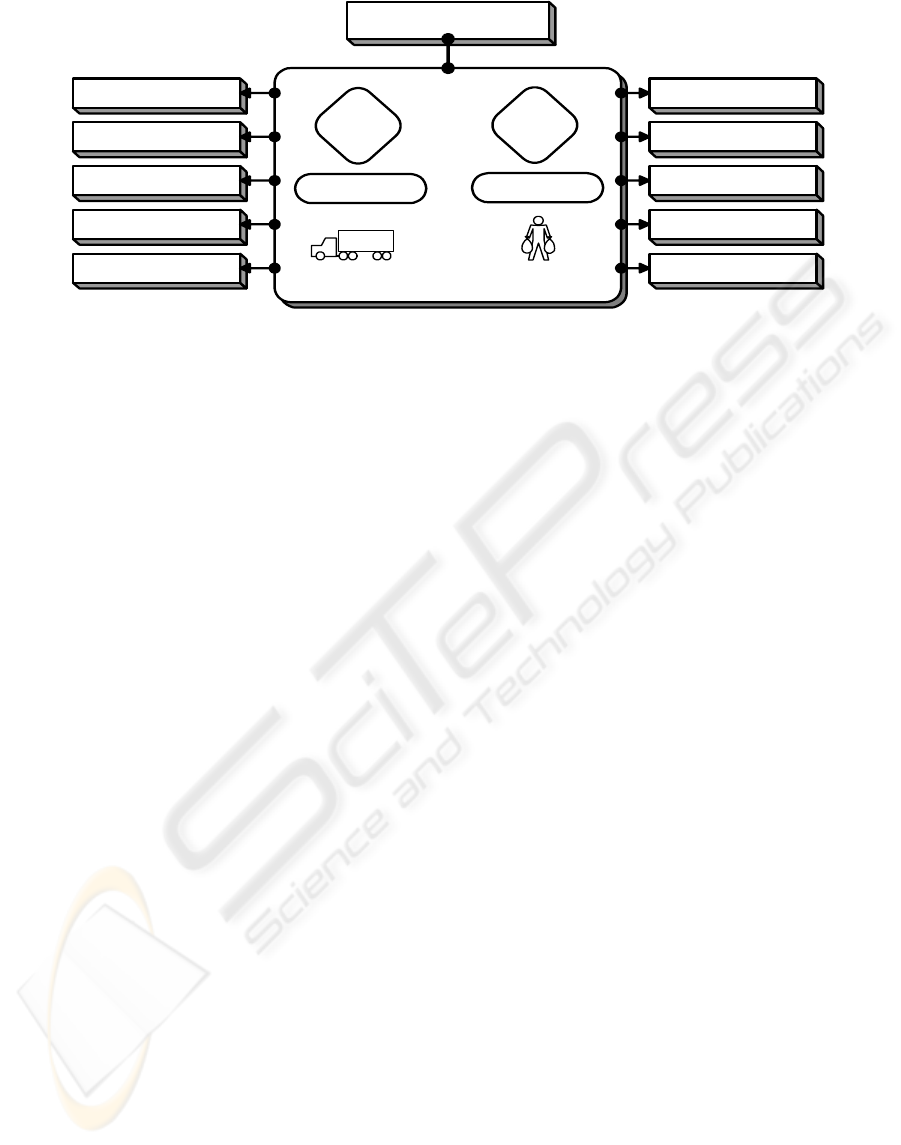

profitability. Figure 1 outlines the two facets of an

organisation and clarifies CRM’s environment.

Over the past few decades, organisations have

concentrated on product innovation to win over

customers. The rapid globalisation of the Internet

and its associated technologies has meant it is far

easier for organisations to establish their position in

an increasingly populated marketplace.

Consequently, this has provided the consumer with

an escalating ease at which they are able to buy their

products or services. Alexander and Turner [2001]

point out that the Internet discourages brand loyalty

and encourages “serial switching” since product

information such as pricing discounts and

specifications can be communicated far more easily.

Serial switchers are customers who are not loyal to

an organisation or its products; moreover, they are

more concerned with the price and aesthetics of each

product they buy rather than brand virtues or where

they buy it. Effectively, these customers return very

little profit to the business bearing in mind the costs

associated with their acquisition and support.

Another difficulty to overcome is that of shorter

product lifecycles [Findlay 2000]. Organisations

now have to invest heavily in customer-focused

research and development to remain competitive.

103

S. Atkins A. and Marsh A. (2004).

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT IN AN ELECTRONIC ECONOMY.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on E-Business and Telecommunication Networks, pages 103-110

DOI: 10.5220/0001386401030110

Copyright

c

SciTePress

In the motor industry, model lifetimes have been

reduced significantly. This has resulted in models

having more ‘facelifts’ to freshen their market

appeal. More often than not, these have been the

outcome of both customer feedback and ‘Kaizen’

continuous improvement programmes.

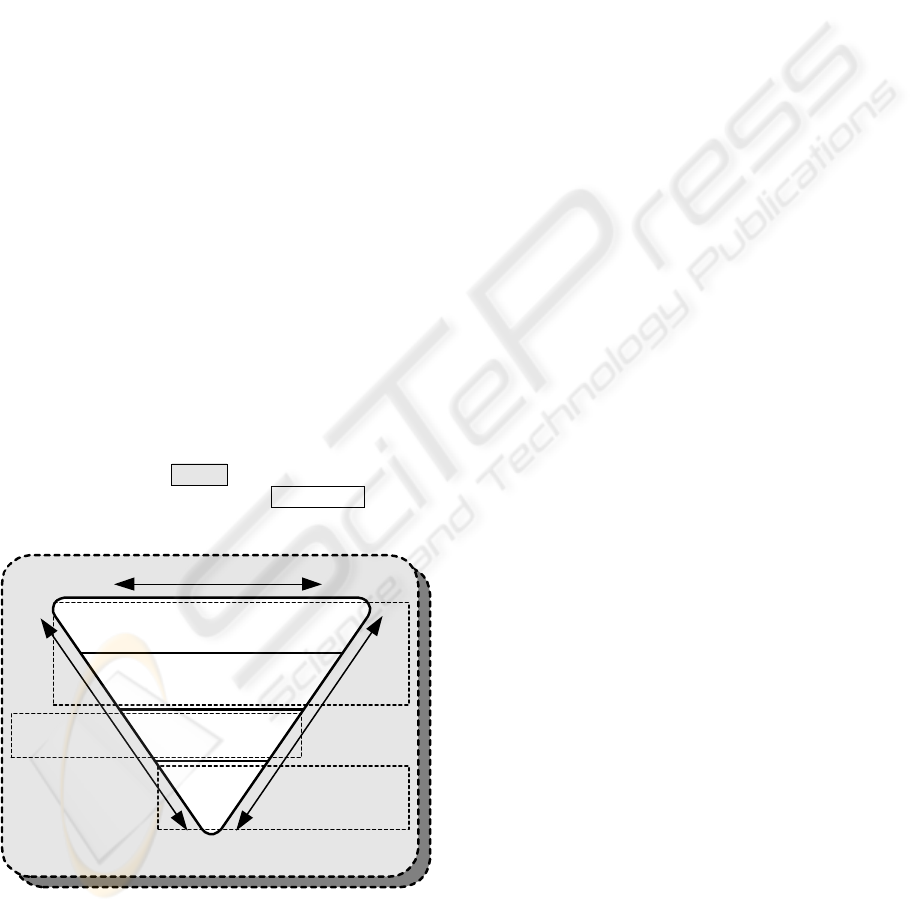

The underlying component of the CRM philosophy

is customer centricity. Customer centricity is about

ensuring all aspects of the organisation are geared

towards creating, fulfilling and sustaining positive,

intimate relationships with customers. Vellmure

[2003] decomposes customer centricity into five

areas indicated in Figure 2. Organisations that are

customer centric are able to utilise the two main

mechanisms of CRM – customer retention and

customer personalisation. Research outlined by

Payne [2000] has shown that an organisation can

increase profits between 20 and 125 per cent by

retaining just five per cent of its most profitable

customers. Furthermore, it can also cost an

organisation as much as four to seven times to obtain

a new customer than it does to retain one [Findlay

2000]. Clearly, customer retention makes economic

sense. A classic example of modern times is the

mobile telecommunications industry. At the end of

a 12-month contract an operator will call to offer the

customer a new contract at a discounted price as an

incentive. This is because the organisation will not

have the costs associated with a ‘new customer’ –

like setting up new administrative accounts or the

cost of promotions and discounts for new customer

acquisition. Nevertheless, not all customers are as

profitable as each other therefore it is essential that

the organisation is able to evaluate each customer

for their current and future intrinsic worth in order to

personalise the way in which it interacts with them.

Analysing past purchase history is an example of

how to categorise the level of preferential treatment

a customer may justify; although in reality it will be

a number of more complex and simultaneous factors

that will determine a customer’s real value over

time. Organisations are then able to offer a mix of

the right products along with an appropriate level of

service to its customer base more accurately, and

most importantly, more profitably. Even so, the

success of this will depend on the quality of its

customer data, the capability of its data analytics and

the abilities of its people.

2 CRM TECHNOLOGIES

Despite the advances of technology, CRM will

always remain a business philosophy. Many of its

underlying concepts have actually been around for

many years; it is only due to the evolution in

computer processing speed, storage capacity and

database technology that some of the ideas proposed

years ago have been made more accessible to all

today. Furthermore, the reduced cost of technology

has enabled smaller organisations to compete more

fairly with their larger counterparts; resulting in

more competitive markets. Nowadays, many

organisations have invested in large data

warehouses. One of the drivers of which has been

the trend to replace legacy computer systems that are

often characterised as being a poor source of

supportive information to base tactical and strategic

business decisions. However, they are critical for

CRM since large quantities of customer data will be

restructured, ‘mined’ and analysed for the extraction

of customer retention tactics, personalisation

techniques and recognising new marketing and

selling opportunities. Even though data

Corporate Strategy & Objectives

Supply Chain Management

(SCM)

Customer Relationship

Management (CRM )

$$

CustomersSuppliers

Buy-side

Strategy

Sell-side

Strategy

Distribution Planning

Product Configurations

Sales and Demand Forecasting

Order Processing & E-

Procurement

Warehouse Management/

Inventory Handling Systems

Data Warehousing/Data Mining/

Business Intelligence

E-Commerce

Sales

Marketing

Customer Service

Fi

g

ure 1: The two facets of an or

g

anisation

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

104

warehouses are notorious for being expensive and

time-consuming to maintain, Manning [2000]

suggests that they are a “long-term delivery

mechanism for ongoing management needs” and as

such, represent good value for money in the strategic

sense.

Inherently, the accuracy, consistency and

completeness of the organisation’s customer data

will form a central role in CRM. In a typical CRM

system, data and information is constantly

exchanged across the organisation therefore a

compatible or integrated systems platform is

essential – for example, customer interaction can

take place over many channels (e.g. post, telephone

or email) therefore it is easy to see how problems

with data integrity is undesirably achieved. Findlay

[2000] likens CRM data flows as “fluid” since the

transfer and update of data across the business is

continuous all of the time. Unsurprisingly,

integration is one of the major challenges CRM

projects have to overcome and as a result; data and

systems integration proves one of the most costly

aspects in CRM budgets. Poorly integrated systems

can lead to duplicate data, mismatched information

and inaccurate reporting. Data maintenance

attempts to prevent this but is both time-consuming

and expensive. Khanna [2000] identified that one of

the main reasons for poorly integrated systems is

that organisations traditionally adopted ‘best of

breed’ applications, i.e. separate applications to

support specialist areas of the business (e.g. finance

and logistics). Nevertheless, integration is becoming

easier thanks to the introduction of a number of

technologies such as XML (eXtended Mark-up

Language - a universal standard for electronic data

interchange) and legacy extension toolkits that are

designed to integrate old data with new IT systems.

Since CRM is data intensive, Delahoz [2000]

suggests the benefits of legacy integration tools

should not be underestimated as organisations can

benefit from rapid implementations at a substantially

reduced cost. Elsewhere, there are a number of large

organisations using their Enterprise Resource

Planning (ERP) systems (e.g. SAP and Peoplesoft)

for their CRM needs. Since ERP modules share and

interchange a common set of data transparently,

ERP organisations are said to have the upper hand of

CRM. Unfortunately, recent research has shown

that ERP software can cost between €3,000 and

€87,000 per seat depending on how it is

implemented [Saran 2003]. On an equal scale,

organisations also face radical process re-design.

CRM is generally conceived to be one of the main

drivers of mobile technology. This is supported by

Kaakani (2001) who identified that business

transactions were becoming increasingly automated

yet customer-facing processes were still mainly

manual based. Up until the arrival of CRM, Fickel

(2001) observed that the main obstacle for the

acceptance of mobile databases had been a shortage

of business-driven application demand. The rise of

mobile technology is now accepted as a normal part

of life mainly due to smaller powerful devices,

decreasing bandwidth costs and platform

standardisation. The relevance to CRM is that the

Customer

Staff/Support

Technology

Work Processes

Organisational Issues

Business Strategy

Business Strategy: The business strategy should be

geared for customer-focus by understanding what customers

want and how this can shape both current and future

products and services offered to them. The customer-

focused strategy should shape subordinate strategies.

Organisational Issues: Commitment is vital from all of

the business divisions. CRM technology selection should

be left to the business leaders who are likely to have a

better understanding of the business strategy as opposed

to specific IT objectives alone.

Staff/Support: All areas of the business should be provided

with excellent levels of support and training both initially and on

an ongoing basis. It is important that an emphasis on

customer retention is made over the more traditional customer

acquisition approach.

Technology: All system platforms should be integrated

or compatible. This will ensure that data from disparate

sources will be consolidated to one source. This will

ensure that there is an accurate and complete repository

of customer and product information.

Work Processes: Business processes and tasks

should be examined for inefficiencies and should be

realigned for customer-focus.

The Customer Centricity Model

Fi

g

ure 2: A ‘Customer Centricit

y

’ Model

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT IN AN ELECTRONIC ECONOMY

105

speed and precision of data recorded is improved

and employees are able to be more flexible by

gaining access to role specific information on the

move and in a more accurate and timely manner.

This improves customer service levels, shortens

decision-making processes and can potentially

become a new source of revenue. The application of

a centralised e-business for a large UK travel

company supported by Virtual Private Networking

(VPN) has allowed a CRM trial to show increased

sales of £150k, which if applied throughout the

business would increase sales by £1.2m per annum

[Shaw and Atkins 2004]. However, the

decentralisation of computer devices increases the

risk to data security and integrity therefore the

implementation of a strict IT policy, adequate user

training and good working etiquette is essential.

3 CUSTOMER SERVICE CRM

Customer service departments are often perceived as

a peripheral activity and are usually seen as a cost to

organisations. In contrast, with growing customer

expectations for reduced response times and

increasing demands for information availability the

role of customer service is crucial for successful

CRM. Research shows that 74 per cent of online

customers would shop elsewhere if their query was

not answered within an hour or so [Dyche 2002].

Customer Service CRM allows an organisation to

have tight control over the services offered by

interpreting each customer’s real value to the

business and providing an appropriate level of

service accordingly. This allows an organisation to

stipulate personalised and profitable customer

retention tactics on a unique, one-to-one basis.

Making appropriate and effective use of the

electronic communication channels can usually

result in a substantial reduction in escalating

customer support costs. In many cases data

administration costs can be transferred to the

customer by allowing them to update their details

over the web. This saves an expensive telephone

operator making the changes on their behalf and

reduces call queue times for customers that do

require operator assistance. Some companies offer

discounts for customers who solely use their online

channels and sometimes direct low-value customers

to self-help sites – UK mobile telephone operator O2

[www.o2.co.uk

] offer its web customers more free

SMS text messages as an incentive to deal with them

solely over the web. An organisation’s website is

becoming a crucial portal for its customers – for

many, it is their first port of call for a query or

problem therefore it is essential it contains a host of

services and information customers expect. This

may include Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),

downloads or detailed product specifications. The

companies who have the best levels of customer

services are those who offer a mix of self-help and

call-centre expertise so that customers are able to

make the choice themselves and not feel isolated.

Tanoury [2003] suggests that customers who contact

call centres symbolise that the organisation has

failed in someway (e.g. product/service failure or

poor self-help content) therefore the contact centre is

an opportunity to salvage a customer relationship.

There are strategic benefits too, Friedlein [2001]

points out that electronic support is also a quick and

easy method of acquiring feedback that can be used

to enhance existing and future products and services.

For those who require operator support, the skills of

call centre staff are vital in meeting customer’s

service expectations. Ultimately, it will determine

whether or not they or their friends and family will

remain loyal. Customer service of the past had been

to provide an efficient but standardised level of

service. Typically, customer service departments

dealt with a wide range of problems using a range of

scripted questions, procedures and rules. The CRM

approach drives flexibility and personalisation – it

encourages and empowers all service staff to make

decisions based on the situation and information

delivered to them on their screens. As such, CRM is

not for those organisations that may want tight

control over every decision made. The challenge of

customer-facing CRM systems is ensuring that

service staff have as much information about the

customer as possible when contact is initiated, as

well as prompting the employee with ‘intelligent’

service recommendations. This will allow them to

personalise conversational details and determine the

flexibility of decisions or procedures with each

customer in person. Figure 3 identifies the many

roles of Customer Service CRM.

The increasing specialisation and importance of

customer service has meant employees need to grasp

relevant expertise for their role. Garland [2002]

suggests that as much as 80 per cent of Customer

Service CRM is about developing people. The

implications of this are the costs and issues

associated with training and maintaining high

service standards. Usually, call centres have a high

staff turnover therefore job variation, enhanced staff

development and good remuneration form decisive

elements to the success of Customer Service CRM.

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

106

4 MARKETING CRM

McKenna [2002] suggests that marketing of the past

had been about “message making” and was far too

concerned with the psychology of brand identity.

Nowadays, marketing becomes much more than a

messaging tool as it attempts to recognise customers

in a growing number of smaller, more specialised

markets. CRM recognises customers’ ‘uniqueness’

– for instance, a group of people who share the same

age range does not mean that they have similar

interests or hobbies. A comprehensive source of

customer information is essential for CRM given

that a large proportion of marketing is analytical. As

well as information available in data warehouses, the

Internet is ideal for this type of unique segmentation

since customer’s ‘click-streams’ (page viewing

history) and purchasing habits can be analysed to

assess product interests and prospective value on an

individual basis. Appropriately, Friedlein [2001]

states that personalisation can differentiate an

organisation at times of growing market similarity.

Some companies use this information to form

personalised home pages containing only products

and services that may be of interest to each

individual customer. Large e-commerce

organisations like Amazon [www.amazon.com

]

collect gigabytes of customer viewing habits

everyday – this cost-effective practice enables them

to identify new marketing and selling opportunities

and extend their range of customer retention tactics.

As a result, companies that have a web presence are

able to cross-sell less obvious products – for

example, comparing customers who have similar

viewing and purchasing habits and attempting to

cross-sell products the other customer had bought

(such as cross-selling across a genre films).

Similarly, Dyche [2002] suggests that the results of

analysing buying trends can be used to selectively

configure products for customers. Complex

products (e.g. PCs) can be configured quite flexibly

over a website to meet each customer’s specific

needs. Product configuration analysis could provide

an organisation with useful information as to what

aspects of customisation customers like to change,

and more importantly, what they change it too (e.g.

customers may upgrade their PC to a specific brand

of graphics card). Over time, the company could

then market a product that contains all the qualities

preferred by its customers; consequently creating a

product that has customer-focused market appeal.

Large data warehouses have enabled organisations

analyse customer attributes and buying behaviour to

make educated predictions as to what they are likely

to buy next. With this knowledge, an organisation

can entice a customer to remain loyal by

recommending products they predict will be sought

after at the right time. In the same way, customer

lifetime modelling enables an organisation to

consider customer value in the long term. Even

though a customer may not be profitable at present,

he or she may be profitable at a later point in life. In

Call Routing

System

$

$

Customer

Customer Service Department

C

u

s

t

o

m

e

r

N

u

m

b

e

r

Customer Service Areas

Billing

Complaints

Order Status

Spare Parts

Warranties

Enquiries

C

a

l

l

t

r

a

n

s

f

e

r

r

e

d

Personalised conversation that may include

searching for information from past purchases

or interactions for use during conversation with

the customer 'on the fly'

Recognition of cross-selling and up-sizing

selling opportunities and offer only when

appropriate

Possession of an in-depth knowledge of

products - both past and present.

Representative has access to all product and

customer information as required

Tailored level of service to the customer's

perceived 'value' to the business and their

situation - e.g. a customer may want to take a

course of action that isn't strictly procedure but

this may be overlooked if they are a particular

profitable or otherwise 'favourable' customer

S

e

r

v

i

c

e

D

e

l

i

v

e

r

y

Operational Database

C

u

s

t

o

m

e

r

D

e

t

a

i

l

s

Customer

information

delivered in

real-time

C

u

s

t

o

m

e

r

P

r

i

o

r

i

t

y

1

5

7

8

4

3

9

10

6

2

3

Note: Numbers in the black boxes indicate the order of a customer service transaction

Customer Data:

1. Name, address etc

2. Contact history

3. Purchase history

4. Cross/Up selling success

5. Credit worthiness

6. Value rating

7. Upcoming events

8. & more

Fi

g

ure 3: Customer Service CRM

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT IN AN ELECTRONIC ECONOMY

107

high street banking, students may not represent high

value accounts initially, however, profitability may

soar in the future when many find themselves in

well-paid employment. It is for this reason that

many high street banks offer undergraduates

incentives to join student bank accounts. Although

this is a more generalised example; large quantities

of accurate customer data, a range of sophisticated

data collection techniques and powerful database

analytics can allow CRM organisations model

customer behaviour and value lifetimes. This can

enable the organisation market its products and

services on a more profitable, one-to-one basis.

Subsequently, the communication links with

customers are important too. Kurtyka [2001]

suggests that the growth of the rapid and cost-

effective electronic channels has enabled marketing

evolve to a two-way communication mechanism and

allows organisations gain an insight to customers’

unique communication preferences – for instance,

the type of communication, the delivery frequency

and the channel it arrives through. Recently, a US

bowling company’s CRM system allowed it to stop

irritating its customers by sending them irrelevant

offers as well as minimise the risk of alienating

those who had already purchased the product

[Dragoon 2002]. In an age where customers are

driven to anguish through electronic ‘spam’ and

other junk mail, it is imperative that customers are

able to determine the basis of communication;

otherwise the organisation risks becoming a major

irritation – proving detrimental to both the brand and

its customer retention programme.

5 SALES CRM

Nowadays, the reality of sales teams is that a range

of time-consuming support tasks constantly hinder

the revenue-generating ability of representatives.

This is supported by Kahle [2000] who states that

typical 30-minute tasks can often take two hours or

more. Add to this, each sales representative has

their own repository of contacts, leads and customer

communication history. This has an adverse effect

on revenues since pockets of knowledge exist across

many different inaccessible sources. As a result,

new leads and opportunities are missed, decision-

making processes are drawn out, support resources

are difficult to locate and neither management,

representatives or customers are able to track

information or indeed, each other. A Sales CRM

system centralises and formalises sales activity and

offers an extensive mix of functionality to maximise

the efficiency of sales teams. A typical CRM

system may:

• Contain an accurate and up-to-date range of

commonly used resources such as pricing details,

document templates, presentations, product

specifications and customer contact information.

• Store a ‘live’ register of leads and opportunities,

as well as relevant market and competition

information to enhance business awareness.

• Contain personal details such as contact

information, weekly diary/schedule and a sales

performance summary.

• Act as an intermediary to accelerate and shorten

bureaucratic decision-making processes – e.g.

product quotations that can be submitted

electronically for approval.

• Be integrated with email, video conferencing and

instant messaging facilities; allowing customers,

suppliers and colleagues to communicate more

easily.

• Provide ad-hoc reporting facilities that are simple

to use, flexible and highly informative.

• Contain other miscellaneous resources such as

hotel information, maps and travel guides.

For data consistency reasons, Sales CRM needs to

be closely integrated with the other operational and

management systems. Chase [2001] suggests that

Sales CRM is allowing organisations collaborate

with internal and external parties so that they are

able to take control of their demand chain. For

example, sales forecasting could be integrated with

manufacturing or supplier inventory systems to

ensure optimal levels of stock. This would enhance

customer satisfaction levels, reduce stock holding

costs and minimise support administration.

Similarly, both suppliers and customers would

benefit from a web-based extranet portal that could

provide them with up-to-date stock information, deal

progress tracking and a communications log. This

would lead to a reduction in common customer

queries that take so much time of a representative’s

typical day.

Besides sales inefficiency, Gardner [2001] suggests

that organisations are not managing each stage of the

sales process in the most effective way. In particular

CRM can optimise one of the pivotal components of

sales activity – personnel. Analysing the

performance of each representative may report the

success rates at the various stages of deals. A CRM

system is then able maximise revenues by matching

individual skills with the outstanding stages of leads

and deals appropriately. For example, good

communicators and negotiators would be more

useful towards the end of the sales process (e.g.

securing a deal). In the same way, each stage of the

lifecycle can be analysed for best practice for others

to copy. In a Sales CRM environment, several

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

108

people end up managing one entire sales cycle and

as a result, sales representatives work together with

shared goals. Unfortunately, as sales divisions are

the most aggressive area of the organisation, gaining

support and cooperation for CRM can be difficult

since fundamental changes may prove detrimental to

levels of personal remuneration (i.e. bonuses and

fringe benefits). This is echoed by McMahon [2003]

who says that most sales representatives are only

concerned about the current situation. This is

because if they didn’t make their existing sales

targets, they wouldn’t be around for the long-term

plans anyway. For this reason, Diver [2002]

suggests that incentives should be adjusted to reward

those who contribute ‘value’ to the CRM system.

6 CRM READINESS

A catalogue of recent CRM failures (65% of CRM

projects during 2001 [Everett 2002]) stresses the

importance of evaluating the feasibility of

implementing CRM. Khera [2000] identified that

well qualified people, well designed processes and

technology are the three vital components for

successful CRM; and whilst some CRM vendors

may claim to offer full CRM solutions, none will be

able to offer all of the above. As a result,

organisations must evaluate whether or not they are

ready for CRM. The CRM Readiness Framework

shown Figure 4 is an approach to categorise aspects

for assessment. The shaded area highlights external

considerations, whilst the non-shaded area

highlights internal considerations:

Market

Economy

Customers

Organisational Culture

Technology Platform

Tasks

Processes

Operational Analysis

Tactical Analysis

Strategic

Analysis

External Forces

Analysis

Figure 4: The CRM Readiness Framework

Below are a series of aspects that could be identified

by exploring the areas suggested by the framework:

External assessment may include:

Economy: current economic conditions, growth

and future trends.

Market: current market position, market

changes and future product line up

and range of competitor products

and services offered.

Customers: future expectations and trends.

Internal assessment may include:

Org. Culture: level of boardroom and employee

support, constraints or availability of

resources for ongoing commitment.

Technology: level of systems integration and/or

compatibility, number of data

sources and quality of existing data.

Processes: communication channels used, levels

of efficiency and computerisation.

Tasks: level of automation, quality of

people and existing alignment for

customer-focus.

This is not an exhaustive list of considerations that

could be identified using the framework – all the

same, the outcome could be one of two things. Not

only could it determine whether an organisation is

ready for CRM, it could also outline areas of

concern that need to be addressed in order to prepare

itself to a state where it is able to implement CRM

with confidence.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Twenty-five years ago, Nolan [1979] proposed a six-

stage growth model containing the various stages an

organisation adopted IT. It is still relevant for

modern day CRM. The final stage of his model –

‘maturity’ – indicates that IT and IS development is

closely tied to strategic business planning and as a

result, is where organisations need to be at before

considering CRM. Organisations need to understand

technological capability with the business strategy in

mind; this minimises the risk of setting unrealistic

objectives that would inevitably result in a poorly

performing implementation. After the early CRM

‘bandwagon’ hype, projects need to be more closely

controlled. Return On Investment (ROI) and other

similar performance indicators are becoming an

essential part of on-going CRM. They enable

organisations to dissect and reflect on its short-term

results so it is able to sustain conformity to the long-

term goals.

Although this paper has discussed some of the more

costly aspects of CRM, many organisations that face

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT IN AN ELECTRONIC ECONOMY

109

limited resources can adopt an incremental approach

to CRM or CRM readiness. Basic changes to

existing systems, work processes and tasks can yield

outstanding results for minimal expenditure – for

example; information that answers common

customer queries could be added to the company

website. Not only will this cut call queue times and

enhance service levels, it will also form a pioneering

part of the organisation’s electronic support strategy

for its Customer Service CRM programme. CRM’s

roots remain in common business sense therefore it

is both economical and practical to examine areas of

the existing business for basic improvements before

venturing onto the more complex and costly aspects

of process redesign and technology investment.

REFERENCES

Alexander, D., Turner, C., 2001. The CRM Pocketbook.

Management Pocketbooks

Chase, P., 2001. Beyond CRM: The Critical Path for

Successful Demand Chain Management. [Online]

Scribe Software Corporation. From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=1670

Delahoz, L., 1999. Leveraging your legacy systems in

pursuit of Customer Relationship Management.

[Online] Montgomery Research. From:

http://www.crmproject.com/documents.asp?d_ID=746

Diver, A., 2002. CRM: May the sales force be with you.

[Online] SAM Magazine. From:

http://www.sammag.com/docs/543.html

Dragoon, A., 2002. Bowling for Customers. [Online] CIO

Magazine. From:

http://www.cio.com/archive/091502/bowling.html

Dyche, J., 2002. The CRM Handbook, 2

nd

Printing,

Addison Wesley

Everett, C., 2002. The problem with customer

relationships. Computer Weekly, 15

th

March 2002

Fickel L., 2001. Unplugged: A wireless odyssey. [Online]

Oracle Magazine, January 2001. From:

http://otn.oracle.com/oramag/index.html

Findlay, C., 2000. CRM: What’s it all about? [Online]

Latitude Solutions Limited. From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=1222

Friedlein, A., 2001. eCRM meets CRM: An Executive

Briefing. [Online] Wheel Group. From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=1296

Gardner, B., 2001. Back to the Front End: Automating the

whole Sales Lifecycle. [Online] Selltis. From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=2249

Garland, C., 2002. CRM: It’s a people thing. [Online]

eCustomer Service World, From:

http://www.ecustomerserviceworld.com/earticlesstore_arti

cles.asp?type=article&id=1551

Kaakani, Z., 2001. Can Mobile OSs Meet e-Business

Needs?. [Online] ADT Magazine, 1

st

January 2001.

From: http://www.adtmag.com/article.asp?id=2671

Kahle, D., 2000. Is your sales system clogged with

accumulated junk? [Online] Sales Lobby. From:

http://www.saleslobby.com/Mag/1200/FEDK.asp

Khanna, S., 2000. Integrating CRM Applications with

Enterprise. [Online] CRM ITToolbox, From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=835

Khera, M., 2000. Customer Relationship Management:

Beyond the Buzz. [Online] United Customer

Management Solutions. From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=430

Kurtyka, J., 2001. Complex Marketing: Why Multi-

channel CRM Really Works. [Online] DM Review

May 2001. From:

http://dmreview.com/master.cfm?NavID=193&EdID=333

7

Manning, I. 2000. Data Warehousing, [Online] From:

http://www.manning.demon.co.uk/

McKenna. R,. 2002. CIO As Marketeer. [Online] Optimise

Magazine/TechWeb Business Technology Network.

From:

http://www.optimizemagazine.com/issue/008/marketing.ht

m

McMahon, T., 2003. CRM, Not the solution. [Online]

DestinationCRM. From:

http://www.destinationcrm.com/articles/default.asp?Articl

eID=3345

Nolan, R., 1979. Managing the crisis in data processing.

Harvard Business Review, March-April, 115-126.

Payne, A., 2000. Customer Relationship Management.

[Online] Key note address to the Inaugural Meeting of

the Customer Management Foundation, London.

From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=9

22

Saran, C., 2003. Survey finds big variation in ERP costs.

Computer Weekly, 6

th

March 2003.

Shaw, R; Atkins, A. S., 2004. Developing an Intranet and

Extranet Business Application for a Large Travel

Agent. ICEIS Portugal, April 2004.

Tanoury, D., 2003. Beyond CRM: A New Strategy for

Service. [Online] CRM ITToolbox, From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=2824

Vellmure, B., 2003. Why bother with Customer Centricity.

[Online] Initium Technology. From:

http://crm.ittoolbox.com/documents/document.asp?i=2778

ICETE 2004 - GLOBAL COMMUNICATION INFORMATION SYSTEMS AND SERVICES

110