MINING CONSUMER OPINIONS ON THE WEB

Organizational Learning from Online Consumer-to-Consumer Interactions

Irene Pollach

Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration, Nordbergstrasse 15, 1090 Vienna, Austria

Keywords: Consumer-to-consumer interactions, data mining, information retrieval, virtual communities.

Abstract: Consumer-opinion websites are becoming important sources of marketing intelligence for companies,

enabling them to turn consumer opinions into opportunities for enhancing customer satisfaction. Grounded

in media richness theory, this paper examines a sample of consumer-opinion websites to identify

mechanisms that render the information disseminated on these websites more suitable for data mining

activities. The results indicate that feedback mechanisms, member profiles, active hyperlinks, and

spellcheckers are means of raising data quality. However, a key challenge for mining consumer opinions

remains the identification and elimination of emotional content such as humor.

1 INTRODUCTION

Before the advent of the Internet, consumers talked

to other people or read consumer magazines when

they wanted to hear other people's opinions on a

particular product or service before or after a

purchase (Korgaonkar and Moschis, 1982).

Consumers have also been found to initiate

conversations with other consumers in commercial

settings to offer advice and information to other

consumers without having been asked for it (Harris

and Baron, 2004).

These interactions have moved to the Web,

where consumer-opinion websites (henceforth C2C

websites) satisfy these communication needs by

providing consumers with the opportunity to find

and share information on products, services, and

brands. The great variety of opinions found on C2C

websites and their advanced search and retrieval

facilities offer clear advantages over face-to-face

communication among consumers (Evans et al.,

2001).

Thanks to the proliferation of consumer-opinion

websites and the persistency of the textual records

consumers produce, companies and consumers alike

can harvest the Web for opinions about particular

products and services (Tapscott and Tiscoll, 2003).

To gather feedback from online consumer

interactions, companies need to understand how

many-to-many communication models function and

how they can capitalize on the information that is

available in these knowledge bases (Maclaran and

Catterall, 2002). Grounded in media richness theory,

this paper seeks to identify mechanisms that render

the information disseminated on C2C websites more

suitable for data mining activities undertaken by

companies.

Previous research on consumer-to-consumer

interactions on the Web has focused on consumer

behaviour in C2C interactions (e.g. Hennig-Thurau

and Walsh, 2003; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004; Chiou

and Cheng, 2003; Xue and Phelps, 2004), C2C e-

commerce (e.g. Nah et al., 2002; Dellarocas, 2003;

Mollenberg, 2004), and trust and reputation systems

in C2C auctions (e.g. Standifird, 2001; Dholakia,

2005; Ono et al., 2003). Several papers have looked

at opinion extraction from C2C sites (e.g. Dave,

Lawrence, and Pennock, 2003; Hu and Liu, 2004;

Chaovalit and Zhou, 2005). However, little attention

has been paid to the interactional facilities on C2C

websites, given that these determine what

information is available in what formats.

2 MINING C2C WEBSITES

On C2C websites, companies may learn about

customer preferences, product defects, service

mishaps, and usability problems on their Web sites

(Nah et al., 2002; Warren, 2002). Ideally, this

129

Pollach I. (2007).

MINING CONSUMER OPINIONS ON THE WEB - Organizational Learning from Online Consumer-to-Consumer Interactions.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Society, e-Business and e-Government /

e-Learning, pages 129-134

DOI: 10.5220/0001275101290134

Copyright

c

SciTePress

negative feedback is translated into opportunities for

companies to meet customer expectations more

closely (Ha, 2002) either in the form of product

modification (Cho et al., 2002) or new product

development (Pitta and Fowler, 2005).

There are a number of challenges inherent in data

mining on consumer-opinion websites. First, the

absence of gate keepers in such interactions means

that anybody with an opinion may post it, even if

s/he does not qualify as a critic, which may have

repercussions on the accuracy and reliability of the

information provided by consumers (Gately, 2000).

The inaccuracy and subjectivity of individual

experiences is generally not a challenge for the

large-scale collection and analysis of consumer

opinions (Turner, 1980). However, problems

encountered in extracting information from

consumer opinions on the Web include the large

amount of very short reviews (Dave, Lawrence, and

Pennock, 2003), people posting personal stories and

adventures with the product rather than an

evaluation of the product's performance (Hu and

Liu, 2004), and information that does not express

opinions or evaluations but provides descriptive

background information about the product

(Chaovalit and Zhou, 2005).

3 METHODOLOGY

The interaction systems available to consumers

wishing to voice their opinion on the WWW have

implications for the usefulness of the data companies

may gather and the tools needed for data mining.

This paper therefore examines interaction formats

found on C2C websites and identifies remedies for

the challenges they pose to data mining.

3.1 Conceptual Framework

This study is grounded in media richness theory,

which argues that a medium's level of richness

determines how effectively messages are conveyed.

This richness depends on four parameters: (1) the

immediacy of feedback, (2) the number of visual and

verbal cues the medium can convey, (3) the variety

of language signs that can be transmitted, and (4) the

possibility of expressing emotions. Face-to-face

communication is considered to be the richest

medium, given that participants receive immediate

feedback, communicate visual and verbal cues, use

natural language and non-verbal language, and can

communicate feelings easily. Electronic media, such

as e-mail, are considered to be leaner than face-to-

face conversations, but richer than static, written

communication, e.g. in the form of letters or faxes

(Daft and Lengel, 1986; Daft et al., 1987; Lengel

and Daft, 1988).

Computer-mediated communication has means

unavailable in conventional written communication,

thus providing richer interactions than non-digital

written formats such as letters or faxes. While

feedback in electronic media is always less

immediate than oral communication, as typing a

message causes a delay in transmission (Dennis and

Kinney, 1998), synchronous interactions are clearly

richer in terms of feedback than asynchronous

interactions. Also, many of the social cues we are

used to in the physical world are absent in online

interactions, e.g. physical appearance, voice,

intonation, facial expression etc. (Donath, 1999).

Thus, online self-presentation is reduced to

communication style and word choice, unless people

decide to explicitly reveal details about themselves

(Hancock and Dunham, 2001). Similarly, emotions

in computer-mediated interactions have to be made

explicit to be conveyed, which is typically done by

means of iconic strings of ASCII characters

("emoticons") (Bolter, 1996).

3.2 Data

The sample Web sites were found in the Yahoo di-

rectory under "Consumer Opinion" (Yahoo, 2005),

which contained links to 32 C2C Web sites in Janu-

ary 2005. Seven of them were not available at the

time of data collection, four provided information

for consumers but did not facilitate C2C interac-

tions, one was in Spanish, and one was just an alter-

native URL to another site listed in the directory.

These sites were thus eliminated, which resulted in a

sample of 19 Web sites (see Table 2). A user ac-

count was opened with each site in order to gain

access to all features the site offers. The interactional

tools and facilities of the first nine Web sites were

explored to identify those that offer richness in terms

of feedback, multiple cues, language variety, and

personal focus. A list of 25 features was drawn up

(see Table 1) and all 19 sites were examined for the

presence of absence of these features, which follows

the methodology of previous website analyses (cf.

Robbins and Stylianou, 2003; Zhou, 2004).

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

130

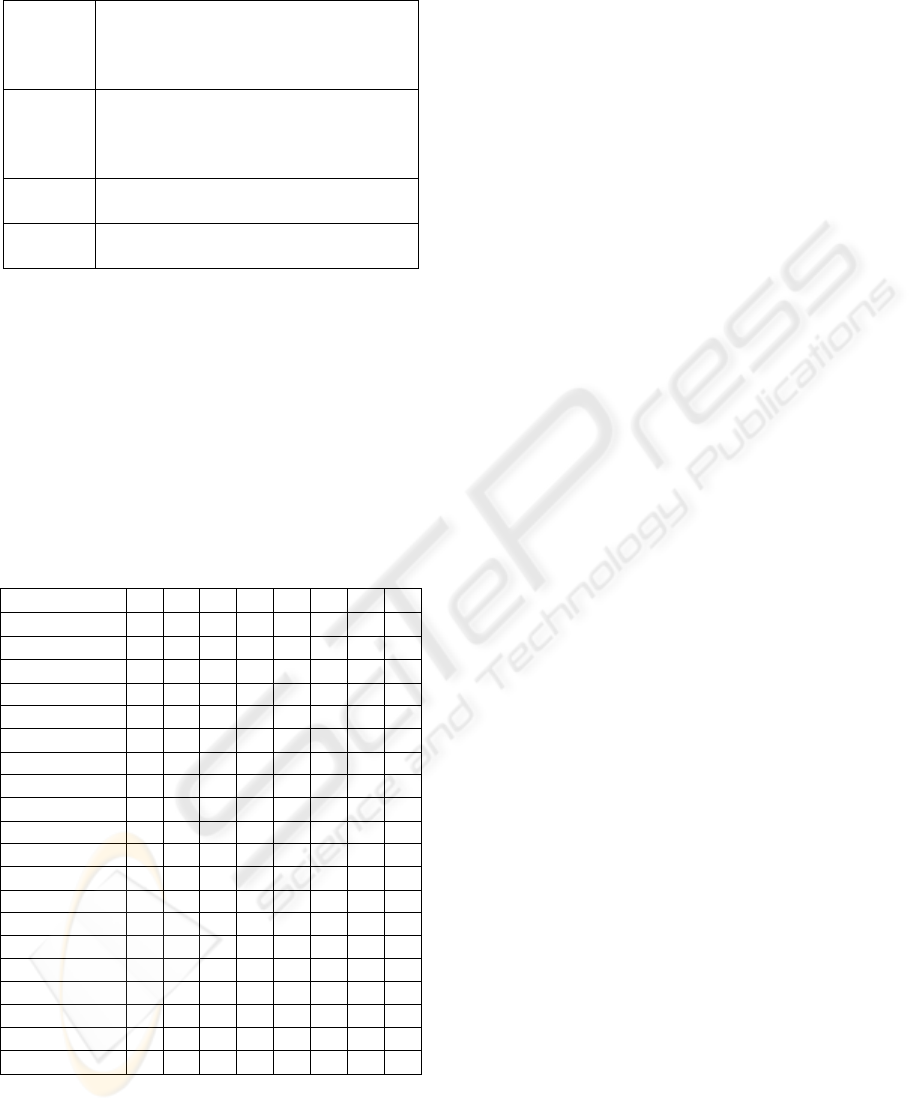

Table 1: List of features.

Feedback Asynchronous/synchronous, ratings,

comments, threads, PM, e-mail, chats,

rebuttals, feedback from site owner,

credit points

Cues Contents of member profiles, user

statistics made available, link to personal

site, picture of oneself, network of trust,

ranking of contributors, titles awarded

Language Ratings, verbal comments, activated

hyperlinks, pictures

Personal

focus

Registration, screen name, avatar,

emotive icons

4 RESULTS

The 19 C2C sites differ substantially in the interac-

tion formats they offer. As Table 2 shows, the sites

enable consumers to express themselves in a variety

of formats, including discussion threads (DI), com-

plaints (CO), chats (CH), product reviews (RE),

questions (QU), product ratings (RA), consumer

blogs (BL), and wikis (WK).

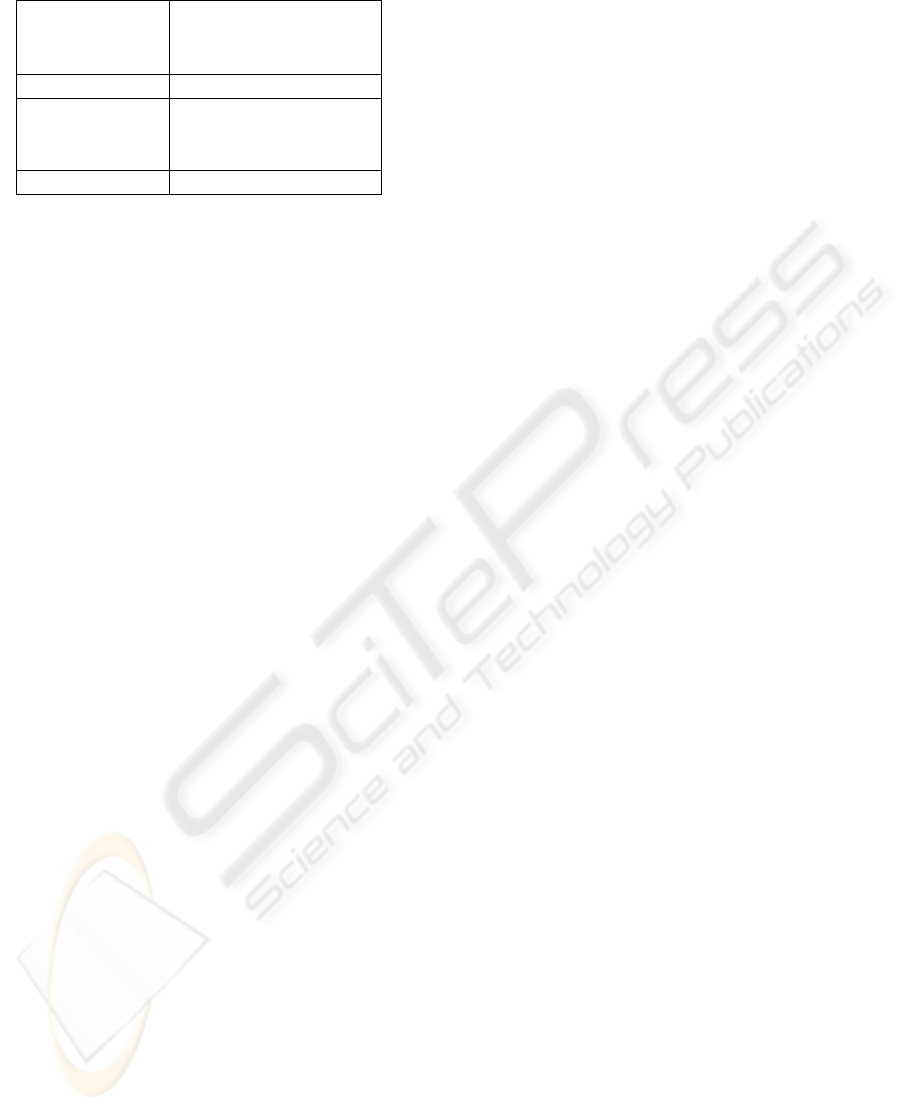

Table 2: Basic interaction formats.

DI CO CH RE QU RA BL WK

AskAnOwner

y

ComplaintBook

y

Complaints

y

ConsumerReview

y

y

Dooyoo

y

Epinions

y

y

JudysBook

y y

MarketMarks

y

y y

My3cents

y y

y

y

PlanetFeedback

y

y y

Ratings

y

y

ReviewCentre

y

y

y

Riffs

y y

y y y

RipOffReport

y

SafetyForum

y

SqueakyWheel

y

SyllasForum

y

TCCL

y y y y

uSpeakOut

y

TOTAL

8 8 2 11 4 3 2 1

4.1 Feedback

The 19 sites use almost exclusively asynchronous

feedback mechanisms. In fact, TCCL and Riffs are

the only websites facilitating synchronous feedback

in the form of online chats. Asynchronous feedback

on C2C websites includes comments on product

reviews (12), e-mails (10), ratings of the usefulness

of a product review (9), replies in discussion threads

(8), company rebuttals to complaints (6), personal

messages among registered users (6), replies to

questions (4), and wiki collaborations (1).

Feedback facilities can also be looked at in terms

of the parties involved. While only eleven sites offer

one-to-one consumer communication (i.e. PM, e-

mail, chat), 16 sites post one-to-many feedback from

consumers (i.e. ratings, comments, replies in

threads) and six sites enable companies to provide

feedback on consumers' opinions in the form of

rebuttals. Only one C2C website does not offer any

feedback mechanisms at all, confining interactions

to message transmission and reception.

To some extent, also the operators of the C2C

sites give feedback to the contributors. While some

of them merely claim that they reserve the right to

remove inappropriate or offensive messages, two

sites claim to approve all reviews before they post

them, and two websites automatically screen all

messages for offensive words and censor them.

While the majority of sites rely on voluntary

contributions, six sites offer financial or material

incentives to contributors, which also function as a

feedback mechanism. The incentives offered include

cash rewards for every 100th review submitted by

registered members or credit points which are

redeemable for products or cash and are earned for

each review written or each time the review is read.

4.2 Multiplicity of Cues

Allowing members to provide information about

themselves when they register is one way to remedy

the Web’s reduced capacity to convey social cues.

Twelve sites enable users to make such information

available in their member profiles, including

information such as location, gender, occupation, e-

mail addresses, verbal biographies, hobbies, and

links to personal websites. On ten sites, user profiles

also include statistics about the user's activities on

the site, e.g. the number of contributions by the user,

the join date, the number of credit points earned, the

average rating s/he has received for his/her

contributions, the number of visits, the date of the

last visit, and the average response time.

C2C sites also provide cues regarding the status

of individual users in C2C communities. Two sites

provide rankings of their contributors either on the

basis of the number of credit points they have earned

or on the number of contributions they have made to

MINING CONSUMER OPINIONS ON THE WEB - Organizational Learning from Online Consumer-to-Consumer

Interactions

131

the site. Six other sites award titles based on the

quality (e.g. top reviewer) and quantity (e.g. senior

member) of users' contributions. ReviewCentre does

not award titles to users but to their contributions,

labeling high-quality reviews as expert reviews.

Similarly, registered members on Dooyoo can

nominate reviews for inclusion in the site's Hall of

Fame.

Another way of determining a user's status in a

C2C community is by enabling registered members

to indicate in their profiles which users in the

community they trust in terms of expertise. These

buddy networks people create when they add people

to their list of trusted members also indicted who a

user is trusted by and thus may help others to decide

whether or not to trust a reviewer. Overall, four sites

offer such reputation systems. One C2C site merely

lists a user's Friends but does not indicate how many

users have added this user to their list of Friends.

4.3 Language Variety

All 19 C2C sites enable people to articulate their

opinions publicly using natural language, e.g.

discussion threads, blogs, chats, product reviews,

comments, questions and answers, complaints and

praises. The texts can be enhanced with active

hyperlinks on six sites, e.g. to link to the sites of

companies or products that writers are reviewing.

Six sites also enable writers to paste pictures into

their messages. Similar to hyperlinks, pictures may

help people to provide evidence for their arguments

for or against a company or a product. Three

websites inviting verbal reviews offer a default

structure that encourages readers to deal with

positive and negative aspects of a product in their

review.

Eight sites use categories in addition to verbal

statements in the form of Likert-scale questions or

closed-ended questions. These communication

formats clearly limit people's means of expression to

a pre-defined set of answers and introduce a

response bias as they suggest ideas and cannot

account for qualifications to responses (Blunch,

1984). Such ratings appear in two different formats.

First, people can rate products or companies

according to predefined criteria (e.g. customer

service, ease of use, etc.). Second, they can rate the

usefulness of other consumers' contributions, e.g.

"Was this review very helpful / helpful / somewhat

helpful / not helpful to you?". Although such data

can be analyzed more easily than verbal product

reviews, they provide only meaningful information

if large numbers of users make use of these

facilities.

4.4 Personal Focus

Six of the C2C websites enable people to use a

selection of emotive icons to express sentiments

such as fear, boredom or uncertainty, which

sequences of ASCII characters do not convey as

unequivocally as icons. Thus, such interactions are

richer than those in which people can use either only

ASCII-code emoticons in texts or no emoticons at

all because opinions are to be expressed in the form

of ratings. Another factor determining how much

presence a writer has in computer-mediated

communication is whether or not they post their

contributions anonymously, use a screen name, or

use their real names. On four sites people can voice

their opinions anonymously, on three sites they are

strongly encouraged to use their real names, and on

twelve sites they can register any name. Consumers

thus have the possibility to express feelings,

emotions and attitudes when they select screen

names. Avatars, which enable people to express

emotions and attitudes visually, can only be used on

five C2C sites. Thus, in the C2C interaction systems

studied, interlocutors do not have much visual

presence, although the medium has the capabilities

to do so.

5 DISCUSSION

As the above results have shown, the Web sites

examined have implemented a number of measures

that may render contributions to these sites more

useful for data mining activities. Table 3

summarizes these measures, indicating which

parameter of media richness they pertain to and how

many sites have implemented them.

First, the quality of data stored and disseminated

on C2C websites could be improved through

measures pertaining to feedback, cues, language, and

personal focus. Feedback mechanisms may impact

quality, since people are likely to try harder when

they know other people can rate them or comment

on what they have written. Similarly, writers might

pay more attention to quality when site owners

review contributions before they make them

available publicly or may even decide not to post

them.

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

132

Table 3: Meeting the challenges of C2C data mining.

Feedback Ratings by readers (7)

Reader comments (11)

Screening/reviewing (3)

Cues Member profiles (11)

Language Verbal expression (18)

Active hyperlinks (6)

Spellchecker (1)

Personal focus Emotive icons (6)

Further, cues users communicate in member

profiles decrease the anonymity inherent in online

interactions, in particular, if such member profiles

contain links to users' personal Web sites. If writers

are given the opportunity to post information about

themselves in such profiles, they might be less likely

to include social information, which is irrelevant to

corporate data mining efforts, in product reviews.

Member profiles on C2C websites thus reduce

'noise' in the information that can be extracted.

Data quality is enhanced when opinions are

expressed verbally, since verbal statements can

account for both positive and negative views on a

product or a company and qualify the level of

enthusiasm or disappointment, unlike opinions

expressed by answering multiple choice questions or

closed-ended questions. Further, active hyperlinks

may enhance the quality of contributions in C2C

interactions, as they enable the writer to loosely

integrate information from other sources, giving a

broader picture than the information posted on one

C2C Web site can give. These active hyperlinks

could be followed by data mining tools and

integrated into the analysis as well, though probably

in a separate run in order not to distort the original

dataset obtained from a C2C site. Spellcheckers

would help writers to correct their spelling mistakes,

which would also improve the results of data mining

efforts, as wrongly spelt words may not be

accounted for in data mining, unless spelling is

corrected by the researcher first.

Ultimately, data quality in C2C interactions can

be enhanced by enabling people to express feelings

and attitudes using emotive icons. These graphic

icons are able to express far more emotive states

than emoticons produced with ASCII characters and

thus may shorten or eliminate passages verbalizing

emotions in consumers' contributions. Thus, emotive

icons are able to make messages more concise by

capturing emotive content and leaving only product-

related information in the text. However, this also

entails that these icons – unlike ASCII emoticons –

cannot be interpreted correctly when mining these

data. For example, writers in electronic

environments would typically use emoticons to

indicate the humorous intent of a statement, which

can be detected and eliminated if ASCII emoticons

are used but not if icons are used.

The study conducted has two limitations. First,

the sample was drawn from a Web directory, which

may not include an exhaustive list of consumer-

opinion websites. Second, all sites included in the

sample were in English, since websites in languages

other than English were excluded from the sample in

order to draw a linguistically homogenous sample.

Future research may build on the results of this

study, using the features identified as a basis for

studying sites in non-English speaking countries.

More importantly, consumers who are active on

C2C websites should be surveyed about the ways in

which they make use of the features identified in this

study and their perceptions of richness and social

presence. Such studies should also account for

cultural differences regarding the use of consumer-

opinion websites in general.

REFERENCES

Bolter, J. D., 1996. Virtual reality and the redefinition of

self. In L. Strate, R. Jacobson, and S.B. Gibson (Eds.),

Communication and Cyberspace. Social Interaction in

an Electronic Environment (pp. 105-119). Cresskill,

NJ: Hampton Press.

Chaovalit, P., Zhou, L., 2005. Movie review mining: A

comparison between supervised and unsupervised

classification approaches. In Proceedings of the 38th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Los Alamitos: Computer Society Press.

Chiou, J.-S., Cheng, C., 2003. Should a company have

message boards on its Web sites? In Journal of

Interactive Marketing, 17(3), 50-61.

Cho, Y., Im, I., Hiltz, R., Fjermestad, J., 2002. An analysis

of online customer complaints: Implications for Web

complaint management. In Proceedings of the 35th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

Los Alamitos: IEEE Press.

Daft, R.L., Lengel, R.H., 1986. Organizational

information requirements, media richness and

structural design. In Management Science, 32(5), 554-

571.

Daft, R.L., Lengel, R.H., Trevino, L.K., 1987. Message

equivocality, media selection, and manager

performance: Implications for information systems. In

MIS Quarterly, 11(3), 355-366.

Dave, KI., Lawrence, S., Pennock, D.M., 2003. Mining

the peanut gallery: Opinion extraction and semantic

classification of product reviews. In Proceedings of

the 12th International World Wide Web Conference,

http://www2003.org/cdrom/html/ refereed/index.html.

MINING CONSUMER OPINIONS ON THE WEB - Organizational Learning from Online Consumer-to-Consumer

Interactions

133

Dellarocas, C., 2003. The digitization of word of mouth:

Promise and challenges of online feedback

mechanisms. In Management Science, 49(10), 1407-

1424.

Dellarocas, C., 2005. Strategic manipulation of Internet

opinion forums: Implications for consumers and firms.

MIT Sloan Working Paper No. 4501-04.

Dennis, A.R., Kinney, S.T., 1998. Testing media richness

theory in the new media: The effects of cues,

feedback, and task equivocality. In Information

Systems Research, 9(3), 256-274.

Dholakia, U.M., 2005. The usefulness of bidders'

reputation ratings to sellers in online auctions. In

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(1), 31-40.

Donath, J. S., 1999. Identity and deception in the virtual

community. In M.A. Smith and P. Kollock (Eds.),

Communities in Cyberspace (pp. 29-59). London:

Routledge.

Evans, M., Wedande, G., Ralston, L., van 't Hul. S., 2001.

Consumer interaction in the virtual era: Some

qualitative insights. In Qualitative Market Research,

4(3), 150-159.

Ha, H.-Y., 2002. The effects of consumer risk perception

on pre-purchase information in online auctions: Brand,

word-of-mouth, and customized information. In

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8(1),

http://jcmc.indiana.edu.

Hancock, J.T., Dunham, P.J., 2001. Impression formation

in computer-mediated communication revisited. An

analysis of the breadth and intensity of impressions. In

Communication Research, 28(3), 325-347.

Harris, K., Baron, S., 2004. Consumer-to-consumer

conversations in service settings. In Journal of Service

Research, 6(3), 287-303.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Walsh, G., 2003. Electronic word-of-

mouth: Motives for and consequences of reading

customer articulations on the Internet. In International

Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8(2), 51-74.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K.P., Walsh, G., Gremler,

D.D., 2004. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-

opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to

articulate themselves on the Internet? In Journal of

Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 39-52.

Herring, S. C., 1999. Interactional coherence in CMC. In

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 4(4).

http://jcmc.indiana.edu.

Hu, M., Liu, B., 2004. Mining opinion features in

customer reviews. In Proceedings of Nineteenth

National Conference on Artificial Intelligence. AAAI

Press.

Korgaonkar, P., Moschis, G.P., 1982. An experimental

study of cognitive dissonance, product involvement,

expectations, performance and consumer judgement of

product performance. In Journal of Advertising, 11(3),

32-44.

Leimeister, J.M., Krcmar, H., 2005. Evaluation of a

systematic design for a virtual patient community. In

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication,

10(4), http://jcmc.indiana.edu.

Lengel, R.H., Daft, R.L., 1988. The selection of

communication media as an executive skill. In The

Academy of Management Executive, 11(3), 225-232.

Maclaran, P., Catterall, M., 2002. Researching the social

Web: Marketing information from virtual commu-

nities. In Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 20(6),

319-326.

Mollenberg, A., 2004. Internet auctions in marketing: The

consumer perspective. In Electronic Markets, 14(4),

360-371.

Nah, F., Siau, K., Tian, Y., Ling, M., 2002. Knowledge

management mechanisms in e-commerce: A study of

online retailing and auction sites. In The Journal of

Computer Information Systems, 42(5), 119-128.

Ono, C., Nishiyama, S., Kim, K., Paulson, B.C., Cutkosky,

M., Petrie, C.J., 2003. Trust-based facilitator:

Handling word-of-mouth trust for agent-based e-

commerce. In Electronic Commerce Research, 3(3/4),

201-220.

Pitta, D.A., Fowler, D., 2005. Online consumer communi-

ties and their value to new product developers. In The

Journal of Product and Brand Management, 14(4/5),

283-291.

Robbins, S.S., Stylianou, A.C., 2003. Global corporate

web sites: an empirical investigation of content and

design. In Information & Management, 40, 205-212.

Standifird, S.S., 2001. Reputation and e-commerce: eBay

auctions and the asymmetrical impact of positive and

negative ratings. In Journal of Management, 27, 279-

295.

Tapscott, D., Tiscoll, D., 2003. The customer peers back.

In Intelligent Enterprise, 10 December, 22-30.

Turner, A., 1980. Systematically acquiring verbal

information. In Optimum, 11(1), 52-57.

Warren, S., 2002. Selling strategies – corporate

intelligence – i-spy: Getting the lowdown on your

competition is just a few clicks away. In Wall Street

Journal, 14 January, R14.

Xue, F., Phelps, J.E., 2004. Internet-facilitated consumer-

to-consumer communication. In International Journal

of Internet Marketing and Advertising, 1(2), 121-136.

Yahoo, 2005. Consumer Opinion, http://dir.yahoo.com/

society_and_culture/issues_and_causes/consumer_adv

ocacy_and_information/consumer_opinion/.

Zhou, X., 2004. E-government in China: A content

analysis of national and provincial Web sites. In

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 9(4),

http://jcmc.indiana.edu.

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

134