Decision Support by Handling Experience Feedback of Crisis

Situations

Mohamed Sediri

1

, Nada Matta

1

, Sophie Loriette

1

and Alain Hugerot

2

1

ICD/Tech-CICO, Université de Technologie de Troyes, 12 rue Marie Curie, BP. 2060, 10010, Troyes Cedex, France

2

PhMD SAMU, 10 Emergency Department, 101 avenue A. France, 10003, Troyes Cedex, France

Keywords: Engineering and Management, Experience and Situations Representations, Emergency Crisis Management,

Scenarios, Decision Making under Stress, Time, Space, Task Dependence.

Abstract: The medical services have a key role when the crisis endangers lives. The surprising events and the time

pressure render the decisions more crucial and interventions become more complex. A lot of progress has

been made about this issue, such as improving emergency services in hospitals and establishing cell crises,

defining general and specific plans of intervention and ministerial circulars awareness to deal with most

common threats. But, challenges of optimality, decisions speed, and interventions effectiveness are still

present. These problems have, in general, three issues; communication, coordination and loss of

information. We present in this paper our results related to the definition of structure and interfaces in order

to handle experience of crisis management. The aim is to define a decision making environment based on

the emergency experience feedback (Experience representation and use).

1 INTRODUCTION

The decision makers in emergency department team

are faced with major crises; they manage big

disorganizing and destabilizing situations. In order

to preserve human life, they project during the short

time of the emergency in the imperative to act

quickly. Consequently, the decision is under an

enormous stress. It can cause prolonged inhibition or

impulsivity slowing the process of reasoning. Other

effects are so damaging: the communication and

coordination. Therefore, in order to avoid repeated

mistakes and acting more appropriately, they need

right information at the right moment; these pieces

of information are related to the crisis context,

experience feedback of previous situations and

logistics management. We present in this study our

first result aimed at representing emergency

management situations based on experience

feedback. Several dimensions are considered in this

study: organization, communication decision making

and problem solving activities.

As we are unable to prevent or anticipate

disasters sufficiently, optimal management of such

eventual situation is necessary. We have to think

first about the means and methods of recognizing

situations and provide training for stakeholders to

ensure pertinent decisions and effective

interventions. Crisis management consists in dealing

with the complexity and the interdependency of

systems (Birregah and Muller, 2012; Smith and

Elliott, 2005; Lagadec, 1993) and especially with the

combination of events. Some researchers define

approaches and techniques in order to define criteria

to help to assess the vulnerability of systems

(Whybo, 2010), they define organizations and

communications guidelines in order to avoid

vulnerability and deal with the crisis with minor

consequences.

Our study focuses on crisis management in

medical contexts. In fact, medical services have a

key role when the crisis endangers lives. The

unexpected events and the time pressure render the

decisions more crucial (Sommer, 2012) and

intervention become more complex. A lot of

progress has been made in this issue, such as

improving emergency services in hospitals and the

establishment of cell crises, definition of general and

specific plans of intervention and ministerial

circulars awareness to deal with most common

threats (Couty, 2004). But, the problems of the

optimality of decisions speed and effectiveness of

interventions are still present. Those issues have, in

general, three axis; communication, coordination

and loss of information.

351

Sediri M., Matta N., Loriette S. and Hugerot A..

Decision Support by Handling Experience Feedback of Crisis Situations.

DOI: 10.5220/0004545003510359

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval and the International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2013), pages 351-359

ISBN: 978-989-8565-75-4

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 RELATED WORKS

Several theories design decision support in the crisis.

The authors propose several psychological aspects

of crisis managers and the organizations that are

faced with these situations (Turoff et al., 2004). The

evaluation of proposals approaches provides rather

inconclusive results. Other approaches that attempt

to design a perfect system can be found in the works

of French and Turoff (French and Turoff, 2007).

These works attempt to study decision making

process in crisis situation, as well as filling the gaps

of the systems supposed manage it. Hale (Hale,

1997) and Carver (Carver and Turoff, 2007) offer a

part of their architecture to communication aspect

between actors, Caver aim to provide models for a

perfect communication between human actors and

software as a single team. Finally Kim (Kim et al.,

2007) proposed the CIMS system for critical

situations. This system is more focused on the

problem of communication taking into account a

number of small significant problems.

Other systems are focused on representing the

operational, organizational and communicational

levels (Smith and Elliott, 2005); these solutions are

either general approach (Oomes, 2004) or rigorous

techniques adapted to specific situations. (Sell and

Braun, 2009) the most commonly used techniques

and methods are based on modeling workflow

(Schoenharl et al., 2006), GIS, multi-agent systems

and rule-based systems (Johnson, 2000).

Recently, others intersecting works are

introduced. These works propose another point of

view using new techniques such as, case-based

reasoning (Moehrle, 2012) and knowledge

anthologies (Otim, 2006; Chakraborty et al., 2010).

The limitation of these proposition is that they are

either very small or they define many concepts that

are not shared between other crisis situation;

therefore they are not adapted to the dynamic aspect

of this kind of situation.

3 CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Crisis management is a special type of collaborative

approach in which the actors are subject to an

uninterrupted stress. It requires succeeding because

the consequences are important (human and

economic losses). Crisis differs from an emergency

situation by its destabilizing effects (Lagadec, 1993)

"emergency plus destabilization," an emergency is

an event for which intervention procedures are

known specialties requirements are clearly

identified, and roles and responsibilities are clearly

divided.

A variety of approaches has been identified to

deal with a crisis and can be classified in three

categories (Smith and Elliott, 2005; Lagadec, 1993).

In the first category, we can note the model

presented by Ian Mitroff and Pauchan Thierry, it is a

model of identification, one of their axes identifies

characteristics "internal" or "external” while the

other highlight the dimensions "Technical /

Economic" or "Human / Social / Organizational."

The second category focuses more on a set of points

that characterize the crisis as a result of events and

behaviours. The eventual effects caused by this

situation in terms of pressure on people supposed to

manage it, its consequences on the environment and

the difficulty of adopting adequate responses to

many concerns. The last category includes

approaches, called synthetic. It aims to give general

definitions for the crisis in terms of threats to the

objectives of stakeholders and critical choices facing

the surprising events in the crisis situations.

The authors have identified a set of common

phases in the management of crisis situations

(Johnson, 2000; Lagadec, 1993; Oomes, 2004); to

summarize, we can identify three major phases that

can occur cyclically:

• Preparation: through the classification of

situations, training and exercises, scripting events,

identification of critical sites, structuring and

computerization of library resources and the

definition of roles and tasks for structuring

feedback.

• Intervention / handling: The phases from alert to

system stabilization. It consists in four basic steps:

• Identification of the situation.

• Logistics and implementation of emergency on

site.

• The evacuation, reception and support of victims

in institutional care.

• The drafting of the comprehensive review.

• Analysis/ Feedback: learning from real-life

situations. This assessment is critical to improve

the response strategy. It will therefore help us

describe the types of situations more precisely and

enrich the feedback structure.

Through these three phases, we found the

importance of experience feedback in order to deal

with crisis situations. In our work, we use

knowledge engineering and management of

knowledge to face the problems of the three phases

described above.

In dealing with crisis, decision makers attempt to

identify or anticipate potential events that can occur,

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

352

also the important moment, or incidents, that may

trouble in an effort to develop actions and measures

intended to avoid other incident to evolve into a

current crisis (Smith and Elliott, 2005). These

elements are attached to the crisis context that

influences the initial followed reasoning and

decision making strategies.

Until today, a lot of research work has been done

about the influence of context during the reasoning

and decision making process. A non-integral

perception of the environment may lead to limited

inferences. This process is strongly influenced by

the information received through sensorial registers,

as well as the memory capacity. In consequence, any

useful information will interact with inferential

processes during (Van der henst, 2002) premises

processing. Tulving (1976) (Richard, 1998) was the

first to draw attention to this phenomenon; he

introduced the concept of specific encoding (the

success of recovery depends on the proximity

between encoding and recall context). An

inefficiency context representation and perception

may influence the actor’s point of view and build

inappropriate decisions.

Moreover, the analogy reasoning is an essential

activity in dealing with crisis situation, which leads

us to use the techniques defined by the CBR for

recognition and representation of situations. The

term analogy (Reed, 2011; Richard, 1998) is used in

expression “reasoning by analogy” that is a general

heuristic for assumptions forging. It refers to the

form of reasoning that is involved in a task, used

extensively in the psychometric tests. It also means

the transfer of meaning from one domain to another.

Moreover, it consists in reusing a known situation

from other similar situations (Reed, 2011; Richard,

1998). The analogy is a central activity in the human

life. We use it every day when faced with unknown

situations. It allows dealing with the unknown from

what is already known. Pedagogically, it is the most

natural and the easiest way of reasoning.

According to Gentner and Toupin (1986), the

analogy (Reed, 2011), is based on a general and

calculated similarity between a source and a target.

There are three kinds of similarities: attribute

similarities, similarities between low-order

relationships and between high-order relationships.

To make the analogy, we need to match our current

situation (called base) with another past situation

(called target) based on the similarities of high rank.

Commonly, in crisis situation the similarity among

situations can be estimated using metrics and

considering that cases are represented as attribute-

value pairs (the number of victims, localization,

accident type, homogeneity, etc). The other

techniques can be used such as looking in semantic

field of some indicators. Thus, we are interested in

developing an algorithm that could provide results

within a reasonable response time. It must also be

suited to this kind of non-formal situations.

Finally, crisis management is a cooperative

activity. Therefore, we also study Computer-

Supported Cooperative Work to process

communication and coordination (Shmidt and

Simone, 1996) in such situations.

4 OUR METHOD OF WORK

In an informal field like crisis, case-based analysis

(Burke et al., 2000) seems to be the best approach,

because the actors express their knowledge through

a set of real-life situations. So, we use the techniques

of case-based reasoning (CBR) (Kolodner, 1993)

and especially the description of situations to define

a structure of crisis representation taking into

account the context of resolution. Similarly, the type

of underlying reasoning in CBR systems can be

based on an analogy of situations (Reed, 2011; Aich

and Loriette, 2007), very useful in the recognition of

crisis situations.

Moreover, in our work, we need to represent a

feedback of these situations. This experience is

generally owned by the actors of the emergency

sector, as well as the documents and reports

prepared or produced as a result of such

intervention. Knowledge Engineering provides

techniques to represent expertise in problem solving

(Reed, 2011; Richard, 1998). These techniques

allow highlighting key points as objectives or

reasons for such actions of the experts. Several

techniques of interview issued from knowledge

management and engineering are used to

communicate with experts in order to understand

and represent rules and concepts used in crisis

management experiences.

The cooperative aspect must be considered

including coordination, communication and

cooperative problem solving in order to specify

several actors with different objectives who are

involved in crisis management (Reed, 2011;

Richard, 1998; Shmidt and Simone, 1996). In this

project, we studied the dimensions of coordination

and communication conducted by a single type of

actor: the Emergency Department. Cooperative

decision making in a crisis where other types of

actors are involved (the prefecture, fire-fighters,

police,) is not studied in this work.

DecisionSupportbyHandlingExperienceFeedbackofCrisisSituations

353

To sum up, the different aspects considered in

our work are (Sediri et al., 2013):

Representation of the context of the situation:

environmental information and available

resources.

Dynamic representation of the problem-solving

considering the evolution of situation.

Successes and failures pointed on each

intervention as well as rules and concepts.

Identification of the types of situations and criteria

for recognition of these situations.

Representation of the communication between the

actors within the spatial dimension (various

locations).

Coordination in actions as well as human and

material logistics.

Our results are based on several meetings with

actors in the emergency department of the Troyes’

hospital; the emergency doctors, assistants and the

specialists who have experience in real crisis

situation and training exercises. First interviews

were general and helped to identify main problems

and discover the domain, Next ones aimed at

describing a specific situation like road accident,

intervention on an infirmary establishment because

of a fire alarm and a nuclear accident exercise.

5 ANALYSIS OF CRISIS

SITUATIONS

The space (place) is a major dimension of crisis

management; the representation of the organization

of actors in relation to the space will help, in one

hand, to clarify the type of existing communication

and vision that each actor has of the situation. In the

other hand it makes more clearly the manner in

which we make sense of crisis events and issues

around problems associated with managing the acute

phases of a crisis, as well as dealing with its

location, setting, victims destination and its

aftermath. Three main places have been identified

(Sediri et al., 2012; Matta et al., 2012):

The Crisis Cell: the place of the control and the

orchestration of the intervention, its most

important roles are managing the material and

human resources. The link with outside and the

responsible of emergency department (the rear

base) is done by the communication center.

Crisis Site: The area affected by the event, it

includes actors such as the first medical team and

advanced medical and other professionals.

Emergencies/hospitals: These services receive

victims and their families and ensure their follow-

up. The rear base, depending on the distance of

crisis site and or available places and required

specialties for each victim, achieves the choice of

the orientation of the victims.

Several actors of emergency department are

involved in crisis situation: doctors, first aids

rescuers, assistants, secretaries etc. According to the

work place and situation ‘s state, each actor is in

contact with other professional of the domain such

as police, state services, government delegates, etc

( Figure 1). So, the communication and organization

dimensions have to be considered to represent this

type of situations.

CommunicationCenter

Responsible

Doctors

EmergencyCenter

EmergencyDepartment

Responsible

Secretary

Ambulance

AccidentPlace

FirstEmergencyPost

Responsible

Nurse

Rescuer

SecondEmergencyPost

Responsible

Secretary

Ambulances

Hospital Place

Reception Team

Responsible

Secretary

Admission

Secretary

Crisis Unit

Emergency

Delegate

State

Delegate

Police

Delegate

FireFighter

Delegate

Figure 1: Actors’ organization seen from the space

dimension.

For better configuration of the actor tasks, the time

dimension is very important in crisis management

not only in terms of life preserving as a final

objective. But it has also a major importance on each

episode during the intervention. It must be

considered so as to provide (Sediri et al., 2012) to

decision makers an empirical and control

environment in which they can have an overview of

what happens in terms of tasks and actions duration,

what must be done or what should be done

immediately etc.

Experts identify different types of situations to

represent and we work with them for acquiring

experience and definition of common structures

(Sediri et al., 2012) to represent this experience.

They are looking forward to promote the reuse of

this experience and acquiring a future one Thus, we

propose a structure that include, chronologically,

actor tasks and faced problems during an

intervention (Figure 2).

The aim of this structure is to represent the

different communication links established during the

crisis intervention and nature of its exchange. In

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

354

t

0

• Localization:

• RoadType

• Access

• AccidentElements:

• Vehicles NBandType

Problems:

• Localization :address confusionor

flouifHighway =>Loss Timeto

access

• Loss Time=>moreSerious Victims

Communication

Center

AccidentAlert

10‐15Minutes

Send First

Emergency

Post

First

Emergency

Post

Needs ofMaterials,resources

Victims NB,serious,etc.

• Logistics of:

• Gather Materials

• Solicit EmergencyPeople

Sollicit Crisis Unit

Problems:

• Availability ofEmergency

People(Children Care,

distances,access,etc.)

• Weather =>PbRescuer access

1Hour

Send Second

Emergency

Postand

Materials

TASKS

Actor/UnitProblems

Figure 2: The responsible of emergency department tasks

and faced problems on a time line.

addition we represent the experiences; they help

representing several tasks and associated problems

as well as consequences of the non-respect by the

tasks of its attended duration and its

recommendations.

6 DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM

We develop several techniques in order to handle

problem solving and experience memorization. We

promote the use of experience feedback to support

learning and decision-making. As first solutions, we

offer to represent the experience feedback using on

one hand experience-based and situation

representation methods and on the other hand

knowledge engineering methods, in order to define

the specifications of a system as a decision making

support environment. We also aim at studying

scenario representation to promote learning from

this type of situations.

To guide decision makers in crisis situations we

can act at two levels. The first one concerns the

perception of the context as an important element in

reasoning process (Van der henst, 2002) by

providing additional and useful data with less

ambiguity about context using the quick and

automatic research in GIS system and situation

bases. The second one concern guiding the process

of decision making (Van der henst, 2002; Reed,

2011; Richard, 1998) as a cognitive process. We aim

at guiding the reasoning process during each phase

of the crisis using available cases in the situation

base.

Information processing in dynamic situations can

be distinguished by a number of dimensions from

decision making in the normally used static task

environments. First, because the environment

changes, time is an inherent dimension of the

decision making process. Second, strategies can be

used that benefit from feedback. Third, time pressure

can be defined from the evolving situation itself

rather than by some external criterion (Kerstholt,

1994).

Cognitive psychology is assumed to contribute

significantly to the improvement of analytical issues

and the quality of solutions offered in decision

support and problem solving. This could be achieved

by methods and tools for firstly making the analysis

of decision maker’s query; secondly, providing high

quality methodologies and systems evaluations. It

can thus define gaps to be narrowed. Finally, it

provides the knowledge and methods needed to

evaluate the proposed solutions.

Mental activities are a part of cognitive activities

(Van der henst, 2002; Reed, 2011; Richard, 1998).

They are located between sensorial and action

programming activities. It helps building an

understanding of the situation, developing new

knowledge and making decisions. Considering

information processing types, we can distinguish

three broad categories of mental activities (Reed,

2011): The understanding which consists in

constructing a situation interpretation, the reasoning

that is looking for links between information

collected via inferences using knowledge eventually

stored in the memory, then finally all the control

mechanisms of mental activity.

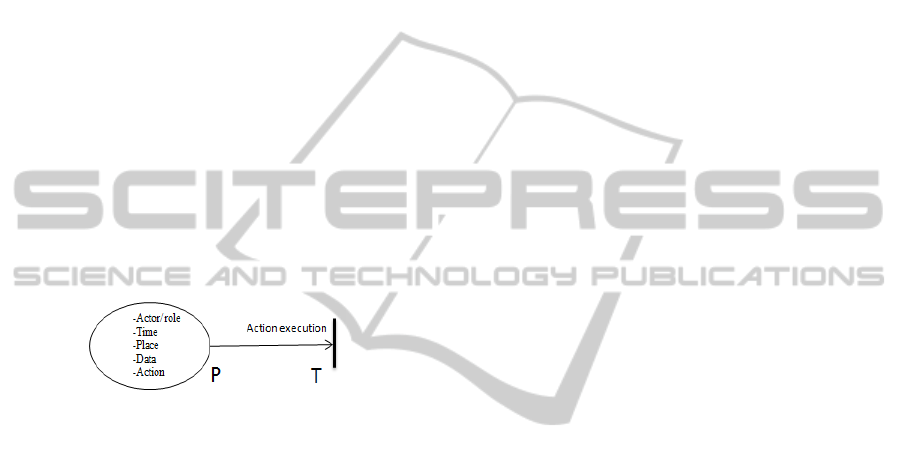

Figure 3: Petri network of crisis management -- P:

Actors/unit – T: event/tasks/exchanges (P0: the stable

system .-P1: Communication Center. -P2: Emergency

department.-P3: Intervention Teams. P4: hospitals. -P5:

Victims’ evacuation).

For better understanding of the intervention and

decision making steps, we may represent emergency

department crisis management as a set of couples of

states and events figure 3) using a basic Petri

network (Aich and Loriette, 2007). Each state of the

system match a crisis stage, it is represented by a

place of Petri network (figure 4):

DecisionSupportbyHandlingExperienceFeedbackofCrisisSituations

355

Type: It’s a sort of index referencing a complete or

episode of a crisis situation. It indicates the main

class (category) of current situation. (E.g. road-

accident, fire, etc). Providing this index help the

system to do research by keyword, it allows

recognition and rebuilding of such situation

through previous situations and keeping the link

with central event of crisis.

Actor/ role: is the concerned person or unit in each

system state (crisis stage).

Time: is the moment to do an action by the

concerned actor according to place’s type.

Data: is the available data for concerned actor in

each moment, this information are related to the

characteristics of crisis situations, localization,

weather and victims.

Action: is the action to execute considering

previous elements.

Place: is the actor location.

The event (transition) is defined as the result of

the action processing. It lends the next state the new

information.

Figure 4: Petri network’s State and transition of crisis

situation.

The starting point of our proposition is based on the

exchanges, the events and the tasks. All these

elements are important to determine the following

tasks to do or the decisions to make. Their definition

on situation structure (figure 1) helped us to identify

a set of system states, transitions and conditions

between them. Representation of these elements

inside the same structure for all actors is difficult.

Indeed. A concrete structure is relatively complex

considering the time and the space dimensions

(Figure 1 and Figure 2), it make its interpretation

difficult. While the transcription of a Petri network

allowed us to see these elements in the form of a

state / transition graph (figure 3) more simply and,

especially better defined. Transitions represent the

interactions between actors and events that can

change the system state and parts. The places (state)

represent the major interactions between the system

parts.

We use several techniques in order to identify a

representation structure of an accident. In fact,

works on situations representations give (Schreiber

et al., 1994) techniques to represent a situation as

states and events. CBR (Kolodner, 1993), (Burke et

al., 2000) proposes to define the context as well as

the solution of a problem. It also provides processes

for case retrieval and adaptation. Otherwise,

Knowledge engineering (Matta et al., 2002; Chebel

Moreloo, 2008; Cablé et al., 2011) techniques help

to extract and formalize expertise as strategies

(Dieng, 1998), plans, and concepts.

An efficient decision support environment has to

take into consideration the characteristics of crisis

situations (Turoff et al., 2004), the status of people

supposed using it and, space and time dimensions.

To sum up, firstly the provided information has to be

precise; the decision maker in crisis situation has no

tolerance or time to spend for things unrelated to the

management of crisis. Secondly, the context must be

understood and the experience reused; learning and

understanding what happened before, during, and

after the crisis is extremely important for the

improvement of the system capacities. Thirdly,

everything in a crisis is an exception, thus less

generalization is recommended. Finally, the

information exchange and its validity in timeliness is

required, in fact the crises require for many hundreds

of individuals with different roles to be able to

exchange information which is critical to those who

may risk lives and resources, these information must

the most up-to-date and notified by alerts.

The maps of emergency interventions represent

an essential tool; they show main information such

as the locations, the networks of streams and rivers,

and the locations of man-made features such as

trails, roads, towns, boundaries, and buildings. They

also show what the crisis site is like and distances

between useful crisis management stakeholders. All

of these are important considerations in emergency

planning. It make easier to decide where to go and

where to position things. Therefore, our system is

fitted with interactive maps allowing actors to zoom

to a custom scale for a detailed view of a specific

area of interest associated to several information.

These information concern essentially localization of

risk places, Human / materials resources,

emergency, rescuers means and services

information. So, we identified a number of risk

places and their characteristics in the AUBE’s State.

Further, used GIS should allow defending more

position and information on maps.

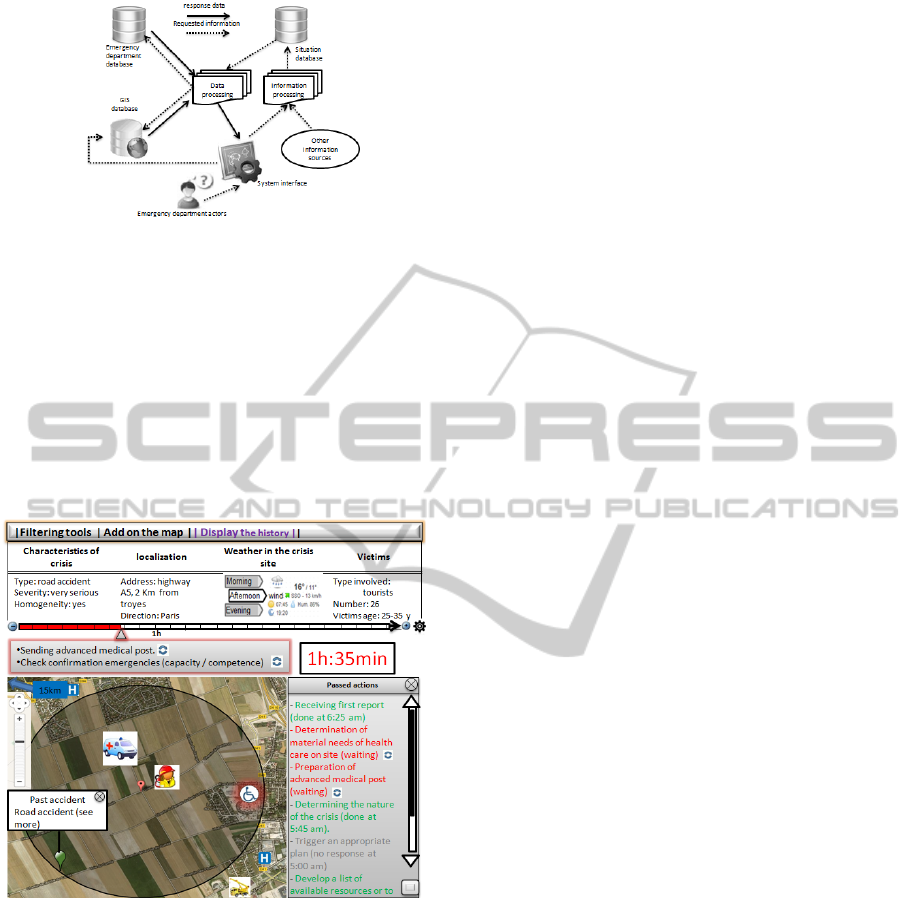

The environments integrate multiple data sources

(figure 5); the main one is our situation databases

which contextualize requested information. It allows

the data processing to use efficiently other data

sources.

The emergency department database contains

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

356

Figure 5: System data and information sources.

information about emergency department (human

resources, equipments, procedures, hospitals, etc).

The GIS database contains personalized

geographical information about risks and vulnerable

places and much other personalized information.

7 HUMAN MACHINE

INTERFACE

Figure 6: Emergency Responsible Interface Board.

We have proposed a human machine interface that

helps to handle the experience of emergency actors

(Sediri et al., 2013).

The main part of this interface is the map which

is an important tool for emergency department.

Several functionalities are offered by our

proposition, the top panel “Fig. 6” that help to

follow the evolution of the situations, the map and

top menu GIS that help to locate accident, around

risk sites, rescue materials resources, Hospitals, etc.,

a street view system that help to show the road

configuration, and a communication Interface that

help to send and collect information from and to

other actors. All these parts are interrelated (figure

5).

8 CONCLUSIONS

We show in this paper, our results on analyzing

crisis management. Our approach aims mainly at

identifying the experience feedback and representing

it (Sediri et al., 2013) the aim of this study is to

define a decision making environment for crisis

management, related to emergency activity. Future

work aim is to provide specification of the interface

of the system to promote decision support for each

role conceding the objectives of stakeholders in the

main project. Finally, we will focus on the definition

of experience traceability module for our system.

We use several approaches in order to represent this

experience:

We use GIS as base of the machine interface, it’s

the main part system for emergency department

that represent their experience feedback.

Crisis situations are a collaborative activity, so

organization, coordination and communication

dimensions have to be described.

Situations have to be represented in this

experience, so the dynamic dimension considering

events has to be defined. We use time thread,

which is an important aspect in crisis management

for this purpose.

Experience feedback has to be shown, so we use

knowledge engineering techniques (interviews

based on tasks, concepts and problem solving) in

order to represent at each step tasks, related

problems, success/fails keys, and related

consequences

Our purpose in the future work is to define the

model of the knowledge traceability. We aim also

with involved ergonomist analyzing the emergency

activity in order to define an adapted interface that

helps to use the emergency experience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank The Champagne-Ardennes Region and

FEDER, sponsors of this work.

REFERENCES

Aich, A., Loriette, S., 2007. Aided navigation for disabled

DecisionSupportbyHandlingExperienceFeedbackofCrisisSituations

357

people by re-use of experiments. Journal européen des

systèmes automatisés, 2007, vol.41, n° 2, p. 135-157.

Birregah, B., Muller, A., 2012. Interdependancy-based

approach of complex events in critical infrastructure

under crisis: A first step toward a global framework, in

proceedings of advances in safety, reliability and Risk

management, Berenguer Ch., Grall A., Gudes Soares

C. (Eds), Taylor 1 Francis Group, ISBN 978-0-415-

68379-1, London.

Burke, E. K., MacCarthy, B. L., Petrovic, S., 2000.

Structured cases in case-based reasoning – re-using

and adapting cases for time-tabling problems. Knowl.-

based Syst. 13 159-165.

Cablé, B., Nigro, J. M., Loriette, S., 2011. Scenario-based

anticipation for aided navigation. Fifth IEEE

International Conference on Research Challenges in

Information Science, 19-21 May 2011, Pointe-à-Pitre.

8 p.

Carver, L., Turoff, M., 2007. Human-Computer

Interaction: The Human and Computer as a Team in

Emergency Management Information Systems.

Communications of the ACM, vol. 50, no. 3, pages 33-

38.

Chakraborty, B., 2010. D. Ghosh, R. K. Maji., S. Garnaik,

N. Debnath. Knowledge Management with Case-

Based Reasoning Applied on Fire Emergency

Handling, Industrial Informatics (INDIN), 2010 8th

IEEE International Conference on, 708-713.

Chebel Moreloo, B., 2009. Retour et capitalisation

d’expérience, outils et démarches, Page 25. AFNOR,

2008.

Couty, E., 2004. Plan Blanc et gestion de crise, Guide

d’aide à l’élaboration des schémas départementaux et

des plans blancs des établissements de santé, La

république française ministère de la santé et de la

protection sociale.

Dieng, R., Corby, O., Giboin, A., Ribière, M., 1998.

Methods and Tools for Corporate Knowledge

Management, in Proc. of KAW'98, Banff, Canada.

French, S., Turoff, M., 2007. Decision Support Systems.

Communications of the ACM, vol. 50, Issue 3.

Hale, J., 1997. A Layered Communication Architecture

for the Support of Crisis Response. Journal of

Management Information Systems , vol. 14, issue 1,

pages 235-255.

Johnson, R., 2000. GIS Technology for Disasters and

Emergency Management, ESRI White Paper May

2000.

Kerstholt, J. H., 1994. Decision Making in a Dynamic

Situation: The Effect of Time Restrictions and

Uncertainty.

Kim, J. K., Sharman, R., Rao, H. R., Upadhyaya, S., 2007.

Efficiency of Critical Incident Management Systems:

Instrument Development and Validation. Decision

Support Systems, vol. 44, pages 235-250.

Kolodner, J., 1993. Case-based reasoning. Morgan

Kaufman Publishers Inc. San Francisco, CA, USA.

Isbn 1-55860-237-2.

Lagadec, P., 1993. Apprendre à gérer les crises. Paris :

Éditions d’Organisation.

Matta, N., Ermine, J. L., Aubertin, G., Trivin, J. Y., 2002.

Knowledge Capitalization with a knowledge

engineering approach: the MASK method, In

Knowledge Management and Organizational

Memories, Dieng-Kuntz R., Matta N. (Eds.), Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Matta, N., Loriette, S., Sediri, M., Nigro, J. M., Barloy, Y.,

Cahier, I. P., Hugerot, A., 2012. Crisis Management

experience based representation: Road accident

situations, In proceedings of IEEE, ACM, IFIP

International Conference on Collaboration

Technologies and Systems CTS 2012, Workshop

Knowledge Management and Collaboration, May,

Denver USA.

Moehrle. S., 2012. Generic self-learning decision support

system for large-scale disasters. Proceedings of the 9th

International ISCRAM Conference – Vancouver,

Canada, April.

Oomes, A. H. J., 2004. Organization awareness in crisis

management, Dynamic organigrams for more effective

disaster response. Proceedings ISCRAM 2004

Brussels, May 3-4.

Otim. S., 2006. A Case-Based Knowledge Management

System for Disaster Management: Fundamental

Concepts, Proceedings of the 3rd International

ISCRAM Conference (B. Van de Walle and M.

Turoff, eds.), Newark, NJ (USA).

Reed, K., 2011. Cognition, théorie et application. 3ème

édition Groupe De Boeck s.a., une traduction de la

8ème édition américaine par Etienne Verhasselt.

Richard, J. F., 1998. Les Activités mentales : comprendre,

raisonner, trouver des solutions. 3ème édition

ARMAND COLIN, paris 1990, 1998.

Schoenharl, T., Madey, G., Szab, G., Barabasi, A., 2006.

WIPER: A Multi-Agent System for Emergency

Response. 3rd International ISCRAM Conference

Newark, NJ (USA), May.

Schreiber, G., Wielinga, B., Van de Velde, W.,

Anjewierden, A., 1994. CML: The CommonKADS

Conceptual Modelling Language, Proceedings of

EKAW'94, Lecture Notes in AI N.867, L.Steels, G.

Schreiber, W.Van de Velde (Eds), Bonn:

SpringerVerlag, September, pp.1-25.

Sediri, M., Matta, N., Loriette, S., Hugerot, A., 2012. Vers

une représentation de situations de crise gérées par le

SAMU, Conférence IC, Juin, Paris.

Sediri, M., Matta, N., Loriette, S., Hugerot, A., 2013.

Crisis Clever, a System for Supporting Crisis

Managers, ISCRAM Conference Proceedings, 10th

International Conference on Information Systems for

Crisis Response and Management. Baden Baden,

Germany May.

Sediri, M.; Matta, N., Dai, J., Loriette, S., Hugerot, A.,

2013. Experience feedback guides for crisis

management using GIS. IEEE, ACM, IFIP

International Conference on Collaboration

Technologies and Systems CTS, Workshop

Knowledge Management and Collaboration.May, san

deigo USA.

Sell, C., Braun, I., 2009. Using a Workflow Management

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

358

System to Manage Emergency Plans. 6th International

ISCRAM Conference – Gothenburg, Sweden, May.

Shmidt, K., Simone, C., 1996. Coordination Mechanisms:

Towards a conceptual foundation for CSCW systems

design, Computer Supported Coorperative Work, The

journal of Collaborative Computing, Vol. 5.pp.155-

200.

Smith, D., Elliott, D., 2005. Key reading in crisis

management, System and structures for prevention and

recovery. Edited by Denis Smith and Dominic Elliott.

By Routledge.

Sommer, M., 2012. Learning decision Making: Some

ideas on how novices better can learn from skilled

response personnel, in Advances in safety, reliability

and Risk management, Berenguer Ch., Grall A.,

Gudes Soares C. (Eds), Taylor 1 Francis Group, ISBN

978-0-415-68379-1, London.

Turoff, M., Chumer, M., Van de Walle, B., Yao, X.,

2004.The Design of a Dynamic Emergency Response

Management Information System (DERMIS) Journal

of Information Technology Theory and Application,

pages 1-35.

Van der henst, J. P., 2002. Contexte et raisonnement

chapitre 9 de livre: le raisonnement humain, sous la

direction de Guy Politzer, p. 271-305. Traité des

sciences cognitives LAVOISIER.

Whybo, J. L., 2010. L’évaluation de la vulnérabilité à la

crise: le cas des préfectures en France, Télescope,

Vol.16, N°2.

DecisionSupportbyHandlingExperienceFeedbackofCrisisSituations

359