Designing Spoken Dialogue Systems based on Doctor-Patient

Conversation in the Diagnosis Process

Tesfa Tegegne and Theo van der Weide

Institute for Computing and Information Science, Science Faculty, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands

{tesfa, tvdw}@cs.ru.nl

Keywords:

Doctor-Patient Interaction, Culture, Spoken Dialogue System.

Abstract:

The paper describes the use of doctor-patient interaction in order to design a spoken dialogue system. In

this paper we analyze doctor and patient information seeking and information provision behavior. In our

experiments we found a difference in information seeking and information provisioning behavior of doctors

and patients, although statistically not significant. We identify some important roles that can be used as a

springboard to design a spoken dialogue system. Finally, we conclude that analyzing face-to-face doctor-

patient interaction can serve as an effective starting point to design spoken medical dialogues.

1 INTRODUCTION

Speech is one of the most effective means of commu-

nication for humans. It plays a great role especially

in man-machine interactions. Speech is natural and

the vast majority of humans are already fluent in us-

ing it for interpersonal communication. In the last two

decades there have been a lot of advances in the appli-

cation of spoken dialogue systems in different areas:

academia, military, and telecom companies. A dia-

logue system is one of the promising applications of

speech recognition and natural language processing.

Spoken language interaction with computers has be-

come a practical possibility both in scientific as well

as in commercial terms.

Spoken dialogue systems can be viewed as an

advanced application of spoken language technol-

ogy. Spoken dialogue systems provide an inter-

face between the user and a computer based ap-

plication that permits spoken interaction with the

application relatively in a natural manner (McTear,

2002). Fraser 1997, cited by (McTear, 2002), de-

fines spoken dialogue system as ”computer systems

with which humans interact on turn-by-turn basis and

in which spoken natural language plays an important

role in the communication”. Spoken dialogue sys-

tems enable semi-literate and illiterate users to inter-

act with a complex application in a natural way using

speech. Current spoken dialogue or/and IVR (Inter-

active Voice Response) systems restrict users in what

way they can say and how they can say it. However,

users of speech-based dialogue systems often do not

know exactly what information they require or how to

obtain it- they require the support of the dialogue sys-

tem to determine their precise requirement (a system

directed dialogue). For this reason, it is essential that

the spoken dialogue system is be able to engage users

in the dialogue rather than simply respond to prede-

termined spoken commands.

The propelling factor of this study is the adoption

and application of speech technology and its impact

on the healthcare sector in developing countries where

a significant number of the population is illiterate or

semi-literate. In this paper we analyze the doctor-

patient conversation in order to find out if we can

emulate the methods and techniques used in the con-

versation to design medical spoken dialogue system

that can be accessed easily by non-educated or semi-

educated population with the objective of searching

health information remotely.

Nowadays, mobile becomes an appropriate

medium to minimize the burden of healthcare in de-

veloping countries. Several researchers, for exam-

ple (Black et al., 2009; Bickmore and Giorgino, 2006;

Foster, 2011), are engaged in mobile based applica-

tions such as mHealth, mLearning, mBanking, mA-

griculture etc. The expansion of the mobile network

and the increment of mobile phone users in Ethiopia

provide a fertile ground to adopt and implement mo-

bile based healthcare applications. Designing a med-

ical dialogue alike doctor-patient interaction is very

cumbersome, the advancement of speech recogni-

tion requires another level to fully understand human

speech. It requires at least to design and develop a

261

Tegegne T. and van der Weide T.

Designing Spoken Dialogue Systems based on Doctor-Patient Conversation in the Diagnosis Process.

DOI: 10.5220/0004776302610268

In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2013), pages 261-268

ISBN: 978-989-8565-56-3

Copyright

c

2013 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

medical dialogue system resembling human-like con-

versation to reduce the error of speech recognition.

Our main motivation is to understand whether face-

to-face doctor-patient interaction plays a vital role in

designing human-like medical spoken dialogue sys-

tem for the healthcare domain in the case of Ethiopia

using Amharic language. To the best of our knowl-

edge this is the first study that not only analyzes the

doctor-patient conversation but also designs and mod-

els a medical dialogue system in the case of Ethiopia.

In this paper we address the following question: Is

it possible to design a spoken medical dialogue sys-

tem based on doctor-patient face-to-face conversation

in the diagnosis process? The paper is organized as

follows. The state of the art of medical dialogue sys-

tems is discussed in section 2. The analysis of the ex-

periment is presented in section 3. Section 4 explains

the proposed spoken dialogue system. Finally, section

5 concludes the paper and gives future directions.

2 SPOKEN DIALOGUE SYSTEMS

IN HEALTHCARE

The healthcare domain has gleaned the benefits of the

advancements of Information Communication Tech-

nology. During the last two decades, these interfaces

have been adopted as part of tele-medicine technolo-

gies (Bickmore et al., 2006; Bickmore and Giorgino,

2006), which enable the delivery of a variety of med-

ical services to sites that are at a long distance from

providers.

The ultimate goal of a dialogue system is to pro-

vide health information for stakeholders primarily us-

ing spoken dialogue. Such a system can be used

for a wide range of applications including: patients

self-treatment and management, disease remote mon-

itoring, diagnosis, health education etc. In line to

this Bickmore and Giorgino ((Bickmore et al., 2006))

say that automated dialogue systems are increas-

ingly being used in healthcare to provide informa-

tion, advice, counseling, disease monitoring, clinical

problem identification, as well as enhancing patient-

provider communication.

However, a dialogue system in the healthcare do-

main is not without challenges. Clinical practice or-

dains complicated guidelines, ontologies and proce-

dures. This makes the dialogue system more com-

plex and cumbersome to handle. Bickmore and

Giorgino also mention some of the challenges of spo-

ken medical dialogue system: criticality (emergency

cases), confidentiality (privacy such as HIV/AIDS

regimen etc.) and mixed initiatives (patient-centered

vs. system-centered). They point out that incorpo-

rating medical and behavioral ontologies and deep

knowledge of health communication strategies are

very important for further development of medical di-

alogue systems.

Bickmore and Giorgino argue that face-to-face

communication together with written instructions re-

mains one of the best methods for communicating

health information to patients with low literacy level.

They report that face-to-face consultation is effective

because providers can use verbal and nonverbal be-

havior, such as head nods, hand gesture, eye gaze

cues and facial displays to communicate factual in-

formation to patients, as well as to communicate em-

pathy and immediacy to elicit patient trust. Accord-

ing to Durling and Lumsden ((Durling and Lumsden,

2008)) a spoken dialogue takes half the time needed

to achieve the same task using keyboard and mouse,

regardless of the participant’s ability to correct their

input. By highlighting the business side of speech

recognition in healthcare, Parente et al., cited by Durl-

ing and Lumsden, show that, in their opinion, the

adoption of speech technology is worthwhile. The use

of speech recognition has, in fact, seen the most suc-

cessful adoption in the healthcare domain.

2.1 Diagnosis Systems

Diagnosis, according to Webster’s dictionary,is the

act or process of deciding the nature of disease or

a problem by examining symptoms. In the medical

domain, many diagnosis systems are proposed and

used such as decision support systems, agent based

systems, and intelligent systems (fuzzy logic, expert

system, neural networks and the like). Mobile diag-

nostic technology is a relatively new concept in tele-

medicine. As suggested by the term itself, it involves

two key characteristics: mobility and remote diagno-

sis (Celi et al., 2009). The aim of using mobile tech-

nologies for healthcare is to support the patients out-

side of the medical and/or home environment.

2.2 Doctor-Patient Face-to-Face

Interaction

The main goal of a doctor-patient conversation is a

focused gathering with a common goal pursued by

its participants. Typically, a patient visits a doctor

with the purpose to be relieved from feeling unwell

possibly caused by an illness; the doctor’s purpose

of the interaction with the patient also is to relieve

the patient. When both parties appear to fail to com-

prehend or understand each other’s goal, the interac-

tion may be dysfunctional. Studying and analyzing

the doctor-patient interaction helps to convey empa-

Third International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

262

thy and obtain a trusted spoken dialogue system, es-

pecially when used by the semi-literate and illiterate

rural people. The analysis should help to design a

full-fledged medical dialogue system. As we pointed

out in the previous sections, the main idea here is not

to analyze the effectiveness and efficiency of the face-

to-face doctor-patient interaction but rather the impli-

cations towards designing and modeling ’human-like’

medical dialogue system.

A good interaction and a quality relationship be-

tween doctors and their patients is now widely rec-

ognized as a key factor in improving not only patient

satisfaction but also treatment outcomes across a wide

range of healthcare disciplines. The use of specific

doctor communication skills has been associated with

improved adherence regimens, improved psycholog-

ical outcomes, more detailed medical histories and

fewer malpractice suits, in addition to increase patient

satisfaction (Bickmore et al., 2005). Doctor’s listen-

ing behavior is a necessary ingredient for an interac-

tion in which patients are describing and expressing

themselves freely and openly (Nevile, 2006).

To test the doctor’s listening behavior, the rela-

tive frequency of each category of information seek-

ing and information giving behavior is calculated for

the doctor-patient interactions, representing the num-

ber of dialogue acts in any particular category as a

proportion of the total number of dialogue acts made

by the speaker. A relative frequency of medical topics

addressed in every interaction is calculated for all in-

teractions. The doctor as a facilitator of doctor-patient

interaction should demonstrate a high frequency of

supportive and encouraging behavior in the presence

or absence of patient desired behavior. Even though

a patient’s characteristics are very important to the

quality of interaction, the doctor’s facilitating behav-

ior is essential since it allows patients either to express

themselves or to repress (Nevile, 2006).

3 FINDING CULTURAL

DEPENDENCIES

Information seeking behavior includes seeking infor-

mation about medical topics. Direct, assertive and

embedded question types are posed by both parties.

On the other hand, information provisioning or in-

formation giving is providing a direct answer to a

question, elaborating the question by providing sup-

plementary information and deviating or changing the

topics of the interaction without prompting from the

interacting partner.

In this study we group the doctor-patient conver-

sation into two categories: information seeking be-

havior and information provisioning behavior. Infor-

mation seeking consists of utterances about informa-

tion gathering, checking and cueing. Information pro-

visioning contains utterances dealing with explana-

tion, confirmation, and giving instructions. Both in-

formation seeking and information provisioning are

analyzed against medical topics: illness, symptoms,

diagnosis, treatment, exam/test and history (medical

history) for both doctor and patient.

In the analysis we remove backchannels.

Backchannels contain, greetings, and acknowledg-

ment that carry little information value for healthcare

doctors and patients. Removing backchannels should

not affect the quality of information obtained from

the interaction. We use a two-way ANOVA (Analysis

of Variance) to see the difference between doctor

and patient in the two criteria and medical topics

or themes. Additionally, we check the number of

questions posed by doctors and patients. Finally, we

analyze the overall interaction process.

3.1 Methodology

The focus of this research is to design a spoken med-

ical dialogue system on the basis of doctor-patient

face-to-face interactions, to understand the weak and

strong side of the interaction and to utilize actions

taken place during the interaction. We have con-

ducted a number of observational studies in which we

recorded the interaction between patients and health

professionals. Based on these observations we de-

sign the content of the conversation including ques-

tion and declarative statements, the order of presen-

tation of content, how a system responds to ques-

tions and words, sentence structure and tone used, to

closely match the user expectations of what a health

professional might ask, respond and sound like. In-

depth interview studies show that this is perceived by

patients as a successful conversation (Migneault et al.,

2006).

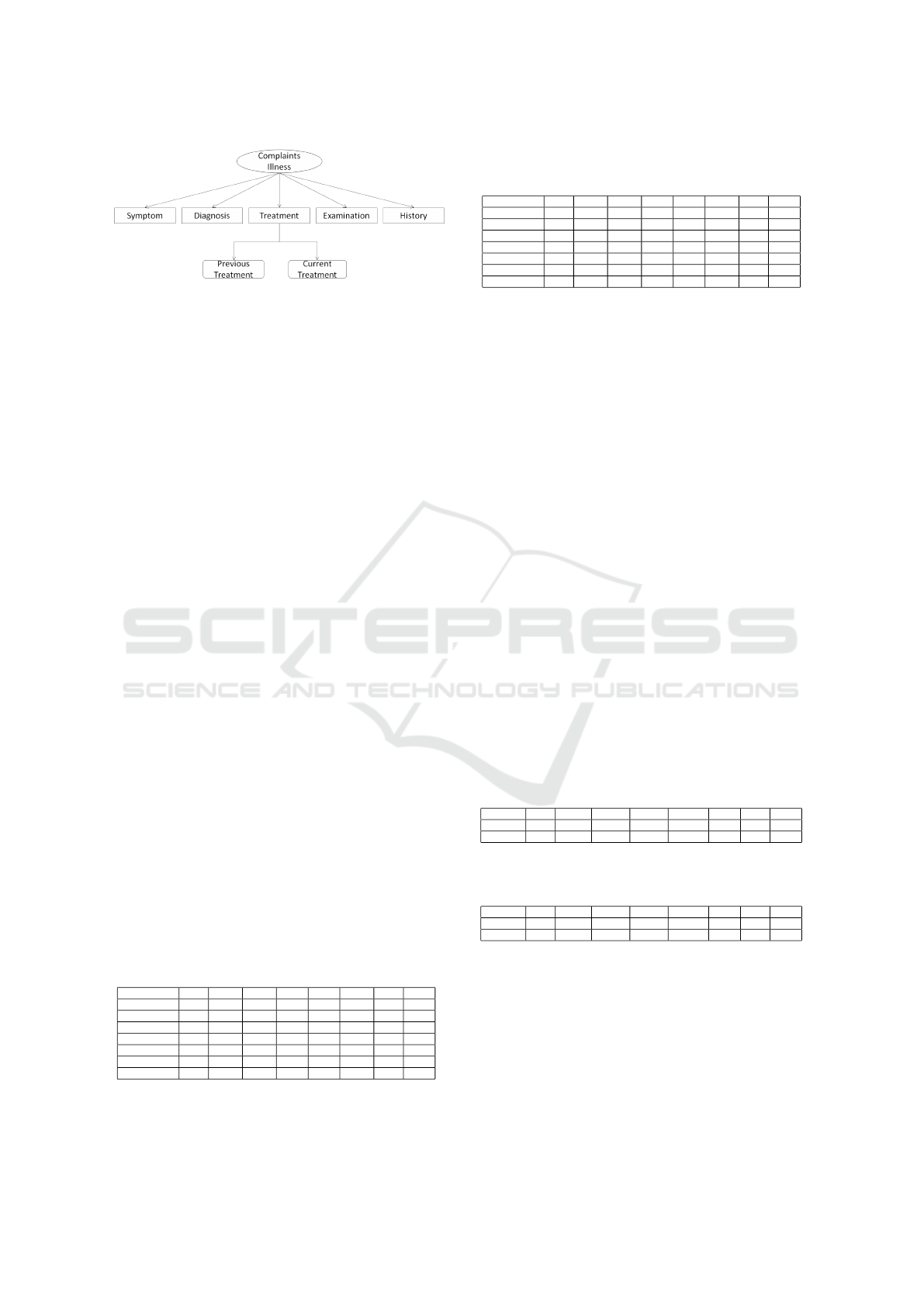

The doctor-patient interactions are analyzed as

follows. We classify the elicitation process based on

semantic entities as shown in figure 1, leading to the

following topics: (i) Illness, (ii) Symptoms, (iii) Di-

agnosis, (iv) Previous Treatment, (v) Current Treat-

ment and (vi) Exam. Questions and Explanations

are targeted towards the following variables proposed

by (Nowak, 2011): (i) information, (ii) confirmation,

(iii) checking, (iv) explanation, (v) cue and (vi) giving

instruction.

First we address the efforts taken by both doc-

tor and patient to identify problems and attempting

to recommend. This includes the process of elicita-

tion (information gathering), explanation, confirma-

Designing Spoken Dialogue Systems based on Doctor-Patient Conversation in the Diagnosis Process

263

Figure 1: Semantic Entities of Doctor-patient conversation.

tion, checking, cue and giving instruction. We tran-

scribed the audio recordings manually and tabulating

into three categories: Information elicitation or infor-

mation seeking and information provisioning or (in-

formation giving) in the case of the doctor and the

patient in the interaction. We analyzed 29 conversa-

tions done by 4 doctors and 29 patients among 50

patients. We chose only patients coming for diag-

nostic purposes and ignored follow-up patients since

it doesn’t include the elicitation criteria (information

gathering/seeking and information provisioning) and

medical topics (illness, symptoms, diagnosis, treat-

ment, exam/test and history) for diagnostic purpose.

3.2 Results

We have collected data to find out how, in the

Ethiopian context, patients elicit information during

a doctor-patient conversation. Therefore we have

audio-taped 50 real doctor-patient interactions. The

conversations took 6-7 minutes on average. The sta-

tistical analysis of the face-to-face doctor-patient in-

teraction has resulted in the following findings. Out

of 29 medical interactions, comprising of 442 turns,

171 (38%) turns classified as Information gathering,

167 (38%) utterances are uttered by doctors to elicit

health information and only 4 (1%) of the utterances

are uttered by the patients. Table 1 shows the break-

down of the doctor contributions to the doctor-patient

interactions into (variable, topic) combinations. Table

2 shows this breakdown for the patient contributions.

We may interpret this table as an estimator for prob-

abilities as Prob (v—t, a) for variable v, topic t and

actor a (either doctor or patient).

Table 1: Doctor utterances in medical information elicita-

tion process in face-to-face interaction.

Illn Smpt Diag P.Tr C.Tr Exam Hist Total

Information 34 110 9 5 0 1 8 167

Confirmation 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 2

Checking 1 5 9 8 1 4 1 29

Explanation 6 4 9 3 1 5 0 28

Cue 2 1 2 0 1 0 1 7

Instruction 0 0 3 1 0 5 2 11

Total 43 122 32 17 3 15 12 244

Our first conclusion is that the interaction is

mainly led by the doctor. The first dialogue act is a

Table 2: Patient utterances in medical information request

in the face-to-face diagnosis processes.

Illn Smpt Diag P.Tr C.Tr Exam Hist Total

Information 1 2 0 0 0 1 0 4

Confirmation 6 36 1 4 2 2 1 52

Checking 0 28 2 2 0 0 2 34

Explanation 12 76 5 6 0 1 3 103

Cue 0 0 4 1 0 0 0 5

Instruction 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 10

Total 19 142 12 13 2 4 6 198

question posed by the doctor like ’How are you feel-

ing?’. Then the patient explains complaints or feel-

ings (s)he has. The doctor then will ask additional

questions to identify causes, symptoms, and illnesses.

Table 3 and 4 show information seeking and in-

formation provision of doctors and patients. We see

that information seeking behavior of doctors (46%)

is higher than that of patients (10%). Whereas, pa-

tients’ information provisioning behavior (35%) is

much higher than doctors’ (9%). Besides, symp-

toms 60%, illness 14%, diagnosis 10%, treatment 8%,

exam test and history 4% are addressed. In these

doctor-patient interactions the medical topic has been

given much attention during information seeking and

information provision (about 122 turns used by the

doctor for information seeking and 142 turns by pa-

tients to reply the questions posed by the doctor about

the symptoms). The most prominent divergence ap-

pears in the fact that doctors most frequently initiated

questions targeted towards information (68%), much

less frequently towards checking (12%), and even less

frequently towards explanation (11%), giving instruc-

tion (5%), cue (3%) and conformation (1%). The pa-

tients merely were answering the questions posed by

the doctor.

Table 3: Information seeking and information provision be-

havior of Patient.

Illn Smpt Diag P.Tr C.Tr Exam Hist Total

InfoSeek 1 30 2 2 0 1 2 38

InfoProv 18 112 10 11 2 3 4 160

Table 4: Information seeking and information provision be-

havior of doctor.

Illn Smpt Diag P.Tr C.Tr Exam Hist Total

InfoSeek 35 115 21 14 1 10 11 207

InfoProv 8 7 11 3 2 5 1 37

3.3 Discussion

As discussed in the preceding section, turn taking is a

dialogue act. A turn is defined as speaking without in-

terruption. From the doctor-patient audio recordings

we found that the number of turns of doctors is 276

and 238 of the patients. This figure indicates that the

doctor speaks in long turns 56% over patients 46%.

In general, patients talk less than doctors and most

Third International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

264

of their interaction is in the form of giving informa-

tion in response to doctor questions. Many studies in-

dicate that doctor’s dialogue acts encourage patients

to discuss their opinions, express feelings, ask ques-

tions, and participate in decision making. This helps

the doctor to more accurately understand the patient’s

goals, interests, and concerns as well allows the doc-

tors to better align his conversation/interaction with

the patient’s agenda (Goold and Lipkin, 1999; Ver-

linde et al., 2012). On the contrary, some studies re-

port that doctors often underestimate patients’ desire

for information, while overestimating their medical

knowledge (Bickmore et al., 2006). Thus, allowing

patients to ask questions, express concerns and state

preference helps the doctor to infer matters that are

important to patients in relation to their compliance.

Our findings show that the dialogue is initiated

by the doctor in order to seek information about the

patients health compliance and illnesses. Moreover,

the dialogue is controlled by doctors to gather addi-

tional information about the illness (such as symp-

toms, illness history and medication). Generally, the

request for information sets the initial purpose or goal

that motivates the speaker’s actions for the remain-

ing section of the dialogue. The request for informa-

tion further specified by one or more discourse seg-

ments. Asking questions and providing answers play

a significant role in the process of the medical con-

sultation. Mainly, the aim of doctor-centered behav-

ior is efficiently gathering sufficient information to

make a diagnosis and consider treatment options in

the least amount of time necessary. This is in con-

trast to patient-centered interactions that can recog-

nize patients as collaborators who can share not only

their biomedical states (physical condition and well

being) but also knowledge of their psychological sit-

uations (personality, culture, social relations, etc.).

The result of quantitative analysis shows, there still

is an equal distribution of information seeking (ques-

tions) between the dialogue participants, with almost

all elicitation initiated on the part of the doctor. The

data also demonstrate that both doctors and patients

emphasize on asking and responding about symptoms

and illnesses. For example from a total of 442 dia-

logue acts, 122 and 142 dialogue acts are used to elicit

symptom information by doctors and patients. Gener-

ally, 59.7% of the interaction was devoted to seeking

and giving information about symptoms and 14% of

illnesses. The finding show a significant difference

(F= 14.02, P=0.0026, alpha= 0.05 ) between doctors’

and patients’ information seeking behavior in f-test,

but no significance difference is found in patients’ and

doctors’ information giving behavior.

We also analyzed the data using two-way analysis

of variance. We found that the information seeking

score of doctors is higher than for patients, but the

difference is statistically not significant. The score

of information giving behavior of patients was higher

than the doctors, but similarly there is no significant

difference. The first impression about people often

turns into long-term perceptions and reputations. So

doctors in their first encounter should make good eye

contact, shake patient’s hand and introduce himself.

In the face-to-face interaction we recorded that there

were no greetings and introduction during the initial

doctor-patient interaction. In each dialogue sentence

or clauses the participant (doctor/patient) utterance is

categorized into semantic entities (figure 1) in which

the dialogue theme is emphasized. Since the conver-

sation is between a doctor and patient for diagnosis

purpose we identify the main concepts evolved in the

interaction process. Compliant, symptoms, treatment,

illness, exams, history, and prescription are the most

common entities used in the doctor-patient conversa-

tion.

3.4 Cultural Aspects

Cultural differences may be an obstruction for ef-

fective doctor-patient interaction. The cultural per-

ceptions of health, sickness, and medical care of pa-

tients and families may differ with that of the doc-

tors. Speaking the same language and being born in

the same location does not automatically mean shar-

ing all the elements of a particular culture. Studies

have shown that a patient’s culture will affect the way

they perceive their body, illness, and disease. This

is also true for the doctors as their own families and

communities have also helped to shape these cultural

beliefs within them. Each participant in the medical

interview brings with them the culture in which they

were raised. At times, differing cultural beliefs can

have an adverse effect on the care that one receives.

Communication problems arise when the patient and

doctor do not share the same culture.

Culture competencies in medical interaction pro-

vide a patient centered care by adjusting their atti-

tudes and behaviors to the needs and desires of differ-

ent patients and account for emotional, cultural, so-

cial, and psychosocial issues on disease and illness.

Medical competencies relate directly with the doctor-

patient interaction that are required by the doctors to

conduct an effective interview and to create an accept-

able plan of diagnosis and treatment. Studies indicate

that issues that may cause problems in cross-cultural

encounters are authority, physical contact, communi-

cation styles, gender, sexuality, and family.

Hofstede (Hofstede et al., 2010) has identified five

Designing Spoken Dialogue Systems based on Doctor-Patient Conversation in the Diagnosis Process

265

cultural dimensions. (1) Power Distance focuses on

the perceived degree of equality, or inequality. Ac-

cording to Hofstede et al., [2010] ”A high power dis-

tance ranking indicates that inequalities of power and

wealth have been allowed to grow with the society. In

these societies equality and opportunity for everyone

is stressed”. In large power distance cultures, ones

social status must be clear so that others can show

proper respect. In line with this, Hofstede et al. as-

sert that the power distance exhibited in society also

is reflected in the relationship of doctors and patients.

They say that ”in countries with large-power distance

cultures, consultations take less time, and there is less

room for unexpected information exchanges”. The

findings indicate that the average time spent on face-

to-face consultation is 4-6 minutes. This result con-

firms that power distance plays a major role in doctor-

patient interaction. According to Hofstede, Ethiopia

is a large power distance country, so the interaction is

dominated by doctors and patients rarely participated

in treatment and diagnosis decision makings.This is

true especially for illiterate and rural people. The

power distance of literate people and doctors is bet-

ter compared to the illiterate. In line with this (Ver-

linde et al., 2012) said that doctors asked less edu-

cated patients and low income patients more ques-

tions about their disease and medical history. Like-

wise, our findings indicate that doctors’ information

seeking behavior is more than that of patients’. Gen-

erally, in Ethiopia, patients treat doctors as superiors,

consultations are shorter and controlled by doctors.

(2) Hofstede’s cultural dimension indicates that

Ethiopia as a low individualism country. The im-

plication of individualism in healthcare particularly

in doctor-patient interaction goes with patient auton-

omy, the possibility of choice, flexibility of social

roles, less conformity, and psychosocial information

exchange (Meeuwesen et al., 2009)

(3) Ethiopia is a masculine country (Hofstede’s cul-

tural dimension); however, regardless of other dimen-

sions, masculinity doesn’t reflect on the patient - doc-

tor interaction in diagnosis and treatment. Some stud-

ies revealed that there is a difference between female

and male doctors in creating partnerships, with pa-

tients and dealing with psychosocial issues during the

conversation. Meeuwesen et al., [2009] stated that

the more masculine a county, the more instrumen-

tal (disease centered) interaction will dominate, the

less attention will be paid for psychosocial issues and

more frequently the majority of doctors will be men or

male. The analysis result shows that mainly the inter-

action between doctors and patients was on the theme

of symptoms 60% and illnesses 14%. Eventually the

theme of the conversation is disease-centered.

(4) Uncertainty Avoidance in the healthcare domain

primarily deals with patients’ emotionality or anx-

iety, or stress and doctor’s task-orientation, prefer-

ences of technological solution and degree of med-

ication. In countries with strong uncertainty avoid-

ance (Meeuwesen et al., 2009) the more disease-

centered (instrumental talking), the less affective talk-

ing and the more biomedical exchange can be ex-

pected. This a true scenario in Ethiopia cases; since

doctors indulge themselves in diagnosing the illness.

In the experiment, we have not found a single in-

troduction (greetings) communication act. Hofstede

further explained that ”doctors in uncertainty tolerant

countries more often send patients away with com-

forting talk, without any prescription. In uncertainty

avoiding countries doctors usually prescribe several

drugs, and patients expect them to do so” (Hofstede

et al., 2010).

(5) Regarding long-term orientation, as Ethiopia

doesn’t have data we left out in our analysis.

4 A SPOKEN DIALOGUE MODEL

Eliciting user requests in the medical spoken dia-

logue is the main challenge for developers and imple-

menters of the system. Unlike a face-to-face doctor-

patient interaction it is very hard to analyze the pa-

tients’ attitudes and emotions. As a result the eliciting

techniques should be patient centered; and the main

role of the doctor is a facilitating behavior, focused

and unfocused open questioning, request for clarifi-

cation, summarizing and empathy. Thus, the dialogue

system should act like human which can help to elicit

the patients’ request in order to provide accurate con-

sultation, diagnosis and treatment.

To the best of our knowledge eliciting user medi-

cal requests using spoken medical dialogue based on

some suggested principles is not assessed, and there

is no any results obtained. Our objective is using

the best practice of in-person doctor-patient interac-

tion activities to be adopted in the spoken medical

dialogue system to search medical information using

mobile phones.

4.1 A Simplified Dialogue System

Spoken medical dialogue tends to be patient centered.

Thus the system should facilitate the interaction and

ask open questions in which the patients can express

not only knowledge of their biomedical state (illness

and complaints) but also knowledge of their psycho-

logical and social situations (personality, culture, re-

lationships). As discussed before, the face-to-face in-

Third International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

266

teraction in Ethiopia is doctor dominated. However,

in the dialogue system it is impossible to detect the

non-verbal behavior of the patient. Thus, the elicita-

tion should be dominated by the patient in order to

seek biomedical as well as psychosocial situations of

the patient. Doctor’s behavior that encourages patient

active participation includes asking open ended ques-

tions, ensuring and confirming patient comprehen-

sion, requesting patients’ opinions, and making state-

ments of concern, agreement and approval. Hence,

spoken dialogue to resemble human-human interac-

tion, should encourage patients to take part actively

in the interaction process. Instead of being expecting

responses from patients, the system must take a fa-

cilitative role in order to provide time and space for

patients to speak out what their symptoms, illnesses,

suggestions and to participate in decision making.

From the analysis of the in-person interaction of

doctors and patients, it was found that there are some

gaps that should be filled. The main gaps observed

in the face-to-face interaction is doctor domination as

well as we identified that the social status of patients

and doctors inhibits the interaction process. Other

factors that affect the face to face interaction are il-

literacy and culture. In rural Ethiopia, the illiteracy

rate is higher than in urban areas, so patients from

rural areas visited find the interaction with the doc-

tor is difficult; the doctor may consider that non ed-

ucated rural patients do not express themselves so

that a doctor prefers to ask some closed questions and

open leading questions to elicit the user requirements.

But even when doctors and patients born and live in

the same area, they do not necessarily have the same

understanding of social norms and cultures. Conse-

quently, the non-literate rural patients are more con-

servative of their values and cultures; some of the ill-

ness may not be disclosed in public so to keep their

culture or values they reserved from disclosing their

feelings, symptoms and illnesses. For instance, a

study conducted in USA revealed the gap between

doctors and Ethiopian migrants in disclosing illnesses

and diseases. According to this study, the migrants

did not want to be told if their disease is life threat-

ening; whereas, doctors in US disclose the nature of

the illness, the risks of the illness (curable and incur-

able) and the magnitude of the illness (treatable or

non-treatable) (Beyene, 1992).

From the face-to-face doctor-patient interaction

we deduce the user request elicitation model dis-

played in figure 2 for spoken dialogue system for

healthcare application. The model consists of four

components: opening initiatives, asking information,

giving information and closing. Figure 2 displays user

request elicitation process for the spoken dialogue

systems in a healthcare scenario based on doctor-

patient face-to-face dialogue.

4.2 Design Dialogue System

Data validity, accuracy and integrity are the vital

points to be considered in designing a spoken dia-

logue application; since automatic speech recogni-

tion(ASR) technology is not perfect. The design

of spoken dialogue technology should take into ac-

count the possibility of speech recognition errors and

improve the overall accuracy using dialogue actions

such as re-prompts, conformations, error correction

and handling etc. Secondly, it should provide equal

access to novice and experienced end users of the

system. Thirdly, it should also consider individual

differences such as personalization and user context.

Finally, before developing the dialogue system it is

very important to conduct a face-to-face interview or

pay live observation while a doctor is treating a pa-

tient (if possible video tape the conversations). The

most commonly applied methods to design a spoken

dialogue include human-human dialogues and design

by simulation. Thus, our interest lies on to look into

doctor-patient interactions as a means to design med-

ical spoken dialogue.

Figure 2: User request elicitation process.

4.3 Designing a Dialogue based on

Doctor-Patient Interaction

Human-human dialogue provides an insight how hu-

mans accomplish a task-oriented dialogue. The

doctor-patent interaction studies take place in the

early stages of the speech application life cycle. They

act as a starting point for spoken dialogue design and

help to define requirements. The purposes of doctor-

patient interaction studies are to help the designer see

the task form the user point of view, develop a feeling

for the style of interaction, and acquire some specific

knowledge about the vocabulary and grammar used in

the diagnostic process.

Designing Spoken Dialogue Systems based on Doctor-Patient Conversation in the Diagnosis Process

267

Doctor-patient interaction (natural dialogue) study

differs significantly from the wizard-of-oz studies,

that have been used extensively by others in the design

of spoken dialogue systems. Researchers who use the

wizard-of-oz techniques begin the process with a pre-

experimental phase that involves studying natural hu-

man dialogues. Whereas the natural dialogue takes

place prior to any system design or functional specifi-

cations (Yankelovich, 2008). The main purpose is to

launch the design process.

Before designing the medical dialogue system, we

wanted to discover how doctors and patients inter-

act in the diagnosis process. From the analysis of

the doctor-patient interaction, we found that the in-

teraction is doctor-centered as well as we found that

patients question asking behavior is hampered by the

cultural influences such as: distance power, high un-

certainty avoidance and the like (see section 3.5).

It is impossible to produce a medical dialogue sys-

tem design based entirely on doctor-patient face-to-

face interaction. Rather it can play an important role

in the early stages of the development life cycle, and

serve as an effective starting point for spoken medical

dialogue system design.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have analyzed the interaction in 29 audio-taped

doctor-patient diagnosis dialogues in the Gamby

Teaching hospital. The study is mainly conducted

to investigate the information seeking and informa-

tion provisioning behavior of doctors and patients.

The finding shows that there is no statistical signif-

icant difference between doctor information seeking

and patient information seeking behavior. Similarly,

we didn’t find any significant difference between pa-

tients information provisioning and doctors informa-

tion provisioning behavior. From this analysis we

conclude that studying face-to-face interaction be-

tween doctor and patients is an effective starting point

for spoken medical dialogue system design. We also

found an influence of culture on doctor-patient in-

teraction; so cultural values should be incorporated

while designing and developing a medical dialogue

system. Finally, based on our results, we propose a

model to assist user requirements elicitation in order

to develop a medical spoken dialogue system. In the

future we will implement our model to develop a med-

ical dialogue system.

REFERENCES

Beyene, Y. (1992). Medical disclosure and refugees - telling

bad news to ethiopian patients,. The Western Journal

of Medicine, 157(3):328 332.

Bickmore, T. and Giorgino, T. (2006). Methodological

review: Health dialog systems for patients and con-

sumers. Biomedical Informatics, 39(5):556–571.

Bickmore, T., Giorgino, T., Green, N., and Picard, R.

(2006). Special issue on dialog systems for health

communication. Biomedical Informatics, 39(5).

Bickmore, T., Gruber, A., and Picard, R. (2005). Estab-

lishing the computer-patient working alliance in auto-

mated health behavior change interventions. Patient

Educ Couns., 59(1):21–30.

Black, J., Koch, F., Sonenberg, L.and Scheepers, R., Kahan-

doker, A., Charry, E., Walker, B., and Soe, L. (2009).

Mobile solutions for front-line health workers in de-

veloping countries. In Healthcom, pages 89–93.

Celi, L., Sarmenta, L., Rotberg, J., Marcelo, A., and Clif-

ford, G. (2009). Mobile care (moca) for remote diag-

nosis and screening. Journal for Health Informatics

in Developing Countries, 3(1):17–21.

Durling, S. and Lumsden, J. (2008). Speech recognition use

in healthcare applications. In MoMM 2008.

Foster, C. (2011). Icts and informal learning in developing

countries.

Goold, S. and Lipkin, M. (1999). The doctor patient re-

lationship challenges, opportunities, and strategies. J

Gen Intern Med., 14(Supp1):26–33.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G., and Minkov, M. (2010). Cul-

tures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: In-

tercultureal Cooperation and Its Importance for Sur-

vival. McGraw Hill.

McTear, M. (2002). Spoken dialogue technology: Enabling

the conversational user interface. ACM Computing

Survey, 34(1).

Meeuwesen, L., van den Brink-Muinen, A., and G., H.

(2009). Can dimensions of national culture predict

cross-national differences in medical communication?

Patient Education and Counsiling, 75:58–66.

Migneault, J., Farzanfar, R., Wright, J., and Friedman, R.

(2006). How to write health dialog for a talking com-

puter. Biomedical Informatics, 39:468–481.

Nevile, M. (2006). Communication in context: A conver-

sation analysis tool for examining recorded voice data

in investigations of aviation occurrences. Technical

report.

Nowak, P. (2011). Synthesis of qualitative linguistic re-

searcha pilot review integrating and generalizing find-

ings on doctorpatient interaction. Patient Education

and Counseling, 82(3):429–441.

Verlinde, E., De Laender, N., De Maesschalck, S., De-

veugele, M., and Willems, S. (2012). The social gra-

dient in doctor-patient communication. International

Journal for Equity in Health, 11(12).

Yankelovich, N. (2008). Using natural dialogs as the basis

for speech interface design. Human Factors and Voice

Interactive Systems Signals and Communication Tech-

nology, pages 255–290.

Third International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

268