Importance of Considering User’s Social Skills in Human-agent

Interactions

Is Performing Self-adaptors Appropriate for Virtual Agents?

Tomoko Koda and Hiroshi Higashino

Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, Osaka Institute of Technology, Osaka, Japan

Keywords: Conversational Agents, Gesture, Self-adaptors, Non-verbal Behaviour, Social Skills, Evaluation.

Abstract: Self-adaptors are bodily behaviours that often involve self-touch that is regarded as taboo in public.

However, self-adaptors also occur during casual conversations between friends. We developed a virtual

agent that exhibits self-adaptors during conversation with users. Our continuous evaluation of the

interaction between the agents that exhibit self-adaptors and without indicated that there is a dichotomy on

the impression on the agents between users with high social skills and those with low skills. People with

high social skills feel more friendliness toward an agent that exhibits self-adaptors than those with low

social skills. The result suggests the need to tailor non-verbal behaviour of virtual agents according to user’s

social skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

Intelligent virtual agents (IVAs) that interact face-to-

face with humans are beginning to spread to general

users, and IVA research is being actively pursued.

IVAs require both verbal and nonverbal

communication abilities. Among those non-verbal

communications, Ekman classifies gestures into five

categories: emblems, illustrators, affect displays,

adapters, and regulators (Ekman, 1980). Self-

adaptors are non-signalling gestures that are not

intended to convey a particular meaning (Waxer,

1988). They are exhibited as hand movements where

one part of the body is applied to another part of the

body, such as picking one’s nose, scratching one’s

head and face, moistening the lips, or tapping the

foot. Many self-adaptors are considered taboo in

public, and individuals with low emotional stability

perform more self-adaptors, and the number of self-

adaptors increases with psychological discomfort or

anxiety (Ekman, 1972, Waxer, 1988, Argyle, 1988).

According to Caso et al. self-adaptor gestures were

used more often when telling the truth than when

lying (Caso, 2006).

Because of its non-relevance to conversational

content, there has not been much IVA research done

on self-adaptors, compared with nonverbal

communication with high message content, such as

facial expressions and gazes. Among few research

that has dealt with an IVA with self-adaptors, Neff

et al. reported that an agent performing self-adaptors

(repetitive quick motion with a combination of

scratching its face and head, touching its body, and

rubbing its head, etc.), was perceived as having low

emotional stability. Although showing emotional

unstableness might not be appropriate in some social

interactions, their finding suggests the importance of

self-adaptors in conveying a personality of an agent

(Neff, 2011).

However, self-adaptors are not always the sign

of emotional unstableness or stress. Blacking states

self-adaptors also occur in casual conversations,

where conversant are very relaxed (Blacking, 1977).

Chartrand and Bargh

have shown that mimicry of

particular types of self-adaptors (e.g., foot tapping and

face scratching) can cause the mimicked person to

perceive an interaction as more positive, and may lead

to form rapport between the conversants

(Chartrand,

1999).

We focus on these “relaxed” self-adaptors

performed in a casual conversation in this study. If

those relaxed self-adaptors occur with a conversant

that one feels friendliness, one can be induced to feel

friendliness toward a conversant that displays self-

adaptors. We apply this to the case of agent

conversant, and hypothesize that users can be

induced to feel friendliness toward the agent by

115

Koda T. and Higashino H..

Importance of Considering User’s Social Skills in Human-agent Interactions - Is Performing Self-adaptors Appropriate for Virtual Agents?.

DOI: 10.5220/0004751801150122

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2014), pages 115-122

ISBN: 978-989-758-016-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

adding self-adaptors to the body motions of an

agent.

Because self-adaptors have low message content

and are low in relevancy to the contents of

conversations, they are believed to be actions that

are easily ignored during a conversation. Social

skills, on the other hand, are personal characteristics

that make interpersonal relationships smooth. They

are defined as “skills that are instrumental in

conducting smooth personal relationships” (Hayashi,

1982). People with high social skills are believed to

be able to read nonverbal behaviours in

communication with partners and use them

advantageously in communication. Furthermore,

persons with high social skills are believed to have a

tendency to use a great amount of nonverbal

communication behaviours in order to make

communication with conversation partners richer.

We focused on this characteristic of social skills and

considered that it could have the same effect when

applied to non-verbal behaviour of an agent.

Psychologists have found that people prefer

personalities similar to their own (Izard, 1960, Duck,

1973). Reeves and Nass’ research on the social

responses of people to media indicated users showed

a tendency to prefer computers with personalities

similar to theirs (Reeves, 1996). These findings

suggest that users would also prefer agents with

similar personalities. Because of the characteristics

of social skills, we conjectured that people with high

social skills would consider self-adaptor-performing

agents to have personalities similar to theirs. Thus,

in this study, we made the following hypothesis:

“Compared with people with low social skills,

people with high social skills have a greater sense of

friendliness toward an agent that exhibits self-

adaptors.” We conducted an experiment to verify

this hypothesis.

Many research studies have been done on

interactions between agents and users. However,

most of these studies evaluate transient interactions;

there have been few studies evaluating continued

interactions between agents and users. One

representative study is research on relational agents

by Bickmore. They state that building trust is critical

for continued interactions between users and agents

(Bickmore, 2001, Bickmore 2010, Vardoulakis,

2012). In our study, we took the view that

impressions of self-adaptors in informal

communication are formed through multiple

interactions. Thus, we did not evaluate impressions

after one trial, but instead evaluated multiple

interactions between agents and users by conducting

multiple trials and evaluations. We believe the

results of this study can be applied to the

development of agent applications that require long-

term interactions, i.e., counselling agents, by

evaluating the effects of displaying self-adaptors

with IVAs.

2 EXPERIMENTAL

CONVERSATIONAL AGENT

We conducted a pre-experiment in order to examine

when and what kind of self-adaptors occur during a

casual conversation between friends. We invited

four pairs who are friends for more than three years

(they are university students who study together) to

record their conversation. The recordings were more

than 20 minute long but we evaluated the last 10

minutes when the conversation was active and they

were not nervous about being videotaped. Based on

the results of video analysis of the conversations, we

found the following three types of self-adaptors

occurred most frequently in most pairs: “touching

hair,” “touching cheek,” and “touching nose.” Each

stroke occurred once as a slow movement. The

timing was either at the beginning or at the end of an

utterance. The self-adaptors implemented for the

agents in (Neff, 2011) were repetitive quick hand

scratches, rubbing, tapping, etc., as we see when the

human conversant is nervous. We did not find those

nervous repetitive movements during the casual

conversations in the pre-experiment.

The agent character and animation of the three

types of self-adaptors were created using Poser

(http://poser.smithmicro.com/poser.html). Figure 1

shows the agent carrying out the movements of

“touching hair”, “touching nose”, and “touching

cheek”. We found no literature that explicitly

described the form of the movement (e.g., how the

nose has been touched, in which way, by which part

of the hand etc.), we mimicked the form of the

movements of the participants in the pre-experiment.

Besides these self-adaptors, we created animation of

the agent making the gestures of “tilting its head”

and “placing its hand against its chest.” These

gestures were carried out by the agent at appropriate

times in accordance to the content of the

conversation (“head tilting” at the end of a question,

“hand against chest” when addressing the agent

itself) regardless of experimental conditions in order

not to let self-adaptors stand out during a

conversation with the agent.

The agent’s conversation system was developed

in C++ using Microsoft Visual Studio 2008. The

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

116

agent’s voice was synthesized in a woman’s voice

using the Japanese voice synthesis package AITalk

(http://www.ai-j.jp/). The contents of the

conversations were casual (the route to school,

residential area, and favourite food, etc.).

Conversation scenarios, composed of questions from

the agent and response choices, were created

beforehand, and animation of the agent that reflected

the conversational scenario was created. By

connecting animated sequences in accordance of the

content of the user’s responses, the system realized a

pseudo-conversation with the user. The conversation

system had two states. The first state was the agent

speech state, in which an animated sequence of the

agent uttering speech and asking questions to the

user was shown. The other state was the standby for

user selection state, in which the user chose a

response from options displayed on the screen above

the agent. In response to the user’s response input

from a keyboard, animated agent movie that

followed the conversation scenario was played back

in the speech state.

The interaction between the agent and a

participant was restricted as a pseudo conversation.

1) The agent always asks a question to the

participant. 2) Possible answers were displayed on

the screen and the participant selects one answer

from the selection from a keyboard. 3) The agent

makes remarks based on the user’s answer and asks

the next question. The agent performs three self-

adaptors during one interaction in the “with self-

adaptor” condition. The reason we adopted the

pseudo-conversation method was to eliminate the

effect of the accuracy of speech recognition of the

users’ spoken answers, which would otherwise be

used, on the participants’ impression of the agent.

3 EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

The participants in the experiment were 24 Japanese

undergraduate and graduate students (12 male and

12 female), aged 19-24 years. Their social skills

were measured beforehand using KiSS-18 (Kikuchi's

Scale of Social Skills: 18 items) (Kikuchi, 2004).

KiSS-18 is a widely used scale for social skills in

social, clinical, industrial, and educational

psychology as well as nurse-education. Before the

start of the experiment, they were separated into a

high social skills (HSS) group and a low social skills

(LSS) group. Because the average scores on the

social skill scale for Japanese adult males and

females are 61.82 and 60.10, respectively (Kikuchi,

2004), we used these scores as reference and

Figure 1: Agents that exhibit “touching hair” (top),

“touching nose” (middle), and “touching cheek” (bottom)

self-adaptors.

established the HSS group as having a score of 63 or

above (11 participants) and the LSS group as having

a score of 58 or below (13 participants).

The participants in the HSS group and the LSS

group each carried out five rounds of conversation

with either an agent that performed self-adaptors (7

participants in the HSS group and 7 participants in

the LSS group) or an agent that did not perform self-

adaptors (4 participants in the HSS group and 6

participants in the LSS group). Each participant

conducted one conversation with the agent per day,

and the type of agent (with or without self-adaptors)

was kept the same for all trials of the experiment.

The duration of one interaction is about 2 minutes.

The difference between the two types of agents lay

only in whether or not that the agent performed self-

adaptors. The agents’ appearance, voice, timing and

number of gestures (tilting its head and placing its

hand against its chest), and conversation contents

were the same. Also, we prepared five conversation

scenarios so that the contents of conversations would

differ for each experimental trial. The order of the

conversation scenarios for the trials was the same

regardless of the type of agent. For the second trial

and after, expressions such as “I’m glad we can talk

again” were included to express the fact that this was

not the first time the participant was conversing with

the agent. The conditions of the experiment were

ImportanceofConsideringUser'sSocialSkillsinHuman-agentInteractions-IsPerformingSelf-adaptorsAppropriatefor

VirtualAgents?

117

social skills (HSS group, LSS group), type of agent

(with self-adaptors, without self-adaptors), and trial

number (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th).

After each conversation, the participated rated

their impressions on the agent using a semantic

differential method on a scale from 1 to 6. For the

participants’ evaluation of impressions, a total of 23

pairs of adjectives, consisting of the 20 pairs from

the Adjective Check List (ACL) for Interpersonal

Cognition for Japanese (Hayashi, 1982) and three

original pairs (concerning the agent’s “humanness,”

“annoyingness,” and “naturalness”), were used. The

list of adjectives is shown in Table 1 in the result

section. After the end of the 5th trial, a post-

experiment survey was conducted in order to

evaluate the participants’ subjective impression of

overall qualities of the agent, such as the naturalness

of its movements and synthesized voice.

4 RESULTS

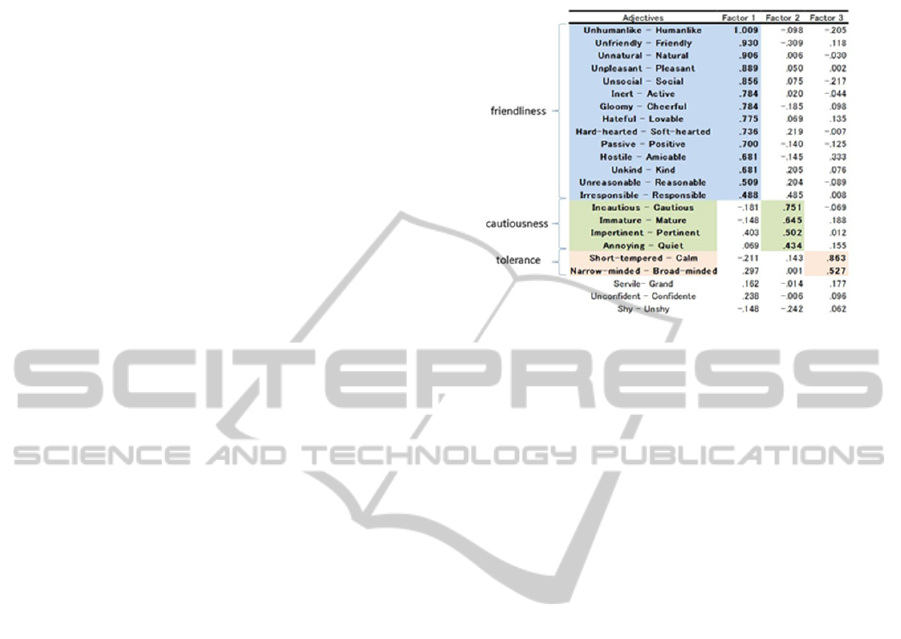

4.1 Analysis of Friendliness Factor

Factor analysis (FA) was conducted on the agent’s

impression ratings obtained from the experiment.

The results of FA using the principal factor method

are shown in Table 1. Three factors were extracted,

and we named them as “friendliness” “cautiousness”

and “tolerance.” We see that when the participants

perceive the agents interpersonally and rate their

impressions, these three factors have a large effect.

The first factor “friendliness” is composed of

adjectives such as humanlike, friendly, natural,

pleasant, and social. The second factor

“cautiousness” is composed of adjectives such as

cautious, mature, pertinent, and quiet. The third

factor “tolerance” is composed of adjectives such as

calm, and broad-minded.

We totalled the measured scores of adjectives

highly correlated to each FA-extracted factor (high

factor loadings), then we used the total score of each

factor for analyses. We ran three-way ANOVA with

factors “social skills” (HSS, LSS), “self-adaptors”

(with, without), and “number of trials” (1st, 5th)

(repeated measures). The dependent variable was the

total score on perceived friendliness of the agent.

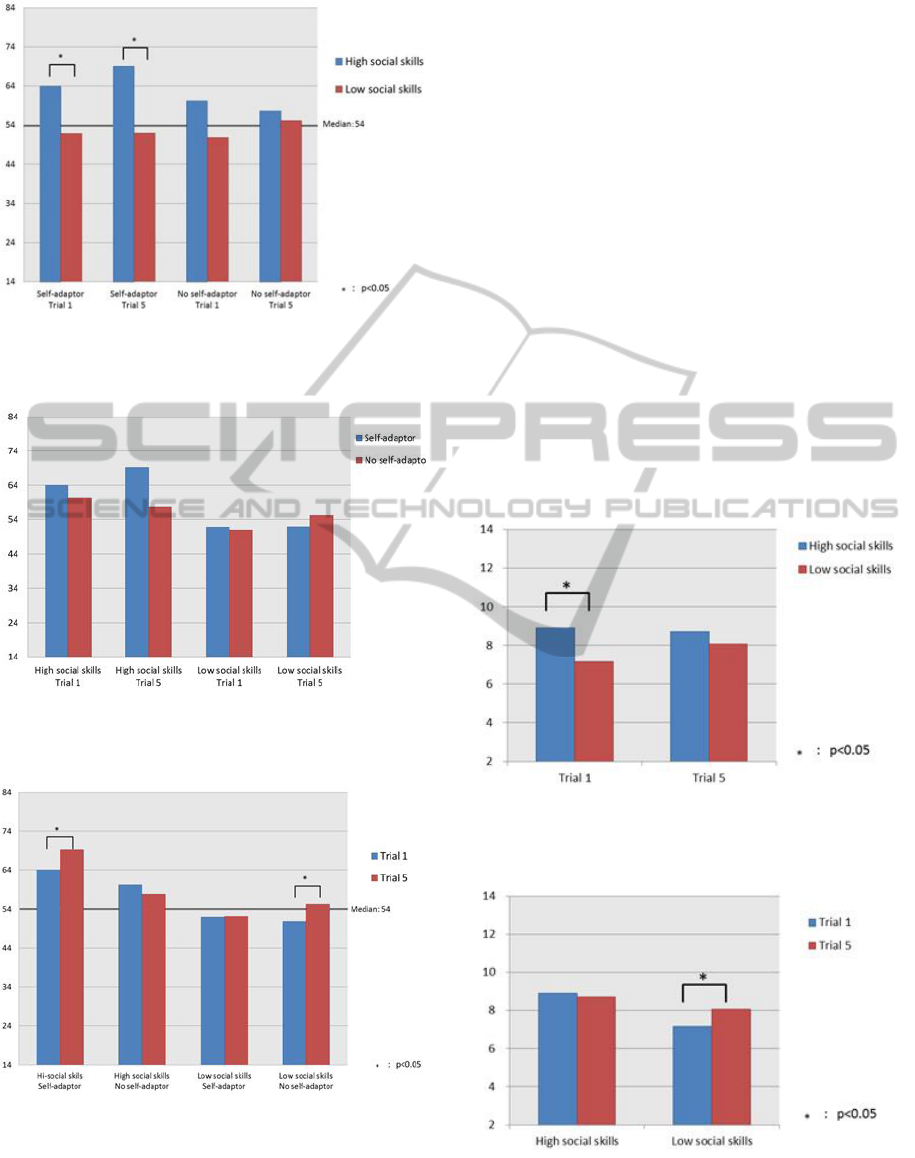

For friendliness, significant second-order

interaction (p<0.01) was seen between the factors

social skills, self-adaptors, and number of trials.

Figure 2 shows the results of multiple comparisons

of friendliness by social skills for treatments of self-

adaptors and number of trials. Significant

Table 1: Results of Factor Analysis (after Promax

rotation).

differences of friendliness ratings (p<0.05) are seen

between the social skills in the condition of “with

self-adaptors in the 1st trial” (HSS group: 64.0 (SE

8.0) > LSS group: 51.9 (SE 11.6)) and of “with self-

adaptors in the 5th trial” (HSS group: 69.1 (SE 6.5)

> LSS group: 52.0 (SE 13.2)). Compared with the

LSS group, the HSS group rated significantly higher

friendliness toward the self-adaptor-performing

agent after both the 1st and the 5th trial.

Next, the results of multiple comparisons of

friendliness by self-adaptors for treatments of the

factors social skills and number of trials are shown

in Figure 3. No significant difference between with

self-adaptor and without could be seen for any of the

treatments of social skills and number of trials.

The results of multiple comparisons of

friendliness by number of trials for treatments of

social skills and self-adaptors are shown in Figure 4.

A significant difference of friendliness ratings

(p<0.05) are seen between the 1st trial and the 5th

trial in the condition of “high social skills and with

self-adaptors” (1st: 64.0 (SE 8.0) < 5th: 69.1 (SE

6.5)), and of “low social skills and without self-

adaptors” (1st: 51.9 (SE 11.6) < 5th: 55.2 (SE 16.3)).

Participants in the HSS group evaluated agents that

performed self-adaptors to be significantly friendlier

after the 5th trail than after the 1st trial. Participants

in the LSS group rated agents that did not perform

self-adaptors to be significantly friendlier after the

5th trial than after the 1st trial.

Three-way ANOVA of social skills, self-

adaptors, and number of trials was con-ducted using

cautiousness’s scale of measurement. None of the

factors showed significance in their main effects and

interactions.

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

118

Figure 2: Results of Multiple Comparisons of Friendliness

Scores by Social Skills for Treatments of self-adaptors and

Number of Trials.

Figure 3: Results of Multiple Comparisons of Friendliness

Scores by Self-adaptors for Treatments of the Factors

Social Skills and Number of Trials.

Figure 4: Results of Multiple Comparisons of Friendliness

Scores by Number of Trials for Treatments of Social

Skills and Self-adaptors.

4.2 Analysis of Tolerance Factor

We ran three-way ANOVA with factors “social

skills” (HSS, LSS), “self-adaptors” (with, without),

and “number of trials” (1st and 5th) (repeated

measures). The dependent variables were

participants’ ratings on perceived tolerance of the

agent. Significant first-order interaction (p<0.05)

was seen between social skills and number of trials.

The results of multiple comparisons of tolerance

scores by social skills for treatments of number of

trials are shown in Figure 5. For the 1st trial, a

significant difference between social skills is seen

(p<0.05; HSS group: 8.9 (SE 1.4) > LSS group: 7.2

(SE 1.9)). In the case of the 1st trial, compared with

the LSS group, the HSS group evaluated the agent to

be significantly more tolerant.

The results of multiple comparison of number of

trials for the treatment of social skills factor are

shown in Figure 6. For participants with low social

skills, significant difference is seen between the

number of trials (p<0.05; 1st trial: 7.2 (SE 1.9) < 5th

trial: 8.1(SE 1.6)). Participants in the LSS group

evaluated the agent to be significantly more tolerant

after the 5th trial than after the 1st trial.

Figure 5: Results of Multiple Comparison of Tolerance

Scores by Social Skills for Treatments of Number of

Trials.

Figure 6: Results of Multiple Comparisons of Tolerance

Scores by Number of Trials for the Treatment of Social

Skills.

ImportanceofConsideringUser'sSocialSkillsinHuman-agentInteractions-IsPerformingSelf-adaptorsAppropriatefor

VirtualAgents?

119

4.3 Analysis of Post-Experiment

Survey

A two-way ANOVA of social skills and self-

adaptors was conducted using the post-experiment

survey’s scores (given on 8-point scale from 1: Low

to 8: High). Significant interaction (p<0.05) between

social skills and self-adaptors is seen for the

question, “Were you bothered by the agent’s

actions?” The results of multiple comparisons of

self-adaptors for each level of the social skills factor

showed a significant difference in self-adaptors

(p<0.05; with self-adaptor: 5.43 > without self-

adaptor: 3.83) for the LSS group. The LSS group felt

significantly more bothered by the agent with self-

adaptors than by the agent without self-adaptors.

Concerning the question, “Was it easy to listen to

the agent’s voice?” social skills’ main effect was

significant (p<0.05). Compared with the LSS group

(4.69), the HSS group evaluated the agents as

significantly easier to listen to (6.18).

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Discussion of Results of Analysis of

Friendliness Factor

From Figure 2, we see that compared with the LSS

group, the HSS group felt a significantly higher

sense of friendliness toward the agent with self-

adaptors, both after the 1st trial and the 5th trial.

From this finding, we can say that regardless of the

number of trials in this experiment, the HSS group

had a significantly higher sense of friendliness

toward the agent that performed self-adaptors than

the LSS group did. Also, because there was not

much difference between the LSS group’s scores for

the condition of self-adaptors and number of trials,

we believe that it was not the case that the LSS

group did not have a sense of friendliness toward the

agent with self-adaptors; rather, the HSS group felt a

stronger sense of friendless toward the agent. This

result supports the hypothesis, “Compared with

people with low social skills, people with high social

skills feel a greater sense of friendliness toward the

agent that exhibits self-adaptors.”

From Figure 3, we see that the results of multiple

comparisons of friendliness scores by self-adaptors

for treatments of the social skills and number of

trials show that there was no significant difference

between “with self-adaptors” and “without self-

adaptors” for any of the treatments of social skills

and number of trials. This result suggests that there

was no significant difference in friendliness due to

only self-adaptors. Although not significant, there

was relatively a large difference in the friendliness

scores between self-adaptor conditions for the HSS

group, but only a small difference was seen for the

LSS group. This finding also suggests that it was not

that the LSS group lacked a sense of friendliness

toward the agent with self-adaptors, but rather, the

HSS group felt a stronger sense of friendliness

toward the agent with self-adaptors.

Figure 4 indicates that the HSS group rated the

agent with self-adaptors as significantly friendlier

after the 5th trial than after the 1st trial. The LSS

group rated the agent without self-adaptors as

significantly friendlier after the 5th trial than after

the 1st trial. From this finding, we can say that when

it comes to continued interactions with an agent, a

sense of friendliness increased for the HSS group as

a result of the agent’s performing self-adaptors. In

contrast, a sense of friendliness increased for the

LSS group as a result of the agent’s without self-

adaptors. This result also supports our hypothesis.

Also, because in continued interactions with the

agent the LSS group experienced an improved sense

of friendliness toward the agent without self-

adaptors, in contrast to the HSS group’s

experiencing an improved sense of friendliness

toward the agent with self-adaptors, we can say that

there is a dichotomy between the evaluation of

friendliness by the HSS group and the LSS group

with regards to the agent performing self-adaptors.

From these results, our hypothesis was supported.

They also suggest the need to develop agents that

meet the level of the users’ social skills when

enabling agents with self-adaptors. Also suggested

by the results is the possibility that a sense of

friendliness toward the agent by users can be

increased in a continual manner by taking into

account the level of the users’ social skills and

whether or not to have the agent perform self-

adaptors during continued interactions.

5.2 Discussion of Results of Analysis of

Tolerance Factor

Figure 5 indicates that compared with the LSS group,

the HSS group rated the agent as significantly more

tolerant after the 1st trial. Figure 6 indicates that the

LSS group rated the agent as significantly more

tolerant after the 5th trial than after the 1st trial.

These results suggest that although the LSS

group did not rate the agent as tolerant compared

with the HSS group, their evaluation of tolerance

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

120

increased during continued interactions with the

agent. On the contrary, the HSS group’s evaluation

of the agent’s tolerance did not increase during

continued interactions. However, the HSS group

rated the agent as more tolerant than the LSS group

did from the first interaction.

5.3 Discussion of Post-Experiment

Survey

Regarding the question, “Did you feel bothered by

the agent’s actions?” the LSS group was

significantly more bothered by the agent with self-

adaptors than the agent without. This result is related

to the LSS group’s low evaluation of the friendliness

of the agent with self-adaptors. Being bothered by

the agent’s actions affected the evaluation of

friendliness negatively. For the LSS group, “being

bothered” was probably considered the same as “not

being able to stand it.” Because no difference in the

bothered-ness was seen between self-adaptor

conditions for the HSS group, this suggests that the

LSS group had an oversensitive response to the

agent’s performance of self-adaptors.

Regarding the question, “Was it easy to listen to

the agent’s voice?” the HSS group rated the agents’

voice as significantly easy to listen to compared with

the LSS group. The agent’s voice was the exactly

the same for the HSS group and LSS group. The

results suggest the possibility that in general, the

HSS group had positive view of the agent, whereas

the LSS group had a negative view of the agent.

5.4 Limitations and Future Work

This research is still at a starting phase, thus has

several limitations. Firstly, we need to conduct more

fine grained study on the self-adaptor in human-

human interactions. For example, we need to

conduct close observations on the form and

movements of self-adaptors with larger samples. In

this research we had only four pairs of conversations.

Secondly, on the implementation of self-adaptors

to the agent, our next work should include both

relaxed and stressful self-adaptors. While we used a

female figure of an agent in this experiment,

implementing a male agent and evaluation by both

genders are also needed.

Thirdly, we cannot exclude the effects of the

conversational content when evaluating perceived

impression on the agent. Although self-adaptors are

indirectly related to what is being said, and we

carefully designed the conversation scenarios so as

not to leave any particular impression on the topic, it

is hard to evaluate self-adaptors completely isolated

from the content of the conversation.

Future work should also consider cultural

differences in expressing and perceiving self-

adaptors, since there are culturally-defined

preferences in bodily expressions (Johnson, 2004,

Rehm, 2007, Rehm, 2008, Aylett, 2009) and in

facial expressions (Koda, 2009, Rehm, 2010), and

allowance level of expressing non-verbal behaviour

are culture-dependant.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest the importance of changing the

level of displaying self-adaptors of IVAs according

to the users’ social skills. The dichotomy between

the use’s social skills suggests that it is possible to

continually improve users’ sense of friendliness

toward IVAs by combining the presence of self-

adaptors with the user’s level of social skills during

continued interactions with agents. We believe that

it is possible to efficiently elicit users’ sense of

agent’s friendliness for both people with high social

skills and with low social skills by finely adjusting

the appropriate timing of the agent’s performances

of self-adaptors and their frequency depending the

user’s level of social skills. Because users with high

social skills frequently make nonverbal movements

such as gestures and nods, and users with low social

skills have a low frequency of these nonverbal

movements, it is possible to use tools such as Kinect

sensors to detect users’ movements and frequency

during conversations and estimate their level of

social skills. If we can develop agents that use the

estimation results to automatically control the

number and frequency of self-adaptors and draw out

a sense of friendliness from users, we can sustain

high-quality agent interactions. The results of this

research could be applied to the development of

IVAs with which users require long-term interaction,

such as counselling agents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by a Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) 23500266) (2011-2013)

from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

ImportanceofConsideringUser'sSocialSkillsinHuman-agentInteractions-IsPerformingSelf-adaptorsAppropriatefor

VirtualAgents?

121

REFERENCES

Argyle, M., 1988. Bodily communication. Taylor &

Francis.

Aylett, R., Vannini, N., Andre, E., Paiva, A., Enz, S., Hall,

L., 2009. But that was in another country: agents and

intercultural empathy. In Proceedings of The 8th

International Conference on Autonomous Agents and

Multiagent Systems-Volume 1. pp. 329-336.

International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and

Multiagent Systems.

Bickmore, T. and Cassell, J., 2001. Relational Agents: A

Model and Implementation of Building User Trust, In

Proc. of CHI 2001, pp. 396-403. ACM Press.

Bickmore, T, Schulman, D, Yin, L., 2010. Maintaining

Engagement in Long-term Interventions with

Relational Agents. In International Journal of Applied

Artificial Intelligence special issue on Intelligent

Virtual Agents 24(6), pp. 648-666.

Blacking,j.,(ed)., 1977. The Anthropology of the Body,

Academic Press.

Caso, L., Maricchiolo, F., Bonaiuto, M., Vrij, A., and

Mann. S. 2006. The Impact of Deception and

Suspicion on Different Hand Movements. Journal of

Nonverbal Behavior, 30(1), pp. 1-19.

Chartrand, T. L., and Bargh, J. A. 1999. The chameleon

effect: The perception–behavior link and social

interaction. Journal of Personality & Social

Psychology, 76, pp. 893–910.

Duck, S.W. 1973. Personality similarity and friendship

choice: Similarity of what, when? Journal of

Personality, 41(4), pp. 543–558.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W.V., 1972. Hand movements. In

Journal of Communication 22, pp. 353-374.

Ekman P., 1980. Three classes of nonverbal behavior. In

Aspects of Nonverbal Communication. Swets and

Zeitlinger.

Hayashi, T., 1982. The Measurement of Individual

Differences in Interpersonal Cognitive Structure. In

Experimental Social Psychology 22, pp. 1-9 (in

Japanese).

Izard, C. 1960. Personality similarity and friendship. The

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 61(1), pp.

47-51.

Johnson, W., Marsella, S., Mote, N., Viljhalmsson, H.,

Narayanan, S., Choi, S., 2004. Tactical language

training system: Supporting the rapid acquisition of

foreign language and cultural skills. In Proc. of

InSTIL/ICALLNLP and Speech Technologies in

Advanced Language Learning Systems.

Kikuchi, A., 2004. Notes on the researches using KiSS-18

Bulletin of the Faculty of Social Welfare. Iwate

prefectural university (in Japanese).

Koda, T., Ishida. T., Rehm, M., and Andre, E., 2009.

Avatar culture: cross-cultural evaluations of avatar

facial expressions. In Journal of AI & Society, Vol.24,

No.3, pp.237-250. Springer London.

Neff, M., Toothman, N., Bowmani, R., Fox Tree, J. E.,

Walker, M., 2011. Don’t Scratch! Self-adaptors

Reflect Emotional Stability. In Vilhjalmsson, H. H. et

al. (Eds.): IVA 2011, LNAI 6895, pp. 398-411.

Springer-Verlag.

Reeves, B. and Nass, C., 1996. Media Equation : How

People Treat Computers, Television and New Media

like Real People and Place. Univ. of Chicago Press

.

Rehm, M., Andre, E., Bee, N., Endrass, B., Wissner, M.,

Nakano, Y., Nishida,T., Huang, H., 2007. The cube-g

approach -coaching culture-specific nonverbal

behavior by virtual agents. In Organizing and learning

through gaming and simulation: proc. of Isaga 2007 p.

313.

Rehm, M., Nakano, Y., Andre, E., Nishida, T., 2008.

Culture-specific first meeting encounters between

virtual agents. In Intelligent virtual agents. pp. 223-

236. Springer-Verlag.

Rehm, M., Nakano, Y., Koda, T., and Winschiers-

Theophilus, H., 2010. Culturally Aware Agent

Communications. In Marielba Zacharias, Jose Valente

de Oliveira (eds): Human-Computer Interaction: The

Agency Perspective. Studies in Computational

Intelligence, Vol. 396, pp. 411-436. Springer.

Vardoulakis, L., Ring, L., Barry, B., Sidner, C., and

Bickmore, T., 2012. Designing Relational Agents as

Long Term Social Companions for Older Adults. In

Proc. of Intelligent Virtual Agents conference.

Springer-Verlag.

Waxer, P., 1988. Nonverbal cues for anxiety: An

examination of emotional leakage. In Journal of

Abnormal Psychology 86(3), pp. 306-314.

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

122