Reflections on the Concept of Interoperability in Information Systems

Delfina Soares and Luis Amaral

ALGORITMI Research Center, University of Minho, Campus de Azurém, Guimarães, Portugal

Keywords: Interoperability, Information Systems, Sociotechnical.

Abstract: Information systems interoperability is one of the main concerns and challenges of information systems

managers and researchers, most of whom perceive and approach it on a pure or predominantly technological

perspective. In this paper, we argue that a sociotechnical perspective of information systems interoperability

should be adopted and we set out seven assertions that, if taken into consideration, may improve the

understanding, management, and study of the information systems interoperability phenomenon.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interoperability became a popular term in recent

years, catching the attention of professionals and

researchers of the most various domains.

Despite of its current huge popularity,

interoperability is not a recent term or concern.

According to the Webster’s Timeline History of

Interoperability, this term has been used for decades

in domains such as the military, transportation,

healthcare, public safety, communications, and

computer science (Parker, 2009). More recently,

interoperability has become a central issue for

professionals and researchers in the Information

Systems (IS) domain.

Information systems interoperability is

considered a mandatory issue for organizations’

success, and even for their survival, in the current

networked and globalized world, since it may

increase organizations’ agility and competitiveness,

allow the provision of different and more integrated

services, reduce operation costs, and improve

organization’s efficiency.

Besides being considered as something

mandatory and beneficial, IS interoperability is also

recognized as a complex, challenging, and difficult

to achieve phenomenon. Indeed, many IS

interoperability initiatives have failed to succeed and

much of the money, effort, and time spent in them

have not produced the expected results.

Many of the failures and problems found may be

due to the inadequate interpretation and too narrow

perspective that many practitioners and academics

have on the IS interoperability concept.

Indeed, after a detailed and thorough literature

review on the IS interoperability subject, as well as

the analysis of multiple successful and unsuccessful

IS interoperability practical cases, it is our

conviction that the IS interoperability concept is

many times mainly, or even exclusively, addressed

and treated on a technical perspective. We argue that

a pure technical perspective of IS interoperability

may undermine and jeopardize the achievement of

truly and adequate levels of interoperability between

IS in organizations. Hence, a wider perspective of IS

interoperability concept is needed, not only to

improve the work of professionals as well as of

researchers and academics in IS interoperability

field. Along this paper we will expose some

thoughts that support this argument.

This paper is organized as follows. After this

introduction, in section two we reflect on the

interoperability concept. By analyzing and

comparing multiple definitions found for the term,

we point out a set of key ideas underlying the

concept of interoperability and highlight the

existence of a certain misconception and misuse of

the terms “interoperability” and “integration”. In

section three remarks are made concerning the

interpretation of the interoperability concept in the

IS domain. Based on the thoughts and remarks set

out in sections 2 and 3, as well as on the experience

and knowledge that we gained by conducting

research studies on IS interoperability in public

administration, we advance in section 4 seven

assertions concerning the IS interoperability

phenomenon. Final conclusions are presented in

section 5.

331

Soares D. and Amaral L..

Reflections on the Concept of Interoperability in Information Systems.

DOI: 10.5220/0004969703310339

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 331-339

ISBN: 978-989-758-027-7

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 THE INTEROPERABILITY

CONCEPT

Despite being a term frequently used in current

written and spoken discourses, the meaning of

interoperability remains somewhat ambiguous and

diffuse (Chen, 2005; CompTIA, 2004; Miller, 2000).

Two main aspects seem to justify the ambiguity

regarding the concept of interoperability: (i) the

existence of numerous and different definitions for

the term, each of which highlighting a particular set

of ideas and different perspectives that can be

associated with it, and (ii) the lack of clarity that

exists between the meaning ascribed to

“interoperability” and to “integration”, which is a

term often used as synonym of interoperability.

These two aspects will be discussed in more detail in

the following subsections.

2.1 Key Ideas Underlying the

Interoperability Concept

To better understand the concept of interoperability

a wide range of definitions for this term was

collected from the literature and analyzed (see

Appendix).

As can be seen from Appendix, some of the

definitions are very generic, defining interoperability

in a very broadly way. This is the case, for example,

of the definition found in Compact Oxford English

Dictionary, where the term interoperable is defined

as “able to operate together”. Although this short

definition exposes indeed the central idea underlying

to the term interoperability (the idea of operating

together), it is too generic. This excessive generality

may easily lead to different understandings,

depending on how the terms “operate” and

“together” are interpreted. For example, if “operate”

is interpreted as “run something” and “together” is

interpreted as “physical proximity”, then it is

possible to say that in a situation where two software

systems are both installed and running in the same

machine there is interoperability between them,

which does not correspond, in fact, to the meaning

of this term.

Definition 8, by the IEEE, which considers

interoperability as “the ability of two or more

systems or components to exchange information and

use the exchanged information”, introduces

additional detail, that helps to prevent erroneous

interpretations such as the one described above. In

fact, the two requirements included in the IEEE

definition (one requirement is the existence of an

exchange and the other requirement is the fact that

who gets what is exchanged uses it to do something)

are aspects highlighted in most of the gathered

definitions, being thus considered as two essential

ideas underlying the interoperability concept.

Definition 29 adds to the ability to exchange and use

data the ability of one entity to use functionality of

the other entities.

According to Chen (2005), a situation of

interoperability is characterized by the idea of

“acting on demand”, i.e., one entity does something

in response to a request received from another entity

(the solicitor entity). Thus, there is only

interoperability between two entities A and B if

entity A is able to send its request to entity B and

entity B is able to receive that request, to understand

it and perform something that actually corresponds

to the action that entity A intended to see executed

by entity B in response to the request made.

Another requirement that seems essential for the

existence of interoperability is related to the need of

existing “understanding” between the entities that

exchange the information. In fact, although two

entities may be able to exchange information, there

will only be effective interoperability between them

if they have a shared understanding of the

exchanged information. If this does not occur,

although they could be able to interact, to exchange

information, and use the exchanged information, the

result of these interactions may not correspond to

what would be expected. The need for the existence

of a shared understanding between interoperating

entities is explicit, for example, in definitions 5, 23,

and 25 of Appendix.

According to definitions 19, 24, and 26, another

prime characteristic of interoperability is the fact

that each of the involved entities should be able to

operate without having to know details about the

internal mode of operation of the other entities and

without having to do a significant effort to change its

internal mode of operation.

Two additional ideas characterizing a scenario of

interoperability are still evidenced by some

definitions. One such idea is exposed in definitions

4, 18, 22, and 28 and refers to the fact that entities

should act in order to achieve a common goal or

objective. As regarded by Chen (2005), we can only

achieve true interoperability if the action of

participating entities contributes to the achievement

of a common goal, which is the ultimate goal

intended for the outlined interoperation procedure.

A final key idea is implicit in definitions 3, 8, 10,

11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, and 28 and

refers to the fact that the involved entities are usually

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

332

heterogeneous entities (they were created or

developed in an isolated and independent way) that

operate autonomously. The preservation of this

autonomy of operation is fundamental and thus the

ability to create interoperability between entities

must be achieved with minimum interference in the

autonomy of each one of them.

The ideas pointed out in previous paragraphs

highlight a set of key aspects underlying the

interoperability concept. Given this set of key ideas

– “two or more entities”, “operating together”,

“shared understanding”, “effortless operation”,

“operation with a common goal”, “autonomy”,

“heterogeneity” – we conceive interoperability as

the ability of two or more heterogeneous and

autonomously operating entities to exchange and

use information or functionality of each other,

correctly, conveniently, and without a significant

effort, in order to contribute to the achievement of a

specific purpose.

According to these ideas, the use of the term

interoperability refers to situations where entities

developed in isolation, operating independently, and

exhibiting disparate characteristics are able to

operate jointly to achieve an overall objective, while

maintaining their autonomy and heterogeneity and

without having to know the specific characteristics

of the other entities with which they interoperate.

2.2 Interoperability versus Integration

As mentioned before, another factor contributing to

the ambiguity surrounding the understanding of the

concept of interoperability refers to the absence of

clarity between the terms interoperability and

integration, which are often used in an

indiscriminate and undifferentiated way.

According to the IEEE dictionary, integration

can be defined as “the process of combining

software components, hardware components or both

in an overall system” or as “the merger or combining

of two or more lower-level elements into a

functioning and unified higher-level element with

the functional and physical interfaces satisfied”

(IEEE, 1997: p. 537). The idea of fusion and

unification set out in these definitions is also evident

in the definition of Merriam-Webster online

dictionary, where “integrate” is defined as “to form,

coordinate, or blend into a functioning or unified

whole”, “to unite with something else” or “to

incorporate into a larger unit” (integrate, 2014).

While in a situation of interoperability

participating entities remain autonomous and

independent, so that any of them can be easily

replaced by another with similar specification

without changing the functionality of the overall

system, in a situation of integration participating

entities are assimilated into a larger whole (Busson

and Keravel, 2005; Chen et al. 2008; Dodd et al.,

2003). This may cause serious difficulties and lead

to a loss of functionality of the overall system if any

entity changes or needs to be replaced (Busson and

Keravel, 2005). Integration is thus considered as

extending beyond interoperability, in that, unlike

interoperability, it involves a degree of functional

dependency between the involved entities (Busson

and Keravel, 2005; Chen et al. 2008; EC, 2008;

Faughn, 2002; Panetto and Molina 2008). In this

sense, it can be said that a family of integrated

entities must be interoperable, but interoperable

entities do not necessarily have to be integrated

(Chen and Doumeingts, 2003; Chen et al. 2008;

Panetto and Molina 2008).

Table 1 highlights three differences usually cited

between interoperability and integration.

Table 1: Characteristics of Interoperability and

Integration.

Interoperability Integration

Coexistence Unification

Autonomy Assimilation

Loosely coupled Tightly coupled

Unlike what happens in full integration, in which

the connections between the entities are rigid and

fixed, in interoperability the connections between

entities are more flexible, being easy to establish and

change (Aubert et al., 2003). For this reason,

interoperability assumes a relevant role in complex

and uncertain environments, where involved actors

and relations are unpredictable and dynamic. Indeed,

it is increasingly difficult to fully anticipate the

number and kind of interconnections in which a

given entity (be it a software component, an

application, an information system, an organization,

or whatever kind of entity) will be involved in the

future (Carney and Oberndorf, 2004).

As curiously noted by Sasovova et al. (2001), the

existence of high levels of integration between the

internal systems of an organization may constrain a

set of high level strategic decisions, such as the

decision to sell or dispose an organizational unit or

to outsource some business activities or services. In

situations like those, if the internal systems of the

organization are tightly integrated, a significant

effort will be needed to disintegrate them. According

to the same authors, disintegration efforts may

constitute an even harder and risky task than the task

ReflectionsontheConceptofInteroperabilityinInformationSystems

333

of integrating them. Thus, contrarily to the most

common thought, the existence of a high level of

integration between systems may not be the most

appropriate solution for any given context (Aubert et

al., 2003; Lee and Myers, 2004; Sasovova et al.,

2001; Pavlou and Singletary, 2002), since it may

significantly compromise the agility, flexibility, and

responsiveness of organizations.

3 INTEROPERABILITY

IN INFORMATION SYSTEMS

In the previous section we presented a set of basic

ideas underlying the concept of interoperability,

independently of the domain in which this term is

used. However, a full and rich meaning of the term

is only achieved when it is analyzed and interpreted

in its context of use. This means that when talking

about interoperability between information systems

it is fundamental to understand the implications that

the IS context can bring to the way interoperability

concept is interpreted and treated.

Different perspectives on information systems

can be found in literature. One of such perspectives

envisages IS as sociotechnical systems, i.e., systems

that encompass elements of social and technological

nature.

The coexistence of these two elements is

reflected in some IS definitions, such as the one

advanced by Visala (1991: 349) where information

system is defined as “a social and technical system

that models and provides information about a

universe of discourse”, or in the definition presented

by Alter (1992: 7) for whom “information system is

a system that consists of people, work practices,

technology, and information, which interact in order

to accomplish organizational goals”. The same

perspective is shared by Amaral (1994) that

considers information system as being an abstraction

that results from observing an organization from an

information perspective, as well as the human,

organizational and technological resources involved

in the information gathering, storing, processing and

delivering.

Three central ideas emerge from the above

definitions, namely that an Information System:

i. is an abstraction of the organization, which

means that it is something inherent and

intrinsic to the organization (i.e., if there exists

an organization, there exists its information

system);

ii. is, in its essence, a system of social and human

activity;

iii. is, in its existence, a technologically supported

system (information technologies are

increasingly supporting the organization

information system).

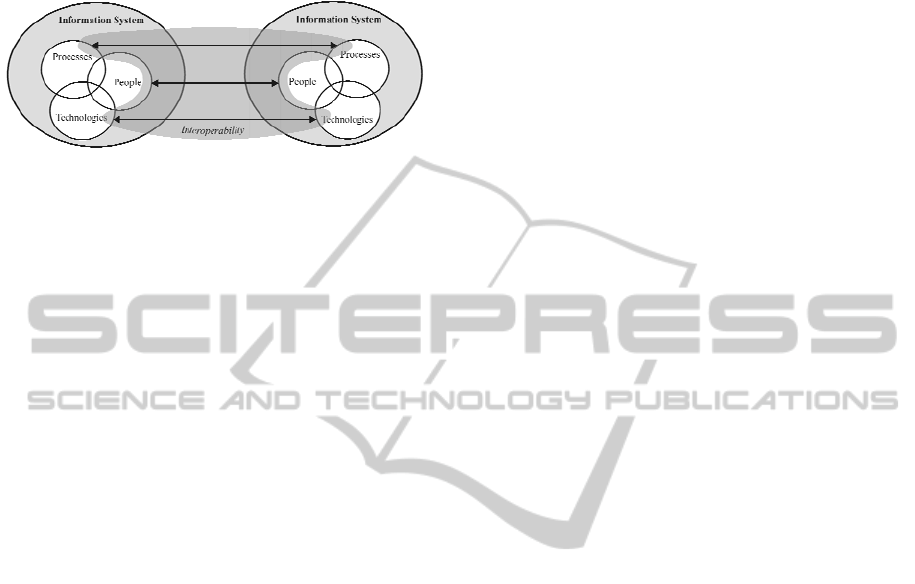

In this sense, as illustrated in Figure 1, people,

processes and technologies are constituting elements

of the information system of an organization:

information in the organization is handled by people

to run a set of organizational processes that

contribute to the achievement of organization’s

objectives and to the fulfillment of organization’s

mission; the execution of the organizational

processes is supported and facilitated by the use of

technologies.

Figure 1: Information System as Sociotechnical System.

The importance that social and organizational

issues assume in the design, development,

management, adoption, and use of information

systems has long been documented in the literature.

According to a survey conducted by Doherty and

King (1998), only 10% of existing faults and failures

in IS development projects were due to

technological issues, with the remaining 90%

attributed to social and organizational issues. These

issues tend to be even more prevalent and

determinant in inter-organizational IS, since the

number and diversity of technologies, organizational

processes, people and interests involved is bigger

(Luna-Reyes et al., 2005).

To considerer information systems as

sociotechnical systems has an immediate

consequence for the discussion set forth in this paper

which is: the phenomenon of “information systems

interoperability” should be perceived, implemented,

managed, and studied in a sociotechnical perspective

(Figure 2). In other words, the process of achieving

true and effective interoperability between

information systems requires more than the mere

connection, understanding and joint operation

capacity of the technological elements of the

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

334

information systems; it requires that this connection,

understanding and joint operation capacity be

extended to the other relevant elements of

information systems: processes and people.

Figure 2: IS Interoperability: A Sociotechnical

Perspective.

Indeed, as stressed in Reach (2004: 6),

“ultimately, interoperability is the result of human to

human agreements; given a human agreement to be

interoperable, technology can help implement that

agreement but no amount of technology can achieve

true interoperability in the absence of human

agreement”. Hence, while the importance of the

technological component is undeniable, human and

social components of this phenomenon should not be

ignored. This view is also shared by Dodd et al. who

consider that interoperability starts first with people.

As the authors recall “sometimes just getting the

right people in the room does wonders for

interoperability, trust and sharing” (Dodd et al.,

2003: 12).

4 ASSERTIONS ABOUT

INFORMATION SYSTEMS

INTEROPERABILITY

The thoughts brought out in previous sections

concerning the concepts of interoperability and of

information systems, and the knowledge that

resulted from previous research studies we

undertook on interoperability in public

administration information systems, led us to

formulate seven assertions about the phenomenon of

IS interoperability, which we believe are relevant

and should frame the way this phenomenon may be

viewed, managed and studied.

A1 - IS Interoperability: A Collective Phenomenon

IS interoperability is a phenomenon that involves at

least two but most of the times many entities. Each

of the involved entities assumes an important role in

it. As so, IS interoperability initiatives and efforts

must be planned, developed, managed and studied as

collective initiatives or efforts. This sets new

challenges to organizations, managers and

researchers and requires from them a new mindset of

cooperative and collaborative work.

A2 - IS Interoperability: Not an Integration

Phenomenon

As argued in section 2.2, although often used

interchangeably, interoperability and integration

terms refer to different phenomena. Due to

unsuccessful past experiences of IS integration,

many of them associated with the implementation of

ERP systems, a misconception of interoperability

and its association with integration initiatives may

generate enormous difficulties and resistances to

accept the IS interoperability phenomenon. For this

reason, it seems fundamental to demystify the

difference between interoperability and integration.

A3 - IS Interoperability: A Federalist Phenomenon

In section 2.1 the preservation of the entities’

autonomy of operation was mentioned as a key idea

underlying the concept of interoperability. This idea

reflects the federalist nature that should characterize

interoperability (Chen, 2005; Daclin, 2005;

Doumeingts and Chen, 2003; Tsagkani, 2005).

Federalism is described by Schwarzenbacher and

Wagner (2005) as the structural and organizational

principle by which separate and autonomous entities

combine efforts to reach a global operation, while

preserving as much as possible, their individuality,

autonomy, and independence.

Indeed, in an interoperability scenario, despite

involved entities should be able to operate together

to promote the image of a whole, their independence

and autonomy should be maintained (Lueders,

2005), thus allowing them to preserve their own

identity and way of working (Daclin, 2005; Lueders,

2005).

This federalist nature represents a valuable

characteristic of interoperability since it can avoid or

mitigate many difficulties and resistances that could

arise if entities would have to change significantly

their way of operating or their information systems.

A4 - IS Interoperability: Not a “Limiter of

Freedom” Phenomenon

Due to the misconception pointed out in assertion

A2, some entities view interoperability as something

that will limit their freedom of choice and action. It

is common to think that “to be able to work and

operate jointly” may imply “to be subject to major

changes and to have to adopt new data formats,

semantics, procedures, and technologies”. This is

not, however, the intent underlying interoperability.

ReflectionsontheConceptofInteroperabilityinInformationSystems

335

As stressed in assertion A3, in an

interoperability scenario each entity should preserve

its autonomy and independence of functioning. In

other words, each entity should be free to organize

its internal data, processes and technologies as it

wants, as soon as it agrees and follows a set of rules

and standards at multiple levels that allows it to

externally connect to, exchange data, and understand

the data exchanged with other entities.

Although some entities may also argue that the

need to adopt and follow a predefined specific set of

standards to be able to interoperate is also something

limiting of their freedom, this seems to us an

excessive argument. Actually, a minimum set of

shared rules and norms between the parts is expected

to exist, otherwise it would be impossible to achieve

any kind of collective action.

Hence, it is fundamental to understand that the

federalist nature of the interoperability phenomenon

reduces to a minimum the lack of freedom of the

entities, since it can increase interoperability

acceptance.

A5 - IS Interoperability: Not an Exclusively

Technological Phenomenon

The existence of interoperability between

information systems requires undoubtedly the ability

of those systems to interoperate at a technological

level. However, as argued, IS are sociotechnical

systems, encompassing other elements besides the

technological ones. Additionally, as pointed in

assertion A1, interoperability is a collective

phenomenon, that may involve multiple entities,

each of them with its organizational, cultural, human

and technological legacy. For this reason, the

challenges around IS interoperability phenomenon

are huge, complex and diverse, tending to be even

more related to organizational, behavioral, and

cultural issues than to technical issues. As such, it

becomes essential to demystify the idea commonly

shared in literature and practice that interoperability

is only, or essentially, a technological challenge.

A6 - IS Interoperability: A Cultural, Social and

Human Phenomenon

Interoperability begins and ends with people.

Ultimately, it is people, with their values, their

perceptions, their beliefs and their experiences that

dictate the success of interoperability between IS: it

is people who think, manage and coordinate the

phenomenon of interoperability; it is people who

define, agree and adopt standards and rules essential

for the achievement of interoperability, and it is

people who fit and align systems and their

interpretative contexts so that the necessary

understanding for the existence of interoperability is

achieved. It is does fundamental to take a broad

perspective, including cultural, social and human

aspects, when studying, implementing, and

managing information systems interoperability.

A7 - IS Interoperability: A Communication,

Negotiation and Diplomacy Phenomenon

Since IS interoperability is a collective phenomenon,

which depends largely on the existence of standards

and agreements between all the involved parts, the

implementation of interoperability between IS

constitutes unavoidably a phenomenon of

communication, negotiation and diplomacy.

Therefore, communication, negotiation and

diplomacy skills are key ingredients in order to

define a consensual set of norms and rules that are

broadly accepted and adopted by the parties.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The assertions set out in last paragraphs derive from

and reflect the widen vision that we have on the

information systems concept information systems

as sociotechnical systems , which consequently led

us to interpret IS interoperability in a sociotechnical

perspective.

This kind of interpretation is not so commonly

found in the literature as we thought. Indeed, most of

the works on IS interoperability treat this

phenomenon in a pure technological perspective.

While calling it IS interoperability, many of the

works end by focusing their attention on IT

interoperability and applications interoperability. In

our opinion, this is not the same thing. The

reflections presented in this paper intend precisely to

call the attention to this fact, and serve as basis for

further discussions on this.

The seven assertions enunciated highlight what

seems to be crucial issues on the phenomenon of IS

interoperability and constitute new insights on how

this phenomenon should be interpreted.

To be aware of these issues seems to be

fundamental for those who are involved in IS

interoperability implementation and management

projects as well as for those that study, research and

try to better understand the phenomenon of

interoperability between information systems. To

have only a partial view of the IS interoperability

phenomenon may threaten the success of many IS

interoperability efforts. Therefore, it is our

conviction that these assertions should reap the

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

336

attention and penetrate the mindset of those involved

in this area and should be taken into account when

implementing and researching in the area of IS

interoperability.

Additional reflections and discussion are needed,

and future work should be done in order to

understand the value of each of those assertions and

their consequences for IS interoperability

practitioners and researches communities.

REFERENCES

Alter, S., 1992. Information Systems: A Management

Perspective, Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Amaral, L., 1994. PRAXIS: Um Referencial para o

Planeamento de Sistemas de Informação. PhD Thesis,

University of Minho, Braga.

Aubert, B., Vandenbosch, B., and Mignerat, M., 2003.

Towards the Measurement of Process Integration.

Available: http://expertise.hec.ca/gresi/wp-content

/uploads/3013/02/cahier0306.pdf (29 Sept 2013).

Busson, A. and Keravel, A., 2005. Interoperable

government providing services: key questions and

solutions analysed through 40 case studies collected in

Europe. In Proceedings of the eGov-Interop'05

Conference, 23-24 February, Geneva, Switzerland.

Carney, D. and Oberndorf, P., 2004. Integration and

Interoperability Models for Systems of Systems.

Available: http://www.sei.cmu.edu/library/assets

/sstcincose.pdf (4 Dec 2013).

Chen, D., 2005. Practices, principles and patterns for

interoperability. Report of INTEROP NoE, FP6 –

Network of Excellence – Deliverable 6.1, May 2005.

Chen, D. and Doumeingts, G., 2003. European initiatives

to develop interoperability of enterprise applications -

basic concepts, framework and roadmap. Annual

Reviews in Control 27(2): 153–162.

Chen, D., Doumeingts, G., and Vernadat, F., 2008.

Architectures for enterprise integration and

interoperability: Past, present and future. Computers in

Industry 59 (7): 647-659.

CompTIA, 2004. European Interoperability Framework -

ICT Industry Recommendations. White Paper.

Daclin, N., 2005. Contribution to a methodology to

develop interoperability of enterprise applications. In

Proceedings of the INTEROP-ESA'05, 23-25

February, Geneva, Switzerland.

Dodd, J., Peat, B., Mayo, D., Christian, E., and Webber,

D., 2003. Interoperability Strategy: Concepts,

Challenges, and Recommendations. Industry Advisory

Council.

Doherty, N. and King, M., 1998. The importance of

Organisational Issues in Systems Development.

Information Technology & People 11(2): 104–123.

EC, 2008. Draft document as basis for EIF 2.0. Draft for

public comments. European Commission.

Faughn, A., 2002. Interoperability: Is it Achievable?

Program on Information Resources Policy. Available:

http://pirp.harvard.edu/pubs_pdf/faughn/faughn-p02-

6.pdf (2 Dec 2013).

IEEE, 1997. The IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical

and Electronics Terms. 6th Edition. New York:

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

integrate, 2014. In Merriam-Webster.com. Available:

http://www.merriam-webster.com/diction ary/integrate

(14 Jan 2014).

Lee, J. and Myers, M., 2004. The Challenges of Enterprise

Integration: Cycles of Integration and Desintegration

Over Time. In Proceedings of the 25th International

Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2004),

December 2004, Washington DC, USA.

Lueders, H., 2005. Interoperability and Open Standards

for eGovernment Services. In Proceedings of the

eGov-Interop'05 Conference, 23-24 February, Geneva,

Switzerland..

Luna-Reyes, L., Zhang, J., Gil-Garcia, R., Cresswell, A.,

2005. Information systems development as emergent

socio-technical change: a practice approach. European

Journal of Information Systems 14(2): 93-105.

Miller, P., 2000. Interoperability: What is it and Why

should I want it?. Available: http://www.ariadne.ac.uk

/issue24/interoperability (29 Sep 2013).

Panetto, H. and Molina A., 2008. Enterprise integration

and interoperability in manufacturing systems: Trends

and issues. Computers in Industry 59 (7): 641-646.

Parker, P., 2009. Interoperability: Webster’s Timeline

History, 1983-2007. California: ICON Group Int.

Pavlou, P. and Singletary, L., 2002. Empirical Study of

Stakeholders' Perceived Benefits of Integration

Attributes for Enterprise IT Applications. In

Proceedings of the 8th Americas Conference on

Information Systems (AMCIS 2002).

Reach, 2004. Reach Interoperability Guidelines:

Interoperability Theory and Practice. Available:

http://sdec.reach.ie/rigs/rig0012/pdf/rig0012_v0_41.pd

f (9 May 2005).

Sasovova, Z., Heng, M. and Newman, M., 2001. Limits to

Using ERP Systems. In Proceedings of the 7th

Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS

2001), Paper 221: 1142-1146.

Schwarzenbacher, K. and Wagner, J., 2005. The

Federative Principle in Business Architecture. In

Proceedings of the INTEROP-ESA'05, 23–25

February, Geneva, Switzerland.

Tsagkani, C., 2005. Inter-Organisational Collaboration on

the Process Layer. In Proceedings of the INTEROP-

ESA'05, 23–25 February, Geneva, Switzerland.

Visala, S., 1991. Broadening the Empirical Framework of

Information Systems Research. In Nissen, H., Klein,

H. and Hirschheim, R. (Eds.), Information Systems

Research: Contemporary Approaches & Emergent

Traditions: 347–364. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

ReflectionsontheConceptofInteroperabilityinInformationSystems

337

APPENDIX

LIST OF DEFINITIONS OF INTEROPERABILITY

1. Interoperable – adjective (of computer systems or software) able to operate in conjunction.

Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English, Third Edition, Oxford University Press, 2005.

2. Interoperability – characteristic that allows the connection and jointly of multiple computers.

Grande Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa,Porto Editora, 2004.

3. Interoperability is the ability to use resources from diverse origins as if they had been designed as parts of a single

system.

Bollinger, T., 2000. A Guide to Understanding Emerging Interoperability Technologies. MITRE

(http://www.mitre.org/work/tech_papers/tech_papers_00/bollinger_interoperability/bollinger_interop.pdf).

4. (A) Interoperability is the ability of systems, units, or forces to provide services to and accept services from other

systems, units, or forces and to use the services so exchanged to enable them to operate effectively together.

(B) The condition achieved among communications-electronics systems or items of communications-electronics

equipment when information or services can be exchanged directly and satisfactorily between them and/or their users.

DOD-NATO JP 1-02 (http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp1_02.pdf).

5. The ability of one system to receive and process intelligible information of mutual interest transmitted by another

system.

[JINTACCS 74] cited in Kasunic, M. and Anderson, W., 2004. Measuring Systems Interoperability: Challenges and Opportunities,

Carnegie Mellon University.

6. Interoperability is the ability of information systems to operate in conjunction with each other encompassing

communication protocols, hardware, software, application, and data compatibility layers.

ICH Glossary of Terms (http://www.ichnet.org/glossary.htm).

Poler, R., Tomás, J. and Velardi, P., 2005. Interoperability Glossary, INTEROP NoE, Deliverable 10.1, Version 1B.

7. Enabling different systems to work together and exchange data.

CETIS Acronyms and Glossary (http://www.cetis.ac.uk/members/enterprise/glossary)

8. (A) Interoperability is the ability of two or more systems or components to exchange information and to use the

information that has been exchanged.

(B) The capability for units of equipment to work together to do useful functions.

(C) The capability, promoted but not guaranteed by joint conformance with a given set of standards, that enables

heterogeneous equipment, generally built by various vendors, to work together in a network environment.

(D) The ability of two or more systems or components to exchange information in a heterogeneous network and use

that information.

IEEE, 1997. The IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics Terms. 6th Edition. New York: Institute of Electrical and

Electronics Engineers.

9. Interoperability is the ability to exchange information and mutually to use the information which has been exchanged.

Council Directive of 14 May 199 on the legal protection of computer programmes (91/250/EEC).

10. Interoperability is the ability of independent, distributed software components to operate together as part of a larger

system.

http://www.canri.nsw.gov.au/glossary.html

11. Interoperability is the ability of computer systems made by different manufacturers to operate with one another.

http://www.iomega.com/europe/support/english/documents/11240e.html

12. Interoperability is the ability to operate and exchange information in a multivendor/multiproduct network.

http://www.networkcables.com/i.htm

13. Interoperability is the ability of software and hardware to communicate and function across multiple machines, under

multiple vendor formats.

http://dli.grainger.uiuc.edu/glossary.htm

http://www.aot.state.vt.us/CaddHelp/cadd/glossary/gloss_i.htm

14. Interoperability is the ability of a network to operate with other networks, such as two systems based on different

protocols or technologies.

http://www.roadtripamerica.com/dashboarding/glossary.htm

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

338

15. Interoperability is the ability of different types of databases, applications, operating systems, and platforms to function

in an integrated manner.

http://www.dddmag.com/scripts/glossary.asp

16. Interoperability is the ability of one manufacturer's computer equipment to operate alongside, communicate with, and

exchange information with another vendor's dissimilar computer equipment.

http://www.networkbuyersguide.com/search/105487.htm

17. Interoperability is the ability to exchange and use information (usually in a large heterogeneous network made up of

several local area networks).

http://www.hyperdictionary.com/dictionary/interoperability

http://www.cogsci.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/webwn

18. Interoperability is the ability of different types of computers, networks, operating systems, and applications to work

together effectively, without prior communication, in order to exchange information in a useful and meaningful

manner.

Dublin Core Metadata Glossary (http://library.csun.edu/mwoodley/dublincoreglossary.html).

19. Interoperability is the ability of content, a subsystem or system to seamlessly work with other systems, subsystems or

content via the use of agreed specifications/standards.

http://www.tasi.ac.uk/glossary/glossary_technical.html

20. Interoperability is the ability of heterogeneous systems and networks to communicate and cooperate through specified

standards.

http://info.louisiana.edu/dept/glosi.html

21. Interoperability is the ability of equipment from multiple vendors to communicate using standardized protocols.

http://www.nationaldatamux.com/G50001.htm

22. Interoperability may be defined as a process that effectively links two or more systems (marketplaces or other service

providers) or organizations in a partial or fully transparent manner (for users).

Scriven, G., "Interoperability in Australian Government E-Procurement - Strategy versus Reality", 7th Pacific Asia Conference on

Information Systems, Adelaide, South Africa, 2003.

23. Interoperability is achieved only if the interaction between two systems can, at least, take place at the three levels: data,

resource and business process with the semantics defined in a business context.

Chen, D. and G. Doumeingts (2003). "European initiatives to develop interoperability of enterprise applications:- basic concepts,

framework and roadmap." Annual Reviews in Control, 27(2): 153-162.

24. Interoperability is the capability to communicate, execute programs, or transfer data among various functional units in a

manner that requires the user to have little or no knowledge of the unique characteristics of those units.

ISO 19119 Services.

25. Interoperability is the ability to share and exchange information using common syntax and semantics to meet an

application-specific functional relationship through the use of a common interface.

ISO16100.

26. In a purely technological perspective, interoperability concerns the ability of two or more ICT assets (hardware devices,

communications devices or software components) to easily or automatically work together. In a business perspective,

the previous definition expands to include the ability of two or more business processes, or services, to easily or

automatically work together.

CompTIA, European Interoperability Framework — ICT Industry Recommendations (White Paper), 2004.

27. Interoperability is the ability of ICT systems and of the business processes they support to exchange data and to enable

sharing of information and knowledge.

IDABC, European Interoperability Framework for pan-European eGovernment Services, 2004.

28. Interoperability is the ability of disparate and diverse organizations to interact towards mutually beneficial and agreed

common goals, involving the sharing of information and knowledge between the organizations via the business

processes they support, by means of the exchange of data between their respective information and communication

technology (ICT) systems.

IDABC, European Interoperability Framework for pan-European eGovernment Services, 2008.

29. Interoperability is defined as the ability to communicate, execute programs, or transfer data among various functional

units due to the use of common languages and protocols, requiring little or no knowledge of the user about the specific

features of these units.

APDSI, 2011, Glossário da Sociedade da Informação (http://www.apdsi.pt/uploads/news/id432/gloss%C3%

Alrio%da%20si%20-%20vers%C3%A3o%202011.pdf)

ReflectionsontheConceptofInteroperabilityinInformationSystems

339