The Adoption and Use of Human Resource Information System

(HRIS) in Ghana

Peter K. Osei Nyame

1

and Richard Boateng

2

1

Methodist University College Ghana, Dansoman, Accra, Ghana

2

University of Ghana Business School, Accra, Ghana

Keywords: HRIS Adoption, e-HRM, Virtual HR, Information Technology, Information System.

Abstract: The study looked at the adoption of Human Resource Information System (HRIS) among Ghanaian firms. A

survey was conducted on 129 firms out of the 150 samples randomly selected from both the public and the

private sectors in the country with a response rate of 86%. The findings first revealed that the adoption rate

of HRIS in enterprises is not a common practice in Ghana since two-thirds of the organizations have never

adopted HRIS use. Major general denominators for adoption and use of HRIS include firm size,

organization type (i.e. profit making limited liability companies and profit making government

organization) and age as well as the industry to which firms belong. Firms attributed the slow rate of

adoption to reasons including the low numbers of employees, high cost of system installation, unawareness

and low priority for such a system. Again, it was realized that the companies’ readiness to adopt such a

system was not encouraging. There were some technical, organizational and environmental factors that

affect HRIS adoption which were unearthed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business effectiveness and organizational efficiency,

performance and profitability have increasingly been

dependent on Information Technology (Ball, 2001;

Lippert and Swiercz, 2005; Troshani et al., 2010;

Yusoff et al., 2010). Information Technology (IT)

has provided the enabling innovative environment

which has assisted HR professionals to provide

efficient and effective service (Hendrickson, 2003).

The shift is partially attributed to emergent

technologies such as Human Resource Information

System (HRIS) also known as Electronic Human

Resource Management (e-HRM) which consists of

systematic procedures and functions for acquiring,

storing, manipulating, retrieving, analyzing and

disseminating pertinent information concerning

organization’s HR (Lippert and Swiercz, 2005). An

HRIS is a set of interrelated components working

together to collect, process, store and disseminate

information (Dessler, 2011), to support decision

making, coordination, control, analysis and

utilization of an organization‘s Human Resource

Management (HRM) activities.

Gueutal and Stone (2005) acknowledged the use

of technologies for HRM practices and policies as

maturing within organizational life. However,

academic involvement in HRIS started relatively late

and is still trying to catch up with practice (Stanton

and Coovert, 2004; Townsend and Bennett, 2003;

Viswesvaran, 2003). Again, HRM (Absar and

Mahmodd, 2011) and IT have drawn the attention of

researchers (Saleem et al., 2011), industry and

academia, nevertheless linkage between the two

disciplines is still at cutting edge and need more

exploration (Mishra and Akman, 2010) especially in

developing economies. Despite these signs of a

growing academic interest (Gueutal and Stone,

2005) with correspondent growth in literature, there

is a broad agreement that research in the area of

HRIS adoption is inadequate (Henriksen and

Mahnke, 2005; Blount and Castleman, 2009;

Troshani et al., 2010), especially the discriminating

factors determining HRIS adoption in developing

countries (Strohmeier and Kabst, 2009; Sateem,

2012; Chen, 2014).

Surveys of HR consultants posit that the number

of organizations adopting HRIS within organizations

elsewhere in Europe and other advanced economies

were continually increasing (CedarCrestone, 2005;

Strohmeier and Kabst, 2009). It is estimated that

about two-thirds of all organizations of developed

130

Osei Nyame P. and Boateng R..

The Adoption and Use of Human Resource Information System (HRIS) in Ghana.

DOI: 10.5220/0005458101300138

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 130-138

ISBN: 978-989-758-098-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

nations such as the United States are far ahead in the

adoption of HRIS (Palvia et al., 2002; Strohmeier

and Kabst, 2009), but the situation is different with

newly industrializing and developing nations

(Thong, 1999). Research on adoption of HRIS is still

in its “youthful phase” especially in Africa.

Developing economies like Ghana are slowly

adopting technological innovation including HRIS.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the

adoption of HRIS in a developing country like

Ghana leveraging technological, organizational and

environmental factors as a crucial endeavour for

adoption success. Specifically, this paper looked at

the adoption of HRIS among Ghanaian firms to gain

better understanding of the contextual factors that

influence HRIS adoption. The research questions to

be addressed are (1) Have Ghanaian firms adopted

the use of HRIS? (2) If they have not, how prepared

are the firms in the adoption of HRIS? (3) What

TOE factors affect the adoption of HRIS?

2 ADOPTION OF HRIS

Indisputably, the role of Information Technology or

Information Systems (IT/IS) in industry and

commerce cannot be over-emphasized (Wilson-

Evered and Härtel, 2009). The literature delineates

HRIS as the application of IT/IS in performing HR

tasks (Strohmeier, 2007). HRIS has essentially

helped many organizations with the effective

management of its human assets (Troshani et al.,

2011). Like all information systems, the use of HRIS

is crucial for the success and profitability of any

organization. Profitability can significantly be

improved by reducing extant monitoring and

controlling the cost of HRM processes (Sateem,

2012). This is evident from the fact that, firms that

use HRIS have enough time to plan, gain sustainable

competitive advantage by applying the system to

influence strategic decision making (Thong, 1999),

organization’s value creation (Shani and Tesone,

2010; Rangriz et al., 2011) and inform or address

many of the key policy and management questions

(Kumar et al., 2013).

There is a gap between HRIS in a technical sense

and its adoption and use by employees and line

managers (Ruël et al., 2007). Adopting HRIS can be

challenging and costly. Again, it can take long

periods of time before pre-adoption benefits become

reality after HRIS is fully assimilated (Ashbaugh

and Miranda, 2002). Actual usage or adoption can

lag by up to about three years what is available.

Firms that undertake technology initiatives with a

view to enable the HR function to focus more on

value-added activities are the ones most likely to

realize its full potential (Shrivastava and Shaw,

2004).

HRIS adoption refers to the adoption of IT/IS in

HRM (Jeyaraj et al., 2006; Strohmeier and Kabst,

2009). Adoption is distinguished into individual

level (technology adoption by individual persons)

and organizational level (technology adoption by

organizations or organizational units) (Jeyaraj et al.,

2006). Adoption also constitutes a process that

comprises of several phases including initiating and

implementing (Jeyaraj et al., 2006; Rogers, 2003).

Other researchers depict the adoption of

technological innovations in three-stage sequence of

initiation, adoption, and implementation (Thompson,

1969; Pierce and Delbecq, 1977) with adoption as

the stage where a decision is made about adopting

the technological innovation.

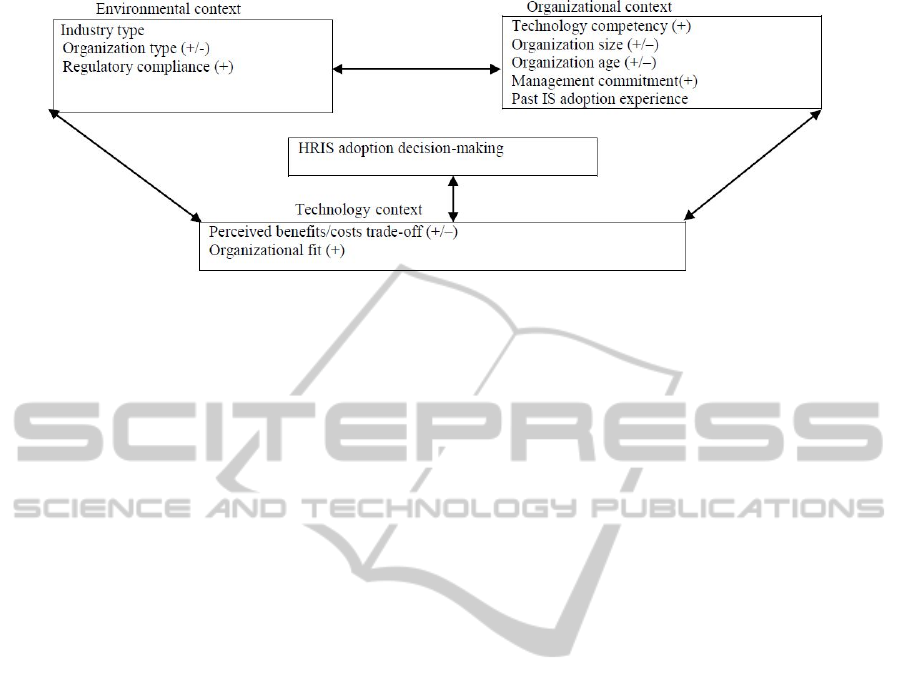

2.1 Theoretical Framework

One of the most established approaches in studying

innovation adoption entails identifying contingency

factors that can affect adoption decisions in

organizations (Fichman, 2004). A useful model that

can be used for the structured analysis of innovation

adoption in organizations have been proposed

(DePietro et al., 1990). Specifically, this model

suggests that decisions to adopt innovations are

shaped by the influence and interaction of generic

factors. Also known as “innovation configuration”

(Fichman, 2004), these factors can jointly explain

adoption outcomes in organizations, and are

commonly classified into three broad categories,

namely, Technology, Organization; and

Environment (TOE) (Tornatzky and Klein, 1982;

DePietro et al., 1990).

Though, the search for relevant and adequate

theory to fully grasp the concept of HRIS and

present fragmented empirical evidence is still

apparent, there are continual demands in the

literature to extend TOE approaches to unexplored

domains including HR/HRIS (Teo, 2007; Dedrick

and West, 2004; Lippert and Swiercz, 2005).

Contrary to general factors, previous research in

HRIS adoption does not refer to contextual factors

alone (Strohmeier and Kabst, 2009). Some

researchers declared that there were abundant fund

of factors offered by previous research which makes

it difficult to select meaningful factors accurately for

HRIS adoption (Jeyaraj et al., 2006). As technology

adoption is complex and context sensitive, specific

factors of each category can vary across different

TheAdoptionandUseofHumanResourceInformationSystem(HRIS)inGhana

131

Figure 1: Innovation Adoption (TOE) Framework.

domains (Kuan and Chau, 2001). This can help to

distinguish between intrinsic innovation

characteristics, organizational capabilities and

motivations, and broader environmental dimensions

that impact on adopters (Dedrick and West, 2004).

For example, contextual variables such as

organizational characteristics, IS characteristics,

environmental characteristics and decision-maker

characteristics as primary determinants of IS

adoption

has been proposed (Thong, 1999). This

study, therefore, adopted the TOE framework

developed by Tornatzky and Fleischer (1990) using

HRIS adoption as a dependent variable with

identifiable set of factors that influence adoption to

include in the model as independent variables: firm

size, industry type, type and age of organizations.

Others were regulatory compliance, technology

competence, management commitment, past IS

adoption, perceived benefit/cost trade off and

organizational fit as shown in figure 1 below.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study was designed to collect data from both

primary and secondary sources. The population for

the study was firms in both the public and private

sector in Ghana. Out of 150 companies randomly

selected, 129 responded and formed part of the

sample size. Though these companies were scattered

across the country, the study was based on

convenience or accessibility sampling since all the

respondents forming majority of the sample were

conveniently accessed in Accra. Organizations were

selected randomly from the Accra Metropolitan

Area from the following broad categories:

Technology/Telecommunication, Services, Manu-

facturing/Production, Mining/Extracting and Trade/

Commerce organizations.

The survey method was used for the research. A

key strength of the survey method involves using

questionnaires, a technique in the data gathering

process which validity could be proven. Whiles the

main research instrument for the primary data

collection was questionnaires, the secondary source

techniques focused on review of textbooks and some

periodicals like journals, reports and magazines as

well as useful reference materials including

electronic databases from the Internet.

150 questionnaires were distributed to firms in

the country. The questionnaires consisted of both

open-ended and closed-ended questions. These

questionnaires were self-administered to the

respondents who completed the questionnaires

without assistance from the researcher after they had

been pilot-tested on five (5) colleagues. Respondents

wereHR or IT managers or their representatives and

had knowledgeable expertise in their fields. They

were encouraged to complete and hand over the

questionnaires in some few minutes to the

researcher. However, respondents who could not

instantly complete the questionnaires were allowed

to keep them and complete at their convenience. The

researcher, therefore, allowed some three days for

this purpose. This made it easy and faster to

distribute the questionnaire widely among

respondents. Follow-ups through personal contact,

phone calls and email notices were cautiously

planned to retrieve the remaining questionnaires.

This made it possible for the researcher to retrieve

greater proportion (86%) of the questionnaires from

the respondents.

The data was cleaned and coded using Statistical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16

programme. Both quantitative and qualitative

techniques were used to create the appropriate

frequency tables and charts like the bar graph to give

a visual or pictorial representation of facts and to

examine the relationships among variables. This also

allowed simple inferences to be made to describe

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

132

variables, summarize and display the data collected

for analyses. Again, descriptive statistical methods

were employed to analyze the data. This made the

presentation vivid for easy conclusions to be drawn.

4 RESULTS

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they

have adopted a system or software to manage their

HR, 51 of them representing 39.5% affirmed the

situation while 78 representing 60.5% stated

otherwise. Generally, it could be seen that the ratio

of companies which have not adopted any system to

manage their HR as against those who have is 3:2 as

shown in the Figure 2 below. This means there were

lots of companies in Ghana which have no system in

place to manage their HR.

Figure 2: Adoption of HRIS.

As a confirmation of the above results,

respondents were asked to state any alternative

method of managing their HR apart from the use of

HRIS, a whopping proportion of almost 95%

indicated that they use the manual system. The low

number of respondents who chose outsourcing

(about 1%) shows that the practice is not common

with Ghanaians as seen from Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Alternative method of managing HR.

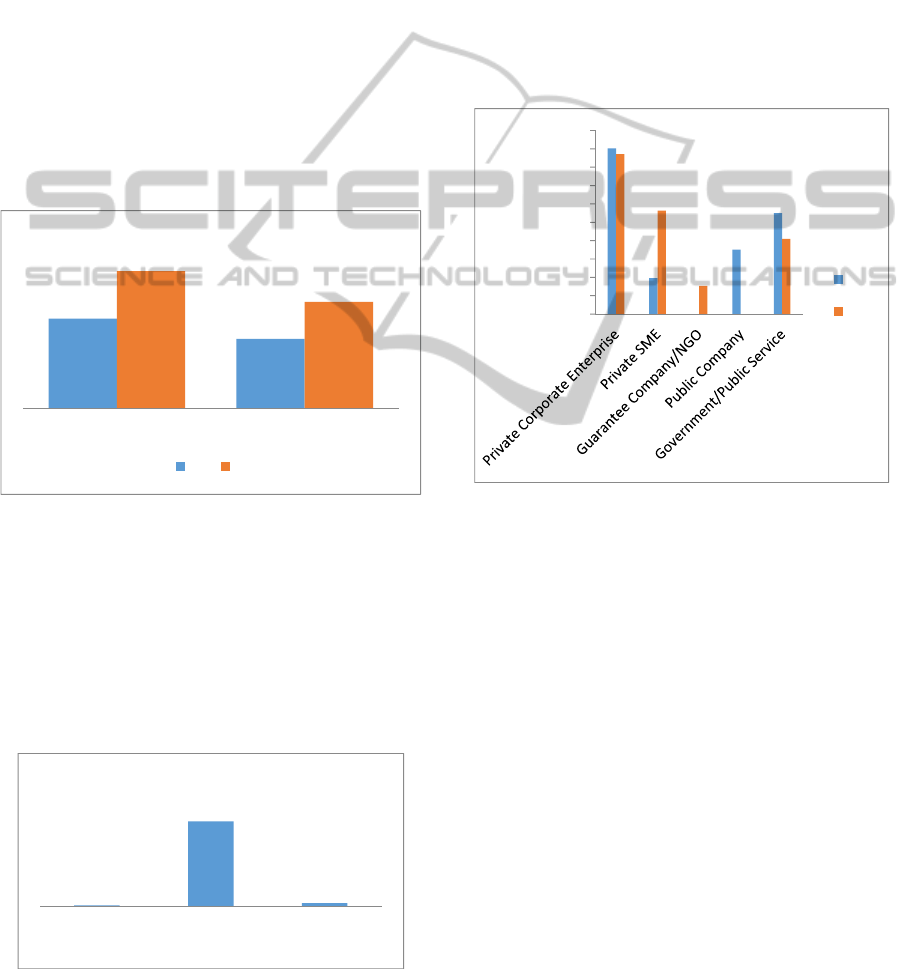

The details from the different organizations were

depicted in the Figure 4 below. 45.1% of the private

corporate companies have adopted HRIS while

43.6% of them did not have. With private SMEs,

9.8% indicated they have a system as against 28.2%

which has no HRIS. For the companies limited by

guarantee, all the 7.7% which formed part of the

sample did not have any system they use to manage

their HR. Again, all the 17.6% of the public

companies forming the sample indicated they have.

With the government and para-governmental

organizations otherwise known as the public sector,

27.5% indicated they have while 20.5% indicated

they did not have.

Figure 4: Distribution of Companies by Organizations.

Like most developing economy, the figure 5

below depict that the Ghanaian industry is

dominated by the service sector with an average of

65%. It is, however, uncommon to find trade and

commerce sector which has an average 15.5%

following the service sector. This is because, as a

developing country, petty trading and commerce is

the livelihood of many of the citizens of the nation.

The low proportion of technology,

telecommunication and manufacturing sectors with

an average of 7.8% apiece tend to reveal the low

level of industrialization that characterizes

developing countries like Ghana. An average of

3.9% goes for the extracting and processing

industry.

51

39,5

78

60,5

Frequency Percentages

Yes No

1,3

94,9

3,8

Outsourcing UseofManual

System

Noresponse

Percent

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Yes

No

TheAdoptionandUseofHumanResourceInformationSystem(HRIS)inGhana

133

Figure 5: Distribution of Companies by Industry.

From the Figure 6 below, it could be seen that

companies which employed less than 50 employees

have as many as about 56% who have not yet

adopted HRIS with only about 10% adopting it. On

the contrary, adoption rate tended to be high with

over 80% adoption rate for companies that

employed over 100 staff. The higher the

employment level, the bigger the size of the

company and the better the adoption rate.

Figure 6: Size of the organization.

Figure 7: Age of organizations.

When the respondents were asked to provide the

age of their firms, it was shown that the older the

firm, the higher the adoption rate. The companies

who were above 11 years tended to have a high rate

of adoption as compared to those with few years of

operation. Out of the 51% which were more than 21

years old, 62.7% have adopted HRIS in their

organizations.

Figure 8 below shows the various reasons given

by respondents for not adopting HRIS in their

workplace. Among the reasons, a whopping number

of about 36% indicated they were not ready to adopt

such a system. About 32% thought they have low

number of staff and therefore it is neither

appropriate nor profitable to adopt such a system.

14% of the respondents were not aware of such a

system while 7.7% apiece of the respondents

attributed their non adoption of HRIS to either the

exorbitant cost of acquisition and installation or as it

was, were indifferent and as such did not answer this

question.

Figure 8: Reason for non-adoption of HRIS.

In response to the issue of whether respondents

were ready to adopt the use of HRIS in their

organizations, about 53% indicated they were ready

while about 39% were not. About 9% did not

respond to the question as shown from the Figure 9

below.

Figure 9: Readiness to adopt the use of HRIS.

From the Table 1 below, respondents were

requested to indicate their extent of readiness and

the period within which they were expected to

implement HRIS. A cursory glance at the figure

depicts that, out of the 53% of the respondents who

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Yes

No

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Yes

No

62,7

Less

than5

years

6‐10

years

11‐15

years

16‐20

years

More

than21

years

Yes

No

0

20

40

52,6

38,5

9

Yes No Noresponse

Percentage

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

134

Table 1: Expected period of organization's readiness to adopt HRIS.

Expected period to start implementing HRIS

Total

Organizational readiness Less than 12 months More than 12 months Not sure/aware Other

Not planned 0 0 7 5 12

Currently exploring 5 6 3 0 14

Currently planning 4 1 2 2 9

Implementation stage 1 0 0 0 1

Other (Please specify) 0 0 0 1 1

Total 10 7 12 8 37

affirmed their readiness to adopt an HRIS, only one

firm hope to implement HRIS within 12 months. 14

of them were currently exploring while 9 were

currently planning. Out of the numbers above, only

10 firms were ready to implement HRIS within the

next 12 months. 7 were ready to implement it after

12 months but within 24 months. 12 have not

planned at all for the implementation of HRIS in

their organization. The 12 who have no plans were

also not aware or sure of when they would ever

implement HRIS.

Finally, respondents were asked to state the

factors that either facilitate or hinder the adoption of

HRIS in their organizations and the following results

were obtained:

• Staff resistance/reluctance to the use of the

systems as a result of lack of understanding of

the application

• Improper coordination and duplication of data

problems

• Customization and adoptability problems

including interfaced with other systems

• Lack of technical expertise to regularly support

the system

• Managers are not ready to support an installation

of a system.

• Wrong data input problems like inconsistency,

inaccuracy, data confusion, loss of data,

mismanagement of data, etc.

• Foreign nature of software makes it difficult to

be used locally

• Inadequate support services for the systems from

the vendors

• Access denial due to infrastructural

unavailability like hardware, software, LAN,

WAN and server breakdown

• Configuration of the system to conform to

company’s policies and procedures

• Systems failure and delay due to internet failure,

power supply failure, etc.

• Migration of data from the old system to the

new.

• The employees are comfortable with the manual

system.

5 DISCUSSION

Undoubtedly, the study first established that about

40% of the firms in Ghanaian business environment

have adopted HRIS though, this was not enough. In

other words, a seeming number of about 60% of the

firms have not adopted HRIS. This means that there

was more room for improvement in the adoption of

HRIS in Ghana. It was therefore realized from the

study that most of these companies (about 95%) use

the manual system to manage their HR. These

companies include the Small and Medium

Enterprises (SMEs) and the limited guarantee

companies. A cursory look at figure 4 above

indicates that the private corporate enterprises

dominate in the organization type, followed by the

government organizations and SMEs in that order.

Though, the number of SMEs from the findings is

small, it must be emphasized that some of the

private corporate enterprises are registered as

corporate entities but have the characteristics of

SMEs, as portrayed in figure 4 above. It has, lucidly,

been established that about 90% of companies

registered in Ghana like most developing economies

are micro, small and medium enterprises (UNIDO,

1999; Aryeetey, 2001)

This was clearly confirmed by over half of the

firms which employ less than 100 employees as

depicted in figure 6. In Ghana, SMEs have been

recognized to be companies that employ less than

100 employees (Abor and Biekpe, 2009). Therefore,

the type of registered company and the staff strength

TheAdoptionandUseofHumanResourceInformationSystem(HRIS)inGhana

135

is very crucial having both positive and negative

effect on HRIS adoption. Profit making private

limited liability companies and firms with large staff

strength, for instance, could afford and would

purchase an information system to manage their HR

requirements. This is because these firms are large

and have the resources to afford such a system and

its maintenance. After all, it would not be proper or

useful to invest in such a system without ensuring

that its maintainability and usage will provide

owners sustainable competitive advantage.

On the contrary, most SMEs might not be in the

position to use an information system like HRIS,

from the study, due to size. This means the low

number of staff employed by SMEs might not

adequately satisfy the purpose for which such a

system may be implemented. Despite this, it is very

capital intensive to implement such a system which

the SMEs might not afford. Firm size has been

viewed as a determining factor of a firm’s capital

structure. Empirical evidence on the relationship

between size and capital structure of SMEs supports

a positive relationship (Sogorb-Mira, 2005). This

means, the larger the firm, the bigger the capital

structure and vice versa. Larger firms tend to be

more diversified and hence have lower variance of

earnings, making them able to tolerate high debt

ratios (Wald, 1999).

Like most developing economy, Ghanaian

industrial sector is dominated by the service sector,

followed by trade and commerce sector. It is

customary as a developing country to experience

low technological, telecommunication and

manufacturing sectors. The findings from the study

depicted that industry has no linkage to the tendency

to adopt HRIS in Ghana. The adoption rate does not

reveal any positive or negative influence on HRIS

adoption in the country.

However, the age of firms can impact positively

or negatively on HRIS adoption. From the figure 7

below, it could be seen that firms with over 11 years

experience tended to adopt HRIS compared with

those less in age. The relationship depicted by age

and adoption is crucial for successful HRIS

implementation. The age of the firm is a standard

measure of reputation (Abor and Biekpe, 2009). The

use of firm reputation is the good name a firm has

built over the years. This is important as it shows the

firms’ level of credibility and reputation in the

industry and or country. If organizations have passed

the test of time, then they are credible and so have

high adoption capabilities.

Though respondents attributed the low number

of staff as reason for not adopting an HRIS, it could

be seen from the above figure that many of them

have not yet adopted it as a result of ignorance of the

existence of the system and its importance or that

they were not just ready for such a system.. It is

interesting to note that some of these firms do not

even know about HRIS let alone to adopt it. In fact,

one of the respondents from the SMEs commented

that discussions were ongoing in the organization to

adopt such a system. Another stated that, they used

to have one in place which was given problems so

they never used it. They have, however, started

negotiations with the vendor for an improved one.

Though majority of 53% of the respondents

indicated that they were ready to adopt the use of

HRIS, a significant number of about 39% were not

ready. This high figure of non-readiness may be

attributed to the fact that, respondents may be

affirming their earlier response of low number of

employees as a reason for not adopting HRIS.

Again, this tells of the firms’ inability to acquire the

system due to higher implementation cost or their

ignorance of the importance of the system. Adopting

HRIS can be challenging as it can be costly and it

can take long periods of time before pre-adoption

benefits become reality after HRIS are fully

assimilated (Ashbaugh and Miranda, 2002). Actual

usage and adoption can lag by up to three years what

is available. This is supported by the fact that, even

those who believe they were ready to use such a

system, about one third of them were not sure or

aware of such a system and, therefore, had no plans

on when to implement one.

6 CONCLUSION

Using theories from the technological innovation

literature, this paper used quantitative data to

validate HRIS adoption in Ghanaian companies. Out

of the three contexts identified in the model,

organizational characteristics are of primary

importance in determining the decision to adopt

HRIS. Factors such as the size of firms, the type of

organization and the age of the organization are

more likely to influence adoption of HRIS.

Environmental factor, for example, industry type

have no direct effects on the decision to adopt HRIS.

Again, open-ended questions brought out

information to answer other factors including

technological characteristics like perceived cost

benefits trade off and organizational fit which also

affect HRIS adoption in Ghana. Other factors

including organizational competence and past IS

adoption could also be realized from these responses

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

136

to be other organizational factors which affect HRIS

adoption. It was also seen that most firms were not

ready to adopt HRIS due to cost of HRIS acquisition

or implementation and the low number of staff

especially for the SMEs. Apparently, most of the

SMEs have not adopted HRIS from the study

because of ignorance of the existence of the system

and its importance and therefore, had no plans of

implement one soon.

The results of this study have implications for

HRIS adoption in Ghana and other developing

countries. First, the study highlights the essentials of

HRIS adoption and its implication to developing

countries. Organizations that appreciate HRIS

adoption and are willing to invest limited resources

will be able to take advantage of the necessary

benefits of HRIS adoption including improved

organizational efficiency and effectiveness (Thong,

1999). It will assist managers to appreciate and

apply the potential benefits from the use of the HRIS

to all functional areas in HRM and also integrate it

to the core business of the organization. HRIS

adoption will also elucidate stakeholders including

the government to be aware of its potential

usefulness in order to formulate policies and

strategies that will encourage its adoption locally.

The study would enable researchers, practitioners

and professionals worldwide to have a fair

knowledge about opportunities and challenges

associated with the application of HRIS in firms in

developing economies like Ghana in order to advice

accordingly.

The usefulness of HRIS cannot be

overemphasized. Organizations can do well to adopt

it to gain sustainable competitive advantage in

whatever industries they find themselves. In using

this, it is important to identify all of HR functions

and develop the system to integrate these features

into the system for use. It is also relevant that the

system is designed in such a way as to be applied to

the core business of organizations. When this

happens, the system’s use will not only be optimal,

but also profitable to all stakeholders like customers,

suppliers, partners, users, owners, managements, etc.

Nonetheless, the following areas are suggested

for further research initiatives including:

• An empirical study of the extent of HRIS use of

HRIS in firms in developing countries

• The perception of users on outsourcing of HRIS

in organizations.

• HRIS adoption and use of HRIS in SMEs in

developing countries

• Challenges and benefits from the use of HRIS in

developing countries

REFERENCES

Abor, J. and Biekpe, N. (2009). How do we explain the

capital structure of SMEs in sub-Saharan Africa?:

Evidence from Ghana, Journal of Economic Studies,

Vol. 36 No 1, pp. 83–97

Absar M. M. N. and Mahmood M. (2011), “New HRM

Practices in the Public and Private Sector Industrial

Enterprises of Bangladesh: A Comparative

Assessment”, International Review of Business

Research Papers. Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 118-136.

Aryeetey, E. (2001), “Priority research issues relating to

regulation and competition in Ghana”, Working Paper

Series, Centre on Regulation and Competition,

Manchester.

Ashbaugh, S. and Miranda, R. (2002), “Technology for

human resources management: seven questions and

answers”, Public Personnel Management, Vol. 31

No.1, pp. 7-20.

Ball, K. S. (2001), “The use of human resource

information systems: a survey”, Personnel Review,

Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 677-93.

Blount, Y. and Castleman, T. (2009), “The curious case of

the missing employee in information systems

reserach”, Proceedings of the 20th Australasian.

CedarCrestone. (2005). “Workforce technologies and

service delivery approaches survey”, 8th Annual

Edition.

Chen, W. (2014), “A Framework for Human Resource

Information Systems Based on Data Streams”,

International Journal of Hybrid Information

Technology, Vol.7, No.3, pp.177-186

Dedrick, J. and West, J. (2004), “An exploratory study

into open source platform adoption”, Proceedings of

the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences, IEEE, Big Island, HI, USA.

DePietro, R., Wiarda, E. and Fleischer, M. (1990), “The

context for change: organization, technology and

environment”, in Tornatzky, L.G. and Fleischer, M.

(Eds), The Process of Technological Innovation,

Lexington Books, Lexington, MA, pp. 151-75.

Dessler G. (2011), Human resource management 12

th

ed.,

Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Fichman, R. G. (2004), “Going beyond the dominant

paradigm for information technology innovation

research”, Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, Vol. 5 No. 8, pp. 314-55.

Gueutal H. G. and Stone D. L. (2005), The Brave New

World of e-HR, Jossey-Bass,San Francisco.

Henriksen, H. Z. and Mahnke, V. (2005), “E-procurement

adoption in the Danish public sector”, Scandinavian

Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 85-

106.

Hendrickson A.R. (2003). Human Resources Information

Systems: Backbone Technology of Contemporary

Human Resources. Journal of Labor Research. 24(3):

382-394.

Jeyaraj, A., Rottman, J. and Lacity, M. (2006), “A review

of the predictors, linkages and biases in IT innovation

TheAdoptionandUseofHumanResourceInformationSystem(HRIS)inGhana

137

adoption research”, Journal of Information

Technology, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 1-23.

Kuan, K. K. Y. and Chau, P. Y. K. (2001), “A perception-

model for EDI adoption in small business using a

technology-organization-environment framework”,

Information and Management, Vol. 38 No. 8, pp. 507-

12.

Kumar et al., (2013), “The human resource information

system: a rapid appraisal of Pakistan’s capacity to

employ the tool”, BMC Medical Informatics and

Decision Making, Vol. 13 No. 104,

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/13/104

Lippert, S. K. and Swiercz, P. M. (2005), “Human

resource information systems (HRIS) and technology

trust”, Journal of Information Science, Vol. 31 No. 5,

pp. 340-53.

Mishra A. and Akman I. (2010). Information Technology

in Human Resource Management: An Empirical

Assessment. Public Personnel Management. Vol. 39

No. 3: pp. 243-262.

Palvia, P. C., Palvia, S. C. J. and Whitworth J. E. (2002),

“Global information technology: a meta analysis of

key issues”, Information& Management Vol. 39, pp.

403–414.

Pierce, J. L., and Delbecq, A. L. (1977), Organizational

structure, individual attitudes and innovation,

Academy of Management Review, Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 27-

37.

Rangriz H., Mehrabi J and Azadegan A. (2011). The

Impact of Human Resource Information System on

Strategic Decisions in Iran. Computer and Information

Science. Vol. 4 No. 2 pp. 81-87.

Rogers, ü. M. (1983), Diffusion of Innovations, 3d ed.

New York: Free Press.

Ruël, H. J. M., Bondarouk, T. and Van der Velde, M.

(2007), “The Contribution of e-HRM to HRM

Effectiveness”, Employee Relations, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp.

280–291.

Saleem, I. et al., (2011), “Role of Information and

Communicational Technologies in perceived

Organizational Performance: An Empirical Evidence

from Higher Education Sector of Pakistan”, Business

Review. Vol. 6 No. 1 pp. 81-93.

Sateem I. (2012), Impact of adopting HRIS on three tiers

of HRM: Evidence from Developing Economy,

University of Central Punjab, Lahore, Vol. 7 No. 2

Shani A. and Tesone D. V. (2010), “Have human resource

information systems evolved into intemal e-

commerce?” Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism

Themes. Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 30-48.

Shrivastava, S. and Shaw, J. B. (2004), “Liberating HR

through technology”, Human Resource Management,

Vol. 42 No. 3, pp. 201-222.

Sogorb-Mira, F. and How, S. M. E. (2005), “Uniqueness

affects capital structure: evidence from a 1994-1998

Spanish data panel”, Small Business Economics, Vol.

25 No. 5, pp. 447-57.

Stanton, J. M. and Coovert, M. D. (2004),“Turbulent

waters: The intersection of information technology

and human resources”,Human Resource Management,

Vol. 43 No. 2, pp. 121−125.

Strohmeier, S. (2007), “Research in e-HRM: Review and

Implications”, Human Resource Management Review,

Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 19-37.

Strohmeier, S. and Kabst R. (2009), “Organizational

adoption of e-HRM in Europe: An empirical

exploration of major adoption factors”, Journal of

Managerial Psychology, Vol. 24 No. 6.

Teo, T. (2007), “Organizational characteristics, modes of

internet adoption and their impact: a Singapore

perspective”, Journal of Global Information

Management, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 91-117.

Thompson, V.A. (1969), Bureaucracy and Innovation.

Huntsville: University of Alabama Press.

Thong J. Y. L, (1999), An Integrated Model of

Information Systems Adoption in Small Businesses.

Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 15,

No. 4 pp. 187-214

Tornatzky, L. and Fleischer, M. (1990), The Processes of

Technological Innovation, Lexington Books,New

York, NY.

Tornatzky, L.G. and Klein, K.J. (1982), “Innovation

characteristics and innovation adoption

implementation: a meta-analysis of findings”, IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. EM-

29 No. 1, pp. 28-45.

Townsend, A. M. and Bennett, J. T. (2003),“Human

resources and information technology”,Journal of

Labor Research, Vol. 24 No. 3, pp. 361−363.

Troshani, I., Jerram, C. and Gerrard, M. (2010), Exploring

the organizational adoption of human resources

information systems (HRIS) in the Australian public

sector, Proceedings of the 21st Australasian

Conference on Information Systems (ACIS2010),

Brisbane, Australia.

Troshani I., Jerram C. and Hill S.R. (2011). Exploring the

public sector adoption of HRIS. Industrial

Management & Data Systems. Vol. 111 No. 3 pp. 470

– 488.

UNIDO, (1999) SMEs in Africa Survive against all Odds,

http://www.unido.org/doc/view?document_id=3927&l

anguage_code=en.

Viswesvaran, C. (2003), “Introduction to special issue:

Role of technology in shaping the future of staffing

and assessment”, International Journal of Selection

and Assessment, Vol. 11 No. 2-3, pp. 107−112.

Wald, J. K. (1999), “How firm characteristics affect

capital structure: an international comparison”,

Journal of Financial Research, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp.

161-87.

Wilson-Evered, E. and Härtel, C. E. J. (2009). Measuring

attitudes to HRIS implementation: a field study to

inform implementation methodology. Asia Pacific

Journal of Human Resources, Volume 47, Issue 3, pp.

374–384.

Yusoff, Y., Ramayah T. and Ibrahim H. (2010), E-HRM:

A proposed model based on technology acceptance

model, School of Management, University Sains

Penang, Malaysia.

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

138