Individual and Contextual Antecedents of Knowledge Acquisition

Capability in Joint ICT Project Teams in Malaysia

Adedapo Oluwaseyi Ojo and Murali Raman

Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Keywords: Absorptive Capacity, Individual Differences, Knowledge Acquisition Capability, Joint ICT Project Team,

Partner’s Support, Malaysia, Micro Antecedents.

Abstract: This study investigates the significance of joint ICT projects with foreign partners in the acquisition of

knowledge by local personnel in an emerging economy, based on the perspective of individual’s absorptive

capacity (i.e., ACAP). The model conceptualizes knowledge acquisition capability as the individual

dimension of ACAP and posits differences in prior experience and learning orientation as well as

individual’s perception of partner’s support as antecedents to local employees’ abilities to (i) recognize the

value of and (ii) assimilate foreign partners’ embedded knowledge. This model was validated by the results

of the structural equation modelling, conducted on a cross sectional survey of 205 local team members of

joint ICT projects in Malaysia. All the hypothesized relationships were supported, with the exception of that

between prior experience and ability to recognize the value of knowledge as well as learning orientation and

ability to assimilate knowledge. Accordingly, the theoretical and practical implications of the findings were

expatiated, with suggestions offered on the areas for future research.

1 INTRODUCTION

In support of the national drive towards attaining the

knowledge based economy, the Malaysian

Government has acknowledged technology parks as

platform to facilitate the engagement of world’s

leading firms in the local economy. One of the major

milestones was the establishment of the multimedia

super corridor (MSC) in 1996. The MSC was

inaugurated in order to advance the country to the

cutting-edge of the bourgeoning information and

communications technology (ICT) industry. The

MSC has succeeded in attracting multinational

corporations (MNCs) and international joint

ventures, thereby facilitating the growth of local ICT

talents and firms, through access to foreign

knowledge and expertise. The knowledge inflow has

been associated with institutional and policy

intervention (Ramasamy et al., 2004), inter-firm

interaction (Richardson et al., 2012; Malairaja and

Zawdie, 2004), as well as firm and employees

characteristics (Awang et al., 2013).

Absorptive capacity (ACAP) is one of the most

significant characteristics of a firm with a

constraining impact on the acquisition of external

knowledge (Lyles and Salk, 1996; Lane et al., 2001;

Raman et al., 2014). Based on R&D activities, an

organisation builds internal capability, as the

employees gain exposure and insight to new

concepts, and incorporate the learning into the firm’s

activities, thereby expanding the knowledge bases

(Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). In essence, by sharing

experience and learning, the personnel facilitates

both the individual and collective capacity to

respond to changes. Therefore, both the individual

members and the context of their engagement are

critical to the firm’s ACAP. However, extant studies

have overlooked the underlying role of individuals,

but ACAP has repeatedly been associated with the

organisational and dyadic antecedents (Lane and

Lubatkin, 1998; Jansen et al., 2005). Consequently

firm’s heterogeneity have been isolated from

differences at the individual level, thereby

dissociating organisational level outcome from the

underlying choice and actions of the members

(Volberda et al., 2010; Felin et al., 2012).

Despite the recent studies hypothesizing

individual level antecedents as prior experience

(Lane et al., 2006; Minbaeva et al., 2003; Zhao and

Anand, 2009), cognition (Zahra and George, 2002),

and task motivation (Silva and Davis, 2011; Ojo and

Raman, 2015), limited attempts have been offered to

70

Ojo, A. and Raman, M..

Individual and Contextual Antecedents of Knowledge Acquisition Capability in Joint ICT Project Teams in Malaysia.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 70-78

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

empirically clarify these antecedents. Specifically,

the effects of individual differences on the

associated dimensions of ACAP have been

overlooked, while data have mostly originated from

single respondent or proxy measures used to infer

individual differences. Consistent with the dynamic

capability perspective, clear delineation of the

individual characteristics and interaction pertinent to

learning capabilities could offer clarification on the

path to strategic renewal (Teece, 2012). Therefore,

further to the extant emphasis on organisational

mechanisms, individual difference is another

important building block to organisational change.

Given the above, the present study investigates

the underlying differences and the implication of the

context of engagement on individual’s ACAP. The

context is the asymmetrical joint project teams, set

up to facilitate the transfer of knowledge from

expatriate to local employees in the Malaysian ICT

industry. In line with recent conceptualization on

micro-antecedents, we argued that the local team

members of the joint project teams must demonstrate

the right aptitude and disposition, in order to acquire

the foreign knowledge. The next section presents the

theoretical background for our propositions, after

which the research method is explained. This

encompasses sub-sections on the sample and

procedure, measurements, as well as analysis and

results. Furthermore, we discuss the theoretical and

practical implications of our findings. Thereafter the

concluding section considers the limitations of the

present study and offers relevant suggestions for

future research.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

From the individual level perspective, ACAP can be

considered as the capacity to learn or acquire

knowledge (van den Bosch et al., 2003). Thus, an

organisation learns through the individual members,

who acquire knowledge by interacting and sharing

experience with others (von Krogh et al., 1994;

Crossan et al., 1999). Organisational knowledge can

be embedded in people, routines, processes, tasks or

tools, nevertheless, people’s ability in adapting

knowledge across different context is exceptional

and unique (Argote et al., 2003). Although, the

management can coordinate knowledge transfer by

motivating the local personnel, and also facilitate the

organisational processes to support strategic renewal

(Lyles and Salk, 1996), nevertheless, without the

personnel demonstrating the learning capability, the

acquisition of partner’s knowledge is unrealistic. To

this end, the learner’s knowledge receptive

capability, i.e. ACAP has been established as the key

determinant to learning in joint project teams

(Inkpen, 2008).

The present study explicates the role of

individuals in ACAP, in particular, within the

context asymmetric project team, set up to facilitate

knowledge transfer. The external knowledge is the

expertise possessed by the expatriate, but accessible

to the local employees through their engagement in

the joint project teams. Theorists have mainly

ascribed individual differences to dispositions

towards thinking, goals, values or beliefs (Lubinski,

2000; Schmitt et al., 2003). Therefore, we posit that

the knowledge acquisition capability, i.e. ACAP is a

function of the variation in individual’s experience,

disposition to learning. Furthermore, we hypothesize

the effect of the context of their engagement in terms

of partner support on the local personnel’s ACAP.

The above proposition is premised on the notion

that individual ACAP constitutes one of the building

blocks to organisational ACAP (Zahra and George,

2002; Raman et al., 2014). Thus, consistent with

Zahra and George’s (2002) theoretical exposition of

potential ACAP as an individual level capability, we

consider the two associated dimensions. First is the

ability to recognize the value of partner knowledge,

which is operationalized as the individual capability

to search, identify, and accurately evaluate the worth

of the knowledge (Ojo et al., 2014). The second

dimension is the ability to assimilate knowledge,

which is the individual capability to learn, interpret

and develop a deep understanding on valuable

knowledge (Nemanich et al., 2010). The subsequent

subsections examine the underlying hypotheses for

the above proposition.

2.1 Prior Experience

Cohen and Levinthal (1990) emphasize the

cumulative impact of learning, whereby individual’s

earlier learning influences the ability to learn new

things. Prior experience has corresponding effect on

the locus and extent of search for external

knowledge (Lane et al., 2006). Seeley and Targett

(1999) found that individual’s knowledge in a given

task diminishes as he/she engages less in updating

his/her knowledge about the task. Van Riel and

Lievens (2004) found that experienced marketing

researchers possess higher capability to interpret and

assimilate emerging market trend and incorporate

such into the design of new offerings. Based on a

Individual and Contextual Antecedents of Knowledge Acquisition Capability in Joint ICT Project Teams in Malaysia

71

sample of 208 engineers, Deng et al. (2008)

established the positive impact of prior engagement

in problem solving on innovative capability. Based

on prior experience, individuals accumulate

knowledge in the memory, which enable them to

recognize and assimilate related external knowledge.

Thus, employees with related knowledge as that

embedded in foreign partner are hypothesized to

possess the ability to access the partner’s valuable

knowledge as well as target it for assimilation. To

this end, the following hypotheses are put forward:

H1a. Prior experience in related knowledge is

positively associated with the ability of an

individual to recognize the value of foreign

partner knowledge in a joint project team.

H1b. Prior experience in related knowledge is

positively associated with the ability of an

individual to assimilate foreign partner

knowledge in a joint project team.

2.2. Learning Orientation

This is the strong disposition towards improving

competence by developing new skills and taking up

challenging tasks (Bell and Kozlowski, 2002). By

taking learning as personal responsibility, an

individual inclination is towards acquiring new

knowledge underlying the development of

competence (Hansen, 1999). Proactive minded

individuals are well disposed and attentive to others’

experience, as well as understanding and

interpretation on given concept (Ayas, 1998;

Hansen, 1999). Thereby strong orientation towards

learning could impact on the willingness to put in

the extra effort needed to acquire complex skills and

improve the knowledge based (Bell and Kozlowski,

2002; Laursen and Salter, 2006). Empirical research

on absorptive capacity within the R&D domain

(Howell and Shea, 2001) found the positive impact

of individual search effort on the identification of

valuable external knowledge. Also, Yeh (2008)

investigation on middle level engineers, confirmed

self-initiated learning as antecedent for performance.

Thus, the following hypotheses are suggested.

H2a. Learning orientation is positively

associated with the ability of an individual

to recognize the value of foreign partner’s

knowledge in a joint project team.

H2b. Learning orientation is positively

associated with the ability of an individual

to assimilate foreign partner’s knowledge

in a joint project team.

2.3 Partner’s Support

Given the competence gap between the partners, the

acquisition of knowledge by the local personnel

could be facilitated through the technical support

provided by the foreign partners. Scholars (Lane et

al., 2001; Lyles and Salk, 1996) have demonstrated

the provision of training and technological

assistance, as the support mechanisms relevant in

enabling technological acquisition in joint ventures.

The acquired knowledge is easily institutionalized,

when the transferor becomes actively engaged in

supporting the acquirer to adapt it within the specific

context (Steensma and Lyles, 2000; Kasuga, 2003).

For instance, the expatriate could support the local

employees to acquire related understanding on the

specific practices, thereby enabling the latter to

assimilate the knowledge (Inkpen, 2008; Dyer and

Nobeoka, 2000). Dhanaraj et al. (2004) assert that as

interactions deepen between partners the

collaboration becomes seamless. This is consistent

with Inkpen’s (2008) findings on the strategic

alliance between GM and Toyota. The lack of

support by the grafted managers, contributed in

GM’s initial inability to appreciate the value of

Toyota Production Systems (TPS). In addition, the

empirical significance of organisational support has

been demonstrated in the transfer knowledge to new

hires or trainee employees (Simosi, 2012). Thus, in

line with the above, we hypothesize that;

H3a. Individual’s perception of foreign partner

support is positively associated with the

ability of an individual to recognize the

value of partner’s knowledge in a joint

project team.

H3b. Individual’s perception of foreign partner

support is positively associated with the

ability of an individual to assimilate

partner’s knowledge in a joint project team.

2.4 Individual Absorptive Capacity

The individual members of the firm play the

significant role of absorbing knowledge from the

external sources. Zahra and George (2002) argued

that an organisation needs to first acquire and

assimilate external knowledge before effort could be

concentrated towards the exploitation of such

knowledge. To this end, they delineate ACAP into

potential and realized components corresponding to

individual and collective levels, respectively. The

latter is dominant at the individual level and

expressed as the abilities to (i) recognize the value of

and (ii) assimilate external knowledge. Thus,

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

72

individuals are not just resources possessed by the

firm, but enabler of the process for the firm’s

transformation, i.e., through the acquisition of

external knowledge. Proponents of innovation

theory have acknowledged the significant role of

individuals in learning from firm activities (Nelson

and Winter, 1977; Allen, 1977). For instance R&D

activities can be considered as firm’s investment in

building employees’ capability to search for internal

technological and organisational knowledge.

An individual’s ability to assimilate external

knowledge is conditioned on his/her ability to

recognize how such knowledge relates to the

cognitive map already stored in the memory

(Todorova and Durisin, 2007). The cognitive map is

the pattern of association that impacts an

individual’s search for and categorization of new

information (Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000). This map

enables an individual to exert the knowledge search

effort on an area with the most significant value to

the assigned task. Thus, the aptitude of an individual

in recognizing the value of knowledge can be

associated with efficient search effort, which in turn

can facilitate his/her commitment to understand the

specific valuable knowledge (Lettl et al., 2008). The

investigation of Nemanich et al. (2010) on U.S.-

based research teams supported the positive

relationship between the ability of the team member

to evaluate external knowledge and the ability to

assimilate the knowledge.

H4. Individual’s ability to recognize the value

of foreign partner’s knowledge is positively

associated with the ability to assimilate the

knowledge in a joint project team.

3 METHOD

3.1 Sample and Procedure

A random sample of local ICT professionals

engaged in joint projects with expatriates was

selected across 62 joint ventures on the list of active

MSC-status companies. To facilitate the data

collection, human resource (HR) personnel in each

firm was designated as contact persons. The contact

persons were requested to randomly select ICT

project teams constituted by the local personnel and

expatriates in their respective firms, and to

administer the questionnaires on the former. They

were specifically instructed to select two to three

local personnel who were directly attached with the

expatriates from each of the identified project team.

Out of a total of 390 questionnaires sent out, 205

valid responses were returned, corresponding to an

overall response rate of 52.6 percent. In order to

ascertain the absence of non-response bias, we

obtained the demographic profiles for the non-

respondents from the contact person. Accordingly,

series of χ2 and t test were computed to compare the

respondents (n= 205) with those who had not

completed the questionnaires (n= 185). Based on the

outcomes, responses were found not to be selective

for age, education level, work experience, joint team

tenure, as well as job position (p > 0.05).

The demographic profiles of the respondents are

presented as follow. More than 81 percent of the

respondents were above the age of 26 years, and

73.1 percent had at least a bachelor degree.

Moreover, 67.8 per cent of the respondents had

acquired professional experience of at least four

years, while two-thirds of the respondents had been

engaged in at least two joint project teams. In terms

of job positions, almost half of the respondents (49.8

percent) were system analysts, while 17.5 per cent

were project managers. Programmers and system

designers made up 16.2 and 12.4 percent of the total

respondents, respectively, and the remaining 4.1

percent accounted for other positions, such as testers

and technical support.

3.2 Measurements

All the constructs were measured with scales

adapted from extant literature, and the assessment

based on the five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1

= strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). We

conducted the pilot testing for the initial

questionnaire, with a sample of 35 respondents

selected from across the joint ventures ICT firms on

the list of active MCS-status companies. These

respondents were excluded from the final survey.

The majority of the respondents (i.e. 55%) are

within the age group of 26 – 35 years, followed by

those within 36 – 45 years (i.e.19%). More than 68%

had at least a bachelor degree and about 70% had

acquired professional experience of at least four

years. Moreover, 75% of the respondents have been

engaged in at least 2 joint project teams and 55% of

them are system analyst. Based on their comments

and statistical assessment, some of the questions

were rephrased to improve clarity and content

validity. In addition, we ensured that the anonymity

of the respondents were preserved, as promised in

the enclosed cover letter, thereby minimizing the

effects of social desirability and biasness associated

with self-reported survey.

Individual and Contextual Antecedents of Knowledge Acquisition Capability in Joint ICT Project Teams in Malaysia

73

Prior experience was operationalized as the

quantity of the accumulated knowledge that is

related to the new external knowledge (Cohen and

Levinthal, 1990). Thus, respondents were asked to

assess the extent to which they agree with five (5)

statements describing the level of their possessed

general and theoretical knowledge (Gimeno et al.,

1997), training, work experience and expertise

(Cooper et al., 1994; Huber, 1991) on the project.

The Cronbach’s alpha for this construct was 0.91.

Learning orientation was operationalized as the

disposition to ask mastery and measured with five

adopted from VandeWalle (1997). The Cronbach’s

alpha for the constructs was 0.92.

The measurement scale for partner’s support

consists of three items obtained from inter-firm

knowledge transfer literature (Lyles and Salk, 1996;

Lane et al., 2001; Minbaeva et al., 2003). These

items assess the extent to which the foreign

employees are accessible and helpful, and actively

participated in the joint project.

The ability to recognize the value of partner’s

knowledge was operationalized as the capability to

accurately evaluate the worth of knowledge and the

ability to assimilate partner’s knowledge was

operationalized as the capability to learn, interpret,

and develop a deep understanding of valuable

knowledge (Nemanich et al., 2010; Ojo et al., 2014).

Both were measured by two different sets of four

items. Specifically, the respondents were asked to

assess the extent to which they agree with certain

statements that describe their engagement in joint

project teams. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 and

0.88 for the ability to recognize and the ability to

assimilate partner’s knowledge, respectively.

3.3 Analysis and Results

In order to ascertain the non-significance of common

method variance, the Harman’s one-factor test was

conducted (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). The

outcome from the single un-rotated EFA on all the

constructs revealed the absence of common factor.

The largest factor accounted for 32.71% of the total

74.70% variance explained by all the five factors,

with eigenvalues greater than 1.00. Consequently,

the overall measurement model for the five

constructs was evaluated in a single CFA procedure

(Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). All the items loaded

on their specified factors. The composite reliability

(CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values

were computed from the CFA loadings. As shown in

Table 1, the AVE and CR values are above the cut-

off criterion of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) and

0.7 (Hair et al., 2010), respectively. Thus,

convergent validity was demonstrated for all of the

constructs.

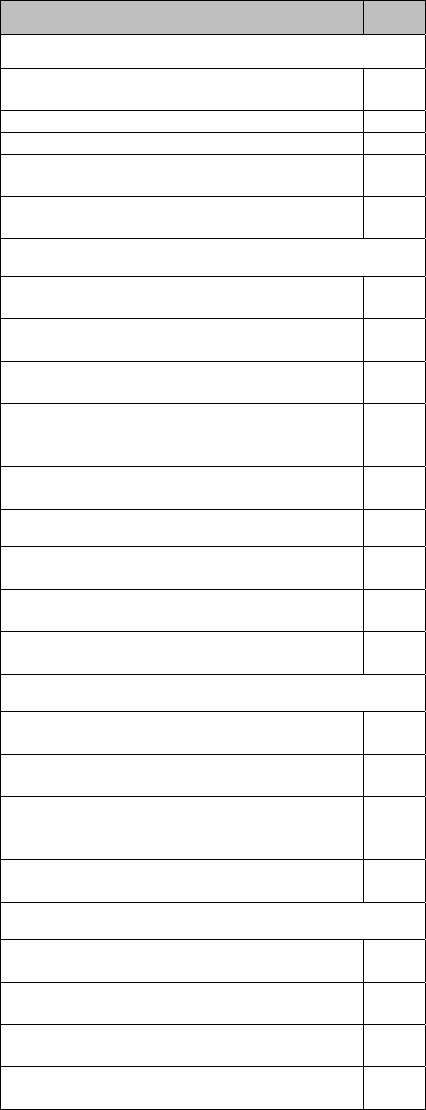

Table 1: Measurement Scales and Standardized CFA

Estimates.

Constructs and items Std. Est

.

Prior Experience (CR = 0.91; AVE = 0.68)

I had the required general knowledge on the

project.

.806

I had acquired substantial theoretical knowledge. .852

I had attended extensive training in related area. .811

I had substantial working experience in related

area.

.847

I had acquired some level of ex

p

ertise in related

area.

.731

Learning Orientation (CR = 0.92, AVE=0.69)

I am willing to pursue challenging tasks from

which I can learn new things.

.756

I often look for opportunities to develop new

skills and knowledge.

.797

I prefer taking up challenging and difficult tasks

at work from which I can learn new skills.

.913

I am willing to put in extra effort where

necessary to develop new skills and enhance my

knowledge.

.872

I prefer to work in environments that require a

high level of ability and talent.

.796

Partner’s Support (CR=0.87, AVE=0.69)

I received adequate technical support from the

foreign partner

.654

I received relevant training from the foreign

partner

.745

I received timely and helpful assistance from

foreign partner

.895

Ability to Recognize (CR = 0.88, AVE=0.64)

I was able to develop awareness on partner’s

knowledge.

.842

I was able to keep track of partner’s knowledge,

by consulting other sources of information.

.833

I was able to identify partner’s knowledge with

the most significant value to the project

performance.

.827

I was capable at accurately evaluating the worth

of partner’s knowledge in the project.

.691

Ability to Assimilate (CR = 0.89, AVE=0.66)

I was able to learn the use of partner’s

knowledge.

.801

I was capable at understanding the knowledge

associated with project.

.850

I was adept at interpreting the use of the

knowledge associated with the project.

.845

I tried to experiment with the knowledge

associated with the project.

.748

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

74

Sequel to the above, the structural model was

evaluated by replacing the covariance paths (i.e.

double edged arrows) associated with the

endogenous variable with the hypothesized

structural paths (i.e. single edged arrows). The

selected goodness-of-fit indices from the AMOS 18

package revealed a good fit to data (i.e. χ2 = 127.765

/ p=.390; RMSEA = .011 / p-close = 1.000; CFI =

.997, TLI = .997). Specifically, the value of p for the

χ2 was not significant, i.e., > 0.05, thus the model

can be regarded as acceptable (Bagozzi and Yi,

2012). As a result, the model was employed in

testing the hypothesized effects.

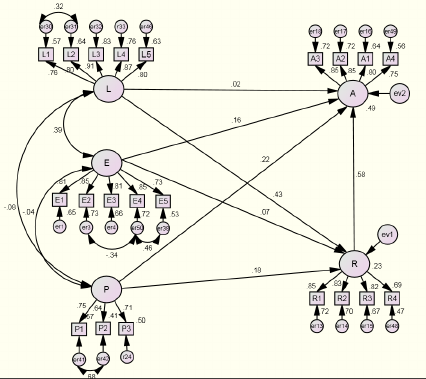

As shown in Figure 1, the relationship between

prior experience (E) and the ability to assimilate

knowledge (A) was significant (β= .16, p < .05),

however, the relationship between the former and

ability to recognize the value of knowledge (R) was

not significant. Thus, H1b was supported, but H1a

was not supported. The path from learning

orientation (L) to ability to recognize the value of

knowledge was significant (β= .43, p < .001), but the

path to ability to assimilate knowledge was not.

Thus, H2a was supported, but H2b was not

supported. Furthermore, both H3a and H3b were

supported, with a significant path obtained from

partner’s support (P) to ability to recognize the value

of knowledge (β= .18, p < .05) and ability to

assimilate knowledge (β= .22, p < .01), respectively.

Finally, the individual’s ability to recognize the

value of knowledge was determined to be

significantly related to the ability to assimilate

knowledge (β= .58, p < .001). Thus, H4 was

supported.

Figure 1: Standardized Path Estimates.

4 DISCUSSION

The present study advances the dynamic capability

perspective to develop a model which demonstrates

the role of team members and the context of their

engagement in strategic renewal, thereby suggesting

individual differences as another antecedent of

learning, in addition to the widely acknowledged

organisational and environment factors (Teece,

2012). Specifically, the current study investigates

the pertinent antecedents of the individual ACAP,

thus contributing to extant literature in several

aspects.

Further to the theoretical notion on the existence

of potential ACAP at the individual level (Zahra and

George, 2002) this study empirically validates its

pertinent dimensions, i.e. ability to recognize the

value of and ability to assimilate foreign partner’s

knowledge. As revealed in this study, individuals

that have recognized the value of foreign partner’s

knowledge in their assigned task are able to develop

better understanding on the relevance of such

knowledge in the joint project team. Thus, the

recognition of the value of knowledge can facilitate

deeper assimilation, in that the effort could be fully

channelled toward uncovering the underlying

knowledge bases.

Our findings corroborate the varying effect of

prior experience on ACAP (Cohen and Levinthal,

1990; Minbaeva et al., 2003). We found that the

prior experience acquired by an individual in an area

related to the joint ICT project could impact on his /

her ability to assimilate the partner’s knowledge (i.e.

H1b). Surprisingly, the former was determined not

to be associated with the ability to recognize the

value of partner’s knowledge (i.e. H1a). Even

though this challenges the theoretical notion on

ACAP, yet, it conforms to Lane and Lubatkin’s

(1998) findings – firm’s engagement in R&D (i.e.,

knowledge acquisition) was not related to the

variance of ACAP. This outcome is also in line with

the path dependence nature of learning. Individual’s

understanding could deepen with the possession of

prior related knowledge, but this might have little or

no appreciable impact on his/her ability to recognize

the value of knowledge. According to Cohen and

Levinthal (1990) an individual’s mental model

accumulated in the memory evolves along the path

of his/her exposure. Therefore, unless concerted

effort is channelled toward exploring new things, an

individual’s interpretation of future phenomena

could be limited by the mental model.

Moreover, individual’s learning orientation was

significantly associated with the ability to recognize

Individual and Contextual Antecedents of Knowledge Acquisition Capability in Joint ICT Project Teams in Malaysia

75

the value of knowledge, i.e., H2a, but not ability to

assimilate knowledge, i.e. H2b. This reinforces the

complementary nature of prior related knowledge

and learning disposition (Cohen and Levinthal

1990). Except concerted effort is exerted to

exploring new things, individual’s interpretation of

new concept could be limited by the mental model

already registered in the memory. Crossan et al.

(1999) revealed that the ability to recognize new

knowledge is conditioned on the recognition of a

similar pattern in the memory. Learning-oriented

people are opened to experiencing new things (Brett

and VandeWalle, 1999) and self-directed (Yeh,

2008). Thus, they are more likely to break barriers

and cross boundaries in their drive towards task

mastery, especially when they perceive their skill set

as inadequate. As a result, their disposition is suited

to putting in the necessary effort towards uncovering

patterns related to that already stored in the memory,

thereby facilitating the recognition of the value of

new knowledge.

As hypothesized, foreign partner’s support was

determined to be associated with both ability to

recognize the value of knowledge and ability to

assimilate knowledge. Given the asymmetric nature

of the joint project, knowledge acquisition by the

local team members could be fast tracked when the

foreign partners facilitate the adaption and

dissemination of the embedded knowledge to the

former. The target knowledge is tacit and embedded

in practice so that team member interactions can

enable stronger ties and the sharing of experience

and perspective. By providing adequate support to

and engaging actively with the local partner, the

foreign partner can deepen the strength of social ties

within the joint project team (Uzzi & Lancaster,

2003). Thus, the extent of support provided by the

expatriates grafted into the joint project team, as

perceived by the local members, could impact the

acquisition of knowledge.

Our findings have implications for the

management of joint ICT project teams in Malaysia.

It is essential that the managerial and leadership

drive for the upgrade of local capability through the

acquisition of competent partners’ knowledge be

supported with the engagement of personnel with the

underlying learning capabilities. In addition to the

organisational norm of recruiting experienced

personnel, the management should also consider

their disposition to learning. The ability to

recognize the value of new knowledge requires the

commitment of effort towards uncovering patterns

related to that already stored in the memory.

Therefore, individual learning disposition

complements prior related experience in order to

facilitate the recognition and assimilation of new

knowledge. With respect to the significance of

foreign partner’s support, the local partner should

ensure that the contractual agreement with the

former explicitly state the level of support to be

provided to the local team members. By ensuring

supportive collaboration, the local team members of

the joint project teams could be enabled to identify

and assimilate the knowledge embedded in the

foreign partner. This could enable them to develop

close relationship with and be connected enough to

the expatriates to seek clarification, when relevant,

without fear of rejection. Basically, when the

expatriates are perceived as helpful, the local

members are better disposed to approach them for

assistance. Likewise, the former will take proactive

measures to facilitate problem resolution.

Furthermore, the ability to assimilate knowledge

requires the development of deeper insight, which is

evident in the mastery of procedures / methods

underlying the task.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study advances the micro-level perspective of

ACAP, by demonstrating the effects of individual

differences and the context of their engagement on

knowledge acquisition capability. Thus, further to

the clarification of the role of individuals in the

acquisition of knowledge from joint project teams,

this study also offers opportunities for further

research. Future studies should attempt to clarify the

effects of other antecedents on both the individual

and collective components of ACAP. There is also

need for study to investigate the mechanisms

through which individual components are linked to

the collective components. The impact of cultural

differences on ACAP within joint project is another

important area for future studies. Furthermore,

subsequent studies are expected to address some of

the limitations of this study. The use of longitudinal

design is recommended, so as to capture the

underlying temporal and causal effects of ACAP.

Also, the attendant weakness of the self-reported

survey could be minimized by incorporating data

from other sources. For example, future studies

should consider the perspective of the foreign team

members on the ACAP dimensions. Finally, the

validated model should be extended to other

contexts, in order to ascertain the generalization of

the findings.

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

76

REFERENCES

Allen, T. J. (1977). Managing the Flow of Technology.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Argote, L., McEvily, B. and Reagans, R. (2003).

Managing knowledge in organisations: an integrative

framework and review of emerging themes.

Management Science, 49(4), 571-582.

Anderson, J. C. and Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural

equation modeling in practice: A review and

recommended two stage approach. Psychological

Bulletin 27(1), 5-24.

Awang, A. H., Hussain, M. Y. and Malek, J. A. (2013).

Knowledge transfer and the role of local absorptive

capability at science and technology parks. The

Learning Organisation, 20(4/5), 291-307.

Ayas, K. (1998). Learning through projects: meeting the

implementation challenge. In R., Lundin and C.

Midler (Eds.), Projects as arenas for renewal and

learning processes (pp. 89-98). USA: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Bagozzi, R. P. and Yi, Y. (2012). Specification,

evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation

models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

40(1), 8-34.

Bell, B. S., and Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2002). Goal

orientation and ability: Interactive effects on self-

efficacy, performance, and knowledge. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 87(3), 497–505.

Brett, J. F. and VandeWalle, D. (1999). Goal orientation

and specific goal content as predictors of performance

in a training program. Journal of Applied Psychology,

84(6), 863–873.

Cohen, W. M., and Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive

Capacity: A new perspective on learning and

innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1)

128-152.

Cooper, A. C., Gimeno-Gascon, F. J., and Woo, C. Y.

(1994). Initial human and financial capital as

predictors of new venture performance. Journal of

Business Venturing, 9(5), 371-395.

Crossan, M., Lane, H., and White, R. (1999). An

organisational learning framework: From intuition to

institution. Academy of Management Review, 24, 522-

538.

Deng, X., Doll, W. J., and Cao, M. (2008). Exploring the

absorptive capacity to innovation/ productivity link for

individual engineers engaged in IT enabled work.

Information and Management, 45, 75-87.

Dhanaraj, C., Lyles, M. A., Steensma, H. K., & Tihanyi,

L. (2004). Managing tacit and explicit knowledge

transfer in IJVs: The role of relational embeddedness

and the impact on performance. Journal of

International Business Studies, 35(5), 428-442.

Dyer, J.H. and Nobeoka, K. (2000), “Creating and

managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing

network: The Toyota case”, Strategic Management

Journal, 21(3), 345-367.

Felin, T., Foss, N.J., Heimeriks, K.H. and Madsen, T.L.

(2012). Microfoundations of routines and capabilities:

individual processes and structure. Journal of

Management Studies, 49(8), 1351-1374.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural

equation models with unobservable variables and

measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research,

18, 39-50.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., and Woo, C. Y.

(1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human

capital and the persistence of underperforming firms.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750-783.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R.

E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global

Perspective (7th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education

Inc.

Hansen, M. (1999). The search-transfer problem: The role

of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organisation

subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 82–

111. 178).

Howell, J. M. and Shea, C. M. (2001). Individual

differences, environmental scanning, innovation

framing, and champion behaviour: Key predictors of

project performance. The Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 18, 15–27.

Huber, G. P. (1991). Organisational learning: The

contributing processes and the literature. Organisation

Science, 2, 88–115.

Inkpen, A. C. (2008). Knowledge transfer and internatio-nal

joint ventures: The case of NUMMI and General

Motors. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4), 447-453.

Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., and Volberda, H.

W. (2005). Managing potential and realized absorptive

capacity: How do organisational antecedents matter?

Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 999-1015.

Kasuga, H. (2003). Capital market imperfections and

forms of foreign operations, International Journal of

Industrial Organization, 21, 1043–1064.

Lane, P. J., and Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive

capacity and interorganisational learning. Strategic

Management Journal, 19(5), 461-77.

Lane, P. J., Koka, B. R., and Pathak, S. (2006). The

reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review

and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of

Management Review, 31(4), 833-863.

Lane, P. J., Salk, J. E. and Lyles, M. A. (2001). Absorptive

capacity, learning, and performance in international

joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22(12),

1139-1161.

Laursen, K., and Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation:

The role of openness in explaining innovation

performance among U.K. manufacturing firms.

Strategic Management Journal, 27, 131-150.

Lettl, C., Hienerth, C., and Gemuenden, H. G. (2008).

Exploring how lead users develop radical innovations;

Opportunity recognition and exploitation in the field

of medical equipment technology. IEEE Transaction

on Engineering Management, 55,

219–233.

Lubinski, D. (2000). Scientific and social significance of

assessing individual differences: Sinking shafts at a

few critical points. Annual Review of Psychology,

51(1), 405–444.

Individual and Contextual Antecedents of Knowledge Acquisition Capability in Joint ICT Project Teams in Malaysia

77

Lyles, M.A. and Salk, J.E. (1996). Knowledge acquisition

from foreign parents in international joint ventures: an

empirical examination in the Hungarian context.

Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5), 877-

903.

Malairaja, C. and Zawdie, G. (2004). The ‘black box’

syndrome in technology transfer and the challenge of

innovation in developing countries. International

Journal of Technology Management and Sustainable

Development, 3(3), 233-251.

Minbaeva, D., Pedersen, T., Björkman, I., Fey, C. and

Park, H. J. (2003). MNC knowledge transfer,

subsidiary absorptive capacity, and HRM. Journal of

International Business Studies, 34(6), 586-599.

Nelson, R. R., and Winter, S. G. (1977). In search of

useful theory of innovation. Research Policy, 6(1), 36-

76.

Nemanich, L. A., Keller, R. T., Vera, D. and Chin, W. W.

(2010). Absorptive capacity in RandD project teams:

A conceptualization and empirical test. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 57(4),

674-688.

Ojo, A. O. and Raman, M. (2015). Micro perceptive on

absorptive capacity in joint ICT project teams in MSC

Malaysia status companies. Library Review, 64(1/2),

162 – 178.

Ojo, A. O., Raman, M., Chong, S. C., and Chong, C. W.

(2014). Individual antecedents of ACAP and

implications of social context in joint engineering

project teams: A conceptual model. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 18(1), 173-197.

Podsakoff, P. M., and Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in

organisational research: Problems and prospects.

Journal of Management, 12(4), 531-544.

Raman, M., Ojo, A. O., and Chong, C. W. (2014),

“Absorptive Capacity in joint project teams: Evidence

from Nigerian upstream oil industry”, Proceedings of

the 6th International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing, Rome; Italy;

21-24 October 2014, pp.140-145.

Ramasamy, B., Chakrabarty, A. and Cheah, M. (2004).

Malaysia’s leap into the future: an evaluation of the

multimedia super corridor. Technovation, 24, 871-883.

Richardson, C., Yamin, M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2012).

Policy-driven clusters, interfirm interactions and firm

internationalization: Some insights from Malaysia’s

multimedia super corridor. International Business

Review, 21, 794-805.

Schmitt, N., Cortina, J. M., Ingerick, M. J., and

Wiechmann, D. (2003). Personnel selection and

employee performance. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen,

and R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology

(pp. 77–105). London: Wiley.

Seeley, M., and Targett, D. (1999). Patterns of senior

executives’ personal use of computers. Information

and Management 35(6), 315–330.

Silva, N. D. and Davis, A. R. (2011). Absorptive capacity

at the individual level: Linking creativity to innovation

in academia. The Review of Higher Education, 34(3),

355-379.

Simosi, M. (2012), “Disentangling organizational support

construct: The role of different sources of support to

newcomers’ training transfer and organizational

commitment”,

Personnel Review, 41(3), 301-320.

Steensma, K. and Lyles, M.A. (2000), “Explaining IJV

survival in a transitional economy through social

exchange and knowledge-based perspectives”,

Strategic Management Journal, (21)8, 831–852.

Teece, D.J. (2012). Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus

entrepreneurial action. Journal of Management

Studies, 49(8), 1395 - 1401.

Todorova, G. and Durisin, B. (2007). Absorptive capacity:

valuing a reconceptualization. Academy of

Management Review, 32(3), 774–786.

Tripsas, M., and Gavetti, G. (2000). Capabilities,

cognition, and inertia: Evidence from digital imaging.

Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1147–1161.

Uzzi, B. and Lancaster, R. (2003), “Relational

embeddedness and learning: the case of bank loan

managers and their clients”, Management Science,

49(4), 383–399.

Van den Bosch, F. A. J., Van Wijk, R., and Volberda. H.

W. (2003). Absorptive capacity: Antecedents, models

and outcomes. In M. Easterby–Smith and M.A. Lyles

(Eds.), The Blackwell Handbook of Organisational

Learning and Knowledge Management (pp.278-301),

Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Van Riel, A. C. R. and Lievens, A. (2004). New service

development in high tech sectors: A decision making

perspective. International Journal of Service Industry

Management, 15(1), 72–101.

VandeWalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of a

work domain goal orientation instrument. Educational

and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 995-1015.

Volberda, H. W., Foss, N. J., and Lyles, M. A. (2010).

Absorbing the concept of absorptive capacity: How to

realize its potential in the organisation field.

Organisation Science, 21(4), 931-951.

von Krogh, G., Ross, J. and Slocum, K. (1994). An easy

on corporate epistemology. Strategic Management

Journal, 15(Special Issue): 53-71.

Zahra, S. A., and George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity:

A review, reconceptualization, and extension.

Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185-203.

Zhao, Z. J., and Anand, J. (2009). A multilevel perspective

on knowledge transfer: Evidence from the Chinese

automotive industry. Strategic Management Journal,

30, 959-983.

Yeh, Q. J. (2008). Exploring career stages of midcareer

and older engineers: When managerial transition

matters. IEEE Transaction on Engineering

Management, 55(1), 82–93.

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

78