A Comparative Study on User Characteristics of an E-car Pooling

Service in Universities in Europe

Fivos Galatoulas, Sesil Koutra, Pawel Rycerski,

Luis M. Ibarra Candanedo and Christos S. Ioakimidis

(*)

ERA Chair (*Holder) 'Net-Zero Energy Efficiency on City Districts, NZED' Unit, Research Institute for Energy,

University of Mons, 56 Rue de l’Epargne, Mons, Belgium

Keywords: Case-study, E-carpooling, MaaS (Mobility as a Service), Survey, University.

Abstract: An impactful solution for confronting critical environmental problems may be pursued within the context of

e-carpooling services. Nevertheless, a crucial part in our intervention through the introduction of efficient

carpooling systems is that of the conceptualization of user preferences and attributes. This study presents a

comparison between two surveys focused on a respondent sample consisting mainly of members of a

university community. Specifically, the first survey involved students and employees of a private academic

institution (University of Deusto, Bilbao, Spain) while the second members of a public institution in

(University of Mons, Hainaut, Belgium).

1 INTRODUCTION

The mobility concept of e-carpooling offers not only

an alternative means of covering the increasing

requirements for human mobility, but also a low-cost

measure to alleviate the effects for a number of

problems, including traffic congestion, energy

consumption and environmental degradation, among

others

(Bruglieri et al., 2011) . Generally, carpooling

aims at increasing the vehicle occupancy, focusing on

the transportation of a group of individuals from a

given origin to a specific destination at the same time

(Katzev, 2003). In particular, it refers to the

establishment of agreements between a driver and one

or more passengers to share a ride in a single vehicle,

rather than making the same trip individually

(Dimitrakopoulos et al., 2012). The driver and the

passenger(s), also referred to as “car poolers”, agree

in advance to share the fuel and other relevant costs

(e.g. toll fees) for a specific trip in order to have a

mutual benefit on the transportation costs. Even

though the term car sharing is sometimes used

(mainly in the United Kingdom and to some extent in

Australia and New Zealand) as a substitute for or

interchangeably with what is known as carpooling in

the academic and increasingly popular discourse

(Kent and Dowling, 2013, Stillwater et al., 2009), a

main difference in carpooling is that the individuals

share a common route, not only the car (Katzev,

2003). In the most typical form of carpooling, both

driver and car poolers have the same origin and

destination, while more complex structures occur if

they share only a part of a given trip (Vanoutrive et

al., 2012). The innovative characteristic of e-

carpooling is the combination of carpooling with the

emerging electric vehicle technology.

In addition, transportation is considered as one of

the primary fuel use sectors worldwide, while being

responsible for a significant share of greenhouse gas

(GHG) emissions. Given the imminent depletion of

oil reserves and the resulting volatility of fuel prices

in international markets, the widespread adoption of

electric vehicles is often viewed as a feasible

alternative to vehicles with internal combustion

engines that could contribute, to a significant extent,

to the decarbonisation of the transportation sector

(Chan and Shaheen, 2012).

From the authors’ point of view, the combined use

of car sharing and carpooling services with electric

vehicles can multiply the potential benefits in terms

of reduction on the traffic congestion, air and noise

pollution, as well as dependence on fossil fuels. To

this end, this paper presents the results of two surveys,

the first conducted at the University of Deusto (UD),

Bilbao, Spain and the second at the University of

Mons (UMONS), Belgium in an attempt to identify

differences and similarities between the academic

communities on their perception on the transition to

200

Galatoulas, F., Koutra, S., Rycerski, P., Candanedo, L. and Ioakeimidis, C.

A Comparative Study on User Characteristics of an E-car Pooling Service in Universities in Europe.

DOI: 10.5220/0006302202000207

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2017), pages 200-207

ISBN: 978-989-758-241-7

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

electromobility and alternative modes of transport.

The purpose of this work is twofold, first to record the

everyday practices and preferences of the employees

and students regarding the use of public transport in

different cities-countries, to explore their attitude

towards the use of electric vehicles, including cars,

scooters and bicycles, and the adoption of e-car

sharing/carpooling as a means of transport and finally

to examine the reasons behind the groups choice of

mode of travel depending on the local transportation

framework, national commuting statistics and

possible implicate attributes.

2 METHOD

2.1 Survey Characteristics

A survey questionnaire was prepared and distributed

to members of the university campus at both

occasions via a Google platform. Each participant

was selected randomly but asked to validate his

academic identity. Respondents were explained

broadly the concept of carpooling and were invited to

carefully read questions before answering.

2.2 Description of Samples

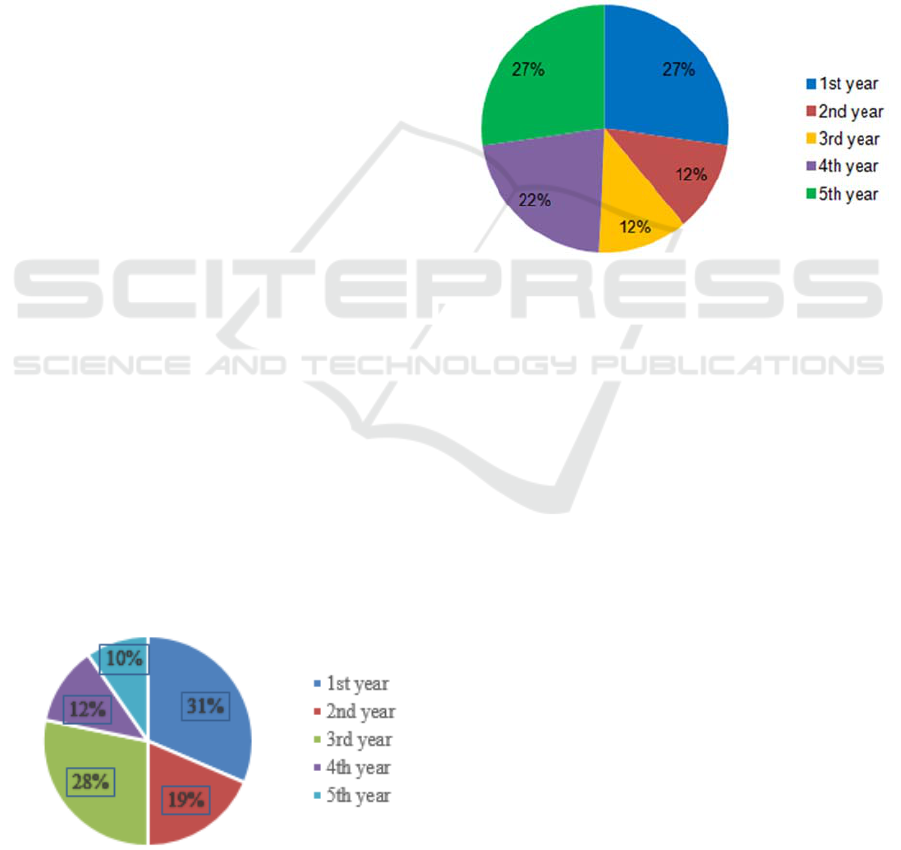

Our sample in the first case, the survey conducted in

2014 at the UD, consisted of a representative sample

of 124 students of which 49,2% were women. The

purpose of this survey was to collect information on

the use of public transport and analyze the attitude of

the respondents towards new modes of transport and

use of electric vehicles, including cars, scooters and

bicycles. The questionnaire included an age indicator

in order to divide the respondents into groups by year

of tuition. The majority of the respondents belongs to

the age group 17-18 years old (1st year), followed by

3rd year students and respondents from the final years

having the lowest percentage, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Percentage breakdown by age group of the UD

sample.

The second under study survey (26 questions) was

conducted at the UMONS campus during the period

from 17/6 to 30/7/2015 in a sample of 59 students.

The purpose of the survey was to gather data on the

user preferences and analyse the attitude of the

respondents regarding the concepts of carpooling and

electro-mobility, in order to identify their

characteristics as potential users of a university-based

e-carpooling system in the city of Mons. The survey

was based on a random sample of 59 Bachelor (51%)

and Master (49%) students. More specifically, the

sample consists mainly of students in their 1st (27%),

4th (22%) and 5th (27%) year of studies, as shown in

Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Survey characteristics.

3 RESULTS

In this section, the key results of each survey study

are presented in order to provide the necessary

information for evaluating the extent to which the two

population samples differ in terms of response data.

3.1 Student Survey Study at the

University of Deusto

The UD is located in Northern Spain in the heart of

the economic and cultural capitals of the Basque

Country - Bilbao and San Sebastian. UD was founded

in 1886 due to the Basque community’s desire for

independent education and the Society of Jesus's wish

to move its School of Higher Studies in Laguardia to

a more central place. The university has more than

10.000 students and approximately 600 members of

staff (Morigi and Trombetti, 2006).

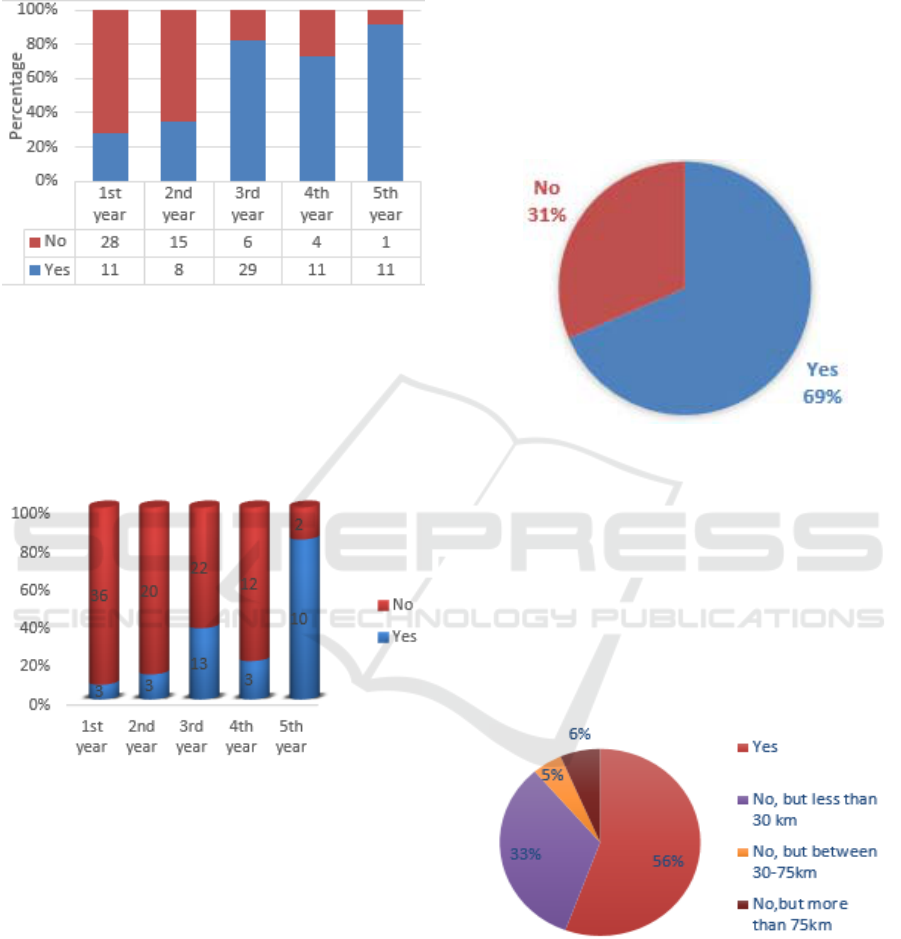

3.1.1 Part I: Driving Profile

The first query of the survey aimed to determine the

percentage of the respondents that hold a driving

license, with percentages of possession increasing

A Comparative Study on User Characteristics of an E-car Pooling Service in Universities in Europe

201

accordingly to year of tuition. Fig. 3 presents the

percentage share of driving license holders per age

group.

Figure 3: Percentage share of respondents holding a driving

license.

The next query referred to private vehicle ownership.

Of the respondents holding a driving license, a

percentage of 45,7% owns a car. Accordingly, Fig. 4

illustrates the percentage of survey respondents that

own a car in each age group.

Figure 4: Percentage of total respondents owning a car.

3.1.2 Part II: Use of Public Transportation

Nearly a percentage of 80% of the respondents use

public transport in Bilbao, most of which belong to

freshman years, while more experienced students are

ranked lower in terms of public transport use. The

overwhelming majority of the respondents (95%)

reported the use of the subway, because of the

geographical coverage, with bus transport being also

a widely used means of transport (65% of the

respondents), given the good connections between

buses and the fact that there are some areas not served

by the Metro service. Most of the younger

respondents (1

st

-2

nd

year) use it on a daily basis, while

the rest use it at most twice a week

3.1.3 Part III: Use of New Technologies

Regarding the possession and use of new

technologies in the form of a smart phone with

internet access, a percentage of 70% of the

respondents answered affirmatively (Fig. 5), with

people in earlier years of their tuition stating that it is

one of the primary means of communication, while

the other groups mentioned having the basic skills to

send emails and/or open files.

Figure 5: Percentage of Smartphone users.

3.1.4 Part IV: Residential Distribution

In terms of sociodemographic and transportation

accessibility, the results of the survey also show that

only 5% of the people interviewed reside between 30

and 75 km from Bilbao, while a percentage of 33%

resides outside the city center but within a distance of

30 km. Fig. 6 presents the distribution of respondents

following the query of the distance of their residence

from the center of the city of Bilbao.

Figure 6: Distance of residence from the city centre.

3.1.5 Part V: Attitude towards

Electromobility/ Carpooling

A key finding of this survey was that most of the

respondents opt for an electric vehicle to move

around Bilbao or within 30 km, while the order of

preference is electric car, electric scooter and electric

SMARTGREENS 2017 - 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

202

bicycle with percentages of 53%, 37% and 10%

respectively. Moreover, a percentage of 60% of our

sample considers electric vehicles as an economic and

environmental option, while the rest 40% stated that

it is not only economic and environmental, but also

offers quick access. Regarding the perception of the

electric vehicle concept from the respondents,

approximately 85% of them believe that an electric

car has a single electric motor, while the remaining

15% reported that electric cars have both an electric

motor and a gasoline engine.

In addition, the survey included a set of queries to

identify the attitude towards electromobility and the

willingness to use non-traditional modes of transport.

Remarkably, only 35% of the people interviewed are

not willing to rent an electric means of transport,

while of the remaining 65%, a share of 75% would

rent an electric car and the rest 25% would rent an

electric scooter. A percentage of 85% of the

participants in the survey reported that they would

share a car to go to work or to the same destination

with the same schedule. Equally important, a share of

73% of the respondents stated that, for electric

transport services, they would pay the same amount

with the daily cost of public transport, while the rest

27% is willing to pay 10% more.

In the last part of the survey, the participants were

asked to express their opinion about the electric

means of transport, specifically for the electric car. In

general, the respondents believe that it is an expensive

option, because of the cost of charging, and that there

is a lack of the required infrastructure, as there are

only a few charging points in the city. Furthermore,

the survey participants note that electromobility will

eventually be the most viable way for transportation

purposes, a fact that should be also taken into account

in the public sector. Regarding their opinion for

MaaS, thus, car sharing and carpooling as alternative

modes of transport, the participants consider this as

an opportunity to save costs, prevent traffic

congestions, meet new people, and in general they

would share a car to go to their work with their

colleagues or people that wish to move to the same

place with the same schedule.

3.2 Student Survey Study at the

University of Mons

This section presents the results of the survey

conducted at UMONS, which is a French-speaking

public university in the Hainaut province of Belgium,

near the French-Belgian border and it is situated

approximately 50 km from Brussels. UMONS was

created in 2009 following the merger between the

University of Mons-Hainaut and the Faculty of

Engineering of Mons. Today, the university has more

than 6.000 students and more than 1.000 employees

(Ioakimidis et al, 2016).

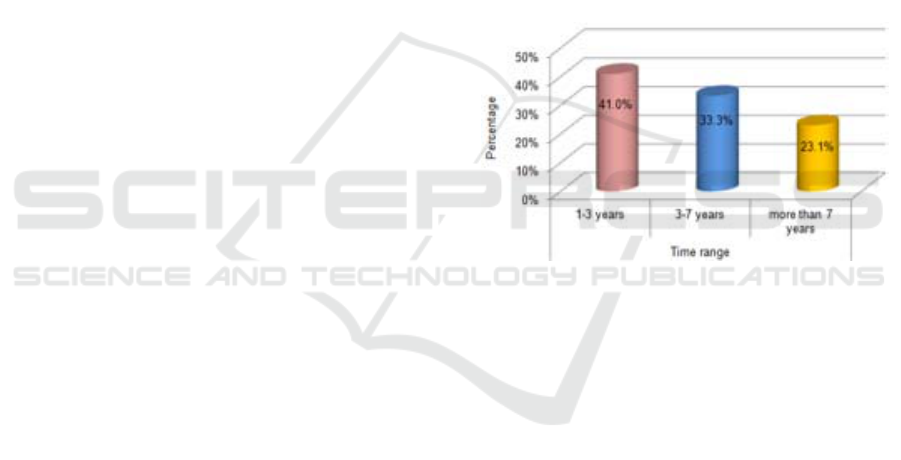

3.2.1 Part I: Driving Profile

Framing their profile, the first query aimed to

determine the respondents that hold a driving license

and it was answered affirmatively by the majority of

them (66.1%). With respect to the number of years

holding a license as an indicator of the driving

experience, more than 40% of the relevant

respondents have held their license for 1-3 years,

more than 30% of them have possessed their license

for a longer period of 3-7 years, while significant is

also the percentage of respondents with a driving

license for more than 7 years (23.1%), as shown in

Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Time distribution of driving licence possession.

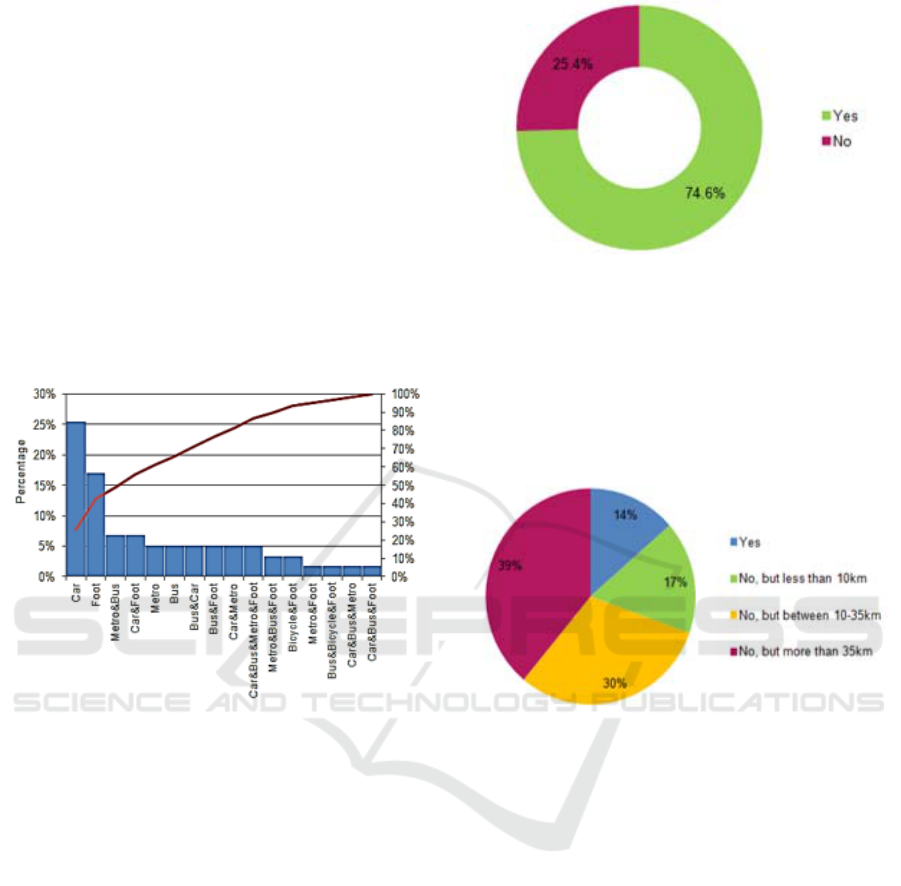

3.2.2 Part II: Use of Public Transportation

A high share of the interviewed persons uses only the

car for daily commuting to the university (25%),

while interesting is also the number of users that

prefer going on foot to their destination (17%).

However, a significant part of the respondents

combines public transportation (car-metro, bus-car,

bus-foot, etc.) to cover the daily transport needs. Fig.

8 presents graphically the results discussed. In

general, the overwhelming majority of survey

participants makes use of public transportation (not

necessarily for commuting to the university only) on

a daily basis (86%), while only 7% of them once per

week. Obviously, the good connections between the

various means of transportation encourage the

frequent use by commuters; however, the percentage

of car use for commuting to the university still

remains high (25%).

Two important issues regarding the use of public

transportation are: (i) the estimated time from their

home to the university, and (ii) the monthly expenses.

A Comparative Study on User Characteristics of an E-car Pooling Service in Universities in Europe

203

With respect to the estimated trip time, more than

30% of the interviewees need between 15-30 min for

a single trip, while approximately 30% of them

estimate 30-60 min per trip. Less than 5% of them

need only 5 min (residence in Mons) and more than

10% take more than 60 min to arrive at the university

(due to inadequate geographical coverage of public

transportation, long distances, bad connections, etc.).

The second key factor and incentive for the

encouragement of public transportation use is the

indicator of monthly expenses. The majority of the

respondents (more than 40%) spend less than 25€ per

month for daily commuting to the university

(obviously using public transportation), while a

significant percentage of 17.4% of them spend more

than 65€ monthly (possible car use).

Figure 8: Use of means of transportation for commuting to

the University.

3.2.3 Part III: Use of New Technologies

Regarding the possession and use of new

technologies in the form of a smart phone with

Internet access, a percentage of approximately 75%

of the respondents answered affirmatively (Fig. 9),

while more than 95% of them possess a personal

computer with Internet access, considering them as

primary means of communication.

Figure 9: Possession of smart phone with Internet access.

3.2.4 Part IV: Residential Distribution

The results show that only 14% of the respondents

reside in the city, while the rest of them prefer

commuting as they reside in a distance between 10-

35 km (30%) or in a distance of more than 35 km

(approximately 40%) from the city centre (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: Residence in the city of Mons and distance from

city centre.

3.2.5 Part V: Attitude towards

Electromobility/ Carpooling

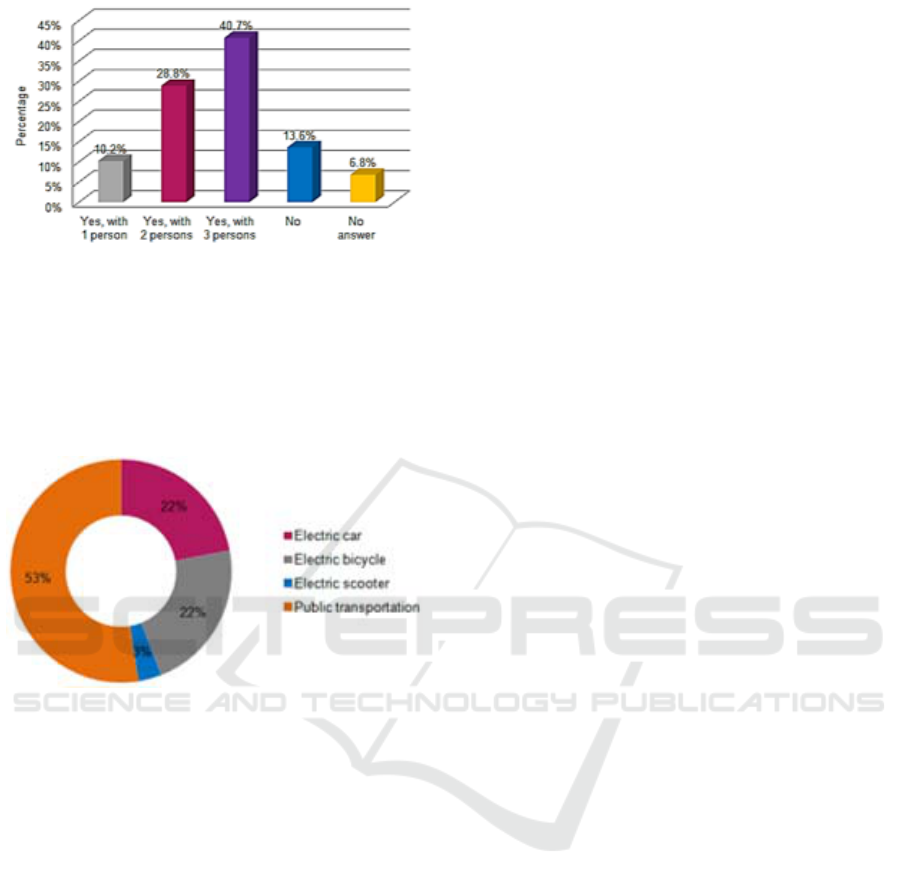

In addition, the survey included a set of queries to

identify the willingness to use non-traditional

mobility concepts. It is interesting to note that a

remarkably high percentage of the respondents

answer affirmatively to the idea of carpooling with

one or more persons (almost 80%), while only 13.6%

of them show no interest in this mobility concept, as

depicted in Figure 11.

Following the willingness for carpooling, the

respondents were asked for their potential

participation in carpooling if financial or ecological

criteria are promoted. Approximately 60% of the

interviewees would opt for carpooling for financial

reasons, while more than 50% of them are encouraged

by ecological initiatives. It is interesting to note that

more than 40% of them support the concept of

carpooling even if they are not the drivers.

SMARTGREENS 2017 - 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

204

Figure 11: Willingness to carpool.

Another finding of the survey is that more than a half

of the respondents (53%) opt for public transportation

to move around Mons or within 30 km compared to

EVs, while the preference for the latter is electric car

(22%), electric bicycle (22%) and electric scooter

(only 3%), as shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Preferable means of transportation in the city of

Mons.

The main reasons for the users’ preferences on the

means of transportation for the trips in the city of

Mons are a combination of ecological, financial and

time criteria (roughly 30%), while the combination of

ecological and financial criteria is also crucial for the

interviewees (approximately 24%). Moreover, the

estimated time for quick access per se is also

considered as important factor for the users’ choice.

In the last part of the survey, the participants were

asked to express their opinion about the electric

means of transportation and their willingness to use

them for daily commuting. Despite the fact that 1 out

of 2 participants shows no interest in renting an EV

for commuting to the university, an additional key

finding regarding this part of the survey is that

approximately 30% of them would prefer to rent an

electric bicycle and roughly 20% would prefer an

electric car.At a first glance, this finding indicates that

the users are cautious about electro-mobility,

considering EVs as an expensive or not an

appropriate option for their daily commuting to the

university. A main reason for this perception can be

attributed to the complex infrastructure required to

support electro-mobility. On the other hand, almost

30% of the survey participants would share their

rented EV in order to commute to the university,

while 25% of them show no willingness for such a

concept (the rest survey participants gave no answer).

The last predictors examined the users’ willingness to

be charged with extra fees for renting an EV

compared to a conventional one. Specifically, a share

of 54% of interviewees would not pay more to benefit

from the use of an EV, while 19% of them could

afford additional fees of more than 10% (only 3%

report more than 25% for the possession and use of

an EV).

4 DISCUSSION

Despite the numerous environmental benefits

deriving from the adoption of e-carpooling as a mode

of transportation (reduction of air pollution, fuel

consumption savings, cost-effectiveness and higher

vehicular occupancy leading to a subsequent decrease

of cars on highways), it has not yet sufficiently

outspread in European cities. In our study, an attempt

to identify the differences in motivation and

preferences of students, belonging to two different

University settings, concerning urban solutions on

transportation was performed through the assessment

of factual data and survey responses.

Both student population samples were similar in

transportation accessibility, age distribution and

agglomeration size. However, students in Bilbao

reside closer to the center of the city than their fellow

students in Mons.

Importantly, an impactful fact is Belgium’s high

rate of daily commuters, claiming first place in the

EU. On average, Belgians commute 53.2 minutes a

day, compared to the European average of just less

than 45 minutes. One in five Belgians spend two

hours a day commuting. The time Belgians spend

commuting scores to an average of nearly seven full

days a year (Eurostat, 2016). On average, Europeans

spend 45 minutes a day on public transport with the

Spanish dedicating 51.6 minutes per day to

commuting. From an unexperienced point of view

these numbers would assimilate the mobility

perspective of both regions, nonetheless one must

take account of the average commuting distance per

country, with Belgians topping cross-border rate of

commuting in 2015 where more than one in five

(21.9 %) persons commuted to work in a different

region. This fact can explain the difference observed

A Comparative Study on User Characteristics of an E-car Pooling Service in Universities in Europe

205

in the query regarding preferable means of transport

in the city, with public transportation gathering higher

percentages in the UMONS student sample, while on

the contrary students of the Basque institution

selected the EV car as their optimal mean.

In addition, this can be explained to a great extent

if viewed in the context of the economic incentives

for the promotion of electric vehicles provided by the

Governments of Spain and the Basque Country, given

that they can be combined cumulatively in order to

increase the total amount of subsidy. Recently, the

Spanish Government approved the new program for

subsidizing the purchase of battery electric vehicles

with at least 4 wheels, depending on the range and the

type of vehicle (Spanish Ministry of Industry, 2013).

In the Basque Country in particular, the local

Government provides subsidies for the purchase of a

wider range of vehicles, including a maximum

amount of 5000 € for a plug-in hybrid or a pure

electric vehicle, as well as for an electric vehicle with

range extender, 750 € for an electric motorbike and

400 € for an electric moped. Moreover, a gradually

increasing per vehicle subsidy applies to the case of

multiple vehicles (of the same category) purchase.

Regarding the charging infrastructure, there is a

subsidy of up to 40% of the cost of the complete

installation (excluding IVA). For residential parking

lots or fleets of electric vehicles, the maximum

amount cannot exceed 500 € per charging point, while

for public-use charging points the maximum

economic assistance depends on the type of the

installation, with a maximum amount of 2000 € for

mode 3 charging and 5000 € for mode 4 (fast DC)

charging (EVE, 2013).

In contrast, the results retrieved from the survey

in UMONS, imply that electro-mobility has not

spread to the full extent of its potential, but still from

the user’s perspective there are two major barriers in

owning and/or using an electric car: (i) it costs more

than a car with an internal combustion engine, and (ii)

it has in general a limited range compared to a

conventional vehicle It is important to note that the

total amount of the economic aid cannot exceed the

20% of the total eligible cost of the vehicle.

Similar acceptance rates were recorded in

identifying the key factors that could assist in

predicting the willingness to carpool. Specifically, the

findings of the UMONS survey indicate that 4 out of

5 survey respondents would participate in carpools

(80% for the first sample), while almost 3 out of 10

participants would rent and share (carpool) an EV in

order to commute to the university, conflicting with

the high EV acceptance rates scored in the Basque

study. The reasons for carpooling in both targeted

samples recognized as incentives, financial gains,

environmental awareness and time-saving. The

findings of the first survey also include that 2 out of 3

respondents are willing to rent an electric means of

transport, while a percentage of 85% of the

respondents would share a car to go to work or to the

same destination with the same schedule.

Furthermore, this preliminary approach reveals that 1

out of 4 respondents is willing to pay a premium of

10% of the daily transportation cost with public

means in order to use electric transport services in

Bilbao.

The final aim of this study was to evaluate the

level of acceptance and attitude towards the transition

to electromobility. Initially, this work considers the

geographical distribution of residence for the

population under study, given that almost 9 out of 10

individuals reside close to the city of Bilbao. This

implies that a significant part of the sample

potentially combines different modes of transport in

order to commute to and from the university. The

results of the survey show that at least 4 out of 5

respondents use public means of transport to cover

their transportation needs.

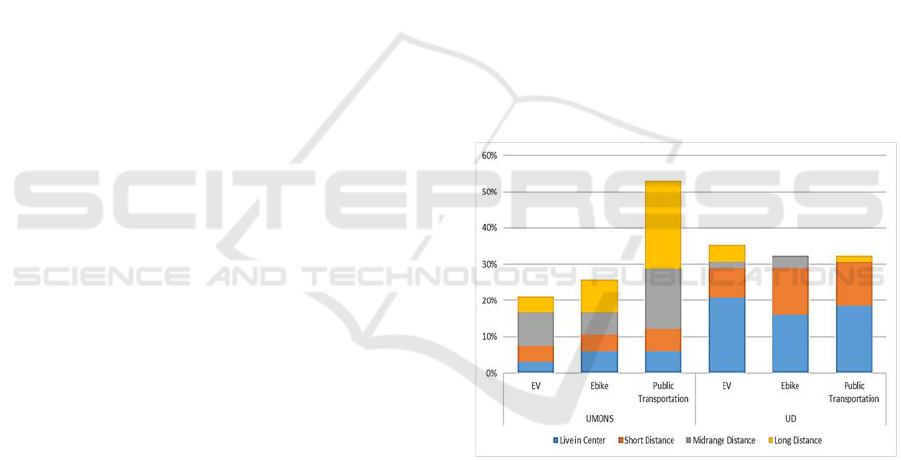

Figure 13: Comparative representation of preferable mode

of transport per study group linked to distance from city

centre.

Remarkably, most of the respondents from the

UMONS study use a private vehicle (25%) with

second preferred way of transfer being by foot, a fact

connected to the short range distances a student must

cover for inter-campus transport within the scale of

Mons. The electric car is considered as the most

popular choice, with electric scooters and bicycles

being secondary options for students of UD when at

the same time students in UMONS tend to be cautious

with the concept of electromobility, as depicted in

Fig.13.

SMARTGREENS 2017 - 6th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

206

5 CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this work indicate that both survey

respondents are in support of public transportation,

while the users’ acceptance on renting an electric car

in order to commute to the university is relatively low

yet encouraging in the case of UMONS. Therefore, a

university-based MaaS e-carpooling concept can be a

promising solution as the total costs of owning and/or

using an EV spread among many users and it becomes

part of the public transportation system for

complementing both local and long-distance trips.

To conclude, the results obtained within the frame

of this work reveal that the members of the first case

study show a positive attitude towards using both car

sharing/carpooling services and electric vehicles.

Future work includes a comprehensive study for

examining the case of implementing a car

sharing/carpooling service with electric vehicles

within universities, addressing these issues by

enlarging the sample base and recording preferences

with objective measures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the EC under the FP7

RE-SIZED 621408 (Research Excellence for

Solutions and Implementation of Net-Zero Energy

City Districts) project.

REFERENCES

Bruglieri M., Ciccarelli D., Colornia A. and Luè A., 2011.

PoliUniPool: A carpooling system for universities,

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sci., vol. 20, pp. 558–

567.

Chan N. D. and Shaheen S. A., 2012 Ridesharing in North

America: Past, Present, and Future, Transport Reviews,

vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 93–112.

Dimitrakopoulos G., Demestichas P. and Koutra V., 2012.

Intelligent management functionality for improving

transportation efficiency by means of the carpooling

concept, IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 13, no.

2, pp. 424–436.

Ente Vasco de la Energía (EVE) / Departamento Desarrollo

Económico y Competitividad / Gobierno Vasco, 2013.

Programa de ayudas en transporte y movilidad

eficiente, Condiciones Generales (Año 2013).

Available:

http://www.eve.es/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=ad7

80aa5-abdb-4bbd-bafd-00e5a0b60da3.

Eurostat, 2016. Europe in Figures: Eurostat Yearbook 2016.

Publications Office of the European Union.

Ioakimidis C. S., Koutra S., Rycerski P. and Genikomsakis

K. N., 2016. User characteristics of an electric bike

sharing system at UMONS as part of a smart district

concept, in Proc. 2016 IEEE Int. Energy Conf.

(ENERGYCON), Leuven, Belgium.

Katzev R., 2003. Car Sharing: A New Approach to Urban

Transportation Problems, Anal. of Social Issues and

Public Policy, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 65–86.

Kent J. L. and Dowling R., 2013.Puncturing automobility?

Car sharing practices, J. of Transport Geography, vol.

32, pp. 86–92.

Ministerio de Industria, 2013. BOE-A-2013-4461, Boletín

Oficial Del Estado. Núm. 101. Sábado 27 de abril de

2013. Sec. I. Pág. 32072. I.

Morigi, L. and Trombetti F., 2006. Quality assurance in

higher education. A case study: the Deusto University

in Bilbao. Assessing Quality in European Higher

Education Institutions. Physica-Verlag HD, 133-146.

Stillwater T., Mokhtarian P. L. and Shaheen S. A., 2009.

Car sharing and the built environment: Geographic

information system based study of one U.S. operator,

Transportation Research Record, vol. 2110, pp. 27–34.

Vanoutrive T., Van De Vijver E., Van Malderen L.,

Jourquin B., Thomas I., Verhetsel A. and Witlox F.,

2012. What determines carpooling to workplaces in

Belgium: Location, organisation, or promotion? , J. of

Transport Geography, vol. 22, pp. 77–86.

A Comparative Study on User Characteristics of an E-car Pooling Service in Universities in Europe

207