Searching of Sundanese Archaic Words in Inner and Outer Badui

Davin Rusady and Sri Munawarah

Faculty of Humanities, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

{davin.rusady, sri.munawarah }@ui.ac.id

Keywords: Archaic, Sundanese, Inner Badui, Outer Badui.

Abstract: Badui people came from the old Sundanese Kingdom which is the Pajajaran Kingdom who was hiding

when the kingdom started to collapse at the early of the 17

th

century following the rise of Islamic teachings

by the Banten Kingdom. The Badui was the people of the Pajajaran Kingdom who fled to Lebak district and

settled there. After settling down, they still apply the traditional life customs that being inherited from

generation to generation. Therefore, there is a possibility the Badui people inherited some Sundanese

archaic words. This study attempts to answer whether there are any Sundanese archaic words in the Inner

and Outer Badui areas. The goal of this research is to inventory Sundanese archaic words in the Inner and

Outer Badui areas. The data were collected by interviewing informants in 14 villages with listening,

observing, and writing informants’ utterance. The methods used in this research are checking the words and

compare it to the dictionary of Sundanese archaic words. The results show that there are 633 words used by

the Badui people and as many as 47 words (7,42%) of it are Sundanese archaic words that are not used

anymore in Bandung, but still used in Badui area. Moreover, the archaic vocabularies are not only found in

Inner Badui area, which is considered more exclusive due to the strict application of customary rules but

also found in Outer Badui area that is considered to be contaminated by the outermost areas because the

application of customary rules is laxer.

1 INTRODUCTION

Each language certainly has a variety of dialects

because dialect is part of a language (Wardhaugh

2006). One of the interesting phenomena to be

traced can be found in Badui area because Badui

people are speaking in the ancient Sundanese

language. According to Lauder (2006), the closed

society situation allows the Badui society to preserve

the ancient Sundanese vocabulary. It encourages

researchers to conduct research on vocabulary words

archaic Sundanese in Inner and Outer Badui.

Fromkin et al. (2003) have proposed that a word

can be described as archaic because there is no

speaker who uses the vocabulary and its existence

was already replaced. For example, mokla 'blood' in

Sundanese is rarely used in Bandung and

surrounding areas. The word is replaced with getih

which also means 'blood'. Meanwhile, the word

mokla still exist in the Badui area because Badui

society still speaks in ancient Sundanese.

Badui society is a group of people who still

maintain the original culture. They inherit the

customary rules of pikukuh from generation to

generation. Geographically, Badui society is divided

into two groups, namely Inner Badui and Outer

Badui. Inner Badui area includes Cikertawana,

Cibeo, and Cikeusik Village. Meanwhile, a recent

report on the amount of Outer Badui area (Baduy

Kembali 2016) said that the Outer Badui area covers

61 other villages.

At first, the Badui speak in Sundanese. Their

language belongs to the Sundanese-Banten dialect

category, the Badui subdialects. Unlike the Banten

dialect, the language used in Badui is not influenced

by the Javanese language. In addition, the language

used in Badui has a special vocabulary for counting

good days. Therefore, customs, religions, ancestor

stories, and so forth are kept in their speech

(Permana, 2006).

One of the earliest writings about the Bedouin

community comes from reports C.L. Blume, during

the botanical expedition to the area in 1822.

According to Blume, the Badui community

originated from the old Sundanese Kingdom, which

is the Pajajaran Kingdom, who hid while the

kingdom collapsed in the early 17

th

century

592

Rusady, D. and Munawarah, S.

Searching of Sundanese Archaic Words in Inner and Outer Badui.

DOI: 10.5220/0007171505920596

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 592-596

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

following the Islamic teachings of Banten Kingdom

(Permana, 2006).

In connection with those statements, researchers

concluded that the Badui people were the people of

the Pajajaran Kingdom who fled to the Lebak

district and settled there. Once settled, they still

apply rigorous royal life procedures as the

inheritance. It is also possible that the Badui society

has inherited archaic vocabularies in ancient

Sundanese. Therefore, the problems in this paper are

what kind of Sundanese archaic vocabularies that

still remain in the Badui area. The purpose of this

research is to find Sundanese archaic vocabulary and

vocabulary that replacing the Sundanese archaic

vocabulary in the Badui area.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

This research is the first study of Sundanese archaic

vocabulary. Therefore, researchers did not find

previous research that discusses the searching of

archaic vocabulary in Sundanese. Even so,

researchers found several studies that discuss the

searching of archaic vocabulary in other regional

languages, such as Minangkabau and Mandailing

languages. In the Pariaman dialect of Minangkabau

language, Yulis et al. (2013) stated that there are

archaic vocabularies that are no longer used in the

Koto Tabang region. The study also reveals that

there are five factors that can cause these

vocabularies to be archaic, among others the

growing number of younger generations, the

declining number of older generations, the

unfavourable attitudes towards local languages, no

language interaction, and the influx of Indonesian

vocabulary entry into in the local language. In

addition, in the Mandailing language, Lubis (2013)

stated that there are eighty archaic vocabularies.

Thirty vocabularies have never been used in daily

life. Some of the causes of these vocabularies are

archaic, among others modern cultures replacing

traditional cultures, replacements by synonyms, and

the influence of the introduction of Indonesian

vocabulary into local languages.

There are also several other studies that can

provide information to researchers in understanding

the condition of observation points, such as research

entitled Forest Land Acquisition in Badui Areas by

Badui Communities from 1953 to 1985 in 1999,

Environmental Wisdom in Baduy Society in 2006,

and Baduy Ecotourism: The Linkage between

Pikukuh, Environment, and Tourism in 2010. Those

three studies contain an overview of Badui area,

such as Banten history, the Badui origins,

geographical location, territory, social organization,

community structure, governance system, public

trust, kinship and marriage, livelihood, also

settlement distribution. Such information may assist

the researcher in collecting data and writing research

reports.

In the book entitled Potret Kehidupan

Masyarakat Baduy (Portrait of Baduy Society’s

Life) also disclosed about the origin of Badui tribe

society. There are several opinions on the origin of

Badui name. According to some folklore in Banten,

the Badui name came from the name of a river

named Cibaduy. However, the name was born after

the first self-isolated community opened the village.

There are other opinions that say the Badui comes

from the word Budha and turned into Baduy. There

is also a saying that the name comes from the word

Baduyut because in the village that is used as a place

to live a lot of Baduyut trees, a kind of banyan.

Meanwhile, surely the word Badui was born after

the alienated community built the village

(Djoewisno, 1987).

The alienated society was the Pajajaran people

who fled for fear of enemy pursuits, especially by

the Cirebon Kingdom. Eventually, they came to a

place protected by hills and mountains (Sodikin,

2006). Therefore, it is possible that the Badui people

who live today are the descendants of King

Siliwangi and his guards.

Badui society is divided along strictly socio-

political lines into two distinct subcultures. These

subcultures are distinct geographically. There is no

firm evidence that explains the separation of the

Badui into Inner and Outer (Sodikin, 2006).

However, in a dissertation entitled “Badujs En

Moslims in Lebak Parahiang Zuid Banten”, Geise

(in Sodikin 2006) says that the Inner and Outer

Badui are a single socio-cultural entity. Geise argues

that they are the same community because the Outer

Badui situates their houses overlooking one of the

villages in the Inner Badui area. This happens

because there is a sense of one's offspring or at least

feel that their ancestors have ever worshiped

together against one of Inner Badui villages. This

unity can be clearly seen in the organization of

sacred ceremonies, such as harvest ceremony, rice

planting ceremony, and Kawalu ceremony.

According to Geise (in Sodikin, 2006), the

emergence of the Inner and Outer distinction in

Badui society is a symptom found in various forms

in Indonesia of two-level hierarchies. Geise

describes Kajeroan, the Inner Badui, as a group that

upholds sacred values, acts in the manner of a

Searching of Sundanese Archaic Words in Inner and Outer Badui

593

respected person, or the nobility and leads, while

panamping, the Outer Badui, is a group that upholds

every day, laxer values, has the desire to worship,

and belongs to the masses.

According to Sodikin (2006), the Kajeroan or

Inner Badui are the group who arrived first in the

area they now occupy. This area is called Taneuh

Kajeroan and its inhabitants are called Urang

Kajeroan ‘insiders'. The Inner Badui inhabit three

villages or Tangtu Tilu: Cibeo, Cikeusik, and

Cikertawana. The other group, the Panamping, or

Outer Badui, are called Urang Kaluaran 'outsiders'.

The Outer Badui community groups live in other

villages outside the Inner Badui areas and their

village continues to expand from year to year.

3 METHODS

Research techniques that researchers will do are the

technique of interviewing with a direct listing

(Ayatrohaédi, 2002). The interview will be done by

asking a list of questions that researchers have

prepared. The questionnaire will be asked by the

informant by pointing to the object around the

informant (if any), explaining the form, usefulness,

and nature of the vocabulary in the questionnaire.

After asking a list of questions, the researcher will

directly write the spoken vocabulary using lexical

writing. Lexical writing will be performed to

determine how the pronunciation or the

pronunciation of the vocabulary of native speakers.

Lexical writing referring to The International

Phonetic Alphabet (Chambers and Trudgill, 2004)

because the researcher must use the lexical symbol

in writing so that readers know the pronunciation or

vocabulary proper pronunciation.

Interviews will be conducted in the Kanekes

Village, Leuwidamar District, Banten Province,

West Java. The village was selected as the main

area, so the observation point would be at the hamlet

level. The number of observation points should be

enough to provide a representative sample. They

should be as evenly distributed from each other as

possible throughout the study area. The goal is that

the set of all selected villages should appear as

evenly spread and the sample size should be no less

than 20% of a total number of villages. These

criteria are thought adequate to produce a

comprehensive picture of the language situation

(Lauder, 2007). In this study, researchers sampled a

total of 14 from 64 villages in the Badui tribe areas.

Observation points located in Inner Badui, among

others, Cibeo, Cikertawana, and Cikeusik village.

Meanwhile, observation points that are located in the

Outer Badui, among others Cijengkol, Cisadane,

Cieurih, Cipaler, Cikopeng, Cisaban, Balinbing,

Ciwaringin, Karakal, Kaduketug, and Kompol

villages.

The selection of informants for dialectology

research needs to follow a strict set of criteria. It is

advised that they are Non-mobile, Older, Rural, and

Male (NORM). The thinking behind this is to make

sure the informants can represent the language and

not influenced by other external languages or

cultures. Non-mobile means rarely traveling and free

from experiences other than those in the local

culture; Older means older people are more likely to

use archaic vocabulary; Rural means less likely to

be exposed to outsiders or foreigners; and Male

because traditionally men were thought to be better

represent the local language (Lauder, 2007).

The person who meets the NORM criteria needs

to be found at each observation point. The person

should be someone who speaks the language as a

first language. In order to make such decisions, the

researcher works with a research assistant who is a

native speaker of the local language and a bilingual

who can communicate well with the researcher and

the local community.

All 14 informants were interviewed for this

study, one for each observation point. All of the

informants were considered to be suitable as they

had used Sundanese as their first language. None of

the informants had any history of formal education.

This is due to one of the customary rules that

prohibits Badui people from going to school. Ideally,

the age of informants should be between 40 to 50

years old (Ayatrohaédi, 1979). However, a number

of informants who were older than 50 are chosen

due to the absence of informants that meet the

criteria in some villages. These informants were in

good physical, displayed no signs of senility, and

used the language fluently.

To obtain a good overview of the linguistic

phenomenon, a questionnaire that fit for the purpose

need to be developed. The questionnaire used in this

study is 200 Swadesh basic vocabularies (Lauder,

2007). Two hundred of Swadesh's basic vocabularies

is used because the vocabulary is in all languages

and unlikely to change.

Furthermore, research data obtained from

informants will be transcribed and compared with

data from research conducted in Bandung with the

same question list. In that comparison, the authors

sifted the data to find the Sundanese vocabulary that

was not used in Bandung but still found in the Badui

area. The research data used as comparative material

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

594

in this research is data from research entitled

“Pemetaan Bahasa di Kota Bandung Sebuah Kajian

Dialektologi” (Language Mapping in Bandung City:

A Dialectology Study) Sulyana (2012).

As the capital of West Java province and central

government, Bandung can be considered as a region

with more modern Sundanese language. By

comparing data on the use of Sundanese language

vocabulary in Badui territory which is considered

old-fashioned and data on the use of Sundanese

language vocabulary in Bandung area that is

considered more modern, researchers can discover

how many vocabulary words Sundanese undergoing

changes. Then, the filtered vocabulary is sorted

again based on an ancient Sundanese dictionary

entitled A Dictionary of the Sunda Language of Java

(Rigg, 1862). The author chose the dictionary as

reference material in this study because the

dictionary is considered as the oldest Sundanese

dictionary.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Based on data collection in the field using the 200

questions list of Swadesh's basic vocabulary, there

are 633 vocabularies used by Badui community.

From the entire vocabulary, as many as 47

vocabulary is not used in the area of Bandung and

contained in an ancient Sundanese dictionary.

Meanwhile, other vocabularies that is recorded is a

common Sundanese vocabulary that is still used in

other areas of West Java. The fifty vocabulary,

among others is as seen in table 1.

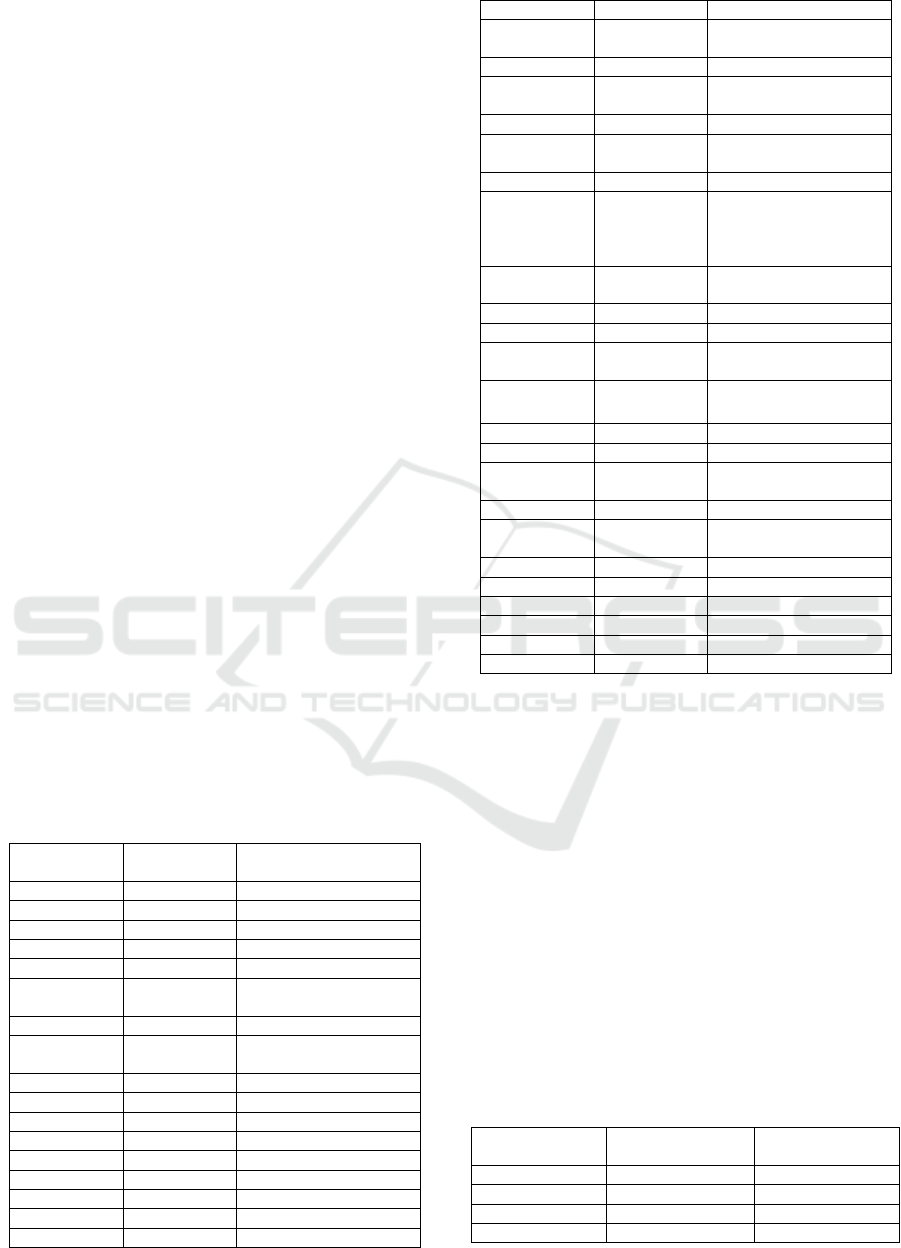

Table 1: Sundanese Archaic Vocabularies.

Swadesh Basic

Words

Vocabulary

New Vocabulary

ALIR (ME)

palid

ngalir, ngocor

APUNG (ME)

ngambul

ngambang

AWAN

ré-ék, halimun

awan, angkeub, méga

BAIK

éndah, bageur

hadé, saé, alus

BAKAR

huru

beuleum, duruk, bakar

BARING

ngedeng

ngagolér, golér,

gogoléran, saré, tiduran

BARU

kakarak

anyar, baru, éngal

BELAH (ME)

bencar

beulah, ngabeulah,

meulah

BENGKAK

kembung

bareuh

BERI

biken

méré, béré, masihan

BERJALAN

udag

leumpang, papah

BINATANG

satowa

sato, héwan, binatang

BURU (BER)

ngalanjak

moro

BURUK

bau

buruk, goréng, butut

CUCI

seseuh

kumbah, cuci

DANAU

dano

situ

DARAH

mokla

getih

DINGIN

tiris

ti’is, ngecep

GEMUK,

LEMAK

lintuh

lintuh, gendut, montok

GARUK

korék

gero

HANTAM

gebuk

hantem, nubruk, nabrak,

tubruk, neungar

HATI

angen

haté, ati

IBU

ambu

ibu, indung, ema,

mamah

IKAT

talian

tali, beungkeut

KARENA

kerna

karena, sabab,

kulantaran, lantaran,

saupami, upami,

kusabab

KATA (BER)

lémék

ngomong, nyarios,

nyarita

KERING

tuhur

garing

KOTOR

ledok

kotor

LEMPAR

balangkeun,

piceun, balang

balédong, malédog,

alung, téngor, ngalung

LIHAT

deuleu,

ngadeuleu

tingali, ningali, tingal,

tempo, malong

MAKAN

madang, nyatu

dahar, tuang

MATAHARI

matapoé

panonpoé

NYANYI

ngawih

ngalagu, nyanyi,

nembang, ngahaleuang

PANJANG

lojor

panjang

PEGANG

cokot

cekel, nyekel, ngepeng,

cepeng, nyepeng

PERAS

pereut

peres, meres, mereut

PEREMPUAN

bikang

awéwé, istri

POTONG

tuwar

potong, motong, teukteuk

SUNGAI

wahangan

walungan, susukan

TERTAWA

seuseurian

seuri, gumujeng

TIDUR

hé-és

saré, bobo’, kulem

The archaic words in table 1 are still affected by

the usage or level of Sundanese used by Badui

community. One of the constraints in this research is

a closed attitude of Badui people. That condition is

very not possible to taking the data with a focus on

one particular language level. Additionally, it has

suggested that Sundanese used by the Badui people

does not have any different speech levels indicating

social status (Ekadjati, 1980). This study has,

however, identified evidence to the contrary.

Meanwhile, the number of archaic vocabulary

most commonly found in the Balinbing village of

Outer Badui, followed by Cikeusik village of Inner

Badui, and Ciwaringin village of Outer Badui. Table

2 shows percentage of archaic vocabulary based on

the village.

Table 2: Percentages of archaic vocabularies by village.

Village

Amount of Archaic

Words

Percentage (%)

Cikertawana

17

33.33

Cibeo

18

35.29

Cikeusik

22

43.14

Cijengkol

19

37.25

Searching of Sundanese Archaic Words in Inner and Outer Badui

595

Cisadang

18

35.29

Cieurih

20

39.22

Cipaler

13

25.49

Cikopeng

12

23.53

Cisaban

18

35.29

Balinbing

24

47.06

Ciwaringin

21

41.18

Karakal

14

27.45

Kaduketug

16

31.37

Kompol

17

33.33

5 CONCLUSIONS

Based on this study, it was found 47 archaic

vocabularies that are not used anymore in Bandung

but still used in Badui area. The archaic vocabularies

found in the Badui area consists of several word

classes, there are 25 verb vocabularies, 11 noun

vocabularies, 10 adjectives vocabularies, and a

conjunction vocabulary. Moreover, the archaic

vocabularies are not only found in Inner Badui area,

which is considered more exclusive due to the strict

application of customary rules but also found in

Outer Badui area that is considered to have

contaminated by the outermost areas because the

application of customary rules is laxer.

REFERENCES

Ayatrohaédi, 1979. Dialektologi: Sebuah Pengantar, Pusat

Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa. Jakarta.

Ayatrohaédi, 2002. Penelitian Dialektologi, Pusat Bahasa

Departemen Pendidikan Nasional. Jakarta.

Chambers, J. K., Trudgill, P., 2004. Dialectology,

Cambridge University Press. Cambridge,

2nd

edition.

Djoewisno, M. S., 1987. Potret Kehidupan Masyarakat

Baduy, Khas Studio. Jakarta.

Ekadjati, E. S., 1980. Masyarakat Sunda dan

Kebudayaannya, Girimukti Pasaka. Bandung.

Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., Hyams, N. M., 2003. An

Introduction to Language, Thomson Wadsworth.

Boston.

Kompas Visual Interaktif, 2016. Baduy kembali, (Online)

Retrieved on 1 June 2017 from:

http://vik.kompas.com/baduykembali.

Lauder, M. R., 2006. Obstacles to Creating of Languages

in Indonesia’, In Cunningham, D., Ingram, D. E.,

Sumbuk, K., Language Diversity in the Pacific

Endangerment and Survival, Clevedon. England.

Lauder, M. R., 2007. Sekilas Mengenai Pemetaan Bahasa,

Akbar Media Eka Sarana. Jakarta.

Lubis, S., 2013. Loss of Words in Mandailingnese. Paper

presented to the International Seminar Language

Maintenance and Shift III.

Permana, R. C. E., 2006. Tata Ruang Masyarakat Baduy,

Wedatama Widya Sastra. Jakarta.

Rigg, J., 1862. A Dictionary of the Sunda Language of

Java, Lange & Co. Batavia.

Sodikin, 2006. Kearifan Lingkungan pada Masyarakat

Baduy, University of Indonesia. Depok.

Sulyana, F., 2012. Pemetaan Bahasa di Kota Bandung

Sebuah Kajian Dialektologi (Bachelor thesis),

University of Indonesia. Depok.

Wardhaugh, R., 2006. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics,

Blackwell Publishing. Oxford.

Yulis, E., Jufrizal, Ardi, H., 2013. An Analysis of Dead

Words of Minangkabaunese in Koto Tabang-Pariaman

Dialect. E-Journal English Language and Literature.

Retrieved on 1 June 2017 from:

http://ejournal.unp.ac.id/index.php/ell/article/view/239

8.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

596