Multidimensional Religiousness among Christian and Muslim

Students: Are There Gender Differences in Indonesia?

Riryn Sani

1

, Yonathan Aditya

1

, Ihan Martoyo

2,3

, Rudi Pramono

4

1

Department of Psychology, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Tangerang, Indonesia

2

Electrical Engineering Dept., Universitas Pelita Harapan, Tangerang, Indonesia

3

Reformed Theological Seminary Indonesia (STTRI), Kemang, Jakarta, Indonesia

4

School of Tourism & Hospitality, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Tangerang, Indonesia

Keyword: Multidimensional religiousness, Christian, Muslim, gender differences

Abstract: The idea of gender differences has been widely accepted as universal, also when it comes to religiousness.

However, evidences supporting this idea were mainly acquired using single or few items measurement. As

religiousness has been found to be multidimensional, at least in Christianity and Islam, the gender

differences need to be reinvestigated. Most studies in the subject of religiousness were done either in a

Christian populated or Muslim-based country, leading to the need of a more diverse samples in a cross-

cultural context. As one of the world’s largest Muslim nation, yet acknowledging religious pluralism,

Indonesia is a fitting population to serve the purpose. 331 Christian and Muslim college students with men

and women ratio of nearly 1:1 filled the Four Basic Dimensions of Religiousness (4-BDRS). T-test analysis

found no significant differences in religiousness between women (n=99) and men (n=92) in the Christian

samples. On the other hand, Muslim men (n=62) were found to have higher religiousness than women

(n=78) in total religiousness (t(138) = 2.455, p<0.05) and Bonding dimension (t(138) = 3.721,

p<0.0001).These results suggest a complex interplay between gender and religiousness, which involves

religious socialization phenomena, patriarchal culture, culture’s masculinity, and religiousness development

in university.

1 INTRODUCTION

The notion of gender differences is a popular

concept in modern society, with religiousness being

included in the scope of discussion (Bryant, 2007).

Scholars in psychology of religion commonly

accepted that women are more religious than men

due to numerous surveys that repeatedly found this

to be the case (Sullins, 2006). Women were found

having higher participation in religious affiliation

(Smith, Denton, Faris and Regnerus, 2002), greater

daily connection, more assurance and emotional

connection with God, compared to men (Buchko,

2004). This idea that women are more religious than

men became so universally apparent that study of

religiousness routinely includes gender as a control

variable (Stark, 2002).

Having said that, a point needs to be made about

the concept of religiousness used in previous

surveys, in which they mostly use single or few

items. Therefore, it seems evident that the claim of

gender differences needs to be confirmed with a

more thorough model of religiousness. A recent

model was introduced by Saroglou (2011), which

provides an integrative framework to study variation

of religious dimensions in the field of cross-cultural

psychology. In the multidimensional construct, the

coexistence of cognitive, emotional, moral, and

social dimensions correspond to the four

components of religion, respectively looking for

meaning and the truth (Believing), experiencing self-

transcendent emotions (Bonding), exerting self-

control to behave morally (Behaving), and belonging

to a group that solidifies collective self-esteem and

in group identification (Belonging) (Saroglou,

2011).

The multidimensionality of religion has been

acknowledged in Christianity and Islam (Abu-Raiya

and Pargament, 2011). Christianity displays

multidimensional religious motivation (Beck and

Jessup, 2004), and multidimensionality in their

specific religious values and beliefs (Snell and

Sani, R., Aditya, Y., Martoyo, I. and Pramono, R.

Multidimensional Religiousness among Christian and Muslim Students: Are There Gender Differences in Indonesia?.

DOI: 10.5220/0010058700002917

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Sciences, Laws, Arts and Humanities (BINUS-JIC 2018), pages 609-614

ISBN: 978-989-758-515-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

609

Overbey, 2008); likewise Muslims aspired to have

multidimensional religiousness that may be unique

compared to other religion (Raiya, Pargament,

Mahoney And Stein, 2008; AlMarri, Oei and Al-

Adawi, 2009). The majority of research in this field

utilized American and Iranian samples, therefore

future studies with more diverse samples are needed

given the significant geographical and consequently,

cultural differences in different places in the world

(Abu-Raiya and Pargament, 2011).

Indonesia is a country with religious pluralism,

with Muslims making up nearly 90% of its

population and 7% of the population identified

themselves as Christians (Subdirectorate of

Statistical Demographic, 2012). As one of the

world’s most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia

remains constitutionally secular, applying civil law

with citizens formally adhere to one of the six

official world religions (Pedersen, 2016). Previous

studies on religiousness in Indonesia were done

exclusively with either Muslims or Christians, with

the use of unidimensional measure in Muslim

population (Sallquist, Eisenberg, French, Purwono

and Suryanti, 2010; French, Purwono and

Triwahyuni, 2011) and initial use of

multidimensional measure in Christian population

(Saputra, Goei and Lanawati, 2017 ).

The present study was initiated to attest the

universally accepted notion of gender differences in

religiousness, using multidimensional model.

Considering the lack of study in this subject of

interest in a country that is not Christian populated

nor Islamic-based, Indonesia is a plausible setting to

answer the question. As result of Indonesia’s

pluralism in religious culture, it is possible to study

Christians and Muslims together using a cross-

cultural measurement.

In line with the seemingly consistent gender

differences in religiousness study involving

Christians, it is hypothesized that Christian women

will have higher religiousness than men. On the

other hand, Muslims with more patriarchal culture is

hypothesized to have the opposite result, where men

will have higher religiousness than women (Sullins,

2006).

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

The total participants who completed questionnaires

are 331 college students, with 191 Christians and

140 Muslims. The ratio of men and women are

nearly 1:1 with 92 men, 99 women; and 61 men, 78

women, representing Christian and Muslim sample

respectively. Participants were taken from two

Muslim universities, one Christian university, and

one non-religious university in Jadetabek (Jakarta,

Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi) area. Participants’

age ranges from 17 to 23 years old with the average

age of 19.2 years old. Participants’ ethnicity were

30% Chinese, 26% mixed, 21% Javanese, 7%

Sundanese, 6% Bataknese, 5% Betawis, and another

5% from Manado, Ambon, and Papuan.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Four Basic Dimensions of

Religiousness Scale (4-BDRS)

The scale was developed by Saroglou et al.

(Saroglou and 13 coauthors from the International

Project on Fundamentalism, 2012), consists of 12

items that measures four basic dimensions of

religiousness. The four dimensions refer respectively

to four components of religion: beliefs,

emotions/rituals, moral norms, and

group/community. Three items measure each

dimension of Believing (e.g., “I feel attached to

religion because it helps me to have a purpose in my

life”, “It is important to believe in a Transcendence

that provides meaning to human existence”),

Bonding (e.g., “Religious rituals, activities or

practices make me feel positive emotion”, “Religion

has many artistic, expressions, and symbols that I

enjoy”), Behaving (e.g., “I am attached to the

religion for the values and ethics it endorses”,

“Religion helps me to try to live in a moral way”),

and Belonging (e.g., “In religion, I enjoy belonging

to a group/community”, “Belonging to a religious

tradition and identifying with it is important for

me”). Each item was answered on a seven-point

Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly

agree). A total score for each dimension is calculated

with higher scores indicating higher involvement in

that specific dimension, and a total score from all

four dimensions represent indicator of total

religiousness. In the present study, internal

reliability measured with Cronbach’s Alpha were

.929 in the Christian sample and .885 in the Muslim

sample. The corrected item total-correlation for the

12 items in 4-BDRS ranges from .470 to .716 in the

Christian sample and .471 to .685 in the Muslim

sample.

BINUS-JIC 2018 - BINUS Joint International Conference

610

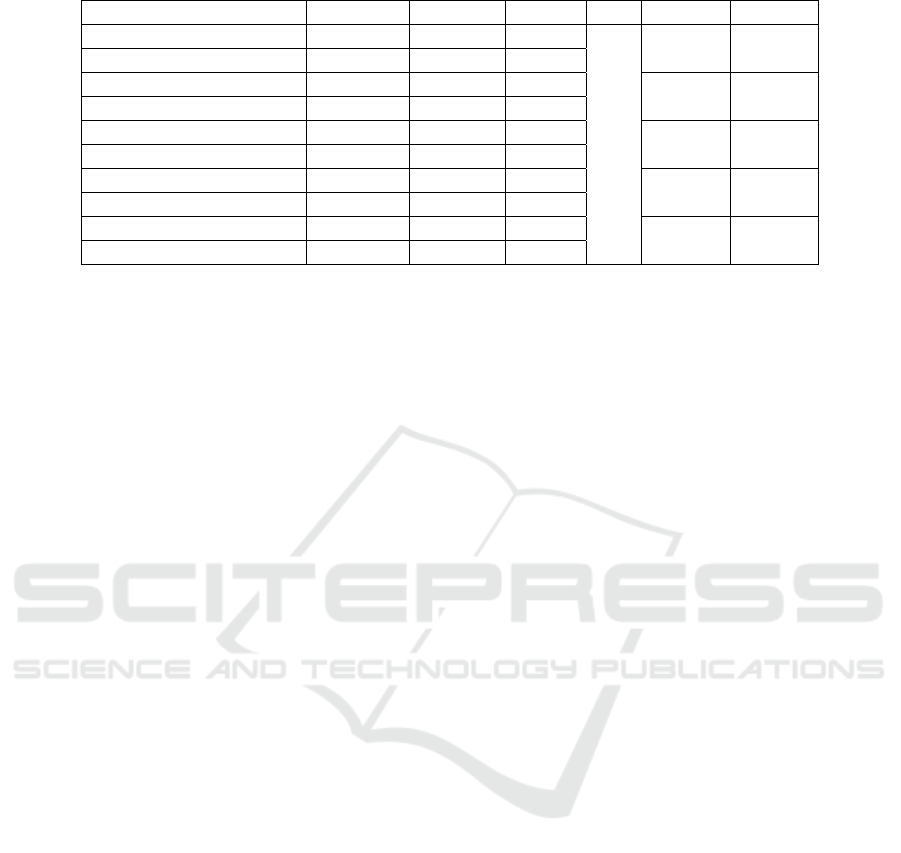

Table 1: Sample descriptive & t-test results of Christian Student.

M

SD d

f

t

p

Total reli

g

iousness Men 63.59 13.76

189

.32 .75

Women 64.18 11.78

Believin

g

Men 16.84 3.83

.50 .62

Women 17.09 3.2

Bondin

g

Men 15.36 3.86

.53 .60

Women 15.64 3.38

Behavin

g

Men 16.84 3.73

.08 .94

Women 16.88 3.3

Belon

g

in

g

Men 14.55 4.6

.04 .97

Women 14.58 3.75

a

M=Mean. SD=Standard Deviation. df=degree of freedom. t=result of independent sample t-test

3 RESULTS

Normality of the data distribution was interpreted

using skewness and kurtosis range suggested by

George & Mallery (George and Mallery, 2010),

which is ±2. All the data distributions being

analyzed had characteristic of kurtosis and skewness

of ±.7, much lower than the suggested range,

pointing to normal distribution. As assumption of

normality is fulfilled, independent sample t-test as

parametric test of comparing means between groups

was utilized.

Results presented in Table 1 show no significant

differences in all measures of religiousness of

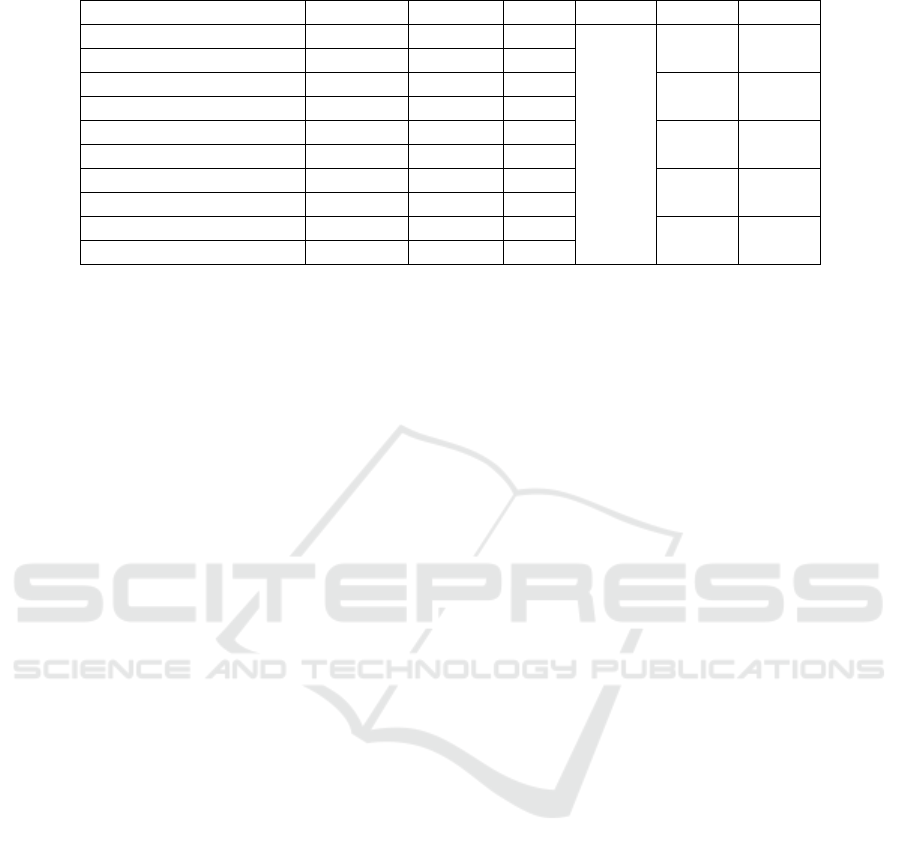

Christian students. In Table 2, Muslim male students

show a higher score in total religiousness, t(138) =

2.455, p<0.05, and Bonding dimension, t(138) =

3.721, p<0.0001, compared to the female Muslim

students.

4 DISCUSSION

The results of this study shed different light to the

notion of gender differences in religiousness. No

significant differences were found between Christian

male and female students, however the results for

Muslim students partially confirmed the hypothesis.

Albeit descriptively showing higher score in all

measures of religiousness, Christian women did not

differ significantly compared to men. This is

inconsistent with findings in America with

predominantly Christian samples (Smith, Denton,

Faris and Regnerus, 2002; Buchko, 2004). In the

Indonesian Christian sample, men and women do

not show significant difference in their degree of

cognitive understanding in religious ideology and

doctrine (Believing), transcendence in religious

rituals (Bonding), being virtuous in their religiously

guided moral actions (Behaving), and immersion in

religious community (Belonging). These findings

suggest that among Indonesian Christians, the

universally accepted gender differences in

religiousness do not apply.

The complexity of gender differences in

religiousness was first suggested by Sullins (2006).

His study cast serious doubt on the universal claim

that women are generally more religious than men.

He argued that the current explanation proposed to

reason for women’s superiority over men in

religiousness is too simple, therefore a better

understanding of religiousness interaction with

gender lies not in a search for universality but in the

acceptance of complexity. In pursuance of a better

understanding regarding the results among

(Indonesian) Christians, the present study will focus

on the distinctive characteristics of religiousness in

the sample, borrowing concepts from religious

socialization theory.

Religious socialization theory argues that

religiousness results from learning process

beginning in childhood and persisting until

adulthood with family as the socializing agents, both

nuclear and extended family (Bengtson, Copen,

Putney and Silverstein, 2009). In the context of the

Christian sample, men are said to be socialized more

into being a household’s leader having sets of values

pivotal to functional decision making; whereas

women are taught to support and submit to men by

preserving roles of nurturance and conflict

resolution (Frederick, 2010). In the context of

Christians in Indonesia, this might not be the case

any longer. More Christian families are seen

practicing dual-earner household, where women are

seen in the workplace, engaging in various

functional and leadership roles. It seems like more

Multidimensional Religiousness among Christian and Muslim Students: Are There Gender Differences in Indonesia?

611

Table 2: Sample descriptive & t-test results of Muslim Student.

M

SD d

f

t

p

Total reli

g

iousness Men 65.94 11.08

138

2.46* .02

Women 61.53 10.13

Believin

g

Men 17.68 3.41

1.90 .06

Women 16.58 3.4

Bondin

g

Men 16.42 3.0

3.72** .00

Women 14.41 3.3

Behavin

g

Men 17.81 2.62

.68 .50

Women 17.47 3.08

Belon

g

in

g

Men 14.03 4.32

1.43 .15

Women 13.06 3.67

* p<0.05, two-tailed

** p<0.0001, two-tailed

a

M=Mean. SD=Standard Deviation. df=degree of freedom. t=result of independent sample t-test

Christian women are being independent and not

fully supportive of the concept that women need to

submit to men. In other words, a differential

religious socialization might no longer be apparent

in (Indonesian) Christian men and women to cause

gender differences. Since there has yet to be data

and research to support this argument, further

elaboration is held from the present study.

Seemingly in line with the study’s hypothesis,

Muslim men show higher religiousness than women.

The previous religious socialization theory applies to

Muslims in a different way, with religious institution

replacing family as socializing agents, for example,

by practicing sex segregation in religious practice

and ritual, excluding women from religious

leadership. This practice in turn promotes strong

norms of masculine religious identity and ideals

(Sullins, 2006), thus explaining the significantly

higher total religiousness in Muslim men compared

to women. Another interesting finding is the

significantly different Bonding dimension between

Muslim men and women. Masculine religious

identity is rarely associated with emotional or

transcendence quality, but in explaining this finding,

the patriarchal culture in Muslim need to be

accounted. Masculinity in Islam men include the

essential ability to lead the whole family to Allah

(Siraj, 2010), where men are expected to be the

mediator between Allah and the rest of the family,

especially women.

One might argue that patriarchal value is not

unique to Muslims, since Christians in Indonesia are

applying it as well. The key difference here is the

strictly patriarchal practice among Muslims and

negotiable patriarchal practice among Christians. It

might be different case by case, but in most cases,

Christians practice patriarchy in moderation, for

example, it is common to see Christian women

becoming a pastor or a missionary while in Islam,

most religious affair needs to be executed under the

authority of men.

In his studies on the dimensions of culture,

Hofstede coined the term masculine vs. feminine

culture. A society is called masculine when

emotional gender roles are distinct. Men are thought

to be assertive, tough, focused on material success,

whereas women are expected to be modest, tender

and concerned with the quality of life (Hofstede,

Hofstede and Minkov, 2010). If both men and

women are expected to have more overlapping roles,

the culture is called feminine. According to

Hofstede, Christianity maintains a struggle between

masculine and feminine elements. The Old

Testament reflects tougher values and focuses more

on justice (an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth),

whereas the New Testament reflects more tender

values (turn the other cheek). In Islam, Sunni (the

majority Muslims in Indonesia) is a more masculine

version of faith than Shia (Hofstede, Hofstede and

Minkov, 2010). Hofstede’s theory of culture seems

to be consistent with the findings of this study,

which uncovered the fact that Muslim men are more

religious than Muslim women, whereas Christian

men and women do not show any significant

differences in religiousness.

The differences of religiousness development

between male and female students might be another

possible explanation of the study’s result. In

Christian female sample, a significant positive

correlation was found between age and total

religiousness (r = .228, n = 99, p = .023), Believing

(r = .302, n = 99, p = .002), and Behaving (r = .242,

n = 99, p = .016). In other words, Christian female

students’ religiousness, cognitive understanding in

religious ideology, and religiously guided moral

actions increased over their years in university.

BINUS-JIC 2018 - BINUS Joint International Conference

612

Similar correlations with age were not found in the

male student samples. Bryant (Bryant, 2007) found

that over time, female college students became

increasingly more likely than male to place

importance on integrating spirituality into their life.

Most participants in the present study were in their

freshman and sophomore year, when the said

difference between men and women were not

apparent. This factor might explain the absence of

gender differences in religiousness in Christian

sample.

Application of above results and explanations

require further confirmation due to the sample’s

conditions. Christian sample in the present study

was acquired from one Christian university while the

Muslim sample came from two Muslim universities

and one non-religious based university. Some

differences in religiousness aspect were found

between students who go to religious-based higher

education institution compared to those in secular

institution (Knecht and Ecklund, 2014). In the

present study, however, these possibilities could not

be clarified due to sample’s condition.

5 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

RESEARCH

This first study to test the notion of gender

differences in multidimensional religiousness found

interesting results. The universality of gender

differences is not to be taken for granted. Gender

differences in religiousness were not found among

Christians, while Muslim men show higher

religiousness than Muslim women in some areas.

Results differ from studies done in countries such as

America and Iran. This indicates that despite their

differences, Christian and Muslim in Indonesia are

similarly exposed to the country’s indigenous

quality. Understanding this will help sustain

religious peace among believers.

In this study, the complexity of gender

differences in religiousness is explained through

religious socialization theory, patriarchal culture,

Hofstede’s theory of masculine vs. feminine culture,

and gender differences in development of

religiousness in university. Nevertheless, the role of

Indonesia’s indigenous characteristics has not been

fully explained in the present study. In the future,

further studies about gender differences in

multidimensional religiousness are encouraged,

especially with a more representative sample’s

conditions. Efforts to ensure the psychometric

application of 4-BDRS as a cross-cultural

multidimensional measurement of religiousness in

Indonesia are urgently needed as well. The simple

psychometric data in the present study show

promising future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by the Indonesian

Ministry of Research and Higher Education No:

021/KM/PNT/2018, March 6, 2018; Kontrak

Penelitian Dasar Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi No:

147/LPPM-UPH/IV/2018.

REFERENCES

AlMarri, T.S.K., Oei, T.P.S. and Al-Adawi, S. (2009)

‘The development of the Short Muslim Practice and

Belief Scale’, Ment. Heal. Relig. Cult, vol. 12, pp.

415–26.

Abu-Raiya, H. and Pargament, K.I. (2011) ‘Empirically

based psychology of Islam: Summary and critique of

the literature’, Ment. Heal. Relig. Cult, vol. 14, pp. 93–

115.

Bengtson, V.L., Copen, C.E., Putney, N.M. and

Silverstein, M. (2009) ‘A longitudinal study of the

intergenerational transmission of religion’, Int. Sociol,

vol. 24, pp. 325–45.

Beck, R. and Jessup, R.K. (2004) ‘The Multidimensional

Nature of Quest Motivation’, J Psychol. Theol, vol.

32, pp. 283–94.

Bryant, A.N. (2007) ‘Gender differences in spiritual

development during the college years’, Sex Roles, vol.

56, pp. 835–46.

Buchko, K.J. (2004) ‘Religious Beliefs and Practices of

College Women as Compared to College Men’, J.

Coll. Stud. Dev, vol. 45, pp. 89–98.

French, D.C., Purwono, U. and Triwahyuni, A. (2011)

‘Friendship and the Religiosity of Indonesian Muslim

Adolescents’, J. Youth Adolesc, vol. 40, pp. 1623–33.

Frederick, T. (2010) ‘An Interpretation of Evangelical

Gender Ideology: Implications for a Theology of

Gender’, Theol. Sex, vol. 16, pp. 183–92.

George, D. and Mallery, P. (2010) SPSS for Windows step

by step: A simple guide and reference 17.0 update.

10

th

Edition. Boston: Pearson.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J. and Minkov, M. (2010)

Cultures and organizations: Software of the Mind.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Knecht, T., Ecklund, E. (2014) ‘Gender Differences at

Christian and Secular Colleges’, Christ. Sch. Rev, vol.

43, pp. 313–41.

Pedersen, L. (2016) ‘Religious Pluralism in Indonesia’,

Asia Pacific J. Anthropol, vol. 17, pp. 387–98.

Multidimensional Religiousness among Christian and Muslim Students: Are There Gender Differences in Indonesia?

613

Raiya, H.A., Pargament, K., Mahoney, A. and Stein, C.

(2008) ‘A psychological measure of islamic

religiousness: Development and evidence for

reliability and validity’, Int. J. Psychol. Relig, vol. 18,

pp. 291–315.

Sallquist, J., Eisenberg, N., French, D.C., Purwono, U. and

Suryanti, T.A. (2010) ‘Indonesian adolescents’

spiritual and religious experiences and their

longitudinal relations with socioemotional

functioning’, Dev. Psychol, vol. 46, pp. 699–716.

Saputra, A., Goei, Y.A. and Lanawati, S. (2017)

‘Hubungan Believing dan Belonging sebagai dimensi

religiusitas dengan lima dimensi well-being pada

mahasiswa di Tangerang’, J. Psikol. Ulayat, vol. 3, pp.

7–17.

Saroglou, V., et al. (2012) ‘Fundamentalism vs.

spirituality and readiness for existential quest: Do

religions and cultures differ?’, 21st Int. Assoc. for

Cross-Cult. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Psych.

Congress.

Saroglou, V. (2011) ‘Believing, bonding, behaving, and

belonging: The big four religious dimensions and

cultural variation’, J. Cross. Cult. Psychol, vol. 42, pp.

1320–40.

Siraj, A. (2010) ‘“Because I’m the man! I’m the head”:

British married Muslims and the patriarchal family

structure’, Contemp. Islam, vol. 4, pp. 195–214.

Smith, C., Denton, M.L., Faris, R. and Regnerus, M.

(2002) ‘Mapping american adolescent religious

participation’, J. Sci. Study Relig, vol. 41, pp. 597–

612.

Snell, W.E. and Overbey, G.A. (2008) ‘Assessing belief in

the 10 commandments: The multidimensional 10

commandments questionnaire’, J. Relig. Health, vol.

47, pp. 188–216.

Stark, R. (2002) ‘Physiology and faith: addressing the

“universal” gender difference in religious

commitment’, J. Sci. Study. Relig, vol. 41, pp. 495–

507.

Subdirectorate of Statistical Demographic (2012)

Population of Indonesia (Result of Indonesian

Population Census 2010). Jakarta: Statistics Indonesia.

Sullins, D.P. (2006) ‘Gender and religion: Deconstructing

universality, constructing complexity’, Am. J. Sociol,

vol. 112, pp. 838–80.

BINUS-JIC 2018 - BINUS Joint International Conference

614