Enhancing Intercity Relation among Secondary Cities in ASEAN

Baiq Wardhani and Vinsensio Dugis

Deptartement of IR Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

Keywords: ASEAN connectivity, secondary cities, regional integration

Abstract: This paper investigates the possible important roles of secondary cities in ASEAN to becoming pillars of

connectivity for ASEAN Community, the roles of which so far seems to have been still understudied. Our

arguments are based on three reasons. First, cities plays significant role in diplomacy since capital cities can

no longer to be sole players in world stage. Although at the beginning of the twenty-first century, foreign

affairs is still primarily a task of national governments and their ministries of foreign affairs (MFAs), the

state is no longer the only actor on the diplomatic stage. The foundations of diplomacy as such were

established long before 1648, when states did not yet exist and cities pioneered as foreign policy entities.

Second, diplomacy thus existed before the existence of states, but ASEAN has so far relied heavily in states

(capital city) to support inter-ASEAN relations and to forget that cities are oldest diplomatic actors. At a

time when ASEAN is gearing up for stronger integration, there is a need to enhance interaction among its

peoples to facilitate the vision of a solid regional community by 2020. One way to achieve it is through

enhancing the role of non-capital cities. Third, deepening ASEAN integration can be garnered through

strengthening the role of ASEAN’s cities.

1 INTRODUCTION

In September 2016, ASEAN Leaders adopted the

Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 (MPAC

2025) in Vientiane, Lao PDR. The Master Plan

focuses on five strategic areas: sustainable

infrastructure, digital innovation, seamless logistics,

regulatory excellence and people mobility. While the

new Master Plan succeeds the Master Plan on

ASEAN Connectivity 2010, it was also reported that

the New Master Plan was developed after

consultation with relevant ASEAN Sectoral Bodies

and other stakeholders (asean.org., 2016). It is

important to note, moreover, that many forms of

initiatives have been taken based on the MPAC 2010

(asen.org., 2016: 8). However, the adoption of the

MPAC 2025 indicates that more paths can be used in

order to achieve quality integration of ASEAN as a

community with one vision and one identity. This

paper argues for the possible important roles of

secondary cities in ASEAN to becoming pillars of

connectivity for ASEAN Community, the roles of

which so far seems to have been still understudied.

2 METHOD AND APPROACH

This article was based on a library exploration. Data

were mainly gathered from books, journal,

government reports, official reports from relevant

international organizations, and other related

information from mainstream media. In addition,

previous studies concerning the role of cities under

contemporary globalization were also consulted. The

data gathered then further qualitatively analyzed

using a framework that sees city as the new

economic geography (Roberts and Hohmann 2014)

where ASEAN connetivity project as a contect.

Report of the World Economic Forum in 2014

states that most productive of policy innovation is

not generated by the government at the national

level, particularly in international forums such as the

United Nations (UN), European Union (EU) and the

Group of 20 (G20), but it happens in cities and

subnational regions. Policy-making is done at the

municipal level, and thus the policies are generally

more flexible, practical and closer to the people, so

that is more conducive to practice. Cities manage to

learn from each other and adopt best practice that are

often better than that the one done by the state

(World Economic Forum Report 2014).

Wardhani, B. and Dugis, V.

Enhancing Intercity Relation among Secondary Cities in ASEAN.

DOI: 10.5220/0010277800002309

In Proceedings of Airlangga Conference on International Relations (ACIR 2018) - Politics, Economy, and Security in Changing Indo-Pacific Region, pages 397-403

ISBN: 978-989-758-493-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

397

Many cities in the world has substantially grown

to be more economical, it has international

connectivity, and plays diplomatic role on the world.

The emergence of the city as a transnational actor

thus not only driven by urbanization and

globalization, but also devolution. The end of the

Cold War was resulted many new countries (derived

from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the

disintegration of Yugoslavia), but also gave rise of

non-state actors in new form of sub-state, both the

city and the province that brought transparency,

identity, and connectivity, which translate a greater

autonomy. Issues such as climate change, economic

growth, counter-terrorism, are also problems not

specifically responsibility of the country’s leaders,

but also by the leaders of the city. Their ability to

respond to these issue indicate the current cities are

also grow into a diplomatic autonomous unit.

Along with the emergence of the city as an

important actor in the international relations, modern

cities are part of the new economic geography.

These cities are highly dependent on rapid

communication, trade, financial and investment

systems to support their development. However,

most of the global system and national city does not

benefit significantly from the ‘new era’ and the

economic geography of the city, instead benefited

from the secondary cities. Secondary cities were

able to play an important role as a catalyst and a

secondary hub in facilitating local production,

transportation, transformation, or transfer of goods,

people, trade, information, and services between the

system of sub-national, metropolitan, national,

regional, and global cities (Roberts and Hohmann

2014).

The highly important position of the city in the

geography of the new economy, the city is able to

form the ideology of civicism in post-national era,

placing people’s loyalty to the city beyond loyalty to

their nation-state. These has createsd a new kind of

an identity in a new level and establish new

institutions that exceed the limits of loyalty beyond

citizenship (Bell and Avner de -Shalit, 2011).

Globalization thus has given a greater role to the city

to become an important actor in international

relations due to the reduced role of the state. The

world's major cities became an important center of

various activities such as industry, trade, education,

and maritime, making the big cities, especially the

capital, became the center of urbanization. The rapid

urbanization in urban areas at a certain point resulted

in density and increased variety of social pathology

such as crime and poverty. The increasing trends of

negative symptoms lead to the reduced allure of the

capital, as the core city. Meanwhile, cities other than

the capital has played more critical role politically,

economically and culturally, to replace some part of

the capital city that has been saturated.

Using the analogy of the Immanuel Wallerstein’s

world system, Chase-Dunn and Hall (1997)

identified city into core and semi-periphery. Core

city is identified as the nation’s capital, a center

which forms range of activities. Semi periphery city

expands its network from periphery city toward a

larger form with new innovation and technology that

produce social change. This makes a semi-periphery

city which was originally has never been regarded as

a non-state actors, turned into one of the important

dynamics that engined as a center of globalization

from below. According Dezzani and Chase-Dunn

(2010), semi-periphery cities have the potential for

the emergence of new innovations that can

substantially change the scale and structure of the

city. Semi-periphery city has transformed itself into

a center of wealth and a hegemon as a result of

increased trade and commodity production.

2.1 Inter-ASEAN City Relations

In a post-state era, cities plays significant role in

diplomacy since capital cities can no longer to be

sole players in world stage. As ASEAN is gearing

up for stronger integration, there is a need to

enhance interaction among its peoples to facilitate

the vision of a solid regional community by 2020.

One way to achieve it is through enhancing the role

of secondary cities since these cities are increasingly

takes over the role of the capital cities in the global

economic. The United Nations estimates, by 2030

and beyond, medium and large cities (or ‘second-

tiers’, with a population of less than 5 million

people) will be an important part of economic

growth in many countries around the world,

particularly in developing countries (Chen and

Kanna 2012). This means that capital city (top-tier),

which is the center of the national economy for

thousands years shows a saturated market and less

attractive, both as a market and investment

destination. Second-tier cities are rapidly growing in

terms of foreign direct investment, export-oriented

production and services as well as increasing

domestic demand and government spending (Spire,

2010).

Inter-ASEAN city relations are not yet

considered as an integral part in developing a full

flag ASEAN Community, even though ASEAN has

emphasized the Vientiane Declaration on the

Adoption of Master Plan for ASEAN Connectivity

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

398

2025. The Master Plan underlines the need of

connectivity as the foundation to achieve the agenda,

which are “enhancing ASEAN Connectivity would

continue to benefit all ASEAN Member States,

through improved physical, institutional and people-

to-people linkages, by promoting greater

competitiveness, prosperity, inclusiveness and sense

of Community” (asean.org., 2016: 4). Furthermore,

the connectivity “encompasses the physical (e.g.,

transport, ICT, and energy), institutional (e.g., trade,

investment, and services liberalisation), and people-

to-people linkages (e.g., education, culture, and

tourism) that are the foundational supportive means

to achieving the economic, political-security, and

socio-cultural pillars of an integrated ASEAN

Community” (asean.org., 2016: 8).

This connectivity has been performed by

ASEAN citizens in their everyday lives in towns and

regions outside the capitals, in many ways, although

this has not been in the centre of high-profile

ASEAN discussion. Density and saturation in tier-1

cities prompted many companies to look for more

promising opportunities in second and third tier

locations. In many cases, companies find relatively

unexplored opportunities in these places. In recent

years, second-tier cities in Indonesia such as

Bandung, Surabaya, and Makassar, have shown

much faster growth rates than the capital city.

Thanks to the 2001 reform of the regional autonomy

law, provincial governments in second tier cities

have a more conducive business environment as a

result of greater autonomy in controlling local

income and collecting taxes. They are actively

pursuing foreign investors and businesses through

aggressive economic reforms.

2.2 Strengthening the Role of ASEAN

Cities

Strengthening cooperation among ASEAN cities are

important for many reasons. Indeed, capital cities

play an important role as they act as administrative

centres, hubs of economic, social and cultural

activity and symbolize the shared values of a state,

such as democracy, equality or development (Hall

1993 in Gilliland 2013). Typically, the capital cities

of ASEAN are the largest and busiest cities in the

states. In many cases, serve as metropolitan primacy,

ASEAN’s capital cities are overcrowd by the

problem of urbanization, and governing the capital

city involving the complex task of “providing

workable solutions to the employment, educational,

housing, transportation and recreational needs of the

millions” (Reed, 1967: 286). Mark Jefferson

introduced the concept of “primate city”, in which

according to him, the primate city is usually to

become “the national capital, a cultural center, the

focus of internal migration, a hub of nationalistic

ferment and the multi-functional nucleus of a

country's economy” (Reed, 1967: 287). However,

the multifunctional tasks and multiplicity function of

capital city is without limits. Many capital cities

have failed to perform its primary function due to

different types of unanticipated problems. ASEAN’s

capital city, Jakarta for example, has shown decline

in its performance due to problems including (i)

empirical issues such as pollution (surface water,

ground water, air), traffic congestion, floods, and (ii)

issues relating to climate change, spatial utilization

management (Mungkasa, n.d). Even big cities, like

London is not an exemption in showing evidence of

decline. Pike, et al (2016) assert, city decline in two

types, in absolute form (reduction in specific

indicators – such as population or employment) and

relative form (decline in a comparatively weaker

performance of a city on certain indicators in

relation to similar cities or to the national average).

Either decline in absolute or relative form, capital

cities has shown their limitations to provide

sustainable life for their populace.

In addition to that, as a regional organization,

ASEAN needs to boost the connectivity through

intercity relations. Deepening ASEAN integration

can be garnered through strengthening the role of

ASEAN’s secondary cities since this connectivity

may bring market closer that impacting to the

reduction of the economic density of the capital city.

Inter-ASEAN city connectivity will improve the

performance of, not only ASEAN Economic

Community, but also the other two ASEAN

community pillars: ASEAN politics and security and

socio-cultural pillar, hence improving people-to-

people connectivity as a whole. ASEAN community

is a breakthrough for ASEAN as a regional

organization. ASEAN has learnt that deepening

regionalization will only be achieved by involving

greater participation from its people through

‘globalization from below’ and lessening the elitist

approach. Looking back at the origin of the ASEAN

formation that the purpose of ASEAN is “…to

accelerate the economic growth, social progress and

cultural development in the region…”, evidently that

ASEAN is heading on the right track.

To enhance a people-to-people connectivity,

ASEAN needs to involve more intercity connection

as the basis of strengthening ASEAN community as

a whole. As has been stated elsewhere that cities,

more specifically secondary cities, play crucial role

Enhancing Intercity Relation among Secondary Cities in ASEAN

399

in shaping networks within ASEAN Connectivity

2025. ASEAN secondary cities have great potency

to materialize the connectivity. Primary cities are no

longer the main driver of economic prosperity. In

fact, newly urban centres, which considered as

‘sleeping giant’ have played pivotal role in

distributing wealth across Southeast Asia (Leggett,

2015: 20). A survey conducted by Nielsen NV and

AlphaBeta showcase that smaller cities in ASEAN

will compete with primate cities such as Jakarta,

Manila, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City and Singapore

in terms of consumption through to 2030. Moreover,

in terms of population, four cities will be important

centers of economic growth as a result of rural

migration to the cities, in where they register growth

of more than 50% up to 2025: They are: Samut

Prakan (Thailand), will expand by 62.3% from 2015

levels to 2.9 million; Batam (Indonesia) is predicted

to grow to 2.2 million; Vientiane (Laos) will grow

by 54.5% to 1.6 million; and Denpasar (Indonesia)

is likely to expand by 51.9% to 1.7 million (Boyd,

2017). Within ASEAN context, this development

cannot be ignored. Even though rural migration to

cities is not anew, ASEAN Economic Community

has provided a platform for increasing economic

performance through structural reforms.

2.3 Challenges

ASEAN people-to-people connectivity will be lived

up by the fact that population in secondary cities has

grown rapidly that marks a new urbanism. This fast

growing urban population is the engine of global

economic connections that help Southeast Asia to

become a centre of global economic activity. With

the increasingly strenuous task of primate cities, and

emphasizing division of labours between them,

secondary cities are able to take over a role as

connectors among hinterlands that the primate cities

have previously do. This is in parallel with the

structural reforms that have been happening in

almost all states in ASEAN by adopting the policy

of decentralization. Strengthening the role of

secondary cities at the regional level would not only

bring benefits to the cities, more importantly would

increased multi-level cooperation within ASEAN,

which reflect the success of regionalism.

Inter-ASEAN cooperation is the key of ASEAN

connectivity, but so far only a few efforts have been

made to facilitate it. List of twin cities/sister cities

among ASEAN cities (see list in Appendices)

showcase that little have been made to set up inter-

ASEAN city connection. Even though the list does

not comprehensively represent the quality, depth,

and form of the cooperation, the list showcase that

cooperation among ASEAN cities have lacked.

Instead, ASEAN cities have built intercity relations

with many cities outside ASEAN under the program

of twin towns or sister city. To Beal and Pinson

(2014: 303), the idea of twinning cities emerged as a

form of postwar reconciliation against the

background of the cold war in Europe and during the

1980s and 1990s, in the context of globalization, the

world witnessed a proliferation and a diversification

of cities’ international activities. They further

explain, twinning emerged alongside with other new

international activities that result in “a shift in cities’

international strategies, in terms of general

orientation and content”. This pattern occurred

globally, and thus placed mayors around the world

to play important roles. Mayors ‘new role’ have

expanded to diplomatic tasks, such as promoting

global economy and economic growth, facilitating

cultural exchanges, Networking extension and

international, cooperation development, and

representing the city at international organizations

(Zarghani, Ranjkesh, and Eskandaran, 2014).

Only if ASEAN to be more successful to achieve

its goal, a more “bottom up” approach is needed.

ASEAN Community would not be thriving without

involving cooperation among cities within ASEAN.

Indeed, ASEAN has developed programs which

involving cities as key factors in certain issues, but it

is still in its infancy step (see list in Appendice).

Some project have been initiated to connect cities in

ASEAN, such as ASEAN Smart Cities Network

(ASCN), where twenty-six cities from the 10

ASEAN countries have been named pilot cities for

the project (Chia, 2018). The ASCN comprises 26

pilot cities across all the ten ASEAN member

states: Bandar Seri Begawan, Bangkok,

Banyuwangi, Battambang, Cebu City, Chonburi, Da

Nang, Davao City, Jakarta, Ha Noi, Ho Chi Minh

City, Johor Bahru, Kota Kinabalu, Kuala Lumpur,

Kuching, Luang Prabang, Makassar, Mandalay,

Manila, Nay Pyi Taw, Phnom Penh, Phuket, Siem

Reap, Singapore, Vientiane, and Yangon (Thuzar,

2018). This is only an example that ASEAN cities,

secondary cities in particular, can play a prominent

role to shape regional integration. Town twinning or

sister city agreements among ASEAN member-

countries are a way to facilitate ASEAN

Community. Interaction among its populace is a key

to a stronger regional integration. Hence, those

agreements is has to be further develop. ASEAN

cities could create different initiatives and programs

which impact the whole of ASEAN citizens by

facilitating mobility, exchange, trade and

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

400

communication within the region and bring benefits

for all. Deepening intra-regional exchange and

facilitates cooperation at the urban level supports the

final goal of ASEAN Community.

3 CONCLUSION

In modern world, cities are changing and will

continue to change. Cities participate in almost

every stage of global politics. Cities began forging

links with other cities long before the rise of

Westphalian state. Their role, however have been

diminished as a result of the state-centric approach

in international politics. With the multi-functional of

states, sometimes it represents by capital cities

giving a rise for non-capital cities to centering

themselves to the socio-political, economic and

cultural stage.

Secondary cities have now emerged to become

important new non-state actors in the global politics

thanks to considerable decentralization have taken

place in many Southeast Asian countries. The wave

of democratization across the region that happened

two decades ago also paving a way to the role of

secondary cities to materialize ASEAN as a fully-

fledged regional integration. With 600 million

pepole and promising gross domestic product,

connectivity is crucial for the realization of ASEAN

Community. Secondary cities play important role to

enhance this connectivity since they assist to achieve

ASEAN Community goals. In conjunction with

decentralization policies adopted by the different

ASEAN governments, secondary cities became a

focus of policy makers to bring them into a major

role in stimulating activities in the regional

integration. The successful of deepening ASEAN

integration is still challenged, yet to be addressed by

the lack of cooperation among the region’s urban

areas.

REFERENCES

asean.org., 2016. Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity

2025. http://asean.org/storage/2016/09/Master-Plan-

on-ASEAN-Connectivity-20251.pdf

Beal, Vincent and Gilles Pinson, 2014. When Mayors Go

Global: International Strategies, Urban

Governance and Leadership. International Journal of

Urban and Regional Research. Volume 38.1 January

2014, pp. 302–317. DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12018.

Bell, Daniel A., and Avner de-Shalit. 2011. The Spirit of

Cities: Why the identity of City Matters in a Global

Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Boyd, Alan, 2017. Asean’s secondary cities poised to

boom. http://www.atimes.com/article/aseans-

secondary-cities-poised-boom/ Accessed 20/5/2018.

Chase-Dunn dan Hall (1997), “The Geography of World

Cities” in Robert A. Denemark (ed.). The

International Studies Encyclopedia. Chichester, UK:

WileyBlackwell Publishing.

Chen, Xiangming and Ahmed Kanna, 2012. Secondary

Cities and the Global Economy.

https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub/87/.

Accessed 20/5/2018.

Chia, Lianne, 2018. 26 cities to pilot ASEAN Smart Cities

Network

Read more at

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/26-

cities-to-pilot-asean-smart-cities-network-10183550

Accessed 12/5/2016

Gilliland, Anthony, 2013. Choosing the Federal Capital: a

Comparative Study of the United States, Canada, and

Australia. In: Klaus-Jürgen Nagel (ed.), The Problem

of the Capital City: New Research of Federal Capitals

and Their Territory. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis

Autonòmics.

Leggett, Regan, 2015. The Age of ASEAN Cities: From

Migrant Consumers to Megacities. Available from

http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/vn/

docs/Reports/2015/Nielsen-age-of-asean-cities.pdf.

Accessed 27/5/2016.

Mungkasa, Oswar Muadzin, n.d. Jakarta: Masalah dan

Solusi.

https://www.academia.edu/13256894/Jakarta_Masalah

_dan_Solusi

Pike, Andy, et al. 2016. Uneven Growth: Tackling City

Decline. York, UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Reed, Robert R., 1967. The Primate City in Southeast

Asia: Conceptual Definitions and Colonial Origins. In:

T.G. McGee (ed.), The Southeast Asian City: a Social

Geography of the Primate Cities of Southeast Asia.

New York: Praeger.

Roberts, Brian and Rene Peter Hohmann, 2014. Cities

Alliance. The Systems of Secondary Cities: the

Neglected Drivers of Urbanising Economies. CIVIS.

Roberts, Brian, 2014. Secondary Systems of Cities: Why

they are Important to the Sustainable Development of

Nations and Regions. Presentation to DFID, London.

Available from

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273442061_

secondary-cities_Presentation_DFID_14th_April.

Accessed 27/5/2016.

Spire, 2010. The Next Frontier in Asia: How Asia’s

second-tier cities are the world’s new marketing arena.

https://www.spireresearch.com/wp-

content/uploads/2012/02/the-next-frontier-in-asia.pdf.

Accessed 20/5/2018.

Storey, Donovan, 2014. Setting the Scene: The Rise of

Secondary Cities. Presentation for the Asia

Enhancing Intercity Relation among Secondary Cities in ASEAN

401

Development Dialogue: Building Resilience and

Effective Governance of Emerging Cities in ASEAN.

Singapore: Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy,

National University of Singapore. Available from

https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/docs/default-source/gia-

documents/asia-development-dialogue-storey-rev-

final-20140331.pdf. Accessed 27/5/2016.

Thuzar, Moe, 2018. "ASEAN Smart Cities Network:

Preparing For the Future".

https://www.iseas.edu.sg/medias/commentaries/item/7

447-asean-smart-cities-network-preparing-for-the-

future-by-moe-thuzar. accessed 12/7/2018

World Economic Forum, 2014. A Report of the Global

Agenda Council on Competitiveness The

Competitiveness of Cities.

Zarghani, M. J. Ranjkesh, M. Eskandaran, 2014. City

Diplomacy, analysis of the Role of Cities as the New

Actor in International Relations. Urban - Regional

Studies and Research Journal, Vol. 5 – No. 20 –

Spring 2014, pp. 33-36.

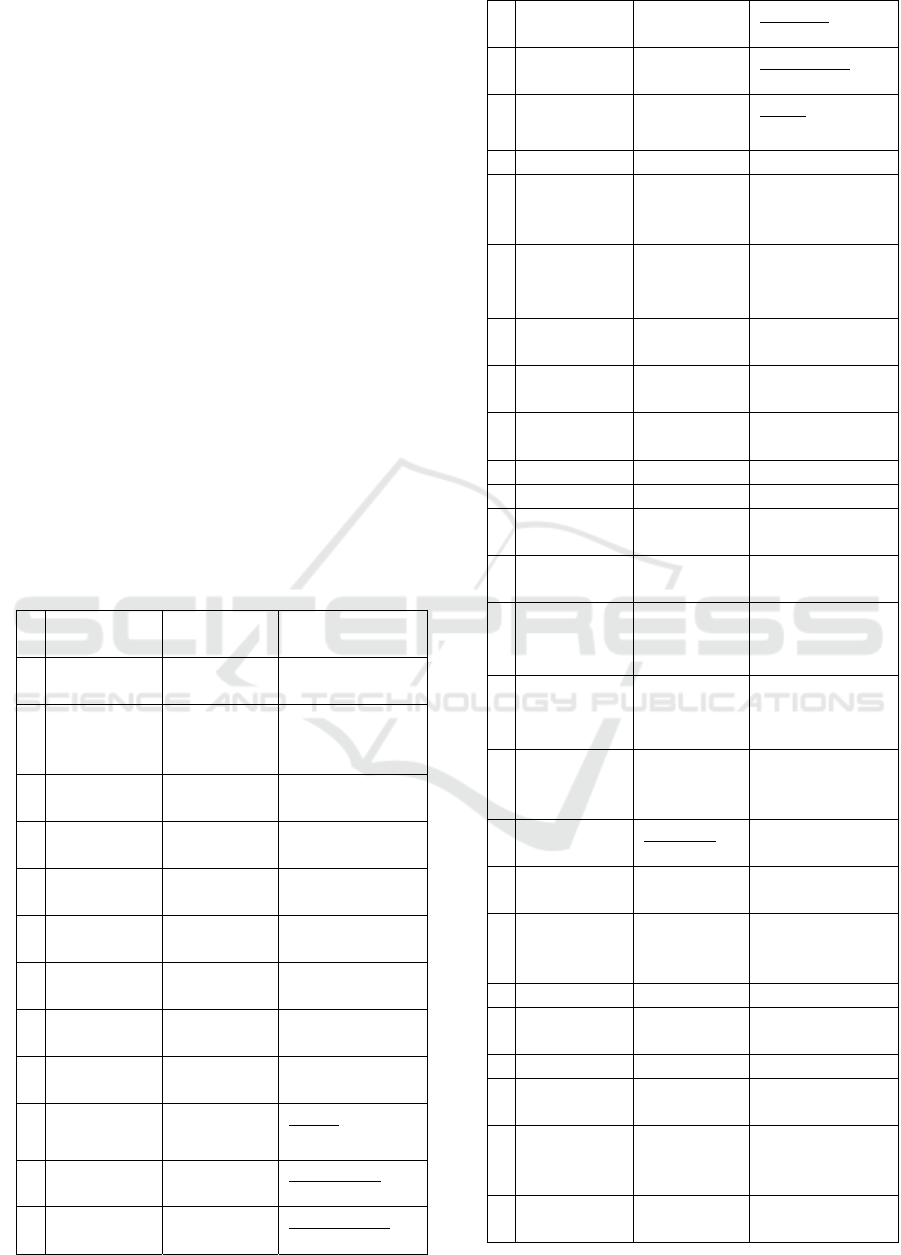

APPENDIX

List of Indonesia’s cities involving in twin

sister/sister city programs intercity in ASEAN and

outside ASEAN

N

o

Name of

cities

In ASEAN Outside

ASEAN

1 Banda

Aceh

Samarkand

(Uzbekistan

2 Medan Georgetow

n, Penang

(Mala

y

sia)

Apeldoorn

(Netherlands)

3 Bukittinggi Seremban

(Mala

y

sia)

4 Padang Vung Tau

(Vietnam)

Hildesheim

(German

y

)

Beit Lahiya

(Palestine)

Perth

(Australia)

Dubai (United

Arab Emirates)

5 Payakumbu

h

Nantong (PRC)

6 Sawahlunto Malacca

(Mala

y

sia)

7 Jakarta Berlin

(Germany)

Casablanca

(Morocco)

Los Angeles

(US)

Moscow

(Russia)

Pyongyang

(North Korea)

Seoul (South

Korea)

8Bo

g

o

r

Tainan, (ROC)

9 Bandung Petaling

Jaya

(Mala

y

sia)

Fort

Worth, Texas

(United States

Cotabato

(Filipina)

Braunschweig

(Germany)

Namur

(Bel

g

ium)

Cuenca

(Equador)

Liuzhou (PRC)

Yin

g

kou (PRC)

Shenzen (PRC)

Suwon (South

Korea)

Seoul (South

Korea)

Toyota City

(Japan)

Hamamatsu

(Japan)

1

0

Depok Ōsaki, Kagoshi

ma Prefecture

(Japan)

1

1

Semarang Da Nang

(Vietnam)

1

2

Surakarta Montana

(Bul

g

aria)

1

3

Yogyakarta Chiang

Mai

(Thailand)

Baalbek

(Lebanon)

K

y

oto (Japan)

Ismailia

(E

gy

pt)

Esvanza (Iran)

Prague (Czech

Republic)

Geongsangbuk-

Do (South

Korea)

Chungcheongn

am-Do (South

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

402

Korea)

T

y

rol (Austria)

1

4

Surabaya Seattle,

Washington

(US)

Guangzhou

(PRC)

Kaohsiung

(ROC)

Perth

(Australia)

Izmi

r

(Turke

y

)

Kochi (Japan)

Busan (South

Korea)

Liverpool (UK)

Xiamen (PRC)

1

5

Makassar Kuala

Terenggan

u

(Mala

y

sia)

Moskow

(Russia)

1

6

Denpasar Haikou (PRC)

Toyama

(Japan)

1

7

Singaraja Bacolod

(Philippine

s)

1

8

Ambon Darwin,

Northern

Territory

(Australia)

1

9

Papua Vanimo (Papua

N

ew Guinea)

Data is taken from various sources.

Enhancing Intercity Relation among Secondary Cities in ASEAN

403