How to Design Game-based Healthcare Applications for Children?

A Study on Children’s Game Preferences

A. F. A. de Vette

1

, M. Tabak

2

and M. M. R. Vollenbroek-Hutten

1

1

University of Twente, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science,

Telemedicine Group, P.O. Box 217, 7500 AE Enschede, The Netherlands

http://www.utwente.nl/ewi/bss

2

Roessingh Research and Development, Telemedicine Group, P.O. Box 310, 7500 AH Enschede, The Netherlands

http://www.rrd.nl/

Keywords: Gaming, Game-based, Game Preferences, Gamification, Game Design, Framework, Classification,

Taxonomy, Player Type, Telemedicine, ehealth, Health Informatics, Tailoring, Adherence, Engagement,

Children, Asthma.

Abstract: Game-based design can be used to develop engaging health applications for children. This engagement can

only be realised when design is tailored to their preferences. In this study we investigate game preferences of

children and translate these into design recommendations. Game preferences of children aged 6 to 12 were

assessed through a questionnaire. Outcomes were classified by means of the 7D framework which divides

game content into seven linear domains. Significant differences in mean scores among demographic

subgroups were explored. Sixty-five children participated (M=9 years, SD=0.24, 36 boys, 29 girls, 8 children

with asthma). Data showed high preference for content in domains novelty (M

novelty

=63) and dedication

(M

dedication

=70). Analysis resulted in subdivision of scores based on gender, age and playing frequency.

Striking differences in scores were found between boys and girls in discord (M

boys

=62, M

girls

=19), intensity

(M

boys

=60, M

girls

=27), rivalry (M

boys

=53, M

girls

=31) and threat (M

boys

=64, M

girls

=25). To design games for

children we recommend to stimulate curiosity by offering variation and discovery, to enable achievement,

learning and social contact. A divergence in preferences for boys and girls must be regarded. Opposed to

boys, girls may lose interest in games that have violent or scary content, that are mainly competitive or demand

continuous effort.

1 INTRODUCTION

Health informatics can bridge the distance between

healthcare professionals and enable patients to

receive treatment in their daily living environment

(Jansen-Kosterink, 2014), thereby alleviating the

increasing demand for care and improving the

autonomy and quality of life of patients. Despite that

such telemedicine applications contribute to positive

health outcomes (Huis in 't Veld et al., 2010),

adherence seems restricted to several weeks of

use(Tabak et al., 2014, Evering, 2013). Game-based

design may be a strategy to increase adherence as

introducing elements of game content to telemedicine

applications is hypothesised to better engage the

patient in using the application (Primack et al., 2012),

thereby facilitating underlying treatment objectives

(Baranowski, 2008). Moreover, applying game-based

design may be able to sustain engagement for a

prolonged time.

In order to successfully design game content that

appeals to a specific target group, an understanding of

their preferences regarding this game content is

essential. To express these preferences, we can

describe the user in various ways. Two commonly

used approaches are player taxonomies and game

genre (or form) classifications. A well-known player

taxonomy is the Bartle player typology (Bartle,

1996), which classifies players into four types that

represent the player’s preferred behaviour within the

game. Such player taxonomies like Bartle or e.g.

(Yee, 2005) usually originate from analysis of a

specific type of game and its players, and can

therefore not be generalised or used outside of their

context (Dixon, 2011). Also, the classes the models

consist of are fixed and non-linear, thereby not

422

Vette, A., Tabak, M. and Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.

How to Design Game-based Healthcare Applications for Children? - A Study on Children’s Game Preferences.

DOI: 10.5220/0006584804220430

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2018) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 422-430

ISBN: 978-989-758-281-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

forming a complete description of all preferences a

user may have. The other approach, expressing

preferences through game genre or form (such as a

simulation, shooter, educational, role-playing, etc.),

gives an overall representation of a set of game

features, which is not uniformly described among

various game developers (Apperley, 2006). Neither

of these approaches therefore allow for accurate

assessment of preferences that is needed to synthesise

into recommendations for the design of new game

content, as the information on the player from a

player typology is limited and too high level from a

genre classification.

Instead, particularly as we envision to add game

content to healthcare applications to prolong

adherence, information on the player’s preferences

needs to be more detailed. This would correspond to

a model that allows us to describe games by their

actual characteristics, which would enable us to

express preference of the user for specific game

content on a much more profound level. We expect

that by using such a model, we have more insight in

how the individual should be addressed through game

design but also how a group of users should be

approached to realise more engagement.

As such, we developed a model for the

classification of game content in earlier work (De

Vette et al., 2017); the ‘7D framework’. This model

can be used to assess and map the preferences of users

for game content, resulting in a detailed description

of these preferences that can be used to design new

content. The model can be used to gain insight in

whether or not demographic or psychosocial

differences exist that may have implications on the

design of the game content should be taken into

account. The 7D framework can also be used to

analyse and make explicit the content of existing

games. The theoretical foundations for this model

originate from the five factor model of personality

(McCrae and Costa, 2008) and its translation into

gaming semantics, the five domains of play theory

(Vandenberghe, 2012). The 7D framework structures

game content along seven linear domains that are

defined by a set of characteristics per each domain

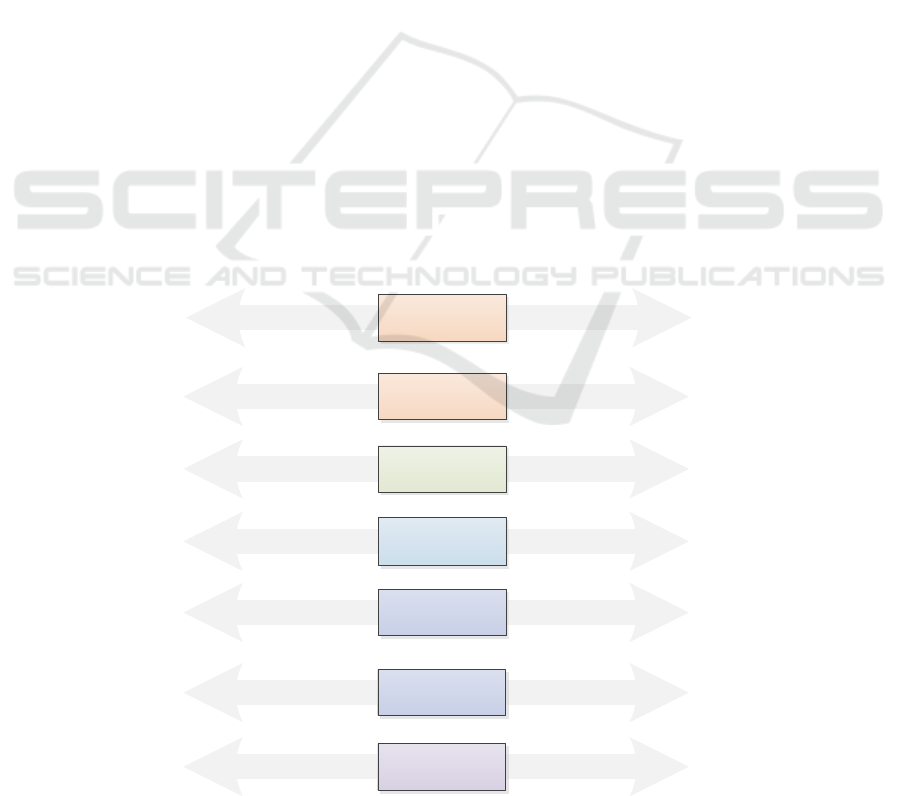

extreme, as shown in figure 1. Discord and rivalry

were originally represented by a single domain in

previous versions of the model, as were social and

intensity, hence they have been given the same colour

in the figure.

Applying the 7D framework and its precursors to

investigate the preferences of older adults group

showed, in short, their preference for high novelty

content and (cognitive) challenges, and an outspoken

disfavour for intense, violent and frustrating content

(De Vette et al., 2015, 2017). This research resulted

in the development of a game-based self-management

platform for older adults (De Vette et al., 2016) using

a storyline, enabling exploration, containing puzzle-

Figure 1: The 7D framework - a model for game content along seven linear domains.

RivalryCooperation Competition

+-

Novelty

Dedication

Discord

Threat

Habitual

Simplicity

Low self-discipline

Mastery

Achievement

Commitment

Teamplay

Altruism

Fairness

Compassion

Serenity

Gaining, winning

Defeating

Strife

Cruelty

Destruction

Intimidation

Low social engagement

Non-communicative

Company, social interaction

Communicative

Familiarity

Routine

Expectedness

Curiosity

Surprise

Fantasy

Social

Intensity

Pacifism Violence

Casual Devoted

Conventional Novel

Solitary Multi-player

Slow-paced Exciting

Calm Stressful

No time pressure

Short attention span

Low speed

Safety

Comforting

Pleasant

Fast

Intense

Thrilling

Frustration

Gloom

Tension

Domain

+-

Characteristics Characteristics

-

+-

+

+-

-

+-

+

How to Design Game-based Healthcare Applications for Children? - A Study on Children’s Game Preferences

423

oriented mini-games to sustain the motivation of the

user. This game is currently under evaluation to study

its effectiveness, but from preliminary results we find

that the translation of the user preferences into game

design has been successful. Now, we aim to explore

the use of this model to gain insight in the preferences

of other groups.

Unlike the older adult, children are a more

common consumer of video games making the

success of a game-based approach in healthcare

applications more likely. Games are regularly applied

for children outside the goal of entertainment, and

numerous examples of serious games (Charlier et al.,

2016) and game-based learning programs can be

found (De Sousa Borges et al., 2014). However,

additional research is needed to determine the game

design that best promotes effectiveness of games in

health informatics (Baranowski., 2015). Just like

older adults (De Vette et al., 2015), children do not fit

within the researched target groups using existing

user classifications, nor do these models fit the

context of digital healthcare applications. To the best

of our knowledge, we are unaware of an existing

framework that can be used to measure and elaborate

game preferences of children on the level of core

game content.

In this study we aim to gain insight in the

preferences of children regarding game content and

translate these preferences into design

recommendations for engaging game content for

children. To do so, we assess the preferences of

children along the 7D framework and research

whether significant differences in preferences exist

among subgroups of children. This could give us a

starting position in tailoring game-based telemedicine

applications to this target group.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design and Participants

The study is cross-sectional. The participants were

school-going children in the age of 6 to 12 years old.

Local primary schools were invited for a Science Day

taking place at University of Twente, the Netherlands.

During this day, children were taught about the

university and invited to participate in all kinds of

activities related to technological innovation.

Participants and their parents were informed on

beforehand about the activities of the Science Day by

the organisation of the event through an information

letter. In addition, a second group of children with

asthma within the same age range participated one

day later. These participants were recruited via the

children's department at Medisch Spectrum Twente,

Enschede. For both groups, parents gave their

informed consent prior to participation. Also,

children’s participation was voluntary and no

exclusion criteria were applied.

One of the activities was playing on an interactive

playground developed in the AIRPlay project

(Klaassen et al., 2017), to support self-management

of children with asthma and to promote their physical

activity in a fun and unobtrusive manner. This

playground uses floor projection and movement

tracking to generate the playing field for a game

inspired by the children’s game ‘tag’.

2.2 Measures and Materials

We assessed the preferences of children by using a

questionnaire based on the 7D framework. The

domains, as shown in figure 1, are 1) discord, which

features peaceful versus violent content, 2) rivalry

features cooperation versus competition, 3)

dedication the appreciation of a game that requires

low self-discipline (‘casual’) versus a game that is

achievement-oriented (‘devoted’), 4) novelty the

preference for conventional, routinely or real-world

versus fantasy, curiosity and variation, 5) social

features the opposition of the amount of interaction

with others, between solitary and multiplayer, 6)

intensity holds slow and relaxed against fast, intense

and time pressured, 7) threat the acceptable amount

of negative feelings that the game can cause in the

player, ranging from calm and lovely to frustration

and fear.

Each domain is a linear scale (ranging from 0 to

100) described by two extremes. These extremes are

described by characteristics, that can be translated

into actual game features. We deduce our

recommendations for game design from the measured

scores on the different domains, and on our analysis

of scores of identified subgroups.

The questionnaire was adapted to the target group

by keeping the questions concise and illustrating them

with simple images. Also, the number of questions

was limited to a minimum of 11 questions by

measuring two aspects of the more complex domains

of rivalry, dedication, novelty and social, and one of

the simpler domains intensity, threat and discord. All

questions were rated on a 1 to 5 scale, each question

was illustrated by two images of the extremes and an

example in text (fig. 2). The question was ‘Which

[example] do you like more in a game?’ (“I like

[example A] better than [example B]”). The average

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

424

scores were calculated for the seven domains and

expressed in terms of percentages.

Demographics, including information on

favourite games, playing behaviour and access to

devices, were assessed in the questionnaire.

2.3 Procedures

Measurements of both groups took place at

University of Twente and occurred in the same

manner. Groups of up to eight children were invited

to play on the interactive playground. The children

took turns in forming two teams of two players.

Playing continued for approximately five minutes.

Subsequently, the group of 8 participants was asked

to fill in the questionnaire.

2.4 Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Statistical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v.22). Data

distributions of the domains were analysed using the

Shapiro-Wilk test, descriptives and boxplots. All

domains were found non-normally distributed for all

participants. Results are presented as mean and

median domain scores. Subgroups were identified by

comparing mean scores and analysing significance

levels using the Mann-Whitney test for

nonparametric distributions.

The principal findings are presented in a visual

overview using the domain scores of all participant as

well as the most striking subgroup(s) based on the

highest number of significantly different domain

score means. Univariate linear regression analysis

was used to study the explained variance in the

domains by both gender and playing frequency.

3 RESULTS

Sixty-five children participated (mean age 9, 36 boys

and 29 girls). Table 1 shows the game preferences of

all participants. Subgroups were identified in

comparing means in gender, age and playing

frequency. This resulted in partitioning of gender in

1) boys and 2) girls, age in 1) 6 to 9 years old and 2)

10 to 12 years old, and playing frequency in 1)

frequent players (daily to at least weekly) and 2) non-

frequent players (not regular to never at all). A

trending difference (p < 0,10) was found between the

scores of children with and without asthma on the

domain novelty (M asthma = 47, M non-asthma = 65).

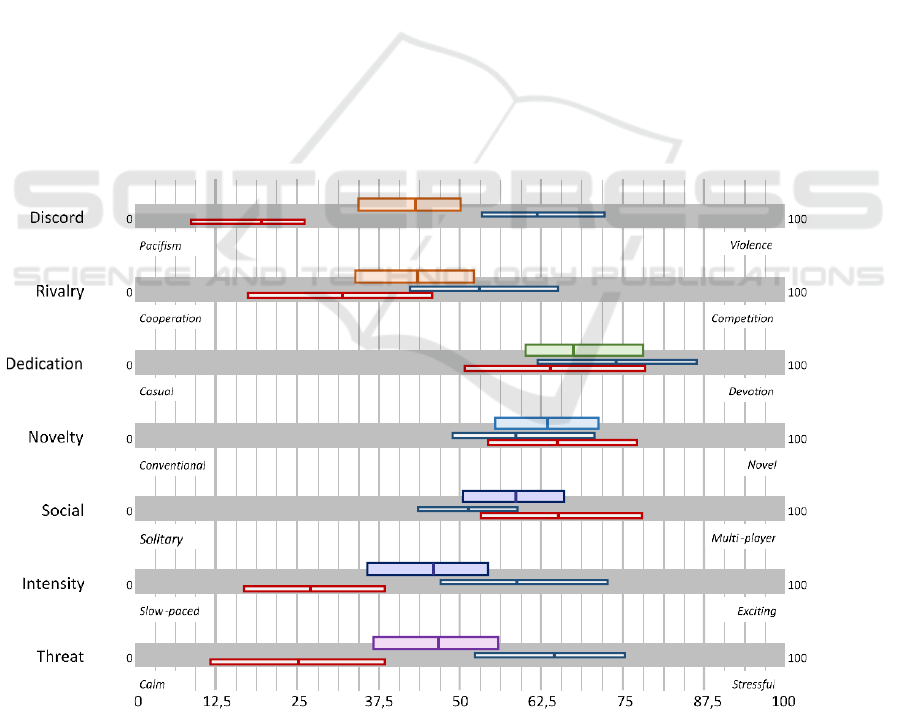

Figure 3 visualises the scores of all participants

and of boys and girls, as this subgroup shows the

largest number of significant differences. This graph

shows the uniformity in scores on dedication, novelty

and social, and the scores on discord, rivalry, intensity

and threat that appear to be determined by the clear

division in scores of boys and girls. The domains

dedication and novelty receive the highest scores

from all participants, indicating an outspoken

preference for content in these domains. The score on

dedication suggests that these children have a

preference for games that require effort and in which

goals can be achieved. The score on novelty suggests

a preference for variation, discovery, fantasy and

creativity instead of more predictable content, such as

football or racing. Significant differences were found

Figure 2: Fragment from the questionnaire (questions measuring intensity and threat).

How to Design Game-based Healthcare Applications for Children? - A Study on Children’s Game Preferences

425

between boys and girls on the domains discord,

rivalry, social, intensity and threat. Social

involvement through a game seems to be preferred by

girls more than boys. On average, girls indicate a

much different preference for discord, rivalry,

intensity and threat. On the scale of discord, in which

participants indicate their preferences between

peaceful and violent content, boys give a high and

girls a low score. A contrast of the same extent can be

found in intensity, that separates a relaxed activity

from one demanding focus and attention, and the

presence of time pressure and speed, and threat,

cheerful against disturbing content. Also in rivalry, in

which preference between working together and

competing as well as helping others to win against

defeating others is measured, boys indicated a much

higher preference for the latter.

A significant difference was found between the

means of the two age groups on the domain social (p

= 0,033). Upon analysis of the histograms of the two

age groups (data not shown) we find that the younger

group is more inclined to choose for the extremes

(values 1, 3 or 5) while the older group is capable of

indicating preferences on a more subtle level (also

using values 2 and 4). All except one participant, who

preferred playing alone, indicated to prefer playing

together with classmates, friends in the

neighbourhood or sports club and/or siblings or other

family members.

Significant differences in scores for different

playing frequencies were found in domains discord,

rivalry, intensity and threat (missing data for 8

children who did not answer this question). Frequent

players score on average about twice as high on these

domains than the less frequent players. 81% of boys

indicates to be a frequent player, of the girls this is

15%. However, there is a high significant correlation

between gender and playing frequency. Gender

shows to be a more important predictor for the

domain scores discord rivalry and threat than playing

frequency based on higher explained variance in

linear regression analyses, while playing frequency

was more important for the domain intensity (data not

shown). Subanalysis of the scores of frequently

playing boys (n = 25) and non-frequently playing

boys (n = 11) shows that their preferences differ on

the domain intensity (M frequent = 72, M non-

frequent = 34).

Looking into favourite devices and games of both

groups we see that children in the high playing

frequency group indicates to favour using consoles

such as PS4 to play games such as Call of Duty and

GTA, and children in the low playing frequency

group often do not indicate a specific favourite or

mention a website offering various mini-games. From

all participants, 14 children indicate a specific

console or PC game as their favourite game, 15

children mention Minecraft (5 of them girls).

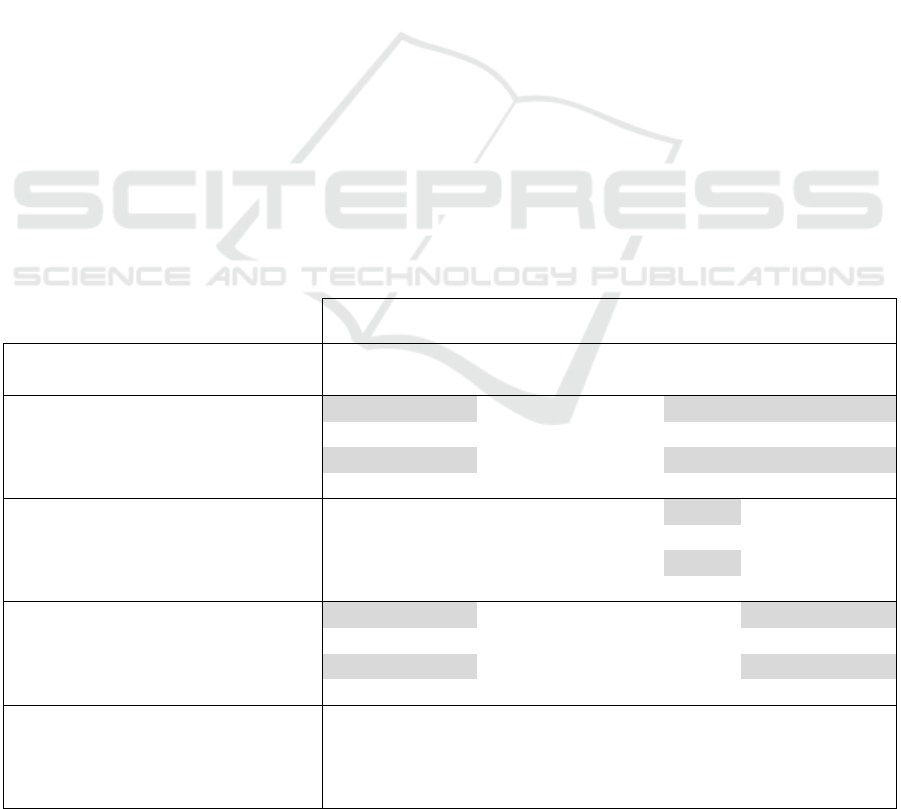

Table 1: Average scores on the seven domains (significant differences (α < 0,05) in means highlighted).

Discord

Rivalry

Dedication

Novelty

Social

Intensity

Threat

All (n = 65)

mean

43

43

70

63

58

45

47

median

38

50

75

63

50

50

50

Boys (n = 36)

mean

62

53

74

60

51

60

64

median

63

50

100

63

50

75

75

Girls (n = 29)

mean

19

31

65

66

66

27

25

median

13

25

75

75

75

25

13

6-9 years (n = 28)

mean

47

47

67

64

50

42

49

median

44

50

100

69

50

50

50

10-12 years (n = 31)

mean

38

39

73

61

66

49

44

median

38

50

75

63

75

50

50

Frequent players (n = 29)

mean

58

53

76

66

53

67

66

median

63

50

100

63

50

75

75

Non-frequent players (n = 28)

mean

25

34

64

64

64

26

30

median

25

25

75

69

63

25

13

Asthma (n = 8)

mean

48

41

69

47

55

34

34

median

63

25

63

50

50

0

25

Non-asthma (n = 57)

mean

42

43

70

65

58

47

48

median

38

50

75

63

50

50

50

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

426

4 RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings of this study we recommend the

following when aiming to engage children through

game design. These recommendations suit the

approach of designing one game to address the full

target group.

Novelty: Focus on Stimulating the Children’s

Curiosity and Avoid Routine.

New game content should be introduced regularly.

Variation can be created through for example new

rules, mechanisms or visual elements. Enabling

children to use their imagination, be creative and add

their own variations to the content, or enable

emergent gameplay, may be a valuable feature. A

novelty theme (fantastical, fictional) may also be

more suitable than a real-world theme.

Dedication: Provide Content that Enables

Achievement.

Games should always be sufficiently challenging. For

children, it may demand an effort to learn skills

necessary to play the game. A trial-and-error

approach to do so can be rewarding. Include clear

feedback on achievements. Making content

unlockable may serve both the preferences on novelty

and dedication.

Social: A Game Should Enable Playing Together.

The preference for social contact is slightly dependent

on the age and gender ratio of the group, but in

general children prefer playing together rather than on

their own.

Discord and Threat: A Neutral Approach Would

Be Advised on Violence and Scary Content.

We observed a preference for violent video games

particularly in boys. Most girls may be put off quickly

by for example fighting games, as most boys will

probably not be interested in overly cute games.

Violent and scary game content should always be age

appropriate.

Rivalry: Competition and Cooperation May Be

Used Alternately to Keep a Game Interesting for

Both Boys and Girls.

In a multiplayer game, team play or 'helper' functions

may be added next to mechanics enabling

competition, such as setting challenges for other

players.

Figure 3: Overview of preferences mapped on the 7D framework (average and 95% interval domain scores) of all participants

(top), boys (middle, blue) and girls (lower, red). The upper box in each domain shows the average score of all users and the

95% interval. The smaller boxes show the scores of boys (middle) and girls (lower) in the same manner.

How to Design Game-based Healthcare Applications for Children? - A Study on Children’s Game Preferences

427

Intensity: A Moderate Intensity Should Address

Both Boys and Girls.

We do however recommend keeping in mind the

preference for lower intensity of most girls. Games

should provide the opportunity to choose an intense

as well as a more laid-back playing style to avoid girls

losing interest from a game that demands continuous

effort, movement or focus. We believe that this is the

case particularly when developing games that involve

physical exercise.

5 DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to gain insight in the game

preferences of children, in order to synthesise

recommendations for game design to support the

development of engaging game-based telemedicine

applications. Using the 7D framework, the

preferences of 65 children were assessed resulting in

a graphical overview of preferences. The scores

suggest an overall approach towards game design for

this target group when attempting to engage all

members of the target group through one game, which

has been the basis for a set of game design

recommendations.

It is important to identify and take into account

different preferences from subgroups within a

population to avoid that game content is developed

that may either be too much of a compromise or is

disliked by the majority of one of both groups. While

gender was a more important predictor to game

preference in this study, we do not assume that we

should ignore playing frequency. We know that girls

are interested in games but that they prefer much

different characteristics (Kafai, 1998). The current

offer of videogames may determine that mostly boys

are the frequent players. There is a group of boys that

play frequently who indicated a much higher

preference for violent, intense and disturbing content

than the boys that play less often. Also, some have

access to consoles with games that may be considered

inappropriate for their age because of their violent

content. We expect that this subgroup may be hard to

please, if at all, as they are used to high-end games,

which moreover serve a set of preferences that may

put off many others.

Children with chronic conditions may form

another subgroup. Carefully interpreting the scores,

we expect that these children are more reserved

(lower novelty) and choose for a game that is less

intense (lower intensity). Recommendations for game

design for this group may include for example giving

them the chance to discretely take breaks or exhaust

themselves less than the others. More data is needed

to better understand the impact a chronic condition,

such as asthma, may have on game design.

Several aspects of this study lead to limitations

when generalising our findings for a greater public.

Firstly, our sample included children from local

primary schools. Cultural and educational differences

that may be of great influence on the results were not

taken into account. Divergent reading and writing

abilities among participants, not necessarily related to

age, may have led to misinterpretation of the

questions. Also, the Science Day and the playing on

the AIRPlay interactive playground may have

influenced the results. Secondly, validation of the 7D

framework is currently in progress. As such, the

creation of the questionnaire as well as the

interpretation scores into recommendations is to some

extent subjective. It is vital that the intention of the

designer is in accordance with the perception of the

target user on game content, future work should

include measures to align both frames of reference.

For example, a game designer may develop gameplay

that seems very intense for a child, while the child

itself interprets this differently. Furthermore, it

should be noted that the interpretation of the

recommendations given is open to the game designer,

as creating a satisfying game is not merely a sum of

parts but a design process in itself. As an example, a

high score on dedication indicates that it is more

likely that the user prefers game content that demands

devotion to play. This is described by the example

characteristics mastery, achievement and

commitment. In case of a high score on dedication,

we would recommend to include the need for skill

development in order to advance in the game (unlike

a more habitual game that would always require the

same amount of skill). A game designer may then

choose how to realise this aspect. Lastly, this study

included a limited number of participants with

asthma. We expect that minor differences will show

between the asthma and non-asthma group in a larger

dataset. At the time of writing the dataset is being

expanded with the data of more children with asthma.

In current and future work, we aim to fill in a

research gap on the existence of a method to elaborate

the preferences of any target group into a specific

characterisation to provide a starting position for

game-based design in health informatics. To ensure

validity of the 7D framework, we would propose to

extend research with 1) a comparison of the results

with existing literature on children’s playing

behaviour, preferences and personality, 2) creating a

more elaborate questionnaire that includes a larger

number of game content characteristics, as we assume

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

428

this can lead to more detailed recommendations for

game design, and to 3) apply the design

recommendations in practice to evaluate to measure

their effectiveness in engaging the target group to the

healthcare application. Furthermore, we aim to

investigate if certain domains are more important than

others to the overall engagement when developing a

strategy for game design. In future work we aim to

respond to any differences that may be found in

preferences for children with or without chronic

conditions, in order to predict which strategies may

be successful for these children based on game

preferences, besides attitude or different physical

capabilities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all participants and their

parents. This work was part of the AIRPlay project

(www.airplay.nl), financially supported by the

Pioneers in Healthcare Innovation Fund (PIHC round

2015). This fund (provided by University of Twente

and the hospitals Medisch Spectrum Twente and

Ziekenhuisgroep Twente) aims to facilitate the

introduction of innovative technology into the clinic.

REFERENCES

Jansen-Kosterink, S., 2014. The added value of

telemedicine services for physical rehabilitation.

University of Twente. [ISBN:9789082319606]

[PMID:17725187]

Huis in ’t Veld, RMHA., Kosterink, SM., Barbe, T.,

Lindegård, A., Marecek, T., Vollenbroek-Hutten,

MMR., 2010. Relation between patient satisfaction,

compliance and the clinical benefit of a teletreatment

application for chronic pain. J Telemed Telecare,

2010;16(6):322–8. [DOI:10.1258/jtt.2010.006006]

[ISBN:1758-1109 (Electronic)r1357-633X (Linking)]

[PMID:20798426]

Tabak, M., Brusse-Keizer, M., Valk, P. Van Der., Hermens,

H., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M., 2014. A telehealth

program for self-management of COPD exacerbations

and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized

controlled trial. International journal of COPD.

DovePress; 2014. p. 935–44.

[DOI:10.2147/COPD.S60179]

Evering, RMH., 2013. Ambulatory Feedback at Daily

Physical Activity Patterns: A Treatment for the Chronic

Fatigue Syndrome in the Home Environment?

University of Twente.

[DOI:10.3990/1.9789036535120]

Primack, B., Carroll, M., McNamara, M., Klem, M., King,

B., et al. 2012. Role of Video Games in Improving

Health-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review.

American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2012 vol: 42

(6) pp: 630-638.

Baranowski, T., Buday, R., Thompson, D., Baranowski, J.,

2007. Playing for Real: Video Games and Stories for

Health-Related Behavior Change. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine Volume 34, Issue 1, January 2008,

Pages 74–82.e10.

[DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.027]

Bartle, RA., 1996. Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades:

Players who suit MUDs. [URL:

http://mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm Archived at:

http://www.webcitation.org/6XvZlirzF]

Yee, N., 2015. Motivations of play in MMORPGs. Proc

DiGRA Conf Chang Views - Worlds Play 2005.

Dixon, D., 2011. Player Types and Gamification. CHI 2011

Work Gamification Using Game Des Elem NonGame

Context. 2011;12–5. [DOI:ACM 978-4503-0268-

5/11/05] [ISBN:9781450302685]

Apperley, TH., 2006. Genre and game studies: Toward a

critical approach to video game genres. Simul Gaming.

2006;37(1):6–23. [DOI:10.1177/1046878105282278]

McCrae, R., Costa, P., 2008. The Five-Factor Theory of

Personality. In: John OP, editor. Handbook of

Personality: Theory and Research, Guilford Press.

Vandenberghe, J., 2012. The 5 Domains of Play: Applying

Psychology's Big 5 Motivation Domains to Games.

De Vette, F., Tabak, M., Hermens, H., Vollenbroek-Hutten,

M., 2017. Mapping game preferences of older adults: a

field study towards a design model for game-based

applications. In progress.

De Vette, A.F.A., Tabak, M,. Hermens, H.J., Vollenbroek-

Hutten, M.M.R., 2015. Game preferences and

personality of older adult users. CHI PLAY

conference, London.

De Vette, F., Tabak, M., Hermens, H., Vollenbroek-Hutten,

M., 2016. Online gaming and training platform against

frailty in elderly people. Games for Health conference,

Utrecht.

Charlier, N., Zupancic, N., Fieuws, S., Denhaerynck, K.,

Zaman, B., Moons, P., 2016. Serious games for

improving knowledge and self-management in young

people with chronic conditions: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform

Assoc. 2016;23:230–9. [doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv100]

De Sousa Borges, S., Durelli, V., Macedo Reis, H., Isotani,

S., 2014. A systematic mapping on gamification applied

to education. Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM

Symposium on Applied Computing, March 24-28,

2014, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea.

[doi:10.1145/2554850.2554956]

Baranowski, T., Blumberg, F., Buday, R., DeSmet, A.,

Fiellin, L., Green, C., et al. 2015. Games for Health for

Children-Current Status and Needed Research. Games

Health J, 5( 1): 1–12. [doi:10.1089/g4h.2015.0026]

De Vette, F., Tabak, M., Dekker-van Weering, M.,

Vollenbroek-Hutten, M., 2015. Engaging Elderly

People in Telemedicine Through Gamification. JMIR

Serious Games, 3(2):e9, 2015.

How to Design Game-based Healthcare Applications for Children? - A Study on Children’s Game Preferences

429

Klaassen, R., Van Delden, R,. Cabrita, M., Tabak, M.,

2017. AIRPlay: Towards a ‘Breathgiving’ Approach.

Fitfth International Workshop on Behavioral Change

Support Systems (BCSS’17), Persuasive Technology

2017.

Kafai, Y., 1998. Video game designs by girls and boys:

variability and consistency of gender differences. In H.

Jenkins, & J. Cassell (1998) (Eds.), From Barbie to

Mortal Kombat (pp. 90-117). Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

430