Making AI Great Again: Keeping the AI Spring

Lito Perez Cruz

1

and David Treisman

2

1

Sleekersoft, 2 Warburton Crt., Mill Park, VIC 3082, Australia

2

C F Gauss & Associates, PO Box 652, Templestowe, VIC 3106, Australia

Keywords:

Artificial Intelligence, Deep Learning, Agents.

Abstract:

There are philosophical implications to how we define Artificial Intelligence (AI). To talk about AI is to deal

with philosophy. Working on the intersections between these subjects, this paper takes a multi-lens approach

in examining the reasons for the present resurgence of interest in things AI through a range of historical,

linguistic, mathematical and economic perspectives. It identifies AI’s past decline and offers suggestions on

how to sustain and give substance to the current global hype and frenzy surrounding AI.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today we are seeing an unexpected global buzz about

the benefits of Artificial Intelligence(AI), a phenome-

non absent a decade ago.There is a fervent and mas-

sive interest on the benefits of AI. Collectively, the

European Union through the European Commission

has agreed to boost AI investments

1

. The British go-

vernment, for example, is currently allocating 1 bil-

lion pounds to finance at least 1,000 government sup-

ported PhD research studies

2

. In its latest attempt to

provide meaning to the AI revolution and to prove it-

self as a leading source of AI talent , the French go-

vernment has recently unveiled its grand strategy to

build Paris into a global AI hub

3

.

The present response of governments to AI is a

stark contrast from the British governments reaction

following the Lighthill Report in 1973 which de-

picted AI as a mirage, criticizing its failure to achieve

its grandiose objectives (Lighthill, 1973). Years af-

ter that a decline in AI funding occurred. In that

era many AI scientists and practitioners experienced

trauma and shunned from identifying their products

as AI. They saw how businesses have not been keen

to the idea. Computer science historians call the de-

cline of AI funding and interest ”AI Winter”. Simi-

1

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release IP-18-3362 en.

htm

2

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tech-sector-

backs-british-ai-industry-with-multi-million-pound-

investment–2

3

https://techcrunch.com/2018/03/29/france-wants-to-

beco me-an-artificial-intelligence-hub/

larly, the call AI’s rise which is what we have today

as ”AI Spring”.

In this paper, we will identify the ”signal” from

the ”noise” (so to speak) by examining the present rise

of AI activity from various angels. We will argue that

having a clear definition of AI us vital in this analy-

sis. We do this by dealing with its historico-linguistic

career. We will show that indeed, the success pro-

vided by Deep Learning(DL), a branch of Machine

Learning (ML) which is itself a mini sub-category in

AI, is spearheading this rise in enthusiasm and in the

majority of cases this is what people mean when they

name-drop the AI label. We discuss the mathematical

features that contribute to its accomplishments. Next,

we will interject the idea of agency and ontology in

AI concepts which the public is uninformed about but

are considered by AI researchers important in having

a robust AI product. We then take a lesson from eco-

nomics and finally wrap our discussion with sugges-

tions on how we, as a community, can deflect another

AI winter and sustain the present AI interest.

2 THE AI TERM: A

HISTORICO-LINGUISTIC

ANALYSIS

What is intelligence? It is obvious, philosophers, psy-

chologists and educators are still trying to settle the

right definition of the term. We have definitely know

some notion of it but defining it into words is easier

said than done. For example, the dictionary says it

144

Cruz, L. and Treisman, D.

Making AI Great Again: Keeping the AI Spring.

DOI: 10.5220/0006896001440151

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence (IJCCI 2018), pages 144-151

ISBN: 978-989-758-327-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

is ”the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and

skills”. This is too broad. Because of this imprecision

in identifying human intelligence, we face the same

dilemma when it comes to machine intelligence, i.e.,

AI. Of course, all are aware that Alan Turing was one

of the first people who asked if machines could think.

Yet, it has been recognized that AI’s goals have often

been debatable, here the points of views are wide and

varied. Experts recognize this inaccuracy and they

do rally for a more formal and accurate definition

(Russell, 2016). This ambiguousness, we believe, is a

source of confusion when AI researchers see the term

used today (Earley, 2016) (Datta, 2017).

If a computer program performs optimization,

is this intelligence? Is prediction the same as in-

telligence? When a computer categorizes correctly

an object, is that intelligence? If something is

automated, is that a demonstration of its capacity

to think? This lack of canonical definition is a

constant problem in AI and it is being brought again

by computer scientists observing the new AI spring

(Datta, 2017).

Carl Sagan said,”You have to know the past to un-

derstand the present” and so let us apply this rule by

studying the history of the AI term so that we may see

why AI is suddenly getting very much publicity these

days.

John McCarthy, the inventor of the LISP program-

ming language, in 1956 introduced the AI term at a

Darthmouth College conference attended by AI per-

sonalities such as Marvin Minsky, Claude Shannon

and Nathaniel Rochester and another seven others

of academic and industrial backgrounds (Russel and

Norwig, 2010), (Buchanan, 2006). The researchers

organized to study if learning or intelligence, ”can be

precisely so described that a machine can be made

to simulate it” (Russel and Norwig, 2010). At that

conference, the thunder came from the work demon-

strated by Allen Newell and Herbert Simon with J.

Clifford Shaw of Carnegie Mellon University on their

Logic Theorist program (Flasinski, 2016) (Russel and

Norwig, 2010). This program was a reasoner and was

able to prove most of the theorems in Chapter 2 of

Principia Mathematica of Bertrand Russell and Al-

fred North Whitehead. Being in the field of foundati-

ons of mathematics, many hoped that all present mat-

hematical theories can be so derived. Ironically they

tried to publish their work at the Journal of Symbolic

Logic but the editors rejected it, not being astounded

that it was a computer that derived and proved the the-

orems.

Though it was in 1956 when the term was used,

the judgment of the community is that as far back

as 1943, the work done by Warren McCulloch and

Walter Pitts in the area of computational neuroscience

is AI (Russel and Norwig, 2010). Their work entitled

A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous

Activity (McCulloch and Pitts, 1943) (Russel and

Norwig, 2010) (Flasinski, 2016) proposed a model

for artificial neurons as a switch with an ”on” and

”off” states. These states are seen as equivalent to

a proposition for neuron stimulation. McCulloch

and Pitts showed that any computable function can

be computed by some network of neurons. The

interesting part is that they suggested these artificial

neurons could learn. In 1950, Marvin Minsky and

Dean Edmonds inspired by the former’s research on

computational neural networks (NN), built the first

hardware based NN computer. Minsky later would

prove theorems on the limitations of NN (Russel and

Norwig, 2010).

From the above developments we can see that over

optimistic pronouncements emerged right at the in-

ception of AI. Such type of conduct bears upon our

analysis below.

3 AI PARADIGMS AND DEGREES

3.1 Symbolic vs Connectionist

Going back to Section 2, we may observe the follo-

wing. The group gathered by McCarthy proceeded to

work on the use of logic in AI and is consequently

called by some as the Symbolic approach to AI.

Authors have called this view Good Old Fashion

AI (GOFAI). Most of these people apart from Min-

sky, worked on this field and for a while gathered

momentum primarily because it was programming

language based and due to the influence of Newell

and Simon’s results. Those working on NN were

called Connectionists since by the nature of networks,

must be connected. These groups continue to debate

each other on the proper method for addressing the

challenges facing AI (Smolensky, 1987).

This distinction in approaches should come into

play when the AI term is used but hardly is there an

awareness of this in the media and the public.

3.2 Strong or Weak AI

In 1976, Newell and Simon taught that the human

brain is a computer and vice versa. Hence, anything

the human mind can do, the computer should be able

Making AI Great Again: Keeping the AI Spring

145

to do as well. In (Searle, 1980), Searle introduced

Strong AI versus Weak AI. Strong AI treats the

computer as equivalent to the human brain or the

”brain in the box”. Therefore, Strong AI implies that

the computer should be able to solve any problem.

This is also called Artificial General Intelligence

(AGI).

On the other hand, Weak AI considers the computer

as a device geared up to solve only specific or

particular tasks. Some call this Narrow AI.

We believe unawareness of this distinction can

be a source of confusion when one says that a

product has AI. As an example, a search in LinkedIn

on the term ”artificial intelligence” will show the

term is used in articles or posts with no distinction.

Somehow these ideas get lost in the ”translation”

each time the AI term is utilized.

4 THE RISE AND FALL OF AI

From 1952-1969, AI researchers were scoring

success points. For example, Newell and Simon

extended their Logic Theorist to General Problem

Solver (GPS) which can solve puzzles. This program

mimicked the way a typical human might proceed

in solving a problem or task, such as establishing

sub-goals and planning possible actions. The AI

community at that time were filled with people

trained in the STEM discipline and for them to see a

program prove theorems, knowing that this process

involves creativity and imagination, certainly were

impressed when Herbert Gelernter produced his

Geometry Theorem Prover. Seeing a computer play

checkers and beat its human opponent created a

strong impression. The symbolic AI proponents do-

minated this phase of AI history and their enthusiasm

was at boiling point high. It is at this stage that AI

scientists receive funding for their research.

Back in 1957 people saw then that computers

occupied a floor with no monitors for data entry. Ima-

gine you hearing Herbert Simon say there are now

in the world machines that think, that learn and that

create. Simon also said that within 10 years of that

time, computers would play chess and prove signi-

ficant mathematical theorems (Russel and Norwig,

2010). Simon was not wrong on what the computer

can do, but was wrong with the time, he was too op-

timistic. This finally happened 40-50 years after his

statement.

We note that at this stage, the connectionists were

also gaining ground with their idea of the perceptron,

the precursor to NN.

(Russel and Norwig, 2010) mark 1966-1973 as

the first fall of AI or what may be called the first AI

winter. In 1973, the famous report by the British

government known as the Lighthill report shot and

burst the lofty balloon of AI (Lighthill, 1973). It

lambasted promoters of AI. We can characterize the

cause of disappointment due to the following:

• Fooled by novelty. The computer playing chess

and proving theorems is quite remarkable for

those who understand the challenge of doing this,

but can we transfer this principle to something

practical and useful? Perhaps like translating Rus-

sian documents to English? Here AI at this point,

failed.

• Problem of Intractability. AI life oriented pro-

blems are often characterized by a wide search

space trying out possible solution pats. Thus, this

went game playing. The search process takes a lot

of computing cycles which were then too slow to

provide timely answers.

We can add here the other factor of having

high hopes for the perceptron which have proven

by its own proponent (Minsky and Papert) that it

lacked expressivity as a source of intelligent behavior.

In the late 1970s expert systems began to rise

and brought a lot of success. One can legitimately

consider them Weak AI. Again, it came from the

work of symbolic AI scientists who worked on kno-

wledge representation systems(KR). AI experienced

new life in the early 1980s. However, after this, it fell

again the second time because they failed to deliver

on over-hyped promises.

It seems when AI experiences success, AI enthu-

siasts get carried away making unbridled promises of

what it can do and deliver, e.g., the famous Andrew

Ng tweeted that radiologists will soon be obsolete

(Piekniewski, 2018). Though the critic might be

against AGI, it affects negatively Weak AI as well.

Thus, it is the Strong AI proponents who is the

source of AIs rise and also its cause for a down fall.

We see this when Google’s DeepMind AlphaGo

4

beat its first human opponent in the game of Go. Im-

mediately we have experts saying it is now time to

embrace AI with an expert saying AI will surpass hu-

man intelligence in every field. It will have super-

intelligence (Lee, 2017). We are not advocating AI

4

https://deepmind.com/research/alphago/

IJCCI 2018 - 10th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence

146

phobia, not at all, but this assertion borders on tabloid

fodder. Of course, a computer will beat a human in a

game like Go. For one thing, humans get tired, they

carry personal anxiety and family issues to the game,

they could be suffering some illness as they play etc.

Humans have many forces that can distract their con-

centration; but computers do not have any of these. So

for sure, a computer will beat a human when it comes

to game playing.

In short, who brought down AI? Well, in a way

the AI researchers themselves through their over the

top advertisements of what can be achieved by their

research. There are severe lessons we can learn here.

5 SPEARHEADING AI

5.1 Is It Deep Learning?

When did AI become mainstream? When did it make

a comeback? Following the idea of the Gartner Inc.’s

hype cycle we may depict its rise, fall, rise and fall

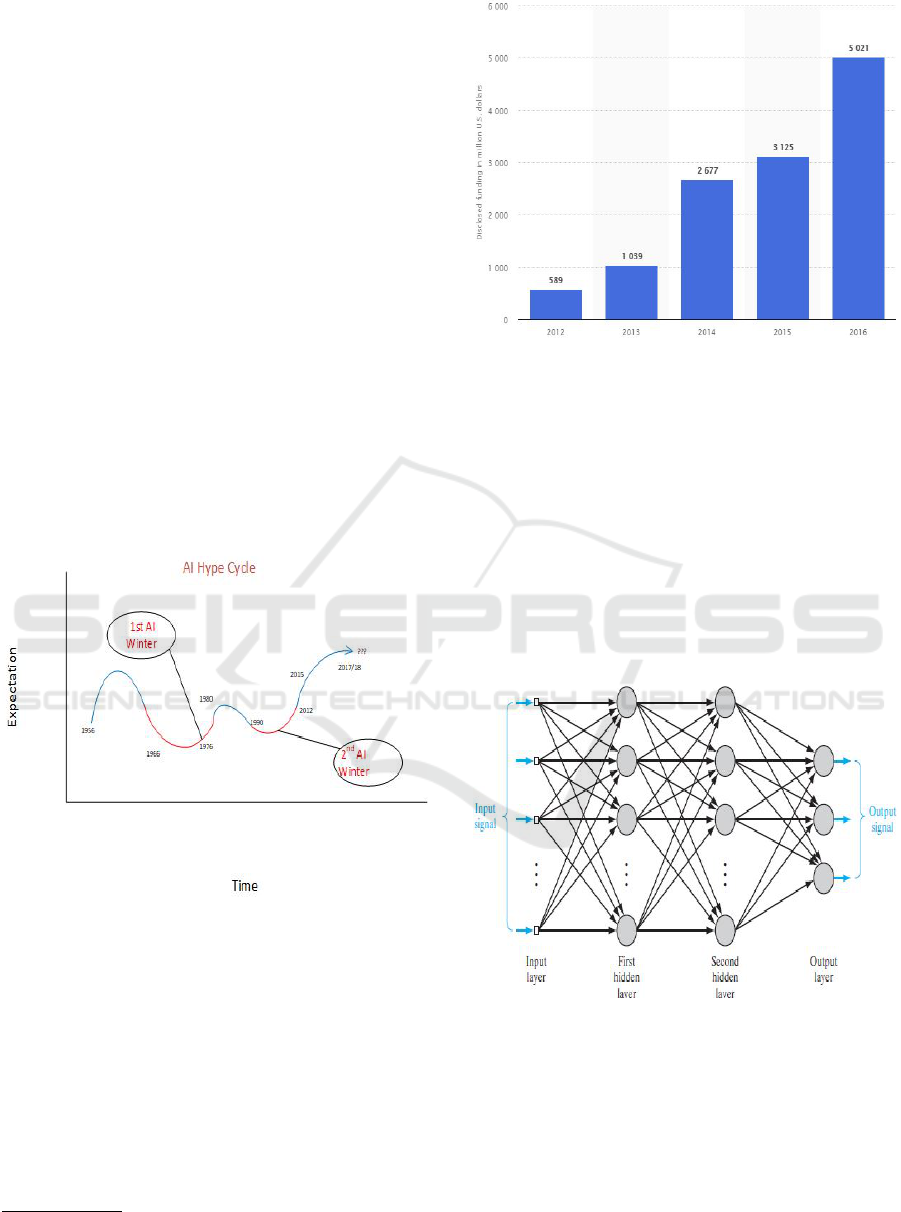

again by the picture in Figure 1.

Figure 1: AI’s present hype cycle.

The media are divided on this. Some observed its

comeback in 2015 (Ahvenainen, 2015). Others be-

lieve it came to the mainstream in 2016 (Aube, 2017).

However, there appeared to be a silent creeping in

of AI as far back as 2012 if we look at the funding

increase in AI that happened world wide we see this in

Figure 2 which comes from Statista

5

Note the steady increase starting from mere $0.5B

in 2012 to $5.0B in 2016. This is an incredible jump

in funding. Indeed, this is an astoundingly massive

5

https://www.statista.com/statistics/621197/worldwide-

artificial-intelligence-startup-financing-history/

Figure 2: AI Funding in Millions by Statista.

increase. In the same site we can read that it is

projected that in 2018 the global AI market is worth

about $4.0B with the largest revenue coming from AI

applied to enterprise applications market.

The press observe that it is Deep Learning(DL)

that is carrying the torch for AI (Aube, 2017), (Ahve-

nainen, 2015). Starting from the idea of artificial

neural network(ANN) from (McCulloch and Pitts,

1943), we best understand DL by referring back to

its multilayer version. The diagram of a multi-layer

ANN in Figure 3 is from (Haykin, 2008).

Figure 3: Multylayer ANN.

For convenience in space, we refer the reader to

the details found in works like that of (Haykin, 2008)

or (Bishop, 2006). We consider an ANN with two

layers. Assume that the linear combination of input

variables are called x

1

, x

2

, ...x

D

and going into the first

hidden layer with M neurons we get the output acti-

vation

a

j

=

D

∑

i=1

w

(1)

ji

x

i

+ w

(1)

j0

(1)

Making AI Great Again: Keeping the AI Spring

147

The w

(1)

ji

are the parameter weights and w

(1)

j0

are

the biases with the superscript (1) designating the first

hidden layer. They then get transformed by an activa-

tion function h(·) like z

j

= h(a

j

). Then we get for K

unit outputs the following

a

k

=

M

∑

j=1

w

(2)

k j

z

j

+ w

(0)

k0

(2)

These then finally get fed into the last activation

function y

k

y

k

= f (a

k

) (3)

In DL, this multi-layer ANN is made more dense

with several hidden layers in between.

We have some evidence that when AI is menti-

oned, the speaker really means DL. One indicator

of this behavior is to see how data science training

groups are using both terms. For example in Coursera

doing a cursory search on the phrase AI in its courses

will not give results of courses with AI as a title of the

course. Instead, what one gets back are several cour-

ses on DL and machine learning(ML)! This is telling.

Only one of these has the word AI in it and it is IBM’s

”Applied AI with DL”. This shows that the term AI is

made synonymous with DL. Somewhere in the course

description of ML or DL subjects there is a mention

of AI making the description do the following impli-

cation:

deep learning ⇒ arti f icial intelligence

This is the reason why we believe those DL and

ML courses come up.

The result is almost the same in edX but even bet-

ter. In edX, the search came back with 6 courses ha-

ving the title artificial intelligence in them with two

from Columbia University and four from Microsoft.

The interesting part is that along with these, the se-

arch came back with courses having titles containing

data science, ML, DL, data analytics and natural lan-

guage processing to name a few. Here we see strong

support for the idea that when artificial intelligence is

mentioned, DL (and ANN) is the associated concept.

But, this just part of AI, not the whole of AI?

5.2 Why It Is the Driver

We noted that both symbolic and connectionists AI

scientists (in which ANN and by extension DL be-

long), experienced the same earlier funding failure.

Both groups experienced the coldness of the AI win-

ter. So how did ANN with DL come back into the IT

industry?

• Some people kept the faith in ANN. The most no-

table of this is Prof Geoffrey Hinton, who is a part

of the so called San Diego circle (Skansi, 2018).

It was in 2012 when ANN and DL scored good

publicity. Hinton’s team lead by Alex Krizhevsky

out performed the classical approaches to compu-

ter vision winning the competition on ImageNet

(Chollet and Allaire, 2018). This attracted the at-

tention of researchers and industry proponents so

now in data science competitions it is impossible

not to see an entry which did not use techniques

found in dense ANN.

• It is agile. You do not have to worry about whet-

her a feature is relevant or not, though it is a good

practice to do so. However, this administrative

burden prior to doing the computerized execu-

tion of the learning process is alleviated by DL.

Picking the right feature to participate in the ML

process is not a big issue with DL, instead the ana-

lyst spends time tweaking parameters in the ANN

rather than laboring on finding sleek features to

use.

• Computers now are faster. During the first down

trend in AI, the computers were at its processing

limits with the kind of lengthy computation re-

quired to adjust those neural weights continually

to reach its optimum level. Today even an ordi-

nary desktop computer can perform computer vi-

sion analysis using DL specially with the aid of

Graphical Processing Units.

5.3 DL Works, but Why?

Mathematically speaking, no one knows yet why DL

works so well. People use DL heuristically and not

because one has a clear understanding how and why

its mathematics works (Lin et al., 2017). AI scientists

which include obviously researchers from various

mathematical backgrounds are still abstracting from

experience with their proposed foundational mathe-

matics to the AI community. An example is that of

(Caterini and Chang, 2018).

Let’s accept it, all the disciplines be it from bu-

siness, natural, medical or social sciences are in the

quest for that elusive holy grail, the f in y = f (x).

We are always in search to find such a function for

in succeeding, human life’s difficulties might be mi-

nimized if not eliminated. DL and ANN comes close

to approximating this f .

We may generalize DL formally in the following

manner (Caterini and Chang, 2018). Assume we have

L layers in a DL. Let X

i

be inputs coming to neurons

at layer i, and let W

i

be the weights at layer i. We

IJCCI 2018 - 10th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence

148

will express the whole DL as a composition of functi-

onal transformations f

i

: X

i

×W

i

−→ X

i+1

, where we

understand that X

i

,W

i

, X

i+1

are inner product spaces

∀i ∈ L. Further let x be a vector and x ∈ X

1

. Then we

can express the output function produced by the DL

as

b

F : X

1

× (W

1

×W

2

× ··· ×W

L

) −→ X

L+1

(4)

We purposely use the ’hat’ notation to emphasize the

fact that it is estimating the real F behind the pheno-

menon we are modeling.

If we understand further that f

i

as a function de-

pending also on w

i

∈ W

i

then we can understand

b

F

as

b

F(x;w) = ( f

L

◦ f

L−1

··· ◦ f

1

)(x) (5)

We come now to a very important result (Lewis,

2017).

Theorem 1 (Hornik’s Theorem.). Let F be a conti-

nuous function on a bounded subset of n-dimensional

space. Let ε be a fixed tolerance error. Then there

exists a two-layer neural network

b

F with a finite num-

ber of hidden units that approximate F arbitrarily

well. Namely, for all x in the domain of F, we have

|F(x)−

b

F(x;w)| < ε. (Hornik, 1991).

This is a powerful theorem, it states that a.) the

generic DL depicted by

b

F is a Universal Approxima-

tor in that it can estimate real close to the unknown

F; but also b.) that such an F can be approximated by

a single hidden layer ANN. We can set this ε as small

as we like and still find the

b

F(x;w) for this F(x).

DLs are highly effective estimators, it is the first

”goto” method of choice when doing ML. Only when

it fails to adequately account for the dataset under

consideration will the analyst use other techniques.

Experts are of the opinion that using dense ANNs

ie, DL, produce heaps better practical performance re-

sults. However, from a logical or conceptual stand-

point, a simple ANN will do. However, DL, histori-

cally, is a re-branding of the work of Hinton on neural

networks, who even shied away from using the term

for describing his doctoral research (Skansi, 2018).

6 THE AGENT AND ONTOLOGY

VIEW

An agent is a program that acts on behalf of the user

but it can act also on behalf of a system as well. They

can be autonomous or work with others. They sense

their environment and act on it on behalf of an entity

they represent. Lay people are not aware of this AI

view in academia and industry. This is another as-

pect that does not get media attention. AI researchers

adopted the idea that building an AI system is about

the creation of rational agents (Russel and Norwig,

2010) (Russell, 2016) as far back in 1990s.

Under this view something has AI if it can do

bounded optimality, i.e.,”the capacity to generate

maximally successful behavior given the available

information and computational resources” (Russell,

2016). Thus, it has AI if it will choose the best course

of action under the circumstance. The operative word

is action. Under this view an AI that acts by answe-

ring questions is ”passive” if it performs no actions

no more like a calculator. If the focus is in prediction,

commonly found today, but no automatic action ari-

sing from it, then it falls short of AI. By this view,

the product is operating as a ”consultant” and is just a

special case of the high level action oriented function

performed by an agent. We are not saying there are

no recommendation systems out there which may be

viewed as an action, however, this is not happening

pervasively in the community, by the way AI term is

used.

Formally, an agent g turns or maps a series of ob-

servations O

∗

to a set of actions A.

g : O

∗

−→ A (6)

Viewed AI this way then it is easy to assess whet-

her or not a so called entity is doing AI by simply

examining if the said entity transforms what it senses

into behavioral actions (Russel and Norwig, 2010).

The main proponent of this view is Stuart Russell

(University of California, Berkeley) and Peter Norvig

(Director of Research, Google Inc.) Their textbook

Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (Russel

and Norwig, 2010) adopts such a view. The textbook

is found in universities in 110 countries and is the

22nd most cited book in Citeseer

6

. In all likelihood

a computer science graduate would have come across

this view of AI.

Lastly, associated with the above view is another

strict view that says there is no AI without an Infor-

mation Architecture (IA) also known as an ontology

or KR (Earley, 2016). Simply put, an ontology stores

knowledge of a domain of interest which forms the

foundation of computer reasoning wherein agents can

interrogate and formulate the next action to choose.

This view believes it will be hard for agents to run

autonomously if it has no reasoning capability so that

it can react rationally against its ever changing live

environment.

We raise these angles here because they have great

following in the AI community but the popular media

does not cover.

6

http://aima.cs.berkeley.edu/

Making AI Great Again: Keeping the AI Spring

149

7 LESSON FROM ECONOMICS

In a way the resurgence of AI has been driven by its

contemporary use in the enterprise application market

whereby computer software is implemented to satisfy

the needs of the organization. Much of this software

relies on the market’s understanding of DL. Which,

in turn, raises concerns as to where it is in the current

phase of Gartner’s hype cycle.

In order to address this concern, the relationship

of DL with that of AI can be expressed in terms of the

economic model of supply and demand. In terms of

this model, DL through its real world usage for pre-

diction and refinement in practice can be seen as the

outcome of technology production, or supply. Whe-

reas, the demand for DL stems from the use of AI in

enterprise applications. The intersection between AI

and DL is the equilibrium price between supply and

demand and can be interpreted as the relative value

ascribed to AI by enterprises.

This is where the distinction between strong and

weak AI becomes fundamental to understanding the

current phase of Gartner’s hype cycle and whether

another AI winter is likely to arise. DL by all accounts

is, in fact, weak AI as it is geared to solve specific or

particular tasks, namely prediction. However, AI, in

its true sense, is expected to be hard AI as it maintains

a capacity of intelligence to solve any problem. Thus

the relationship between supply and demand can be

updated to be the relationship between the supply of

weak AI with the demand of hard AI.

This distinction matters as the predominant AI

technique applied in enterprise applications is DL.

Like all forms of technology in business, DL will suf-

fer from diminishing marginal returns. This implies

that as more and more DL is applied the lower there

usefulness in fulfilling the needs of the enterprise ap-

plication market.

Without the development of hard AI, as some

point the usefulness of soft AI will reach its limita-

tion and, in turn, be supplied in excess relative to its

demands. This will create a surplus of soft AI. To re-

turn to a point of equilibrium a downward correction

of the value of AI will occur, thereby triggering a new

AI winter. In this basis DL cannot be allowed to be

the only form of AI.

8 KEEPING AI IN SPRING

The McKinsey Company (Chui et al., 2018) is pre-

dicting a very rosy future for AI estimating that AI’s

impact specially in marketing, sales, supply-chain

and manufacturing to be from $T 3.5-15.4. This is

massive. However, could such prophecy produce

another backlash Lighthill Report (Lighthill, 1973)?

At the time of this writing, bloggers are coming out

predicting yet a coming winter (Piekniewski, 2018).

We suggest the following:

1. The late John McCarthy, responding to the Ligh-

thill report said ”it would be a great relief to the

rest of the workers in AI if the inventors of new

general formalisms would express their hopes in a

more guarded form than has sometimes been the

case” (McCarthy, 2000). It is indeed a very wise

counsel.

2. Let us not transfer the achievements of weak AI

into strong AI. It seems when weak AI succeeds,

the enthusiasts are quick the extrapolate this to the

immediate possibility AGI. Part of this is to edu-

cate the media on such distinctions. It is not pro-

ductive to go along their sensational spin without

saying anything.

3. ML and DL practitioners should be aware of the

agent and ontology aspects of AI that way they do

not get carried away with misguided enthusiasm

of the media. Mere classification or prediction is

only small aspect of an agent’s function; the AI

device of any sort must act beyond ”consultant

answering” activities.

4. Though DL has had lots of gains, it has limitations

too. DL is not enough in most cases because pre-

diction does not address subsequent needed acti-

ons after that. Next best action to take involves

reasoning beyond what DL provides. Many be-

lieve the step forward is to combine symbolic AI

with connectionist AI (Sun and Alexandre, 1997).

We also concur with (Marcus, 2018) which says

that DL is not adequate to produce higher level of

intelligence. We believe that the best way to do

this is embedding DL into some form of an agent.

By economic reasoning, DL will not be the sole

source of AI success. This is not sustainable in

the long run.

5. Overselling AI through, i.e., weak(soft) AI, will

imply overloaded demands spilling over to pres-

sure for a strong (hard) AI. A balanced message is

to communicate that we are not there yet thereby

adjusting the expectation of investors. This has a

better effect of being in the realm of the sustaina-

ble. Promising modest jumps in AI ability then

exceeding it is a far suitable outcome than raising

the promised bar and then failing to clear it. The

latter brings disrepute and makes us worst off.

IJCCI 2018 - 10th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence

150

9 CONCLUSION

In this work we examined the phenomenal increase

in interest on all things AI. We wanted to go beyond

the steam and smoke with the hope of finding ways to

sustain this positive and hopeful enthusiasm in AI.

To do this, we took the view that we have to study

its past. We studied the origin of the term and its taxo-

nomic subclassifications. We tracked its rise and then

its fall and then its rise and fall again noting that the

one holding up the flag for AI is DL. We explained

what makes DL the silver bullet tool and how holds

the beacon for AI. We showed its mathematical form

and stated how it is a universal approximator. We took

some insights from economics as well, predicting that

if there is no current slowing down of over AI use as a

term, the gains will break. We avoided incredulity by

mentioning that the agent view of AI makes DL only a

small aspect of computational intelligence in that the

next phase is to embed it into an agent system. We

can see that the result of DL work becoming input to

data kept in ontologies.

Lastly, we did not finish without providing a sug-

gested path way to keep AI in its peak hoping this

present benefit goes for a very long time. Our hope is

that this promotes integrally honest conversation with

our peers.

REFERENCES

Ahvenainen, J. (2015). Artificial Intelligence Makes

a Comeback. https://disruptiveviews.com/artificial-

intelligence-makes-a-comeback/.

Aube, T. (2017). AI and the End of Truth The Star-

tup Medium. https://medium.com/swlh/ai-and-the-

end-of-truth-9a42675de18.

Bishop, C. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Lear-

ning. Springer.

Buchanan, B. G. (2006). A (Very) Brief History of Artificial

Intelligence. AI Magazine Magazine, 26.

Caterini, A. L. and Chang, D. E. (2018). Deep Neural Net-

works in a Mathematical Framework. Springer.

Chollet, F. and Allaire, J. (2018). Deep Learning with R.

Manning Publications.

Chui, M., Manyika, J., Miremadi, M., Henke, N., Chung,

R., Nel, P., and Malhotra, S. (2018). Notes From The

AI Frontier: Insights From Hundreds of Use Cases.

McKinsey Global Institute.

Datta, S. (2017). The Elusive Quest for Intelli-

gence in Artificial Intelligence. http://hdl.handle.net/

1721.1/108000.

Earley, S. (2016). No AI without IA. IEEE IT Professional,

18.

Flasinski, M. (2016). Introduction to Artificial Intelligence.

Springer.

Haykin, S. (2008). Neural Networks and Learning Machi-

nes, 3/e. Pearson.

Hornik, K. (1991). Approximation Capabilities of Mul-

tilayer Feedforward Networks. Neural Networks,

4:251–257.

Lee, N. (2017). AlphaGo’s China Showdown: Why it is

time to embrace Artificial Intelligence. Sothern China

Morning Poast - This Week In Asia.

Lewis, N. D. (2017). Neural Networks for Time Series Fo-

recasting in R. N. D. Lewis.

Lighthill, J. (1973). Artificial Intelligence: A General Sur-

vey.

Lin, H., Tegmark, M., and Rolnick, D. (2017). Why Does

Deep and Cheap Learning Work So Well? Journal of

Statistical Physics, 168.

Marcus, G. (2018). Deep learning: A critical appraisal.

arXiv:1801.00631.

McCarthy, J. (2000). Review of Artificial Intelligence: A

General Survey.

McCulloch, W. and Pitts, W. (1943). A Logical Calculus

of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity. Bulletin of

Mathematical Biophysics, pages 115–133.

Piekniewski, F. (2018). AI Winter Is Well On Its

Way. https://blog.piekniewski.info/2018/05/28/ai-

winter-is-well-on-its-way/.

Russel, S. and Norwig, P. (2010). Artificial Intelligence: A

Modern Approach, 3rd Ed. Prentice Hall.

Russell, S. (2016). Rationality and Intelligence: A Brief

Update. In Muller, V. C., editor, Fundamental Issues

of Artificial Intelligence. Springer.

Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, Brains, and Programs. Behavi-

oral and Brain Sciences, 3:417–424.

Skansi, S. (2018). Introduction to Deep Learning. Springer

International Publishing AG.

Smolensky, P. (1987). Connectionist AI, Symbolic AI, and

the Brain. Artrificial Intelligence Review, 1:95–109.

Sun, R. and Alexandre, F. (1997). Connectionist-Symbolic

Integration: From Unified to Hybrid Approaches. L.

Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Making AI Great Again: Keeping the AI Spring

151