Tool for Enhancing Family Communication

through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection

Naoya Tojo, Hiromi Ishizaki, Yuki Nagai and Sumaru Niida

KDDI Research, Inc., 2-1-15 Ohara, Fujimino, Saitama, Japan

Keywords:

Families, Family Communication, Experience Sharing, Planning, Retrospection, User Study.

Abstract:

Advances in mobile communication technology have eased time and space constraints in communication bet-

ween individuals. Although communication support tools are efficient in non-frequent and transitory relations,

they are not necessarily a breakthrough for communication among people such as families in which face-to-

face communication serves a crucial role. To enhance family communication, we advanced a project to develop

the tool in a phased manner. First, we conducted an ethnographic study to understand users and extracted in-

sights related to family communication. The results of the ethnographic study revealed that a family who was

maintaining good communication planned, experienced, and retrospected family events together. Based on

these insights, we created the concept of a tool that combines features of a shared calendar and a photograph

album. We iteratively prototyped and tested prototypes so as to increase user acceptability by improving user

interfaces. Through user tests, the prototypes demonstrated that a parent and child could cooperate to plan

family events reflecting their intentions and preserve past family experiences.

1 INTRODUCTION

Advances in information and communication tech no-

logy (ICT) have led to the widespread use of vari-

ous to ols supporting communication between indivi-

duals. As these tools h ave been distributed to mo-

bile devices, time and space constraints in c ommuni-

cation have been greatly eased. Although the com-

munication support tools are efficient in maintaining

weak ties (Granovetter, 1973) such as non -frequent

and transitory relations, they are not necessarily a

breakthrough for communication among people with

strong ties such as families. The use of ICT devices

has various practical usefulness; however, it also has

a negative aspect on the strong ties in which face-to-

face com munication serves a crucial role. For exam-

ple, there is the further isola tion of individuals an d the

lack of empathic abilities due to a shift of conscious-

ness from face-to-face communication to mobiles. It

is necessary to design a tool to emphasize an aspect

of I CT underpinning of family communication.

A variety of research projects have addressed the

development of ICT-based tools designed to enhanc e

family communicatio n by sh aring experiences as an

alternative to simple voice communication or messa-

ging (Cao et al., 2010; Crabtree et al., 2004; Heshmat

et al., 2017; Inkpen et al., 2013; Neustaedter et al.,

2009; Oduor et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2017). For the

offline situation in homes, interfaces that mediate fa-

mily commu nication by sharing information such as

daily tasks and family members’ schedules have been

proposed to imp rove the efficiency of home manage-

ment (Brush and Turner, 20 05; Neustaedter and Bern-

heim Brush, 2006; Neustaedter e t al., 2009; Pan et al.,

2015).

In response to concerns that the use of mobiles is

increasing the isolation of people, our project recon-

sidered problems of family communication and de-

signed a tool. We a dvanced the development of the

tool in a phased manner from a user perspective by

referrin g to a design thinking process (Dam and Si-

ang, 2018; Cul´en and Følstad, 2014; Thompson et al.,

2017).

In this paper, we report th e current prototy pes,

and also report the development proc ess and findings

from a user study. First, we conducted a compara-

tive ethnographic stu dy. From observations and inter-

views, we focused on what family members do toget-

her in a problem setting for family communication.

Then, we r eviewed conventional approaches to the

problem in family communic ation and designed the

framework of this research. As a result, we created the

concept of a tool that combin es fea tures of a shared

calendar to manage future and current events and ones

34

Tojo, N., Ishizaki, H., Nagai, Y. and Niida, S.

Tool for Enhancing Family Communication through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection.

DOI: 10.5220/0006896600340044

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2018), pages 34-44

ISBN: 978-989-758-328-5

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

of a photogra ph album to retr ospect past events. To

prove that family communication is complemented by

sharing past expe riences and futur e intentions, we de-

veloped prototypes of th e tool. We iteratively refined

the prototypes on the basis of feedb ack gathere d from

user tests so as to increase user acceptability by im-

proving the user experience (UX).

2 ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY

We co nducted an ethnographic study on four families

in their homes to understand their lives and ways of

communication within a context by utilizing observa-

tions and interviews. We set tow criteria for selectin g

the families. One is whether it is a family whose

children are not preschool. In Japan where we con-

ducted this study, there is a tendency for less commu-

nication with parents as children grow up. The other

is whether father’s involvement in child rearing and

household tasks is high. We estima te d degree of fat-

her’s involvement in household tasks from proportion

of sharing between spo uses. We evaluated degree of

involvement in child rearing based on whether a fat-

her had used company’s support systems (e.g., child-

care leave, sick/injured child nursing leave, reduction

in working ho urs, and telecommuting). We sampled

two families (Family 1 and Family 2) who satisfy a ll

of the criteria and two families (Family 3 and Family

4) who don’t satisfy all of the criteria.

We observed realities of family member’s beha-

vior and communicatio n. After the observation, we

condu c te d a detailed interview including items related

to ways to record and manage family events and daily

life. The ho me visit survey took about three ho urs per

household.

In this section, we compare families whose com-

munication styles are contrasting , and describe the

findings. Family 1 and Family 2 were having diverse

communication means. Family 3 and Family 4 were

feeling a lack of communication between the pa rents

and the children. Then, we identified insights that

enable family c ommunication to be maintained.

2.1 Summary of Findings

2.1.1 Family 1 and Family 2 — Families with

Diverse Communication Means

Family 1 consists of f our members: workin g parents,

a son in high school, and a daughter in junior high

school. Family 1 regarded household tasks as work

to be done together by all members and shared them.

When the family m e mbers did household tasks toget-

her, they not only aimed efficiently to get tasks done

but also were communicating with each other. For

example, when the parents and the child ren did hou-

sehold tasks togeth e r, the mother taught the children

how to cook and clean, and the children also positi-

vely asked how to do.

There were rules such as “Eat dinner together to

the extent possible” and “Everyone at home should

see off a member who leaves home” in orde r to con-

sciously maintain face-to-face communication bet-

ween the members. These rules were made fro m fat-

her’s intentions to maintain opportunities for the fa-

mily members to be considerate to each other. As

an e ffort to complement family communication, they

shared messages and tasks by using a white board, a

calendar, and notes taped to walls, a fridge, and doors.

The materials were visible everywhere in the hou se.

The members conversed about the materia ls as topics.

Moreover, they shared messages and photo s of casual

experiences by means of mobile devices on a daily

basis. Family schedules were shared with the mate-

rials or verbal interactions in advance. They collecti-

vely organized photo s and videotapes of past family

events such as trips, and promoted conversation by re-

trospecting stored memor ie s again. However, because

they have recently taken photo s with digital devices

and have not developed them, the data are dead-sto red

in the devices and not retrospected later.

Family 2 consists of four members: work ing pa -

rents and two preschool sons. The c ouple of Family 2

had the clearest distribution of household tasks com-

pared to the other families. The father answered that

his sharing rate of household tasks was 40-50% of the

total. He also said that both himself and children are

proactive in co mmunicating with each other. Furth e r-

more, he tried to talk with his w ife for more than six-

teen minutes a day since he got information that it

increases feelings of happiness before. With regard

to planning family events such as traveling, the cou-

ple said they enjoyed doing together while thinking

“what they want to do with their family ” rather than

“what o neself wants to do.”

Photos taken in past family events and everyday

life were stored on parents’ mobile phones, respecti-

vely; however not managed any further. The parents

had a hard time fin ding a specific photo that we asked

to show us during the interview. They expre ssed this

state as “a stratum of memories.”

2.1.2 Family 3 and Family 4 — Families Feeling

Lack of Communication

Family 3 consists of four member s: working parents

and two daughters, one in junior high school and one

Tool for Enhancing Family Communication through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection

35

in elementary school. The father was busy with his

job and returned home late on workdays. He was not

able to spend much time with his family because his

holidays were on days other than weeken ds. Th e mo t-

her worked at home twice a we e k on Tuesdays and

Fridays. The younger daughter was busy with a cram

school and five kinds of lessons. Communica tion be-

tween the father and the elder daughter was particu-

larly poor.

Household tasks we re not shared, they were done

only by the mother. The tasks piled up an d reduced

the mother’s scope and time for family communica -

tion. Nevertheless, almost all c ommunica tion was

steered by the mother when we visited. For exam-

ple, she encou raged family members’ voluntary com-

munication during meals by providing conversational

materials. Handouts and notes distributed at schools

were stuck on the fridge door with a magnet, and only

the mother handled th em out and gave directions to

the other family members.

The photos of past family events were not mana-

ged because the parents did n ot know how to trans-

fer the data fr om devices to a PC. They enjoyed ta-

king photos, but found the rest of the procedures trou-

blesome.

Family 4 consists of five m embers: working pa-

rents, a son in elementary school, and two preschool

children. The father was busy as with the father in

Family 3 and went on business trips frequently; the-

refore, the mother was aware of lack of dire ct commu-

nication with his husband. The moth er answered that

she kept more than 90% of household tasks. She was

tied up with present tasks occurring one after anot-

her. When the mother washed dishes after lunch, the

children talked to her to attract mother’s attention; ho-

wever, the mother p rioritized do ing househ old tasks.

More than a thousan d photos were stored in a di-

gital camera of the parents; however, the mother did

not know how to display th em.

2.2 Problem Setting

We defined the pr oblems to tackle on the basis of fin-

dings from a comparative study on family communi-

cation.

Members of Family 1 and Family 2 shar ed domes-

tic routine tasks and individual member s’ schedules in

advance. As described above, the father’s intentions

to maintain ties a mong the family members were also

shared by setting rules that serve as guidelines for the

family. On the other hand, there were no opportuni-

ties to do work together in Family 3 an d Family 4 due

to the busyness of the father and the daughter. Only

the mother handled domestic tasks, cared about other

members’ schedules, a nd encouraged family commu-

nication, particularly in Family 3. Time for maintai-

ning communication among family members has be-

come more limited recently. Parents spend mo st of

their time at work ( Roy and Bh attacharya, 2015), and

some children are busy going to cram schoo ls and ha-

ving extra lessons (Brown et a l., 2011).

Temp orally and spatially synchronized experien-

ces directly lead to enhancement of communication.

In Family 1, daily work such as cookin g and clea-

ning gen erated the family face-to-face communica-

tion. They also sha red individual experiences with

each other by mobiles on a daily basis.

Another mode of experience sharing was a lso ob-

served after a phase of planning and experience. As

observed in Family 1, ac cumulated family experien-

ces (e.g., family trips, ch ild growth record, and school

events) deepens memories, and can later be triggers

for conversation and retrospection. Tools such as so-

cial media (Guy et al., 2016) and online chat (Neus-

taedter et al., 2015) are useful to temporary interacti-

ons among family m e mbers. In order to further en-

hance family communication which is the strong ties,

it is necessary to share not only as well as temporary

communication, but also a whole life cycle of family

events including past and future . The photos of past

family events were previously physically organized

and managed. Family 1 used to create photo albums

for each event. However, nowadays photos are taken

by ICT d evices, m a naged as electronic data, and tend

to be dead-stored on personal devices, a s was the case

in fo ur families.

We obtained the insight that sharing expe riences

are important for enhancing family communication.

In Family 1 and Family, which was maintaining good

communication, the experien c es such as sharing plans

and directions, daily face-to -face communication and

household tasks, and retrosp ection of family events

by photos and videos enhanced satisfaction with fa-

mily communication. By contrast, Family 3 an d Fa-

mily 4 lacked opportunities to communicate in these

ways. Thus, we established the concept of a tool that

promotes family communication focused on what fa-

mily member s do together. It is necessary to design

UXs that comprehensively support family collabora-

tion over plan ning, experience, and r etrospection.

In addition, since communicatio n between a father

and child tend s to be particularly lacking in a family

(Lukoff et al., 2017), we conducted the following user

studies fo cusing on that relations.

CHIRA 2018 - 2nd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

36

3 RELATED WORK

In the field of human-computer interaction (HCI), re-

search on family communication support has received

a lot of attention.

Systems that support opportunities for individuals

to be together and support online experienc e sharing

have been proposed. Systems for realizing shared-

dinners, event remote participation, or remote story

reading have been suggested as challenge s to the dis-

tance gap (Inkpen et al., 2013; Oduor et al., 2 013).

As for the time gap, there is research on communica-

tion taking into account that family members are in

different time zones (Heshma t et al., 2017; Cao et al.,

2010). G2G project (Forghani et al. , 2018) designed

a system that allows grandparents and grandch ildren

over distance to share an awareness of each other’s

lives by means of a shared calend ar and video messa-

ging. These particularly focus on ongoing experience.

In the phase of retrospection, family membe rs re-

trospect records and memories of their past experien-

ces. Although dead storage of photos was a problem

in the case of Family 1 and Family 2, there is rich lite-

rature on photoware, which is technology for storing,

managing, and sharing digital photos in the field of

HCI. Requirements for photoware were discussed re-

garding the difference in usage situation between con-

ventional and digital photos (Frohlich et al., 2002).

Photoware assuming cooperative photo sharing is also

explored for home use (Crabtree et al., 2004) . Pro-

totypes were created to allow users to easily and flex-

ibly share a digital photo collection on mob ile devices

in the face- to-face co ntext (Luc ero et a l., 2011). Su-

venirs project (Nunes et al., 20 08) proposed a photo-

sharing approach that displays digital photos with a

link to a p hysical memorabilia as affordances to in-

crease opportunities of sharing in physical space.

Tools for improving the efficiency of household

tasks by utilizing ICT have been propo sed. Especially

in homes, visual approaches based on the advantage

of a calendar is effective for mana ging schedules and

recording experiences. Families use paper calendars

as a tool to help stay organized; they are easy to use,

share, move, personalize, and create an instant archive

of family activities (Brush and Turner, 2005). Pre-

vious work has shown that dig italize d c alendars a nd

other messageboard-like interfaces are useful for fa-

milies to address co operative work (Neustaedter and

Bernheim Brush, 2006; Neustaedter et al., 2009) and

to handle daily tasks and incoming information ( Pan

et al., 20 15). MyCalendar (Abdullah and Brereton,

2015; Wilson et al., 2017), whic h is a calendar tool

with photos and videos a s contents, helps childr en to

show what is happening both at home and sch ool to

teachers and parents and to communicate about their

motivations and interests, even if the children have

limited verb a l skills. These functions support the ma-

nagement of domestic routine tasks and temporary in-

teractions or ena ble the family to retrospect the expe-

rience itself later. Families can spend together more

time by improving the efficiency of tasks in the home.

In this resear c h, in addition to the experience and

the retro spection of the family collaboration, we also

consider the “planning ” phase preceding the other

two phases. We broadened the sco pe of collaborative

work within families to sharing intentions and plan-

ning.

4 DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

In this resear c h, we firstly ideated solution. Then we

iteratively created prototypes and tested them accor-

dingly. The tests are another chance to understand

users from their feedback on the created pr ototypes.

We ad opted a formative evaluation approach (Mag-

uire, 2001) to develop prototypes. Each cycle com-

prises empathy for users, defining challenges to take

on, and ideation .

4.1 Ideation

From the resu lts of the ethnographic study, we ide-

ate functions for a family to plan a nd share family in-

tentions, manage family events and embed them, a nd

preserve past family experiences to be retrospected to-

gether. We extracted the features of family communi-

cation obtained from the results of the ethnographic

study. We refined ideas of a tool while summarizing

the features through brainstorming by project mem-

bers. We repeatedly evaluated the ideas as compare d

with the results of the ethnographic study.

After we carried out ideation only within the pro-

ject member, the development projec t invited an ar-

tist

1

to join ideation process, and d iscussed the featu-

res of the communication supp ort tool. An example of

her work is “collage of time

2

” glued to a large calen-

dar that is painted on canvas of 1 620×1303 mm and

its concept can suit in intent of the tool. It is an assem-

blage of different materials accumulated in daily life,

for example, photos, illustrations, notes, article clip-

pings, movie or concert tickets, railway tickets, QR

codes with embedded secrets. She used the work as

a calendar fo r schedule management and also used as

an album to be retrospected later by adding contents

1

http://rieko.jp/

2

http://renga.com/riekoarc/100LoXXPW[/

Tool for Enhancing Family Communication through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection

37

to past days. The inspiration of her previous work

triggered the id e a for a tool with which future plans

and past exper ie nces of family events can be managed

in time-series relation to each other by using contents

such as photos, pictures, an d texts.

4.2 Prototype 1

4.2.1 User Study with a Paper Prototype

We tested a simple p a per prototypin g to clarify the

minimum functions necessary to edit materials. Paper

prototy ping in the early stage of development has the

advantages of r educing the risk of rewor king in agile

development and sharing common perceptio ns about

products among project members. A Japanese pair of

a father and his six-year-old child addressed prototy-

ping together fo r six months as an experimental test.

During the period, they expressed their intentions for

event planning and memories of past events on the

calendar by cutting and pasting the photos taken at

events, writing, and drawing.

After the test, the father shared r e sulting calendars

and informed free opinions and characteristic beha-

vior to the other project members. We documented

feedback from the father and listed activities seemed

to be effective for family communication.

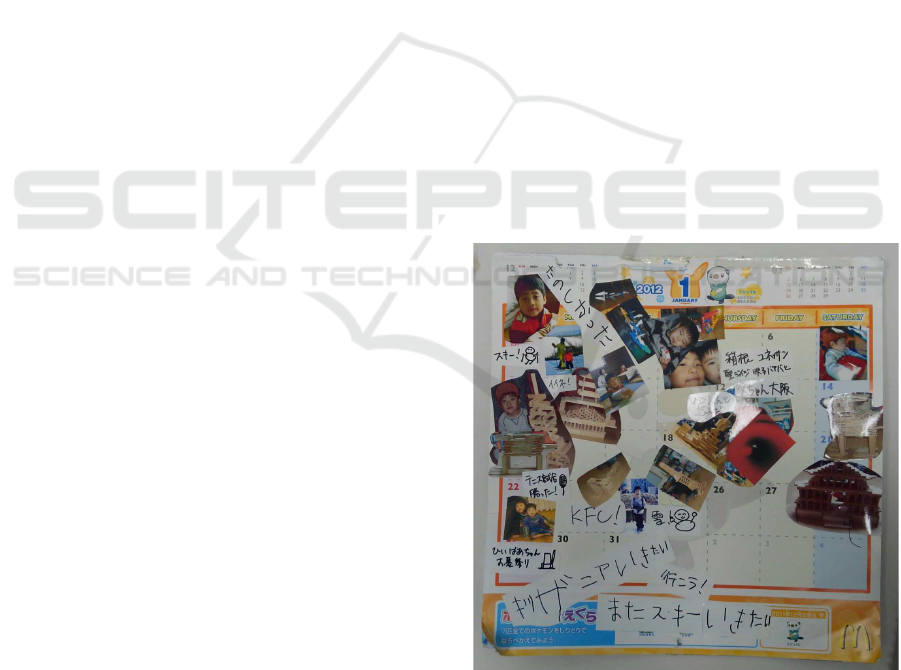

Figure 1 shows the resulting family calendar.

There was interaction in the phase of planning be-

tween the father and child on the prototype. The

child’s responses about past events are shown as the

texts of “It was fun,” and “I want to go skiing again.”

In terms of hopes for a future plan, we could see that

the child wanted to go to KidZania, which is a child-

friendly family ente rtainment center. The father rep-

lied, “Nice!” and “Let’s go,” to the child’s remarks.

Since continuous use by the fathe r and child was

confirmed over the test period of six months, we pre-

sumed tha t the development was worth moving on to

the next process.

4.2.2 Requirements for Editing Function

The user’s feedback revealed that there was demand

for a function to rotate and zoom in and out of the

photos in order to give significance to each content

accordin g to its position and size. Th e resulting pro-

totype, w hich was created by editing not only photos

but also texts and pictures, indicated the need for va-

rious ways of inputtin g. Besides, a function to rear-

range the contents was proposed due to difficulty in

changin g the content layout o nce glued on the pap e r.

4.3 Prototype 2

We developed a calendar app taking the results on the

paper prototypin g into account, and implemented it

on the Apple iPad Air. It was used by two families

for one mo nth. Through the user tests, the operation

of each implemented function and the influence of use

on family communication were confirmed. Moreover,

we identified problems in UX of the second prototype.

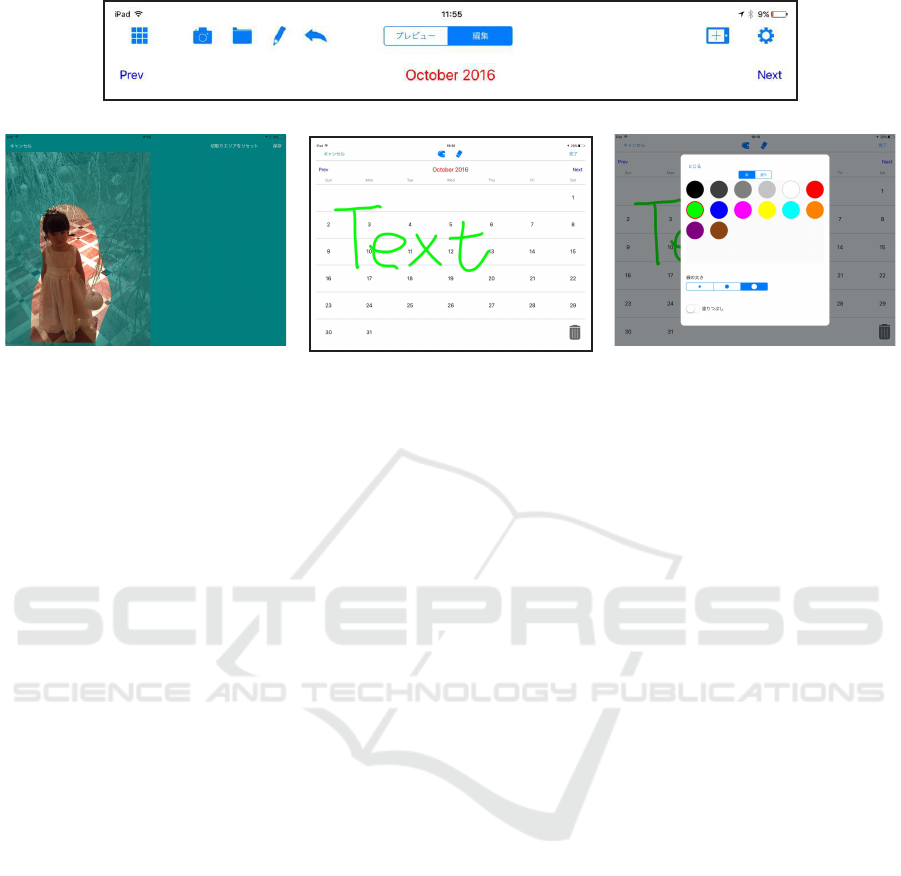

In this subsection, firstly, basic ope rations and im-

plemented functions were outlined with explanation

screens shown in Figure 2. Secondly, problems and

insights are formed for id e ation to create solutions re-

quired f or a third deliverable .

4.3.1 Screen User Interface Design

Figure 2 (a) shows the basic screen of the seco nd pro-

totype of the calendar app. By tapping the grid square

icon in the upper left corner of the scree n, all created

contents are listed. The camera icon and folde r icon

are used to invoke photo import functions. The pencil

icon is for handwriting functions. The left arrow icon

is used to undo the last action. T he preview mode

and edit mode switch by selecting either tabbed do-

cument interface (tab) in the top middle of the screen.

The gear ic on is used to confirm and change the set-

tings. By tappin g the icon to the left of the gear icon,

Figure 1: A paper prototype created by the father and child.

The Japanese texts in the prototype mean the following (in

order from the upper left). “It was fun.” “Skiing!” “Nice!”

“Hakone Yunessun with Ken Grandpa and Eiko Grandma.”

“Father is at Osaka.” “I played with Hikari.” “I won a

game of tennis.” “KFC!” “Snow.” “Visiting great grand-

mother’s grave.” “I want to go to KidZania.” “Let’s go.”

“I want to go skiing again.”

CHIRA 2018 - 2nd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

38

(a) The graphical control elements on the top of the basic screen.

(b) The photo cropping function. (c) The sample of drawing. (d) The digital palette.

Figure 2: The user interface of the second prototype.

a screenshot is captured and exported in the Photos

app, which is the default app of the iOS. The month

displayed in the calendar changes by tapping “Prev”

or “Next.”

4.3.2 Functions for Importing and Processing

Picture Contents

There are two ways to import photos to the app. One

is to cooperate with the iPad default Photos ap p. This

function is invoked by tapping the fo lder icon. Pho-

tos taken in the past and stored in the Photos app are

available in this way. The other is invoked by the ca-

mera icon and the way to take photos by launching

the Camer a app.

After selecting or taking a photo, the proce ss fir-

stly shifts to the photo cropping fu nction by which a

user can cut ou t a photo in free form. A desired area

of the photo is left as content by tracing the ou tline of

the area to be c lipped with the finger as shown in Fi-

gure 2 (b). Until the croppin g area has been determi-

ned, the user can cancel editing or reset the cropping

area. Once the oper ation ha s been completed and the

cropping area has been determined, its area cannot be

modified later. The cropped content c an be zoomed

(by pinching in or out the content) and rotated (b y

multi-touching and rotating without pinching), and its

position on the calendar can be moved (by dragging).

The size, the rotation, and the po sition can be modi-

fied later.

4.3.3 Handwriting Functions

The handwriting functions are invoked by tapping the

pencil icon (see Figure 2 (a)). Figure 2 (c) shows

a sample of the handwriting conte nt in the handwri-

ting screen. By tapp ing the palette icon at the top of

the h andwriting screen, the user can choose the pencil

tool from three widths and 14 colors in Figure 2 (d).

The eraser icon is used to erase handwritten content.

By tapping “Done (in Japanese),” editing of the hand-

writing content is comple ted. The user can zoom, ro-

tate, and move the handwritten contents in the same

way as the photo contents.

4.3.4 Test Conditions

We lent an iPad Air with a calendar app to two Japa-

nese families (Family 5 and Family 6) and conducted

the user test on them for a month. The two fami-

lies are different from the families in the ethnographic

study. Family 5 consists of a father in h is forties and

his family including his three sons. Family 6 consists

of a father in his forties and his family including his

two daughters. The method of using the app and the

purpose of enhancing the family communication were

explained before conduc ting the user study. The sub-

jects were asked to ca pture the screenshots at the end

of the day if they used the app in the day in order to

log the transition .

After the families u sed the a pp for one m onth,

semi-structured interviews were conducted for about

one hour on the fathers of Family 5 and Family 6,

respectively. Interview items included usages such

as f requency and situations, change in father-children

communication, and feeling of use of each function.

The scre enshots captured by subje cts through the test

period were reviewed during the interview. We taped

the interviews.

Tool for Enhancing Family Communication through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection

39

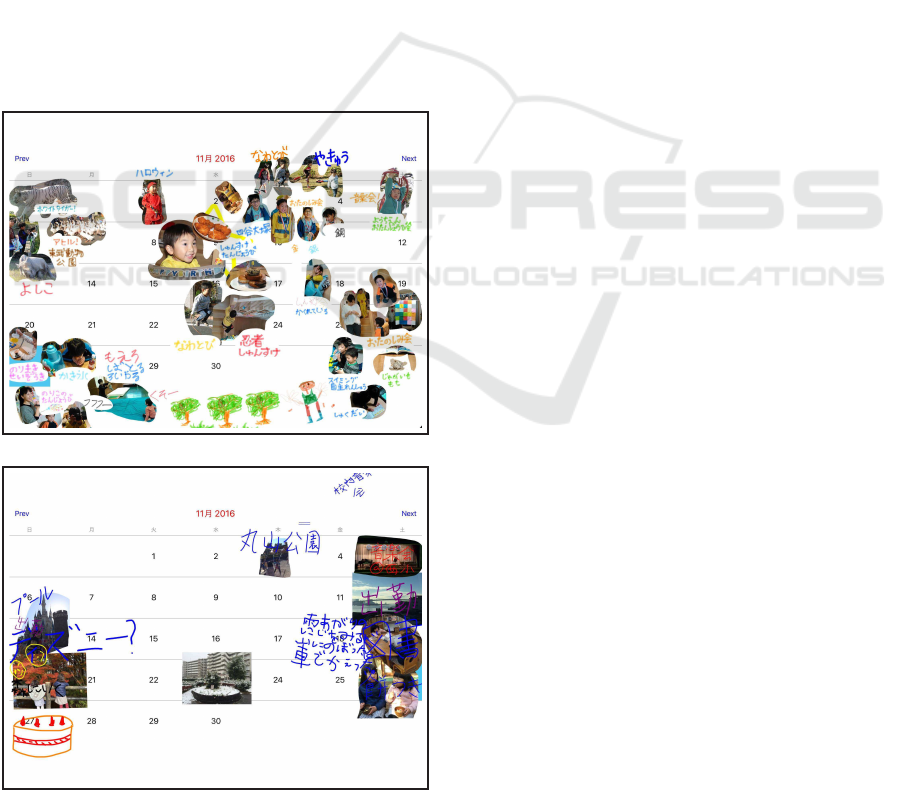

4.3.5 An Overview of the Resulting Calendars

Figure 3 shows the final calendars create d by eac h

family. Family 5 and Family 6 used photos of past

family events, daily meals, and childr en as contents.

The handwriting function was used to create a brief

explanation of some photo contents. Family 6 used

the handwriting function to draw a picture of a cake.

In the case of Family 6, the app was also used to ma-

nage fu ture events such as father’s working o n a day

off and a pla c e wher e a child wanted to go on holiday.

During the 30-da y test period, Family 5 and 6 took

screenshots (that is, they used the app ) seven and 15

times, respectively.

4.3.6 Requirements for Functional Improvement

In the interview, comments related to the usability and

functions of the app were fed back from the users.

We extracted r e marks, prioritized them, and decided

three requirements for func tional improvement to be

addressed when development of a next p rototype. The

requirements are the following. A keyboard interface

(a) Family 5.

(b) Family 6.

Figure 3: Calendars for a month created by two families.

was demand ed as well as a handwriting fun c tion so as

to input chara cters efficiently. When a number of con-

tents are made and cover the calendar, the date indica-

tion cann ot be seen. Because commonly there are few

family events on weekdays and many on holidays, the

widths of date bo xes in the calendar need to be chan-

ged a ccording ly.

4.3.7 Insights from General Comments

A father comm ented that he selected the photos to

create contents and gathered useful infor mation regar-

ding f uture family events by utilizing a mobile in his

spare time such as time spent commuting. Then, he

integrated them into the calendar tool. It is possible

to use photos taken in various pla ces with mobiles.

As overall impressions of creation of the calendars

by using the second prototype, we obtained the com-

ments below: “It was interesting to start creating the

calendars. Especially by cropping the photos, I felt it

put on a good show when it was pasted. We did not

use the app for the purpose of schedule management,”

and “It was interesting to change the photo size to

larger or smaller freely because the size expressed my

thinking at that time.” The secon d comment stands f or

our intention to use fu nctions to edit contents. As for

the feeling of accomplishm e nt by planning interacti-

vely, there was one comment “I felt like ‘We’ decided

the schedule by talking about and writing plans cle-

arly with children.” Moreover, there was the insight

that if there are many blanks on a cale ndar when the

users lo ok back at a past month, it motivates them to

plan more events in the following months. From the

above, it is suggested that the scope of cooperation

extends to the planning phase.

4.4 Prototype 3

In th is subsection, we outline additional functions for

the second prototype and report the results of a works-

hop that we conducted as a test of the third pr ototype.

4.4.1 Added Functions

Figure 4 shows the basic screen o f the third prototype.

The box of the current date is indicated in light blue.

We implemented the keyboard input function to

improve the usability o f character input. The size, co-

lor, and font design of ch a racters can be chang ed. Si-

milarly to other contents created by using the photo

edit function or the handwriting function, th e texts

created b y the keyboard function can be zoomed, ro-

tated, and moved, however they cannot be re-edited.

By tapping the magnifying g la ss icon in the pre-

view mode shown in Figure 4 (a), character strings

CHIRA 2018 - 2nd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

40

previously inputted by using the keyboard functio n

can be searched. Wh e n multiple sear c h resu lts are hit,

the user interface for selecting a resu lt is displayed ,

and the calendar turns to the month that includes the

selected text conte nt. When there are n o correspon -

ding search results, a message informing to that effect

is display ed in a dialog box. This search function in-

creases accessibility to past contents.

A function to select the display format of the

calendar was implemented. By tapping an ic on to

the right o f the preview/edit mode switching tab, the

widths of date boxes in the calend ar change . The user

can choose the display forma t from th e pattern that the

size of all date boxes is the same and the pattern that

the date boxes of Saturday and Sunday are wider than

the other boxes. By switching the tab, the user can

choose whether to display at the forefront calendar

dates or created contents. If the calendars are covered

with a number of contents, the date indication can be

seen by displaying the calendar date in the forefront

(a) Preview mode.

(b) Edit mode.

Figure 4: A basic screen user interface of the third pro-

totype. The calendar part of both modes is the same. The

control elements on the top of the screen are different.

owing to this function.

Moreover, by tapping an arb itrary date box, its co-

lor turns gray and the contents created or edited on the

day are listed. By tapping arbitrary content on the ca-

lendar, contents taken on the same day as the content

taken are listed. These content-date linkage functions

increase accessibility to past family experiences in re-

trospection.

4.4.2 A Workshop with the 3rd Prototype

We held a workshop to observe the usage situation

and to collect impressions. When we tested the paper

prototy pe and the second prototype, we mainly eva-

luated the finally cre ated calendars. In the workshop

using the third prototype, we observed the process by

which the father and child created contents together.

The participants were fou r Japanese pairs o f a father

and a child younger than elementary school age. We

asked the participants to bring data of photos taken in

the past to the workshop. The data were respectively

imported to the four iPad Airs in which the developed

third prototype was implemented.

After the introduction, a project member explai-

ned how to use the app and demonstrated the creation

of the contents for about fifteen minutes. Next, the

participants freely created the contents on the calen-

dar for about o ne hour. Finally, we gathered users

feedback on their impressions of the creation process,

usability, and their intention to use it continuously.

During the workshop, when the participants showed

characteristic behaviors, we took notes as event data.

Voice data of each p air we re recorded respectively.

We analyzed users fee dback and ch aracteristic beha-

viors by using the voice data.

As a result, the participants placed contents cre-

ated from pho tos taken in the past on the dates the

photos were taken. Many of the contents created by

cropping photos of past events had an added hand-

written explanation, as with Figure 3 (a).

Regarding forward plans, the father and child tal-

ked about and decided what they wanted to do. Con-

tents representing intentions such as family trips and

going to re staurants were created in the future calen-

dars. Images from the Internet and handw riting con-

tents were used to create the contents related to the

future plans as shown in Figure 5 (a). One pair used

content created by clipping a photo of the daughter

ballet dancing as an icon representing a weekly lesson

schedule. Although the fathers utilized the keyboar d

input function, the childr en did not utilize it muc h be-

cause they cou ld not read and write yet. Meanwhile,

one ch ild utilized the keyboard input function to cre-

ate decorating contents with Emoji as shown in Fi-

gure 5 (b).

Tool for Enhancing Family Communication through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection

41

4.5 Discussion

Participants planned family events and embedded

their past experiences together. Thr ough observation

of actual work process, we found that the fathers fir-

stly let their child edit th e calendar in the child’s own

way and then supported them. Fathers who partici-

pated in the workshop commented that they would

like to see the calendars individually created by ot-

her family members although it is good to create the

calendars togethe r. From th ese insights, we assumed

that fathers want to know the feelings and thoughts

of children and other family members and the calen-

dar tool is helpful for realizing this. Ther e was one

comment related to communication in the planning

phase, that is, the father could understand what the

child wants by using the prototyp e and determining

their intentions together with his child. The father

found that there was not much to talk about w ith the

child about plans previously.

One father took abou t one hundred photos a

month. On the othe r hand, the other three fathers

did not take photos often an d many of the photos th a t

they brought to the workshop were taken by mothers.

Although two fathers indicated their intentions to use

the tools continuously, the other two fathers could not

decide by themselves because whether to allow their

children to use the tablets were dependent on the mo t-

hers’ decisions. We recognize that it is ne cessary to

consider the mother as an important role in stakehol-

der analyses.

(a) Future intentions expressed by images from the

Internet. Japanese text written in red lines means “I want

to go early.”

(b) Emojis inputted from the keyboard function.

Figure 5: Examples of contents created in the workshop.

5 CONCLUSIONS

For enhancing family communication, we advanced

the development of the tool in stages. First, we con-

ducted an e thnographic study to u nderstand the users

and created the concept of the too l that supports fa-

mily cooperating work through the UXs including

phases of planning, experience, and retrospection.

Then, the tool was iteratively prototy ped and tested

so as to create a tool that enhances family communi-

cation by ena bling families to share past events and

intentions for the future.

In the test on the paper prototype, there were

parent-child inter a ctions in the tool. We presumed

that the tool was worth developing because partici-

pants of the test maintained motivation to use the pa-

per prototype. We e mbodied the tools as the second

prototy pe, which combines features of a calendar and

a photograph album. The second proto type demon-

strated usefulness in expre ssing family intentions and

experiences. User comments suggest that the tool is

compatible with mobiles. T he user can use photos and

materials that are selected or gathered with mobiles

by utilizing spare times. One of the participants f ound

visually that there had been few events in the past

month from the calendar (on which there were many

blanks), and was motivated to plan more events in the

future. We developed the third prototype b y impro -

ving th e usability of the second prototype and acces-

sibility to past experiences. By using the third pro-

totype, we held a workshop to observe actual usage

situation. In the workshop, pairs of a father and child

planned family events and m a de contents of past ex-

periences together by using the third prototype. We

identified the user acceptability of the third prototype

under te mporary use. Moreover, it was suggested that

it was essential to arouse the mothers’ interests to im-

prove accep tability in the home.

From the series of development processes, we

coordinated a user interface through which family

members can set plan s and share intentions, manage

schedules based on them, embed experien ces, and re-

trospect them. We used only qualitative approaches to

test prototypes in this paper. In the future, we plan to

evaluate the acceptability and usability of the tool es-

pecially based on quantitative indicators and c riteria

(Tullis and Alb e rt, 2013) such as que stionnaires and

operation logs. Moreover, we conducted user study

on limited subjec ts and conditions. To mention furt-

her validity of r e sults, it is needed to increase sample

size and test period. Size and composition of a group

are also controversial although we focu sed on pairs of

a parent and child in this paper.

CHIRA 2018 - 2nd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

42

REFERENCES

Abdullah, M. H. L. and Brereton, M. (2015). Mycalen-

dar: Fostering communication for children with au-

tism spectrum disorder through photos and videos.

In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Austra-

lian Special Interest Group for Computer Human Inte-

raction, OzCHI ’15, pages 1–9, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

Brown, S. L., Nobiling, B. D., Teufel, J. A., and Birch, D. A.

(2011). Are kids too busy? early adolescents’ percep-

tions of discretionary activities, overscheduling, and

stress. Journal of School Health, 81(9):574–580.

Brush, A. B. and Turner, T. C. (2005). A survey of per-

sonal and household scheduling. In Proceedings of

the 2005 International ACM SIGGROUP Conference

on Supporting Group Work, GROUP ’05, pages 330–

331, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Cao, X., S el len, A., Brush, A. B., Kirk, D., Edge, D ., and

Ding, X. (2010). Understanding family communica-

tion across time zones. In Proceedings of the 2010

ACM Conference on Computer Supported Coopera-

tive Work, CSCW ’10, pages 155–158, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Crabtree, A., Rodden, T. , and Mariani, J. (2004). Collabo-

rating around collections: informing the continued de-

velopment of photoware. In Proceedings of the 2004

ACM Conference on Computer Supported Coopera-

tive Work, pages 396–405. ACM.

Cul´en, A. L. and Følstad, A. (2014). Innovation in hci:

What can we learn from design thinking? In Pro-

ceedings of the 8th Nordic Conference on Human-

Computer Interaction: Fun, Fast, Foundational, Nor-

diCHI ’14, pages 849–852, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

Dam, E. and Siang, T. (2018). 5 stages in the de-

sign t hinking process. https://www.interaction-

design.org/literature/article/5-stages-in-the-design-

thinking-process, accessed 12 July 2018.

Forghani, A., Neustaedter, C., Vu, M. C., Judge, T. K., and

Antle, A. N. (2018). G2G: The design and evaluation

of a shared calendar and messaging system for grand-

parents and grandchildren. In Proceedings of the 2018

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Sy-

stems, CHI ’18, pages 155:1–155:12, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Frohlich, D., Kuchinsky, A., Pering, C., Don, A., and Ariss,

S. (2002). Requirements for photoware. In Procee-

dings of the 2002 ACM Conference on Computer Sup-

ported Cooperative Work, pages 166–175. ACM.

Granovetter, M. S. ( 1973). The strength of weak ties. Ame-

rican Journal of Sociology, 78(6):1360–1380.

Guy, I., Ronen, I., Kravi, E., and Barnea, M. (2016). Incre-

asing activity in enterprise online communities using

content recommendation. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum.

Interact., 23(4):22:1–22:28.

Heshmat, Y., Neustaedter, C., Yang, L., and Schiphorst,

T. (2017). Connecting family members across time

through shared media. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI

Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, CHI EA ’17, pages 2630–2637,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Inkpen, K., Taylor, B., Junuzovic, S., Tang, J. , and Veno-

lia, G. (2013). Experiences2Go: Sharing kids’ activi-

ties outside the home with remote family members.

In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Compu-

ter Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW ’ 13, pages

1329–1340, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Lucero, A., Holopainen, J., and Jokela, T. (2011). Pass-

them-around: collaborative use of mobile phones for

photo sharing. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Confe-

rence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1787–1796. ACM.

Lukoff, K., Moser, C., and Schoenebeck, S . (2017). Gen-

der norms and attitudes about childcare activities pre-

sented on father blogs. In Proceedings of the 2017

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Sy-

stems, CHI ’17, pages 4966–4971, New York, N Y,

USA. ACM.

Maguire, M. (2001). Methods to support human-centred

design. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud., 55(4):587–634.

Neustaedter, C. and Bernheim Brush, A. J. (2006). “LINC-

ing” the family: The participatory design of an inkable

family calendar. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Confe-

rence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI

’06, pages 141–150, New York, NY, U SA. ACM.

Neustaedter, C., Brush, A. J. B., and Greenberg, S. (2009).

The calendar is crucial: Coordination and awareness

through the family calendar. ACM Trans. Comput.-

Hum. Interact., 16(1):6:1–6:48.

Neustaedter, C., Pang, C., Forghani, A., Oduor, E., Hill-

man, S., Judge, T. K., Massimi, M., and Greenberg,

S. (2015). Sharing domestic life through long-term

video connections. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Inte-

ract., 22(1):3:1–3:29.

Nunes, M., Greenberg, S., and Neustaedter, C. (2008).

Sharing digital photographs in the home through phy-

sical mementos, souvenirs, and keepsakes. In Procee-

dings of the 7th ACM Conference on Designing Inte-

ractive Systems, pages 250–260. ACM.

Oduor, E., Neustaedter, C., Venolia, G., and Judge, T.

(2013). The future of personal video communication:

Moving beyond talking heads to shared experiences.

In CHI ’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, CHI EA ’13, pages 3247–3250,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Pan, R., Forghani, A., Neustaedter, C., Strauss, N., and

Guindon, A. (2015). The family board: An infor-

mation sharing system for family members. In Pro-

ceedings of the 18th ACM Conference Companion

on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social

Computing, CSCW’15 Companion, pages 207–210,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Roy, S. and Bhattacharya, U. (2015). Smart mom: An ar-

chitecture to monitor children at home. In Procee-

dings of the Third International Symposium on Wo-

men in Computing and Informatics, WCI ’15, pages

614–623, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Thompson, C. F., Goldwasser, E., Stanford, J., Syverson,

B., and Haley, K. (2017). Tweaking design thinking

Tool for Enhancing Family Communication through Planning, Sharing Experiences, and Retrospection

43

for strategic and tactical impact. In Proceedings of

the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Hu-

man Factors in Computing Systems, CHI EA ’17, pa-

ges 1303–1306, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Tullis, T. and Albert, W. (2013). Measuring the User Ex-

perience, Second Edition: Collecting, Analyzing, and

Presenting Usability Metrics. Morgan Kaufmann Pu-

blishers Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA, 2nd edition.

Wilson, C., Brereton, M., Ploderer, B ., Sitbon, L., and

Saggers, B. (2017). Digital strategies for supporting

strengths- and interests-based learning with children

with autism. In Proceedings of the 19th Internatio-

nal ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and

Accessibility, ASSETS ’17, pages 52–61, New York,

NY, USA. ACM.

CHIRA 2018 - 2nd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

44