Linguistic Diversity as Resource:

English Language Learners in a University Writing Center

Elizabeth Carroll

University Writing Center, Appachian State University, 218 College Street, Boone, North Carolina, 28608, USA

Keywords: English Language Learners, Multilingual writers, L2 Writers, International Students, Writing Centers,

Linguistic Diversity.

Abstract: In US colleges and universities, a growing number of English language learners (ELL) are using university

writing centers for assistance. However, despite the increase in linguistic diversity among students, writing

centers have been slow to respond to the needs of ELL students, approaching their language differences as

problems to fix rather than resources for learning. Through an institutional case study, this paper describes

how a writing center in a mid-sized, public university in the US has increased its support for ELL students

and linguistic diversity through changes in staffing, staff education, and outreach.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the United States, and around the world, the

number of English Language Learners (ELL) in

institutions of higher education is growing.

According to a recent joint report from the Institute

of International Education and the U.S. Department

of State (“IIE Releases Open Doors 2017 Data,”

2017), there were 85% more international students

studying at U.S. colleges and universities than were

reported a decade ago. Last year 1,078,822

international students were enrolled at U.S. colleges

and universities, and this number is expected to

grow exponentially in the coming years, not only in

U.S. but also worldwide (Council, 2012).

In institutions of higher education, this increase

in linguistic and cultural diversity is seen as

important for students and communities. Diversity is

valued so highly that it is often articulated as an

institutional goal, with targets set for increasing

diversity and measuring an institution’s progress

toward recruiting and retaining diverse students and

faculties. Driving this move toward greater

diversity is the belief that the presence of a more

diverse group of scholars enhances the educational

experience of all students and better prepares them

for participation in an increasingly multicultural,

multilingual, and global society.

Despite this emphasis on the importance of

diversity in the academy, however, out-dated

literacy policies and educational philosophies often

work against linguistic and cultural diversity in

higher education. This out-dated model of ELL

literacies relies on the assumption that linguistic

differences should be treated as deficiencies. In this

deficiency model, monolingual and Standard

English assumptions underpin institutional policies

and pedagogical approaches to literacy learning,

assumptions that work against valuing the linguistic

diversity ELL students (and others) bring to the

academy. In this way, linguistic diversity is seen by

many as a problem to be fixed rather than a resource

to be used in the service of learning.

In support of diversity, a growing body of

scholarship (Canagarajah, 2006) calls for institutions

to reject policies and practices that perpetuate the

deficiency model. Despite these research-based

arguments in favour of diversity, though, institutions

continue to operate using the deficiency model,

often because this research has not transformed

practice.

This article describes how one university writing

center changed policies and practices to support ELL

students by engaging difference as a resource for

education. Investigating Appalachian State

University’s Writing Center as an institutional case

study, this paper describes changes made to support

ELL students and to leverage diversity as a teaching

and learning resource. Programmatic and curricular

changes were made in writng center staffing, staff

education, and outreach using current research on

280

Carroll, E.

Linguistic Diversity as Resource: English Language Learners in a University Writing Center.

DOI: 10.5220/0008216900002284

In Proceedings of the 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference (BELTIC 2018) - Developing ELT in the 21st Century, pages 280-286

ISBN: 978-989-758-416-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

diversity and ELL. These changes were aimed at

improving instruction for ELL students and raising

awareness of linguistic diversity as a resource to be

cultivated and supported. This paper concludes with

specific actions writing center professionals can take

to assist ELL students’ writing and to support

linguistic diversity on our campuses.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 History

Writing centers have existed in higher education for

over a century, but most writing centers were started

in the past forty years in response to an influx of first

generation U.S. college students, many of whom

were considered underprepared for the demands of

college-level writing (EdD, 2009). Individualized

support through one-to-one tutoring was seen as the

best method for helping these underprepared writers

succeed.

While writing centers may have started to help

developmental English writers (assumed to be

monolingual), they have also been used heavily by

ELL students, who recognize the valuable

opportunities writing centers provide to practice the

conventions of academic English and to have

conversations in English about writing. Despite the

presence of ELL students, writing centers in some

areas of the US are still often assumed to be sites for

monolingual, English (only) speaking students. This

is not because writing center professionals intend to

ignore the needs of ELL writers; rather, it is because

of a lack preparation for TESOL and a monolingual

bias in the academic culture. In the U.S., most

writing center professionals are educated in English

departments and rhetoric and composition programs.

While these programs prepare to teachers and tutors

of writing, they often assume a monolingual

(English-only) speaking group of learners, and,

based on this assumption, they fail to provide

specific training in TESOL. With few exceptions,

TESOL programs are located in foreign language

departments, separated from English writing

instruction administratively and in the curriculum.

This bifurcation of TESOL and writing instruction

means that most writing center professionals lack

adequate training in working with ELL students.

2.2 Linguistic Diversity And Writing

Centers: Two Models

As sites dedicated to writing support in English,

writing centers are well-positioned to accommodate

the needs of ELL students. Through one-to-one

conferences with writing consultants, ELL students

benefit in several important ways through writing

center visits: 1) they have conversations about the

conventions and genres of academic English in the

context of their own writing projects; 2) they learn

about the cultural and linguistic differences between

their home countries and the U.S.; and 3) they

practice English in a natural context through

conversations with peer tutors (Rafoth, 2015).

In our work with ELL students, writing center

professionals can employ practices that are based on

assumptions from ither the deficiency model or the

resource model of difference. In a deficiency model,

writing centers function as sites for eradicating

language differences, where students come to erase

linguistic differences that mark them as non-native

English speakers. Alternatively, writing centers

using a resource model operate as sites where

linguistic differences are recognized as resources for

learning and communicating. This model

emphasizes collaboration between consultants and

writers that supports students’ voices, languages,

and ideas at the same time that students are learning

the discourses of academic English. The resource

model is based on a negotiation between consultants

and students, and this negotiation empowers ELL

students to make choices for themselves about

whether and how to present or erase linguistic or

cultural differences in their writing.

Unfortunately, though, because of monolingual

assumptions and a lack of education and training in a

resource model, writing centers often operate from

the deficiency model. Some of our writing center

training manuals and scholarship sometimes even

reinforce this view of ELLs’ writing differences as

problems to be fixed. Transforming writing center

practices to a resource model requires a different set

of principles that assume diversity is central, not

marginal, to literacy learning. Putting these

principles into practice was the focus of one writing

center’s program development and the subject of the

study at the center of this paper.

Linguistic Diversity as Resource: English Language Learners in a University Writing Center

281

3 RESEARCH METHOD

The study described in this paper focused on support

for ELL students in a university writing center. To

investigate the topic, the researcher relied on a case

study method of research, in which one institution,

Appalachian State University, served as the case

subject and the site of inquiry. It was chosen for two

reasons, the first was the researcher’s in-depth local

knowledge of the institution; the second reason was

because Appalachian State represents a specific kind

of case as an institution that struggles with issues

deriving from its homogeneous population and

resulting lack of linguistic and cultural diversity on

campus. Support for diverse populations, in this

context, is especially important and yet often

difficult to achieve. Research on Appalachian State,

therefore, yields insights for other homogeneous

institutions struggling to serve and support the needs

of diverse populations, as each institution is a “local

manifestation of more general social relations”

(Grabill, 2001).

The case study offered here should be considered

a research strategy as well as a research method.

While Appalachian State is the subject of the

inquiry, the object of the inquiry is providing

answers to questions concerning the role of writing

centers in supporting linguistic and cultural

diversity. The study was conducted over one

academic year, 2016-2017, in which writing center

professionals at Appalachian State attempted to

change practices to reflect current research on

diversity. The case study here is used as a form of

institutional critique, “a rhetorical methodology for

change” (Monske and Blair, 2016). This type of

research engages the institution’s policies,

curriculum, and professional documents as data,

interpreting and revising these materials to promote

change. This rhetorical methodology offers a

critique of current practices and exposes

opportunities for change (Monske and Blair, 2016).

A recent trend in articles, conference papers, and

book manuscripts in writing center studies calls for

increasing support for diverse populations; some

focus on multilingual writers (Lin and Deluca, 2017;

Newman, 2017; Phillips, 2017; Schreiber and

College, 2017) some on cultural and racial diversity

(García, 2017; Monty, 2013) and others on

marginalized populations (Babcock and Daniels,

2017). These writing center scholars call for greater

attention to issues of diversity and inclusion,

embracing a resource model of difference and

emphasizing the need for institutional change. The

results of this study add new knowledge to the

scholarly conversation about supporting diversity by

offering recommendations for changes to writing

center staffing, curriculum, and pedagogical

resources.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Cultivating Diversity at Appalachian

State University

By any measure, Appalachian State University is not

a diverse institution: Of the 18, 295 students enrolled

at Appalachian State University in 2016-2017, only

16% self-reported as ethnically or racially diverse

(non-white), and only 186, or about 1% of the

student body, identified as international students. In

recent years, the university has made progress in

diversifying its students and faculty, but the

institution continues to be overwhelmingly white,

middle-class, and monolingual (Appalachian State

University, 2017).

Although international students comprise only

around 1% of the student body at Appalachian, they

make up over 12% of the appointments in the

University Writing Center. Last year, out of 4448

total writing center appointments, 563 identified as

L2 English speakers.

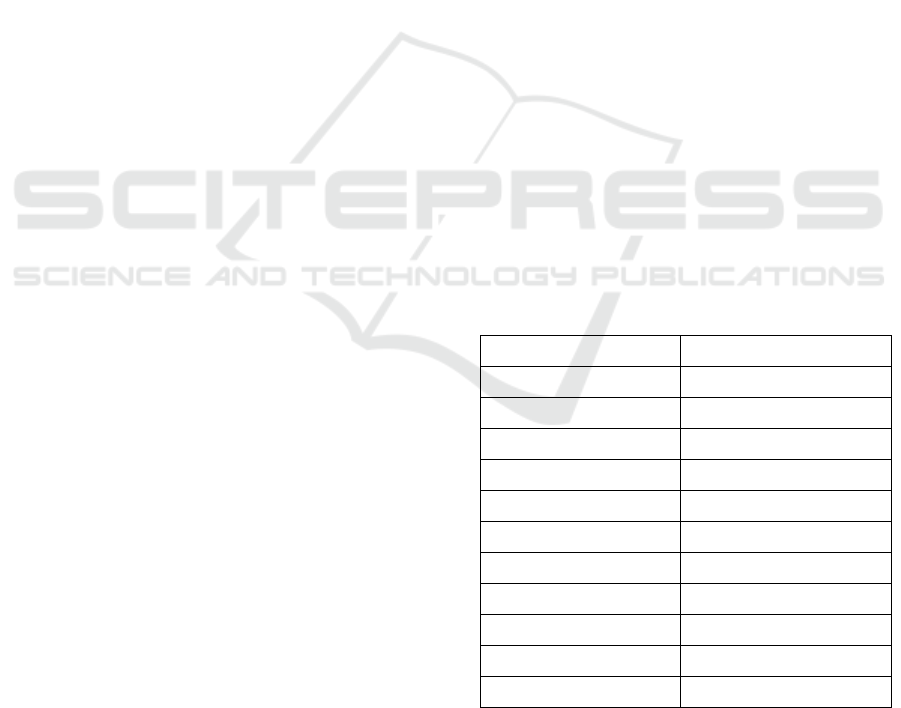

Table 1: ELL appointments in the University Writing

Center, 2016-2017.

Japanese

159

Spanish

119

Chinese

93

Other

62

Arabic

37

German

26

Korean

20

French

18

Farsi

12

Russian

8

Vietnamese

6

Portugese

3

In addition to making up 12% of all writing center

appointments, international students also tend to use

the writing center more frequently than their native

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

282

English speaking peers. Over half of the students

who visit the writing center only make one

appointment per year. By contrast, over 75% of ELL

students made more than one appointment per year,

and some visited the writing center weekly or

biweekly, with a total of more than 20 visits during

the course of a year. Using frequency of visits as a

measure, ELL students are the best users of writing

center services, taking advantage of our assistance

during all stages of the writing process and for all

types of writing assignments.

Although ELL students frequently use the

writing center as clients, they rarely apply for

employment in the writing center. As a result, the

staff of the writing center, historically and currently,

has not been ethnically or linguistically diverse.

Where we have had some success with diversifying

is with academic rank and discipline. The writing

center is staffed by writing consultants at all

academic ranks, and from different academic

disciplines across the university. Of the 29

consultants currently employed by the writing

center, 14 are undergraduate students, 9 are graduate

students, 4 are composition faculty, and 2 are

professional consultants. About half of the

consultants have a background in English studies,

and the others come from different disciplines,

including business, communications, education,

psychology, anthropology, history, music, and

foreign languages. This disciplinary diversity is not

matched by linguistic and ethnic diversity: Only 3

consultants are multilingual, able to speak and write

fluently in a language other than English, and only 2

consultants are non-white. In other words,

consultants may be diverse in their disciplinary

identifications and levels of expertise, but

consultants are not (yet) very diverse in terms of

their ethnic, racial, or linguistic backgrounds.

4.2 Toward A (Diverse) Writing Culture

Changes to Appalachian’s writing curriculum have

begun to change the culture of writing on our

campus, and these changes point toward some

promising opportunities for cultivating a more

diverse writing culture at the institution. In 2009,

Appalachian revised its general education

requirements to include a vertical writing

component. Every student in the university, in every

major, now takes a dedicated writing course in each

year of their undergraduate study. The first two

courses are taught by writing faculty in the rhetoric

and composition program, and the junior and senior

level courses are taught by faculty in the disciplines.

As students move through the writing curriculum,

they are expected to transfer writing knowledge to

new academic genres and contexts, culminating in a

senior capstone course, which demonstrates

students’ readiness to participate successfully in

their chosen academic and professional discourse

communities.

Developed by Dr. Georgia Rhoades,

Appalachian’s Writing Across the Curriculum

Director, the general education writing curriculum

presents challenges to students and teachers. Two

programs on campus support students and teachers

as they confront these challenges: the University

Writing Center, which assists students with their

writing, and the Writing Across the Curriculum

program, which supports faculty teaching the writing

courses. Together, these programs support the

vertical writing curriculum by giving teachers,

consultants, and students the resources they need to

succeed in teaching and learning in the writing

courses. These resources aim to demystify academic

discourses for all students, including those whose

home language is not standard English.

Before the changes in the writing curriculum,

students took two writing courses, both in the

English department. At that time, the University

Writing Center was also located in the English

department and primarily served students in English

composition courses. The revised general education

curriculum moved writing into all disciplines in the

university, and, around the same time, the University

Writing Center moved out of the English department

building and into a new library in the center of

campus. Moving writing out of English and into the

university enabled students to see writing as a

multidisciplinary tool, not a resource only for

English. This move toward recognizing and

supporting disciplinary differences in writing began

a culture change on our campus. This culture shift,

which has centered on engaging disciplinary

diversity in writing, promises also to point the way

toward greater recognition and support for linguistic

and cultural diversity as well.

Moving writing administratively and

physically out of the English department and into the

university library sent the message that writing is not

owned by any other single discipline. Moreover,

and of central importance for ELL students, as the

leaving the English department sent the message that

writing in the university isn’t owned by English.

This separation of English from writing opens new

possibilities of valuing and supporting linguistic and

cultural differences, much along with the

disciplinary differences in writing we now accept as

Linguistic Diversity as Resource: English Language Learners in a University Writing Center

283

part of general education. As a result of the writing

center’s move, writing center staff diversified in

terms of disciplinarity and in terms of academic rank

and levels of experience. The writing center staff

grew to include non-English majors as well as

professional consultants with more experience than

the undergraduate peer consultants that had formed

the majority of our staff before the writing center

moved from the English department.

4.3 Writing Center Staff Education

Cultivating a tutoring approach that engages

difference as a resource requires a revision to

consultant education and professional development.

As mentioned in the section on history, writing

center professionals often—and at all ranks, from

undergraduates to directors--lack a background in

TESOL. This lack of TESOL training, combined

with the monolingual assumptions guiding literacy

learning in the U.S., leaves writing center

practitioners unprepared for using linguistic

difference as a resource. This means that even those

who are teaching and mentoring new writing

consultants often fail to adequately prepare them to

work with ELL students. Even writing center

training manuals often treat differences as additives,

as though stereotyping writers into separate

categories--ELL writers, writers with disabilities,

developmental writers, etc—means that there is a

standard, monolingual writer who is typical, and

everyone else who is “different” must be treated to

address or remove the difference.

In a model of staff education that focuses on

treating difference as a resource, Blazer (2015) calls

for cultivating a “transformative ethos” in consultant

education. Her curricular model approaches

diversity and inclusivity as both ideals and resources

in teaching and learning. She offers examples of

regular reading, writing about, and discussion of

texts that engage with differences as resources. She

also asks consultants to develop materials and

resources for their work with students. Through

careful attention to connecting theories and practices

that support diversity, her model of staff education

challenges consultants to engage with linguistic and

cultural differences instead of avoiding or

eliminating them.

Adapting Blazer’s call for re-imagining writing

center staff education, we are placing diversity and

inclusion at the center of consultant training and

professional development at Appalachian. One

example of an excellent text that engages new

consultants and challenges them to re-think their

assumptions about academic English is Writing

Across Borders (“Writing Across Borders | Writing

Center | Oregon State University,” 2005), a short

video made by faculty at Oregon State University

that features international students talking about

their experiences with academic English in the U.S.

compared to writing in their native languages. After

watching the video, we discuss the issues raised in

the video, and students write about how they might

transform their tutoring practices based on some of

the ideas presented in the video. In reflective essays

at the end of their first semester as consultants, they

often report that the video opened their eyes to

cultural differences in writing that they were

unaware of before.

In addition to reading (or watching) challenging

texts, which are then discussed and written about,

our staff education curriculum, like Blazer’s model,

asks consultants to develop materials and resources

to support their work of tutoring. In the past few

years, our staff has developed some excellent

resources that support all writers, especially those

for whom academic English is a new discourse.

Led by writing consultant Dennis Bohr (“WAC

Glossary of Terms | Writing Across the Curriculum |

Appalachian State University,” 2015), our writing

center staff has produced a series of short

handouts—WAGS (Writing About Guidelines)—

that describe conventions and genres of writing in

various disciplines in the university. These handouts

are available in print format in the writing center for

consultants to use in their tutoring sessions. The

WAGS are also located on the writing center’s

website, which can be accessed by students,

consultants, and teachers to use in their teaching and

learning about disciplinary conventions. These

materials focus on demystifying academic writing,

and are helpful to all students, especially those

unfamiliar with conventions of academic writing in

the U.S.

Another WAC initiative that supports all

students, which is helpful to ELL students in

particular, is the development of the WAC Glossary

of Terms (“WAC Glossary of Terms | Writing

Across the Curriculum | Appalachian State

University,” 2015). This glossary, which is located

on the Writing Across the Curriculum website,

offers pages of writing-related terms, defined and

explained for students. This glossary of key terms

includes words used in discussing writing (revision,

invention, rhetoric). Establishing a common

vocabulary for talking about writing is one way

Appalachian has developed a culture of writing on

our campus. Learning English terms for discussing

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

284

writing holds particular value for ELL students,

whose English and writing knowledge is expanded

through learning vocabulary for thinking through

and discussing issues related to their academic

writing process.

In addition to supporting and mentoring

consultants in their work with ELL students, these

resources also give students language to express

themselves in conversations with consultants about

their challenges with writing. Developing materials

not only helps student writers, but it also assists

consultants in thinking through ways to discuss

differences and challenges writers bring to writing

center sessions.

4.4 Diversity Recruitment And Outreach

Tutoring methods and materials that support

diversity and inclusion form the basis of how writing

centers can use difference as a resource for learning.

This focus on tutoring is the most important

transformation we can make to support ELL writers.

Beyond the tutoring, however, we still need to find

ways to expand the ethnic and linguistic diversity of

the writing center staff. Given the lack of diversity

in the overall population at Appalachian, it is not

surprising that the writing center staff reflects that

lack of diversity. However, this homogeneity makes

it more, not less, important for us to lead efforts in

supporting diversity when and where we can.

Supporting diversity and inclusion in a writing

center means viewing diversity as central, not

marginal, to literacy learning. Although we have

more work to do, we have made some changes to

direct efforts toward diversifying our staff and

supporting diversity in our work with students.

These efforts include: 1) updating the writing

center’s mission statement and strategic plan to

emphasize the central importance of diversity; 2)

increasing outreach to students through a consistent

writing center presence at orientations and diversity-

related events on campus; 3) diversifying staff

through targeted recruiting of international students

and students of color; and 4) transforming consultant

education and professional development to focus on

pedagogical approaches that support teaching and

learning using diversity as a resource. These efforts

are meant to signal a genuine commitment to ELL

students and anyone else who might see themselves

as outsiders in the institution, marked by linguistic

or cultural differences.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Linguistic and cultural differences present

challenges for international students as they learn

conventions of academic English. As sites of

individualized writing instruction, and peer

collaboration, writing centers are ideal sites for

supporting ELL students in learning academic

discourses.

The linguistic and cultural diversity international

students bring to US universities enriches the

educational experience for all students. Creating a

culture of writing and a common language about

writing enables conversation and transfer of

knowledge across discursive boundaries, which

helps all writers, especially those who are new to the

cultures, genres, and conventions of U.S. academic

English. Over time, these changes in staffing,

education, and outreach have the potential to change

academic culture by challenging deficiency-based

assumptions about linguistic differences and

replacing those assumptions with policies and

philosophies that support diversity and inclusion.

REFERENCES

Babcock, R., Daniels, S., 2017. Writing Centers and

Disablity. Fountainhead Press, Southlake.

Blazer, S., 2015. Twenty-first Century Writing Center

Staff Education: Teaching and Learning towards

Inclusive and Productive Everyday Practice.

Writ. Cent. J. 35, 17–55.

Canagarajah, A.S., 2006. Toward a Writing Pedagogy of

Shuttling between Languages: Learning from

Multilingual Writers. Coll. Engl. 68, 589–604.

https://doi.org/10.2307/25472177

Council, B., 2012. The Shape of Things to Come: Higher

Education Global Trends and Emerging

Opportunities. The British Council, England.

EdD, N.L., 2009. The Idea of a Writing Laboratory.

Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale.

García, R., 2017. Unmaking Gringo-Centers. Writ. Cent.

J. 36, 29–60.

Grabill, J.T., 2001. Community Literacy Programs and the

Politics of Change. SUNY Press, Albany.

IIE Releases Open Doors 2017 Data [WWW Document],

2017. . iie. URL

https://www.iie.org:443/en/Why-

IIE/Announcements/2017-11-13-Open-Doors-

Data (accessed 7.27.18).

Linguistic Diversity as Resource: English Language Learners in a University Writing Center

285

Lin, H.C., Deluca, K., 2017. Educating and Recruiting

Multilingual and Other Graduate Students for

Writing Center Work. Writ. Lab Newsl.

Monske, E.A., Blair, K.L., 2016. Handbook of Research

on Writing and Composing in the Age of

MOOCs, Advances in Educational Technologies

and Instructional Design. IGI Global.

Monty, R.W., 2013. Theoretical Communities of Praxis:

The University Writing Center as Cultural

Contact Zone. The University of Texas at El

Paso, Texas.

Newman, M.B., 2017. Tutoring Translingual Writers: The

Logistics of Error and Ingenuity.

https://doi.org/10.15781/T2N010898

Phillips, T., 2017. Shifting Supports for Shifting Identities:

Meeting the Needs of Multilingual Graduate

Writers 14, 8.

Rafoth, B., 2015. Multilingual Writers and Writing

Centers, 1 edition. ed. Utah State University

Press, Logan.

Schreiber, B.R., College, B., 2017. Alternative Venues: an

Efl Writing Center Outside the University 14, 7.

Appalachian State University, 2017. Appalachian State

University / About [WWW Document]. URL

https://www.appstate.edu/about/ (accessed

7.27.18).

WAC Glossary of Terms | Writing Across the Curriculum

| Appalachian State University [WWW

Document], 2015. URL

http://wac.appstate.edu/writing-disciplines/wac-

glossary-terms (accessed 7.27.18).

Writing Across Borders | Writing Center | Oregon State

University [WWW Document], 2005. URL

http://writingcenter.oregonstate.edu/writing-

across-borders (accessed 7.27.18).

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

286