Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures

Hendi Pratama

1

, Joko Nurkamto

2

, Sri Marmanto

2

,

Rustono

3

1

Faculty of Language and Arts, Universitas Negeri Semarang

2

Postgraduate Program, Universitas Sebelas Maret

3

Faculty of Language and Arts, Universitas Negeri Semarang

Keywords: Idiomatic Implicatures, Conversational Implicatures, Pragmatics, Teaching Pragmatics

Abstract: Idiomatic expressions is treated as lexical components for decades. However, Arseneault (2014a) has

argued that idioms shall be investigated via their pragmatic properties. Hence, idioms may be classified as

an implicature from the point of view of pragmatics. Her argument has become the basis of our decision that

idiomatic implicature is one of the sub-species of conversational implicatures. Conversational implicatures,

in general, do not bring problems for native speakers but they become problematic for second language

learners. Through this study, we attempt to measure and explain second language learners' comprehension

on idiomatic implicatures. The inquiry covers to what extent second language learners comprehend

idiomatic implicatures and what strategies the learners to interpret this type of implicatures use. To answer

those questions, this research involves 110 students answering three questions containing idiomatic

implicatures. The findings can help second language instructors to redesign their curriculum regarding

idiomatic implicature learning in particular and English pragmatics in general.

1 PRAGMATICS AND

PRAGMATIC COMPETENCE

Bachman (1990) explicitly mentions that pragmatic

competence is an inevitable part of language

competence to be mastered by second language

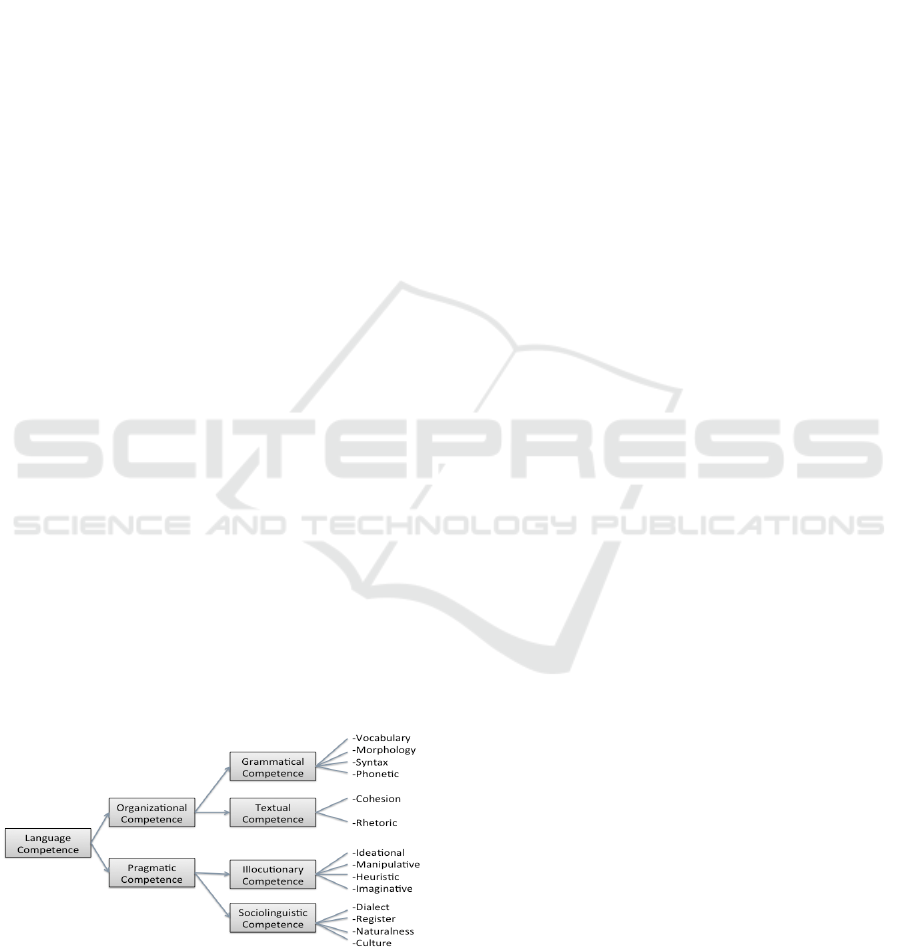

learners. According to her classification, there are

two competencies under language competence: (1)

organizational competence and (2) pragmatic

competence. The complete list of competencies can

be summarized as follows.

Figure 1: The Aspects of Language Competence

(Bachman, 1990).

The pragmatic competence laid out by Bachman

has two main strands: (1) illocutionary competence

and (2) sociolinguistic competence. Bachman’s

model of language competence has emphasized the

importance of pragmatics for second language

learners. Note to be taken, it seems that the field of

pragmatics is heavily related to illocutionary

competence than that of sociolinguistic competence.

Bachman is, in fact, the only expert who put

pragmatic competence as a sub-competence in

language competence. Other experts in EFL/ESL

like Canale & Swain (1980) and Celce-Murcia et al.

(1995) also argue that pragmatics is important for

second language learners but they did not mention

pragmatics explicitly and put it under different labels

instead.

Although it has been established that pragmatics

is an important competence for second language

learners, we have our own concern that second

language learners, especially in Indonesia, do not

have adequate mastery of English pragmatics. In the

previous study we have conducted, the learners have

a considerable amount of difficulty in

comprehending pragmatic features in English

(Pratama et al., 2016). The study involved 141

university students coming from three different

semesters: 57 freshmen, 41 sophomores, and 43

juniors. All of them are from the same English

department. Fifty-one multiple-choice questions

318

Pratama, H., Nurkamto, J., Marmanto, S. and Rustono, .

Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures.

DOI: 10.5220/0008217500002284

In Proceedings of the 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference (BELTIC 2018) - Developing ELT in the 21st Century, pages 318-327

ISBN: 978-989-758-416-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

were fdesigned to test the students’ understanding of

dialogues containing pragmatic features in English.

The results of the study are as follows.

Table 1: Summary of Pragmatic Test Results of Students

from Different Semesters.

Table 1 shows that second language learners in

the study have failed to comprehend some items.

From the 51 items, the 141 students can only answer

37.36 questions on average. If it is translated to real-

life situation, there is a 25% chance that students

will face communicational breakdown related with

dialogues containing pragmatic features in English.

Pragmatic competence can be broken down into

some important themes in pragmatics. According to

Horn & Ward (2006), there are some important

themes in pragmatics: (1) implicatures, (2)

presuppositions, (3) speech acts, (4) reference, (5)

deixis, (6) definiteness and indefiniteness, etc. Other

themes like politeness and cross-cultural pragmatics

can also be added to that list (Leech, 1983).

However, according to Levinson (1983), only

implicature has a very important role in pragmatics

because it is the most typical example of how

pragmatic force works.

2 PRAGMATICS FOR NON-

NATIVE SPEAKERS

At the early times when pragmatics was developed,

the pragmaticians focus their concepts of pragmatics

in monocultural society and the subjects are native

speakers of the language in that (Brown and

Levinson, 1987; Grice, 1975a; Sperber and Wilson,

1986a). In particular, the what-so-called

monoculture society is in fact Anglosaxonic culture

(Austin, 1962; Searle, 1985) . The paradigm was

slowly shifting and later on in 1980s there were

some pragmatics experts who raised their objections

on that narrow limitation of pragmatics. The experts

started to think that pragmatic research dealing with

Anglo speakers context cannot be generalized

universally for other research which involves

different types of speakers coming from different

cultural backgrounds (Kádár and Mills, 2011;

Wierzbicka, 2003). As parts of that movement, a

new generation pragmaticians have started

pragmatics competence research on non-native

speakers (Bardovi-Harlig, 2010; Kasper and Rose,

1999). The realm of foreign language learners

pragmatics has then become a denser body of

knowledge in 1990s and the field has been popularly

called interlanguage pragmatics (Leech, 2014). As

the domination of English as lingua franca in many

places around the world (Canagarajah, 1999),

interlanguage pragmatics' subjects have been

dominated by non-native speakers of English (Blum-

Kulka et al., 1989a; Schauer, 2009a). Research in

interlanguage pragmatics covers a number of

subthemes which are explored by different

researchers around the world (Bardovi-Harlig,

1999). Those subthemes include the following

subjects but not limited to pragmatics development,

pragmatics teaching, speech acts, speech situation,

pragmatics strategies, pragmatics resistance,

pragmatic research methodology, politeness and

implicatures. Among those subthemes, there is a

theme which is already overdiscussed namely

'speech acts' (Bataller, 2010; Bella, 2012a; Lee,

2011a; Nadar, 1998; Nguyen, 2008a; Schauer,

2009b; Wijayanto et al., 2013). Speech acts have

become particularly popular because in 1980, Blum-

Kulka et al. (1989a) has created a speech act

realization taxonomy which worked well among

academics and most researchers in pragmatics that

time are more willing to use their taxonomy. The

taxonomy has been well-documented in a project

called Cross-Cultural Speech Act Realization Project

(CCSARP). In their publication, Blum-Kulka et

al.(1989b) have made an invitation and challenge for

researchers around the world to conduct speech acts

realization codification in their own countries. The

invitation and challenge have been received well by

pragmaticians around the world. Thus, other

subthemes other than speech acts are still

worthwhile to be discussed and gaps are still

available to fill.

One out of some subthemes that needs more

attention and discussion in research is non-native

speakers' implicature. Studies taking the theme of

non-native speakers' implicature are still rare and

some improvements in the current theories and

findings are still welcome.

The last time research on non-native speakers’

implicature has been conducted thoroughly. It was

Participants

N

Mean

Std. Deviation

Semester 2

57

35.6842

7.33669

Semester 4

41

37.1707

6.93146

Semester 6

43

39.7674

5.43287

All

141

37.3617

6.85907

Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures

319

through studies administered by (Bouton, 1994) and

(Rover, 2005). Until then, detailed discussions

regarding non-native speakers' implicatures are

almost nonexistent. In Indonesia, there is one study

conducted by (Chandra, 2001a) dealing with non-

native speakers' implicatures but the study only

involves ten respondents and the approach used was

very limited. We personally think that opportunities

to conduct research on non-native speakers

implicatures are still wide open.

Pragmatics skills of non-native speakers may

come in two forms: receptive skills and productive

skills. Receptive skills include listening and reading

while productive skills include speaking and writing.

Previous studies in non-native speakers pragmatics

mostly focus on productive skills and less in

receptive ones (Bouton, 1994; Chandra, 2001a;

Kubota, 1995; Lee, 2012a; Murray, 2011; Rover,

2005; Soler, 2005). This gap provides a good reason

for the researchers in this study to conduct a research

on receptive skills.

This research mainly deals with receptive

strategies of non-native speakers in comprehending

conversational implicatures in English. Most of the

studies available are dealing with productive

strategies (Bada, 2010; Chen, 2015; Nguyen, 2008b)

and only a few are discussing the receptive strategies

(Chandra, 2001a; Lee, 2012a). Lee (2012b) uses

Language Processing Model by Bialystok (1993a)

and Chandra (2001b) uses the theory from (Sperber

and Wilson, 1986b). Other than (Bialystok, 1993b)

and (Sperber and Wilson, 1986b) receptive strategies

are still open for other theories to be adapted to

explain the phenomena.

There is also an overly used instrument in

interlanguage pragmatics and the instrument is

called discourse completion task (DCT) (Bella,

2012b; Lee, 2011b; Rose, 2009). This is a quite

strange phenomenon because there are a number of

alternatives available. Pragmatics research might use

role play (Félix-Brasdefer, 2007), discussion

(Nguyen, 2008b), verbal protocol (Lee, 2012a),

comprehension tests (Soler, 2005), in-depth

interview (Yates and Major, 2015), questionnaire

(Nguyen, 2008b)story telling (Bada, 2010) and

natural data recording (Economidou-Kogetsidis,

2013). DCT is an instrument that represents 40% of

interlanguage pragmatics studies.

3 IMPLICATURES AND

IDIOMATIC IMPLICATURES

An implicature is a pragmatic phenomenon in which

a speaker uses a coded utterance to deliver his intent

without explicitly mentioning it in his utterance

(Grice, 1975b). Using a method of inference and

common background knowledge, a hearer or more

are able to comprehend the message. The following

is the example of a dialogue containing an

implicature.

Alan : Are you going to Paul's party?

Barb : I have to work.

(Davis, 2014)

Alan asks a question to Barb. The question is

straightforward and Barb is supposed to say yes or

no. However, in this instance, Barb chooses to

answer using non-straightforward fashion. Her

answer implies that she would not come to the party.

Alan, using a method of inference and certain

background knowledge can interpret a particular

message that Barb would not come to the party.

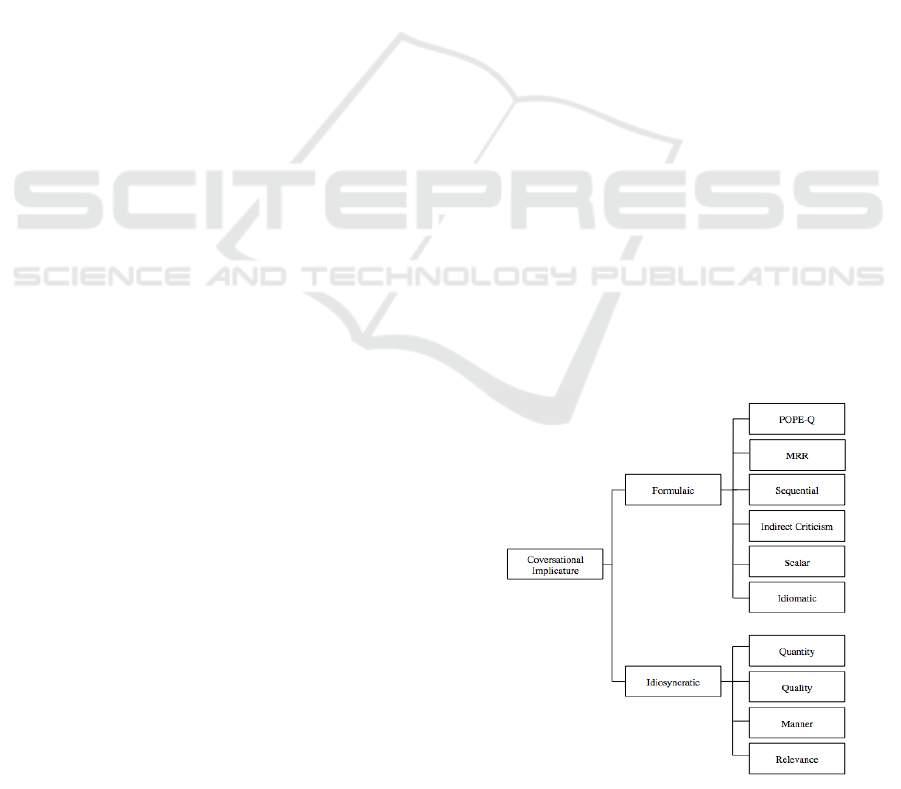

From our previous research (Pratama et al.,

2017), we have classified ten types of implicatures

according to the classifications established by

(Grice, 1975b), (Bouton, 1994) and (Arseneault,

2014b). Those ten types of implicatures are POPE-

Q, Indirect Criticism, Sequential, Minimum

Requirement Rule, Scalar, Idiomatic, Quantity,

Quality, Manner and Relevance. The full taxonomy

can be illustrated in the Figure 2.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

320

Figure 2: The Taxonomy of Implicatures for Second

Language Learners.

Among other works related to implicatures, the

work by (Arseneault, 2014b) mainly attracts our

attention. She argues that idiomatic expressions may

work as implicatures as well. Idiomatic expressions

have given clue to an utterance that the utterance

itself may contain an implicit message. This pattern

suits the definition of an implicature.

In order to understand the nature of the

implicatures taxonomy, the following table provides

the implicatures division, definition, and example.

Table 2: Implicatures' division, definition, and example

(Pratama et al., 2017).

Implicature

Remarks

Example

POPE-Q

Implicature

using rhetoric

question

John: Would

you like to go

to the beach?

Arthur: Is the

Pope Catholic?

Minimum

Requirement

Rule (MRR)

Number

mentioned by

the speaker

implicitly

means the

minimum

number

John: I need a

place with fifty

seats for my

son’s birthday

party.

Arthur:

McDonald’s

has fifty seats.

Sequential

Implicature

indicating the

order of events

Skeeter: OK,

how about we

just take walks

in the park and

go to the war

museum?

Wendy: Now

you're talking.

Indirect

Criticism

Implicature

indicating

criticism

without being

to explicit

Mr. Ray: Have

you finished

with Mark's

term paper

yet?

Mr. Moore:

Yeah, I read it

last night.

Mr. Ray: What

did you think

of it?

Mr. Moore:

Well, I thought

it was well

typed.

Scalar

Implicature

using modality

Dan: Oh

really? Does

he like them?

Gretta : She.

Yes, she seems

to.

Idiomatic

Implicature

using idioms

and/or

idiomatic

expressions

John: I think I

am still buying

the house for

us although

it’s next to a

toxic waste

dump.

Kelly: Have

you lost your

mind?

Quantity

Implicature

relying on

manipulation of

quantity maxim

Tim: So what

do you do?

Mary: I'm a

reader at a

publisher.

Tim: No! Do

you read for a

living?

Quality

Implicature

relying on

manipulation of

quality maxim

Chuck: Hey!

For the record,

every time I

laughed at one

of your jokes, I

was faking it.

Larry: You're a

monster!

Manner

Implicature

relying on

manipulation of

manner maxim

Griffin: Would

you marry me?

Stephanie:

Look, Griffin,

I know it

shouldn't

bother me that

you're a

zookeeper, but

it kind of does.

And when we

first started

dating, I just

assumed that

you would turn

into the guy

that I'd always

dreamed of

being with.

But...

(the

implicature is

“no”)

Relevance

Implicature

relying on

manipulation of

relevance

maxim

Mr. Andrew:

Where is my

box of

chocolate?

Mrs Andrew:

The children

were in your

room this

morning.

Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures

321

4 METHODS

This research is designed to answer two questions:

(1) to what extent second language learners

comprehend idiomatic implicatures? and (2) what

strategies are used by the learners to comprehend

this type of implicatures? In order to answer those

questions systematically, three dialogues containing

idiomatic implicatures to be tested to our

respondents are prepared. The following are the

three items included in our instruments.

Item 1

Context: John and Kelly are engaged. They are

talking about their future.

John: I think I’m still buying this house although it’s

next to a toxic waste dump.

Kelly: Have you lost your mind?

Question: What does Kelly’s statement mean?

a. Kelly disagrees with John’s idea.

b. Kelly agrees with John’s idea.

c. Kelly asks John if he is crazy.

Item 2

Context : Johnson is Angela’s best friend. Angela is

a psychologist. Johnson takes his friend, Charlie, to

consult with Angela.

Johnson: Nice to see you. Charlie, this is

Angela. Angela, this is Charlie. He's

my college roommate.

Angela: Nice to meet you, Charlie.

Johnson: Well, thanks for seeing us on such

short notice.

Angela : Why don't you guys come in and

make yourselves comfortable?

Question: What does Angela’s last statement

mean?

a. Angela does not let Johnson and Charlie in.

b. Angela is surprised by Johnson’s and

Charlie’s appearance.

c. Angela invites Johnson and Charlie to sit

down.

Item 3

Context : Sonny and Julian are father and son.

Because of a particular reason, Sonny confiscated

Julian’s toy.

Sonny: Give me that!

Julian: You just killed me.

Sonny: So what? Relax, you'll play later.

Julian: You can't tell me what to do. (Yelling)

Question: What does Julian’s last statement mean?

a. Julian thinks that his father does not have the

right to give an order.

b. Julian thinks that his father does not have any

ability to give an order.

c. Julian is not in the mood to relax.

Those three items were tested to 110

respondents. There are 40 respondents from English

department, 32 respondents from international class

majoring in Law and Engineering, and 38

respondents from regular Economics major. The

students coming from English department are taught

in English and they study English as their major.

The students from international classes are

Indonesians who are taught in English but their

major is not English. The students from regular class

are taught in Indonesian. One week after they did the

test, the researchers recalled 18 students to be

interviewed using Think Aloud Protocol (TAP).

TAP is a method of interview, which allows the

respondents to say out loud, what their minds

currently say (Ericsson and Simon, 1993). TAP is

conducted to answer the second question of this

study.

To codify the data, the researchers utilize the

taxonomy of strategies by (Vandergrift, 1997).

However, because the fact that Vandergrift's

taxonomy is mainly related with listening, only

some aspects of the strategies are fitted in this study.

The possible strategies used by the learners are:

(1) Inference: using the available information in the

dialogue to guess the part the learner does not

understand.

a. Linguistic Inference: using the words he

knows to guess on the words he does not

know.

b. Extralinguistic Inference: using the

relationship of the speakers, other parts of

the question, or other concrete situation to

guess the part that he does not understand.

c. Inter-part Inference: using markers that

show the relationships between utterances

and then guessing the meaning of the

utterance using those relationships.

(2) Elaboration: using the knowledge outside the

dialogue and relate it with the knowledge within

the dialogue in order to know the meaning of the

exchange.

a. Personal elaboration: using personal

experience.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

322

b. World elaboration: using general

knowledge around us.

c. Academic elaboration: using

knowledge gain from academic

situation.

d. Question elaboration: using chain

questions to guess the answer

e. Creative Elaboration: creating stories

or unique point of view to guess the

meaning.

f. Imagery: using picture or mental

visuals to represent information coded

to separate category

(3) Summarization: making mental or written

summary of the information in the dialogue

(4) Translation: translating the target language to the

mother language word by word.

(5) Transfer: using the knowledge of the mother

language to facilitate the understanding of target

language.

(6) Repetition: reading aloud the dialogue to

understand the meaning.

(7) Grouping: to call information based on other

information with similar attribute.

(8) Deduction/Induction: Consciously applying rules

that have been learnt or developed by himself to

understand the dialogue.

All responses from the TAP are recorded and

then interpreted using Vandergrift's taxonomy

above. The following transcript can illustrate the

technique of data reading and analysis.

Context: Johnson is a good friend of

Angela. Angela is a psychologist. Johnson brought

his friend Charlie to consult with Angela.

Johnson: Nice to see you. Charlie, this is

Angela. Angela, this is Charlie. He's my college

roommate.

Angela: Nice to meet you, Charlie.

Johnson: Well, thanks for seeing us on such short

notice.

Angela: Why do not you guys come in and make

yourselves comfortable?

Question: What is Angela's final say?

a. Angela does not allow Johnson and Charlie

to enter.

b. Angela was surprised by Johnson and Charlie

c. Angela invites Johnson and Charlie to sit

down.

(Instrument A Problem 16)

ATOP1 : Because of Angela's statement "..come in

make yourselves comfortable?"

It means she let them in

INT : do you think we that phrase in Bahasa ?

ATOP1 : anggap rumah sendiri (come in, make

yourself at home)

(Respondent ATOP1 Data 16)

According to the responses by respondent

ATOP1 and elicitation questions given by the

interviewers, there is a strong possibility that the

respondent uses the knowledge from Bahasa

Indonesia and the knowledge is being transferred to

English. Evidently, ATOP1 recognizes Indonesian

expression 'anggap rumah sendiri' as similar with the

English expression of 'make yourselves

comfortable''. This type of technique is called

'transfer' according to Vandergrift's strategy

categorization.

All data were treated the same way as the

example above so that all strategies used by all 18

respondents can be recapped and analyzed.

5 LEARNERS'

COMPREHENSION OF

IDIOMATIC IMPLICATURES

The number for correct implicature items answered

by the respondents represents comprehension of

idiomatic implicatures in this study. After the

respondents’ works are checked for the correctness

of the answers and then recapped, the following data

can be presented here.

Figure 3: The summary of respondents’ results on

idiomatic implicatures.

There are three items of idiomatic implicatures

presented to 110 students; three is the maximum

point and zero is the minimum point. According to

the results, all students on average can answer 2.5

2.73

2.66

2.13

2.5

Group 1

(N=40)

Group 2

(N=32)

Group 3

(N=38)

ALL (N=110)

Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures

323

items correctly. The group from English department

got the best result with 2.73 on average. The group

from international classes achieves a slightly

different result with 2.66 on average. The group

from regular Economics class suffers the most. They

got only 2.13 on average. There are two points to be

taken from those results. First, target language

exposure in formal classrooms is possible to be an

important factor for the learners to be successful in

comprehending idiomatic implicature. Second,

compared with other types of implicatures such as

POPE-Q (Pratama, 2017a) and Indirect Criticism

(Pratama, 2017b), idiomatic implicatures can be

categorized as relatively easy implicature to

comprehend by second language learners. In the

previous studies, POPE-Q implicatures recorded

2.02 on average and indirect criticism recorded 1.61

on average. All indexes are based on three as

maximum score.

There are three items are tested in this study.

Each item has its own level of difficulty reflected by

the respondent scores.

Table 3: Item difficulty based on respondents' scores

Item ID

Percentage of respondents

who answer correctly

Item 1

75%

Item 2

90%

Item 3

85%

Item 1 contains the idiom 'have you lost your

mind?'. Item 2 contains the idiom 'make yourself

comfortable'. Item number 3 contains the idiomatic

expression 'you can't tell me what to do'. According

to the data, the most difficult idiomatic implicature

to interpret is 'have you lost your mind?'. and the

easiest idiomatic implicature is 'make yourself

comfortable'. There are some possible answers to

explain this phenomenon. The first possibility is that

for Indonesian students 'make yourself comfortable'

is more salient and frequent than 'have you lost your

mind'. This explanation is adapted from the input

and attention theory such as that of (Schmidt, 1995).

Second explanation is that the lexical and

grammatical components of item 1 have consumed

more mental capacity than those of item 2. This

explanation owes its credit to relevance theory

(Sperber and Wilson, 1986b). Both explanations

have not been tested empirically and follow up

research needs to be conducted to provide a more

accurate explanation.

6 LEARNERS' STRATEGIES TO

COMPREHEND IDIOMATIC

IMPLICATURES

In an effort to understand the strategies used by the

learners in comprehending idiomatic implicatures,

the researchers have utilized a Think Aloud Protocol

to 18 respondents. Nine respondents come from the

high proficiency group and the other nine are from

the low proficiency. Using this arrangement, it is

able to contrast the strategies used by high

proficiency group and low proficiency group. The

following is the recapitulation of strategies used by

both groups.

Table 4: Recapitulation of strategies.

Strategies

High Profi

Ciency

Low Profi

ciency

Linguistic

Inference

3

5

Extralinguistic

Inference

3

2

Between parts

inferencing

1

0

Personal

Elaboration

0

0

World Elaboration

2

0

Academic

Elaboration

0

0

Questioning

Elaboration

1

0

Creative

Elaboration

5

1

Imagery

0

0

Summarization

0

0

Translation

6

6

Transfer

6

2

Repetition

1

0

Grouping

0

0

Deduction/Inductio

n

15

7

*Random Guessing

6

It can be seen from the table above that high

proficiency students are willing to try different types

of strategies. The high proficiency group tries nine

out of fifteen strategies possible while the low

proficiency only utilizes six of them. Deduction/

induction has been the favorite strategy for both high

proficiency or low proficiency group with obvious

differences. Deduction/induction in high proficiency

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

324

group often leads to correct answers while the same

strategy used by low proficiency leads to wrong

answers. There are some strategies that are never

utilized by both groups: personal elaboration,

academic elaboration, imagery, summarization and

grouping.

There is a new strategy coming up during the

TAP session and it only applies to the low

proficiency group. This strategy involves random

guessing. This strategy never appears in high

proficiency group. It seems that it is easier for the

low proficiency group to frustrate and give up. Even

when the interviewer tries very hard to convince the

respondent to state their strategies, they choose to

give up and admit that they just guess the answer

randomly. Such feature never takes place in high

proficiency group.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This research revolves around two main questions

since the very beginning. The first question is to

what extent second language learners comprehend

idiomatic implicatures. Based on the findings,

second language learners with high exposure to

English in the classroom can interpret idiomatic

implicatures easier than those from low exposure

classrooms. Compared with other types of

implicatures, idiomatic implicatures are considered

relatively easy. The second question of the research

is what strategies used by the learners to

comprehend this type of implicatures. The findings

show that high proficiency group learners are more

likely to try more various types of strategies (9 out

of 15) compared with the low proficiency group (6

out of 15). Furthermore, there is an emergent

strategy coming up only in the low proficiency

group namely random guessing.

The implications of this study put the burden to

language teachers to use English as language of

instructions as consistent as possible. We can safely

say that, at least from this study, exposure in the

formal classroom plays an important role to improve

the learners understanding of English implicature.

Attention shall be given to students with low

proficiency because they are prone to frustration and

have a tendency to give in their efforts to

comprehend implicatures.

REFERENCES

Arseneault, M., 2014a. An Implicature Account of Idioms.

International Review of Pragmatics 6, 59–77.

https://doi.org/10.1163/18773109-00601004

Arseneault, M., 2014b. An implicature account of idioms.

International Review of Pragmatics 6, 59–77.

Austin, J.L., 1962. How to do things with words. Oxford

Publication Press, Oxford.

Bachman, L.F., 1990. Fundamental considerations in

language testing. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bada, E., 2010. Repetitions as vocalized fillers and self-

repairs in English and French interlanguages. Journal

of Pragmatics 42, 1680–1688.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.10.008

Bardovi-Harlig, K., 2010. Exploring the pragmatics of

interlanguage pragmatics: Definition by design.

Pragmatics across languages and cultures 7, 219–259.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., 1999. Exploring the interlanguage of

interlanguage pragmatics: A research agenda for

acquisitional pragmatics. Language Learning 49, 677–

713. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00105

Bataller, R., 2010. Making a request for a service in

Spanish: Pragmatic development in the study abroad

setting. Foreign Language Annals 43, 160–175.

Bella, S., 2012a. Pragmatic development in a foreign

language: A study of Greek FL requests. Journal of

Pragmatics 44, 1917–1947.

Bella, S., 2012b. Pragmatic development in a foreign

language: A study of Greek FL requests. Journal of

Pragmatics 44, 1917–1947.

Bialystok, E., 1993a. Metalinguistic awareness: The

development of children’s representations of language.

Bialystok, E., 1993b. Metalinguistic awareness: The

development of children’s representations of language.

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., Kasper, G., 1989a. Cross-

cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Ablex

Pub.

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., Kasper, G., 1989b. Cross-

cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Ablex

Pub.

Bouton, L.F., 1994. Can NNS Skill in Interpreting

Implicature in American English Be Improved through

Explicit Instruction?--A Pilot Study.

Brown, P., Levinson, S.C., 1987. Politeness: Some

universals in language usage. Cambridge university

press.

Canagarajah, A.S., 1999. Interrogating the “native speaker

fallacy”: Non-linguistic roots, non-pedagogical results.

Non-native educators in English language teaching

7792.

Canale, M., Swain, M., 1980. Theoretical bases of

communicative approaches to second language

teaching and testing. Applied linguistics 1, 1–47.

Celce-Murcia, M., Dörnyei, Z., Thurrell, S., 1995.

Communicative competence: A pedagogically

motivated model with content specifications. Issues in

Applied linguistics 6, 5–35.

Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures

325

Chandra, O.H., 2001a. Pemahaman implikatur percakapan

bahasa Inggris oleh penutur asli Bahasa Indonesia.

Universitas Indonesia.

Chandra, O.H., 2001b. Pemahaman implikatur percakapan

bahasa Inggris oleh penutur asli Bahasa Indonesia.

Universitas Indonesia.

Chen, Y., 2015. Developing Chinese EFL learners’ email

literacy through requests to faculty. Journal of

Pragmatics 75, 131–149.

Davis, W., 2014. Implicature, in: Zalta, E.N. (Ed.), The

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics

Research Lab, Stanford University.

Economidou-Kogetsidis, M., 2013. Strategies,

modification and perspective in native speakers’

requests: A comparison of WDCT and naturally

occurring requests. Journal of Pragmatics 53, 21–

38.

Ericsson, K.A., Simon, H.A., 1993. Protocol analysis:

Verbal reports as data (revised edition). Bradford

books/MIT Press, Cambridge.

Félix-Brasdefer, J.C., 2007. Pragmatic development in

the Spanish as a FL classroom: A cross-sectional

study of learner requests. Intercultural pragmatics

4, 253–286.

Grice, H.P., 1975a. Logic and conversation, in: Cole, P.,

Morgan, J. (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics Volume 3:

Speech Act. Academic Press, New York.

Grice, H.P., 1975b. Logic and conversation, in: Cole, P.,

Morgan, J. (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics Volume 3:

Speech Act. Academic Press, New York.

Horn, L.R., Ward, G., 2006. The handbook of

pragmatics. Blackwell Publishing, Maiden.

Kádár, D.Z., Mills, S., 2011. Politeness in East Asia.

Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, G., Rose, K.R., 1999. Pragmatics and SLA.

Annual review of applied linguistics 19, 81–104.

Kubota, M., 1995. Teachability of Conversational

Implicature to Japanese EFL Learners. IRLT

(Institute for Research in Language Teaching)

Bulletin 9, 35–67.

Lee, C., 2012a. A preliminary study of the thinking

processes and speech act comprehension patterns

of Contonese learners of English. Lodz Papers in

Pragmatics 8, 209–231.

Lee, C., 2012b. A preliminary study of the thinking

processes and speech act comprehension patterns

of Contonese learners of English. Lodz Papers in

Pragmatics 8, 209–231.

Lee, C., 2011a. Strategy and linguistic preference of

requests by Cantonese learners of English: An

interlanguage and crosscultural comparison.

Lee, C., 2011b. Strategy and linguistic preference of

requests by Cantonese learners of English: An

interlanguage and crosscultural comparison.

Leech, G., 2014. The Pragmatics of Politeness Oxford

Studies in Sociolinguistics. Leech.–Oxford: OUP.

Leech, G.N., 1983. Principles of pragmatics. Longman,

New York.

Levinson, S.C., 1983. Pragmatics (Cambridge textbooks

in linguistics).

Murray, J.C., 2011. Do Bears Fly? Revisiting

Conversational Implicature in Instructional

Pragmatics. Tesl-Ej 15, n2.

Nadar, F.X., 1998. Indonesian learners’ requests in

English: A speech-act based study. Humaniora 61–

69.

Nguyen, T.T.M., 2008a. Criticizing in an L2: Pragmatic

strategies used by Vietnamese EFL learners.

Nguyen, T.T.M., 2008b. Criticizing in an L2: Pragmatic

strategies used by Vietnamese EFL learners.

Pratama, H., 2017a. Indonesian students responses to

POPE-Q implicature, in: The 8th International

Seminar Of Austronesian And Nonaustronesian

Languages And Literature. Universitas Udayana,

Denpasar.

Pratama, H., 2017b. EFL students’ misidentification of

criticism implicatures, in: UNNES International

Conference on ELTLT (English Language Teaching,

Literature, and Translation). pp. 224–227.

Pratama, H., Nurkamto, J., Marmanto, S., Rustono, R.,

2016. Length of study and students’

comprehension of English conversational

implicature, in: Prasasti. Universitas Sebelas Maret,

Surakarta, pp. 368–373.

Pratama, H., Nurkamto, J., Rustono, Marmanto, S., 2017.

Second language learners’ comprehension of

conversational implicatures in english. 3L:

Language, Linguistics, Literature 23.

https://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2017-2303-04

Rose, K.R., 2009. Interlanguage pragmatic development

in Hong Kong, phase 2. Journal of Pragmatics 41,

2345–2364.

Rover, C., 2005. Testing ESL Pragmatics. Peter Lang,

Frankfurt am Main.

Schauer, G., 2009a. Interlanguage pragmatic

development: The study abroad context.

Continuum, New York.

Schauer, G., 2009b. Interlanguage pragmatic

development: The study abroad context.

Continuum, New York.

Schmidt, R., 1995. Consciousness and foreign language

learning: A tutorial on the role of attention and

awareness in learning. Attention and awareness in

foreign language learning 9, 1–63.

Searle, J.R., 1985. Expression and meaning: Studies in

the theory of speech acts. Cambridge University

Press.

Soler, E.A., 2005. Does instruction work for learning

pragmatics in the EFL context? System 33, 417–

435.

Sperber, D., Wilson, D., 1986a. Relevance:

Communication and cognition. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

Sperber, D., Wilson, D., 1986b. Relevance:

Communication and cognition. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

326

Vandergrift, L., 1997. The comprehension strategies of

second language (French) listeners: A descriptive

study. Foreign language annals 30, 387–409.

Wierzbicka, A., 2003. Cross-cultural pragmatics. Walter

de Gruyter Inc.

Wijayanto, A., Laila, M., Prasetyarini, A., Susiati, S.,

2013. Politeness in Interlanguage Pragmatics of

Complaints by Indonesian Learners of English.

English Language Teaching 6, 188–201.

Yates, L., Major, G., 2015. “Quick-chatting”,“smart

dogs”, and how to “say without saying”: Small talk

and pragmatic learning in the community. System

48, 141–152.

Non-Native Speakers Understanding on Idiomatic Implicatures

327