Confirmatory Factor Analysis Post-traumatic Growth Inventory

among Domestic Violence Survivor

Diah Rahayu

1 2

, Hamidah

1

, and Wiwin Hendriani

1

1

Faculty of Psychology,Airlangga University, Jl. Airlangga No. 4-6, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Social and Political Sciences,Mulawarman University,Jl. Kuaro, Samarinda, Indonesia

Keywords: Confirmatory

Factor Analysis, DomesticViolence, Post-Traumatic Growth.

Abstract: Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory was a measurement tool to reveal the extent of the ability of the victim of

traumatic events in feeling the positive influence regarding the event. The samples of this study were

victims of domestic violence. One of the measurement tools to identify the impact of traumatic event was

Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI). Did PTGI have domains or factors that describe growth

conditions on the victim of domestic violence? Which domain factor affected PTGI the most? We used CFA

with structure equation modeling (SEM) program. With 201 respondents were qualified in the screening

process using the domestic violence measurement tool.The respondents’ age ranged from 18 to 26 years of

age. The process of analysis was conducted using AMOS program. The results showed that the absolute fit

measures met the requirement (GFI = .968; NFI = .965 and AGFI = .904), with the value of p = .0043 or p

<.005, indicating that PTGI dimension or indicator was consistent with latent variable and the significance

score. This could be inferred that the domain factors of PTGI were able to describe post-traumatic growth

on victim of domestic violence. The most influential and contribute indicator was openness to new

possibilities

.

1 INTRODUCTION

Traumatic events (such as cronical disease, traffic

accident, losing a loved one, divorce, etc.) could

cause negative emotional and psychological

condition that would eventually lead to maladaptive

behavior and aversive conditions(Taku, Tedeschi,

Cann, & Calhoun, 2009). Domestic violence could

lead to trauma,since it occur within the family and

the actorbeing a close relative. However, not all

traumatic conditions resulted in maladaptive

behavior. Based on a study conducted by Tedeschi

(1999), there were individuals who were able to

experience positive growth,therefore theybecame a

stronger person after experiencing traumatic events.

According to a theory proposed by Calhoun and

Tendeschi (1998), post-traumatic growth (PTG) was

a condition where an individual experience a

significant positive change as the result of struggle

in harsh life experience. The operational definition

of post-traumatic growth was an individual

condition measured through Post-Traumatic Growth

Inventory (PTGI)scale based on five dimensions,

which were Relating to Others, New Possibilities,

Personal Strength, Spiritual Chang, and

Appreciation of Life, with a total of 21 items.

Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory was used by

several researchers with different stressor

backgrounds, among individuals that experienced

accident or disability (Calhoun, Cann, Tedeschi, &

McMillan, 2000; Snape, 1997; Znoj, 1999),

individuals that were exposed to war (Powell,

Rosner, Butollo, Tedeschi, & Calhoun, 2003),

cancer and breast cancer patients(Bellizzi & Blank,

2006; Cordova, Cunningham, Carlson, &

Andrykowski, 2001; Tomich & Helgeson, 2004).

Domestic violence cases in PTG research were rare

cases, therefore this studyfocused on domestic

violence. Researches in PTG mostly discussed

generally traumatic cases and was not specific to a

particular setting, for example other than domestic

violence, the researches were also focused on

individual abuse or collective abuse that were

simultaneously non-specific on particular settings

(Dekel, Mandl, & Solomon, 2011; Hall, Saltzman,

Canetti, & Hobfoll, 2015; Kunst, 2010, 2011;

Woodward & Joseph, 2003). A specific explanation

regarding domestic violence was provided by Kunst

276

Rahayu, D., Hamidah, H. and Hendriani, W.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Post-traumatic Growth Inventory among Domestic Violence Survivor.

DOI: 10.5220/0008588202760282

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 276-282

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

(Kunst, 2010, 2011). Therefore, researchers were

interested in discussing PTG which was more

focused on cases of domestic violence which was

based on data that were increasing. Several studies

argued that this tool had a moderately good

reliability score. A research conducted on subject

experiencing traumatic situation during the last three

years found the validity of 0.90, and the retest

reliability with a distance of two months was 0.71

(Calhoun et al., 2000). Kunst (2010) found the PTGI

reliability value of 0.95 in samples experiencing

domestic violence and being left in the shelter. Other

studies were conducted on samples experiencing

trauma without looking at background of the trauma

or stressor. For instance, Duan (in Duan, Guo, &

Gan, 2015) adapted PTGI method in Chinese

language or culture, and the study found the

reliability value of 0.80. PTGI tool measurement

was also used and adapted in several countries, such

as China (Duan et al., 2015), Taiwan (Su & Chen,

2015), Turkey (Arikan & Karanci, 2012),Israel (Hall

et al., 2015)and Indonesia, with the sample

background of earthquake survivors in Bantul

(Urbayatun & Widhiarso, 2012). Based on those

studies, PTGI as a measurement tool could be used

to measure PTG attributes with different cultural

background after going through the adaptation

process. In this study, the PTGI went through a

language and cultural adaptation process prior to the

confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) process

thatfocused on domestic abuse cases.

CFA was a tool for researchers to confirm

whether the indicator variables (indicator was

determined by a strong theory) could be used to

confirm a latent variable (Ferdinand, 2014). CFA

was analyzed using SEM program, as it could

describe the combination between exploratory

analysis with multiple regression (Ulman, 2001 as

citedinSchreiber, Stage, King, Nora, & Barlow,

2006). The purpose of this study was to find out

whether PTGI indicators could confirm PTG

variables on the female victims of domestic violence

in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, and which indicators

had more influence towards the latent variable.

Based on the purpose, the authors proposed a

hypothesis: PTGI indicators affected how PTG’s

latent variables were formed.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

Participants in this research were women around 18-

25 years old of age(early adult age) in an East

Kalimantan university. They had experienced

traumatic events of domestic violence. Domestic

violence level was screened using the question list in

brief autobiograpy (besides self-identity such as age,

race, marital status) filled by participants. The

selected participants were those who entered the

middle adult criteria because the classic Eriksonian

conceptualizations of young adulthood suggested a

developmental path that involved exploration and

then commitment to a certain identity, including

sexual identity in the realm of love and professional

identity in the realm of work (Arnett, as cited in

Mayseless & Keren, 2014). The traumatic condition

caused by domestic violence was believed to affect

the decision or readiness in forming relationships

and the commitment for marriage. Therefore, a

screening process by completing autobiography and

meeting the requirements as victims of domestic

violence and PTG was conducted to the potential

subjects.

2.2 Measurement

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi &

Calhoun, 1996)was a scale consisting of 21 items

with five subscales: Relating to Others (seven

items), New Possibilities (five items), Personal

Strength (four items), Spiritual Change (two items),

and Appreciation of Life (three items). Taku et al.

(2008) reported moderately high internal consistency

for total PTGI scores and subscales, being: PTGI (α)

= 0.90, Relating to Others (RTO) = 0.85, New

Possibilities (NP) = 0.84, Personal Strength (PS) =

0.72, Spiritual Change (SC) = 0.85, and

Appreciation of Life (AOL) = 0.67. Each item was

assessed using a 6-point Likert scale, with a value

ranging from 0 (I did not experience this change as a

result of my crisis) to 5 (I experienced a huge

change as a result of my crisis). The total scores

obtained ranged from 0 to 105.

2.3 Data Analysis

The study used structural equation modeling (SEM)

with confirmatory analysis factor (CFA) to find out

whether the model was fit or not. The results were

processed using AMOS statistic program. CFA

allowed the researcher to test the hypothesis of the

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Post-traumatic Growth Inventory among Domestic Violence Survivor

277

relation between observed variables and the

underlying latent constructs. The researcher used the

knowledge of theory, empirical research, or both, to

postulate the relationship pattern a priori, before

testing the hypothesis statistically (Suhr, 2006). CFA

was performed by first determining the hypothesis to

estimate the population covariance matrix compared

to the observed covariance matrix. Technically, the

researchers wanted to minimize the differences

between the estimated and observed matrices

(Schreiber et al., 2006). Maximum likelihood was

the most popular normal theory estimator

(DiStefano, 2002).

3 RESULT

3.1 ConfirmatoryFactorAnalysis

(CFA)

This study proposed two hypotheses: (1) H0 = there

was no influence of PTGI indicators as observer

variable toward PTG latent variable; and(2) H1 =

there was influence of PTGI indicators as observer

variable toward PTG latent variable. In order to test

the hypotheses using CFA, Netemeyer, Bearden, and

Sharma (2003) used the general CFA model

evaluation with the following five criteria: (1) model

convergence and acceptable range of parameter

estimate; (2)fit indices; (3) significance of parameter

estimates and related diagnostics; (4) standardized

residual and modification indices; and (5)

measurement invariance across multiple samples.

The evaluation of CFA was conducted using two of

the criteria above, which were criterion (1) and (2).

Both criteria were used because they were

commonly used and quite appropriate to find out the

fit model in CFA analysis (Sharif et al., 2011; Taku,

Cann, Calhoun, & Tedeschi, 2008).

3.1.1 Model Convergence and An

Acceptable Range of Parameter

Estimate

Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) involved a

recurrent/iterative process, in which the observed

covariance matrix was compared with the theoretical

matrix to reduce the difference (residue). This step

aimed to determine whether the CFA converged or

not. Although the data in PTGI was ordinal data (0-

5), they could be treated as interval data for

maximum likelihood in each model. From the data,

it was expected that each observed variable would

contain factors that measure latent variables and

would not contain other factors (Taku et al., 2008).

The value of MLE included standardized

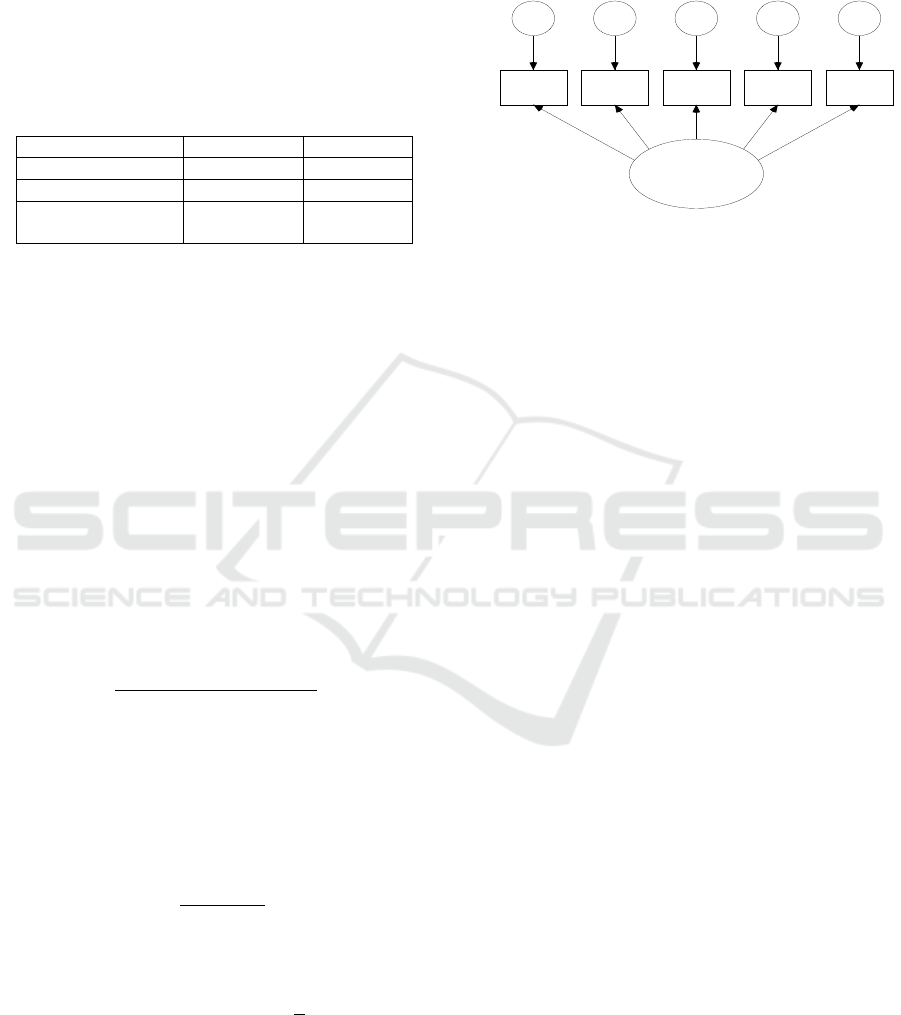

parameters. Table 1 provides the estimate values:

Table 1: Standardized Regression Weights: (Group

number 1 - Default model).

Estimate

RTO <--- PTG

NP <--- PTG

PS <--- PTG

SC <--- PTG

AOL <--- PTG

.5874

.8557

.8452

.6077

.8370

3.1.2 Fit Indices

Fit indices in this study classified CFA’s goodness

of fit data into absolute fit indices, comparative or

incremental, and parsimony based fit indices. The

value of absolute fit measured degree of freedom

(df) = 5,the estimated value of chi square

𝜒

=

17.1084with p=0.0043 0.05could be considered as

significant (Ho, 2006). The value ofgoodness of fit

index (GFI) = 0.9678 and goodness of fit index

(AGFI) = 0.9037. The value of GFI and AGFI in this

study ranged between 0 and 1, with a value of ≥0.90.

This indicatedthat the model was fit to the data(good

fit) (Sharif et al., 2011). Root mean square residual

(RMR) = 0.4208, root mean square error of

approximation (RMSEA) = 0.110. The value of

RMR and RMSEA should be ≤0.05. However, in

this research, the value was greater than 0.05, Thus,

the value of RMR and RMSEA could not match/fit

the data (poor fit) (Netemeyer, 2003).Expected cross

validation index(ECVI) = 0.1855. The value was

considered sufficient as it was close to 1, so this

value showed poor fit model. Incremental fit

measured the value that included Normed Fit Index

(NFI) = 0.9654, Relative Fit Index (RFI) = 0.9309,

Incremental Fit Index (IFI) =0.9501 and

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.9750. The values in

this research had the same value of ≥0.90. Thus, it

showed that they were good models in matching the

data (good fit) (Netemeyer et al., 2003).

The value of Parsimony Fit Measures, which

consisted of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and

Consistent Akaike Information Criterion (CAIC),

were used to compare multiple models. The smaller

value indicated better capability in terms of

matching data than other models. In the evaluation

of this research, the values were:AIC model (37.10)

Saturated AIC (30) and Independence AIC

(505.012); CAIC model (80.141) Saturated CAIC

(94.549) and Independence CAIC (526.529). Both

values of AIC and CAIC were smaller than other

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

278

values, indicating that they fit to CFA PTGI model.

If PGFI had a greater value than other models with

values ranging between 0 and 1, it indicated that it

had better ability to match data than other models.

However, the value of PGFI = 0.3226, which was

smaller than RMR = 0.3226, so the model results

were not fit (Santoso, 2015). Table 2 provides the

results of the models.

Table 2: Akaike Information Criterion.

Model AIC CAIC

Default model 37.1084 80.1414

Saturated model 30.0000 94.5496

Independence

model

505.0120 526.5286

3.2 Convergent Validity and Construct

Reliability

Convergent validity could be seen from MLE value

or loading factor that presented in Table 1 or path

analysis in Figure 1. Loading factor in this study

hada value above 0.500, indicating that PTGI

indicators hadgood convergent validity (Netemeyer

et al., 2003). Construct reliability value

aimedtomeasure an item’s internal consistency of

the measuring instrument. Hair (as cited in

Netemeyer etal., 2003) agreed that the recommended

reliability threshold was0.70,while Bagozzi and

Ying (as cited in Netemeyer et al., 2003) set 0.60.

This construct reliability size, according to Hair (as

cited in Netemeyer et al., 2003),could be obtained

byFormula 1:

𝐶𝑅

∑

𝑆𝐿𝐹

∑

𝑆𝐿𝐹

∑

𝑒

.

(1)

Internal consistency could also be measured with

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) estimates. This

method wasused to assess the number of variants

processed by a series of items on a scale towards

measurement error. The AVE size was formulated

by Formula 2 (Hair, as cited in Netemeyer et al.,

2003):

𝐴

𝑉𝐸

∑

𝑆𝐿𝐹

𝑛

.

(2)

SLFi represented SLF value of i

th

, and n

th

showed

the number of latent or construct variable used to

measure its latent variable. Hair (as cited in Gio,

2017) asserted that AVE value > 0.5 indicates

adequate convergence. According to the

aforementionedFormula 1 and 2, it was obtained:

CR value = 0.829 and AVE = 0.572. This

indicatedthat reliability of PTGI measurement

instrument in this research was0.829 0.70, which

implied sufficient reliability. Moreover, the internal

consistency of 0.572 0.50 also showed sufficient

value.

Figure1: Path CFA PTGI.

4 DISCUSSION

This study aimed to examine the observer variable

ability in predicting PTG latent variable. The PTGI

observer variable encompassed Relating to Others

(seven items), New Possibilities (five items),

Personal Strength (four items), Spiritual Change

(two items), and Appreciation of Life (three items)

(Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). According to the

findings of the five indicators analysis, those items

could predict the PTG latent variable of domestic

violence victim sample in East Kalimantan.

Thisindicated that CFA PTGI was a

multidimentional measurement, regarding to its

factor structure and determined estimate values.

The goodness fit in this study was based on a

research conducted by Netemeyer et al. (2003),in

which fit model evaluation could be seen from the

number of ways. Likewise, this study employed

common ways to evaluate goodness fit, namely

estimate and fit indices. Overall, the findings

showed that CFA PTGI test on domestic violence

sample was significant and met the fit criteria. When

referring to fit indices values, such as GFI, AGFI,

which had a value of nearly 1, then the goodness fit

was fulfilled. Likewise, NFI, RFI, IFI and CFI

values werehigher than 0.90. Probability value of

Chi square was also significant (<0.05). These

findings were consistent with a study conducted by

Taku et al. (2008) which evaluated five PTG

indicators in American populationwhich had various

traumatic causes. Taku et al.’s (2008) study obtained

a significant and fit model.

The results of this study also showed that

construct validity on each indicator was quite

sufficient, although the Relating to Other (RTO)

PTG

.35

RTO

e1

.59

.73

NP

e2

.86

.71

PS

e3

.85

.37

SC

e4

.61

.70

AOL

e5

.84

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Post-traumatic Growth Inventory among Domestic Violence Survivor

279

value of 0.5874 was considered to have a small

contribution. RTO was a condition in which

individuals were able to establish good relationships

with people. In the case of domestic violence, the

condition of being in contact with another person

required more effort because the victims experience

anxiety and lose confidence in communicating with

others (Evans, Davies, &DiLillo, 2008). New

Possibility (NP)had the greatest contribution as

individuals had confidence in the new possibilities in

life. Individuals with high NP values generally

became more optimistic, extraversial and open to

new experiences. A study conducted by Tedeschi

and Calhoun (1996) found that women tended to

have a higher NP value than men.

In addition to PTGI’s indicator contribution, this

study also found reliability and good internal

consistency. This value could be seen from CR and

AVE values. The indicator values, CR and

AVE,were closely related to the sampling process

(Ferdinand, 2014). In this study,the sampling

processwas conducted by screening in order to get a

qualified research sample with quite extreme

domestic violence. The process wasconsistent with a

study conducted by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996),in

which theystated that individuals who had

experienced more extreme traumatic conditions

actually had higher PTGI value. Research by

Kleimand Ehlers (2009) suggested a curvilinear

relationship between PTG and PTSD, as well as

PTG and depression in survivors of interpersonal

violence. This curvilinear relationship indicated that

the intermediate level of traumatic disturbance was

optimal for the occurrence of PTG (Calhoun &

Tedeschi, 1998, 2004).

However, there were several studies that

reported no significant relationship between PTG

and critical condition (Borja, Callahan, & Long,

2006; Cobb, Tedeschi, Calhoun, &Cann, 2006;

Grubaugh & Resick, 2007; Kunst, 2010, 2011).

Calhoun and Tedeschi (2004) argued that

different findings of PTG aspects werepossible, as

this was very sensitive and related to cognitive

processes.It might also be influenced differently by

other variables. Calhoun and Tedeschi (as cited in

Taku et al., 2008) pointed out that when individuals

experience traumatic conditions and they constantly

contemplate (i.e. seeking or forming a new world

that is assumed to highlight positive aspects of the

experience),their thoughts about ways to understand

trauma would be more likely to reach PTG. Overall,

this study revealedthat PTGI indicators wereable to

predict PTGI latent variable. The sampling

processwas crucial for CFA statistical analysis

measurement as well as for the sample itself. It was

expected that this study could illustrate that PTGI

could be used in sample with traumatic condition

due to domestic violence. Further study needs to

measure traumatic level more specifically in order to

obtain a more profound analysis in terms of

traumatic level differences towards contribution of

PTGI indicators.

5 CONCLUSION

This study found that PTGI indicators of domestic

violence victims contibute to PTG latent

variable.This indicated that PTGI could be adapted

and implemented on respondents with different

cultures/cultural backgrounds. The results also

showed that PTGI could be used on specific cases

such as domestic violence. Other specific cases that

could cause traumatic conditions, such as disability

causing accidents, were potential research targets.

The authors hoped that the results were able to

provide other researchers with a clear portrayal that

the measurement domains in the development of

PTGI could contribute in diagnosing the potential of

growth in subjects with traumatic experiences. The

growth being: being able to be more open with

others, being appreciative of life, having inner-

strength, having an increase in spirituality, and

having a more positive viewpoint regarding the

future. The domains could be used as the benchmark

for individuals’ post-traumatic growth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The writers would like to thank to the Ministry of

Research, Technology, and Higher Education for

funding in this study and to the Psychology

Department of Faculty of Social and Political

Science of Universitas Mulawarman Samarinda.

REFERENCES

Arikan, G., Karanci, N., 2012. Attachment and Coping as

Facilitators of Posttraumatic Growth in Turkish

University Students Experiencing Traumatic

Events,Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13, 209-

225. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2012.642746

Bellizzi, K. M., Blank, T. O., 2006. Predicting

Posttraumatic Growth in Breast Cancer

Survivors,Health Psychology, 25(1), 47-56.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.47

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

280

Borja, S. E., Callahan, J. L., Long, P. J., 2006. Positive

and negative adjustment and social support of sexual

assault survivors, Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(6),

905-914. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20169

Calhoun, L. G., Cann, A., Tedeschi, R. G., McMillan, J.,

2000. A correlational test of the relationship between

posttraumatic growth, religion, and cognitive

processing,Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(3), 521-

527. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007745627077

Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G. (1998). Beyond Recovery

From Trauma: Implications for Clinical Practice and

Research,Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 357-371.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01223.x

Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., 2004. The Foundations of

Posttraumatic Growth: New

Considerations.Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 93-102.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501

Cobb, A. R., Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G., Cann,

A.,2006. Correlates of posttraumatic growth in

survivors of intimate partner violence,Journal of

Traumatic Stress, 19(6), 895-903.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20171

Cordova, M. J., Cunningham, L. L. C., Carlson, C. R.,

Andrykowski, M. a., 2001. Posttraumatic growth

following breast cancer: A controlled comparison

study,Health Psychology, 20(3), 176–185.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.20.3.176

Dekel, S., Mandl, C., Solomon, Z., 2011. Shared and

unique predictors of post-traumatic growth and

distress,Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 241-

252. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20747

Distefano, C. (2002). Structural Equation Modeling : A the

impact of categorization with confirmatory factor

analysis,Structural Equation Modeling, 9(3), 327-346.

https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0903

Duan, W., Guo, P., Gan, P., 2015. Relationships among

trait resilience, virtues, post-traumatic stress disorder,

and posttraumatic growth,PLoS ONE, May, 1-13.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125707

Evans, S. E., Davies, C., DiLillo, D., 2008. Exposure to

domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and

adolescent outcomes,Aggression and Violent

Behavior, 13(2), 131-140.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005

Ferdinand, A., 2014. Structural Equation Modeling dalam

penelitian manajemen. Semarang: Undip Press.

Gio, P. U., 2017.SEM dalam LISREL (Interpretasi Output

LISREL). Retrieved from

https://www.academia.edu/22099699/SEM_dalam_LI

SREL_Interpretasi_Output_LISREL, June 8, 2017)

Grubaugh, A. L., Resick, P. A., 2007. Posttraumatic

growth in treatment-seeking female assault victims.

Psychiatric Quarterly, 78(2), 145-155.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-006-9034-7

Hall, B. J., Saltzman, L. Y., Canetti, D., Hobfoll, S. E.,

2015. A longitudinal investigation of the relationship

between posttraumatic stress symptoms and

posttraumatic growth in a cohort of Israeli Jews and

Palestinians during ongoing violence,PLoS ONE,

April, 1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124782

Kleim, B., Ehlers, A., 2009. Evidence for a curvilinear

relationship between posttraumatic growth and

posttrauma depression and PTSD in assault

survivors,Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(1), 45-52.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20378

Kunst, M. J. J., 2010. Peritraumatic distress, posttraumatic

stress disorder symptoms, and posttraumatic growth in

victims of violence,Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(4),

514-518. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20556

Kunst, M. J. J., 2011. Affective personality type, post-

traumatic stress disorder symptom severity and post-

traumatic growth in victims of violence,Stress and

Health, 27(1), 42-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1318

Mayseless, O., Keren, E., 2014. Finding a Meaningful Life

as a Developmental Task in Emerging Adulthood: The

Domains of Love and Work Across

Cultures,Emerging Adulthood, 2(1), 63-73.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696813515446

Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., Sharma, S., 2003.

Scaling procedures: Issues and application,

California: Sage Publication Inc.

Powell, S., Rosner, R., Butollo, W., Tedeschi, R. G.,

Calhoun, L. G., 2003. Posttraumatic growth after war:

A study with former refugees and displaced people in

Sarajevo,Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 71-83.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10117

Santoso, S., 2015. AMOS 22 untuk Structure Equation

Modelling : Konsep dasar dan aplikasi. Jakarta: PT.

Elex Media Komputindo.

Schreiber, J. B., Stage, F. K., King, J., Nora, A., Barlow,

E. A., 2006. Reporting structural equation modeling

and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review.

Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-337.

https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Sharif, A. R., Ghazi-Tabatabaei, M., Hejazi, E.,

Askarabad, M. H., Dehshiri, G. R., Sharif, F. R., 2011.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the university student

depression inventory (USDI). Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 30, 4-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.001

Snape, M. C., 1997. Reactions to a traumatic event: The

good, the bad and the ugly? Psychology, Health &

Medicine, 23(3), 237-242.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548509708400581

Su, Y.-J., Chen, S.-H., 2015. Emerging posttraumatic

growth: A prospective study with pre-and posttrauma

psychological predictors,Psychological Trauma:

Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(2), 103-111.

https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000008

Suhr, D., 2006. Exploratory or confirmatory factor

analysis? Statistics and Data Analysis, 200-31, 1-17.

Taku, K., Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., 2008.

The factor structure of the posttraumatic growth

inventory: A comparison of five models using

confirmatory factor analysis,Journal of Traumatic

Stress, 21(2), 158-164.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20305

Taku, K., Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., 2009.

The culture of disclosure: Effects of perceived

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Post-traumatic Growth Inventory among Domestic Violence Survivor

281

reactions to disclosure on posttraumatic growth and

distress in Japan. Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, 28(10), 1226-1243.

Tedeschi, R. G., 1999. Violence transformed :

Posttraumatic growth in survivors and their societies

SOCIETIES, 4(October), 319-341.

Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G., 1996. The posttraumatic

growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of

trauma,Journal of Traumatic Stress,9(3), 455-471.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02103658

Tomich, P. L., Helgeson, V. S., 2004. Is finding something

good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among

women with breast cancer,Health Psychology, 23(1).

https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16

Urbayatun, S., Widhiarso, W., 2012. Variabel Mediator

dan Moderator dalam Penelitian Psikologi Kesehatan

Masyarakat, Jurnal Psikologi, 39(2), 180-188.

Woodward, C., Joseph, S., 2003. Positive change

processes and post-traumatic growth in people who

have experienced childhood abuse: Understanding

vehicles of change,Psychology and Psychoterapy:

Theory, Research and Practice, 76, 267-283.

https://doi.org/10.1348/147608303322362497

Znoj, H, J., 1999. European and American perspectives on

posttraumatic growth: A model of personal growth:

Life challenges and transformation following loss and

physical handicap. Paper presented at the Annual

Convention of the American Psychological

Association (107th), Boston, MA.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

282