The Effect of Psychological Capital on Work Engagement:

Investigating the Moderating Effect of Gender and Job

Muhammad Tamar and Hillman Wirawan

Department of Psychology Universitas Hasanuddin, Makassar, Indonesia

Keywords: PsyCap, work engagement, gender, job and moderation

Abstract : This study aims to investigate the effect of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) on Work Engagement and

examine the potential moderating effect of gender and job type. The effect of PsyCap on desired work

behavior and work attitude is ubiquitous. However, little is known whether the effect is consistent across

different gender and job type. This study employed a moderated multiple regression analysis to empirically

test the moderating effect of gender and job on PsyCap – Work Engagement relationship controlling the

effect of tenure, age and education. The data were collected from 466 participants who were registered as

full-time public transportation personnel (186) and nurses (280) in Makassar city. As predicted, the results

found that PsyCap contributed to employee Work Engagement (ΔR

2

= .11, β= .34, p< 0.01). The findings

also suggested significant cross-product of PsyCapxGender (ΔR

2

= 0.02, β= .13, p< 0.01) and PsyCapxJob

(ΔR

2

= 0.01, β= .14, p< 0.05). This study confirmed a number of previous findings where PsyCap

contributed to employee positive work attitudes. Further, this study added considerably important

information about the moderating effect of gender and job type on PsyCap and its consequences.

Discussion, limitation and future research direction are also included.

1 INTRODUCTION

There is growing evidence that many

organizations value significant impact of positive

organizational behaviors. Both private and public

sectors found the desired impact of positive

behaviors on employees’ outcomes as well as

organizational performance. One of well-known

findings of the positive organization movements is

the concept of work-engagement (Bakker and

Demerouti, 2008; Leiter and Bakker, 2010;

Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003). The positive behaviors

have brought many significant changes to the way

employers and business owners capture their

employees. There was a great change from seeing

employees as personnel or just ordinary workforce

to treating employees as one of organization/

business capitals (Lepak and Snell, 2002).

Psychological Capital or PsyCap for short

emerged as one of positive organizational

movements. Psychological Capital was coined to

refine the perception of human resources. The

ordinary ideas about human resources only put much

concern on workforce for organizations where

employers demand high task-completions.

Employees should not be treated as workers but also

part of organization’s capital. The idea of PsyCap

has emerged to confirm that people in organizations

are assets with their Psychological Capital.

Positive psychology and positive organizational

behaviors have encouraged the emergence of

PsyCap in organizations. Luthans, Youssef-Morgan,

& Avolio (2015) argued that PsyCap is one of the

most influential positive movements in the areas of

business and management. The study of PsyCap

identified four the most positive traits (i.e., Hope,

Optimism, Resilience, and Self Efficacy) that

potentially benefit positive employees’ outcomes

and organizational outcomes (Choi and Lee, 2014;

Peterson et al., 2011). It is plausible that positive

traits also drive positive employee’s outcomes and

help to fight negative outcomes. For instance, some

of the traits (e.g., Resilience) could help employees

to struggle during hard conditions and achieve better

results after series of failure.

The effect of PsyCap on employees and

organizational outcomes, as mentioned earlier, have

been documented by some researchers. First, the

effect of PsyCap benefits employee’s psychological

states. Youssef-Morgan & Luthans (2015)

postulated that employees with higher level PsyCap

Tamar, M. and Wirawan, H.

The Effect of Psychological Capital on Work Engagement: Investigating the Moderating Effect of Gender and Job.

DOI: 10.5220/0008591705350542

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 535-542

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

535

tend to possess better well-being. The positive traits

may have helped employees to cope with negative

emotions. As found by Rabenu, Yaniv, & Elizur

(2016), PsyCap was negatively associated with

stress, and it also favored employees to cope with

stress. Second, PsyCap also potentially strengthen

positive attitude in organizations. To illustrate,

previous findings have found the positive impact of

PsyCap on employee’s commitment and engagement

(Simons and Buitendach, 2013; Thompson et al.,

2015; De Waal and Pienaar, 2013). In addition,

PsyCap also supports positive behaviors such as

organizational citizenship behaviors (Pradhan, Jena

and Bhattacharya, 2016), satisfaction (Azanza,

Moriano and Molero, 2013), and performance (Sun

et al., 2011; Vanno, Kaemkate and Wongwanich,

2014).

Some studies have also found significant

contributions of PsyCap on mediating the effect of

leadership on positive employee’s outcomes

(Bouckenooghe, Zafar and Raja, 2015). Others also

found that PsyCap successfully mediated the

relationship between authentic leadership and

employees’ creativity (Zubair and Kamal, 2015). All

these findings suggested that PsyCap had some

important roles in organizations such as ensuring

positive psychological states, supporting positive

attitudes, and improve performance. It appears that

most studies in this area supported that PsyCap has a

significant contribution to employees and

organization desired outcomes.

The positive effect of PsyCap was found to be

consistent across different studies. Nevertheless,

some findings indicated some variations in using

PsyCap as a positive antecedent of many desired

outcomes in organizations. For example, the cross-

cultural PsyCap also had a positive effect on

employees working in different cultures (Reichard,

Dollwet and Louw-Potgieter, 2014). However, a

meta-analysis found some interesting facts that

PsyCap had a greater impact for US population than

other population, and industry type also moderated

the relationship between PsyCap and employees’

performance (Avey et al., 2011). The effect of

PsyCap on desired employees’ outcomes was more

powerful among US employees than non-western

countries (Reichard, Dollwet and Louw-Potgieter,

2014). The service-based industry showed stronger

correlations between PsyCap and performance and

other positive employees’ outcomes than the

manufacture employees. Considering these findings,

it is plausible to address a new direction of PsyCap

study.

While many scholars consistently documented

the positive effect of PsyCap, this study is intended

to focus on the moderating effect of gender and job

on the PsyCap - Work Engagement relationship.

There were two major issues in generalizing the

effect of PsyCap; first, PsyCap may have benefited

more men than women as some PsyCap components

were found to be stronger for men than women. In

organizations, female employees were found to be

higher on optimism while male employees were

better at resilience (Parthi and Gupta, 2016). This

empirical study confirmed a previous study where

Patton, Bartrum, & Creed (2004) investigated that

unlike men, women’s optimism directly predicted

their career goals. Second, as cited earlier, although

most organizations valued the positive effect of

PsyCap, some job type or industry type may benefit

the PsyCap more than others. Thus, this study will

also focus on the influence of job type on PsyCap.

The significant contribution of PsyCap also

found to be the antecedent of employees’ work

engagement (Avey et al., 2011; Simons &

Buitendach, 2013; Thompson et al., 2015).

However, taking the previous discussions into

account, the effect of PsyCap on Work Engagement

could be determined by some demographic variables

(e.g., gender and job type) as PsyCap functions

differently under different conditions. The effect of

PsyCap on Work Engagement may depend on

gender or job type. Gender and job type potentially

moderate the relationship between PsyCap and

employees’ work engagement.

The theory of Job Demand Resource (JD-R) can

explain the moderating effect of gender and job type

on PsyCap – Work Engagement relationship. The

(JD-R) theory stated that work engagement is

determined by employees’ resources (i.e., job and

personal resources) and job demand (Bakker and

Demerouti, 2008). Moreover, job demand may vary

across job type or industry type. For instance, some

researchers investigated the effect of PsyCap among

nurses and found the positive contribution of PsyCap

(Bradbury-Jones, 2015) while others also found the

different effect of PsyCap for police officers (Siu,

Cheung and Lui, 2014). Male and female employees

also have different perception towards job demand,

and in some cases, female employees may suffer for

more physical work demand than their male

counterparts (Aittomäki et al., 2005).

The theoretical background and previous findings in

this area direct this current study to investigate the

moderating effect of gender and job type on PsyCap

and Work-Engagement relationship. This study

hypothesized; 1) PsyCap significantly predicts

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

536

Work-Engagement (H1), and 2) both gender and job

type moderate the effect of PsyCap and Work

Engagement (H2).

, and 2) both gender and job type moderate the

effect of PsyCap and Work Engagement (H2).

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Participants were 466 employees (Male= 35% and

Female 65%). The participants worked full-time as

public transport personnel (N= 186) in Makassar

(one of the most populated cities in Indonesia) or

nurses (N= 280) in four different public hospitals in

Indonesia. These two organizations were chosen

because they represented two different job types.

The questionnaires were sent to the participants in

sealed envelopes including the consent form and

instructions on how to complete the questionnaires.

This study employed a two-wave data collection

technique to rule out any potential common method

bias. Common method bias could be caused by

collecting data from the same source at same time

(MacKenzie and Podsakoff, 2012). In the first wave,

the demographic data (i.e., tenure, gender, age,

education) and PCQ were sent to 760 participants.

These participants were asked to participate in the

second wave of data collection. The second wave

questionnaire consisting of Work-Engagement Scale

was sent to the participants two weeks later.

However, only 466 returned the questionnaire with

complete responses. In this case, only participants

who participated in the first and the second wave

data collections were included in the analysis.

2.2 Measures

Psychological Capital Questionnaire (Luthans,

Youssef-Morgan and Avolio, 2015) was used to

measure Participants’ level of PsyCap in six

different dimensions (i.e., Hope, Optimism,

Resilience, and Efficacy). The scale has 24 items

with six items for each dimension. In the previous

validation studies, the PCQ satisfied validity and

reliability standard for research purpose (Görgens-

Ekermans and Herbert, 2013; Antunes, Caetano and

Pina e Cunha, 2017). The initial Bahasa Indonesia

version of the PSQ was retrieved from the scale

publisher (Mind Garden). Although the publisher

had provided the Indonesia version, the authors

rechecked each item and asked two experts to judge

the quality of each item. After carefully evaluated

each item, using this current research data this study

found that Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

confirmed the model was close fit (RMSEA< .08)

with Alpha Cronbach coefficient of .81. The

findings indicated that the Indonesia version of PCQ

had the acceptable level of construct validity and

deemed reliable for research purpose. For the

demographic variables, the authors collected

information on gender, tenure, age, education. The

questionnaires were also coded for job types (i.e.,

public transport personnel or nurses). Work-

Engagement was measured using Work Engagement

Scale (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003). The

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) confirmed the

model was close fit (RMSEA< .08) with Alpha

Cronbach .82. “I am enthusiastic about my job” is

one of items in the scale. For the demographic

variables, the authors collected information on

gender, tenure, age, education. The questionnaires

were also coded for job types (i.e., public transport

personnel or nurses). The demographic data were

collected using self-report survey. Participant’s

gender and job type were investigated as moderating

variables while tenure, age, and education were

included as control variables.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Results

There were two main steps in analyzing the data.

First, a descriptive analysis was run to show

differences between mean scores for the variables.

This also included a set of bivariate correlations to

capture significant relationships among the

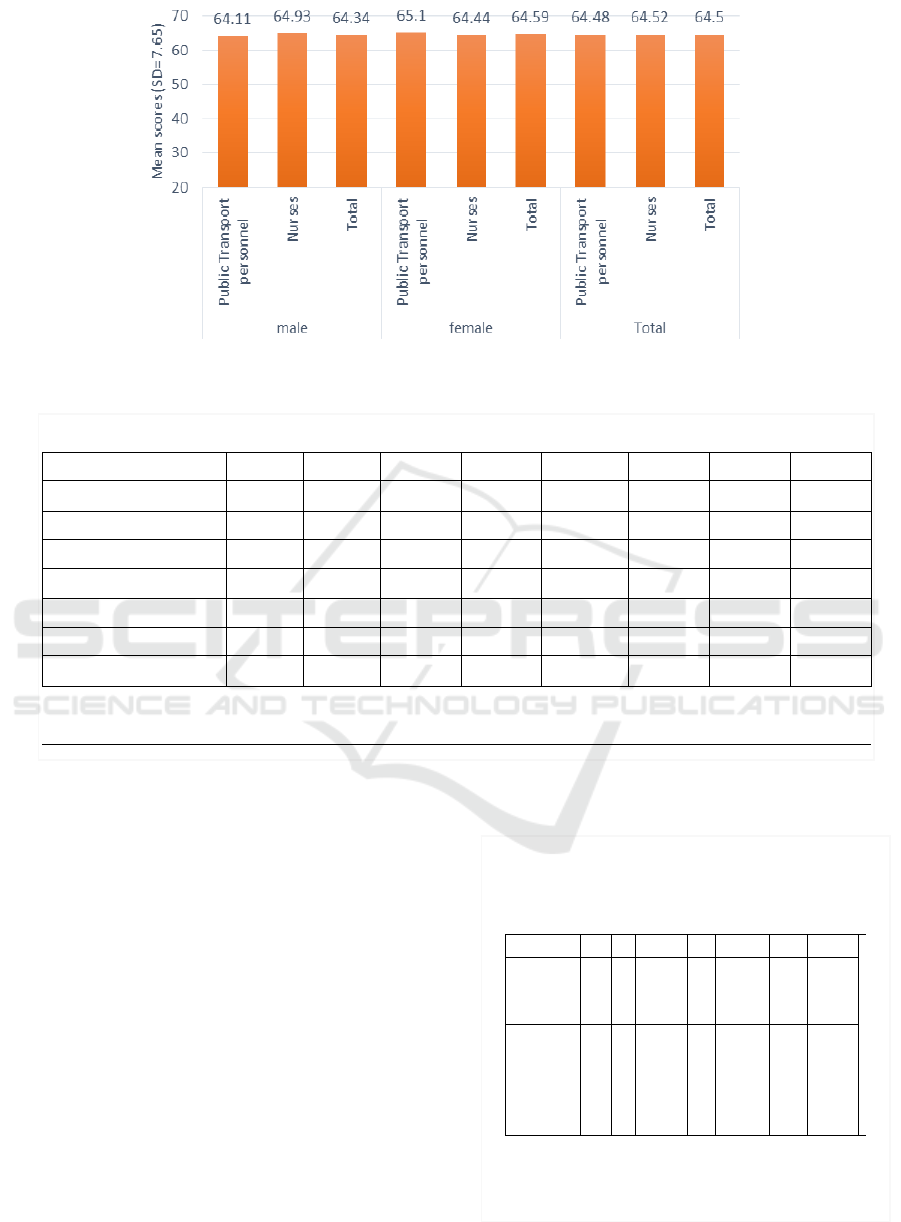

variables. The following two figures described

participants’ mean score for PsyCap and Work-

Engagement:

Figure 1: PsyCap mean scores.

The Effect of Psychological Capital on Work Engagement: Investigating the Moderating Effect of Gender and Job

537

Figure 1 showed that in the same job, male and

female PsyCap had only small differences.

However, employees in the public transportation

office tended to have a higher level of PsyCap than

the nurses. It influenced the total differences where

the public transport personnel had a higher level

PsyCap than nurses. For the gender comparisons,

male employees were slightly higher in PsyCap than

their female counterparts. In brief, the graph showed

a quite noticeable comparison across jobs and

genders.

Unlike the figure 1, the participants’ Work-

Engagement across genders and jobs tended to be

stable. The mean scores were closely ranged from

64.11 to 65.50 where the differences lower than a

half of the standard deviation. Regarding job type

and gender, no considerable differences should be

noted for the level of Work-Engagement. This

finding showed that job type, and gender did not

have significant influences on employees’ Work-

Engagement.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations.

M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Age 31.91 7.33

2. Tenure 7.89 5.50 .755

**

3. Education 2.77 1.01 .273

**

.291

**

4. PCQxGender 78.07 23.42 .032 .051 .237

**

5. PCQxJob 75.29 22.37 .217

**

.267

**

.638

**

.441

**

6. PCQtotal 47.51 5.19 -.088 -.086 -.137

**

.229

**

.014

7. WEtotal 64.50 7.65 -.027 .005 .083 .141

**

.139

**

.325

**

Note: N= 466, PCQ= Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PsyCap), WE= Work Engagement, M= mean, SD=

standard deviation,

**

p< 0.01

Table 2: Model Summary for PCQ Total as

Predictor for Work Engagement controlling

Tenure, Age and Education.

Model R R

2

A

dj. R

2

Δ

R

2

ΔF β T

Tenure

Age

Education

.10 .01 .01 .01 1.64 .04

-.09

.09

.61

-1.22

1.94

Tenure

Age

Education

PCQ

Total

.35 .12 .12 .11 59.69

**

.05

-.07

.13

.34

.78

-1.11

2.92

**

7.73

**

N

ote: N= 466,

**

p<0.01, β= Standardized Beta

Weight, SEE= Standard Error of the Estimate,

Adj.= Adjusted, Δ= change

Figure 2: WE mean scores.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

538

Table 2 also showed significant correlations

among variables. The participants’ Work-

Engagement were positively and significantly

associated with PCQxJob, PCQxGender, and total

PsyCap. The cross-product of the total PsyCap and

Job showed significant positive correlations with all

the study variables excluding the total PsyCap. The

correlation coefficients could provide an initial

indication that the interaction between PsyCap,

gender, and job potentially influenced the level of

employees’ Work-Engagement.

The descriptive analysis and the bivariate

correlations indicated that the interactions between

PsyCap and Gender (or Job) determined the effect of

PsyCap on employee’s Work-Engagement. To

examine the effect, Multiple Regression Analyses

with control variables were performed.

In the first Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA),

the first model only ran the analysis with the control

variables to test any significant effects of the

variables then the PCQ total (the total PsyCap) was

included in the second model. As predicted, tenure,

age, and education did not predict Work-

Engagement. In contrast, PsyCap added significant

incremental values (ΔR

2

= .11, p< .01) to predict

Work-Engagement after included in the model. In

the second model, Education also significantly

predicted Work-Engagement after PsyCap included

in the model. These findings confirmed the first

hypothesis that PsyCap contributed significantly to

employees’ Work-Engagement.

The second MRA also supported this study’s

second hypothesis. The cross-product of

PCQxGender (ΔR

2

= .02, p< .01) and PCQxJob (ΔR

2

= .01, p< .01) both showed significant incremental

values in predicting Work-Engagement. Also, none

of the control variables significantly predicted

Work-Engagement. These findings confirmed that

the interactions among employee’s PsyCap, Gender,

and Job predicted employee’s Work-

Engagement. Considering the mean scores in the

previous tables, PsyCap varies across gender and job

type.

Table 4. Conditional effect of PsyCap on Work

En

g

a

g

ement

Gende

r

Effe

ct

se t p

CI 95%

LL U

L

Male .32 .10 3.06 .00 .12 .5

3

Femal

e

.63 .08 7.50 .00 .46 .7

9

Job t

yp

e

PTP .18 .08 2.09 .04 .01 .3

4

1.02 .10 10.1 .00 .82 1.

Nurse 5 22

Note: PTP= public transport personnel, LL= lower

level, UL= upper level, CI= Confidence Interval

Table 4 showed the conditional effect PsyCap on

Work Engagement at different gender and job type.

For the gender, the results suggested that the effect

was stronger (0.63, p< 0.001) for female than for

male (0.32, p< 0.001) participants. For the job type,

Nurses showed higher effect (1.02, p< 0.001)

compared to public transport personnel (0.18, p<

0.05). Nevertheless, the significant effect of PsyCap

on Work-Engagement was consistently found across

genders and job types.

3.2 Discussions

This study aimed to investigate the effect of PsyCap

on Work-Engagement and to examine the

moderating effect of gender and job type on the

relationship. The positive contributions of PsyCap in

many desired employees’ outcomes have been

documented by scholars in the area of Psychology,

Management and Organization studies. Many

previous publications consistently supported the

argument that PsyCap had positive associations with

employees’ positive outcomes. According to the

positive organization movement, PsyCap also

positively influences employee’s Work-

Engagement. For this reason, many recent studies

aim to develop learning or training to support

employee’s PsyCap (Luthans et al., 2014, 2006,

2008; Reichard et al., 2014; Dello-Russo and

Stoykova, 2015).

Table 3: Model summary for the cross-

p

roduct o

f

PCQxGender and PCQxJob as predictors for wor

k

engagement controlling tenure, age and education.

Model R R

2

Adj.

R

2

ΔR

2

ΔF β t

Tenure

Age

Education

PCQxGender

.16 .03 .02 .02 7.23

**

.04

-.08

.06

.13

**

.61

-1.16

1.26

2.69

**

Tenure

Age

Education

PCQxJob

.15 .02 .01 .01 5.78

**

.03

-.08

.01

.14

*

.37

-1.14

.08

2.40

*

N

ote: N= 466,

*

p<0.05,

**

p<0.01, β= Standardized

Beta Weight, SEE= Standard Error of the

The Effect of Psychological Capital on Work Engagement: Investigating the Moderating Effect of Gender and Job

539

Nevertheless, the effect of PsyCap may depend

on several demographic factors such as employee’s

gender and job type. This argument was plausible as

the PsyCap construct was developed using pre-

existing Psychological Construct (Lorenz et al.,

2016; Youssef-Morgan and Luthans, 2015; Görgens-

Ekermans and Herbert, 2013). Consequently, the

composite score of PsyCap or the total PsyCap

hypothetically also contained similar moderating

effect with its dimensions (e.g., self-efficacy). As

mentioned earlier, most of the PsyCap dimensions

varied across genders and job type. Therefore, this

study intended to further examine any interaction

effect of gender/job with the PsyCap as composite

scores.

The results supported all hypotheses confirming

that PsyCap had a significant positive effect on

Work-Engagement and employee’s gender and job

type played important roles in the magnitude of their

PsyCap. This fact further causes interactions

between gender, job, and PsyCap. To illustrate, one

employee could have higher (or lower) effect of

PsyCap on Work-Engagement as a consequence of

his/her gender or job. PsyCap is treated as the

antecedent of many positive desired organizational

outcomes. Thus demographic aspects should be

considered with cautions. Some employees could

suffer from lower PsyCap than their co-workers due

to having unfortunate demographic factors.

The findings in this study also supported the

previous literature. According to the JDR theory,

personal resources and job resources influence

work-engagement depending on job demand or

employees’ perception towards workload (Bakker

and Demerouti, 2008; Leiter and Bakker, 2010).

This theory was in-line with several studies where

researchers found some variations in the effect of

PsyCap on employees’ outcomes such as the effect

of PsyCap among nurses (Bradbury-Jones, 2015)

and police officers (Siu, Cheung and Lui, 2014). On

the other hand, female employees also experience

more physical work demand than their male

counterparts (Aittomäki et al., 2005) causing

interaction between PsyCap and gender.

This study was very convincing that researchers

and practitioners should carefully interpret the effect

of PsyCap on Work-Engagement or other positive

employees’ outcomes. Some employees in different

industries may experience higher PsyCap than others

throughout their day-to-day work life. However, this

study was unable to detect the antecedents which

may cause the fluctuation of the employees’ PsyCap.

Another limitation, this study only compared two

job types from two distinct industries (i.e., nurses

and transport service personnel). There could be

different interactions between PsyCap, and other

variables or PsyCap could be moderated by other

variables. Having considered those limitations, this

study suggested that future investigations should

empirically test the antecedents of PsyCap, other

demographic variables related to PsyCap, and

examine the effect of PsyCap on Work-Engagement

using an experimental design.

This study has concluded that the effect of

PsyCap on Work-Engagement was moderated by

gender and job. However, it requires further

investigation to find more moderating variables, if

any. Hence, this study only examined the effect of

PsyCap on one outcome variable. The results could

be different if this study included other PsyCap-

related variables such as Organizational Citizenship

Behavior (OCB) or other undesired negative

outcomes. Therefore, future study should

incorporate more variables and examine different

mediating and moderating effects in the

relationships.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The effect of PsyCap on many positive

organizational behaviors and attitudes is ubiquitous

and easily found in any business, psychology, and

management journals. However, it is also important

to understand the effect as some demographic

variables potentially interact with PsyCap causing

moderating effect between PsyCap and its outcome

variables. This study found that PsyCap consistently

predicted Work-Engagement while controlling for

the effect of age, tenure, and education.

Furthermore, the effect of PsyCap on Work-

Engagement was moderated by employee’s gender

and job type. Employee’s gender and job should be

taken as important variables in understanding the

effect of PsyCap on employee’s outcomes.

REFERENCES

Aittomäki, A., Lahelma, E., Roos, E., Leino-Arjas, P. and

Martikainen, P., 2005. Gender differences in the

association of age with physical workload and

functioning. Occupational and Environmental

Medicine, 62(2), pp.95–100.

Antunes, A.C., Caetano, A. and Pina e Cunha, M., 2017.

Reliability and Construct Validity of the Portuguese

Version of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire.

Psychological Reports, 120(3), pp.520–536.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

540

Avey, J.B., Reichard, R.J., Luthans, F. and Mhatre, K.H.,

2011. Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Positive

Psychological Capital on Employee Attitudes,

Behaviors, and Performance. Human Resource

Development Quarterly, 22(2), pp.127–152.

Azanza, G., Moriano, J.A. and Molero, F., 2013.

Authentic leadership and organizational culture as

drivers of employees’ job satisfaction. Revista de

Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 29(2),

pp.45–50.

Bakker, A.B. and Demerouti, E., 2008. Towards a model

of work engagement. Career Development

International, 13(3), pp.209–223.

Bakker, A.B., 2010. Work Engagement. Work

Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and

Research. Psychology Press.

Bouckenooghe, D., Zafar, A. and Raja, U., 2015. How

Ethical Leadership Shapes Employees’ Job

Performance: The Mediating Roles of Goal

Congruence and Psychological Capital. Journal of

Business Ethics, 129(2), pp.251–264.

Bradbury-Jones, C., 2015. Review: Engaging new nurses:

the role of psychological capital and workplace

empowerment. Journal of Research in Nursing, 20(4),

pp.278–279.

Choi, Y. and Lee, D., 2014. Psychological capital, Big

Five traits, and employee outcomes. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 29(2), pp.122–140.

Görgens-Ekermans, G. and Herbert, M., 2013.

Psychological capital: Internal and external validity of

the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24) on

a South African sample. SA Journal of Industrial

Psychology, 39(2), pp.1–13.

Lepak, D.P. and Snell, S.A., 2002. Examining the Human

Resource Architecturew: The Relationships Among

Human Capital, Employment, and Human Resource

Configurations. Journal of Management, 28(4),

pp.517–543.

Lorenz, T., Beer, C., Pütz, J. and Heinitz, K., 2016.

Measuring psychological capital: Construction and

validation of the compound PsyCap scale (CPC-12).

PLoS ONE, 11(4), pp.1–17.

Luthans, B.C., Luthans, K.W. and Avey, J.B., 2014.

Building the Leaders of Tomorrow: The Development

of Academic Psychological Capital. Journal of

Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(2), pp.191–

199.

Luthans, F., Avey, J.B., Avolio, B.J., Norman, S.M. and

Combs, G.M., 2006. Psychological capital

development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 27(3), pp.387–393.

Luthans, F., Avey, J.B. and Lincoln, N., 2008.

Experimental Analysis of a Web-Based Training

Intervention to Develop Positive. Academy of

Management Learning & Education, 7(2), pp.209–

221.

Luthans, F., Youssef-Morgan, C.M. and Avolio, B.J.,

2015. Psychological Capital and Beyond. New York:

Oxford University Press.

MacKenzie, S.B. and Podsakoff, P.M., 2012. Common

Method Bias in Marketing: Causes, Mechanisms, and

Procedural Remedies. Journal of Retailing, 88(4),

pp.542–555.

Parthi, K. and Gupta, R., 2016. A Study of Psychological

Capital, Job Satisfaction and Organizational A Study

of Psychological Capital , Job Satisfaction and

Organizational Climate in Telecom Sector : A Gender

Perspective. Diviner, 13(1), pp.1–8.

Patton, W., Bartrum, D.E.E.A. and Creed, P.A., 2004.

Gender Differences for Optimism , Self-esteem ,

Expectations and Goals in Predicting Career Planning

and Exploration in Adolescents Understanding the

career development process across the lifespan has

been a. Internat. Jnl. for Educational and Vocational

Guidance, 4, pp.193–209.

Peterson, S.J., Luthans, F., Avolio, B.J., Walumbwa, F.O.

and Zhang, Z., 2011. Psychological Capital and

Employee Performance: A Latent Growth Modeling

Approach. Personnel Psychology, 64, pp.427–450.

Pradhan, R.K., Jena, L.K. and Bhattacharya, P., 2016.

Impact of psychological capital on organizational

citizenship behavior: Moderating role of emotional

intelligence. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1),

pp.1–16.

Rabenu, E., Yaniv, E. and Elizur, D., 2017. The

Relationship between Psychological Capital, Coping

with Stress, Well-Being, and Performance. Current

Psychology, 36(4), pp.875–887.

Reichard, R.J., Dollwet, M. and Louw-Potgieter, J., 2014.

Development of Cross-Cultural Psychological Capital

and Its Relationship With Cultural Intelligence and

Ethnocentrism. Journal of Leadership &

Organizational Studies, 21(2), pp.150–164.

Dello Russo, S. and Stoykova, P., 2015. Psychological

Capital Intervention (PCI): A Replication and

Extension. Human Resource Development Quarterly,

26(3), pp.329–347.

Schaufeli, W.B. and Bakker, A.B., 2003. UWES Utrecht

Work Engagement Scale. Occupational Health

Psychology Unit Utrecht University, (November),

pp.1–58.

Simons, J.C. and Buitendach, J.H., 2013a. Psychological

capital, work engagement and organisational

commitment amongst call centre employees in South

Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(2),

pp.1–12.

Simons, J.C. and Buitendach, J.H., 2013b. Psychological

capital, work engagement and organisational

commitment amongst call centre employees in South

Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(2),

pp.1–12.

Siu, O.L., Cheung, F. and Lui, S., 2014. Linking Positive

Emotions to Work Well-Being and Turnover Intention

The Effect of Psychological Capital on Work Engagement: Investigating the Moderating Effect of Gender and Job

541

Among Hong Kong Police Officers: The Role of

Psychological Capital. Journal of Happiness Studies.

Sun, T., Zhao, X.W., Yang, L. Bin and Fan, L.H., 2011.

The impact of psychological capital on job

embeddedness and job performance among nurses: a

structural equation approach. Journal of Advanced

Nursing, 68(1), pp.69–79.

Thompson, K.R., Lemmon, G. and Walter, T.J., 2015a.

Employee Engagement and Positive Psychological

Capital. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), pp.185–195.

Thompson, K.R., Lemmon, G. and Walter, T.J., 2015b.

Employee Engagement and Positive Psychological

Capital. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), pp.185–195.

Vanno, V., Kaemkate, W. and Wongwanich, S., 2014.

Relationships between academic performance ,

perceived group psychological capital , and positive

psychological capital of thai undergraduate students.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116,

pp.3226–3230.

De Waal, J.J. and Pienaar, J., 2013. Towards

understanding causality between work engagement

and psychological capital. SA Journal of Industrial

Psychology, 39(2).

Youssef-Morgan, C.M. and Luthans, F., 2015.

Psychological Capital and Well-being. Stress and

Health, 31(3), pp.180–188.

Zubair, A. and Kamal, A., 2015. Aunthentic Leadership

and Creativity; Mediating Role of Work-Related Flow

and Psychological Capital. Journal of Behavioural

Sciences, 25(1), pp.150–171.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

542