The Speech Act of Request: Analysis of Students’ Interaction with

Lecturers via Media Social

Ayumi and Ike Revita

English Department, Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Andalas, Padang, Indonesia

Keywords: Education, Request, Speech Act.

Abstract: Being polite is very important since politeness is closely related to our relationship with others when

interacting. The politeness must be necessarily concerned. Otherwise, one may be labelled impolite. This

writing is aimed at describing how students construct their request to their lecturers via media social. The data

are the impolite utterances used by students when they are doing request via social media WhatsApp.

Observations, note- taking, and interviews were used in collecting data. The analysis was based on the

concept proposed by Culpeper (1996). The results of the analysis is presented narratively and descriptively

and indicates that students construct their request to their lecturers via WhatsApp using different sequences.

They are 1) 1 in 1 sequence; 2) 2 in 1 sequence; 3) 3 in 1 sequence; 4) 4 in 1 sequence and 5) multi in 1

sequence.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the primary functions of language is to

maintain the continuity of relationships between its

users (Wardhaugh, 1986). Language is analogous to

a tool with very complicated rules that regulate how

a person speaks so that his interpersonal relationships

are always maintained (Wijana, 2014). The rules that

govern language use etiquette differ from one

community to another and from one language to

another. Thus, when an interaction occurs,

misunderstandings may potentially occur due to these

differences.

A speech event that demands a good ability to

speak with appropriate etiquette is making a request.

A request is a speech in which the message contained

makes the interlocutor act according to the purpose of

the speech (Revita, 2005). In other words, the purpose

of the request is the basis for the hearer's action.

Therefore, a request can cause interlocutor to lose

face because their freedom of action is imposed on

(Brown and Levinson, 1987).

The limitations of the interlocutor in acting will

become more evident if the form of speech chosen is

not appropriate, especially when directed towards a

hearer with a different cultural background. This can

lead to conflict because in a different culture a request

may be considered normal, while other cultures value

it very highly. For example, in Minangkabau culture,

requests are considered polite if done implicitly. They

are better preceded by pre-requests, such as questions

or ending with post-requests, such as reasons. That is,

the longer the speech that precedes the core of the

request, the politer the speech is. In other cultures, the

opposite may be true, a request is expected to be

delivered explicitly without being complicated

(Gunarwan, A. 1997).

To minimize the loss of face of the hearer with a

request speech act, the right strategy is needed (Felix-

Brasdefer, 2005). The strategy can be seen in the

method used or step chosen so that the hearer captures

the intent of the request.

The interactions between students and their

lecturers are susceptible to impoliteness particularly

when the student is making a request to the lecturer.

This paper describes impoliteness in the students’

interactions with their lecturer via social media. The

data are text messages containing a request that the

students sent to the lecturers via social media

WhatsApp. The research was conducted at English

Department Andalas University.

Ayumi, . and Revita, I.

The Speech Act of Request: Analysis of Students’ Interaction with Lecturers via Media Social.

DOI: 10.5220/0008678500110015

In Improving Educational Quality Toward International Standard (ICED-QA 2018), pages 11-15

ISBN: 978-989-758-392-6

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

11

2 METHOD

Data were collected through an observational method,

note-taking and interviewing. Text messages

containing impolite request were recorded using a

screenshot. The respondents were then interviewed to

find out the reasons for their choice of language.

Pragmatics and a referential identity method were

used in conducting the analysis. The result was then

presented using formal and informal methods.

3 REQUESTS AND

IMPOLITENESS

The request is utterance in which the speaker appeals

to the hearer to do something for the benefit of the

speaker. Bach and Harnish state that a request

expresses the speaker’s desire that the hearer does

something in which the hearer takes this desired

expression as the reason to act. A request does not

contain an obligation for the hearer to fulfil the

required act like a command does. It means that a

request has the potential to be granted or rejected.

Requests are closely related to the loss of face of

both the speaker and the hearer. The speaker will lose

face if the request is rejected or denied. On the other

hand, the hearer will lose face if the strategy used in

delivering the request is unsuitable. Thus, in order for

both the speaker and hearer to save face, a specific

strategy should be employed.

Blum-Kulka and Olshtain proposes nine strategies

in making a request: (1) mood derivable, (2)

performative, (3) hedged performative, (4) obligation

statement, (5) want statement, (6) suggestive

formulae, (7) query preparatory, (8) strong hint, and

(9) mild hind (Blum-Kulka and Olshtain, 1984).

The nine strategies are also found in Bahasa

Indonesia but with more varieties. The variations

appear due to contacts that have happened to the

speakers from a different culture. In delivering a

request, the speaker will consider both the speaker

and hearer’s cultural background. It will result in a

different strategy that does not put a certain culture

above the other.

The sequence of the request is another form of

request making strategy. Revita (2007) states that

there are four sequences used in making a request.

The four sequences are:

1. 2 in 1 sequence. This sequence uses two kinds

of strategies where one of them is the intended

request itself. The request can either be before

or after the supporting utterance. Either way,

the position influences the focus of attention.

A request where the main request precedes the

support is more focused than the other way

around.

2. 3 in 1 sequence. This contains three

consecutive strategies in which the main

request can be at the beginning, middle or end

of the whole utterance.

3. 4 in 1 sequence. This uses four different

strategies to achieve one goal of the request.

4. Multi in 1 sequence. Request with multi in 1

sequence is constructed using five or more

strategies. This form of request is not

commonly found.

To communicate is related to preserving the other

person's face. When talking to others, speaker or

hearer can threaten their interlocutor's face. This

means that both speaker and hearer may cause the

other to feel embarrassed or offended. Any utterance

that makes others feel embarrassed or offended can

be categorized as impolite. Culpeper calls this as

impoliteness (Culpeper, J. 2005)

Impoliteness is an attitude which threatens

another’s face. Impoliteness is reflected in an attitude

that creates discomfort to the hearer. The discomfort

is displayed through shame, anger, hurt, or being

offended. The feeling of shame or hurt, according to

Brown and Levinson in Eelen is called a Face

Threatening Act (FTA) (Eelen, 2001).

To avoid attacking or threatening people’s face,

suitable strategies are applied in communication.

Revita state that in communicating with others, a

speaker will use specific strategies so that what is

uttered will not hurt other people’s feelings (Revita,

2013).

Culpeper distinguishes two forms of impoliteness,

inherent and mock. Inherent impoliteness is any

utterance that is explicitly designed to attack face. For

example, a command, threat, or criticism [4] [12].

The utterance ‘Kamu kira keberadaan mu

diperhitungkan?’ (Do you think your existence

counts?) is considered a criticism. This criticism is

seen as impolite because it is rude and anti-social and

not in line with the rules and norms applied in the

society. The impoliteness can visibly be identified if

it is said in order to degrade the hearer. Mock

impoliteness is superficially impolite, but the force is

not intended to attack face.

Impoliteness in communication can be avoided.

One of the ways to do that is by applying language

use rhetoric. Leech distinguishes two rhetorics, the

interpersonal and the textual rhetoric [12]. Textual

rethorics demands that when talking, one must be

clear, coherent, and relevant according to the

ICED-QA 2018 - International Conference On Education Development And Quality Assurance

12

principle of cooperation proposed by Grice (1975).

Interpersonal rhetoric urges the participants to treat

others politely and uphold the principle of modesty.

Several factors motivate linguistic form selection.

The selection is made based on (1) the social distance

between speaker and hearer, (2) the magnitude of the

difference of power and domination between them,

(3) the relative status of speech acts in the culture

concerned. In another word, the utterance must be

considered not to be face threatening [12] [13] [14]

[15].

These factors are known as context. Context is

any background knowledge shared by the participants

that surround or is associated with the condition when

the utterance is produced. Different understanding of

an utterance can be influenced by social contexts,

such as the social role and status, right and

obligations, as well as the experiences of the said

participants.

Leech [12] states that context includes these

aspects:

1. Addressers or addressees (speaker/writer or

hearer/reader) that include aspects relating to

the participants of the given utterance, such

as age, socioeconomic background, gender,

level of familiarity, and other.

2. The context of utterance: all the physical

aspects and the relevant social setting of the

utterance in question [13] [14] [16]

3. The speaker's intended goal(s) of an

utterance.

4. Utterance as a form of act or activity,

referring to a verbal utterance that relates to

acts that occur in a specific situation.

5. Utterance as a verbal act. It means that the

utterance produced is a form of the verbal act.

Impoliteness comes in many different forms.

Culpeper [9] proposes five model of impoliteness, (1)

bald on record impoliteness, (2) positive

impoliteness, (3) negative impoliteness, (4) sarcasm

or mock politeness, and (5) withhold politeness.

4 DISCUSSION

The progress of sophisticated technology brings

about the change of the way people communicate [17]

[18]. The direct way or explicit utterances have

become the preference. However, this way of saying

something does not occur holistically. Minangkabau

people, for example, tend to speak implicitly [19].

They will not directly express what they want to say

but through the process of thinking and rethinking.

One process of thinking and rethinking is in the

strategy of speech acts used. Oishi[17] states that

speech as action via utterance. In the speech act, the

action is performed via utterance [18]. Five

performances exist in the speech act. They are

assertive, expressive, declaration, expressive, and

directive [20] [21] [22].

These five performances are done via language.

As a means of communication, language plays a very

important role in human’s life [23] [24]. To express

feelings, to inform, or to direct are some of the

common functions of the use of language [13].

One common function of language is directive.

Directive means the utterance is used to direct

someone else [25]. The directive impinges on the

others’ face [22]. Thus, a directive has great

possibility to be regarded impolite if it is not correctly

done [26]. This is what is generally found in

interactions via social media. Impoliteness is more

common in the utterances the students use to

communicate with their lecturers.

Typing message in social media via android or

gadget results in these students disobeying the rules

of polite communication. For example, when they

make requests of the lecturers. There are at least four

strategies used by students to their lecturers in

requesting, some of which are regarded as impolite in

Minangkabau culture.

1)

Bu, saya mau bertemu Ibu hari ini. Pukul

berapa ibu bisa?

‘I want to see you today, Mam. When can I

see you?’

2)

Bapak ke kampus hari ini? Saya boleh

bimbingan tidak?

‘Are you going to campus today, Sir. Can I

be supervised?’

Undergraduate students delivered the above two

requests to the lecturers via WhatsApp. The students

wanted to see the lecturers for thesis supervising.

They used two utterances comprising information Bu,

saya mau bertemu Ibu hari ini and question Pukul

berapa ibu bisa? Both information and questions are

intended as a request. The main idea is available at

the first utterance Saya mau bertemu Ibu hari ini.

This is also similar with 2 in which the student

gives two questions—1) Bapak ke kampus hari ini?

And 2) Saya boleh bimbingan tidak? The two

questions intended as a request.

Both 1 and 2 are regarded impolite since there is

no introduction preceding the utterance or closing or

other statements to end. This strategy is categorized

The Speech Act of Request: Analysis of Students’ Interaction with Lecturers via Media Social

13

as 2 in 1 in [27] [28] the sense that to deliver the

request, the speakers use two kinds of speech act.

The 2 in 1 strategy is one of four strategies [26]

used when making requests via social media. There

are three others ordered in frequency of occurrence--

3 in 1, 4 in 1, multi in 1, and 1 in 1. The 1 in 1 strategy

is categorized very impolite because the students

directly make the request to the lecturers. For

example, is as displayed in 3.

3)

Bu, saya mau bimbingan dengan ibu hari ini.

‘I want to be supervised by you today, Mam.‘

The utterance 3 is directly and explicitly stated. His

request to be supervised by the lecturer is delivered

by using a literal request [25]. No supporting

utterances are preceding or following the request.

Such kind of request is regarded impolite because of

the length, the strategy, the directness, and the choice

of words [29]. Such a strategy is sometimes used by

students who are not aware that they are

communicating with their lecturers. Furthermore, this

strategy needs to be avoided when addressed to one

older than the speaker in the Minangkabau culture--

the culture of both speakers and hearers-- people who

share a set of rules of speaking [25] .

Kato nan ampek ‘the four words’ has kato

mandaki ‘up grading’, kato manurun ‘down grading’,

kato mandata ‘horizontal’, and kato malereang

‘sloping’. These four words consider mostly the age

of the hearers but the relationship and the power

among participants also play a role [26] [30]. Those

who fail to implement kato nan ampek in

Minangkabau context are regarded not only impolite

but also disrespectful [31].

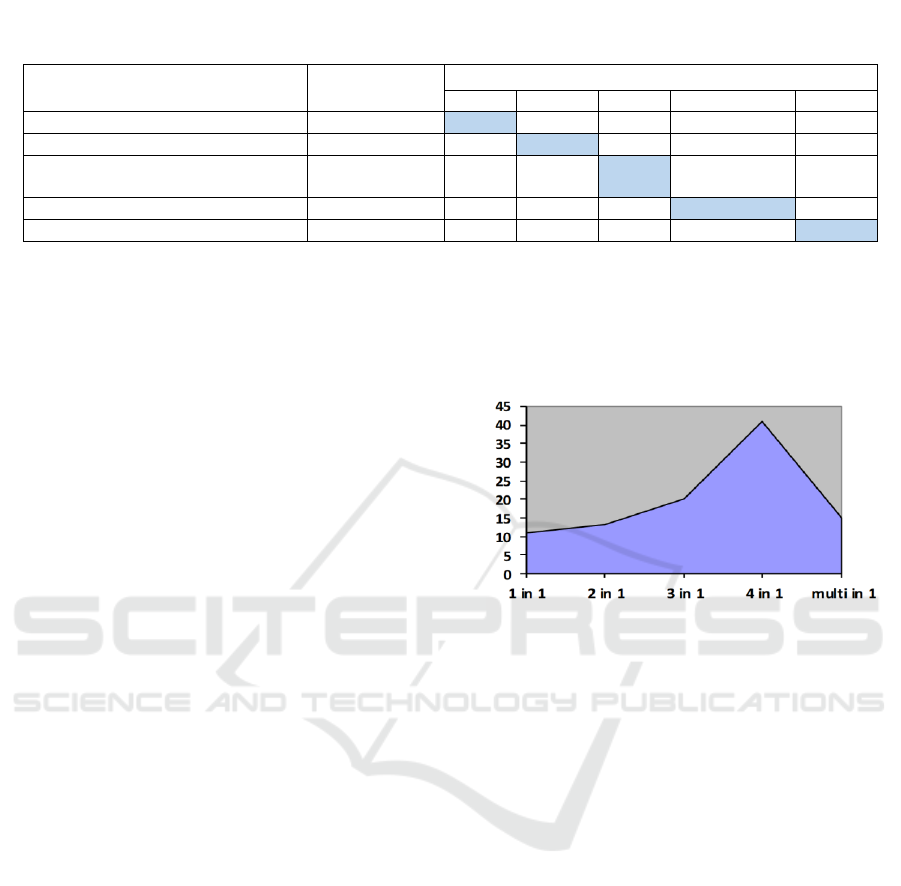

The occurrence of the strategies in requesting via

media social from students to lecturers can be seen in

table 1.

It clearly seen that the use of 4 in 1 strategy is most

commonly used, followed by 2 in 1, 3 in 1, 2 in 1, and

1 in 1. Among these four, the multi in 1 is regarded

the politest because it is the longest. The longest the

utterance, the more polite it will be [3][14]. The use

of 2 in 1 and 1 in 1 is due to the lack of knowledge of

how to communicate with an older interlocutor [16]

and the character of students which ignore the aspect

of politeness.

The depiction of the occurrence of the strategy in

percentage is shown on fig 1 below.

Figure 1: The Occurrence of Strategy of Request from

Students to Lecturers via Media Social

5 CONCLUSIONS

As students who interact with their lectures in daily

basis, the strategies used by the undergraduate

students in making and delivering their requests to

their lectures who are older than them many could be

considered impolite. The occurrences of multi in 1

sequence are very low compare to the other strategies.

This may be caused by the lack of knowledge of how

to communicate the right way according to the norm

and culture of Minangkabau. Education on Kato nan

ampek to students in Minangkabau should be given

more in schools so that they know how to interact

with people older than them politely and respectfully.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Huge thankful to Rector of Universitas Andalas and

Dean of Faculty of Humanities, for funding the

research. The Lecturers and Students around

Universitas Andalas, and the respondents thank you

for the kindness and cooperation in providing data.

Table 1: The occurrence of strategies in speech of request from students to lectures via media social.

Data Number

Total Number

Strategy

2 in 1

3 in 1

4 in 1

Multi in 1

1 in 1

1, 3, 39, 24, 40, 42,

6

2, 4, 5, 7, 10, 26, 28, 35, 36,

9

6, 8, 9, 12, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 27,

29, 30, 31, 34, 35, 37, 38

19

11, 17, 22, 26, 28, 32, 33

7

14, 18, 23, 25, 41

5

ICED-QA 2018 - International Conference On Education Development And Quality Assurance

14

REFERENCES

Blum-Kulka S. and E. Olshtain. 1984. “Request and

Apologies: A Cross Cultural Studiey of Speech Act

Realization Patterns (CCSARP),” Applied Linguistics,

no. Volume 5, pp. 196-213, 1 October.

Brown, P. and S. C. Levinson. 1987. “Universals in

Language Usage: Politeness Phenomena,” Questions

and Politeness, p. 129.

Cahyono, B. Y. 1998. Kristal-kristal Ilmu Bahasa.

Surabaya: Airlangga University Press.

Crystal, D. 2001. Language and the Internet, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Culpeper, J. 2005. Linguistic Impoliteness: Using

Language to Cause Offence. UK: Lancester Universit.

Dörnyei, Z., and P. Skehan. 2003. “Individual Differences

in Second Language Learning,” dalam The handbook of

second language acquisition, M. Long dan C. Doughty,

Penyunt., Malden, Blackwell P.

Eelen, G. 2001. Kritik Teori Kesantunan. Surabaya:

Airlangga University Press.

Felix-Brasdefer, J. C. 2005. “Indirectness and politeness in

Mexican requests,” dalam Selected Proceedings of the

7th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium, Somerville, MA.

Gunarwan, A. 1997. “Tindak Tutur Melarang di dalam

Bahasa Indonesia di Kalangan Penutur Jati Bahasa

Jawa,” Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia, no. 15.

Leech, G. 1983. Principle of Pragmatics. New York:

Longman.

Oishi, E. 2006. “Austin’s Speech Act Theory and the

Speech Situation,” Eser. Filos, p. 1–14.

Oktavianus, and I. Revita. 2013. Kesantunan Berbahasa.

Padang: Minangkabau Press.

Navies, A. Pemikiran Minangkabau Catatan Budaya A.A

Navies. Bandung: Angkasa.

Poedjosoedarmo, S. 1979. Tingkat Tutur dalam Bahasa

Jawa. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan

Bahasa Depdikbud.

Poedjosoedarmo, S. 2001. Filsafat Bahasa. Surakarta:

Muhamaddiyah University Press.

Revita, I. 2005. Tindak Tutur Permintaan dalam Bahasa

Minangkabau.

Revita, I. 2007. “Strategi Permintaan dalam Bahasa

Indoenesia (Kajian Lintas Budaya),” dalam Seminar

Internasional Austronesia, Bali.

Revita, I. 2010. “Konstruksi Tuturan Permintaan dalam

Komunikasi via SMS,” dalam Seminar Internasional,

Padang.

Revita, I. 2010. “Tindak Tutur Mahasiswa Kepada Dosen,”

dalam Seminar Internasional Multidisciplined

Linguistics, Padang

Revita, I. 2013. Pragmatik: Kajian Tindak Tutur

Permintaan Lintas Bahasa. Padang: FIB.

Revita, I., R. Trioclarise and N. Anggreiny. 2017.

“Politeness Strategies of The Panders in Women

Trafficking,” Bul. Al-Turas, no. XXIII(1), p. 191–210.

Revita, I. 2017. “Women Trafficking dalam Bingkai

Sosiopragmatik,” Visigraf, Padang.

Revita, I. S. Wekke, and R. Trioclarise. 2017 “Empowering

the Values of Minangkabau Local Wisdom in

Preventing the Activity of Women Trafficking in West

Sumatera,” p. 3–6.

Revita, I. 2018. Kaleidoskop Linguistik. Padang: CV.

Rumahkayu Pustaka Utama.

Schneider, K. 2012. Pragmatics of Discourse. Berlin: De

Gruyter Mouton.

Searle, J. R. 1979. Studies in the theory of speech acts.

Searle, J., F. Kiefer, and M. Bierwisch. 1980. Speech act

theory and pragmatics, Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Wardhaugh, R. 1986. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics.

Oxford: Basil Blackwel.

Walters, J. 2005. Bilingualism. New Jersey: Lawrence

Erlbauam Associates Publishers.

Wijana, I. G. P. “Teori Kesantunan dan Humor,” in Seminar

Nasional Semantik, Universitas Sebelas Maret, 2004.

Yule, G. 2006. The Study of Language. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

The Speech Act of Request: Analysis of Students’ Interaction with Lecturers via Media Social

15