Urban Parks as a Part of Urban Design Implementation towards

Healthy Cities: What Can Be Achieved through the WHOs Healthy

Cities Model?

Faruq Ibnul Haqi

1

, Parmo

1

, and Arfiani Syariah

1

1

Department of Architecture, Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Ampel Surabaya

Keywords: Green Open Spaces, Urban Parks, Urban Design, and Healthy Cities.

Abstract: Rapid urban growth and massive urbanization are continuing occurrence in most of the cities around the

world. In 2008, more than half of the global population were living in urban areas and was predicted will be

increased to 70 per cent in 2050 (UN-Habitat 2009, p.8). Indonesia as one of the biggest countries in Asia

also contributes to this rapidly changing. This condition has created numerous environmental consequences

due to high demand for space that is not aligned with the carrying capacity of place. This paper aims to review

evidence related to the extent of implementing urban parks which can play a partial role in applying urban

design in the direction of healthy cities. The method adopted to address the objective of the paper is content

analysis. Content analysis is based on the academic and professional literature, with a focus on the open space,

urban parks, healthy cities, urban planning and design fields. The paper concludes that regardless of some

contradictory evidence, many studies have confirmed that good urban design can be achieved and one of

which is through the application of attractive urban parks by providing various supporting facilities to

encourage physical activity for people. As such, it could help improve the built environment of

neighbourhoods in relation to healthy cities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most cities around the world still continue to

experience massive urbanization and rapid urban

growth, not least in developing countries such as

Indonesia. In line with UN-Habitat (2009, p.8) more

than half of the global population was forecast will be

increased in 2050 to 70% and were living in urban

areas. Indonesia is one of the largest countries in Asia

which also has contributed to this rapid changing.

This condition has created numerous environmental

consequences due to high demand for space that is not

aligned with the carrying capacity of place.

Moreover, urban health problems that are very

complex as a result the issues that has been mentioned

above, in which the matter has been influenced by

several aspects, ranging from social, economic, and

environmental. In line with WHO (2010),

environmental pollution; inadequate health services;

homelessness; traffic congestion; disease such as

HIV/AIDS, narcotics use and urban poverty; slum

areas up to social and economic problems such as

street children and singers; are a number or urban

concerns that occur not only in developing countries

likely Indonesia but also in developed countries

including Europe countries and Australia. Putting this

into consideration, Healthy City that promotes heathy

living for people, develops indicators in

environmental dimension where principles of urban

design play a significant role.

Healthy City is a broad program which aims to

provide an environment for healthy, convenient, and

safe living. To achieve these outcomes,

implementation of design features into the life of the

community needs to be done in cooperation with the

local government as a facilitator and instructor. As

presented by de Leeuw (2009), the healthy city

program entails integrating and empowering

communities and services via city forums which are

facilitated by the government. These forums have a

role to determine clear directions and priorities for

regional development planning that integrate various

aspects of life, so that the region can achieve a healthy

and comfortable city for residents to live.

Such a program requires a thorough

understanding of the various parties, the community,

68

Haqi, F., Parmo, . and Syariah, A.

Urban Parks as a Part of Urban Design Implementation towards Healthy Cities: What Can Be Achieved through the WHOs Healthy Cities Model?.

DOI: 10.5220/0008908400002481

In Proceedings of the Built Environment, Science and Technology International Conference (BEST ICON 2018), pages 68-75

ISBN: 978-989-758-414-5

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

stakeholders and government on the importance of

the impact of development on health, then positioning

the health aspects of the planning policy as a priority

in each region, across sectors and communities. This

is an effort to promote the importance of health in

people's lives. In connection with this, the concept of

a healthy city is one of the programs that have been

successfully applied in various cities around the

world to anticipate urban health issues.

This paper will discuss studies related to the role

of urban parks as a part of urban design towards

healthy cities. First, it describes the healthy city

conception and its indicators that related to urban

parks and open space provision, then discusses the

benefits of urban parks and open space in health

aspects follows by aspects influence the use of urban

parks and open space.

2 METHODS

The method adopted to address the objective of the

paper is content analysis. Content analysis is based on

the academic and professional literature, with a focus

on the open space, urban parks, healthy cities, urban

planning and design fields. In line with the WHO

(2010), the healthy city program has been running for

more than 20 years, and it has undergone evaluation

for the improvement and advancement of a healthy

city member. Following this evaluation, several

documents have been published that provide a

complete picture of what is necessary to create a

healthy city (WHO 2014).

Then this was structured into specific areas in an

effort to explain the multitude of research studies to

present that related to urban design in the direction of

healthy city. At the outset, it describes the concept of

healthy city and its implementation methods that

associated to urban design elements. Then review the

WHO model for healthy city and lastly describes

healthy city in Indonesia.

3 DISCUSSIONS

3.1 Healthy City

Healthy city, that emerged in 1986 and was initiated

by World Health Organization (WHO), has long

historical background. Originally, it was motivated

by urban healthy issues such as poor sanitation,

pollution, crowding, slums and epidemic infectious

disease experienced by industrial cities in the late

19th century (Ashton 1992, p. 1). Along with its

development, the scope of public health became

wider and shifted from sanitary ideas into ecological

consideration. This refinement has implications on

the way we living in urban areas and policies

underpin it (Ashton 1992, p. 7). World Health

Assembly in 1997 developed Health For All

strategies that implemented in local, national and

international levels (WHO Regional Office for

Europe 1997, p.5).

Healthy city movement tries to encompass whole

aspects of healthy living. This is reflected from its

definition and its objectives. According to WHO

(1998, p.13), healthy city refers to:

‘One that is continually creating and

improving those physical and social

environments and expanding those

community resources which enable people to

mutually support each other in performing

all the functions of life and in developing to

their maximum potential’.

This idea accommodates city or community

vision on health into strategic plan that includes

social, environmental, economic, political and

technological environments (Hancock 1992, p 28;

and Haqi et al 2018). The Healthy City objectives are

to create a health-supportive environment, to achieve

a good quality of life, to provide basic sanitation &

hygiene needs, and to supply access to health care

(WHO 2014).

Well-defined determination of health and aspects

that influence it in order to achieve healthy city goals

and advantage an effective action is essential. The

WHO European Healthy Cities Network developed

53 indicators gained from working group in local

level to determine health dimension in cities. After its

early implementation, these indicators revised by

excluding unreliable measurements and produced 32

indicators that are used until recent day (Healthy

Cities Taipei 2010). Webster & Sanderson (2012)

evaluate the 32 Healthy City Indicators (HCIs) and

argue that current 32 indicators not provide a holistic

approach in assessing health in city (p.S60). Each city

has unique circumstances and indicators to measure

and to evaluate health should be based on local

perceptions (Taher & Haqi 2017; Hancock 1992,

p.23; Werna & Harpham p.633).

HCIs are divided into four main categories which

are health indicators, health and service indicators,

environmental indicators and socio-economic

indicators. Among these categories, environmental

indicators directly connect with physical quality of

Urban Parks as a Part of Urban Design Implementation towards Healthy Cities: What Can Be Achieved through the WHOs Healthy Cities

Model?

69

cities. It includes air pollution, water quality, sewage

system, household waste, green space, derelict

industrial sites, sport and leisure, pedestrian, cycling,

public transport and living space (Healthy Cities

Taipei 2010).

Based on HCIs, the role of parks and open space in

achieving healthy city is substantial since almost half

of environmental indicators rely on parks and open

space availability. According to Healthy Space and

Places (2009), parks and open space means a reserve

of land for sport, leisure, natural preservation, green

space provision and/or storm water management

purposes. In this sense, greenery or green open space

includes as a part of open space. Based on this

definition, parks and open space encompass various

activities that give benefits for communities.

3.1.1 Health Benefits of Urban Parks

Parks and open space contribute to enhance a healthy

environment particularly in urban areas. It contributes

to mental healing process. Grahn & Stigsdotter (2010)

found that green open space might attribute to stress

healing through eight dimensions which were:

experience of nature, contact with open area with a

view or prospect, sense of silent and calm surrounding

or serene, experience of spacious, rich in species,

experience an enclosed and safe environment or

refuge, human culture, and social activity. Social and

culture were less preferred for people who under stress.

The authors interpret that creating an area with nature

and refuge dimensions would be more favoured for

individual experiencing stress (pp. 270-272).

Parks and open space are places for physical activity

such as walking, running and cycling which directly

give impact on human health (Kaczynski, Potwarka &

Saelens 2008; Cohen et al. 2007; Schipperijn et al.

2010). Study in Dutch urban parks by Chiesura (2004)

concludes that urban natural environment has many

social and psychological benefits for citizens such as

place for relaxation, escape from daily routine, express

positive feeling like freedom, unity with nature and

happiness (p. 137). Green open space contributes to

enhance public health by reducing side effect of car

dependency. Combination of vegetation in green space

areas was effective to reduce the noise more than

12.25% and to decrease air temperatures up to 8.18% in

Waru-Sidoarjo highway (Pudjowati et al. (2013, pp.

463-465).

3.1.2 Factors Influence the Use of Parks and

Open Space

Many factors such as gender, motivation, age,

socioeconomic and demographic of population

influence the extent of health perceived among

citizens. Study conducted by Cohen et al. (2007) at

City of Los Angeles found that males used public

parks more than female and they were two times

become vigorously active (p. 512). In motivation

factor, the most common reason to visit parks is

enjoying the weather and getting fresh air

(Schipperijn et al. 2010, p.135). The motivation and

activity in using parks were varied among age-

groups. Thus, all target groups should be considered

in recreational requirements (Chiesura 2004, p.137).

Haqi (2016) and Gehl & Gemzoe (2003) further

suggests that public spaces and green spaces should

include in sustainability indicators with parameters

such as satisfaction and perception of residences.

Maas et al. (2006) found that there were positive

relationship between quantity of green space and

perceived general health. Young, elderly and

secondary educated people tend to gain more benefits

of the presence of parks in their surrounding

environment rather than other groups in large cities

(p.591). Mitchell & Popham, (2007) found that higher

provision of green areas was related to better public

health and was varied among combination of income

and urbanity. However, for higher income suburban

and higher income rural areas, there was no

significant correlation. Worse health perceived was

found in low income areas with higher proportion of

green space. This might be caused by the poor

maintenance of green space.

Physical factors like distance, size, and facilities

also contribute to the preference of people visit parks

and open space. Residents who lived within a mile of

parks were four times more likely to visit the parks

once a week compare with those living further away

(Cohen et al. 2007, p. 513). Schipperijn et al. (2010)

found that people who lived within 300m from green

space tend to visit the parks at least once a week (p.

135). Giles-Corti et al. (2005) found that higher level

of walking was encouraged by attractive large size of

public open space as well as close proximity distance

to access it. This study also found that park size

impact on higher walking levels was equivocal

because users tend to use public open space with

attributes such lighting, adjacent ocean or river,

present of water feature and present of birdlife even

if in small size of parks (pp. 173-174). Kaczynski,

Potwarka and Saelens (2008) found that parks with

attributes more attractive for physical activity while

size and distance had limit influence. Facilities

provides in the parks were more important for visitors

rather than parks amenities. They suggest that park

planning that consider the provision of attractive

features might encourage physical activity (p. 1454).

BEST ICON 2018 - Built Environment, Science and Technology International Conference 2018

70

People in each place has its own uniqueness in

perceiving parks and open space. Several investigators

Ibnul Haqi and Pieters (2019), Hakim (2007), and

Pudjowati et al. (2013) who have conducted studies on

the urban context in Asia. They conclude that people

who lived in varied neighbourhoods have varies

preferences for open spaces. These variations were

based on local ecology and local government finances,

level of management and maintenance, and control of

issues related open spaces utilization. People in all

three cities were perceived open space as recreation

venues, religious places, social and political

celebration (p161-162). The uniqueness of each

neighbourhoods found in this study leads to the

meaningful contribution to open space planning and

design which should consider local culture, climate,

social values and people’s needs.

Achieving health environment by the utilization

of parks and open space involves many

considerations, not only in physical aspects but also

in social and cultural contexts. Gender, motivation,

age, socioeconomic and demographic of population

as well as physical factors like distance, size, and

facilities, influence the perception and preference of

people to visit parks and open space. Local culture,

social values, climate and people’s need that varied

from one place to others also give significant

contribution. Taking these factors into consideration

in planning and designing process might generate a

better health environment.

3.2 Urban Design and Health

There are many and varied definitions of “urban

design” for example Schurch (1999), Carmona (2010)

and Rowley (1994). This research will adopt the

definition of urban design by Kozlowski (2006).

'Urban design is multifaceted discipline

dealing with a range of social, economic,

transport, infrastructure and cultural

aspects that have an ongoing impact on the

functioning and form of the urban

environment'.

Urban design principles have the potential to

deliver high level strategic direction to guide the future

development of towns and cities. When planners think

about urban design, they design and build the

communities that can affect human physical and

mental health (Liptay 2009). It is also supported by

Day (2003), who states that urban design and planning

elements are something that is very considered in

forming an urban settlement which put more emphasis

on sustainable environment, a sense of community, and

the identity of a place. Academics and researchers in

the field of urban planning have been recognising that

urban form can affect public health, environmental

condition, and social wellbeing. There is a lot of work

to be done by the leaders of the city to reduce these

issues, so required a cross-sector collaboration toward

the goal for a healthy city. The question arises why

urban design can improve of population health, and

what is great from these principles so it can achieve a

healthy city predicate?

Urban design be able to considerably affect the

environmental, economic, health, social and cultural

results of a place:

Physical scale (building and natural form), space,

and the atmosphere of the place is largely

determined by urban design. Therefore, it has

influenced the balance of natural ecosystems and

built environments, and their sustainability

outcomes.

The socio-economic composition and the

economic success of a region are determined by

successful of urban design. The successful of urban

design has encouraged people to do business and

local entrepreneurship in their region.

Urban design can influence health and the social

and cultural impacts of a locality: how they use a

place, how they move around, and how people

interact with each other.

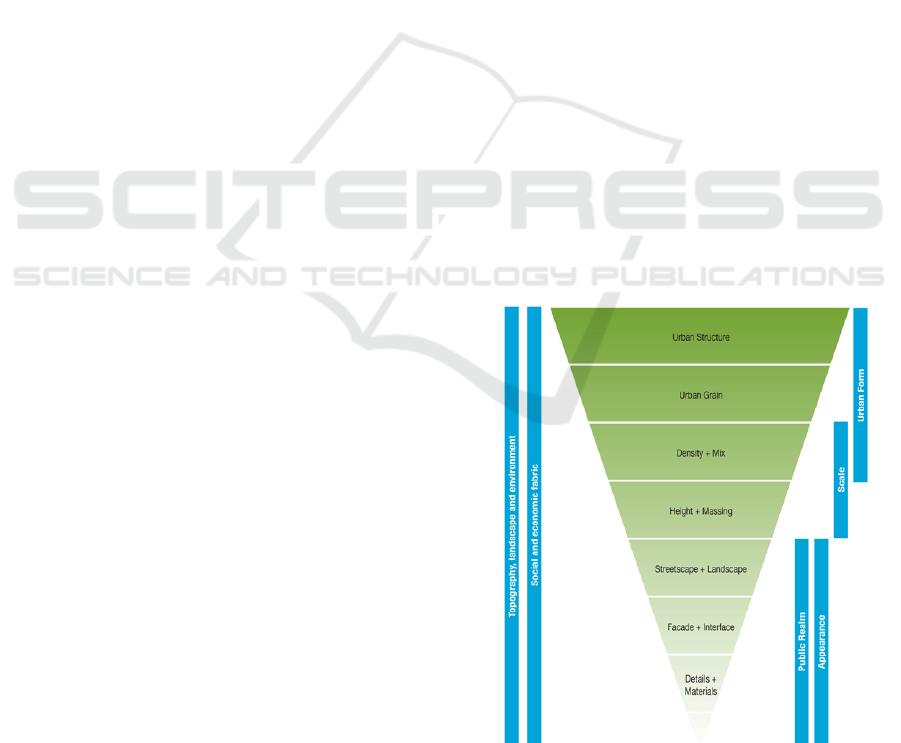

Figure 1 shows the approximate hierarchical

relationship between the elements of urban design

Source: Adopted from urbandesign.org.au

Figure 1: Elements of urban.

Urban Parks as a Part of Urban Design Implementation towards Healthy Cities: What Can Be Achieved through the WHOs Healthy Cities

Model?

71

The built environment encompasses a range of

physical and social elements that may probably

influence healthy city and make up the structure of a

community (Northridge, Sclar & Biswas 2003). One

of the central goals in public health is creating healthy

living. The connection between the health and

physical environment that has long been recognised

but it has been inadequately addressed. Hence, urban

design approach delivers general context to guide

government initiatives in planning, policy

development, infrastructure provision, creating a

liveable neighbourhood and private development. It

addresses long term planning focus, vision and

character of the place, land use structure, improves

permeability and legibility of the place and fosters

people for doing physical activities. Urban design is

concerned with both the structure of the cities and the

function of the cities. There are many urban design

principles which help to improve the built

environment and encourage physical activities. Some

of the urban design principles are identified to

improve the built environment and encourage

physical activities, such as:

Permeability / access

According to Schiller and Evans (2006)

permeability promotes the connection within the

spaces as well as linking to environs with more than

one route. In order to encourage people for cycling and

walking, the street layouts are really essential, streets

and paths which connect to multiple destinations.

Vitality

Through open space and public realm, this

principle encourages people to participate in the

social activities. This will allow social interaction for

everyone in different ages and backgrounds, allows

intensity of activity, and will build ups the social

capital. In order to obtain the vitality, Schiller and

Evans (2006) emphasise that design need to have

diverse activities throughout the day to attract people.

Legibility

Good legibility encourages people to walk and to

do physical activities as related to good streetscape.

To make built environment legible, there is need to

consider following design elements, for example as

stated by Schiller and Evans (2006, p. 3) "clear street

pattern and urban structure, with elements to aid the

recognition of uses and orient movement".

Richness

According to Schiller and Evans (2006) richness

refers to the capacity of the layout pattern to

accommodate complementary urban activities with

mix uses. In order to encourage people to walk and

ride, normally the mix land use offers commercial and

social activities within walking distance. It is also

supported by Gehl (1987), he stated that there is a

strong relationship between walk and ride as a part of

physical activity and the quality of public realm.

Open Space

Utilization of open space that accessible for many

people have been encouraging them to participate in

community activities. Community activity and social

inclusion will help to reduce the risk of the urban

health since it will encourage the physical activity.

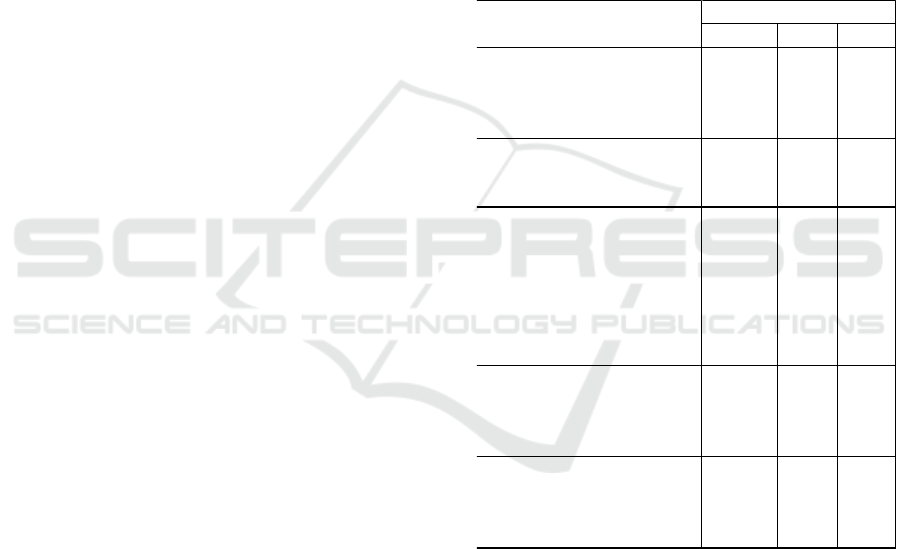

Table 1: Design Principles to encourage physical activities.

Source: Montgomery 1998; Bentley et al., 1985, and

Schiller and Evans, 2006.

Moving onto urban health, the initial notion of

healthy city has been introduced by the World Health

Organisation (WHO) around the period of 1987-1992

in Europe as a pilot project to response a variety of

urban health issues. Urban health problems are very

complex and affected by many factors, ranging from

social and economic to environment and living

conditions. The need for refinement has implications

on the way we living in urban areas and policies

underpin it (Ashton 1992, p. 7). Along with its

improvement, the range of urban health turn out to be

The Principles of Urban Design

E

n

co

u

r

a

g

e

P

h

ysic

a

l

A

ctiviti

e

s

Wal

k

i

n

g Cycling Ex

e

r

cis

e

P

e

r

meabilit

y

/

A

ccess

Pedestrian friendly

Layout pattern with alternative

Legible Street and road layout

V

italit

y

Constant activity throughout the day

Diversity of activity

L

egibilit

y

Good accessibility

Location of public space

Access to social infrastructure and open

space

Good streetscape

Massing and scale of the building

R

ichness

Mix land use

Quality of pedestrian walkways

Housing diversity and choice

O

pen Spa

c

e

Activity

Location

Safety

BEST ICON 2018 - Built Environment, Science and Technology International Conference 2018

72

varied and altered from sanitary ideas into ecological

consideration. World Health Assembly in 1997

developed health for all strategies that implemented

not only in international levels but also in local and

national (WHO Regional Office for Europe 1997,

p.5). The idea of a healthy city is determined by

equitable access to basic prerequisites for health: a

safe physical environment, easy access to

transportation, adequate resources, clean water and

air, food, education, income, social supports. The

WHO defines a healthy city as:

‐ A high quality of physical environment which

clean and safe

‐ Ease of access by the public to a variety of

experiences, resources with the chance for a wide

variety of interaction, communication and contact

‐ An environment that is sustainable at the present

and sustainable in the long term future

‐ A community of mutual support and strong

The WHO has been central to the development of

the Healthy City concept and to its promotion both in

the west and the east. Healthy city program tries to

cover whole qualities of healthy living. This is

indicated from its objectives and its definition which

in line with WHO (1998, p.13).

As it is known that the World Health Organisation

(WHO) has been a main development of the healthy

city and has a clear concept of healthy cities (WHO

2010). During its development, the European

countries have introduced the initial WHO healthy

city projects around the period 1987-1992, as a result

the definition of a healthy city was completed.

“The concept of a healthy city is one that

offers us an interesting new perspective on

the city and an exciting opportunity to

enhance health and well-being. We believe

that the city is the vital center of our

industrialized civilization, that health is a

result of the complex interactions of people

with each other and their physical and social

environments and that the city has a crucial

role to play in the health and survival of

humanity” (Ashton, Grey & Barnard 1986)

The essential within the definition of a healthy

city is that a 'healthy city' is one program that is

continuously kept trying to improve public health

(WHO 1986). As such, in order to enhance control

over people health, enabling them to do the planning,

implement of the concept and principles of health

promotion at the community level. The fundamental

to the Healthy Cities approach is achieving the

integration of activities and city programs. The

effectiveness of efforts to improve urban health can

be achieved if the program and integration in the

region run successfully. This is because cooperation

and coordination among the parties involved in

accordance with the track and make it efficient. In

terms of resources sharing, integration will lead to

substantial benefits, synergy between activities, and

cost-effective solutions. Key players whose efforts

may need to be coordinated in a Healthy Cities project

such as local, provincial/state and national politicians;

government service providers from a variety of

sectors; nongovernmental organizations; local,

provincial and national government authorities; and

community members.

According to Dannenberg, Jackson, et al (2003),

health policies related to urban planning include

urban form factors; network street connectivity, land

use mix and density, site design, and street design can

play a substantial part in shaping the health and well-

being of the residents of the community. Cities should

also become greener for humans who inhabit them

and for the sake of many species, and as a model for

future cities (Ritchie et al 2013).

3.3 The WHO Model’s Healthy City

A healthy city commits to a process of trying to attain

social environments and better physical. Any city can

start the process of becoming a healthy city if it is

committed to the development and maintenance of

physical and social environments which support and

promote better health and quality of life for residents.

Building health considerations into urban

development and management is crucial for healthy

city. The movement of healthy city model in several

countries both developed and developing countries

demonstrates that there are significant variations in

the implementation of a healthy city that conducted in

each region. These differences have reflected the

differences in local history and culture, economic,

and political development of a country.

The program conducted by healthy city models

differ significantly in countries with different levels

of development. As an example of this is in

developing countries, the development of basic urban

infrastructure, the provision of sanitation and clean

water are paramount. Different to what happens in

developed countries as the WHO model’s healthy

city, such as Japan, New Zealand and Australia, the

main concerns are protection of the environment,

crime and injury prevention (Takano 2003).

Urban Parks as a Part of Urban Design Implementation towards Healthy Cities: What Can Be Achieved through the WHOs Healthy Cities

Model?

73

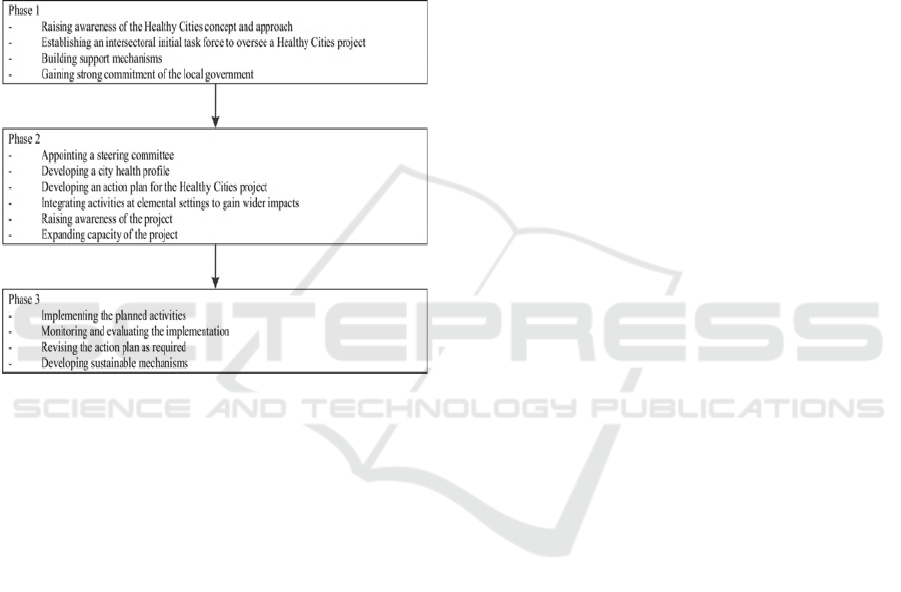

Figure 2 presents the essential e steps in the

development of a healthy city. As stated WHO (2000,

p.14), the steps in the development of a healthy city

model are divided into three phases. Phase 1 begins

with awareness raising and established the formation

of cross-sectoral task force for a healthy city and will

eventually gaining a firm commitment from the local

government. Phase 2 works to develop organizational

structure, working mechanisms, city health profile,

plan of action, and capacity for the model. Phase 3

implementing the action plan that has been planned

and established.

Figure 2: the steps in the development of a healthy city

model (WHO 2000).

Involving community-based organizations and

non-governmental (NGOs) from the commencement

of a healthy city development is essential. The

process needs resources and time as effective

inclusion of community interests is a developmental

process. Public participation can take place at all steps

of a healthy city development, including preparation

of a local action plan, specific activities and task

groups, establishment of a vision for the community,

needs assessment, and management of and guidance

to the overall healthy city model.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Urban parks and open space play an important role in

healthy city concept. It provides many benefits in

social and health dimensions. Achieving these

advantages needs consideration in aspects such as

gender, motivation, ages, socioeconomic and

demographic of population as well as physical factors

like distance, size, and facilities. In addition, local

culture, social values, climate and people’s need are

also important.

Based on an extensive literature discussion, urban

parks could be significantly influence urban design

implementation towards healthy cities. The built

environment encompasses a range of physical and

social elements that may probably influence healthy

city and make up the structure of a community.

Furthermore, the concept of healthy city has been

introduced by the World Health Organisation (WHO)

has the objective to response a variety of urban health

issues. Healthy city program tries to cover whole

qualities of healthy living. In addition, a healthy city

model by WHO commits to a process of trying to

attain physical and social environments which

support and promote better health and enhance

quality of life for people.

REFERENCES

Ashton, J 1992, ‘The origins of healthy cities’, in J Ashton

(ed.), Healthy cities, Open University Press,

Philadelphia, pp. 1–12.

Bentley, I, Alcock, A, Murrain, P, McGlynn, S & Smith, G

1985, Responsive environments: a manual for

designers, Oxford, Architectural Press.

Carmona, M (ed.) 2010, Public places, urban spaces: the

dimensions of urban design, Routledge.

Chiesura, A 2004, ‘Role of urban parks for the sustainable

city’, Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 68, no. 1, pp.

129–138.

Cohen, D, McKenzie, TL, Sehgal, A, Williamson, S,

Golinelli, D, & Lurie, N 2007, ‘Contribution of public

parks to physical activity’, American Journal of Public

Health, vol. 97, no. 3, pp. 509-514.

Dannenberg, AL, Jackson, RJ, Frumkin, H, Schieber, RA,

Pratt, M, Kochtitzky, C et al 2003, 'The impact of

community design and land-use choices on public

health: a scientific research agenda', American Journal

of Public Health, vol. 93, no. 9, pp. 1500-1508.

Day, K 2003, ‘New urbanism and the challenges of

designing for diversity’, Journal of Planning Education

and Research, vol 23, pp. 83-95.

De Leeuw, E 2009, 'Evidence for healthy cities: reflections

on practice, method and theory', Health Promotion

International, vol. 24 (suppl 1), pp. i19-i36).

Gehl, J 1987, Life between buildings: using public space,

Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

Gehl, J & Gemzoe, L 2003, ‘Winning back public space’,

in R Tolley (ed), Sustainable transport: planning for

walking and cycling in urban environments,

Woodhead, Cambridge, pp. 97-106.

Giles-Corti, B, Broomhall, MH, Knuiman, M, Collins, C,

Douglas, K, Ng, K, Lange, A, & Donovan, RJ 2005,

‘Increasing walking : how important is distance to,

BEST ICON 2018 - Built Environment, Science and Technology International Conference 2018

74

attractiveness, and size of public open space?’,

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 28, no.

2S2, pp. 169-176.

Grahn, P. and Stigsdotter, U.K., 2010. The relation between

perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and

stress restoration. Landscape and urban planning, 94(3-

4), pp.264-275.

Hakim, R 2007, ‘The alternative of green open space

management in Jakarta city, Indonesia’, Student PhD

paper, University of Technology Malaysia, Malaysia.

Hancock, T 1992, ‘The healthy city: utopias and realities’,

in J Ashton (ed.), Healthy cities, Open University Press,

Philadelphia, pp. 22-29.

Haqi, F. I., Izzudin, M. A., Prihatmaji, Y. P., & Munir, M.,

2018, Bambooland Social Enterprise as an Innovation

of Rural Communities towards Sustainable Economic

Creative. Retrieved from https://jakadpublisher.org/

wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Faruq-Ibnul-Haqi.pdf

Haqi, F.I., 2016. Sustainable Urban Development and

Social Sustainability in the Urban Context. EMARA

Indonesian Journal of Architecture, 2(1), pp.21-26.

Retrieved from http://emara.uinsby.ac.id/index.php/

EIJA/article/view/15

Ibnul Haqi, F., and Pieters, J., 2019, The Role of Leadership

Influencing the Health Equality Through Urban Design

in the City of Surabaya, Indonesia, International Journal

of Engineering & Technology, vol. 8, no. 1 (9), pp. 434-

438. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v8i1.9.26703

Healthy Cities Taipei 2010, WHO 32 healthy cities

indicators, Healthy Cities Taipei, viewed 8 May 2016,

http://healthycity.taipei.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=1307814

&CtNode=39516&mp=100068

Healthy Space and Places 2009, Design principle – parks

and open space, Healthy Space and Places, viewed 8

May 2016, http://www.healthyplaces.org.au/userfiles/

file/Parks%20and%20Open%20Space%20June09.pdf

Kaczynski, A.T., Potwarka, L.R. and Saelens, B.E., 2008.

Association of park size, distance, and features with

physical activity in neighborhood parks. American

Journal of Public Health, 98(8), pp.1451-1456.

Kozlowski, M., 2006. The emergence of urban design in

regional and metropolitan planning: The Australian

context. Australian Planner, 43(1), pp.36-41.

Liptay, DM 2009, ‘Creating healthy communities through

urban form’, Master thesis, University of Waterloo,

Canada.

Maas, J, Verheij, RA, Groenewegen, PP, Sjerp de Vries, &

Spreeuwenberg, P 2006, ‘Green space, urbanity, and

health: how strong is the relation?’, Journal of

epidemiology and community health, vol. 60, No.7, pp.

587-592.

Mitchell, R & Popham, F 2007, ‘Greenspace, urbanity and

health: relationships in England’, Journal of

Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 61, No.8,

pp. 681-683.

Montgomery, J 1998, Making a city: urbanity, vitality, and

urban design, Journal Of Urban Design, vol. 3, pp. 93-

116.

Northridge, M, Sclar, E & Biswas, P 2003, 'Sorting out the

connections between the built environment and health:

a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and

planning healthy cities', Journal of Urban Health, vol.

80, no. 4, pp. 556-568

Pudjowati, UR, Yanuwiadi, B, Sulistiono, R & Suyadi,S

2013, ‘Effect of vegetation composition on noise and

temperature in Waru – Sidoarjo highway, East Java,

Indonesia’, International Journal of Conservation

Science, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 459-466.

Ritchie, A, & Thomas, R (ed.) 2013, Sustainable urban

design: an environmental approach, Taylor & Francis.

Rowley, A 1994, Definitions of urban design: the nature

and concerns of urban design, Planning Practice and

Research, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 179-197.

Schiller, SD & Evans, JM 2006, ‘Assessing urban

sustainability: microclimate and design qualities of a

new development’, Paper presented at the the 23rd

conference on passive and low energy architecture, 6-8

September, Geneva, Switzerland.

Schipperijn, J, Ekholm, O, Stigsdotter, UK, Toftager, M,

Bentsen, P, Kamper-Jorgensen, F & Randrup, TB 2010,

‘Factors influencing the use of green space : result from

a Danish national representative survey’, Landscape

and Urban Planning, vol. 95, no. 3, pp 130-137.

Schurch, TW 1999, 'Reconsidering urban design: thoughts

about its definition and status as a field or profession',

Journal of Urban Design, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 5

Taher, S. and Haqi, F.I., 2017, July. Principles of

Waterfront Renovation to Decisive Spaces for Local

Identity: A Study Case of Port Adelaide, South

Australia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and

Environmental Science (Vol. 79, No. 1, p. 012028).

IOP Publishing. doi: https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-

1315/79/1/012028

Takano, T (Ed.) 2003, Healthy cities and urban policy

research. New York, Spon Press.

Un-Habitat, 2009, ‘Planning sustainable cities’, Earthscan,

London.

Werna, E & Harpham, T 1995, ‘The evaluation of healthy

city projects in developing countries’, Habitat Intl, vol.

19, no. 4, pp. 629-641.

World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for

Europe 1997, Twenty steps for developing a healthy

cities project, World Health Organization Regional

Office for Europe, viewed 9 October 2017,

http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1

01009/E56270.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO) 1998, Health

promotion glossary, WHO, viewed 9 October 2017,

http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/about/HPR%20G

lossary%201998.pdf?ua=1

WHO 2010, Why urban health matters: World Health

Organization.

World Health Organization (WHO) 2014, Types of healthy

setting, World Health Organization, viewed 10 August

2017, http://www.who.int/healthy_settings/types/

cities/en/

Urban Parks as a Part of Urban Design Implementation towards Healthy Cities: What Can Be Achieved through the WHOs Healthy Cities

Model?

75