Corpus-driven Analysis on the Language of Children’s Literature

Evynurul Laily Zen

1

1

Universitas Negeri Malang

Keywords:

Corpus-driven; linguistic analysis, children’s literature.

Abstract: This current paper examined distinctive patterns of language that characterize children’s literature using a

corpus-driven approach. I built a limited corpus—CoCL (Corpus of Children’s Literature)—of 28 novels

and short stories that were published in the late 19

th

to the early 20

th

available on Project Gutenberg and

written by four prominent writers; Carlo Collodi, Lewis Carrol, Beatrix Potter and Hugh Lofting. With the

utilization of WMatrix and AntConc as the corpus tools, the 319.968 tokens of CoCL were further analyzed

and compared to the BNC Written Imaginative. The findings demonstrated several features distinguishing

the language of this particular genre to adult fictions including significant uses of noun and subjective

pronoun, explicit articulations of smallness, animals, and food, as well as cultivation of positive vibes,

joyful tones, and optimism. The paper attempted to enrich evidence on the effectiveness of corpora in both

linguistic and literary analysis that was, at the same time, seen to mark the advancement of digital world in

language research.

1 INTRODUCTION

A tradition of story writing for children and

probably also by children has dated back 250 years

ago. This explains that children’s literature has truly

taken thousand miles of development following the

changes of people and their cultures. Kennedy

(2017) points out that it was in the seventeenth

century where children’s literature emerged as an

independent genre stimulated by an increasing

awareness of repositioning children as the center of

agency as well as the point of interest. This was

clearly manifested in the emerging moral values

relevant for children through the portrayal of

adventures together with a massive growth of picture

books in the nineteenth century (Kennedy, 2017).

In the twentieth-century, children stories become

progressively diverse yet remain didactic as they are

written in an age-specific language (Coghlan, 2017;

Leland et al., 2013). In this way, scholars agreed that

children’s literature should be distinctive in a sense

that it should talk about children and use ‘child-

oriented’ language. Taking a child-centeredness as a

point of departure, I put forward a corpus-driven

analysis toward children stories with the aim of

figuring out distinctive features of this specific genre

in comparison to the adult’s literature.

Corpus analysis becomes a primary backdrop of

this paper as I refer to (Llaurado, et al., 2012)

argument stating that corpus linguistics enables

researchers to obtain samples of authentic language

uses in different contexts for various analytical

purposes ranging from capturing developmental

shifts in language use to encapsulating genre specific

features. The employment of corpus is also seen to

be able to build a connecting link between linguistic

analysis and literary interpretation (Hardstaff, 2015;

Cogo, and Dewey, 2012; Forceville, 2006). Through

a corpus-based study, Hardstaff herself carefully

examines child agency and character development

embedded within grammatical patterning in Roll of

Thunder.

In a specific context of children literature analysis,

Hardstaff’s study is influential as it not only

approaches a literary analysis from a different angle,

but also draws a bridging line between two sub-

disciplines. It, at the same time, is able to fill the gap

of previous studies that have repeatedly investigated

children’s literature from a very specific literary

issue in a single story, such as style shifting in Peter

Rabbit (Mackey, 1998; Rudman, 1995), boundaries

of properties in Beatrix Potter’s tales (Blomley,

Laily Zen, E.

Corpus-driven Analysis on the Language of Children’s Literature.

DOI: 10.5220/0009912700170022

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Recent Innovations (ICRI 2018), pages 17-22

ISBN: 978-989-758-458-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

17

2004), animals’ right in Doctor Dolittle (Elick,

2007), and translating animals’ language in Doctor

Dolittle (Hague, 2007; Heine, Narrog, & Biber,

2015).

Following Hardstaff’s line of research, I

specifically work to find prominent linguistic

patterns and literary elements that characterize

children’s literature by making use of corpus data

and corpus tools. More explicitly, my study

replicates Thompson and Sealey's (2007)

comparative analysis of language patterns used in

three corpora: CLLIP (Corpus-based Learning about

Language in the Primary-school), adult fiction, and

newspapers to identify specific features of writing

aimed for child audiences compared to adult

audiences. Their findings demonstrate that the

language of CLLIP and adult fiction was much

similar than those in newspapers. However, in terms

of methodology, Thompson and Sealey (2007) limit

their corpus exploration only on POS (Part of

Speech) tagging analysis. It is therefore necessary to

broaden their investigation on semantic tagging and

concordance analysis to get a closer look at different

picture of linguistic patterns of children’s literature.

In addition, instead of using their corpus data that

they obtain from BNC (British National Corpus)

Imaginative, I build my own corpus that I will

elaborate in the following sub section.

2 METHOD

I employed a corpus-driven approach where the

corpus files were created before being investigated. I

primarily utilized WMatrix and AntConc to locate

keyness/keyword lists, POS tags, Semantic tags, and

concordance analysis by using BNC Written

Imaginative as a reference corpus to reveal regular

patterns of language within the frame of literary

works.

The corpus—I termed it CoCL (Corpus of

Children’s Literature)—was compiled from samples

of novels and short stories published during the late

19

th

to the early 20

th

century. Stories written by

Carlo Collodi and Lewis Carrol were taken to

represent the late 19

th

century, whereas Beatrix

Potter and Hugh Lofting were to represent the early

20

th

. This was the Golden Age of Children’s

Literature in Britain. Avoiding the use of random

sampling, I took those with everlasting international

popularity having been adapted into screen plays as

my corpus data which all are listed in Table 1.

Table1: Corpus of Children’s Literature

Authors Novels/Stories

Year

s Tokens

Carlo

Collodi

The Adventures of

Pinocchio

1881 -

1883

82.869

Pinocchio: the Tale of the

Puppe

t

Lewis

Carroll Alice’s adventures in

1865 -

1889

92.313

wonderland

Through a looking-glass

Beatrix

Potte

r

The Tale of Pete

r

Rabbi

t

1902 -

1930

42.510

The Tale of Squirrel

Nutkin

The Tailor of Gloucester

The Tale of Benjamin

Bunny

The Tale of Two Bad

Mice

The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-

Winkle

The Tale of Samuel

Whiskers

The Tale of the Flopsy

Bunnies

The Tale of Ginger and

Pickles

The Tale of Mrs.

Tittlemouse

The Tale of Timmy

Tiptoes

The Tale of Mr. Tod

The Tale of the Pie and the

Patty-Pan

The Tale of Pigling Bland

The Tale of Mr. Jeremy

Fishe

r

Appley Dapply's Nursery

Rhymes

TheStoryofaFierce Bad

Rabbit

The Tale of Johnny Town-

Mouse

The Story of Miss Moppet

Cecily Parsley's Nursery

Rhymes

The Tale of Tom Kitten

The Tale of Little Pig

Robinson

The Tale of Jemima

Puddle-

Duck

The Tale of Kitty-in-Boots

Hugh

Loftin

g

The Story of Docto

r

Dolittle

1920

–

1921

102.272

The Voyages of Doctor

Dolittle

Total 319.968

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

18

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Linguistic Patterns

To find the most preferred linguistic items used in

children stories, I look at three features: keyness,

POS tags, and Semantic Tags. The keyness analysis

presented in Figure 1 shows that character names

(Alice, Pinocchio, doctor (Doctor Dolittle),

Polynesia) and grammatical bins (nt, the, and, im)

appeared most prominently. This is unsurprising as

these terms should generally appear in all fictional

texts. The word little (988 times), however, can be

claimed as a distinctive feature of CoCL due to its

high frequency compared to the reference corpus

(208 times). This is in line with the result of

semantic tag analysis partly shown in Figure 2 in

which the concept of small occurred more regularly

than big. In this context, little is used to portray

children’s ability in viewing the world and their

surroundings where everything they could see, hear,

taste, and touch must be in an equivalent ‘size’ to

them.

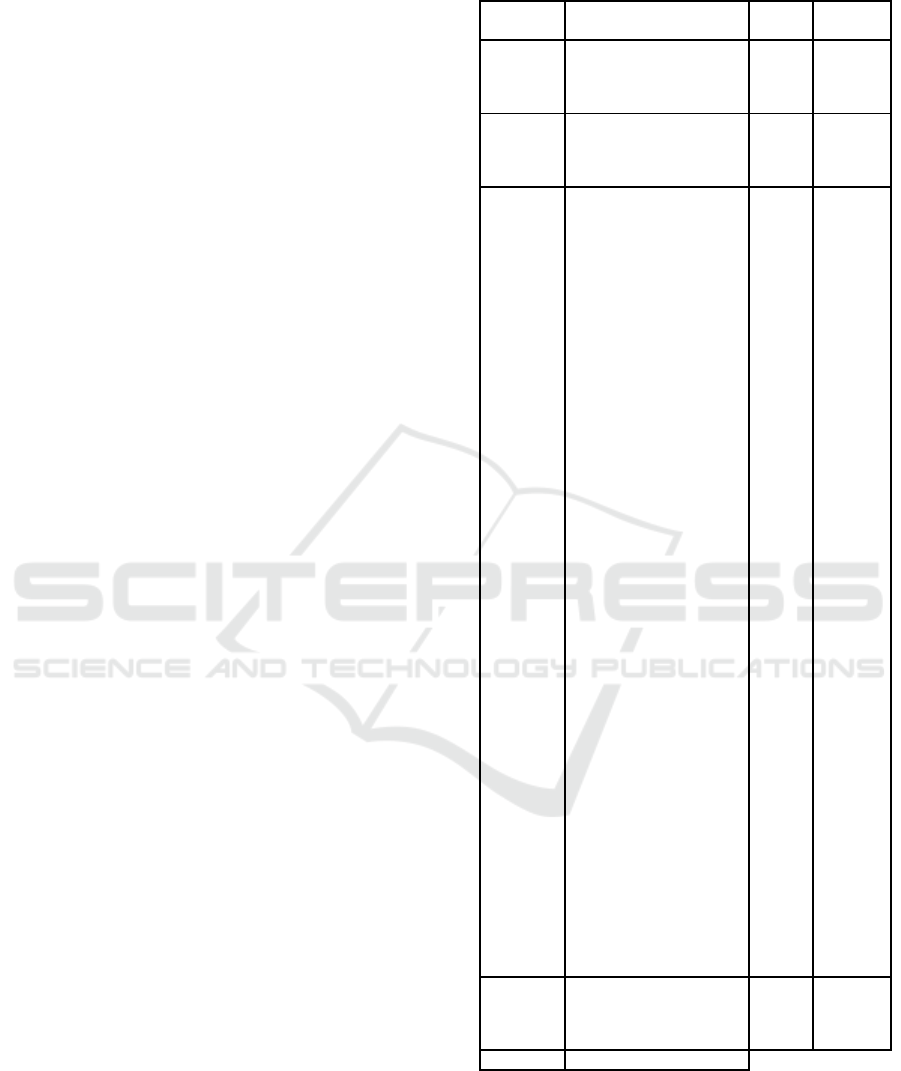

Figure 1: Keyness Analysis

Figure 2: Word Cloud on Semantic Category of Size

Further observation is carried out to find group of

words that collocates with the word little. The result

in Figure 3 indicates that they commonly denotes (1)

human and animals (e.g. man, donkey, boy, girl,

fairy, pig, dog, etc), (2) places (e.g. house, boat), and

(3) objects (e.g. way, door). This particular empirical

evidence has strengthen a claim that children stories

should be child-oriented in the way that they must

contain more concrete objects (either animate or

inanimate) rather than the abstract ones (McDowell,

2006).

POS tagging analysis provides another interesting

point especially when this CoCL is compared to

Thompson and Searley’s (2007) CoAL (Corpus of

Adult’s Literature). The result in Chart 1 illustrates

that the frequency of noun, article, preposition,

pronoun, and conjunction are higher in CoCL than in

CoAL. This significant use of noun and pronoun in

children’s literature has suggested an emphasis of

‘subject’ and ‘object’ in child’s point of view.

Figure 3: R1 Collocates of Little

Chart 1: Comparative POS Tags of CoCL and CoAL

A distinctive pattern of language is further

maintained by the overuse items of semantic

category in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Overuse Items of Semantic Category

The category of living creatures: animals in

Figure 4 appears as the key concept in CoCL. It

suggests that children’s stories were constantly

capturing animals. More importantly, the stories

featured animals as talking creatures that personify

human with their life experiences (e.g. said the crow,

said the four Rabbits, the judge was a monkey, etc.)

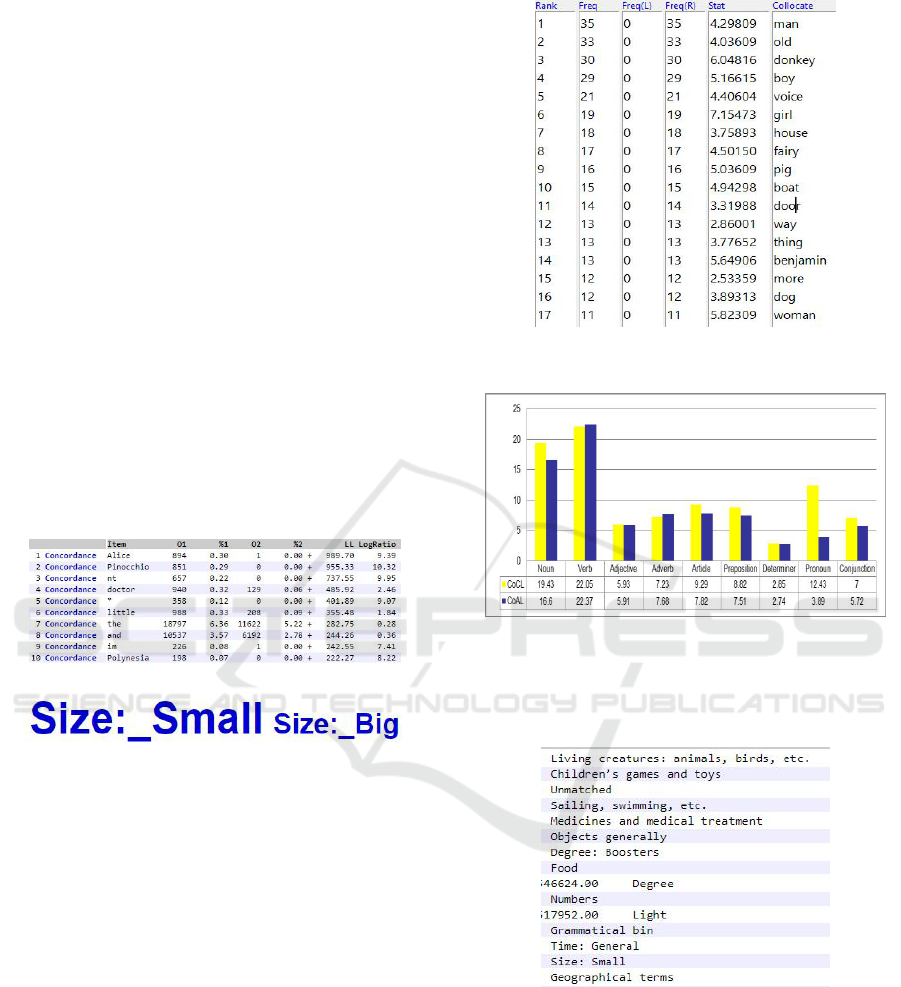

as seen in Figure 5.

Corpus-driven Analysis on the Language of Children’s Literature

19

Figure 5: Concordance of Living Creatures Category

A semantic field of food is fascinating in

particular association to animal. It is to say that

animals’ life is commonly centered around food

finding. A variety of food (e.g. blackberries,

cherries, beans) in Figure 6 is seen to depict a close

connection of animals to their habitat and

environment. The significant use of food in CoCL,

therefore, sustains the importance of it both in

animal and children’s life serving as the basic need

of all living creatures.

Figure 6: Concordance of Food Category

2.3 Literary Elements

Literary elements commonly include settings,

characters, plots, meaning, point of view, and style

(Temple, et al., 2002). In analyzing the outstanding

concepts appeared in children’s literature literary

elements, I look at characters, style and meaning.

To assess the first element, I analyze the use of

pronoun as a relevant POS to describe characters.

Chart 2 below illustrates the comparative use of

pronoun in CoCL and CoAL to pinpoint the findings

that all types of pronoun were exploited more

frequently in CoCL rather than in CoAL. This

finding articulates a critical role played by the

‘agent’ or ‘doer’ in children stories which, to a large

extent, uncovers children’s distinctive point of view

for it seems easier for them to understand who do

things before what things are done. Furthermore,

Chart 2 indicates the greater use of ‘subjective’

pronoun (e.g. I, you, she, he, we, they) and the lesser

use of ‘objective pronoun (e.g. me, us). It supports

the previous claim on the importance of ‘self’ in

childhood which I assume to be shifting in

adulthood.

A closer look at all characters in the CoCL, I find

that 16 out of 119 were human (e.g. Alice, Doctor

Dolittle, Mr. Jackson, etc), whereas 103 out of 119

were animals (e.g. Petter the rabbit, Polynesia the

parrot, Mr. John Dormouse the mouse, etc). This is

predictable as the semantic tag of living creatures:

animal is overused. What I consider interesting is

that these animal characters were mostly portrayed

as male (See Chart 3). This illustrates the focal point

of gender representation as key issues in children

world. With a more thorough examination on this

phenomenon, I believe further study will be able to

provide more elaborate explanation.

Chart 2: Pronoun in CoCL & CoAL

Chart 3: Representation of Gender in CoCL

Style is not stories the authors wanted to tell, but

how stories are delivered through words (Ibid,

2002). In this context, I put forward an idea that

style is to behave similarly to tone as both elements

are about manner of delivering a story to the targeted

audience. The depiction of tone in the delivery of

stories to child readers is of importance. Our general

assumption is that stories about children and adult

will not be delivered using the same tones. Using

this corpus analysis, I aim to find evidence on the

distinctive tone of children’s literature by looking at

the semantic field of emotion (Figure 7).

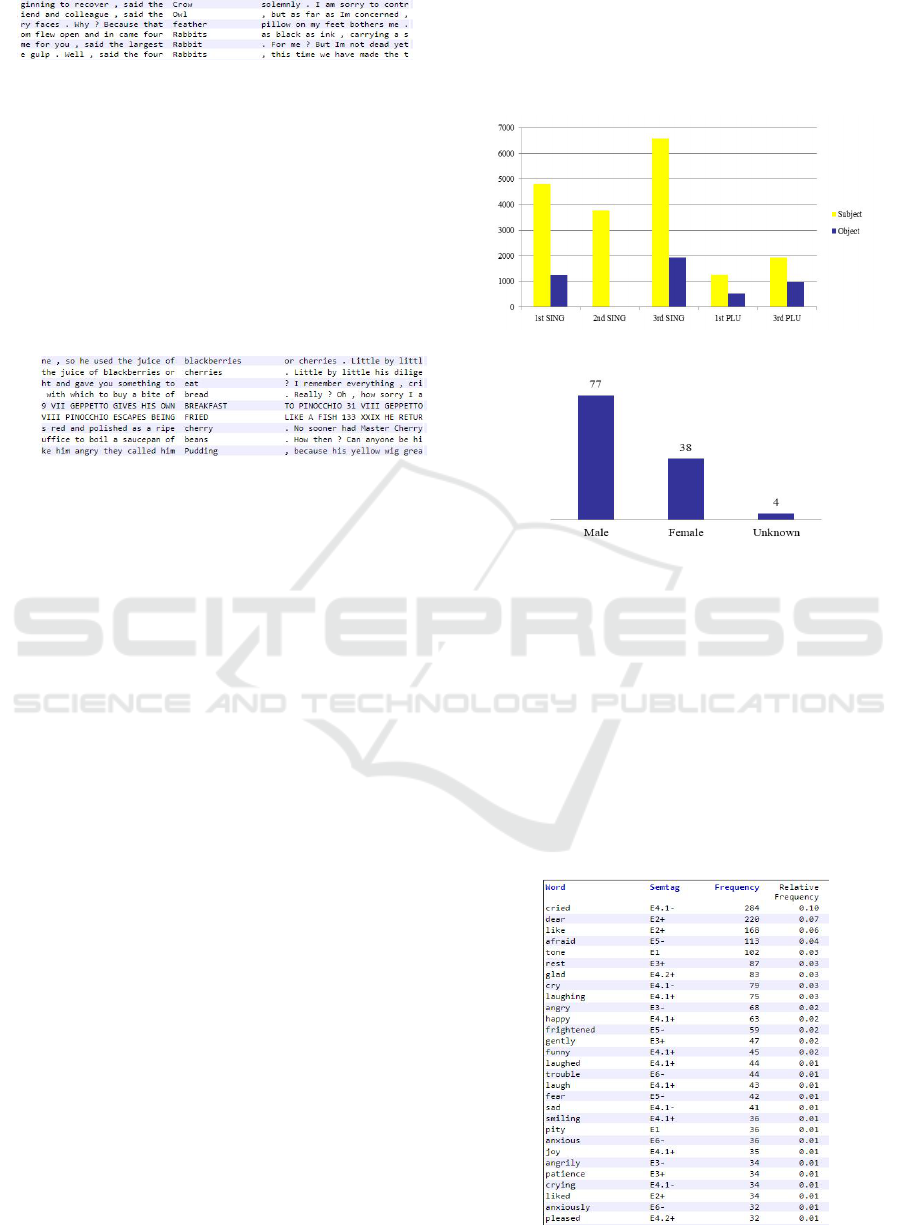

Figure 7: Semantic Category of Emotion

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

20

Words within this field include verbs (e.g. cried,

laughed), adjectives (e.g. funny, glad), and adverbs

(e.g. angrily, anxiously). There seems to be a

tendency to use greater positive emotional

expressions (e.g. gently, joy) and lesser negative

emotional expressions (e.g. angry, frightened) in

CoCL. It strongly implies that children are similar to

adult in the way they experience both joy and

sorrow, but they are different in that joy and all

those enjoyable experiences were valued more.

Also, Figure 7 clearly indicates that words

expressing unpleasantness and sorrow were

underused, whereas pleasantness and joy were

overused. This corpus evidence is in particular

support to the argument stating that children’s books

tend to use language expressing optimism rather

than depression with a major purpose to entertain

children and provide moral values (McDowell,

2006; O’Sullivan and Whyte, 2017; Glynn, 2010;

Guo, 2015).

The meaning of a story can be broadly treated as

certain theme or value to share embedded within that

story. In this way, theme often defines the

segmentation of the readers. Thompson and Sealey

(2007) figured out that intimacy and sex was

frequently used as a theme in adult fiction, whereas

the CoCL demonstrates that nature-related issues

are noteworthy in defining children’s state of mind. I

refer my finding to the semantic categories of

geographical terms (ranked 15

th

), plants (ranked

27

th

), and farming and horticulture (ranked 28

th

). It

is then convincing to claim that nature is the

ultimate necessity that children need to know.

Geographical terms in Figure 8 below, for example,

is seen to function not only as places where daily

activities were conducted, but also things attached to

their daily life.

Figure 8: Concordances of Geographical Terms

In addition, words within the category of

plants (e.g. bushes, trees, flowered) in Figure 9

function more than only as supplementary elements,

but as a center of interests where stories are about.

The semantic field of farming and horticulture in

Figure 10 shows a similar tendency. These all come

to prove that nature is one of the distinctive themes

being valued as the key element of children’s stories.

This supports Pike's (2010) argument on the nature

of spaces in children’s perspective where

fairgrounds, amusement parks, and zoological

gardens are commonly successful in creating an

enjoyment and pleasure for children as they can

interact with the natural world.

Figure 9: Concordances of Plants

Figure 10: Concordances of Farming and Horticulture

However, nature does not seem to be the only

prominent themes in children stories as I figure out

that words reflecting a spirit of optimism are also

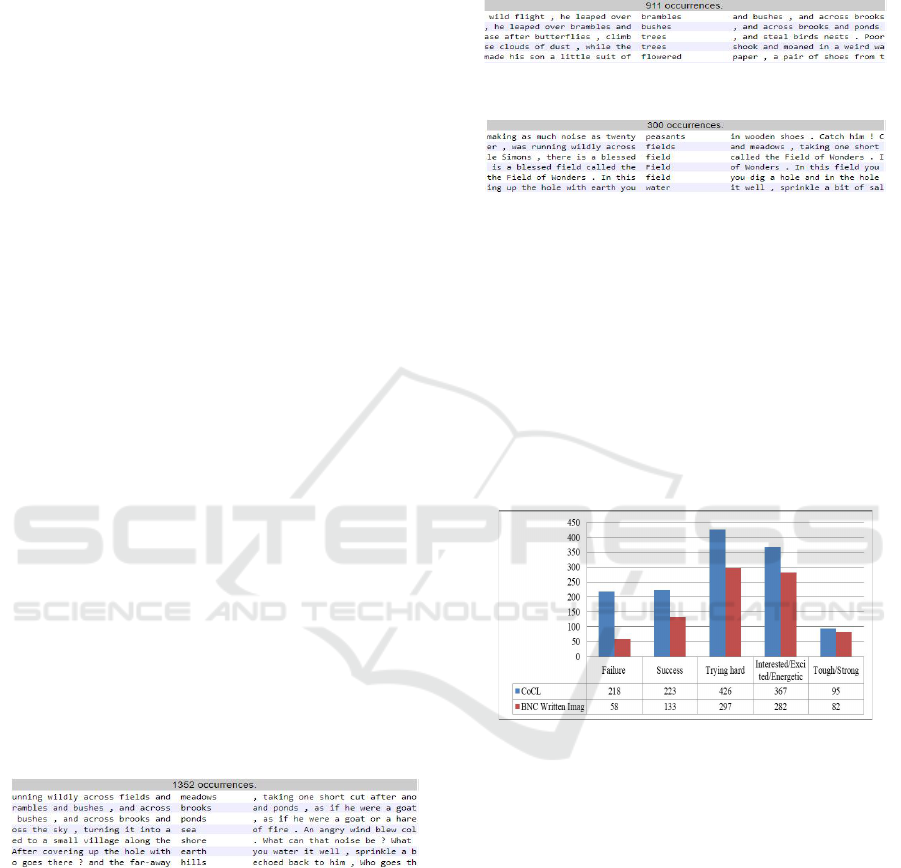

overused. The semantic field of psychological

actions, states, and processes (X) in Chart 4

provides us with the evidence. The overuse items of

this semantic category imply that children stories

have invested an equal probability of failure and

success, the importance of trying hard, and the value

of feeling interested/excited/energetic and

tough/strong to strive for life.

Chart 4: Reflection of ‘Optimism’ in CoCL and BNC

written image.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, a corpus analysis I carried out has

facilitated me in discovering distinctive language

patterns as well as literary elements embodied within

the CoCL (Corpus of Children’s Literature).

Compared to the literary texts written for adults, the

language used in children’s literature tends to be

centered around the idea of smallness, animals, and

food through the significant uses of noun and

subjective pronoun. In terms of literary concepts,

children’s literature tends to cultivate the idea of

personifying animals as talking characters, elevating

positive vibes and joyful tones, making nature and

optimism the most preferable themes of the stories.

Corpus-driven Analysis on the Language of Children’s Literature

21

A corpus of this kind will impart a practical

implication of cross-sectional studies mainly for

pedagogical purposes where it provides teachers

with big data of children stories as well as typical

patterns of children’s language.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was written upon a completion of a term-

paper of Corpus Linguistics Class 2017 at the

Department of English Language and Literature,

National University of Singapore with a special

reference and appreciation for Prof. Vincent Ooi for

his constructive feedback toward the earlier draft of

the paper.

REFERENCES

Blomley, N., 2004. The boundaries of property: lessons

from Beatrix Potter. The Canadian Geographer, 48(2),

91–100.

Coghlan, V., 2017. Picturing possibilities in children’s

book collections. In K. O’Sullivan & P. Whyte (Eds.),

Children’s Literature Collections: Approaches to

Research (pp. 221–240). New York.

Cogo, A. and Dewey, M., 2012. Analysing English as a

lingua franca: A corpus-driven investigation.

Bloomsbury Publishing.

Elick, C. L., 2007. Anxieties of an animal rights activist:

The pressures of modernity in Hugh Lofting’s Doctor

Dolittle series. Children’s Literature Association

Quarterly, 32(4), 323–339.

Forceville, C. 2006. Book Review: Corpus Approaches to

Critical Metaphor Analysis. Language and Literature,

15(4), 402-405. doi:10.1177/0963947006068661

Glynn, D. 2010. Corpus-driven Cognitive Semantics.

Introduction to the field. Quantitative Methods in

Cognitive Semantics: Corpus-Driven Approaches, 1-

42. doi:10.1515/9783110226423.1

Guo Gui-Hang & LI Dan. 2015. A Corpus-Driven

Analysis of Image Construction of BRIC Bank from

Mainstream Media’s Perspective—A Case Study of

China Daily. Journal of Literature and Art Studies,

5(7). doi:10.17265/2159-5836/2015.07.009

Hague, D. R., 2007. Fuzzy memories: Why narrators

forget they translate for animals. Translation and

Literature, 16(2), 178–192.

Hardstaff, S., 2015. ‘“Papa Said That One Day I Would

Understand”’: Examining child agency and character

development in Roll of Thunder , Hear My Cry using

critical corpus linguistics. Children’s Literature in

Education, 46, 226–241.

http://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-014-9231-1

Heine, B., Narrog, H. & Biber, D. 2015. Corpus-Based

and Corpus-Driven Analyses of Language Variation

and Use. The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis.

doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199677078.013.0008

Kennedy, M., 2017. Instruction with delight: Evidence of

children as readers in eighteenth-century Ireland from

the collections of Dublin City Library and Archive. In

K. O’Sullivan & P. Whyte (Eds.), Children’s

Literature Collections: Approaches to Research (pp.

15–32). New York: Palgrave Macmilan.

Leland, C., Lewison, M., & Harste, J., 2013. Teaching

children’s literature: It’s critical! New York and

London: Routledge.

Llaurado, A., Marti, A., & Tolchinsky, L., 2012. Corpus

CesCa: Compiling a corpus of written Catalan

produced by school children. International Journal of

Corpus Linguistics, 17(3), 428–441.

http://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.17.3.06lla

Mackey, M., 1998. The case of Peter Rabbit: Changing

conditions of literature for children. New York and

London: Garland Publishing, Inc.

McDowell, M., 2006. Fiction for children and adults:

Some essential differences. In P. Hunt (Ed.),

Children’s literature: Critical concepts in literary and

cultural studies (pp. 53–67). London and New York:

Routledge.

O’Sullivan, K., and Whyte, P. (Eds.)., 2017. Children’s

literature collections: Approaches to research. New

York: Springer.

Pike, D. L., 2010. Buried pleasure: Doctor Dolittle, Walter

Benjamin, and the nineteenth-century child.

Modernism/Modernity, 17(4), 857–875.

Rudman, M.K., 1995. Children's literature: An issues

approach. Addison-Wesley Longman, 1 Jacob Way,

Reading, MA 01867.

Temple, C., Martinez, M., Yokota, J., and Naylor, A.,

2002. Children’s books in children’s hands: An

introduction to their literature. Boston: Allyn &

Bacon: A Pearson Education Company.

Thompson, P., and Sealey, A., 2007. Through children’s

eyes ? Corpus evidence of the features of children’s

literature. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics,

12(1), 1–23.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

22