A Framework for Performance Management of Clinical Practice

Pilar Mata

1

, Craig Kuziemsky

2

and Liam Peyton

1

1

Faculty of Engineering, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

2

Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Keywords: Evaluation and Use of Healthcare IT, Healthcare, Performance Management, Mobile Technologies for

Healthcare Applications, Software Systems in Medicine, Design and Development of Methodologies for

Healthcare IT.

Abstract: In this paper, we present a framework for performance management of clinical practice. The framework

defines a performance management participation model, which identifies the processes that need to be

managed at the micro, meso, and macro levels for a clinical practice, and which identifies the key actors and

tasks relevant to performance management. It defines a performance measurement model, which maps goals

and indicators to the performance management participation model. In addition, it includes a methodology

for implementation and evaluation of tools that can be integrated into care processes to support the data

collection and report notification tasks identified in the performance management participation model. We

revisit the case study of implementing a resident practice profile app, in light of the proposed framework, to

support performance management of a family health practice. We demonstrate how the framework is useful

for explaining why the use of the app was abandoned after two years of its introduction and, therefore, how

the framework is an improvement to our previous methodology for development of performance

management apps for clinical practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Performance management frameworks are

implemented in healthcare organizations in response

to an increasing need for accountability and

transparency and to stimulate improvements in

quality of care (Marshall et al., 2018). Adoption of

performance management in the healthcare industry

is slower compared to other industries (Crema and

Verbano, 2013). One key reason for this is the

complexity of the healthcare system compared to

other domains. Healthcare delivery encompasses

multiple stakeholder groups (patients, families,

health plans, practitioners, communities, regulators,

etc.) and actors (Voelker et al., 2001; Lipsitz, 2012).

Synchronization of data, people, processes, and

technology is needed to achieve seamless integration

in support of performance management across

patient and healthcare providers routines (Avison

and Young, 2007; Benson, 2012).

We propose a performance management

framework for clinical practice that provides:

a. A performance management participation model,

which identifies the processes that need to be

managed at the micro, meso, and macro levels for a

clinical practice, and which identifies the key actors

and tasks relevant to performance management.

b. A performance measurement model which maps

goals and indicators to the performance management

participation model.

c. A methodology for implementation and

evaluation of tools that can be integrated into care

processes to support the data collection and report

notification tasks identified in the performance

management participation model.

The motivation for this framework, grew out of

previous work to create a development methodology

for performance monitoring apps (Mata et al., 2015).

The methodology was successful for quickly

developing user-friendly apps for collecting and

reporting on performance monitoring data. However,

organizational adoption was limited because it did

not provide a broad enough perspective on the

context in which the apps would be used as part of a

complete performance management system for an

entire clinical practice. We define a clinical practice

as a collection of processes that, together, support a

particular type of healthcare for a particular

286

Mata, P., Kuziemsky, C. and Peyton, L.

A Framework for Performance Management of Clinical Practice.

DOI: 10.5220/0007375902860293

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2019), pages 286-293

ISBN: 978-989-758-353-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

community of patients. This work focuses on our

main research question of how to effectively and

efficiently guide the implementation and adoption of

performance management systems for a clinical

practice, considering the complexity of healthcare

systems. We revisit a case study of implementing a

resident practice profile app to support performance

management of a family health practice in order to

demonstrate the usefulness of our proposed

performance management framework.

2 BACKGROUND

Performance management involves systematic

planning, execution, monitoring and evaluation of

goals in order to improve business effectiveness

(Dresner, 2008).

(Marshall et al., 2018) review implementations

of healthcare quality report cards (also called report

cards or, performance cards) in the United States and

United Kingdom. Their work shows that although

reporting is perceived as a key factor for improving

accountability and quality in the health care system,

often there are challenges in engaging the

stakeholders on these initiatives.

The Sunnybrook Hospital in Ontario, published

its Balance Scorecard & Patient Safety Indicators in

June 2018, with the goal to increase transparency for

the community (Sunnybrook, 2018). The Balanced

Scorecard includes the dimensions: quality of patient

care, research and education, and sustainability and

accountability.

Despite the complexity of

implementing performance management systems

like Balanced Scorecard in healthcare organizations,

research shows some progress in this area.

Achieving a successful implementation of it requires

communication, commitment and, support from all

stakeholders and at all the different organizational

levels (Voelker et al., 2001).

While information technology is critical for

performance management in healthcare,

interoperability is an ongoing challenge for

healthcare information systems (HIS) (Kuziemsky

and Peyton, 2016). However, HIS to support

performance management must go beyond a single

technological solution. The complexity of healthcare

system means a single vendor cannot have the best

solution for all functions, even within a single

hospital (Gaynor et al., 2014).

There are different types of interoperability and

these can be grouped, at a high level, into three main

categories: technical, semantic and processes

interoperability (Benson, 2012).

Technical interoperability is defined as the

ability to move data from system A to system B

regardless of the meaning of what is being

exchanged (Benson, 2012). Technical

interoperability is achieved through mHealth and

eEhealth. “mHealth” is defined as the use of mobile

technologies in the healthcare industry to support

public and clinical care (Kahn et al., 2010), while

“eHealth” involves the use of any type of electronic

devices, e.g desktops, in the provision of health care

(Dicianno et al., 2015).

Semantic interoperability is defined as the ability

of sender and receiver to understand data without

ambiguity. It refers to the ability of two computer

systems to be able to interpret and understand data

that is exchanged (Benson, 2012). Standards

developed to support semantic interoperability

include HL7 and terminology models such as

Systematic Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical

Terms (SNOMED-CT) and Logical Observation

Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) (Dixon et al.,

2014).

Process interoperability refers to the coordination

of business and work processes and common

understanding between human beings across a

network (Benson, 2012). The latter includes one of

the key dimensions in healthcare delivery - the

interpersonal nature of care delivery (Avison and

Young, 2007). Encounters between care providers

and patients (e.g doctors and patients, patient and

nurses, patient and therapists, nurses and doctors) to

discuss diagnosis, treatment options, treatment

progress, etc. is an important dimension to consider

in healthcare interoperability; however, the process

interoperability is often forgotten when designing

systems to support healthcare delivery.

Clinical performance management can be

approached in two ways. First, performance can be

seen as the outcome of a process. An example of

performance monitoring in this case would be

monitoring mortality rates. Second, clinical

performance can be seen at the process level, which

in the end, impacts outcome (Goddard et al., 2002).

An example of performance monitoring of a clinical

process would be monitoring a patient from

diagnosis to end of treatment to gain insights of

patient status and progress against goals.

Performance monitoring of clinical process can

facilitate timely actions during the treatment of the

condition.

Information, process and personnel issues can

contribute to gaps in data support for decision-

related processes in Canadian Healthcare

organization (Foshay and Kuziemsky, 2014). To

A Framework for Performance Management of Clinical Practice

287

address these issues organizations should employ a

process framework to define information needs

when implementing performance management

systems. Further, the impact of data on clinical

practice needs to be analysed in different user

contexts (Kuziemsky et al., 2014). A process

framework should distinguish between the micro

level (direct patient care), the meso level

(management and evaluation of care providers), and

the macro level (public health and regulatory

processes).

3 FRAMEWORK

In this section we describe the components of our

proposed framework for performance management

of a clinical practice (Figure 1). Research methods

used for the development of the framework include:

1) literature review 2) Gap analysis of existing

frameworks (Perlin et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2012;

Voelker et al., 2001; Sullivan et al., 201; Potter et al.

2011) 3) Use of Design Science Method (Peffers et

al., 2007) for defining, designing, and building the

conceptual framework. The developed framework is

comprised of a performance management

participation model, a performance measurement

model, and a methodology for implementation and

evaluation of supporting tools.

Figure 1: Framework for Performance Management of

Clinical Practice.

In the 'Performance Management Participation

Model' we identify which tasks are performed by

which actors in the context of a process, and then

model processes that need to be monitored for

performance management. This is done at a

conceptual level and includes identifying the actors,

tasks and task types for each process. The

participation model is intended to facilitate

discussion among stakeholders and achievement of a

common vision of the process in terms of

performance management. The 'Performance

Measurement Model' is used to define which goals

and indicators will be used for performance

management of each process, based on what report

notifications the actors need and for which processes

the reports are needed. Relationships between the

'Performance Management Participation Model' and

the 'Performance Measurement Model' imply

iterative cycles for the development of conceptual

models - mapping processes to goals, tasks to data

collection, data collection to indicators, indicators to

report notifications and report notifications to tasks.

Finally, tools used to implement performance

management of a clinical practice are identified and

mapped to data collection and report notification

tasks that use the tools to populate the performance

management model. Relationships are defined for

the processes at all organizational levels to ensure all

actors receive the appropriate information to

perform their tasks. Once data needs are clear (from

collecting and reporting), the next step in the

framework is a systematic approach to implementing

and evaluating tools that support the set of tasks

defined in the performance management

participation model. We update and integrate a

methodology for development of performance

monitoring apps (Mata et al., 2015).

4 CASE STUDY OF A RESIDENT

PRACTICE PROFILE FOR

FAMILY HEALTH

Resident Practice Profile (RPP) is a tool for tracking

patient encounters seen by medical residents in

Family Health, to ensure they gain competency

across a broad range of family health diagnoses, and

a diverse range of patients (based on age, gender,

and social circumstance). Residents log data for

patient encounters and the data is used to show

residents where residents are spending their time.

RPP was successfully developed as a user-friendly

app using a development methodology for

performance monitoring apps (Mata et al., 2015).

However, two years after its introduction, it was no

longer used by the organization.

In this case study, we take a broader view of

performance management for the clinical practice as

a whole in order to understand why RPP did not

succeed. Since RPP was developed previous to the

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

288

proposed framework, we evaluate the app, using the

framework, to demonstrate how the framework can

be used to validate any existing tool within a

performance management system and how the

framework is an improvement to our previous

methodology (Mata et al., 2015) for development of

performance management apps for clinical practice.

In the following sections, based on our framework,

we evaluate the use of RPP to support performance

management of medical residents in a family health

practice.

4.1 Evaluation of RPP using the

Framework

4.1.1 Participation Model

In this section, we identify processes, actors, tasks

and task types relevant for performance management

of medical residents in a family health practice.

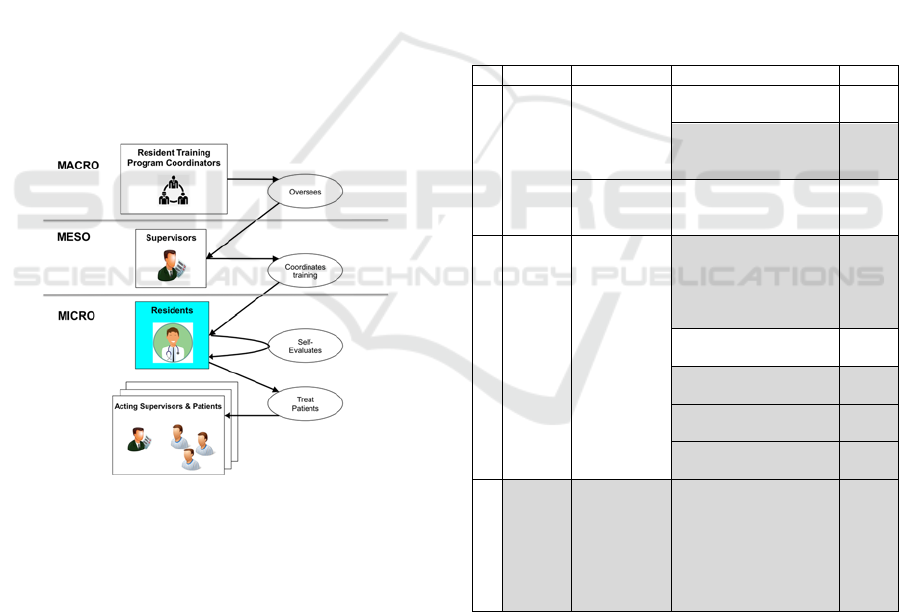

Figure 2 depicts actors, and processes for

performance management of residents at the

different organizational levels (macro, meso, and

micro).

Figure 2: Performance management of training of family

medicine residents – Actors and processes.

At the macro level, Residents Training Program

Coordinators oversee supervisors who coordinate

training for the family health practice. They must

ensure the program adheres to guidelines specified

by The College of Family Physicians of Canada.

At the meso level, supervisors coordinate

training tasks, assigning residents to various clinical

settings and providing feedback on training to ensure

residents are exposed to a variety of clinical

conditions and demographics that lead to successful

attainment of required competencies outlined in the

program curriculum.

At the micro level, residents work under the

supervision of acting supervisors at each clinical

location. Residents are responsible for keeping a log

of conditions seen during practice in order to

demonstrate their competence in all program

requirements - clinical domains and demographic

groups (Chamney et al., 2014). Residents are also

responsible for sharing logs with their supervisors

and flagging visits they want to discuss with their

supervisors to receive feedback and develop a

learning plan, if need be. Also, they are responsible

for proactively identifying and completing self-

learning opportunities. Supervisors use the

information provided by residents for guiding

training and correcting any deficiencies in practice,

e.g. assignment of residents to specific locations

where they can see more cases of a given clinical

condition, creating a learning plan, etc.

Table 1: RPP Performance Management Participation

Model.

Actors Process Tas

k

Type/Task Tool

Micro

Residents

Treat Patients

Data Collection: Log

every patient visi

t

RPP

Data Collection: Record

selected Patient field

note

Field

Note

Self-Evaluate

Report Notification:

Self-Evaluation with

RPP reports

RPP

Meso

Supervisors

Coordinates

Training

Data Collection:

Log Direct

observation/Complete

examination/procedure

or delivery o

b

served

Field

Note

Report Notification:

Review RPP Reports

RPP

Report Notification:

Review Field Note

Field

Note

Report Notification:

Provide Feedbac

k

Field

Note

Data Collection: Assess

level of competency

Field

Note

Macro

Program

Coordinators

Oversees

Report Notification:

Review compliance of

training program against

standards

Field

Note

In Table 1 we summarize processes, actors,

tasks, task types and tools by organizational levels

for RPP. Actors, tasks and task types shaded in grey

represent those that are not supported by the

implementation of RPP. Tasks in bold indicate those

that should have been supported by RPP when it was

implemented, but were not. The RPP app was

designed to be used by residents. As such, it was

A Framework for Performance Management of Clinical Practice

289

Table 2: RPP Performance Management Participation/Measurement Model.

Actors Process Goals Indicators Task

Micro

Residents

Treat Patients

Ensure full

competency across

clinical domains and

population types

Total Visits Log every patient visit

Completed field notes and sent to

supervisors

Record selected patient field note

Self-Evaluates Close gaps in learning

Total visits flagged for

self-learning activities

Self-Evaluation with RPP reports

Meso

Supervisors

Coordinates

Training

Ensure graduated

residents is fully

competent

Total visits Reviews RPP reports

Field Notes completed Review Field Note

Field Notes completed Provide feedbac

k

Field notes signed off Assess level of competency

Total direct observations Assess level of competency

Level of competency achieved Asses level of competency

Macro

Program

Coordinators

Oversees

Ensure compliance of

program to standards

Total visits

Review compliance of training

program against standards

Average success rate: field notes

signed off/total field notes

Review compliance of training

program against standards

good for self-evaluation. However, the data was also

relevant to the supervisors of the residents. In the

original case study, it was assumed that supervisors

would review with the resident what patients they

were seeing, but procedures were not put in place to

do ensure this was done, nor was there any

mechanism for notifying and providing supervisors

with RPP reports relevant to a resident they were

supervising.

4.1.2 Measurement Model

The next component of the proposed framework

involves the development of a performance

measurement model. This includes definition of

goals to gauge progress and indicators for report

notifications. Table 2 summarizes the performance

measurement model for RPP. Goals and indicators

are grouped by organizational level. Goals and

indicators shaded in grey represent those that are not

supported by the implementation of RPP. Goals and

indicators in bold indicate those that should have

been supported by RPP when it was implemented,

but were not.

The most important aspect of the performance

measurement model in this case study is the clinical

practice as it relates to the training of medical

residents. The main questions to answer are; which

goals we need to measure, what report notifications

are needed for supporting and monitoring these

goals, which tasks are needed to collect data, and,

therefore, what data model (dimensions and

indicators) needs to be implemented.

With respect to the RPP tool, the main indicators

supported were total visits and total visits flagged

for self-learning activities. This included the ability

to analyse based on the age, gender and social

circumstances of patients. RPP was designed to

support actors, tasks, and goals at the micro level.

However, as is clear in Table 2, for effective

integration into a system of performance

management, RPP also needed to provide support

for actors at the meso and even the macro level.

Because RPP was not integrated at this level, its use

was not reinforced by supervisors. Therefore, there

was less interest from residents, and it was

eventually phased out of use in the family health

practice.

4.1.3 Methodology

The original methodology was intended for

development of a stand-alone app for performance

monitoring. We have updated the methodology, to

integrate it into a framework for performance

management across an entire clinical practice, with

the focus on the implementation and evaluation of a

set of tools to support data collection and reporting

tasks at all organizational levels (micro, meso,

macro).

Figure 3 shows the updated methodology, with

changes highlighted in Bold. This included defining

clearly who needed to not only use the app for data

collection, but also who needed to see reports

created from the data collected. Adoption criteria

were extended beyond ease of use, to also include an

understanding of the full context for performance

management in which the app would be used.

New components highlighted in red were also

added to the methodology. This included selecting

which tools were available and could be used, and

carefully mapping all tasks (both data collection and

report notification) that needed to be supported by

the tool. The new methodology provides better gui-

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

290

Figure 3: Updated Methodology for Implementation and Evaluation of Tool Support.

dance for understanding who uses the data (actors

that receive report notifications), the context in

which data is used, and what drives adoption

criteria.

4.1.4 Results

After analysing the design of RPP in light of the

framework, we identified that the main focus for the

development of RPP was on monitoring the process

at the micro level by providing residents with a

supporting tool for guiding self-learning activities.

RPP was also useful for providing residents and

program coordinators information about number of

clinical conditions seen by demographic groups as

well as procedures performed. However, the tool

was not used to support supervisors in their task of

providing feedback to residents, designing a plan to

correct any deficiencies identified during training or

completing a formal evaluation of training.

We can say that with our framework, a more

complete view of RPP is given within the context of

supporting performance management of the family

health practice across all levels (micro, meso, and

macro). In the original case study, RPP was

implemented and adopted with some success at the

resident level (micro). Residents found RPP reports

useful for self-assessment and for guiding self-

learning activities.However, the performance

management participation model clearly highlights

the need to provide RPP reports to supervisors for

the tasks of providing feedback to residents or

creating learning plans to address identified gaps in

practice. Report notifications were not implemented

and review of reports was exclusively driven by the

self- motivation of participants of the study.

The performance measurement model also

clearly indicates that total visits, especially as

broken down to support training related to diversity

of patients (age, gender, social circumstance) is

relevant to coordinators at the macro level.

Finally, the updates to the methodology for

implementing and evaluating tools would have more

clearly established the adoption criteria for

evaluating tools in the context of selecting what

tools would be mapped to what tasks for the overall

success of performance management in the family

health practice.

This is the essential factor that explains why RPP

was abandoned even though it was an easy-to-use

app. The fact that the app complied with user

requirements at the individual level (micro level)

was not a sufficient condition to drive adoption of

RPP as a tool for supporting key actors and tasks

relevant to performance management at the meso

and macro levels. The adoption of RPP at the micro

level was exclusively driven by the motivational

aspect of residents who saw value in using the app

for self-assessment of their practice and for guiding

self-learning activities.

The use case provides evidence on the

importance to approach performance management

from a broad enough organizational perspective and

within the context in which the apps would be used,

in order to address information needs of stakeholders

and ensure adoption of the proposed system. Results

A Framework for Performance Management of Clinical Practice

291

of the case study will be used to cross-validate the

usefulness of the framework with clinical experts,

other researchers and for different clinical practices.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we demonstrate the importance of

having a clear understanding of areas that need to be

addressed for effective implementation of tools and

apps that support performance management of a

clinical practice. The findings we presented here

suggest that defining processes, actors, and

performance management tasks across all

organizational levels (micro, meso, and macro) are

key to ensure adoption of performance management

systems for a clinical practice. Our framework

provides a systematic approach to gain consensus

about who needs to manage performance, what

needs to be monitored, how performance will be

reported to key actors, and how to evaluate tools to

systematically support performance management of

a clinical practice.

One limitation of this work is that we used our

framework to retrospectively evaluate the

deployment of one stand-alone app. Although it let

us highlight missing areas for deployment of the app

and why the app was only adopted, with some

success, at the micro level, more research needs to

be done to confirm the framework can also be used

for guiding the design and implementation of a

performance management system for an entire

clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NSERC Discovery

and CREATE initiatives and Ontario Graduate

Scholarship funding.

REFERENCES

Avison, D. and Young, T. (2007) ‘Time to rethink health

care and ICT?’, Commun. ACM, 50(6), pp. 69–74.

Benson, T. (2012) ‘Principles of health interoperability

HL7 and SNOMED. Chapter 2: Why interoperability

is hard.’, in. Springer Science & Business Media

(Principles of health interoperability HL7 and

SNOMED.).

Chamney, A., Mata, P., Viner, G., Archibald, D. and

Peyton, L. (2014) ‘Development of a Resident Practice

Profile in a Business Intelligence Application

Framework’, Procedia Computer Science, 37(0), pp.

266–273.

Crema, M. and Verbano, C. (2013) ‘Future developments

in health care performance management’, Journal of

Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 6, pp. 415–421.

Dicianno, B. E., Parmanto, B., Fairman, A. D., Crytzer, T.

M., Daihua, X. Y., Pramana, G., Coughenour, D. and

Petrazzi, A. A. (2015) ‘Perspectives on the evolution

of mobile (mHealth) technologies and application to

rehabilitation’, Physical therapy. American Physical

Therapy Association, 95(3), pp. 397–405.

Dixon, B. E., Vreeman, D. J. and Grannis, S. J. (2014)

‘The long road to semantic interoperability in support

of public health: experiences from two states’, Journal

of biomedical informatics. Elsevier, 49, pp. 3–8.

Dresner, H. (2008) The performance management

revolution: Business results through insight and

action. John Wiley & Sons.

Foshay, N. and Kuziemsky, C. (2014) ‘Towards an

implementation framework for business intelligence in

healthcare’, International Journal of Information

Management, 34(1), pp. 20–27.

Gaynor, M., Yu, F., Andrus, C. H., Bradner, S. and Rawn,

J. (2014) ‘A general framework for interoperability

with applications to healthcare’, Health Policy and

Technology. Elsevier, 3(1), pp. 3–12.

Goddard, M., Davies, H. T., Dawson, D., Mannion, R. and

McInnes, F. (2002) ‘Clinical performance

measurement: part 1--getting the best out of it’,

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. The Royal

Society of Medicine, 95(10), pp. 508–510.

Kahn, J. G., Yang, J. S. and Kahn, J. S. (2010) ‘“Mobile”

health needs and opportunities in developing

countries’, Health Affairs. Health Affairs, 29(2), pp.

254–261.

Kuziemsky, C.E. and Peyton, L., 2016 (2016) ‘A

framework for understanding process interoperability

and health information technology’, Health Policy and

Technology, 5(2), pp. 196–203.

Kuziemsky, C. E., Monkman, H., Petersen, C., Weber, J.,

Borycki, E. M., Adams, S. and Collins, S. (2014) ‘Big

Data in Healthcare - Defining the Digital Persona

through User Contexts from the Micro to the Macro.

Contribution of the IMIA Organizational and Social

Issues WG’, Yearbook of medical informatics, 9(1),

pp. 82–89.

Lipsitz, L. A. (2012) ‘Understanding Health Care as a

Complex System: The Foundation for Unintended

Consequences’, JAMA, 308(3), pp. 243–244.

Marshall, M. N., Shekelle, P. G., Davies, H. T. O. and

Smith, P. C. (2018) ‘Public Reporting On Quality In

The United States And The United Kingdom In both

countries the imperatives of accountability and quality

improvement make the wider development and

implementation of report cards inevitable’. Available

at: www.ncqa.org. (Accessed: 22 July 2018).

Mata, P., Chamney, A., Viner, G., Archibald, D. and

Peyton, L. (2015) ‘A development framework for

mobile healthcare monitoring apps’, Personal and

Ubiquitous Computing. Springer London, 19(3–4), pp.

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

292

623–633.

Parsons, A., Mccullough, C., Wang, J. and Shih, S. (2012)

‘Validity of electronic health record-derived quality

measurement for performance monitoring’, J Am Med

Inform Assoc, 19, pp. 604–609.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A. and

Chatterjee, S. (2007) ‘A Design Science Research

Methodology for Information Systems Research’,

Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3),

pp. 45–77.

Perlin, J. B., Kolodner, R. M. and Roswell, R. H. (2004)

‘The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value,

accountability, and information as transforming

strategies for patient-centered care’, The American

journal of managed care, 10(11 Pt 2), p. 828.

Potter, K., Fulk, G. D., Salem, Y. and Sullivan, J. (2011)

‘Outcome Measures in Neurological Physical Therapy

Practice: Part I. Making Sound Decisions’, Journal of

Neurologic Physical Therapy, 35(2), pp. 57–64.

Sullivan, J. E., Andrews, A. W., Lanzino, D., Peron, A.

and Potter, K. A. (2011) ‘Outcome Measures in

Neurological Physical Therapy Practice: Part II. A

Patient-Centered Process’, Journal of Neurologic

Physical Therapy, 35(2), pp. 65–74.

Sunnybrook, H. S. C. (2018) Sunnybrook’s Strategic

Balanced Scorecard. Available at:

https://sunnybrook.ca/uploads/1/welcome/strategy/bal

anced_scorecard_june-2018-release.pdf (Accessed: 28

July 2018).

Voelker, K. E., Rakich, J. S. and French, G. R. (2001)

‘The Balanced Scorecard in Healthcare Organizations:

A Performance Measurement and Strategic Planning

Methodology’, Hospital Topics, 79(3), pp. 13–24.

A Framework for Performance Management of Clinical Practice

293