Web Scraping Online Newspaper Death Notices

for the Estimation of the Local Number of Deaths

Rainer Schnell and Sarah Redlich

University of Duisburg-Essen, Research Methodology Group, Forsthausweg 2, 47057 Duisburg, Germany

Keywords:

Administrative Data, Web Data, Mortality, Undercoverage, Big Data, Obituaries.

Abstract:

Since access to real-world data is often tedious, web scraping has gained popularity. A health research example

is the monitoring of mortality rates. We compare the results of local online death notices and print-media

obituaries to administrative mortality data. The web scraping process and its problems are being described. The

resulting estimates of death rates and demographic characteristics of the deceased are statistically different from

known population values. Scaped data resulted in a sample that is more male, older and contains less foreign

nationals. Therefore, using web scraped data instead of administrative data cannot be recommended for the

estimation of death rates at this time for Germany.

1 INTRODUCTION

Extracting information from websites has become in-

creasingly popular as a data source. For example, web

scraping has been used for finding unpublished litera-

ture or for efficiently creating lists of contact informa-

tion (Haddaway 2015; Le and Pishva 2015). However,

scraped data is also used for statistical purposes, for

example, Barcaroli et al. (2016) updated farm regis-

ters using scraped information. Another example is the

augmentation of traditional data by scraped data for

the estimation of job vacancy statistics (Swier, 2017).

For the estimation of death rates, for example, dur-

ing a flu epidemic, timely access to mortality data is es-

sential. In countries with decentralized organizational

structures such as Germany with about 10.000 inde-

pendent local death registries and no federal mortality

database, getting such data is a lengthy process. In

other countries with similar organizational structures,

some unconventional data sources have been used.

For example, in Geneva, Switzerland funeral homes

have been proved to be a reliable source (Mpinga et al.,

2014). They found for a six-year period only a 4.8%

discrepancy on average for the number of deaths be-

tween funeral homes and official state registries.

Another obvious data source is newspaper death

notices. Since online death notices are even easier

to access than newspaper publications, online obit-

uaries may provide information on mortality easily.

In the US, online newspaper death notices have been

used to get information on deceased persons (Boak

et al. 2007; Soowamber et al. 2016). A recent study

by Sylvestre et al. (2018) compared online obituaries

to health records of cancer patients in Rennes, France.

They found high overall accuracy (positive predictive

values between 98% and 100%, negative predictive

value 99%), when linking the two data sets.

To test the feasibility of this approach in a differ-

ent cultural setting, we obtained research access to the

official death registry of one of the largest towns in

Germany (about 600.000 citizens) and compared infor-

mation on the deceased with online newspaper death

notices extracted using a web scraper. The databases

were matched by record linkage using names, date of

birth and date of death. We computed undercoverage

and bias in estimates by comparing the scraping results

to the death registry.

In section 2, we describe the advantages and prob-

lems of web scraping, and discuss the ethical and legal

concerns when extracting death notices. We also ad-

dress some issues encountered during scraping. In sec-

tion 3 we compare demographic differences of the de-

ceased between scraped and administrative data. Sec-

tion 4 concludes.

2 WEB SCRAPING

Web scraping is the extraction of data of interest such

as text, pictures or links from the world wide web

(Chow, 2012). In the literature, it is sometimes referred

Schnell, R. and Redlich, S.

Web Scraping Online Newspaper Death Notices for the Estimation of the Local Number of Deaths.

DOI: 10.5220/0007382603190325

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2019), pages 319-325

ISBN: 978-989-758-353-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

319

to as web harvesting, web crawling, and web mining.

While web harvesting can be used as a synonym to

web scraping, the definitions of web crawling and web

mining do not allow for an interchangeable use (Gatter-

bauer 2009, 3472; Bharanipriya and Kamakshi Prasad

2011, 211; Najork 2009, 3462).

The respective class of programs is referred to as

web scrapers (Najork, 2009). They imitate the interac-

tion of a human with a server and perform the same

tasks a human would perform to get the information

of interest, but in a shorter amount of time. In detail,

they access the web page and search the underlying

HTML-code using regular expressions. When the in-

formation required is found, they extract it and copy it

to a pre-defined output file (Glez-Pe

˜

na et al., 2013, 789

f.). The obtained information usually has to be cleaned

and checked after extraction. A web scraper can be a

library, a framework or a desktop-based environment

(Glez-Pe

˜

na et al., 2013, 789 f.). The last option enables

the use of web scraping without prior knowledge of a

programming language (Glez-Pe

˜

na et al., 2013, 790

f.).

Web scraping has numerous advantages and dis-

advantages. Advantages are time-efficiency, the pos-

sibility of a regular data collection with shorter time

intervals, the reduction of costs, avoidance of response

burden of survey respondents, no survey response ef-

fects such as social desirability bias, and enhancing

the quality of statistics resp. the amount of information

(Landers et al. 2016, 2; Hoekstra et al. 2010, 6 f., 15).

The disadvantages are the necessity for the skills to

write a web scraper, changes of the underlying HTML-

code of websites, lack of automatic plausibility checks

when extracting data, and ethical and legal concerns

(Hoekstra et al., 2010, 7 f.). Furthermore, there is a

chance that the web scraper overloads the servers or

enhances the costs for the owner of the website for

needing a larger bandwidth (Koster 1993b; Thelwall

and Stuart 2006, 1776). Given the increasing band-

width and capacity of web servers, this objection seems

to be negligible. The remaining problems are mostly

ethical problems.

2.1 Ethical and Legal Concerns

When extracting information from websites using a

web scraper, the information is derived without the

knowledge and consent of the individuals such as the

person whose information is retrieved, the provider of

the website and in the case of death notices relatives

of the deceased person (van Wel and Royakkers, 2004,

129). Although, the websites

robots.txt

, which reg-

ulates the access by robots, can be used to stop web

scrapers from accessing the information presented on

the website (Koster 1993a; Thelwall and Stuart 2006,

1775), it should be noted, that the

robots.txt

can

be bypassed. Ethically and legally the laws for web

scraping have to be followed.

Regarding the legal concerns, national laws, as well

as European laws, have to be considered (in the case of

Europe). For Germany, the copyright law and the Eu-

ropean directive 96/9/EG are of interest. Both, as well

as different court decisions throughout the years, show

that web scraping is legal for scientific purposes if the

extracted information is not made publicly available

and is not commercialized. Further, the information

has to be freely accessible, without the need for regis-

tration. Even if the terms and conditions of a website

prohibit the use of a web scraper, they only apply if

they have been accepted by a registration.

Since personal information is extracted, data pro-

tection laws have to be considered as well. In Europe,

a deceased person is, by definition, not covered by

the data protection law. Nevertheless, postmortem per-

sonal rights concerning the dignity of the deceased

person still apply. However, for scientific purposes, the

extraction of personal information from data sets is

permitted, as long as they do not include information

about persons alive (L

¨

ower, 2010, 33). In the case of

death notices, this refers to the names (and addresses)

of relatives mentioned.

2.2 Online Newspaper Death Notices

Since the 18th century, the death of persons was an-

nounced publicly. The first death notice in Germany

was published in 1753. But not until the 19th century

the regular publication of death notices was established

(Gr

¨

umer and Helmrich, 1994, 69). The structure of a

death notice is nowadays more or less standardized, as

can be seen in figure 1.

Traditionally, death notifications are published in

newspapers. Increasingly, in many countries, death no-

tices are also published in online newspaper obituaries.

Online death notices have been used as a data source

for research purposes in the US. For example, Boak

et al. (2007) used death notices from the Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette to monitor mortality. When comparing

their extracted death notices to administrative records,

they were able to find death notices for 73.5% of the

registered deceased persons, 31.4% could be found in

registers of surrounding cities, and 8.96% could not be

detected (Boak et al., 2007, 534). Similar results were

reported by Soowamber et al. (2016, 167) when using

death notices to detect panel mortality. Although they

do not report the proportion of detected deaths, they

considered death notices as a valid and reliable data

source (Soowamber et al., 2016, 167).

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

320

s

y

m

b

o

l

opening line

name, title

birthname

date of birth, date of death

grief text

transition

relatives

other notes

Figure 1: Structure of death notifications (based on Gr

¨

umer

and Helmrich, 1994, 66).

Therefore, we decided to study whether death noti-

fications can be used in Germany. In 2017, our search

yielded a total of 152 online newspaper obituaries in

Germany. Five of them were unsuitable for web scrap-

ing since they required prior registering for access.

Since they usually don’t cover deaths in our region of

interest, we don’t consider this exclusion as limiting

our conclusions.

The online newspaper obituaries were divided into

groups of the same layout. With two web scrapers,

we were able to cover 109 of 152 online newspaper

obituaries. For the rest, individual programs would be

needed. Although we covered only about 72% of the

obituaries, we manually verified that none of the online

newspaper obituaries which could not be scraped con-

tained death notifications of our test region. Therefore,

the undercoverage of the scraped data (to be discussed

in section 3) is not due to the exclusion of the remain-

ing 43 obituaries.

The web scraper was written in Python 2.7 using

Scrapy 1.3.3 (Kouzis-Loukas, 2016).

The death notices are segmented on the website.

There is always the name of the deceased person, some-

times followed by the date of birth and date of death,

if available, concluding with a picture of the printed

death notice. Sometimes the websites displayed a small

image of the printed death notice and next to it the

name as well as the first 300 characters of the death no-

tice. All sites offer a filter by names, dates or locations

for searching obituaries.

2.3 Problems

Scraping the obituaries encountered different problems

(for details, see Redlich 2017).

An unexpected problem was due to multiple death

notices per person on the same web page. For some

of those, two pictures of death notices were found in

the same segment of a death notification beneath each

other. Scrapy then concatenated the URLs into one

non-existing URL. Therefore, only the URL of the

first picture in each segment was considered.

The second problem concerned the resolution of

the images. Since only a small preview was shown

in the overview of all death notices, a solution for

accessing the full-size death notice was needed. The

scraper was instructed to search within an URL for

the suffixes “small” or “medium” (depending on the

size of the picture). Hence, the suffixes “small” and

“medium” were replaced by “large” before scraping

the picture.

For some websites, the names of the pictures con-

sisted of a letter-number-combination and the larger

pictures were embedded into JavaScript. Although

scraping data within JavaScript (Mitchell, 2015, 147-

159) is possible in principle, we were unable to find a

working solution within a reasonable time. However,

since those websites provided a medium resolution

picture of the death notice, no records were lost.

Furthermore, Scrapy was often unable to distin-

guish between empty pages, the end of the filtered

search and the end of the database. Sometimes, a plau-

sible date without death notices was found, because

not every day obituaries were published. In those cases,

depending on the title of the page, the web scraper was

instructed to stop extraction for this notification or try

to find information for the day before.

For websites with a 300 letter preview of the death

notice, the date of birth and date of death were not

explicitly stated in the title or subtitle of the segment.

Instead, to extract this information, they had to be part

of the first 300 characters to be scraped. In the case of

multiple dates, e.g. date of funeral, the first two dates

were extracted as the date of birth and date of death.

Two major problems were the modification of the

HTML-code of the website or the modification of the

robots.txt

by the webmaster during our collection

period of two years. When the

robots.txt

is modi-

fied to prevent the extraction of information, web scrap-

ing should not be performed. If the HTML-code is

modified, the program code has to be adjusted, which

can be very time-consuming. We also experienced

changes of the

robots.txt

and of the HTML-code.

While the first did not impact our results, because the

respective online newspaper obituaries did not cover

our test region, the latter caused a time-consuming re-

vision of the programmed web scraper.

Moreover, the image of a death notification could

contain additional information if dates or locations

were missing in the subtitle or within the first 300

characters.

Web Scraping Online Newspaper Death Notices for the Estimation of the Local Number of Deaths

321

Therefore, we tested the use of optical character

recognition and regular expressions to gain this infor-

mation from the extracted bitmaps of the death notifi-

cations. We tested Tesseract and ABBY Fine Reader

(Lawson 2015, 96; Mitchell 2015, 163). Even though

we attempted to get the largest resolution possible the

resolution was not large enough for Tesseract or ABBY

Fine Reader to provide acceptable results (see figures

2 and 3). Especially colored death notices with non-

standard fonts lead to useless OCR outputs. Although

the attempt was made to still extract as much infor-

mation as possible from the given OCR using AWK

(Aho et al., 1988), no working solution could be found.

As seen in figure 2 the letter “e” was recognized as a

“c” and the cross symbol indicating the date of death

was recognized as two characters including a number.

Since non-standard layout and color are in some cases

more expensive, there might be a systematic difference

in socio-economic status of the deceased between OCR

recognizable and not OCR recognizable death notifi-

cations. However, since only a few death notifications

were colored, we don’t consider this as a problematic

exclusion.

Figure 2: Artefacts by OCR using Tesseract (example 1).

Birth name incorrectly identified and cross symbol misclas-

sified as part of numbers. Personal information of relatives

are concealed.

Since the websites may nevertheless provide the

name, date of birth, date of death, and location this

might not necessarily cause biased estimates.

3 RESULTS

We extracted death notices for people in one of the

largest German cities for all deaths for every day in

2015 and 2016. For this, all existing six local online

newspaper obituaries were used. Since the OCR out-

puts were not usable, we only used the embedded text

Figure 3: Artefacts by OCR using Tesseract (example 2).

Color, font and low resolution make OCR impossible. Per-

sonal information of relatives are concealed.

in the HTML. After extraction, the data was cleaned

and preprocessed using R 3.4.0. For missing data on

sex and nationality (German/other), we used a large

administrative database to impute sex and nationality

based on the first name. The results of the scraped data

were compared to the official local death registry. To

test for selectivity of the scraped data, we compared

age, sex, and nationality between scraped data and

administrative data. We conducted two-sample tests

of proportions and means using Stata 15 (StataCorp,

2017).

As shown in table 1, only 3,007 death notices

(21.47%) could be scraped, while the administrative

database contains 14,003 registered deceased persons.

Table 1: Number of deceased persons in each data set.

Administrative Scraped

2015 7,002 1,427

2016 7,001 1,580

∑

14,003 3,007

For sex, the difference between proportions is

3.39% (see table 2) and therefore significant in this

setting (p < 0.01).

Table 2: Number of deceased persons by sex. The adminis-

trative data contains a higher proportion of females.

Administrative Scraped

Female 7,399 1,489

(52.94%) (49.55%)

Male 6,577 1,516

(47.06%) (50.45%)

∑

13,976 3,005

Only 0.77% in the scraped data compared to 2.56%

in the administrative data seem to be foreigners (see

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

322

table 3). This difference of 1.79% is also significant

(p < 0.01).

Table 3: Number of deceased persons by nationality. The ad-

ministrative data contains a higher proportion of foreigners.

Administrative Scraped

German 13,606 2,979

(97.44%) (99.23%)

Other 357 23

(2.56%) (0.77%)

∑

13,963 3,002

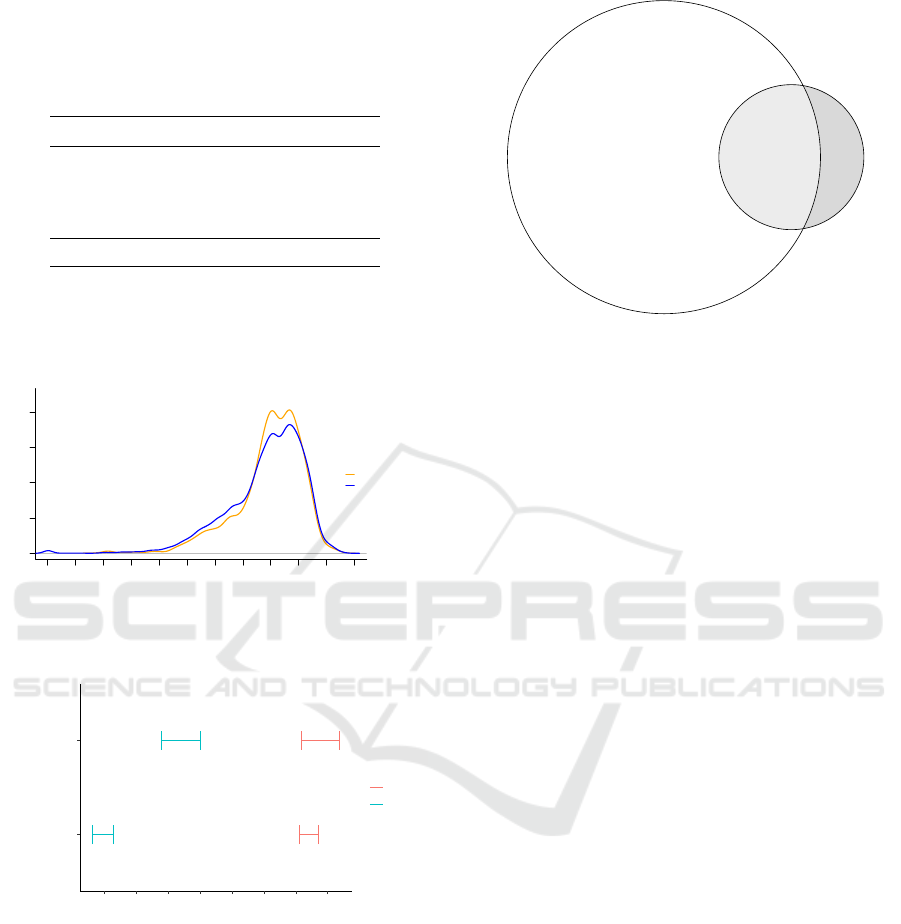

For age at death, we found a higher proportion of

people between 75 and 90 in the scraped data (see

figure 4 and 5).

age

density

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110

0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04

data set

scraped

administrative

Figure 4: Kernel densities of age at death by data set. Scraped

data shows a higher proportion of persons between 75 and

90.

●

●

●

●

administrative

scraped

75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82

age

sex

●

●

female

male

Figure 5: 95%-confidence intervals for age at death condi-

tioned on sex by data set. Mean age for males is higher in

scraped data.

As a result of the different distributions, the mean

age of death differs significantly between the two data

sets (administrative: 78.31; scraped: 79.57;

p < 0.01

).

When comparing age between the datasets by sex, we

found no significant difference for females (adminis-

trative: 81.4; scraped: 81.77;

p = 0.31

), but for males.

Here, the mean age differed significantly (administra-

tive: 74.94; scraped: 77.39; p < 0.01).

The scraped data does not contain any death no-

tices for deceased persons younger than 18 years. By

888

2,116

11,887

6FUDSHG

$GPLQLVWUDWLYH

Figure 6: Overlap of scraped death notifications (

n = 3, 004

)

and administrative data (n = 14, 003).

clerical search, we found that this was because acciden-

tally, for all deaths of people younger than 18, either

date of birth, date of death or the location was missing

in the database. By inquiry, we made sure that this

was not the result of an editorial policy, but merely the

result of randomly missing data in a small sample.

All analyses described above compared adminis-

trative and scraped datasets as aggregated data. To

estimate the probability that a deceased person can be

found in an online obituary, both data sets have to be

linked individually. Different combinations of match-

ing variables (first name, last name, birth name, date

of birth and death) were tested. During the tests, we

compared those records where different rules implied

different matches. The best combination was defined

as the rule which yields the largest amount of true

positives while not leading to false positives. Overall,

the best linkage result was observed by using the full

name, date of birth and date of death, and – if the date

of birth was not available – name and date of death.

During the linkage, three cases with duplicates in

the scraped data were detected. These were due to

multiple death notifications for the same person with

different information. In two cases there were death

notices with and without the second name, and in one

case the prefix of the last name had a typo.

Finally, the overlap of the two datasets (

n = 2116

)

was 17.8% of the administrative data and 70.4% of the

death notifications (see figure 6).

When comparing matched and not-matched per-

sons of the scraped and administrative dataset, not-

matched persons had a significantly higher proportion

of females (53.23 % females vs 46.77 %; p < 0.01).

For nationality, a higher proportion of non-German

persons were among the not-matched cases (2.80%

vs 0.57%;

p < 0.01

). This result might indicate a cul-

tural difference of announcing a persons death through

Web Scraping Online Newspaper Death Notices for the Estimation of the Local Number of Deaths

323

death notices. It should be noted that while the ad-

ministrative dataset contains the factual nationality of

a deceased person, the citizenship of the persons in

the scraped data was derived from the first name. So

we might have misclassified the citizenship of some

deceased persons in the scraped data.

The age of the deceased persons differed for about

one year between matched and not-matched cases,

where the not-matched are younger (78.12 vs 79.77

years); the difference is significant (p < 0.01).

A manual check of a sample of not-matched per-

sons (

n = 20

) used additional information resulting

from intensive web queries for each case. This check

indicated that some problems are due to the location

as a filter. Notifications with missing locations were

excluded by the obituaries during searches. False pos-

itives were prevalent in the scraped data because the

name of the town is not a unique identifier and could

be a substring of other city names. Additional errors

were due to typos in locations, which were missed by

searches in the obituaries. In several cases, the first

name of a deceased person seemed to be wrong al-

though all other identifiers matched. Since there is no

legal requirement that the actual name of the person

has to be used in the death notice nicknames and sec-

ond names were found in the scraped data instead of

the first name.

4 CONCLUSION

Real-world research applications of web scraping are

more complicated than widely believed. If many dif-

ferent websites have to be scraped over an extended

period, the problems resulting from minor changes of

HTML-code and the representation of the data of in-

terest within a web page requires continuous efforts

on updating the scraper.

Furthermore, for our application, the results indi-

cate that the online information available is not a ran-

dom sample of the underlying population. Less than

18% of the registered deceased persons could be found

in the scraped data. We observed lower proportions

of men and foreigners in scraped and administrative

data; therefore the estimation of death rates within

subgroups by using scraped data will yield biased esti-

mates.

For the estimation of death rates, our conclusions

agree with the assessments of scraped data in compar-

ison to administrative data for the estimation of job

vacancies (Swier, 2017): Coverage is incomplete and

does not yield a random sample. Contrary to Boak

et al. (2007) and Soowamber et al. (2016) we conclude

that web scraping online death notices is not a suitable

alternative for the use of administrative data sets. How-

ever, the deviating result may be due to culture-specific

differences in the use of online death notifications be-

tween the countries studied.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the four reviewers for their suggestions to

improve the manuscript. Author contributions: The

idea, design and access to administrative data was due

to RS, who also wrote the final version. Web scraping,

linkage and analysis was done by SR.

REFERENCES

Aho, A. V., Kernighan, B. W., and Weinberger, P. J. (1988).

The AWK Programming Language. Addison Wesley,

Reading.

Barcaroli, G., Fusco, D., Giordano, P., Greco, M., Moretti, V.,

Righi, P., and Scarn

`

o, M. (2016). ISTAT farm register:

Data collection by using web scraping for agritourism

farms. In Modernization of Agricultural Statistics in

Support of the Sustainable Development Agenda: ICAS

VII: Seventh International Conference on Agricultural

Statistics: Rome 26.-28. October 2016, pages 1055–

1062.

Bharanipriya, V. and Kamakshi Prasad, V. (2011). Web

content mining tools: A comparative study. Interna-

tional Journal of Information Technology and Knowl-

edge Management, 4(1):211–215.

Boak, M. B., M’ikanatha, N. M., Day, R. S., and Harrison,

L. H. (2007). Internet death notices as a novel source

of mortality surveillance data. American Journal of

Epidemiology, 167(5):532–539.

Chow, T. E. (2012). “We know who you are and we know

where you live”: A research agenda for web demo-

graphics. In Sui, D., Elwood, S., and Goodchild, M.,

editors, Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge: Vol-

unteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and

Practice, pages 265–285. Springer, Dordrecht.

Gatterbauer, W. (2009). Web harvesting. In Liu, L. and

¨

Ozsu, M. T., editors, Encyclopedia of Database Sys-

tems, pages 3472–3473. Springer, Boston.

Glez-Pe

˜

na, D., Louren

c¸

o, A., L

´

opez-Fern

´

andez, H., Reboiro-

Jato, M., and Fdez-Riverola, F. (2013). Web scraping

technologies in an API world. Briefings in Bioinfor-

matics, 15(5):788–797.

Gr

¨

umer, K.-W. and Helmrich, R. (1994). Die Todesanzeige:

Viel gelesen, jedoch wenig bekannt: Deskription eines

wenig erschlossenen Forschungsmaterials. Historical

Research, 19(1):60–108.

Haddaway, N. R. (2015). The use of web-scraping software

in searching for grey literature. The Grey Journal,

11(3):186–190.

Hoekstra, R., Bosch, O. T., and Harteveld, F. (2010). Au-

tomated data collection from web sources for offical

HEALTHINF 2019 - 12th International Conference on Health Informatics

324

statistics: First experiences. Technical Report 2010-

132-KOO, Statistics Netherlands.

Koster, M. (1993a). About /robots.txt. Accessible un-

der: http://www.robotstxt.org/robotstxt.html [accessed:

21.05.2017].

Koster, M. (1993b). Guidelines for robot writers. Acces-

sible under: http://www.robotstxt.org/guidelines.html

[accessed: 22.06.2017].

Kouzis-Loukas, D. (2016). Learning Scrapy: Learn the Art

of Efficient Web Scraping and Crawling with Python.

Packt Publishing, Birmingham.

Landers, R. N., Brusso, R. C., Cavanaugh, K. J., and Collmus,

A. B. (2016). A primer on theory-driven web scraping:

Automatic extraction of big data from the internet for

use in psychological research. Psychological Methods,

21(4):475–492.

Lawson, R. (2015). Web Scraping with Python: Successfully

scrape data from any website with the power of Python.

Packt Publishing, Birmingham.

Le, Q. T. and Pishva, D. (2015). Application of web scrap-

ing and Google API service to optimize convenience

stores’ distribution. In The IEEE 17th International

Conference on Advanced Communications Technology:

“Named Data Networking – A Future Internet Architec-

ture”. July 1–3, 2015, pages 478–482. IEEE.

L

¨

ower, W. (2010). Grenzen der Erhebung und Verar-

beitung von Sterbedaten durch den (postmortalen)

Pers

¨

onlichkeitsschutz. In Dicke, P. et al., editors, Ein

Nationales Mortalit

¨

atsregister f

¨

ur Deutschland, pages

16–22. RatSWD, Berlin.

Mitchell, R. (2015). Web Scraping with Python: Collect-

ing Data from the Modern Web. O’Reilly Media, Se-

bastopol.

Mpinga, E. K., Delley, V., Jeannot, E., Cohen, J., Chastonay,

P., and Wilson, D. M. (2014). Testing an unconven-

tional mortality information source in the canton of

geneva switzerland. Global Journal of Health Science,

6(1):1–8.

Najork, M. (2009). Web crawler architecture. In Liu, L.

and

¨

Ozsu, M. T., editors, Encyclopedia of Database

Systems, pages 3462–3465. Springer, New York.

Redlich, S. (2017). Web Scraping zur Gewinnung von Test-

daten f

¨

ur administrative Register. Master thesis, Uni-

versity of Duisburg-Essen.

Soowamber, M. L., Granton, J. T., Bavaghar-Zaeimi, F., and

Johnson, S. R. (2016). Online obituaries are a reliable

and valid source of mortality data. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 79:167–168.

StataCorp (2017). Stata: Release 15. Statistical Software.

StataCorp LLC, College Station.

Swier, N. (2017). Web Scraping for Job Vacancy Statistics.

Big Data ESSNet Workshop. Sofia. 24–25 February

2017.

Sylvestre, E., Bouzille, G., Breton, M., Cuggia, M., and

Campillo-Gimenez, B. (2018). Retrieving the vital

status of patients with cancer using online obituaries.

In Ugon, A., Karlsson, D., Klein, G. O., and Moen, A.,

editors, Building Continents of Knowledge in Oceans of

Data: The Future of Co-Created eHealth: Proceedings

of MIE2018, pages 571–575. IOS Press.

Thelwall, M. and Stuart, D. (2006). Web crawling ethics

revisited: Cost, privacy, and denial of service. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and

Technology, 57(13):1771–1779.

van Wel, L. and Royakkers, L. (2004). Ethical issues in

web data mining. Ethics and Information Technology,

6(2):129–140.

Web Scraping Online Newspaper Death Notices for the Estimation of the Local Number of Deaths

325