An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies

Giampaolo Bella

1

, Karen Renaud

2,3

, Diego Sempreboni

4

and Luca Vigan

`

o

4

1

Dipartimento di Informatica, Universit

`

a di Catania, Italy

2

Division of Cybersecurity, University of Abertay Dundee, U.K.

3

University of South Africa, South Africa

4

Department of Informatics, King’s College London, U.K.

Keywords:

Beautiful Security, User Survey, Formal Analysis, Cyber Security.

Abstract:

“Beautiful Security” is a paradigm that requires security ceremonies to contribute to the ‘beauty’ of a user

experience. The underlying assumption is that people are likely to be willing to engage with more beautiful

security ceremonies. It is hoped that such ceremonies will minimise human deviations from the prescribed

interaction, and that security will be improved as a consequence. In this paper, we explain how we went about

deriving beautification principles, and how we tested the efficacy of these by applying them to specific secu-

rity ceremonies. As a first step, we deployed a crowd-sourced platform, using both explicit and metaphorical

questions, to extract general aspects associated with the perception of the beauty of real-world security mech-

anisms. This resulted in the identification of four beautification design guidelines. We used these to beautify

the following existing security ceremonies: Italian voting, user-to-laptop authentication, password setup and

EU premises access. To test the efficacy of our guidelines, we again leveraged crowd-sourcing to determine

whether our “beautified” ceremonies were indeed perceived to be more beautiful than the original ones. The

results of this initial foray into the beautification of security ceremonies delivered promising results, but must

be interpreted carefully.

1 INTRODUCTION

Security measures can trigger unintended and unan-

ticipated side effects if users consider them unattrac-

tive. By unattractive, we mean difficult, arduous, in-

convenient and generally a nuisance. If people per-

ceive their interactions with security systems nega-

tively, instead of something that is there to protect

them and their data, they might try to bypass or game

them (for instance, by using weak passwords). People

will dread an encounter with a system they consider

unattractive. Yet “beauty” is likely to be in the mind

of the beholder, and it is not necessarily obvious how

to beautify security systems.

Bella and Vigan

`

o introduced the beautiful security

approach (Bella and Vigan

`

o, 2015), postulating that

security should:

1. become a primary, inherent feature of the system;

at the same time,

2. not be disjoint from the system functionalities; at

the same time,

3. contribute to the very positive experience that the

user has of the system, ultimately making that ex-

perience beautiful.

While the first two are dealt with elsewhere, the third

is the one that this paper is concerned with: how can

security ceremonies contribute to the positive experi-

ence that a user has of a secured system, ultimately

triggering a perception of beauty?

Because users are an essential and integral part of

the greater socio-technical system, they have to en-

gage with security ceremonies (Ellison, 2007), which

are added to systems in order to secure them.

An example of a ceremony is an access control

system that restricts access to authorised users by re-

quiring the user to identify and authenticate them-

selves.

Users engage in a kind of ‘ritual’ with security cer-

emonies, with predetermined actions being actioned

by the two parties in a prescribed order when they in-

teract with the ceremony. The result may be that inter-

action with the security ceremony is far from straight-

forward. The need to ensure the security of systems

may unintentionally make interaction with security

ceremonies complex (and possibly unattractive).

Bella, G., Renaud, K., Sempreboni, D. and Viganò, L.

An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies.

DOI: 10.5220/0007921501250136

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2019), pages 125-136

ISBN: 978-989-758-378-0

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

125

A number of approaches have been developed to

inform the design and analysis of secure ceremonies,

e.g., (Bella and Coles-Kemp, 2012; Radke et al.,

2011; Karlof et al., 2009; Martina et al., 2015), but

these seem to neglect the notion of beauty. We coin

the term “beautification” to refer to the process of

making security ceremonies (more) beautiful. We

know that beautifying existing ceremonies by merely

simplifying them has sometimes led to the deploy-

ment of insecure ceremonies. Such ceremonies con-

tain vulnerabilities that could be exploited by an at-

tacker. A prime example is the use of fallback ques-

tions to allow people to recover from forgotten pass-

words, but which often serve as a convenient back

door for attackers (Schechter et al., 2009). In sum,

it is known that security ceremonies have functional

goals that guarantee requisite security properties. For

example, a password recovery ceremony must ensure

confidentiality of the replacement password.

This need motivates the need for a methodology

that makes beautiful security practically applicable.

Such a methodology is the main contribution of this

paper. We leveraged crowdsourcing to help us to ori-

ent security ceremony design towards greater beauty.

The methodology was applied, as a proof of concept,

to four real-world security ceremonies aimed, respec-

tively, at voting, logging into a computer, setting up

a password and entering physical premises. Our find-

ings are promising but require careful interpretation,

as we shall explain.

We commence with a brief review of the relevant

literature (§2) and continue by presenting our method-

ology. The first step was to consult crowdsourcing

platform participants using questions aimed at gath-

ering their views on what makes cyber security beau-

tiful (§3). The second step was to leverage such views

to formulate beautifying guidelines to inform the de-

sign of more beautiful ceremonies (§4). The third

step applied the guidelines to existing ceremonies,

attempting to make them more beautiful (§5). The

fourth and final step returns to the crowdsourcing plat-

form participants to determine whether the intended

beautification of the ceremonies was successful (§6).

We draw conclusions and discuss future work in §7.

2 BEAUTY IN SECURITY

Beauty is traditionally thought of as something vi-

sual, but it has also been applied to music (Portanova,

1975), mathematics (Erickson, 2011; Russell, 1956),

truth (Nass et al., 2000) and design (Gelernter, 1998).

Carritt (Carritt, 1932) claims that beauty is not

simply related to the agreeableness or usefulness of

an item or experience. He says that beauty has more

to do with a contemplation of a feeling experienced

during, or remembered after, an encounter with a par-

ticular artefact. Hence, beauty is interwoven with a

person’s experiences.

What characteristics of this experience might con-

tribute to beauty? The literature suggests the fol-

lowing: ease of use (fluency) (Reber et al., 2004),

a sense of pleasure (Tatarkiewicz, 2006), simplicity

(Chen et al., 2005; Karvonen, 2000; Glynn, 2010),

aptness (Gelernter, 1998), elegance (Gelernter, 1998),

the value of the system in a given context (goodness)

(Hassenzahl and Monk, 2010) and responsiveness

(Pancake, 2001). This review suggests that beauty

will be attributed to an artefact if it elicits positive

feelings, based on prior user experiences.

Let us now consider the idea of beautiful secu-

rity software. This is especially important because

its non-use or, worse, a negative experience of an

unattractive ceremony, will compromise security and

leave holes open for hackers to exploit. Current

experiences of common security software appear to

confirm their general unattractiveness (Cranor and

Garfinkel, 2005; Sheng et al., 2006; Clark et al.,

2011). The consequence is that users might act to

circumvent the ritual (Blythe et al., 2013). Aware-

ness and training programmes are the standard or-

ganisational response to this (Yildirim, 2016), but

the effectiveness of such drives is patchy (Banfield,

2016; Kennedy and Kennedy, 2016). Training does

not work because it can not overcome a reluctance

that stems from previous negative experiences with

unattractive software.

What we are proposing is to beautify security cer-

emonies so that people will want to use them because

the beauty thereof results in positive feelings. What

we seek to discover is exactly how to achieve this. In

summary, we want to build security ceremonies that

users will want to engage with because doing so has

been a positive experience. This might mean that the

software displays one or more of the general charac-

teristics listed above. It could also be that beautiful

security ceremonies have their own set of characteris-

tics: identifying these is the topic of this paper.

3 CROWDSOURCING FOR THE

CONCEPT OF BEAUTIFUL

SECURITY

Bella and Vigan

`

o (Bella and Vigan

`

o, 2015) asked a

fundamental question: what constitutes a beautiful

user experience of a security ceremony? Answer-

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

126

ing this question is far from trivial both because of

the vastness of the spectrum of possible answers and

because, as researchers working in security, our own

point of view is likely to be biased. For these reasons,

we decided to source an answer to this question from

a heterogeneous global crowd of people by means of

a questionnaire.

Our questionnaire aimed to gain an understand-

ing of how the users of security ceremonies perceive

and describe them by means of a scale of “emotional”

values, leaving them free to express as many values as

they desired. In other words, we designed the ques-

tionnaire to explore a correlation between security

ceremonies and how their beauty is sensed. The ques-

tionnaire consisted of the following four questions:

Q1 Think about when you log into your bank account,

and you use one of those little devices the bank

sends you that displays a number for you to enter

as your password. Do you consider this process to

be: Fun, Beautiful, Excessive, Annoying, Engag-

ing, Essential, Reassuring, Appealing?

Q2 When you were a child, did you ever read a

book about a group of children having a secret

club, with meetings where people were allowed in

when they knew the secret password? In this case,

how would you rate the security of this process

in terms of: Fun, Beautiful, Excessive, Annoying,

Engaging, Essential, Reassuring, Appealing?

Q3 Think about a web-based system that requires you

to provide a password that meets certain rules

(e.g., upper case, lower case, digit, special char-

acter, minimum length). In this case, how would

you rate the security in terms of: Fun, Beautiful,

Excessive, Annoying, Engaging, Essential, Reas-

suring, Appealing?

Q4 Think about old-fashioned burglar alarms that

used to go off every time a bird landed on the roof,

or lightning struck nearby. The only way to cor-

rect a false alarm was to get home as quickly as

possible to enter the PIN to shut it up. Modern

systems are different. They are often controlled

from your smartphone. Now you can keep an eye

on them from wherever you are in the world, and

even see if everything at home is in order, by link-

ing to cameras in your home. False alarms can

quickly and easily be dealt with, without annoying

your neighbours for hours on end. This is an ex-

ample of how physical security has become more

engaging. Can you think of a way that cyber se-

curity could improve in the same way?

The first three questions were closed-ended, al-

lowing people to respond with multiple preferences

(and thus allowing us to gain insights into their feel-

ings, where these could not be represented by only

one choice). The final question was open-ended. The

rationale behind the questions is as follows.

3.1 Q1 — Token Device

The first question concerns the technology that people

use to confirm their identity upon login to their own

online bank accounts. Originally, when a customer

activated the e-banking functionalities on their bank

account the bank would supply them with a plastic

card or a sheet of paper with several one-time pass-

words (OTPs) to enable them to carry out two-factor

authentication

1

, in this case using their username-

password pair as well as a OTP. More recently, banks

started handing out small electronic devices to their

customers that are capable of generating an OTP on

the fly, instead of their having to consult a pre-printed

list of fixed OTPs. Nowadays, these devices are very

common

2

.

We devised the first question to explore reactions

to OTPs as a mechanism that is widely used to pre-

vent bank-account hacking but that is sometimes not

as usable as it should be (Subashini and Sumithra,

2014). OTP devices are intended to help users to

handle a situation in which security ought to be the

first goal, even though the way it achieves this might

not be ideal. We wanted to find out what respondents

thought about needing to possess such a physical de-

vice to generate OTPs. This question allowed us to

gather evidence to understand whether current two-

factor authentication ceremonies are in line with our

ideas or whether we ought to start thinking about al-

ternative approaches.

3.2 Q2 — Secret Club

The second question is about using an episode of the

British pre-school animated television series “Peppa

Pig” (Bella and Vigan

`

o, 2015). In this episode, ti-

tled “The Secret Club”, Peppa’s friend Suzy Sheep is

1

Two-factor authentication asks the user who wishes to

be authenticated to provide two different secrets: something

the user knows (e.g., a password), something the user has

(e.g., a device), something the user is (e.g., unique biomet-

ric features such as fingerprints or the patterns on a per-

son’s retina blood vessels). This can be straightforwardly

extended to multi-factor authentication, where the user has

to provide multiple different authentication factors.

2

In fact, mobile applications have been developed to en-

able users to generate OTPs on their smartphones, thus re-

placing also these small electronic devices. However, given

that these mobile applications are not yet widespread (only

some countries and some banks have adopted them so far),

we decided not to include this option in our questionnaire.

An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies

127

building a secret club whose membership is identified

by wearing a mask. Joining the club demands utter-

ing a one-time password, as shown by the following

excerpt:

Peppa: Hello, Suzy.

Suzy: Hello, Peppa.

Peppa: Why have you got that mask on your face?

Suzy: So people don’t know it’s me. I’m in a

secret club.

Peppa: Wow! Can I be in your secret club?

Suzy: Shh! It’s not easy to get into. You have to

say the secret word.

Peppa: What word?

Suzy: Blaba double!

Peppa: Blaba double!

Suzy: Right, you’re in.

Later on Suzy will comment that the password

changes all the time to keep it secret! It would ap-

pear that anything related to secrecy is perceived to

be an enjoyable game, even before the rules are set,

and Bella and Vigan

`

o use this to propose that a user’s

experience of a security ceremony could be appeal-

ing and beautiful as is demonstrated by the childish

enthusiasm with which Peppa reacts in this episode.

What would our respondents think of a similar sit-

uation? Even though it could seem a fairly childish

example, we devised the second question to help the

respondents connect with similar experiences from

their own childhoods, thereby allowing us to deter-

mine whether the respondents agreed with Bella and

Vigan

`

o’s assessment of the attractiveness of this ex-

ample. Thus, this second question aimed to give us a

reference point for the kind of user experience that we

would like to achieve when security is seen in terms

of beauty and attractiveness.

3.3 Q3 — Password Creation

Given that the second question considered passwords

in a childish context, we devised the subsequent ques-

tion to ask about passwords in a more adult context,

thus also allowing us to check whether the answers

obtained would be in line with those given in response

to Q2. More specifically, Q3 considers a thorny situa-

tion that users have to face at least once a day. A cloud

service, an email account, a favourite e-commerce

website, or maybe a laptop account, all require the

user to enter a secret password correctly to gain ac-

cess. Nowadays, this usually requires a strong pass-

word that respects certain criteria (such as a minimum

length, different characters, special characters) and is

also semantically different from the user’s sensitive

information (such as name or birth date). We asked

respondents to express how they felt about engaging

with this particular security ceremony. We expected

to obtain results that would reflect the users’ frustra-

tion with current password management systems.

3.4 Q4 — Cyber Security Improvement

We chose to conclude with an open question to cap-

ture the respondents’ different points of view. Cyber

security will continue to evolve and we believe that

this evolution could take many different directions.

We devised the final question to collect a wide va-

riety of suggestions about the different ways of mak-

ing security ceremonies more attractive, and thus of

pursuing beauty. By using an analogy with an old-

fashioned burglar alarm, we asked respondents to as-

sess the attractiveness of modern solutions and to pro-

pose improvements related to cyber security.

3.5 Findings

We administered the questionnaire to one hundred re-

spondents. We used the CrowdFlower platform and

did not constrain respondents in terms of language or

geography. CrowdFlower workers span the globe so

we were assured of a heterogeneous sample. The re-

sults for the first three questions are summarised in

Figure 1, whereas Table 1 shows the results of the an-

swers to Q4.

Fun

Beautiful Excessive Annoying Engaging Essential Reassuring Appealing

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

n

o

of preferences

Q1: Token

Q2: Secret

Q3: Password

Figure 1: The answers to questions Q1, Q2 and Q3.

3.5.1 Findings from Q1, Q2 and Q3

The answers to Q1 show that users most often per-

ceive these kinds of ceremonies to be Essential (48)

and Reassuring (41). The third most popular reaction

is that engaging with the ceremony is Annoying (20),

confirming that users find it frustrating. The least cho-

sen options are: Fun (5), Appealing (4) and Beautiful

(2). This reinforces our initial assertions about the

unattractiveness of current security ceremonies.

In Q2, users largely chose Fun (66), followed by

Engaging (19) and Beautiful (12), and finally Annoy-

ing (7) and Excessive (6). This could mean that the

users see that the situation is less serious but also that

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

128

they perceive this to be less burdensome than rigorous

security ceremonies. This is so even though the secret

mentioned in the cartoon is very similar to an actual

password.

In Q3, we can observe similar responses to Q1.

We obtained a high number of preferences for Essen-

tial (46) and Reassuring(42), reflecting the fact that

users sense the importance of a tangible feeling of

reassurance. Similar to Q1, the third most voted re-

sponse is Annoying (23) followed by Excessive (16).

Very few respondents considered the password man-

agement to be Fun (2) or Beautiful (5).

What we can understand from the responses is that

the respondents seem to grasp the Essential nature of

security ceremonies, and they also feel Reassured by

security measures such as passwords and mobile to-

kens. However, they undoubtedly feel annoyed and

consider the security measures Excessive, especially

for password-like ceremonies. The burden of having

external devices such as token generators or compli-

cated passwords could be responsible for the number

of Annoying responses. In designing more beautiful

security ceremonies we have to take this into account.

If we focus on the Fun and Beautiful aspects, we

can see that a majority of the users believe that hav-

ing a secret code in a childish context is funny but

also beautiful and Engaging, as compared to the other

two contexts. In Q2, we did not mention details like

the complexity of the secret but, even so, the per-

ceived positivity of this Peppa Pig experience reveals

the negativity of existing real-life security measures.

If we return to what Carritt (Carritt, 1932) says,

these negative experiences and perceptions will lead

to users not considering the engagement with security

ceremonies to be “beautiful”.

3.5.2 Findings from Q4

In Q4, we analysed the 100 open-ended question re-

sponses. From an open-ended question we expected

several possible kinds of answer, which we had not

only to check but also to classify. In questions like

this, some respondents just provide a random answer

as they are not interested, or are too lazy, to think and

provide a meaningful answer. Our analysis approach

was the following. First of all, we skimmed the list for

yes/no/I-don’t-know answers, removing 27 answers.

After that, we removed 32 answers that we deemed

to be out of context (e.g., due to apparent misunder-

standings). We classified and grouped the 41 remain-

ing answers based on the general idea or suggestions

that they communicated.

The results are shown in Table 1. The general

categories that emerged from the analysis are: SMS,

Geolocation, Biometric, Alert and Password. SMS

suggests to use text messages to warn the users that

something is happening. Geolocation suggests to use

the GPS position or Wi-Fi location to prove that some

operations are allowed from the place where they are

executed. Biometric suggests the use of fingerprint or

face recognition, or other biometric-recognition tech-

nology to authenticate the users. Alert suggests the

use of some kind of notification (e.g., push notifica-

tions) to alert the users. Password suggests that pass-

words be used, but that they be improved in different

ways (e.g., reducing the number of characters, relax-

ing some of the constraints on character type, or the

“distance” from the previous password).

Table 1: Categories for the answers to question Q4.

SMS Location Biometric Alert Passwd

7 2 17 8 7

Biometric technology was suggested by 17 re-

spondents as a viable way to beautify the security ex-

perience, thanks in particular to the recent spread of

fingerprint and face recognition facilitated by smart-

phone manufacturers. 8 respondents expressed the

will to improve cyber security by using some kind of

alerting system through notifications, as long as this is

integrated into a two-factor or multi-factor authentica-

tion solution with multiple devices enabled to receive

warnings.

New methods based on passwords and SMS-

enabled technology were indicated by seven respon-

dents. Finally, two respondents suggested using ge-

olocation as a method that checks the position of de-

vices to authorise certain operations.

4 OPERATIONALISING THE

FINDINGS

The idea behind the questionnaire was to understand

how people characterise the beauty of security cere-

monies in such a way that we could formulate general

guidelines to inform the design of beautiful security

ceremonies, or of beautified versions of existing secu-

rity ceremonies. The previous Section presented the

answers to our questionnaire and reported the insights

we gained. Such insights can be generalised as a va-

riety of guidelines. Here we report the four that we

deem most relevant. They derive from the four ques-

tions seen above, respectively.

G1. Feel unencumbered: you do not need to carry

anything along.

G2. Leverage the sense of the group.

G3. Simplify the rules, even though they seem essen-

tial.

An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies

129

G4. Use biometrics techniques.

G1 enhances the sense of freedom and it comes

from the the insights originated from Q1. At some

point, security analysts ruled that “possessing” some-

thing enables us to pursue security through what we

hold. This changed the pre-existing password ap-

proach due to the perception that holding something is

easier than remembering complicated password. Un-

fortunately, this is not always true. Human nature

makes us prone to forgetting seldom-used objects and

we also easily lose small objects. Cards and one-time

token generators are good examples of objects that are

easily lost or mislaid.

However, a ceremony that asks a user to prove that

they hold an object might not be the best solution to

the perceived unattractiveness of existing security cer-

emonies. The need to possess an essential security

ceremony object could easily be considered burden-

some. It can lead to frustration each time a user can-

not engage with it. This is why we advance guideline

G1 as a solution to this burden every time a person

needs to demonstrate ownership of a physical object.

G2, which derives from the insights for Q2, is

oriented at a ceremony design that makes the user

feel part of a group. This situation is well repre-

sented in the Peppa Pig episode (Peppa, 2010) where

having a secret word implies being part of a secret

club. This view was supported by the responses that

we obtained in the questionnaire because the situ-

ation we described was perceived as being Fun by

most respondents. Although it would seem unusual

to achieve this level of agreement in a such diverse

context, we want to strive towards exciting that same

feeling of enthusiasm when people interact with sys-

tems securely.

G3, stemming from Q3, is a reasonable assump-

tion based on the fact that having simpler ceremony

rules improves the user’s experience while preserv-

ing security. What G3 advances is an approach that

urges a return to simpler rules, thereby freeing the

users from any extra burdens in the execution of es-

sential security ceremonies. Einstein famously said

that things should be “made as simple as possible, but

no simpler”. This applies admirably to our security

context.

G4 suggests using “something you are” in secu-

rity ceremonies. The answers to Q1 and Q3 revealed

that users considered “something you know”, such as

a password, as well as “something you have” burden-

some. An alternative approach that might be more

acceptable could be the use of biometrics, as high-

lighted in the responses to Q4. Although the use of

biometrics is not exempt from critique as many users

(and some developers of security solutions) are con-

cerned about their privacy ramifications, a variety of

different biometrics are available and they do appear

to represent a reasonable compromise, also convey-

ing a sense of play and of being “cool and modern” in

achieving security.

If we are able to introduce G4 in ceremonies, we

will likely obtain a positive response from the users.

5 APPLYING BEAUTIFYING

GUIDELINES

Figure 2: The current Italian voting ceremony.

Figure 3: Potentially beautified Italian voting ceremony.

Bella and Vigan

`

o (Bella and Vigan

`

o, 2015) high-

lighted the crucial aspects of security ceremonies to

acknowledge the value of beautifying ceremonies.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

130

Developers can avoid their ceremony becoming inef-

fective when people bypass it due to its unattractive-

ness. However, achieving cyber security requires sys-

tems to interact with many other pre-existing systems’

ceremonies. Some of these are so part-and-parcel of

others’ systems that it might be difficult to replace

them with more beautiful ceremonies built following

our guidelines. We are concerned with the possibil-

ity of improving an existing security system with as

little effort as possible. Our intention is (i) to take a

system that does not reflect the beautiful security ap-

proach (Bella and Vigan

`

o, 2015) yet it is secure in the

(often) optimistic assumption that the users will use

it precisely as intended by the system designers, and

(ii) to beautify the system following our guidelines so

that this assumption becomes less optimistic and more

realistic.

We consider four ceremonies that are, we believe,

in dire need of beautification:

1. the Italian voting ceremony,

2. the Laptop login ceremony,

3. the Password setup ceremony, and

4. the EU Premises access ceremony.

We discuss ways to make such ceremonies more

beautiful and for each of them we present a specific

beautified version that we have devised, with the ex-

ception of the improved Laptop login ceremony that

has already been developed by Apple.

The beautification changes that we propose reflect

the guidelines we identified in the previous Section

(and also reflect the authors’ combined experience of

designing Socio-Technical Systems). In the following

Section, we will then report on the second question-

naire that we issued to assess whether the new ver-

sions of the security ceremonies that we present here

are indeed perceived to have been beautified.

5.1 Italian Voting Ceremony

Figure 2 shows the voting ceremony currently used

in elections in Italy. Here, and in the following, we

represent security ceremonies by means of Message

Sequence Charts (MSCs), which show the messages

exchanged by the principals (agents) participating in

the ceremony, as well as the internal computation

that is performed by the principals. The MSCs that

we consider in this paper are, hopefully, quite self-

explanatory.

In the Italian ceremony in Figure 2, there are only

two principals: a user (the voter) and an employee of

the polling station (the voting officer). This ceremony

could be considered outdated in comparison with the

voting ceremonies adopted in other countries. The

Figure 4: votingCard cur-

rently used in Italian elec-

tions.

Figure 5: A successful

MacBook login by Apple

Watch.

outdated part of the ceremony would be represented

by the need of the voter to have two different docu-

ments:

1. a national ID card (or any other identification doc-

ument such as a passport or a driving licence) and

2. a votingCard, issued by the city hall to record that

a voter has cast a vote in this election.

This votingCard, which is shown in Figure 4, rep-

resents the ceremony’s main sticking point for two

primary reasons. Firstly, votingCards are stamped at

each election, and they fill up. If this happens, there

are no more spaces for the voting officer to stamp the

votingCard to register the voter’s presence. A second

problem occurs when a voter loses their votingCard.

In both cases, the voter will first need to obtain a new

votingCard from official sources at the city hall in or-

der to be able to vote in this election (and some of the

following ones, until the new votingCard is full).

During electoral rounds in the last years, these

two issues have created particularly obvious difficul-

ties, with long queues snaking out of city hall offices

across Italy, populated by voters needing to obtain

new copies of their votingCards.

The complication comes from the use of a sin-

gle document (the votingCard) for two different pur-

poses: (1) a voting register and (2) an eligibility

proof. Voters experience frustration, especially if the

votingCard’s spaces have been filled up, in which

case the votingCard only satisfies one of its two pur-

poses: eligibility. Recrafting this ceremony offers us

a clear-cut opportunity for improvement.

The new ceremony in Figure 3 applies what we

have suggested with G1 and G3, essentially simpli-

fying the actual ceremony. We suggest replacing the

“what you hold” object (the votingCard in this case).

The simplest way to replace the votingCard would

be to use a system that needs the voter only to present

their national ID card (or identification document),

in its electronic form. The polling station employee

would check the voter’s eligibility and record their

presence in a centralised database, by interacting on-

line with a third principal in the ceremony (the “sys-

tem”). The voter would no longer need to “hold” the

votingCard that causes all the problems stated earlier.

An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies

131

5.2 Laptop Login Ceremony

Every day, users have to enter multiple passwords into

their laptops (and computers). These passwords are

becoming longer and more complex over time due to

the security requirements enforced by operating sys-

tems. Figure 6 shows “password entry”, the login

ceremony currently enforced by most laptop models.

We can of course all agree that passwords are essen-

tial, but our questionnaire respondents confirmed our

personal intuition (and our personal experience) that

users increasingly dread this ceremony.

To simplify the login, Apple has developed a new

way to login on its latest laptops by means of its Ap-

ple Watch product.

3

It is coherent with our guideline

G2 if we see the Apple Watch as a distinctive feature

of a group. This authentication method is incorpo-

rated in the beautified ceremony shown in Figure 7.

Every time the user needs to wake up her MacBook,

she just needs to press a key on the keyboard or touch

the trackpad; after that, the system looks for a paired

Apple Watch and if it finds one, the MacBook unlocks

itself without requesting any other actions. A success-

ful outcome is demonstrated in Figure 5. Similar cer-

emonies using one or more small portable/wearable

devices have also been proposed (Stajano, 2011).

Figure 6: The widespread Laptop login ceremony.

5.3 Password Setup Ceremony

In 2003, the National Institute of Standards and Tech-

nology, published the NIST Special Publication 800-

63 (Burr et al., 2004), where they suggested that users

protect their accounts by inventing “awkward”, new

3

Google and Microsoft are similarly planning to remove

passwords using the protocol Fido in conjunction with An-

droid phones or physical tokens, respectively.

Figure 7: A potentially beautified Laptop login ceremony

(by Apple Watch).

passwords that include uppercase and lowercase let-

ters, numbers and special characters, and by chang-

ing their password regularly. Such passwords aim to

be less guessable (e.g., more resistant to dictionary

attacks). Nowadays, this is common practice, with

websites and services forcing users to craft passwords

respecting these constraints. Figure 8 shows a cere-

mony that reflects this practice.

In 2017, Bill Burr, the person who originally pro-

posed the rules, declared that he regretted publishing

those strict rules (McMillan, 2017). In fact, the new

NIST document published in June 2017 (Grassi et al.,

2017, Section 5.1.1.1) contains the following novel

guidelines:

“...memorized secrets shall be at least 8 char-

acters in length if chosen by the subscriber.

Memorized secrets chosen randomly by the

Credential Service Provider (CSP) or verifier

shall be at least 6 characters in length and

may be entirely numeric. If the CSP or verifier

disallows a chosen memorized secret based

on its appearance on a blacklist of compro-

mised values, the subscriber shall be required

to choose a different memorized secret. No

other complexity requirements for memorized

secrets should be imposed.”

Applying these guidelines, it is possible to propose a

new ceremony that allows users to choose whatever

password they want, morphing the security compo-

nent into a check on the number of times a password is

typed incorrectly. By doing so, we simplify the rules

imposed by the ceremony as suggested by G3. Fig-

ure 9 shows the new “Password setup” ceremony that

we propose.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

132

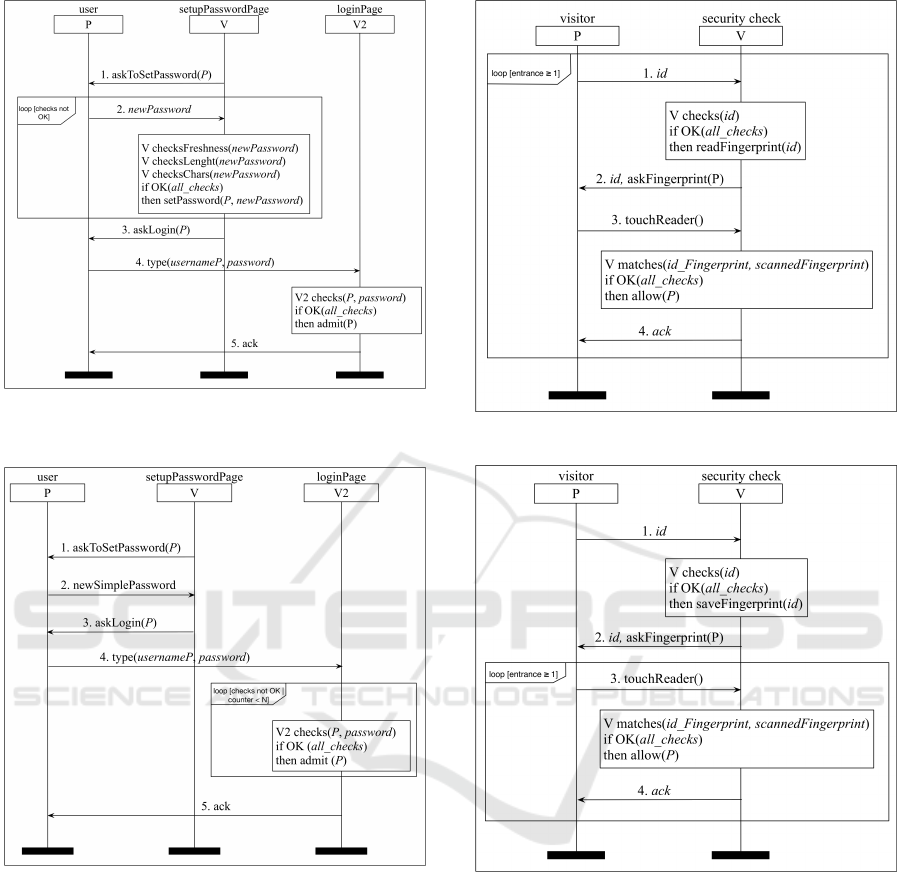

Figure 8: The current Password setup ceremony (using

NIST 2003 rules).

Figure 9: A potentially beautified Password setup ceremony

(using the new NIST rules).

5.4 EU Premises Access Ceremony

Those wishing to gain access to highly-secure build-

ings, such as some EU premises, have to engage with

an authentication ceremony like the one shown in Fig-

ure 10, in which the security staff check both a visi-

tor’s photo-ID (e.g., a national ID card or a passport)

and their fingerprint, which is stored in a database.

This ceremony thus requires a first-time visitor to

engage in a time-consuming fingerprint-registration

process. This ceremony is repetitive in the case of re-

turning visitors, hence especially frustrating if a per-

son needs to access the premises, for example, multi-

Figure 10: The current EU premises access ceremony.

Figure 11: A potentially beautified EU premises access cer-

emony.

ple times a day.

We can apply G4 to make the ceremony (more)

beautiful. Still using biometric technology, it is possi-

ble to devise a leaner ceremony that requires the user

to engage with fewer interactions. In this beautified

ceremony, shown in Figure 11, we have removed the

document check for the entrances after the first one,

so that the main security checks are only addressed by

means of fingerprint control.

An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies

133

6 CROWDSOURCING FOR THE

APPLICATION OF BEAUTIFUL

SECURITY

Our second questionnaire aimed to determine whether

applying our guidelines to ceremonies, or highlight-

ing improvements based on our guidelines in existing

ceremonies, had been effective. We wanted to find

out whether the beautified alternative we present to

the respondents is indeed considered a positive im-

provement, or not.

6.1 Design of the Second Questionnaire

We designed the questionnaire to present two alterna-

tive versions of the same ceremony: an original and

a beautified one, the latter arrived at by applying one

or more of the beautification guidelines. To that end,

we presented respondents with the four different cere-

monies we described in Section 5. Respondents were

asked to answer by giving a preference on which of

the two versions of each ceremony they think is the

most beautiful.

The questionnaire consisted of the following four

closed-ended questions, allowing people to respond

with a single preference:

Q1: You have to choose a new system to be authenti-

cated to vote in an election. Which of the following

two alternative systems is more beautiful?

1. A system that requires you to bring your “vot-

ing eligibility certificate” in addition to your ID

Card.

2. A system that requires you to bring only an elec-

tronic ID document.

Q2: You have to choose a new system to log in on

your laptop. Which of the following two alternative

systems is more beautiful?

1. A system that requires you to type in your pass-

word.

2. A system that requires you to approach your lap-

top with your smart watch.

Q3: You have to choose a new authentication system.

Which of the following two alternative systems is

more beautiful?

1. A system that requires you to insert a complex

password (including requirements such as mini-

mum number of characters, or the use of capital

letters, numbers and special characters).

2. A system that requires you to insert whatever

password you want but it limits the number of

times you may type the password incorrectly be-

fore getting locked out.

Q4: The security officers at the entrance of a secure

building have registered your ID and fingerprint on

the system once you have completed the registra-

tion. Which of the following two alternatives to

access the building from now on is more beautiful?

1. ID + fingerprint every time.

2. Fingerprint every time.

Q1 thus refers to the two versions of the Italian voting

ceremony; Q2 to the two versions of the Laptop login

ceremony; Q3 to the two versions of the Password

setup ceremony; Q4 to the two versions of the EU

Premises access ceremony.

6.2 Findings

We administered the questionnaire to one hundred re-

spondents using the CrowdFlower platform, not con-

straining respondents in terms of language or geogra-

phy. As we remarked above, CrowdFlower workers

span the globe, so we were assured of a heteroge-

neous sample. In order to obtain more focused an-

swers from semi-expert respondents, we also admin-

istered the questionnaire to 24 students of the “Cryp-

tography and Information Security” course that one

of the authors is teaching. The students attending this

module are computer science or mathematics students

in the final year of their undergraduate studies or in

the first year of their master’s studies. We can thus

call these respondents “security-savvy”, in contrast to

the “generic” respondents on CrowdFlower. Security-

savvy respondents were asked the same questions

Q1–Q4 but were also shown the MSCs of the cere-

monies.

The combined results of the second questionnaire

are shown in Figure 12 and we now wish to take stock

and reflect on the responses that we received. The

respondents provided us with extremely useful, and

to some extent slightly surprising, feedback.

Figure 12: Data obtained from the second crowdsourcing.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

134

The answers to the first question clearly indicate

that both generic and security-savvy users find the

beautified Italian voting ceremony that we propose

to be considerably more beautiful than the ceremony

currently in use.

The answers to the fourth question indicate even

more strongly that both generic and security-savvy

users find the novel EU Premises access ceremony

that we propose to be considerably more beautiful

than the ceremony currently in use.

Our respondents were almost equally split be-

tween the original versions of the second and third

ceremonies we considered and their beautified ver-

sions. It is, however, instructive to analyse the re-

sponses in more detail.

Consider the password setup ceremony. It is in-

teresting to note that the 100 generic respondents

have a minimal preference for the proposed beau-

tified ceremony that uses the new NIST rules (51

vs. 49), whereas almost 60% of the semi-expert stu-

dents would rather engage in the original ceremony

based on the 2003 NIST rules. We believe that these

results are evidence to the fact that the respondents,

especially the security-savvy ones, perceived the orig-

inal ceremony to be more robust than the newly pro-

posed ceremony, although the latter is potentially

more lean and beautiful.

Finally, consider the laptop login ceremony. In

this case, 54% of the generic respondents preferred

the original ceremony, whereas 62.5% of the security-

savvy respondents preferred the novel ceremony us-

ing the smart watch. We believe that this indi-

cates that young computer-science/mathematics stu-

dents are more likely to embrace novel technologies

than the cohort of generic respondents, which in-

cludes people of different age, education and back-

ground, who are thus more likely to meet such tech-

nologies with suspicion or even rejection (perhaps

also due to the elitist nature of such technologies).

7 CONCLUDING REMARKS AND

FUTURE WORK

This paper described how we went about finding a

way to beautify security ceremonies, thereby making

beautiful security achievable in practice. We first ex-

plored the literature to find out what beauty means to

users, specifically in the context of interaction with

software systems. We then explored general percep-

tions of security ceremonies by posing questions to

crowdsourcing respondents. Having gained insights

from this process, we proceeded to “beautify” four

security ceremonies. We then posed another round of

questions to crowdsourced participants to judge the

success of our beautification of ceremonies. Overall,

the outcome of the final stage confirmed that two of

the four beautified ceremonies were indeed perceived

to be more beautiful than they had previously been.

The other two beautified ceremonies were not per-

ceived to be more beautiful by our respondents.

The use of crowdsourcing enabled us to explore

and implement the “beautiful” security paradigm,

and gain feedback from a diverse and global audi-

ence. Our experiments confirmed that security cer-

emony design has plenty of scope to consider in-

stilling beauty — with the general aim of achieving

more beautiful security ceremonies. The assump-

tion that people are normally attracted to beauty, as

vastly substantiated by the relevant literature, will

then strengthen such a design because it will be se-

cure not just in isolation but when used by its users.

Beauty may reinforce the designers’ assumptions that

the users will conform to the ceremony as intended.

A variety of real-world ceremonies would bene-

fit from being subjected to a beautification process

based on guidelines such as those proposed here. The

process itself could be developed further, for example

by combining and leveraging several guidelines at the

same time. This will be particularly important in the

case of ceremonies such as Password setup, on which

our experiments showed that beauty will also need

to convey robustness. The Laptop login ceremony,

where newer technologies such as the Apple Watch

are used, might not yet be considered to be beautiful

by the wider population today.

The methodology discussed here has reached the

development stage of a proof of concept but we are

aware that it must be developed further. For instance,

we plan to repeat the crowdsourcing experiments over

a larger sample population to reinforce the actual

beautification guidelines as well as the confirmation

that the beatification has succeeded.

Moreover, although beautifying existing cere-

monies may sometimes lead to simplifying them, sim-

plicity did not turn up in the categories that emerged

from the analysis of answers to open question Q4.

Arguably, simplifying a security ceremony might

compromise security; we thus also plan to develop

combinations of empirical, analytical and formal ap-

proaches (Bella and Coles-Kemp, 2012; Radke et al.,

2011; Karlof et al., 2009; Martina et al., 2015) to help

ensure that when the new paradigm is applied to a

ceremony, possibly simplifying it, it remains secure.

This will require defining degrees of ceremony attrac-

tiveness for humans in a formal, logico-mathematical

way, in order to then be able to reason about the inter-

play of beautification and security, ultimately ensur-

An Investigation into the “Beautification” of Security Ceremonies

135

ing that the beauty of a ceremony does not come at

the expense of its security (which might be the case

for some of the ceremonies we considered, e.g., if

users choose weak passwords), but instead provably

reinforces its security. We expect that this will ulti-

mately lead to defining criteria that formalise when

beautification preserves or reinforces security.

REFERENCES

Banfield, J. M. (2016). A Study of Information Security

Awareness Program Effectiveness in Predicting End-

User Security Behavior. PhD thesis, Eastern Michigan

University.

Bella, G. and Coles-Kemp, L. (2012). Layered analysis of

security ceremonies. In 27th IFIP TC 11 Informa-

tion Security and Privacy Conference, pages 273–286.

Springer.

Bella, G. and Vigan

`

o, L. (2015). Security is Beautiful.

In Security Protocols XXIII, Revised Selected Papers,

LNCS 9379, pages 247–250. Springer.

Blythe, J., Koppel, R., and Smith, S. W. (2013). Circum-

vention of security: Good users do bad things. IEEE

Security & Privacy, 11(5):80–83.

Burr, W. E., Dodson, D. F., and Polk, W. T. (2004). NIST

special publication 800-63. Electronic Authentication

Guideline https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/.

Carritt, E. F. (1932). What is Beauty? Clarendon Press.

Chen, J., Kanj, I. A., and Xia, G. (2005). Simplicity

is beauty: Improved upper bounds for vertex cover.

Manuscript communicated by email.

Clark, S., Goodspeed, T., Metzger, P., Wasserman, Z., Xu,

K., and Blaze, M. (2011). Why (Special Agent)

Johnny (Still) Can’t Encrypt: A Security Analysis of

the APCO Project 25 Two-Way Radio System. In

USENIX Security Symposium, pages 8–12.

Cranor, L. F. and Garfinkel, S. (2005). Security and us-

ability: designing secure systems that people can use.

O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Ellison, C. M. (2007). Ceremony design and analysis. IACR

Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2007:399.

Erickson, M. (2011). Beautiful Mathematics. The Mathe-

matical Association of America.

Gelernter, D. H. (1998). Machine Beauty: Elegance and the

Heart of Technology. Perseus Books, L.L.C.

Glynn, I. (2010). Elegance in science: the beauty of sim-

plicity. Oxford University Press.

Grassi, P. A., Fenton, J. L., Newton, E. M., Perlner,

R. A., Regenscheid, A. R., Burr, W. E., and Richer,

J. P. (2017). NIST special publication 800-63.

https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/sp800-63b.html.

Hassenzahl, M. and Monk, A. (2010). The inference of

perceived usability from beauty. Human–Computer

Interaction, 25(3):235–260.

Karlof, C., Tygar, J. D., and Wagner, D. (2009).

Conditioned-safe ceremonies and a user study of an

application to web authentication. In SOUPS. ACM

Press.

Karvonen, K. (2000). The beauty of simplicity. In CUU,

pages 85–90. ACM Press.

Kennedy, S. E. and Kennedy, S. E. (2016). The pathway to

security–mitigating user negligence. Information &

Computer Security, 24(3):255–264.

Martina, J. E., dos Santos, E., Carlos, M. C., Price, G., and

Cust

´

odio, R. F. (2015). An adaptive threat model for

security ceremonies. INT J INF SECUR, 14:103–121.

McMillan, R. (2017). The Man Who Wrote

Those Password Rules Has a New Tip.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-man-who-wrote-

those-password-rules-has-a-new-tip-n3v-r-m1-d-

1502124118.

Nass, C., Isbister, K., and Lee, E.-J. (2000). Truth is beauty:

Researching embodied conversational agents. In Em-

bodied Conversational Agents, pages 374–402.

Pancake, C. (2001). The ubiquitous beauty of user-aware

software. Commun. ACM, 44(3):130–130.

Peppa (2010). Peppa Pig, Series 3, Episode 38,

“The Secret Club”. https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=uDV2VdeNLnQ.

Portanova, M. S. (1975). Music is beauty. The Black Per-

spective in Music, 3(2):196–198.

Radke, K., Boyd, C., Nieto, J. M. G., and Brereton, M.

(2011). Ceremony analysis: Strengths and weak-

nesses. In 26th IFIP SEC, LNCS 354, pages 104–115.

Springer.

Reber, R., Schwarz, N., and Winkielman, P. (2004). Pro-

cessing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in

the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality

and social psychology review, 8(4):364–382.

Russell, B. (1956). The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell.

George Allen & Unwin.

Schechter, S., Brush, A. B., and Egelman, S. (2009). It’s

no secret. measuring the security and reliability of au-

thentication via secret questions. In 30th IEEE Sym-

posium on Security and Privacy, pages 375–390.

Sheng, S., Broderick, L., Koranda, C. A., and Hyland, J. J.

(2006). Why Johnny still can’t encrypt: evaluating

the usability of email encryption software. In SOUPS,

pages 3–4, ACM Press.

Stajano, F. (2011). Pico: No more passwords! In Secu-

rity Protocols Workshop, LNCS 7114, pages 49–81.

Springer.

Subashini, K. and Sumithra, G. (2014). Secure multimodal

mobile authentication using one time password. In

ICCTET, pages 151–155. IEEE CS Press.

Tatarkiewicz, W. (2006). History of Aesthetics: Edited by

J. Harrell, C. Barrett and D. Petsch. A&C Black.

Yildirim, E. (2016). The importance of information security

awareness for the success of business enterprises. In

Advances in Human Factors in Cybersecurity, pages

211–222. AISC, volume 501.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

136