Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity:

Findings of a Qualitative Research

Nelson Tenório

1 a

, Gisele Caroline Urbano Lourenço

2 b

, Mariana Oliveira

2 c

,

Steffi Aline Stark Becker

2 d

, Fabrício Tomaz Bernardelli

2 e

, Hassan Atifi

3 f

and Nada Matta

3 g

1

Cesumar Institute of Science, Technology and Innovation (ICETI), UniCesumar, Maringá, Paraná, Brazil

2

Masters’Program in Knowledge Management, UniCesumar, Maringá, Paraná, Brazil

3

Department of Computer Science, University of Technology of Troyes, Troyes, France

bernardelliwolf@gmail.com, {hassan.atifi, nada.matta}@utt.fr

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Knowledge Application, Solving Conflict, Individual Learning, Emotions.

Abstract: Hackathons are events that have become increasingly common around the world. This kind of event, described

as a programming marathon, is based on problem-solving that can go beyond the technological boundary.

This paper presents the findings of an international hackathon to aid its organizers to rethink their strategies

to improve the development of the team’s creativity to solve the challenge proposed. The paper summarizes

qualitative research based on interviews and observations which point out that the organizers should consider

strategies to improve knowledge application, resolving conflicts, individual learning, and experienced

emotions, during pre-hackathon as well as post-hackathon events. Our findings could leverage the innovation,

creativity, and knowledge sharing and creation within hackathons.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the means to stimulate innovation, creativity,

and to further knowledge creation and sharing is to

host a hackathon. Hackathons are events that became

common around the world. This kind of activity can

be described as a programming marathon which aims

to solve a challenge that can go beyond the

technological world (Vivanco-Galván, Castillo-

Malla, and Jiménez-Gaona, 2018). Flores et al.

(2018) point out that a hackathon is a competition

where participants work in teams for a short time, in

which they need to idealize, design, prototype, test

and launch their solutions to a given challenge. Those

events encourage both individual and organizational

learning through innovative ways (Briscoe and

Mulligan, 2014). Knowledge, then, is considered one

of the most valuable corporate assets. In this way, the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7339-013X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3407-5759

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9828-9233

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8464-0122

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1492-2554

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7895-3982

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8729-3624

organization that manages its knowledge benefits

from a hackathon and other activities has a higher

possibility to create innovative products and services,

remaining sustainable in the market in which it

operates (Nonaka, Toyama and Konno, 2000).

Knowledge Management (KM) is indispensable for

stimulating innovation in the organizations. KM is a

collection of processes that govern the creation and

dissemination of knowledge to achieve

organizational team goals (Dalkir, 2011).

Therefore, this paper aims to help hackathon

organizers to rethink strategies to increase the team’s

creativity during the event considering four

categories such as knowledge application, solving

conflicts, individual learning, and experienced

emotions, once those can directly impact in the

solutions proposed during the event.

Therefore, creativity is a trigger to increase

knowledge application (e.g., lecture, mentoring,

92

Tenório, N., Lourenço, G., Oliveira, M., Becker, S., Bernardelli, F., Atifi, H. and Matta, N.

Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity: Findings of a Qualitative Research.

DOI: 10.5220/0008164300920101

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 92-101

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

workshops) which might improve problem-solving.

Our lessons learned with resolving conflicts, for

instance, help the organizers to gather information

about team member’s conflicts during the hackathon

once it aids the groups to find ways for supporting in

the next event. Individual learning means that it is an

experience each participant has throughout the

hackathon and can be gained through interaction with

other activities, teams, or in specific situations.

Finally, emotions experienced, basically tiredness,

lead us to rethink the duration of hackathons, as well

as to promote such events during the daylight. Thus,

although the participants experienced different

positive situations at the event, tiredness was

highlighted as a challenge faced.

To show our findings, we organized this article

into six sections. Following this introduction, the

second section presents the concepts and related

works regarding KM, emotions, conflicts, and

individual learning. Next, the section presents our

research method followed by the empirical settings,

data collection, and data analysis. The chapter after

that summarizes the results and discussions followed

by our conclusions and the references.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Knowledge Management

Organizations have to manage their knowledge to get

business sustainability in a competitive market. In

this sense, Knowledge Management (KM) can be

useful as a resource for (managing) organizational

knowledge. According to Dalkir (2011), KM is the

deliberate and systemic coordination of people,

technologies, processes, and organizational structure

to add corporate value through knowledge reuse and

innovation. So, the organizations which manage their

knowledge to create innovative products and services,

remain sustainable in the market which they act

(Nonaka et al., 2008). In this sense, KM arises

through the process of knowledge creation, in which

it requires a physical environment to create new

knowledge. Regarding this, it’s necessary to highlight

two types of knowledge: implicit and explicit. For

Davenport and Prusak (2012), implicit knowledge is

complex, developed, and internalized by people over

a while, compounded by lifelong learning. Explicit

knowledge is easily communicated, either through

product specifications, scientific formulas, or

computer programs (Nonaka et al., 2000).

So, Nonaka and Takeuchi (1991) emphasize that

knowledge creation could start with socialization and

passes through the four modes of knowledge

conversions. The first of the methods is socialization,

which is presented as the sharing and creation of

implicit knowledge through direct experiences. The

authors identify the second method as outsourcing

that aims to articulate tacit knowledge through

dialogue. The third one is the combination; which

suggests both implicit and explicit knowledge

application. Finally, the fourth method is the

internalization, which suggests the needs to acquire

and learn new tacit knowledge in practice.

In this way, once the individual has the knowledge

internalized, it is necessary to apply this experience

so that the organization obtains sustainable

competitive advantage and profit.

Therefore, organizations which use the

knowledge appropriately may achieve competitive

advantages, reaching a notorious place in a

competitive market.

2.2 Emotions

The emotions are a legacy left by evolution that gives

the person impulses for immediate action. The

sentiment is the personal evaluation result of the

meaning of an event in the creation of its well-being

(Lazarus, 1991). Thus, emotions refer to feelings and

reasoning, psychological and biological states, and

the range of propensities for action. So, there are

hundreds of emotions, including their combinations,

variations, mutations, and shadows (Goleman, 2005).

Emotion is a complex reaction triggered by a

stimulus or thought with personal sensations, an

answer involving different components which it is a

notable reaction, a physiological excitation, a

cognitive interpretation, and subjective experience.

Moreover, it is a mental state of readiness that arises

from cognitive evaluations of events or thoughts, and

that can be perceived by gestures, postures and facial

features (Bagozzi, Gopinath, and Nyer, 1999).

Therefore, emotion is a natural way of evaluating the

environment that surrounds us and reacts adaptively

(Fredrickson, 1998).

Emotions are characterized as negative or

positive. One of the theories explaining negative and

positive emotions is so-called the ‘theory of control

over behavior’ considering that the view of behavior

can show the nature of emotions. The theory suggests

how feelings can arise and function in human

behavior (Carver and Scheier, 1990). Positive

emotions allow an individual to know what is being

done toward a desirable goal. In this context, there is

compelling evidence that positive emotions are not

just the result of well-being, but can also drive

Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity: Findings of a Qualitative Research

93

success and prosperity (Hazelton, 2014). Inversely,

negative emotions are the way of realizing that no

behavior, progress, or action is being taken toward

goals (Carver and Scheier, 1990). Negative emotions

occur when we perceive a negative meaning in

personal situation changes or related ones (Ben-Ze’ev

2000). These emotions represent a general dimension

of subjective suffering and unpleasant engagement

that includes a variety of aversive mood states,

including: anger, contempt, repulsion, guilt, fear, and

nervousness (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen, 1988);

frustrated, angry, depressed, harassed, hostile,

worried and unmotivated (Kahneman, 2004);

anxious, sad and angry (Fredrickson, 2001).

However, positive emotions work as effective

antidotes to the persistent effects of negative

emotions, correcting or undo the subsequent effects

of the negative emotions (Fredrickson, 2001). In this

sense, some positive emotions can be highlighted:

Joy, interest, contentment, love (Fredrickson, 2001);

Satisfaction, joy, pleasure, pride, relief, affection,

love, hope (Bagozzi, Gopinath and Nyer, 1999).

2.3 Conflicts

Conflicts may occur in a wide range of settings

involving people in a work process. Those conflicts

are social and psychological phenomena in which

they have different sources, processes, and results.

So, various disciplines, such as sociology, economics,

philosophy, and management, try to explain the

conflicts in different ways (Wu, 2017).

Thomas (1974) points out that conflict is a process

that begins when one party realizes that the other had

frustrated or was about to disappoint some of their

concerns. In this way, conflict can be described as a

state, in which disharmonious phenomena trigger

hostile actions, under a state of confrontation or

emotion. However, conflicts are widespread in

today’s world due to the competition and the growing

expectations of all business stakeholders (Wang, Fink

and Cai, 2012), the conflict is used as an indicator of

a lack of reliability of some sources. Thus, adopting

appropriate conduct it’s for such situations (Pichon,

Jousselme, and Ben Abdallah, 2019).

According to Rao (2017), conflicts can occur for

a variety of reasons, e.g., personality clashes, ego

clashes, differences of opinion or culture,

perceptions, lack of communication, lack of

information, ambiguity in roles and responsibilities,

stress and lack of resources. Regarding this scenario,

conflicts arise when there is a gap between

expectations and realities, being possible, then two

types of conflicts: interpersonal - those that occur

within the individuals, and the conflict between

several groups - known as ‘group conflicts.’

However, if the conflicts are not well resolved,

they can have detrimental effects on the progress of

an organization, team, or project (Chen, Zhang, and

Zhang, 2014). It could also reduce the creative

process (Reiter-Palmon and Murugavel, 2018) once

this confrontational relationship makes it difficult to

reach a project, team or organization goal, resulting

in excessive expenses of time and costs (Hwang,

Zhao, and Ng, 2013). Therefore, more attention

should be given to finding out the critical factors of

projects conflicts and related mechanisms. Thus,

dealing with conflict means effectively resolving, a

possible disagreement could happen between one

another and others, in which it occurs because no two

equal persons perform and think the same task in the

same way (Rao, 2017).

Thus, conflicts can exist in an organization, team,

or project, and the expertise to deal with such disputes

is essential. The lack of conflict’s experience causes

the loss of time and resources of poorly resolved

conflicts; those could be strategically applied in an

organization, team, or project.

2.4 Individual Learning

The concept of individual learning as an object of

study is still uncommon in the literature since it is

relatively new and, as of that moment, not much is

known about its conceptualization and empirical

basis (Poell and der Krogt, 2010).

However, individual learning can be described as

a lifelong process in which it is possible to learn and

develop cognitive skills (Cornford, 2007). Also,

Sanchez (2003) emphasizes that the learning is the

personal experience throughout the life which occurs

individually, through the person’s interaction with

groups of people, or in situations lived in its work

environment (Sanchez, 2003). In this sense, all the

interactions of the individuals are incorporated into

the person’s lifelong learning. This learning later

becomes knowledge that will be shared with other

individuals (Melo and Araújo, 2007).

A unique learning project is one that has a specific

time, and that seeks to teach some relevant subjects to

the individual (Roberson and Merriam, 2005). One of

the reasons for using an individual learning project

refers to the fact that individuals need other ones to

learn. This context can come from friends, co-

workers, or anyone who contributes to the personal

learning process by providing models and

constructive feedback (Hara et al., 1996). Thus, a

unique learning project is in a constructivist

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

94

approach, in that it can be adherent to diverse

contexts, e.g., personal or work, for the individual

(Voinea and Purcaru, 2015). Therefore, collaboration

for individual learning can be a way out once the help

of one’s specific knowledge can be learned in practice

(Zambrano et al., 2019).

Therefore, interactions with other people may

help in to acquire individual learning. So, this

learning can become a solid knowledge use when

required.

3 HACKATHONS AND KM

Hackathons are events in which they use different

cultures and expertise regarding that each participant

applies their vision to solve a specific challenge

(Seravalli and Simeone, 2016). To solve a hackathon

challenge, the participants have an opportunity to

communicate with each other, providing insights into

the creation of the content (Serrano-Laguna et al.,

2015). Thus, hackathons provide means to share and

create knowledge by seeking solutions to everyday

problems posed as challenges by resorting to the

production of innovative software for the benefit of

society.

According to Zukin and Papadantonakis (2017),

hackathons promote the opportunity for participants

to learn new skills, e.g., computer code creation,

application creation, and mockups, as well as

providing face-to-face networking. In this way,

hackathons stimulate the creativity of participants,

who have the opportunity to deal with technology

(Richterich, 2017). However, hackathons are

applicable in a variety of settings, as they seek

innovative solutions for a real challenge (Calco and

Veeck, 2015).

In this context, Briscoe and Mulligan (2014)

emphasize that hackathons have been stimulated in

different areas such as music, fashion, and fitness.

Thus, the authors further underline that the

hackathons are encouraging of experimentations and

creativity, being able, then, to aim different

challenges. Hackathons, therefore, aim to stimulate

innovation as individuals share ideas and seek

solutions to the problems presented (Lourenço et al.,

2018).

From the perspective of the KM, hackathon

becomes a tool for creating and sharing knowledge in

a group. It makes sense once this type of event

encourages its participants to work in teams, sharing

information for generating experience on the

challenges. The dynamism of creation can be seen

through Nonaka's theory (1994), which suggests that

knowledge can be created through socialization (tacit

to tacit), externalization (tacit to explicit),

internalization (explicit to implicit), and combination

(explicit to explicit). It is in the explication and union

of these two elements that the creation of knowledge

intervenes. So, some organizations formally

encourage and support practices once they consider

the event benefits the creation and sharing of

knowledge regarding innovation. They do that

sponsoring and supporting internal or external

hackathons around the world.

However, hackathons provide participants an

environment that helps to learn new skills as well as

interaction with other participants and networking.

Thus, hackathons stimulate the participants' creativity

to solve a real challenge.

4 METHOD

To present the findings of an international hackathon

to aid its organizers to rethink their improvement

strategies of team’s development creativity to solve

the challenges of the hackathon; we used the

qualitative methodology suggested by Creswell and

Creswell (2017), and empirical evidence based on a

case study. The same approach was used through

interviews and observations during the event. The

hackathon took place between 19 and 21 of October

of 2018. The inspections were performed during the

first two days of the event, aiming to identify how

team members create and share knowledge among the

other members. On the third and last day, we

performed face to face interviews, conducted with the

participants, through a semi-structured interview

protocol. This strategy was adopted so that the

interviewees could consider all the elements involved

in the course of the event. The findings showed in this

article are based on this empirical material, which was

recorded, transcribed, analyzed, and, finally,

discussed based on theoretical reference.

4.1 Empirical Settings

Hackathons are public marathons that involve

participants for hours, days or weeks to discuss ideas

and develop software or hardware projects that can

create or disseminate productions and especially

digital innovations (Topi, 2014, Leckart, 2012).

Usually, such events are sponsored by entities (public

or private), which presents a challenge to the

participants, being related to the most diverse areas of

knowledge. They are divided into teams that must

propose solutions for the proposed trial. Hackathon

Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity: Findings of a Qualitative Research

95

event is the scenario behind NASA Space Apps, a

NASA-sponsored hackathon. The event was held

between October 19, 2018, until October 21 of the

same year and involved professionals and students

from different fields of knowledge. The Space Apps

event took place simultaneously in 75 countries, with

more than eighteen thousand participants (Space

Apps Challenge, 2018). The event was taking place

by a University in the city of Maringá, Brazil. During

the three days of the event, several activities took

place. On Saturday morning (the first day of the

challenge) mini-courses, workshops and mentoring

were held. The participants randomly segregated into

teams, had twenty-four hours to develop projects on

one of six themes set by NASA: freestyle, better

earth, natural impact, big rocks, the kryos, and space

mindfulness. At the end of these twenty-four hours,

the teams were previously submitted to an examining

board, composed by the mentors of the event, who

evaluated the solutions presented in each project and

selected the ten best ones, which were presented to

the other teams and the appraisers invited to the event

in the afternoon. After the introductions, the

appraisers chose the best works. In this way, the

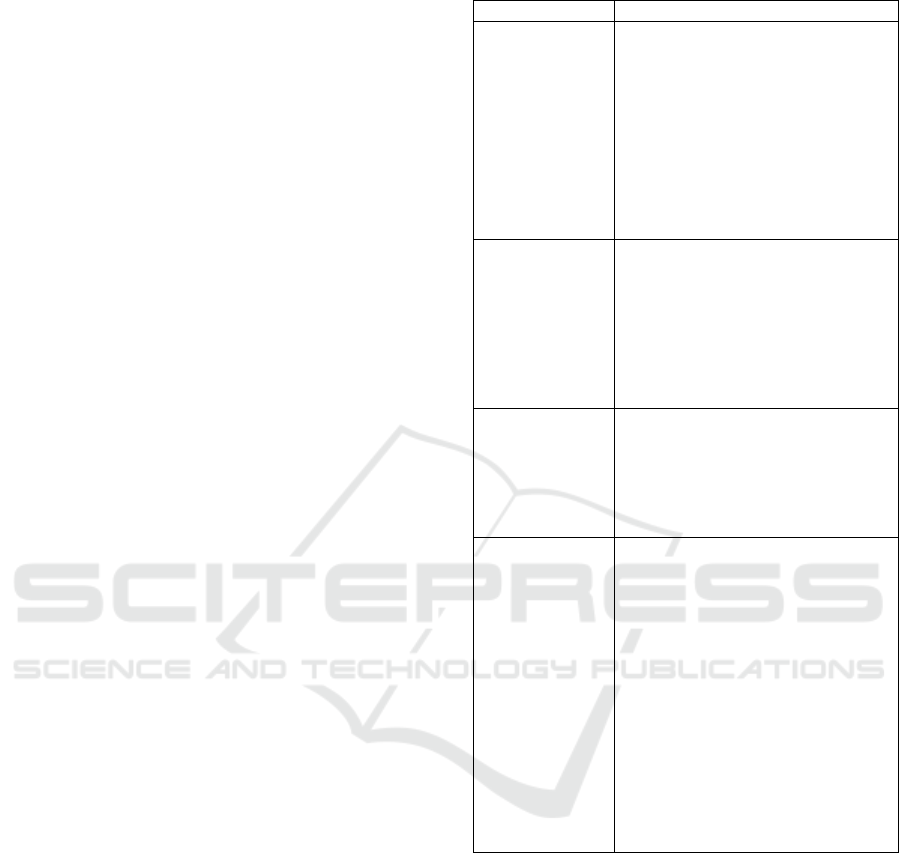

research was carried out in five phases, as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research steps.

The first step consisted in searching for publications

related to the subject of this research, carried out in

the databases: Science Direct, Emerald Insight, ACM

Digital Library, and Capes Research Website. The

following keywords were used in Portuguese and

English: knowledge management, individual

knowledge, conflicts, and hackathons. These

keywords were chosen because they seek to support

the theme proposed here. The second step, the

development of a semi-structured interview protocol

consisted of ten questions, which aims to understand

how the interaction between the participants

happened. In the third step, the interviews were

conducted face to face with the participants during the

days of the event. The duration of each interview had

an 8 minutes average. In the third step, the interviews

were analyzed based on content analysis. Finally, the

presentation and discussion of the research results

were discussed looking at the literature and relating it

to the findings.

4.2 Data Collection

Data was gathered through the interview’s

observation conducted with the hackathon's

participants through an interview protocol, as

suggested by Creswell and Creswell (2017). The

inspection and the interviews occurred only with the

participants in the city of Maringá, Brazil. All the

material was recorded with the interviewee’s

permission. During the first two days of the

hackathon, the observations were focused on

interaction among the team members. We did our

views for twenty-five hours from 21st to 22nd of

October 2018. On the last day (22nd of October), after

the pits, we conducted interviews with participants

from eight different teams. Such a method was used

in the data collection so that the interviewees could

report their experiences during the whole event. The

interviewees were selected by intentional sampling.

This type of sampling provides in-depth data on what

is being researched (Creswell, Creswell, 2017). The

interview protocol contained ten open questions

where the participants reported their experiences

before the event and skills gained during the current

hackathon, as well as their perceptions regarding the

interaction between all the participants (team level or

not). The interviews were carried out in a room at the

same place as the hackathon.

4.3 Data Analysis

Data analysis is the essence of qualitative research,

which consists the data interpretation and, identifying

means that was refined by researchers (Creswell and

Creswell 2017). Among the many methods used to

analyze interviews, we used the content analysis

(CA), suggested by Bardin (1977). This method aims

to obtain, through a set of indicator techniques that

allow the "inference of knowledge regarding the

conditions of production/reception" of the analyzed

content, i.e., analyses what was said by the

participants in the interviews (Bardin, 1977).

For the interviews to perform the data collection,

the ones were transcribed word by word. Afterward,

interview transcripts were analyzed to understand

Step 1: Bibliographic research

Step 2: Development of the

instrument of data collection

Step 3: Conducting the interviews

Step 4: Data analysis

Step 5: Presentation of Results

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

96

how the knowledge was internalized among the

participants, highlighting important perceptions and

experiences regarding their participation.

5 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The interviews came out with interesting findings,

showed in four categories as follows: knowledge

application, solving conflicts, individual learning,

and experienced emotions. Those categories mean

that:

Knowledge Application: Participants bring their

experience to combine with a newly acquired

knowledge providing a sustainable and competitive

advantage for the problem solve in the hackathon. In

this context, the ‘Interviewee IV’ quoted his/her

previous experience, which aids him/her.

“Even being my first year at the university, I have

already applied some of my knowledge which I have

brought from my personal experiences [to the

hackathon].” (Interviewee IV, 21/10/2018).

In this way, we observed that the interviewee was

able to apply the knowledge acquired during his/her

first University year in an appropriated solution into

the hackathon. Considering this, the ‘Interviewee

VII’ reported to us that s[he] worked in the software

development area and applied his/her knowledge to

design their solution of the hackathon’s challenge.

“I already work in the area, and I was able to apply

my knowledge of design and to prototype a good

solution for my team. I hope to help with them

promptly.” (Interviewee VII, 21/10/2018).

Looking at those quotes carefully, we observe

that knowledge application occurs when the actual

use of knowledge has been captured or created and

put into the KM cycle (Dalkir, 2011). Hackathons

follow a KM cycle, i.e., Nonaka (1994) SECI model.

Once the team members perform socialization which

provides knowledge creation through their interaction

(tacit to tacit); externalization since they’re designing

and discussing the solution of the challenge (implicit

to explicit); internalization whereas team members

understand the answer (explicit to implicit); and,

finally, combination in which team members can use

previous experience with new acquire knowledge to

propose solutions to hackathon’s challenge (explicit

to explicit). So, in hackathons, the individual’s tacit

knowledge is the leading way to solve the problems

once the essence of problem-solving, innovative

suggestions, creativity, design, analysis, and project

management is based on more implicit, rather than

explicit knowledge. In this sense, the hackathon

organizers must rethink the ways to potentialize

knowledge application to stimulate creativity and,

consequently, knowledge creation, problem-solving,

and innovation. They must offer pre-events such as

workshops, coaching, training, mentoring, and so on.

The NASA hackathon suggests a pre-event, namely

boot camp. The boot camp intends to ‘equalize’ team

members knowledge to figure out the challenge with

innovative solutions. We have observed different

kinds of hackathons in our region; however, the

hackathons which do not provide pre-events end up

less innovative products than those which does.

Therefore, we observed that pre-events have shown

essential to promote knowledge application.

Solving Conflicts: Through the interviews emerged

concerns regarding frequent disagreements within the

team during the hackathon. Those conflicts comprise

different proposals to solve the challenges presented

by the hackathon organizers. When the conflict

raised, the participants act differently to resolve such

dispute. The ‘Interviewee VIII’ reported to us his/her

strategy to solve conflicts during the hackathon.

“There were many different opinions to define the

project, so we decided to take place a ‘vote system’

to support our decision.” (Interviewee VIII,

21/10/2018).

Thus, voting was conduct used as a criterion for a

fair decision among the participants. This voting took

place in an open manner in which the project to be

voted on was presented to all, and from that, the

participants expressed their opinion by one vote. We

also observed some people stressful or discouraged at

the beginning of the hackathon once the team did not

accept their ideas and even criticized those hardly.

Those kinds of conflicts, referred to the divergence of

opinion, use to occur during the solution design, i.e.,

when the team is discussing the challenge and the

ways to figure it out. While the ‘Interviewee VIII’

reported us a voting system as a strategy to choose an

idea and mitigate the conflict, the ‘Interviewee IV’

was discouraged from presenting his/her ideas since

no one agreed with it and further wanted that their

ideas were accepted, as show the quote below.

“I had several ideas, but each one wanted different

things with different ideas, [...] that conflict

discouraged me.” (Interviewee IV, 21/10/2018).

More important than ideas are the way to solve the

conflicts and, further not discourage the team

members. However, even with the conflicts that

permeated the 'Interviewed IV' team reported that a

solution could be found through final consensus.

Thereby, ‘Interviewee II’ reported us the absence of

conflict inside his/her team, as shown quote below.

“There was no disagreement in our team, each one

of us arrived with three proposals, and we were

tapering them considering positive and negative

Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity: Findings of a Qualitative Research

97

points. We discussed each one of those proposals, and

we ranked those that would be most interesting until

we reached an agreement of the team members. So, I

cannot say that there was a conflict.” (Interviewee II,

21/10/2018).

Like this, ‘Interviewee II’ describes no conflicts

into his team and an excellent strategy to figure the

conflicts out once the groups suffered from team

disagreements, mainly during the creative process.

This kind of disputes results in lowered creativity

(Reiter-Palmon and Murugavel, 2018).

Understanding more about the conflicts is relevant to

hackathon’s organizers once it could improve the

quality of the solutions. So, the organizers should

collect information regarding conflicts occurred

within team members during the challenge. It

concerns to learn more about discussions and

organize means to support teams to figure their

conflict out in the next event. One possibility to avoid

team conflict is offering lectures to the participants

regarding interpersonal relationship within the pre-

event. Those lectures could be conducted by inviting

psychology students to give those lectures presenting

techniques to solve the conflicts.

Individual Learning: This category refers to a lifelong

process that an individual learns and develop his

cognitive skills. We know that each hackathon

provides means to individuals to learn about the

challenge, solution, interpersonal relationship,

technology, and so on. The ‘Interviewee III’ reported

what his/her learning in the hackathon, as quoted

below.

“In this hackathon, I learned how to work within a

team and also learned from my team different point

of views of the problem we were working on”

(Interviewee III, 21/10/2018).

Thus, we observed clearly that the participant

learned some new within the hackathon. Another

participant reported to us about his/her skill to interact

with other people has been evolved.

“I felt that my skill to interact with other people

evolved in this hackathon” (Interviewee IV,

21/10/2018).

Thus, we observed that the participant has been

able to improve his interactions with the hackathon,

reinforcing the idea that the learning can occur with

the interactions. And such communications promote

socialization among participants, which can facilitate

the creation of ideas and insights about the project

undertaken. Finally, the quote below shows the

‘Interviewee V’ talking about

“I have learned useful things in this hackathon to

be practiced out of here and in my life, such as

interpersonal relationship, technology skills, and the

spirit of competition” (Interviewee V, 21/10/2018).

Thus, it is possible to observe that all respondents

reported that a hackathon is an event in which it

facilitates learning practically and interactively. This

solid form refers to the fact that such projects are

elaborated and executed during the same period of the

event. And the interactive way can be related to the

socialization that the event provides among the

participants. Once hackathons are events of

challenges based on basic functionalities due to the

short time of the event, Roberson and Merriam (2005)

highlight that the individual learning project is one

that has a specific time, seeking to teach something

relevant from the project and interaction with the

team. Working on a project, the individuals might

learn in practice, internalizing their knowledge

(Dalkir, 2011, Takeuchi, 1994). Thus, hackathons

bring a constructivist approach in which aligned to

different personal or work contexts (Voinea and

Purcaru, 2015). Thus, the hackathon organizers

should stimulate individual learning in hackathons

offering online courses, mentoring, and materials

before the hackathon beginning to afford ideas and

creativity to the participants.

I experienced emotions. The ‘Interviewee VIII’

revealed some perceptions regarding his/her feelings

during the hackathon.

“I’m feeling pleased here [in the hackathon];

however, I’m feeling tired because I’m in the event

since it started [twelve-hours]” (Interviewee VIII,

21/10/2018).

Thus, we observed that even though of the

participant happiness during the event, the participant

reported tiredness due to its long-time duration. The

‘Interviewee I’ highlighted his/her fatigue even

having fun in the hackathon and having an

environment in which provided such joy and

engagement.

“The hackathon was a lot of fun and a motivating

environment, but after a while, it gets very tiring”

(Interviewee I, 21/10/2018).

In the same sense, another interviewee

commented:

“There were disagreements over tiredness, but

everything was decided in the vote” (Interviewee VII,

21/10/2018).

The participants experienced different emotions,

some of them positive (i.e., happiness and fun) in

contrast with tiredness. According to Fredrickson

(1998), the effects of positive emotions share the

capacity to enlarge people's momentary repertoires

and create their enduring personal resources, from

physical and intellectual resources to social and

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

98

psychological resources. Positive emotions occur

when positive related changes are perceived,

significantly improving a situation (Ben-Ze’ev,

2000). The positive ones reflect how much a person

feels enthusiastic, active, and alert, being a state of

high energy, total concentration, and pleasurable

engagement (Watson, Clark, and Tellegen, 1988).

Also, the other participant highlighted the happiness

of attending the event.

However, looking inside the hackathons, if on the

one hand, we observed the motivation and

engagement by the participants; on the other hand, we

found tiredness and discouragement. Despite an

environment all prepared and conducive to creativity,

we noted some team members are giving up their

participating in the hackathon. Unfortunately, we

have not interviewed the members who gave up of the

event, but we interviewed some of their team

members in which reported us some motivations of

the withdrawal of its members namely tiredness,

discouraged, and afraid to be ashamed of the

proposed solution during the pits.

Based on this kind of behavior, we should rethink

hackathon’s design trying to avoid those negative

emotions (i.e., tiredness, discouraged, and afraid).

Firstly, hackathons’ organizers should reduce twenty-

four hours to twelve-hours proposing short challenges

in a format of mini-hackathons like mini-marathons.

Secondly, take place the hackathons during daylight,

e.g., three days of eight-hours-day. Finally, allow

some members, particularly those whose feel more

tiring, might participate virtually.

Therefore, our findings pointed out that

hackathon’s organizers should rethink the design of

the hackathons considering four categories. The first

category, knowledge application, shows that

hackathon takes place a KM cycle which converts

knowledge tacit to explicit and vice-versa, providing

knowledge sharing and creation. The second

category, solving conflicts, show a fragility of the

team members to handle with the clash of ideas and

how this is detrimental to the team's creativity and

coexistence during the event most of the times

discourage the team members from continuing the

challenges. The third category brought to us how

individual learning is essential to and should be

stimulated before the event to improve the solutions

to afford ideas and creativity to the participants.

Finally, the fourth category, namely experienced

emotions, show how relevant is the feelings of the

individuals during the event and how the tiredness

can be unfavorable to solve the challenges given in

the hackathon. Table 1 summarizes our findings.

Table 1: Findings summarized.

Finding

Strategy

Knowledge

application

Potentialize:

problem-solving,

innovation,

the creativity of the

participants

Offering pre-events such

workshops

coaching

training

mentoring

Solving

conflicts

Collection

information regarding

conflicts occurred within

team members

Try to avoid conflicts offering

pre-hackathon

interpersonal relationship

training

Individual

learning

Stimulate individual learning in

hackathons

online courses

mentoring

materials before the

hackathon beginning

Experienced

emotions

Avoid negative emotions

tiredness

discouraged

afraid

Reduce twenty-four hours to twelve-

hours short challenges (mini-

hackathon)

Take place the hackathons during

daylight (e.g., three days of eight-

hours-day)

Allow members who feel tiring, to

participate virtually

6 CONCLUSION

This article aims to present the findings of an

international hackathon to help its organizers rethink

their strategies for improving creativity and

innovative ideas to solve the proposed challenge. To

this end, qualitative research was conducted, which

used observation and interviews with the participants

of the event. The results pointed out that organizers

should consider strategies for improving knowledge

application, conflict resolution, individual learning,

and emotions experienced during pre-hackathon and

post-hackathon. This is because, through these

Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity: Findings of a Qualitative Research

99

strategies, new opportunities are possible in such

events. In this way, these discoveries could leverage

innovation, creativity, and knowledge created within

hackathons. Thus, the main contribution of this article

is the presentation of strategies to make this world-

class hackathon more productive for participants and

organizers. As future work, we intend to test our

findings in a real marathon and analyze the results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our special thanks to Instituto Cesumar de Ciência,

Tecnologia e Inovação (ICETI) Maringá, Paraná

Brasil. We also thanks to Programa de Suporte a Pós-

Graduação de Instituições de Ensino Particulares

(PROSUP) da CAPES (Coordenação de

Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior).

REFERENCES

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M. Nyer, P. U., 1999. The Role

of Emotions in Marketing. Journal of the academy of

marketing science, 27(2), 184–206.

Bardin, L., 1977. Análise de Conteúdo. Edições 70: Lisboa.

Ben-Ze’ev, A., 2000. The Subtlety of Emotions. A Bradford

Book. MIT Press: Cambridge.

Briscoe, G., Mulligan, C., 2014. Digital Innovation: The

Hackathon Phenomenon, Creativeworks London, (6),

1–13.

Calco, M., Veeck, A., 2015. The Markathon: Adapting the

Hackathon Model for an Introductory Marketing Class

Project, Marketing Education Review, 25(1), 33–38.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., 1990. Origins and functions

of positive and negative affect: A control-process view.

Psychological review. 97(1), 19–35.

CEN., 2004. European Guide to good Practice in

Knowledge Management - Part 1 to 5, Brussels.

Cummings, J.N. Work Groups, Structural Diversity,

and Knowledge Sharing in a Global Organization,

Management Science, 50(3), 352-364.

Chen, Y. Q., Zhang, Y. B., Zhang, S. J., 2014. Impacts of

Different Types of Owner-Contractor Conflict on Cost

Performance in Construction Projects. Journal of

Construction Engineering and Management, 140(6),

040140171- 040140178.

Creswell, J. W., Creswell, J. D., 2017 Research design:

Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods

approaches. Sage publications: Thousand Oaks.

Dalkir, K., 2011. Knowledge management in theory and

practice. MIT press: Cambridge.

Davenport, T. H., Prusak, L., 2012. Conhecimento

Empresarial: Como as Organizações Gerenciam seu

Capital Intelectual. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

Cornford, I. R., 2007. Imperatives in Teaching for Lifelong

Learning: moving beyond rhetoric to effective

educational practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher

Education. 27(2), 107-117.

Flores, M., Golob, M., Maklin, D., Herrera, M., Tucci, C.,

Al-Ashaab, A., Williams, L., Encinas, A., Martinez, V.,

Zaki, M., Sosa, L., Flores Pineda, K., 2018. How Can

Hackathons Accelerate Corporate Innovation?

Cambridge Service Alliance, 1, 1–8.

Fredrickson, B. L., 1998. What Good Are Positive

Emotions? Review of general psychology, 2(3), 300–

319.

Fredrickson, B. L., 2001. The Role of Positive Emotions in

Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory

of Positive Emotions. American psychologist, 56(3),

218–226.

Goleman, D., 2005. Emotional Intelligence - 10th

Anniversary. Bantam Books: New York.

Hara, S. O., Lecturer, S., Development, M., Sayers, E.,

Consultant, S., Windsor, O., 1996. Organizational

change through individual learning. Career

Development International, 1(4), 38–41.

Hazelton, S., 2014. Positive emotions boost employee

engagement. Human Resource Management

International Digest, 22(1), 34–37.

Hwang, B.-G., Zhao, X., Ng, S. Y., 2013. Identifying the

critical factors affecting schedule performance of

public housing projects, Habitat International, 38, 214–

221.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz,

N., Stone, A. A., 2004. A survey method for

characterizing daily life experience: The day

reconstruction method. Science, 306(5702), 1776–

1780.

Lazarus, R. S., 1991. Cognition and motivation in emotion.

American psychologist, 46(4), 352–367.

Leckart, S., 2012. The hackathon is on: Pitching and

programming the next killer app. Wired: San Francisco.

Lourenço, G. C. U., Gonçalves, R. D. C. B., Oliveira, G. M.

DE, Tenório, N., 2018. Aprendizagem Na Indústria De

Software: A Investigação De Um Hackathon Interno.

In: ENEPE - Encontro de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão

da Unoeste.

Liyanage, C., Elhag, T., Ballal, T., Li, Q., 2009. Knowledge

communication and translation - a knowledge transfer

model. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(3),

118–131.

Melo, A. V. C. de, Araújo, E. A. de., 2007. Competência

informacional e gestão do conhecimento: uma relação

necessária no contexto da sociedade da informação.

Perspectivas em Ciência da Informação, 12 (2).

Nonaka, I., 1994. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation, Organization Science, 5(1), 14-

37.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. Konno, N., 2000. SECI, Ba and

Leadership: a unified model of dynamic knowledge

creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 5–34.

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H., 1991. The knowledge-creating

company. Harvard Business Review, 85(7/8), 162.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., Hirata, T., Bigelow, S. J., Hirose,

A., & Kohlbacher, F., 2008. Managing

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

100

Flow. Managing Flow: A Process Theory of the

Knowledge-Based Firm. Palgrave Macmillan: London.

Nyer, P. U., 1997. A Study of the Relationships Between

Cognitive Appraisals and Consumption Emotions.

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(4),

296-304.

Pichon, F., Jousselme, A., & Ben Abdallah, N., 2019.

Several shades of conflict. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 366,

63–84.

Poell, R. F., der Krogt, F. J., 2010. Individual learning paths

of employees in the context of social networks. In

Learning through Practice: Models, Traditions,

Orientations and Approaches. Springer: Netherlands.

Rao, M. S., 2017. Tools and techniques to resolve

organizational conflicts amicably, Industrial and

Commercial Training, 49(2), 93–97.

Reiter-Palmon, R., Murugavel, V., 2018. The Effect of

Problem Construction on Team Process and Creativity.

Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2098.

Richterich, A., 2017. Hacking events, Convergence: The

International Journal of Research into New Media

Technologies, 1-26.

Roberson, D. N., Merriam, S. B., 2005. The self-directed

learning process of older, rural adults Adult Education

Quarterly, 55(4), 269-287.

Sanchez, R., 2003. Knowledge management and

organization competence. Oxford University Press:

New York.

Seravalli, A., Simeone, L., 2016. Performing hackathons as

a way of positioning boundary organizations, Journal

of Organizational Change Management, 29(3), 326–

343.

Serrano-Laguna, Á., Rotaru, D.-C., Calvo-Morata, A.,

Torrente, J., Fernández-Manjón, B., 2015. Creating

Interactive Content in Android Devices: The Mokap

Hackathon, In: International Symposium on End User

Development, 287–290.

Song, M., Van Der Bij, H., Weggeman, M., 2005.

Determinants of the level of knowledge application: A

knowledge-based and information-processing

perspective. Journal of Product Innovation

Management, 22(5), 430–444.

Space Apps Challenge., 2018. Available in:

https://2018.spaceappschallenge.org/ Accessed in:

01/04/2018.

Thomas, K. W., 1974. Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode

Instrument. Xicom: New York.

Topi, H., Tucker, A., 2014. Computing handbook:

Information systems and information technology.

Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York.

Vivanco-Galván, O. A., Castillo-Malla, D., Jiménez-

Gaona, Y., 2018. Hackathon multidisciplinario:

fortalecimiento del aprendizaje basado en proyectos,

Revista Electrónica calidad en la educacion superior,

9(1), 119–135.

Voinea, M., Purcaru, M., 2015. Individual Learning Plan in

Teaching Mathematics for Children with SEN–A

Constructivist Approach. Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 187, 190–195.

Wang, Q., Fink, E. L., Cai, D. A., 2012. The Effect of

Conflict Goals on Avoidance Strategies: What Does

Not Communicating Communicate?, Human

Communication Research, 38(2), 222-252.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. Tellegen, A., 1988. Development

and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and

Negative Affect: The PANAS Scale. Journal of

personality and social psychology, 54(6), 1063.

Wiig, K. M., 1993. Knowledge Management Foundations:

Thinking about Thinking - how People and

Organizations Represent, Create, and Use

Knowledge. Schema Press: Arlington.

Wu, G., Zhao, X., Zuo, J., 2017. Effects of inter-

organizational conflicts on construction project added

value in China, International Journal of Conflict

Management, 28(5), 695–723.

Zambrano R., J., Kirschner, F., Sweller, J., Kirschner, P.

A., 2019 . Effects of prior knowledge on collaborative

and individual learning. Learning and Instruction.

Learning and Instruction 63(August 2018), 101214.

Zukin, S., Papadantonakis, M., 2017. Hackathons as Co-

optation Ritual: Socializing Workers and

Institutionalizing Innovation in the “New” Economy’,

In: Precarious Work. Emerald Publishing Limited:

Bingley, 157–181.

Rethinking Strategies of Hackathons to Increase Team’s Creativity: Findings of a Qualitative Research

101