Fruitful Synergies between Computer Science, Historical Studies and

Archives: The Experience in the PRiSMHA Project

Annamaria Goy

1

, Cristina Accornero

2

, Dunia Astrologo

3

, Davide Colla

1

, Matteo D’Ambrosio

3

,

Rossana Damiano

1

, Marco Leontino

1

, Antonio Lieto

1

, Fabrizio Loreto

2

, Diego Magro

1

,

Enrico Mensa

1

, Alice Montanaro

1,3

, Valeria Mosca

3

, Stefano Musso

2

, Daniele P. Radicioni

1

and Cristina Re

1,3

1

Dipartimento di Informatica, Università di Torino, Torino, Italy

2

Dipartimento di Studi Storici, Università di Torino, Torino, Italy

3

Fondazione Istituto Piemontese Antonio Gramsci, Torino, Italy

{annamaria.goy, davide.colla, rossana.damiano, antonio.lieto, fabrizio.loreto, diego.magro, enrico.mensa, stefano.musso,

cristina.re90}@gmail.com, valeria.mosca1@virgilio.it

Keywords: Intelligent Information Systems, Semantic Web, Multidisciplinary Approach, Digital Humanities, Historical

Archives.

Abstract: In this paper we present the mid-term results of the PRiSMHA project, aimed to contribute in building a

digital “smart archivist”, i.e., a web-based system providing an innovative access to historical archives. Such

a system is endowed with a semantic layer over existing archival metadata, including computational

ontologies and a knowledge base, containing a formal description of the content of the documents stored in

the archives. The paper focuses on the fruitful synergies employed to reach its goal. In particular, it explains

the steps of the “spiral” process implemented for creating a full-fledged formal semantic model, through the

interaction between computer scientists, historians, and archivists. The paper also presents some “core side-

effects” of this process: an analytical card for each document has been produced, all selected documents have

been digitized, OCR-ized (when possible), and linked to a record on the archival platform. This experience

enabled us to define a virtuous procedural model, from the paper documents up to the digital “smart archivist”,

based on a close collaboration between universities and cultural and historical institutions.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper we present the mid-term results of

PRiSMHA (Providing Rich Semantic Metadata for

Historical Archives), a three-year national project

(2017-2020), funded by Compagnia di San Paolo and

Università di Torino (Goy et al., 2017). PRiSMHA

(di.unito.it/prismha) involves the Computer Science

and the Historical Studies Departments of the

University of Torino (Italy), and relies on a close

collaboration with the Polo del '900

(www.polodel900.it), a cultural center in Torino, co-

funded by Compagnia di San Paolo, Comune di

Torino and Regione Piemonte. It involves nineteen

institutions and hosts a very rich set of archives, a

quarter of which is provided by the Fondazione

Istituto Piemontese Antonio Gramsci

(www.gramscitorino.it). The Polo del '900 archives

can be accessed through the online platform 9centRo

(www.polodel900.it/9centro).

In the following, we start by presenting the overall

framework in which PRiSMHA takes part (Section

2). Then we describe PRiSMHA's specific role and its

main results at the mid-term milestone, by focusing

on the fruitful synergies between different

perspectives: historical studies and computer science,

research institutions and cultural centers, automatic

and user-driven data production (Section 3). We

conclude the paper by indicating some future research

directions (Section 4).

2 THE FRAMEWORK

The overall goal is to build a digital “smart archivist”,

i.e., a web-based system providing an intelligent

access to historical archives.

Goy, A., Accornero, C., Astrologo, D., Colla, D., D’Ambrosio, M., Damiano, R., Leontino, M., Lieto, A., Loreto, F., Magro, D., Mensa, E., Montanaro, A., Mosca, V., Musso, S., Radicioni, D. and

Re, C.

Fruitful Synergies between Computer Science, Historical Studies and Archives: The Experience in the PRiSMHA Project.

DOI: 10.5220/0008343802250230

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 225-230

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

225

Let us consider the case of a young researcher

looking for primary sources (leaflets, pictures, letters,

etc.) that report or comment on violent actions

performed by the police against students and workers

during the social protest in 1968. A digital “smart

archivist” would provide all documents somehow

referring to such kind of actions, independently from

the words actually used to report them in the primary

sources.

In order to reach such a result, a simple keyword

or tag-based search is not enough. As the long

tradition of studies in Knowledge Representation and

Reasoning in the field of Artificial Intelligence

tells us, in order to be “intelligent”, the system must

“know” the documents and grasp their content.

Therefore, the goal is providing the system with

further machine readable knowledge than that

actually represented by words occurring in the

documents or in their textual metadata. Technically,

this means building a semantic layer over existing

archival metadata, including:

Computational ontologies (Guarino et al., 2009)

representing the semantic “vocabulary” (Goy et

al., 2015);

A knowledge base containing a detailed formal

description of: the events narrated in the

documents, the places where they happened,

people, organizations, and collectives involved in

them, together with the role they played.

In order to guarantee the needed computational

interoperability, the standards of the Semantic Web

must be employed: OWL 2 (Hitzler et al., 2012) for

the computational ontologies and RDF (Hayes and

Patel-Schneider, 2014) and the Linked Data

principles (Heath and Bizer, 2011) for the knowledge

base.

However, providing a system with a so deep and

complex knowledge is a well-known bottleneck for

knowledge-based systems (especially as regards as

the knowledge acquisition step), that can threaten the

sustainability of the approach. One main goal of

PRiSMHA is to provide a solution to solve this

problem.

3 PRiSMHA: FRUITFUL

SYNERGIES

The solution can be found by looking in two

directions:

Crowdsourcing collaborative approaches, if a

digital version of the archival resources is

available (Ashenfelder, 2015) (Beaudoin, 2015)

(MicroPasts, 2018).

Automatic Information Extraction techniques,

when full texts are available (Boschetti et al.,

2014). Note that automatic extraction techniques

from documents other than texts (images, videos,

audio recordings) are currently out of the scope of

the project.

Thus, the specific goal of PRiSMHA is to

verify/demonstrate the feasibility of a solution based

on the integration of these two approaches.

3.1 Building the Ontology

PRiSMHA relies on two modular ontologies: a

top/core ontology called HERO Historical Event

Representation Ontology), and a domain ontology,

called HERO-900. Overall, the OWL2 version of

HERO+HERO-900 counts more than 400 classes and

more than 350 properties; moreover, it is a strongly

axiomatized ontology (more than 4.000 logical

axioms).

We started from the definition of HERO,

representing the semantically rich common

vocabulary. “Common” means shared between:

The system, the users of the crowdsourcing

platform, and final users querying the digital

“smart archivist”;

Computer scientists and ontologists actually

designing and implementing the system, and

historians providing a historical, analytical

perspective on the documents.

This top-level semantic model contains concepts

such as place, time, event, organization, collective

entity, participant, different roles played in events,

etc. Table 1 shows the basic structure of HERO.

HERO is the result of the integration of an

analysis of existing models (Agora, 2018) (CIDOC-

CRM, 2018) (Raimond and Abdallah, 2007) (Doerr

et al., 2010) (van Hage et al., 2009) (Nanni et al.,

2017) (Sprugnoli and Tonelli, 2017) and the

outcomes of the dialog between computer scientists

and historians about the notion of event, its properties

(e.g., participation in events, roles played by

participants) and the relations between events (e.g.,

cause, influence).

Most of the existing models the most famous of

which is probably CIDOC-CRM are mainly

designed for representing production, preservation

and curation activities and has been employed in

several projects for describing documents types,

creators, geographical/temporal anchoring. Although

most of these models support the representation of

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

226

events and their participants, their level of detail and

granularity does not make any of them the first

choice, when the focus is the fine-grained

representation of historical events and the relations

over them outside documents. By the way, for

interoperability reasons, PRiSMHA includes

mappings between HERO top level classes/properties

and the corresponding elements in the most used

existing ontologies.

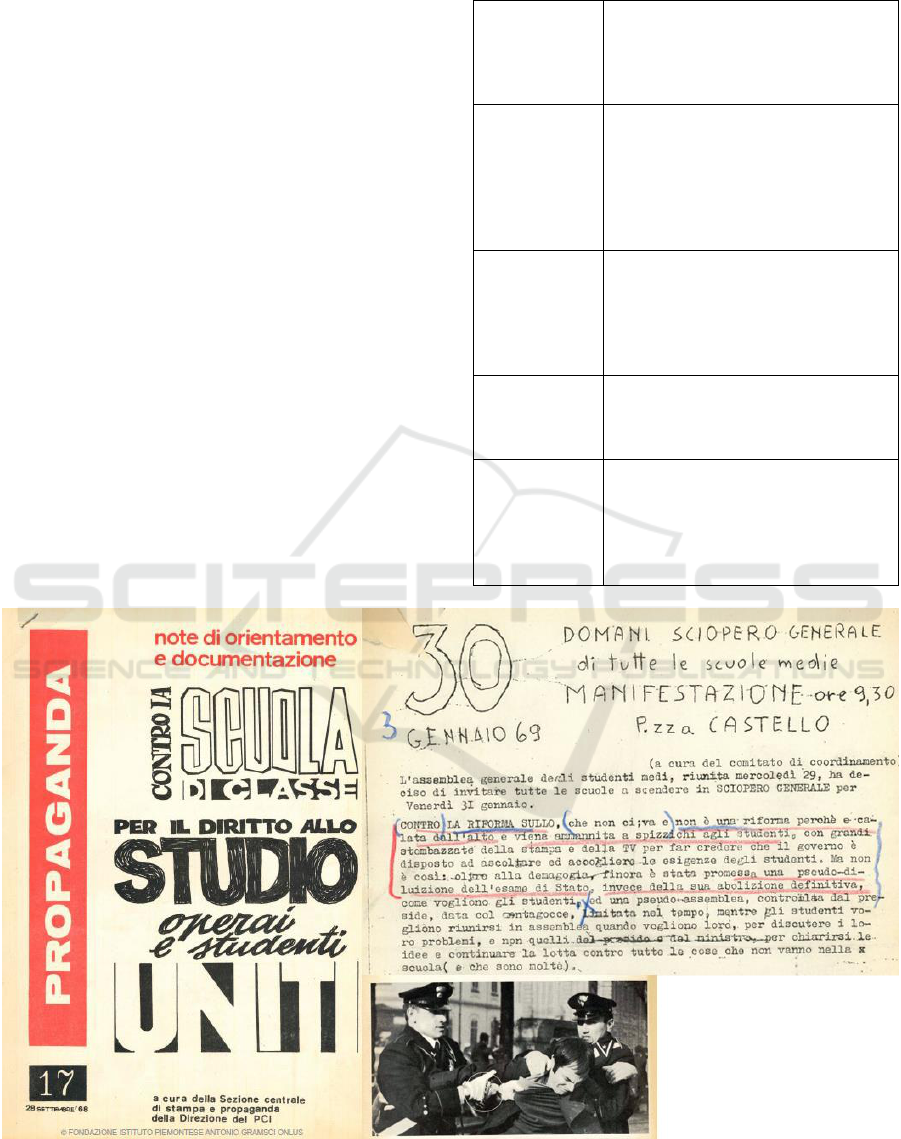

We identified the students and workers protest

during the years 1968-1969 in Italy as the specific

domain to focus on in developing our proof-of-

concept. The available documents concerning this

period are mainly non-digitized typewritten leaflet

(often containing manual annotations or drawing),

newspaper or magazine articles, and some pictures

(see Figure 1).

The historians analyzed the documents, from the

Ist. Gramsci's archives, referring to this period, in

order to select the most relevant ones with respect to

our goal. The top-level semantic model defined in

HERO has guided the analysis and subsequent

selection of documents: For each document, an

analytical card has been built, structured on the basis

of the classes and properties defined in the top-level

semantic model.

Table 1: The basic structure of HERO.

HERO-TOP

Very general classes and properties,

e.g., concepts such as abstract entity,

(non)physical object, occurrence, and

properties such as being part of,

being a sub-concept of

HERO-EVENT

General classes and properties useful

for characterizing events, e.g., event,

state, action, coming into existence,

participating in an event, playing the

role of agent in an event, occurring

at a certain time or in a certain

place, causing

HERO-ROCS

(Roles,

Organizations,

Collections,

Sets)

General classes and properties useful

for representing roles, organizations,

collections, and sets, e.g., role,

organization, being affiliated to an

organization, playing a (social) role,

being a member of a collective/set

HERO-PLACE

General classes, properties (and

individuals) useful for characterizing

places, e.g., place, building,

inside/outside, close to, ...

HERO-TIME

General classes and properties useful

for representing time intervals, e.g.,

time interval, day, date, Allen's

relations between time intervals

(preceding, following, overlapping,

...), Monday, February, UTC+1:00

Figure 1: Examples of documents concerning the students and workers protest during the years 1968-1969 [copyright:

Fondazione Istituto Piemontese Antonio Gramsci].

Fruitful Synergies between Computer Science, Historical Studies and Archives: The Experience in the PRiSMHA Project

227

Figure 2: A fragment showing the analytical cards corresponding to four documents from the archive of the Fondazione

Istituto Piemontese Antonio Gramsci (fondo Giorgina Arian Levi).

The cards, besides some fields related to archival and

practical aspects (e.g., classification data; see the first

eight columns, in grey, in Figure 2), contain fields

describing the content of the document in terms of

events, people, organizations, collectives, social

roles, and places, referred to by the document itself

(see the last six columns, with white background, in

Figure 2).

The selected documents have been digitized,

OCR-ized (when possible), and linked to the archival

record on the 9centRo platform.

Moreover, the content of the cards, built by

historians analyzing documents, has been used, in

turn, to build the domain ontology (HERO-900), i.e.,

the specific semantic model that refines HERO and

contains concepts, properties, and relations

characterizing the chosen domain (e.g., Strike,

PoliceCharge, TradeUnion, …). In building HERO-

900, this source of domain-specific information has

been coupled with domain expertise directly provided

by historians.

This “spiral” process is a concrete demonstration

of one of the most important synergies the PRiSMHA

project is based on, i.e., the synergy between the

historical perspective, the computer science

requirements, and the archivists support: We started

from the dialog between computer scientists and

historians; we built the top-level ontology; we used it

as a lens to select and analyze archival documents; we

exploited the document analysis together with

domain expertise to build the domain ontology.

Moreover, this process provided us with the

needed experience on the field that enabled us to

define a virtuous procedural model, from the paper

documents up to the digital “smart archivist”, based

on a close collaboration between universities and

cultural and historical institutions.

3.2 Building the Knowledge Base

Following an iterative methodology based on rapid

prototyping, we designed and built a first prototype of

the crowdsourcing platform, implementing a limited

number of the functionalities that had emerged from

the elicitation of user requirements and the definition

of the use cases.

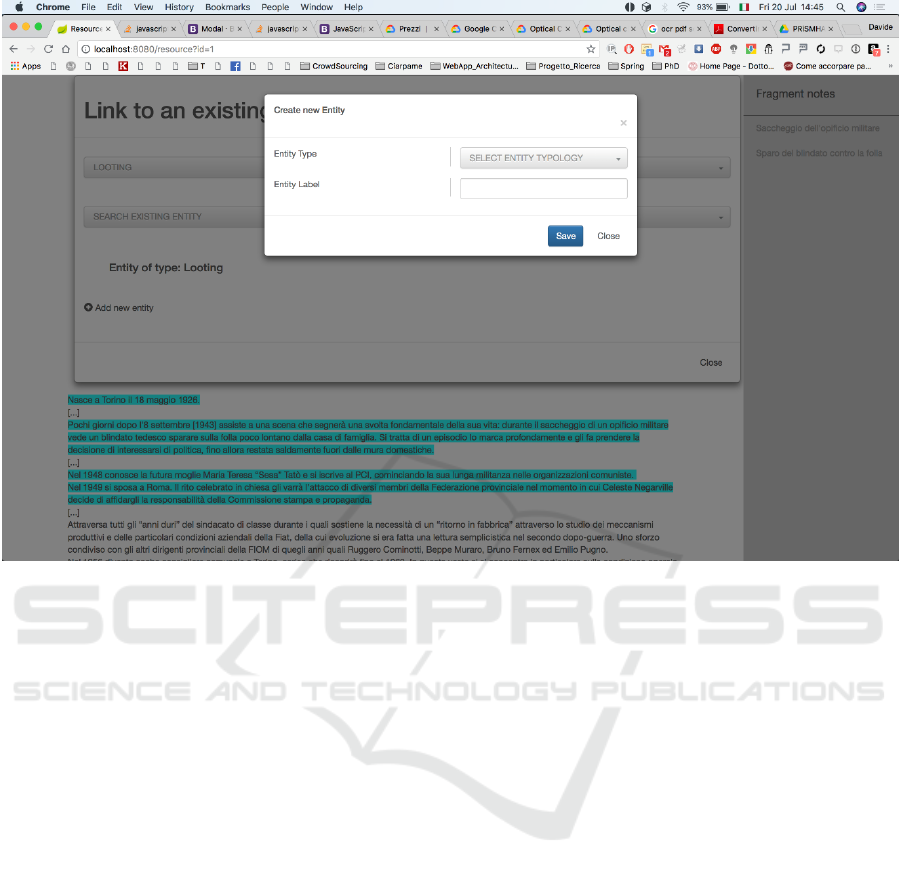

The current prototype offers a form-based User

Interface that enables users to “annotate” archival

documents with formal semantic descriptions of their

content. Figure 3 shows a screenshot of the prototype,

i.e., the page enabling the user to create a new entity

to be added to the semantic knowledge base. The

document lays in the background (relevant fragments

are highlighted); a modal window enables the user to

look for existing entities in the knowledge base or to

add a new entity by clicking on the corresponding

button: in this last case, a new modal window

overlays the previous one, thus enabling the user to

select the entity type (represented by a class in the

ontology) and provide a label for the new entity.

The process of associating formal semantic

representations to the documents is driven by the

underlying ontology HERO-900, and aims at

collaboratively building the knowledge base

(encoded as a RDF triplestore) used by the system.

Meanwhile, we are investigating the exploitation

of automatic Information Extraction on OCR-ized

archival documents. This is a very challenging issue,

due to the specific nature of texts in these documents

(Rovera et al., 2017), (Moretti et al., 2016). We aim

at studying how the output of such activity can

provide an effective support to the annotation process

on the crowdsourcing platform.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

228

Figure 3: A screenshot of the UI enabling the user to create a new entity to be added to the triplestore.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper we have presented the mid-term results

of the PRiSMHA project, that aims at contributing to

the design and implementation of a web-based system

providing an intelligent access to historical archives.

In particular, we showed the products of the fruitful

synergies between historical studies and computer

science, as well as the results of the collaboration

between research institutions and cultural centers.

Such results include a top/core ontology (HERO) and

a domain ontology (HERO-900), which together

drive the User Interface of the prototype platform

devoted to the user-generated semantic KB.

Plans for the next activities within the PRiSMHA

project encompass:

The evaluation of the mentioned prototype with

users, in order to get a feedback for implementing

the second version;

The design of an enhanced interaction model for

the crowdsourcing platform aimed at integrating

suggestions coming from the Information

Extraction tools.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by Compagnia di San

Paolo and Università di Torino within the PRiSMHA

project.

REFERENCES

Agora, 2018. Agora: eventing history.

www.ghhpw.com/agora.php. Accessed 26/11/2018.

Ashenfelder, M., 2015. Cultural Institutions Embrace

Crowdsourcing. Library of Congress. blogs.loc.gov/

digitalpreservation/2015/09/cultural-institutions-

embrace-crowdsourcing.

Beaudoin, P., 2015. Scribe: Toward a General Framework

for Community Transcription. New York Public

Library. www.nypl.org/blog/2015/11/23/scribe-

framework-community-transcription, accesses 26/11/

2018.

Boschetti, F., Cimino, A., Dell'Orletta, F., Lebani, G. E.,

Passaro, L., Picchi, P., Venturi, G., Montemagni, S.,

Lenci, A. 2014. Computational Analysis of Historical

Documents: An Application to Italian War Bulletins in

World War I and II. In LREC 2014 Workshop on

Language resources and technologies for processing

Fruitful Synergies between Computer Science, Historical Studies and Archives: The Experience in the PRiSMHA Project

229

and linking historical documents and archives –

Deploying Linked Open Data in Cultural Heritage.

CIDOC-CRM, 2018. CIDOC Conceptual Reference

Model. www.cidoc-crm.org. Accessed 26/11/2018.

Doerr, M., Gradmann, S., Hennicke, S., Isaac, A., Meghini,

C., van de Sompel, H., 2010. The Europeana Data

Model (EDM). World Library and Information

Congress: 76th IFLA General Conference and

Assembly. Gothenburg, Sweden.

Goy, A., Damiano, R., Loreto, F., Magro, D., Musso, S.,

Radicioni, D., Accornero, C., Colla, D., Lieto, A.,

Mensa, E., Rovera, M., Astrologo, D., Boniolo, B.,

D’Ambrosio, M., 2017. PRiSMHA (Providing Rich

Semantic Metadata for Historical Archives). In CREOL

2017. Contextual Representation of Objects and Events

in Language.

Goy, A., Magro, D., Rovera, M., 2015. Ontologies and

historical archives: A way to tell new stories. Applied

Ontology, 10(3-4), 331-338.

Guarino, N., Oberle, D., Staab, S., 2009. What is an

ontology?. In Staab, S., Studer, R. (eds), Handbook on

Ontologies - 2nd Edition. Springer, pp. 1-17.

Van Hage, W.R., Malaisé, V., Segers, R., Hollink, L.,

Schreiber, G., 2011. Desing and use of the Simple

Event Model (SEM). J. Web Semantics, 9(2), 128-136.

Hayes, P. J., Patel-Schneider, P. F. (eds), 2014. RDF 1.1

Semantics. W3C.

Heath, T., Bizer, C., 2011. Linked Data: Evolving the Web

into a Global Data Space. Morgan & Claypool.

Hitzler, P., Krötzsch, M., Parsia, B., Patel-Schneider, P. F.,

Rudolph, S. (eds), 2012. OWL 2 Web Ontology

Language Primer - 2nd Edition. W3C.

MicroPasts, 2018. MicroPasts: Crowd-sourcing.

crowdsourced.micropasts.org. Accessed 26/11/2018.

Moretti, G., Sprugnoli, R., Menini, S., Tonelli, S., 2016.

ALCIDE: Extracting and visualising content from large

document collections to support humanities studies.

Knowledge-Based Systems, 111, 100-112.

Nanni, F., Zhao, Y., Ponzetto, S. P., Dietz, L. 2017.

Enhancing domain-specific entity linking in DH. Book

of Abstracts of Digital Humanities, 2, 67-88.

Raimond, Y., Abdallah, S., 2007. The Event Ontology.

motools.sourceforge.net/event/event.html, Accessed

26/11/2018.

Rovera, M., Nanni, F., Ponzetto, S. P., Goy, A., 2017.

Domain-specific Named Entity Disambiguation in

Historical Memoirs, In CLiC-it'17. 4th Italian

Conference on Computational Linguistics, vol. 2006.

CEUR.

Sprugnoli, R., Tonelli, S. 2017. One, no one and one

hundred thusand events: Defining and processing

events in an inter-disciplinary perspective. Natural

Language Engineering, 23(4), 485-506.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

230