Distributed Ontology for the Needs of Disabled People

Caroline Wintergerst and Guilaine Talens

Magellan, Iaelyon School of Management, University of Lyon, UJML3, Lyon, France

Keywords: Distributed Ontology, Knowledge Organization, Domain Ontology, Heterogeneous Data.

Abstract: In French society, much help is provided to people. In the particular case of disabled people, it is quite difficult

to deal with all the different information coming from heterogeneous contexts. Such different knowledge

cannot be directly integrated, so we propose to build ontologies for each aspect. Three ontologies are built,

each from different existing sources (thesaurus, ontology, …). Disability ontology includes the medical and

social domain. Service ontology represents generic and local services. Individual needs ontology allows the

individual file description and the link with the other ontologies. Each ontology will cooperate with the others.

Then, the cooperation of these distributed ontologies must solve the problems of semantic conflicts. A

framework is proposed to build each ontology and also to manage ontology collaboration.To ensure the

representation of the guidance interactive process, we model a workflow to follow an individual file through

its successive steps. This allows better long term assistance monitoring and proves the necessity for evolutive

knowledge representation like ontologies.

1 INTRODUCTION

In France, disabled people can be helped in many

different ways, for example the adaptation of one's

home or lessons with a private teacher.

Philosophically, Doat (2013) points out the necessity

for the human society to have a good support for the

weak or people with difficulties. Every case is

particular however, there can be similar proposals. For

the people concerned and their family, it may be

baffling to know one's right. In fact, they have to

summon up lots of heterogeneous knowledge and build

a personal file to obtain help and services.

Our issue comes from two different problems.

First, to create a help file for a disabled person, we have

to manage a large amount of heterogeneous data and

documents. They cannot be described with only one

model. Some data is already described through

ontologies. Some come from thesaurus. Lastly, some

documents are not really organized. We suppose that

ontology cooperation is an efficient way to deal

judiciously with these sets of knowledge. Ontology

modeling deals with the question of how to describe in

a declarative and abstract way the domain information

of an application, its relevant vocabulary, and how to

constrain the use of the data, by understanding what

can be drawn from it (Angele & Lausen, 2004)?

So, as we also have to solve semantic conflicts

(Naiman & Ouksel, 1995) due to the cooperation of

heterogeneous sources, we choose to use the ontology

concept. The ontologies allow to recognize the

concepts contained in the different sources; these

concepts can be linked with synonymy, homonymy,

etc. relations between sources. The ontology definition

of Studer (Studer et al., 1998) based on (Gruber, 1993)

is:”An ontology is a formal, explicit specification of a

shared conceptualization”. A ‘conceptualization’

refers to an abstract model of some phenomenon in the

world by identifying the relevant concepts of that

phenomenon. ‘Explicit’ means that the type of

concepts used and the constraints on their use are

clearly defined. ‘Formal’ refers to the fact that the

ontology should be machine understandable and

excludes natural language. ‘Shared’ reflects the notion,

an ontology captures consensual knowledge, that is, it

is not private to some individuals, but shared by a

group.

Secondly, various people are present around a

disabled person. They may reason in different ways

and their words may be abstruse for each other.

Building different ontologies and processing their

cooperation will alleviate these communication

problems. We must also be conscious that the context

may be very sensitive for the people concerned.

404

Wintergerst, C. and Talens, G.

Distributed Ontology for the Needs of Disabled People.

DOI: 10.5220/0008352604040412

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineer ing and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 404-412

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Distributed ontology is a relevant framework for

the articulation between domain ontologies,

knowledge management and activity. We apply this

framework, at first, on the domain of disability. In this

framework, we develop the basis of an infrastructure

that connects information and processes. Our first goal

is the description of each ontology. The second step is

ontologies collaboration. At the end, we hope to

propose a tool for managing individual files to obtain

services linked to needs. In this paper, we propose to

follow the building of the file through different steps

using dedicated ontologies. The first step deals with the

concerned entities. We build a conceptual structure to

show the feasibility of a computer-aided process.

After a brief description of the context and some

related works, we present the different conceptual

schema of ontologies which contain knowledge.

Finally, the individual needs ontology, which manage

individual files, is described.

2 CONTEXT

2.1 Real Life Analysis

How can we associate and use together scientific

resources, individual information and rehabilitation

service documentation in the framework of an activity?

We propose a distributed ontology that articulates

different types of resources in the framework of this

activity. It is founded on personal files and its objective

is the proposition of services to a person. Of course,

this person can receive one service: in this case the

activity evaluates the relevance of this service and if it

agrees with the needs. This process is then recursive.

Our purpose is anchored on a specific activity:

guidance of people with disability to relevant services.

People, which present some disability, must

complete a file and give it to the regional house of

disabled people, in French MDPH. MDPH role is to

meet and take care of people presenting disability. It

brings together social worker, doctor, nurse to assess

the needs of the disabled person. The disabled people

and their family are guided and informed along the

development of their individual file by the MDPH.

Then, a multidisciplinary team studies the personal

objective and the specific needs of each people. This

team is the CDAPH (committee of rights and

autonomy of disabled people). It decides on the

orientation and awarding of helps and services. In fact,

the disabled person completes a form and join a

medical certificate. It is the first step of official file

submission. The MDPH studies this file with the

concerned person. After validation of this document by

the disabled person and the different members of the

team of MDPH, the CDAPH assesses this file. The

different decisions are recorded and a notification is

send to all the concerned people (the claimer, social

structures concerned by the decisions but also the

paymaster).

2.2 Preliminary Proposition

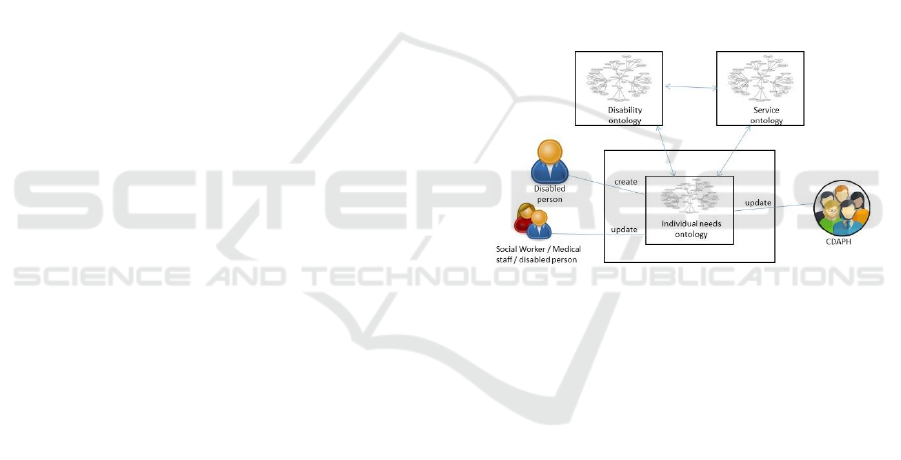

Different users interact (see Figure 1). A disabled

person creates its individual file. The information is

stored in the "individual needs ontology". To create

and select the different information, he is guided to

choose the impairments and the needs in the "disability

ontology" and the services in the "service ontology".

After, social workers and the medical staff complete

the individual file in coordination with the disabled

person. At the end, the CDAPH assign services linked

with the needs of the disabled person and the possible

places in the local services.

Figure 1: Users.

We focus on the conceptual model that allows the

organization of the different information sources:

bibliographic resources, personal files and services

description. These sources are very distinctive both in

their structure, description and organization.

It seems now established that Web, AI and

database communities have successfully used

ontologies as modeling and reasoning frameworks for

the management of complex data, providing logical

formalism or model theory (Parreiras et al. 2007).

Furthermore, ontology aids in common understanding

of domain conceptualization by providing enriched

semantics (Banerjee & Sarkar, 2016). So, we propose

a distributed ontology that represents independently

each component. Each component is structured in a

way to be used by the activity. We describe by three

ontologies this activity: the first one describes

knowledge organization for the disability, the second

one the services and the third one describes the process

of file creation leading to decision and regulation.

These three parts concern people or individuals. But

each considers distinctively the individual: for the

Distributed Ontology for the Needs of Disabled People

405

knowledge organization, it's a generic individual. For

the process, individual is the object of the activity, it's

the description of a real person.

Individual is the central notion that allows the

distribution of ontologies. Need is the central concept

that organizes the link from individual needs to

disability regarding existing needs. Need is the issue of

the deductions in the disability ontology. Activity is

based on the expression and evaluation of the needs. At

last, the process begins by a need and ends by its

satisfaction.

The disability domain is unlike medical and health

domain because it's a dynamic building that begins by

the identification of a disease or disorder and that ends

by identified disabilities. This process requires a

succession of scientific investigations, including

sociology, on the individual.

The organization of the scientific knowledge is

only one part of the model. The individual needs

ontology represents how the individual expresses his

needs in the social context of an assistance and the

rehabilitation service attribution. The last ontology

links the individual needs and the individual

rehabilitation. It represents schematically an activity.

These three ontologies manage heterogeneous types,

instances and references. They are partly inspired by

Smith and Ceusters (2010) in their methodology for

coordinated evolution of scientific ontologies.

Each ontology has a distinctive function:

Knowledge organization for disability domain

allowing to link libraries to practice, especially for

individual description,

Knowledge organization for service description in

relation to individual needs,

Workflow for file elaboration and sharing.

3 RELATED WORKS

We have chosen not to use an existing model, such as

HI-ONTO (El-Diraby & Kashif, 2005) for example,

because these models are not founded on the

association of heterogeneous entities and they

postulate the unity of the domain. In our case the

domain is itself distributed and oriented to an

individual satisfaction of a need. Disability is described

by an international classification (ICF, 2001). This has

been criticized because logical conceptual construction

is not consistent. The second knowledge organization

is the French thesaurus (French Thesaurus, 2012).

These tools organize the domain following a modular

principle. In this way they are organized by "micro-

thesaurus'' or sub-domains, (Ruggieri et al., 2001).

Some efforts are engaged to build ontology on the basis

of the classification, (Cuenot, 2015). We propose the

elaboration of a specific ontology level that maps

classes and thesaurus concepts to ontology. Our

ontology integrates active and dynamic dimensions

defined by a social characterization of disability. In this

framework, disability is considered as a phenomena

that aggregates different points of views, from

medicine to socials. We follow this principle,

considering that these different approaches are

dependent. The ordering of these dependencies allows

the consistency of the ontology and the use of the BFO

vocabulary, (Arp et al., 2015). As in Basic Formal

Ontology (BFO), (Grenon & Smith, 2004), the three

top-level categories of independent continuant,

dependent continuant and occurrent are used in our

framework.

We do not create an ontology centered on the

notion of service availability like (Ferrario & Guarino,

2009) but we deal with the building and the evolution

of an individual file through the process in our

ontologies. Our ontologies have not an upper level as

DOLCE, (Gangemi et al., 2002), but a lightweight that

focus on the needs of a specific domain: disability

domain.

Like (Santos & al.,2009), our aim is providing help

to clarify the users’demands. But our work is different

as we do not provide computer mediated services. Of

course, at the end, personal care services will be

proposed to the disabled person. Nevertheless, we help

him to build his file to claim those services.

Disability can be considered in the framework of

non-formal ontology by (Edwards et al., 2014). They

propose a social and embodied ontology that provides

a theoretical framework for situating disability in the

"ground of being'', as an encapsulation of the

limitations that are essential to the whole body-

environment. Hence, embodied ontology moves

beyond both the medical and social models of

disability, both these models seek to reject limitation in

different ways. Within the medical model, physical

limitations are considered surmountable, while the

social model rejects environmental limitations. From

an embodied perspective, both physical and

environmental limitations are essential to our

humanity.

IAO-Intel contains ontologies applied to the

explanation of data models and other terminology

resources. The terms in these ontologies are linked

together. Each ontology uses terms which are defined

in terms of other ontologies (Smith et al., 2013). In our

framework, the ontologies are also linked and we have

also different levels as IAO-Intel.

We have chosen to consider the individual as the

KEOD 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

406

basis of the relations between the different structures.

The unity is characterized at first at the instance level.

At the type level, the concept of individual is a

guarantee of generality. The second basic concept is

the need. It can be defined at the two levels too. This

realistic foundation for ontology is articulated to a

dynamic representation of a domain. These positions

have been defined by Smith and Ceusters (2010) but

have never been applied on complex domains like

disability. This domain is intrinsically built by the

articulation between a scientific knowledge, processes

and services. These considerations are evidences for

the actors but they have not been applied. Knowledge

organization stays always static without any

connection to the other dimensions of the domain: the

proposition of services and the process have never been

represented as we know. Especially, the relation

between these three dimensions has never been

conceptualized. This fact can be explained by the

distinction between library, knowledge management

and service representation.

4 GENERIC MODEL

We propose a generic model to articulate three

different information sources:

Scientific publications on disability, numerous

resources, combined to achieve the disability

ontology.

The services ontology characterizes the matching

of a personalized service with the individual needs

and society offers.

Process which attributes services to a person. This

ontology describes a workflow implying different

actors and a decision.

In opposite to monolithic domain ontology, we

have proposed a distributed ontology to capture the

different dimensions of a domain. This domain is built

on an activity: the rehabilitation of people with

disabilities. This activity requires different actors and

at first the person called individual and one objective:

the rehabilitation of this person.

The academic knowledge organization is

unsatisfying to represent a pluri-disciplinary

knowledge structure that integrates both scientific

knowledge, individual expression and the availability

of rehabilitation services in a specific location and

time.

The link between these different dimensions is

founded on the individual that is the object of the

activity. This individual has needs and the satisfaction

of these needs is the goal of the activity.

The process is the actors and files that allows the

individual expression of the need and the

representation of its evolution in time.

The process representation is intrinsically dynamic

and requires for the examination of the individual

situation a similarly logically knowledge

representation. We have postulated that the building of

the knowledge domain follows the path from a health

perspective to a particular social, individual or

contextual disability. This path is fundamental for the

characterization of a need and identification of the

tools or services that allow the satisfaction of this need.

Our aim and challenge is to manage two different

levels of abstraction. On one hand, we try to deal with

a great amount of knowledge stored in heterogeneous

resources. On the other hand, we cope with individual

information about the person's impairments and life.

We propose, then to connect this individual data with

documented and referenced information. The PROV-

Ontology is shortly described with the following: ''It

provides a set of classes, properties, and restrictions

that can be used to represent and interchange

provenance information generated in different systems

and under different contexts'' (PROV, 2013). So, we

have chosen to work with the PROV-Ontology to

manage our dual issues described above.

Our three information sources are heterogeneous

but they are interdependent. At a high level of

generality, we distinguish clearly three entities:

Individuals, Needs, Tools or Services. These

structuring entities are always situated in context.

Individual as singular entity participates to the different

ontologies:

As a categorized entity, an individual is a person

with disability.

As a person with needs, he participates to the

personalized services.

As a person that produces files and expresses its

needs for the social services, it participates to the

workflow.

The committee of the rights and the autonomy of the

disabled people called CDAPH in France allocates

services. But, it is in the "departmental house of the

disabled people'' (MDPH in France) that an individual

can find all the information and the help to fill in the

individual file. The impairments and the needs

expressed in the file are chosen respectively among

these drawn up by the thesaurus handicap (French

Thesaurus, 2012) and SERAFIN-PH nomenclature

(SERAFIN-PH, 2016).

The individual entity contains many attributes as the

birthday, profession..., and refers to the different carers

who can help him in the social context. It is the role of

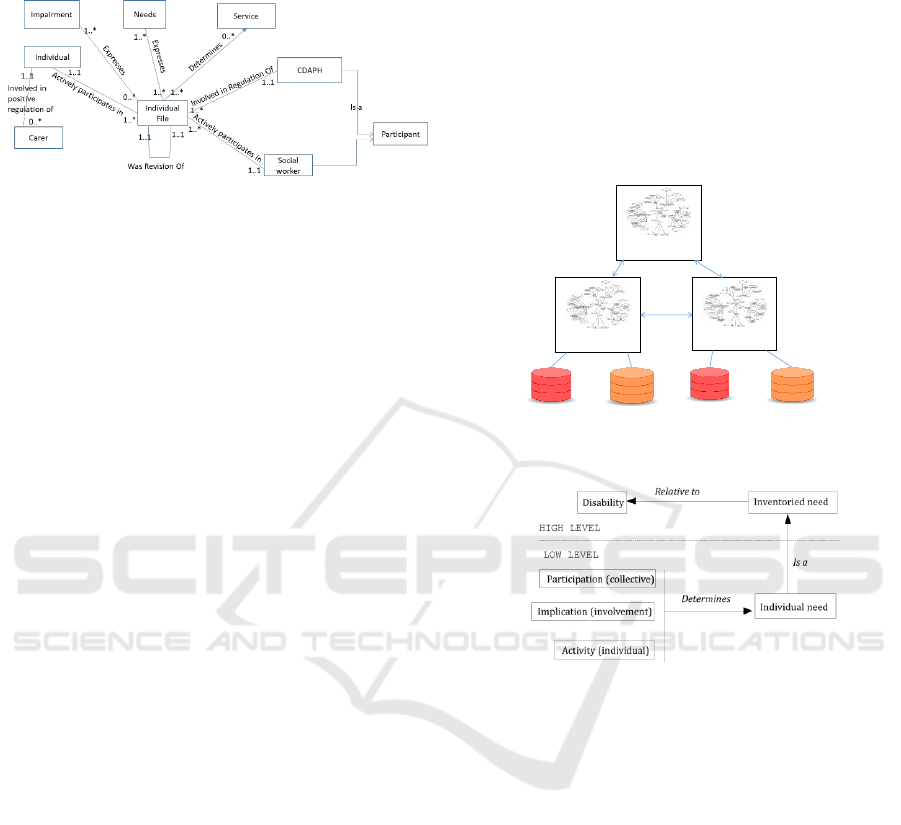

each of them which is displayed in Figure 2. The OBO

Distributed Ontology for the Needs of Disabled People

407

Relations Ontology (Oborel, 2017) has been used to

represent the relations between the concepts.

Figure 2: Individual needs Ontology.

We have chosen OBO Relations as they are meant

for biological ontologies and each relation is well

defined. The individual file describes the individual,

this one is an entity but also an actor who participates

in the building of his file. The individual must also list

his carers. The individual, with the help of the social

worker, expresses his impairments and his needs.

Finally, services are expressed. Therefore, the social

worker is also an entity and an actor. The CDAPH

determines the possible services linked with the

request and real life (places available in special

institutes, home helpers,..). It is a recursive process.

Each year, the individual updates his request and it is

re-evaluated by the CDAPH.

5 ONTOLOGIES

COLLABORATION

We are building three dependent ontologies (see

Figure 3).The individual is central in the three but is

described by categorization in the disability ontology.

Artifacts are about this individual but represent only

some relevant categories for the decision. At last, the

process associates a service devoted to this individual

considering some of its specificities.

We have not a mapping between these different

ontologies but a knowledge distribution in conformity

to action relatively to disabled people.

The disability ontology is built from different

sources (French thesaurus, international classifications

…) but also taking into account the social dimension.

It is very important to deal also with the context of the

person and not only the disability. The MDPH is the

house of handicap social sciences. National and

international scientific exchanges inside it allowed the

creation of a thesaurus (French Thesaurus, 2012). This

one in 2001 had 10992 terms. Now we reached the

4

th

version and the thesaurus contains 12825 terms. It

includes the social and psychosocial angles of the

handicap in France. It is the result of several resource

centers collaborative work in the field of handicap.

We describe a need as a relation between an

identified disability, an individual expression and a

rehabilitation process. Need has a dual definition: at a

type level, it is a relation between a disability, an

expression and a rehabilitation service. By this

information flow, we characterize how the three

ontologies are connected under the question of the

needs. A need is then defined both by the disability and

the individual expression.

Figure 3: Ontologies.

Figure 4: Need characterization.

Disability is a complex domain that can't be

reduced to disease aspects or social action. In a way to

represent the consistency of the domain, we propose

different phases to characterize the path from a disease

to a social action.

The ontology is a cognitive representation

characterized by a two levels structure (see Figure 4):

At the high level, the characterization of the person

with eventually disability. This is the global

consistency of the disability domain.

At the low level, the context of the disabled person

is segmented into a succession of situations where

the internal disease is evolved into successive

frames.

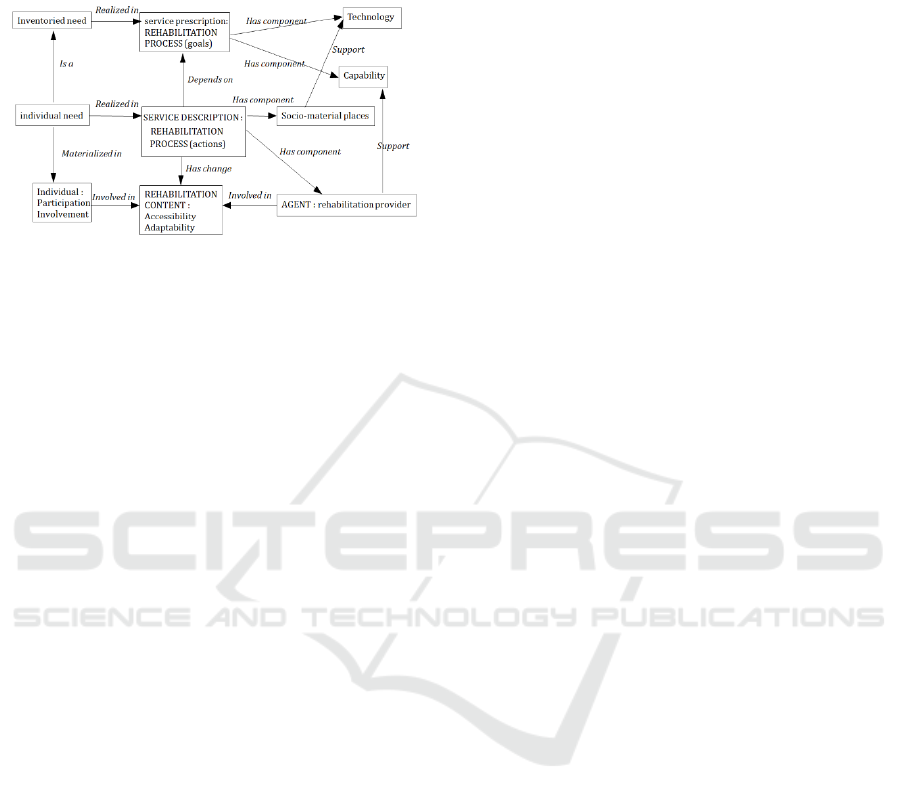

We present now, in the Figure 5, for a part, the

ontology of services. This ontology allows the

characterization of the satisfaction of the need. It

integrates some characteristics of the service ontology

like the distinction between a service prescription and

a service description. This distinction allows the link

Disability

ontology

Service

ontology

Individual

needs ontology

…..

…..

Local services

French

Thesaurus

International

classifications

SERAFIN-PH

KEOD 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

408

between the generic SERAFIN-PH nomenclature

(SERAFIN-PH, 2016) and the local organizations

presentation of services.

Figure 5: Service Ontology.

The service ontology is built from the serafin-PH

nomenclature, it’s constituted of needs nomenclature

and service nomenclature. It contains:

Need descriptions of assisted people

Service descriptions address person’s needs.

The local services are also added with the place

number in each health care facility with the free places.

The building of the disability and service

ontologies are a challenge because they are built up

using different databases or thesaurus in French and in

English. The mapping between the terms and the

heterogeneity of terms is a real complexity. The

process must find in the disability and service

ontologies the good impairments, needs and services

consistent with the needs of the concerned disabled

person and reference them in the last ontology. We

insist on the individual participation by the concept of

"rehabilitation content'' that describes the benefit of the

service.

6 WORKFLOW

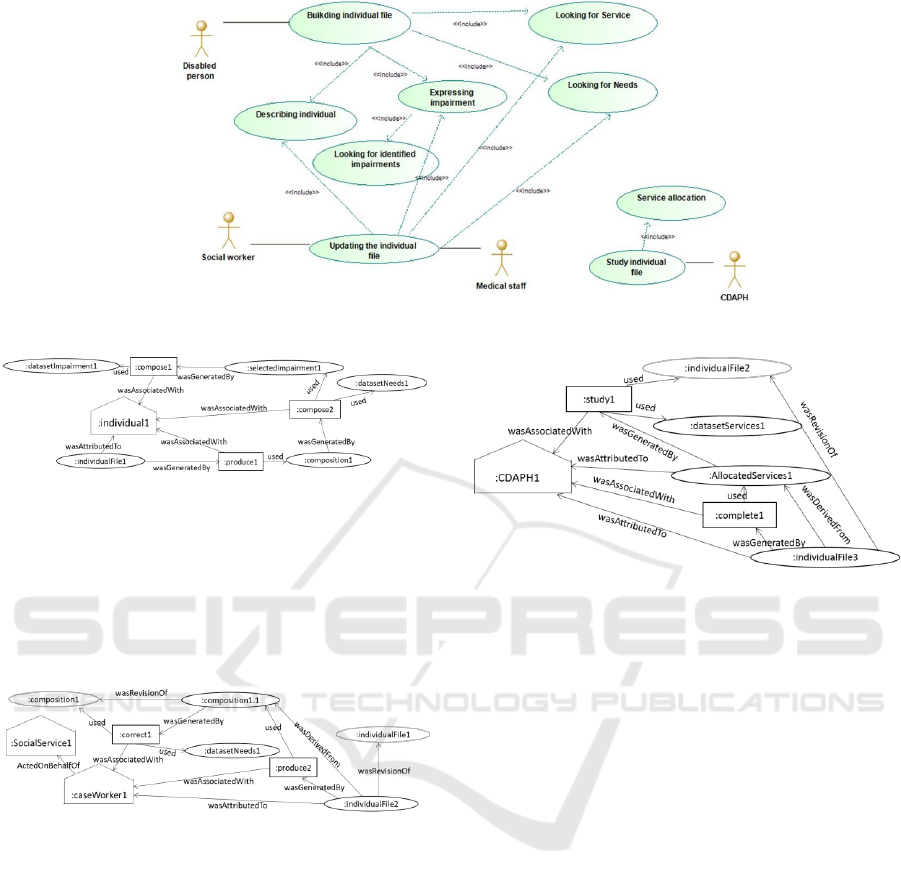

In the Figure 6, the UML use case diagram (Rumbaugh

et al., 2004) represents the functionality of the

individual file building by the disabled person. It’s

followed by its updating by the medical staff and social

worker. The disabled person describes his diseases and

his environment. He chooses the impairments and his

needs thanks to the disability ontology. In fact, many

propositions are made to him from his situation. After,

the request is evaluated by the social worker and the

medical staff and is updated in agreement with the

concerned person. For example, many services are

automatically selected in the service ontology by the

system and are proposed. The staff helps the user to

choose the right ones. Finally, the CDAPH studies the

request and offers services in connection with the

demand and with the local possibilities.

The PROV Ontology, (PROV, 2003), has been

used to describe the "individual file'' creation and

evolution. At the end, services are or not attributed to

the individual which has expressed the needs.

Prov family of documents is described in (NOTE-

PROV, 2013): “Provenance is information about

entities, activities, and people involved in producing a

piece of data or thing, which can be used to form

assessments about its quality, reliability or

trustworthiness. The PROV Family of Documents

defines a model, corresponding serializations and other

supporting definitions to enable the inter-operable

interchange of provenance information in

heterogeneous environments such as the Web.”

PROV-O contains three classes: prov:Agent,

prov:Entity, prov:Activity (PROV, 2013). The agents

are represented by pentagons in the figures; they take

act on the entities through activities. These one are

rectangles, they can generate entities but also modify,

use, … entities. These one are ovals in the figures, they

can be physical, conceptual or other.

The scenario allows describing the building of

individual files. The entities are the individual file, the

selected impairments, the needs among all the existing

ones and the attributed services. Three agents take part

in the activities : an individual which describes his

needs corresponding to his impairments, a case worker

modifies the file by adding or deleting needs relatively

to the impairments and the individual situation. Finally,

the concerned CDAPH studies the individual file and

decides the services to allocate. The different agents

are helped respectively by the disability and service

ontologies.

As you can see on Figure 7, an individual creates

his "individual file'' which contains, at the beginning,

his impairments descriptive analysis and a first needs

list. The composition activity (:compose1) uses the

impairments selected by the indivual1. This activity

automatically generates the relevant data. After,

another composition activity generates the selected

needs. Finally, the :individualFile1 is produced by

individual1. He is an agent, a person described by

attributes : age, name, profession and the carers that

can help him.

In a second step (see Figure 8), a case worker

completes the :IndividualFile1. :caseWorker1 is an

agent, a person, who works in an organization which is

itself an agent. The selected needs by individual1 are

revised and a new composition is created. A new

individual file with better expression of needs is

produced; it is a revision of the previous.

Distributed Ontology for the Needs of Disabled People

409

Figure 6: File building use case.

Figure 7: Individual file Creation.

Then, an instance of the CDAPH studies the

individualFile2 with the data set of existing services

(see Figure 9). With all this information, the allocated

services are decided. A new "individual file'' is created,

it is a revision of ":individualFile2'', allocated services

are added to it by the ":CDAPH1'''.

Figure 8: Individual file Revision.

This ":individualFile3'' is not a final one. The

individual can appeal against the CDAPH decision

and, then create an ":individualFile4'' to argue for a

new analysis for his case and rights. Furthermore, from

time to time, at least each year, a case worker will

inspect the individual and may revise his individual

file. This ":individualFileN'' will, then, be studied again

by the CDAPH. The process is gradual and iterative.

7 CONCLUSION

We have presented a first conceptual structure that

allows the organization of a domain characterized by a

process. The next step of the project will concern the

connection to the thesaurus that indexes the scientific

Figure 9: Individual file Update.

files, the characterization of the information artefacts

that compose the process and the duality composed by

the nomenclature and the available services in time,

location and actors.

The heterogeneity of the files and the modalities to

accede to their content (information extraction,

indexation, metadata) argues the strategy of a

distributed ontology.

Inside each ontology and also for the collaboration,

the problem of semantic conflicts must be solved to

insure the cohesion. (Fernández-Breis & Martiinez-

Bejar, 2002) presents a framework that allows

cooperative construction of ontologies ; various agents

work on the creation of an ontology from their

particular contributions, which are meant to be private

ontologies corresponding to each agent. In our case, the

framework must use the existing ontologies and

thesaurus and the process is not the integration but the

cooperation. It is not a framework to create a

collaborative ontology (Farquhar & al., 1997) from

others which is created but a framework for the

articulation between domain ontologies, knowledge

management and activity.

Another perspective is to help the individual with

the step of building and updating the individual file by

proposing the similar existing cases to his research.

Indeed, our framework will propose allocated services

KEOD 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

410

to an individual file, which has a similar context and

need. The characteristics of the person do not appear,

only the carer roles, the impairments, the needs and the

allocated services. It is a help to describe better an

individual file. Our tool will be useful for

administration although for the organizations involved

in the handicap field.

In our societies, people often have to build

individual file dealing with heterogeneous and

independent knowledge. Our framework may retrieve

knowledge to build ontologies. These can, then, be

used to assist people building their individual file for

any domain managing help such as the elderly or

children.

REFERENCES

Angele, J. and Lausen, G., 2004. Ontologies in F-logic. In

Handbook on Ontologies, pages 29–50.

Arp, R., Smith, B., & Spear, A. D., 2015. Building ontologies

with basic formal ontology. Mit Press.

Banerjee, S., Sarkar, A., 2016. Ontology-driven approach

towards domain-specific system design. In International

Journal of Metadata semantics and Ontologies, Vol. 11,

N°1, pp.39-60

Cuenot, M., 2015. Améliorer les cadres de référence pour le

suivi de l’application de la Convention des Nations Unies

relative aux droits des personnes handicapées: une

illustration à travers le processus de mise à jour de

l’International Classification of Functioning, Disability

and Health (ICF).ALTER-European Journal of Disability

Research/Revue Européenne de Recherche sur le

Handicap, 9(1), pp. 64-74.

Doat, David, 2013. Vers une ontologie humaine intégratrice

du handicap et de la fragilité en contexte évolutionniste

in René-Michel Roberge Volume 69, numéro 3,

Octobre 2013. Faculté de philosophie, Université Laval

et Faculté de théologie et de sciences religieuses,

Université Laval, pp.549-583

Edwards, G., Noreau, L., Boucher, N., Fougeyrollas, P.,

Grenier, Y., McFadyen, B. J. & Vincent, C., 2014.

Disability, Rehabilitation Research and Post-Cartesian

Embodied Ontologies–Has the Research Paradigm

Changed? In Environmental Contexts and Disability .

Emerald Group Publishing Limited. pp. 73-102.

El-Diraby, T. E. & Kashif, K. F., 2005. Distributed ontology

architecture for knowledge management in highway

construction. In Journal of Construction Engineering

and Management, 131(5), 591-603.

Farquhar, A., Fikes, R., & Rice, J., 1997. The ontolingua

server: A tool for collaborative ontology construction.

International journal of human-computer studies, 46(6),

707-727.

Fernández-Breis, J. T., & Martiinez-Bejar, R., 2002. A

cooperative framework for integrating ontologies.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

56(6), 665-720.

Ferrario, R., Guarino, N., 2009. Towards an Ontological

Foundation for Services Science, In D. Fensel, and P.

Traverso (eds.), Proceedings of Future Internet

Symposium 2008, Springer Verlag, Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, vol. 5468, Berlin Heidelberg,

pp. 152-169.

French Thesaurus, 2012. http://mssh.ehesp.fr/wp-

content/uploads/2012/10/THESAURUS-

HANDICAP_FINAL_V_3.pdf

Gangemi, A., Guarino, N., Masolo, C., Oltramari, A.,

Schneider, L., 2002. Sweetening Ontologies with

DOLCE In Lecture Notes in Computer Science book

series, LNCS, volume 2473. pp. 223-233

Grenon P, Smith B, 2004. SNAP and SPAN: towards

dynamic spatial ontology. Spatial Cognition and

Computation. 4:1 pp. 69–103

Gruber T.R., 1993. A translation approach to portable

ontologies, In Knowledge acquisition, Vol. 5, n°2, pp.

199-220.

ICF, 2001. International Classification of Functioning,

Disability and Health. World Health Organization

Geneva http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/

42407/7/9241545429_tha%2Beng.pdf

Naiman C., Ouksel A. M., 1995. A classification of semantic

conflicts in heterogeneous information systems, Journal

of organizational computing, 5 (2), pp. 167-193.

NOTE-PROV, 2013.http://www.w3.org/TR/2013/NOTE-

prov-overview-20130430/

Oborel, 2017. https://raw.githubusercontent.com/oborel/

obo-relations/master/ro.obo

Parreiras, F.S., Stabb, S. and Winter, A., 2007. On marrying

ontological and metamodeling technical spaces, Paper

presented in 6th Joint Meeting on European Software

Engineering Conference, 3–7 September, Dubrovnik,

Croatia, pp.439–448.

PROV, 2013. https://www.w3.org/TR/prov-o/

Ruggieri, A. P., Elkin, P. L., Solbrig, H. & Chute, C. G.,

2001. Expression of a domain ontology model in unified

modeling language for the World Health Organization

International classification of impairment, disability, and

handicap, version 2. In Proceedings of the AMIA

Symposium.

Rumbaugh, J., Jacobson, I., & Booch, G., 2004. Unified

modeling language reference manual, the. Pearson

Higher Education.

Santos, S., Olavo, L., Guizzardi, G., Pires, L.F. and Sinderen,

M.V., 2009. From user goals to service discovery and

composition, In Heuser, C.A. and Pernul, G. (Eds):

Advances in Conceptual Modeling – Challenging

Perspectives: Proceedings of the ER 2009 Workshops

(LNCS), Vol. 5833, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg,

Germany, pp.265–274.

SERAFIN-PH, 2016 Nomenclatures, besoins et prestations

détaillées. Services et établissements : réforme pour une

adéquation des financements aux parcours des personnes

handicapées. http://solidarites-

sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/nomenclatures_serafinphdetaille

es_mars_16.pdf

Smith, B., Malyuta, T., Rudnicki, R., Mandrick, W., Salmen,

D., Morosoff, P., Duff, D. K., Schoening, J., Parent, K.,

Distributed Ontology for the Needs of Disabled People

411

2013. IAO-Intel: An Ontology of Information Artifacts

in the Intelligence Domain In K. B. Laskey and P. C. G.

Costa (Ed.) Proceedings of the Eighth International

Conference on Semantic Technologies for Intelligence,

Defense, and Security, Fairfax, VA, (STIDS 2013),

CEUR, vol. 1097, 33-40

Smith, B., Ceusters, W., 2010. Ontological realism: A

methodology for coordinated evolution of scientific

ontologies In Journal Applied Ontology, Volume 5,

Issue 3-4, IOS Press Amsterdam, The Netherlands,

pp. 139-188.

Studer R., Benjamins D., Fensel D., 1998. Knowledge

Engineering: Principles and Methods, In IEEE

Transactions on Data and Knowledge Engineering, Vol.

25, Issue 1-2, pp. 161-197.

KEOD 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

412