Measuring Individuals’ Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour on

Specific Ocean Related Topics

Conor McCrossan and Owen Molloy

National University of Ireland, University Road, Galway, Ireland

Keywords: Ocean Literacy, Ocean Knowledge, Ocean Attitude, Ocean Behaviour, Micro-plastics, Coastal Tourism,

Sustainable Fisheries.

Abstract: In order to measure the effectiveness of Ocean Literacy (OL) tools we can measure people’s knowledge of,

and attitude and behaviour towards, specific ocean-related topics, both before and after their use of the tool.

The research described in this paper aims at development of more accurate, focused survey tools. In

particular we are interested in ensuring that we can accurately assess knowledge on specific topics, rather

than assessing broad ocean literacy levels. Surveys were created to measure the levels of knowledge,

attitude, and behaviour of university students. The topics which the surveys focused on were micro-plastics,

coastal tourism, and sustainable fisheries. The knowledge, attitude, and behaviour questions in the surveys

are based on work carried out as part of the H2020 ResponSEAble project on Ocean Literacy. The results

show that while the students have a high level of pro-ocean-environmental attitude, their existing behaviour

is low to medium, and their future intended behaviour is at a higher level than their existing behaviour. The

findings provide useful pointers on how to improve both the ocean literacy tools (no statistically significant

correlation between knowledge and either attitude or behaviour) as well as the design of the survey and

questions themselves.

1 INTRODUCTION

It seems that nearly every day we see news articles

relating the urgency of addressing issues regarding

the health of our oceans and the welfare of the

species that inhabit them. In terms of the life span of

the Earth, and the current ocean ecosystems,

humanities impact has been relatively brief, but

devastating. Phenomena such as ocean acidification,

bleaching of corals, plastics, overfishing and

warming can all be directly related to human

activity. From deep ocean trenches to remote

Antarctic seas, we can find evidence of our impact

on the ocean environment (Ocean Plastic, 2017).

Rather than blindly addressing symptoms, it is

vital to address causes of problems. Intelligent

solutions require that we understand the complex

systems involved in the interplay between humans

and the oceans. The processes and activities

involved must be understood in order to target

interventions such that they have significant impact.

Complex supply chains often involve multiple

activities and human actors (Trienekens et al., 2012),

each with different requirements in terms of

knowledge, influence and ability to act. For

example, individual tourists and planning officers

will have very different perspectives, knowledge and

potential impact in terms of addressing problems

caused by mass coastal tourism. The recent efforts to

prevent plastic microbeads from entering our oceans

and ecosystems is a good example (Xanthos and

Walker, 2017). Social media campaigns and

awareness-raising helped to change individual

consumer’s attitude and behavior, while

governments took notice of the problem and

legislated to ban microbeads from cosmetics

products (Girard et al., 2016). Meanwhile, cosmetics

producers are removing microbeads from their

products and replacing them with sustainable

alternatives (Microbead Ban, 2018).

In this paper we examine the measurement of

Ocean Literacy (OL) as a means of assessing the

effectiveness of OL initiatives and tools. This

research can also be applied to measurement in other

areas e.g. Environmental Literacy. An approach to

measure environmental knowledge, attitude, and

behaviour would involve chosing specific topics

related to environmental literacy and creating

surveys on those topics. Examples of environmental

McCrossan, C. and Molloy, O.

Measuring Individuals’ Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour on Specific Ocean Related Topics.

DOI: 10.5220/0008353003250332

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 325-332

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

325

literacy topics which could be chosen are air

pollution and energy use. The Literature Review

section of this paper looks at existing measurement

approaches (typically surveys) in relation to OL and

the data analysis procedures applied. We then

describe our work in designing surveys to assess OL

on specific topics, rather than large topics covering

broad OL. The Methodology section describes the

actions taken to create our surveys, and gather the

data. The Data Analysis and Results section

describes the analytical techniques applied to the

data, such as Rasch analysis, comparison between

current and future behavior, and distractor analysis.

The Discussion section discusses the findings from

the data analysis and the Conclusion section contains

the conclusions drawn from this research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Measurement of Ocean Literacy

Existing research typically derives the definition of

Ocean Literacy (OL) or Ocean Environmental

Awareness from the broader concept of

environmental awareness (Umuhire and Fang,

2016). It includes a person’s ability to realize an

existing connection between human activities and

the state of the ocean, and a person’s attitude

towards a safe and healthy marine environment. The

understanding of the impact of human activities was

the subject of a European-wide survey of societal

awareness and perceptions about marine litter

(MARLISCO project).

It is desirable for people to have a higher level of

knowledge and understanding in relation to the

ocean, as well as improvements in attitudes,

behaviours, and how we communicate on ocean

issues with other people. By improving knowledge,

attitude, and behaviour in relation to the ocean,

people are empowered to grasp complex issues and

make informed decisions regarding their behaviour,

while also communicating on them with other

people and institutions.

The objectives of this research are to (i)

investigate ocean environmental awareness related

dimensions, (ii) find what approaches are taken to

measure these dimensions, and the data analysis

procedures that can be used to generate useful

information from responses to questionnaires and

surveys, (iii) create and administer surveys to

measure the levels of knowledge, attitude, and

behaviour of students, and (iv) use the survey

response data to identify weaknesses in the questions

with respect to the survey goals.

This last objective (iv) helps us to explore the

difficulties involved in measuring the effectiveness

of ocean literacy tools and interventions, especially

where they relate to quite narrow and specific topics

such as micro-plastics, coastal tourism, and

sustainable fisheries.

The five essential components of environmental

literacy outlined by the Environmental Literacy

Ladder (ELL, 2007) are Awareness, Knowledge,

Attitudes, Skills, and Collective Action. Each of the

components are seen as steps on a ladder towards

environmental literacy, as shown in Figure 1.

However, rather than viewing the levels possessed

by an individual as steps on a ladder, it is more

realistic to view it as a combination of ocean related

dimensions. Using the ocean related dimensions, the

levels possessed by a person can be measured as a

combination of their level of knowledge related to

ocean, the extent to which their attitude is pro-

ocean-environmental, and how environmentally

friendly their behaviour is in relation to the ocean. In

our framework, awareness is defined as the basic

knowledge that a situation, problem or concept

exists. Knowledge is what a person knows about an

ocean related topic and the links between topics.

Attitude is related to a level of agreement with or

concern for a particular position. Communication is

the extent to which a person communicates with

others, such as family and peer groups, on ocean

related topics. Behaviour relates to decisions,

choices, actions, and habits with respect to ocean

related issues.

Figure 1: The Environmental Literacy Ladder.

Some of the existing approaches to measuring

knowledge and awareness related to the ocean

include the Survey of Ocean Literacy and

Experience (SOLE) (Greely, 2008) and the

International Ocean Literacy Survey (IOLS)

(Fauville et al., 2018). Both surveys include similar

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

326

questions related to general knowledge about the

ocean, e.g. how much of the earth is covered by the

ocean, ocean circulation, the depth of the ocean,

ocean resources, and the supply of salt to oceans by

rivers. Having surveys on specific topics helps with

the assessment of the impact of interventions which

are targeted at specific topics. It is important to note

that it is difficult to create a survey on specific topics

because there may only be a small number of

questions, on specific topics, that a person may

know the correct answer to and it may also be

difficult to establish a level of consistency of

responses on a narrow range of questions.

2.2 Existing Data Analysis Approaches

Rasch analysis is an approach used to calculate a

person’s knowledge (called their “person ability”),

item difficulties, error values, and fit values from

responses to a set of questions. These values are then

used to give an indication of how each respondent

performed and the level of difficulty associated with

each question. The level of error and fit associated

with each question can be used to indicate questions

which can be improved. The Rasch model is based

on the idea that useful measurement involves

examination of only one human attribute at a time

and it provides a mathematical framework against

which test developers can compare their data (Bond

and Fox, 2007).

3 METHODOLOGY

The 3 surveys created as part of this research are

based on 3 of the key story topics which are part of

the ResponSEAble (2015) project. The key story

topics are Micro-plastics (2018), Coastal Tourism

(2018), and Sustainable Fisheries (2018). Each of

the surveys contain the following 5 sections: (i)

general respondent information e.g. country, city,

age range, (ii) questions related to the knowledge

possessed by the respondent regarding the topic, (iii)

questions on the attitude of the respondent towards

the topic, (iv) questions on the current behaviour of

the respondent in relation to the topic, and (v) the

future intended behaviour of the respondent in

relation to the topic.

The surveys were created and administered

online using Google Forms (2018). Google forms

provide a way of creating and administering online

surveys, and receiving and analysing the responses

to the surveys. Bitly (2018) links were used to

provide access to the surveys and all of the

respondents to the surveys were undergraduate

university students. The students surveyed were not

involved in the ResponSEAble project and had not

used any of the tools created as part of the project.

4 DATA ANALYSIS AND

RESULTS

4.1 Descriptive Analysis

There were a total of 184 responses: 70 to the micro-

plastics survey, 69 to the coastal tourism survey, and

45 to the sustainable fisheries survey. The

respondents to the surveys were Irish university

students, and their age range was between 18 and 24

years. 17 of the 70 respondents to the micro-plastics

survey used the link to view the micro-plastics

correct answers, 9 of the 69 respondents to the

coastal tourism survey used the associated correct

answers link, and 13 of the 45 respondents to the

sustainable fisheries survey used the associated

correct answers links. So, the percentage of

respondents who used the associated correct answers

links for the micro-plastics, coastal tourism, and

sustainable fisheries was 24.3%, 13%, and 28.9%,

respectively.

4.2 Correlation Analysis

The correlation analysis of the relationship between

attitude and behaviour in relation to the surveys

shows that a correlation does exist. The Pearson

correlation r-value for the correlation between

attitude and behaviour for the micro-plastics

responses was found to be 0.495 with the correlation

significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). The r-value

for the correlation between attitude and behaviour

for the coastal tourism responses was found to be

0.442 with the correlation significant at the 0.01

level (2-tailed). The r-value for the correlation

between attitude and behaviour for the sustainable

fisheries responses was found to be 0.296 with the

correlation significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). No

statistically significant correlation was found

between knowledge and attitude or knowledge and

behaviour for each of the 3 surveys.

The internal consistency of the questions used to

measure the attitudes and behaviour of respondents

was measured by performing correlations between

each of the questions measuring attitude and each of

the questions measuring behaviour. A statistically

significant correlation was found for all of the

Measuring Individuals’ Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour on Specific Ocean Related Topics

327

pairings except for the pairing between micro-

plastics behaviour questions 15 and 16, and the

pairing between sustainable fisheries attitude

questions 11 and 12.

4.3 Reliability Analysis

The Cronbach’s alpha statistical test was used to

check the internal consistency of the attitude and

behaviour questions.

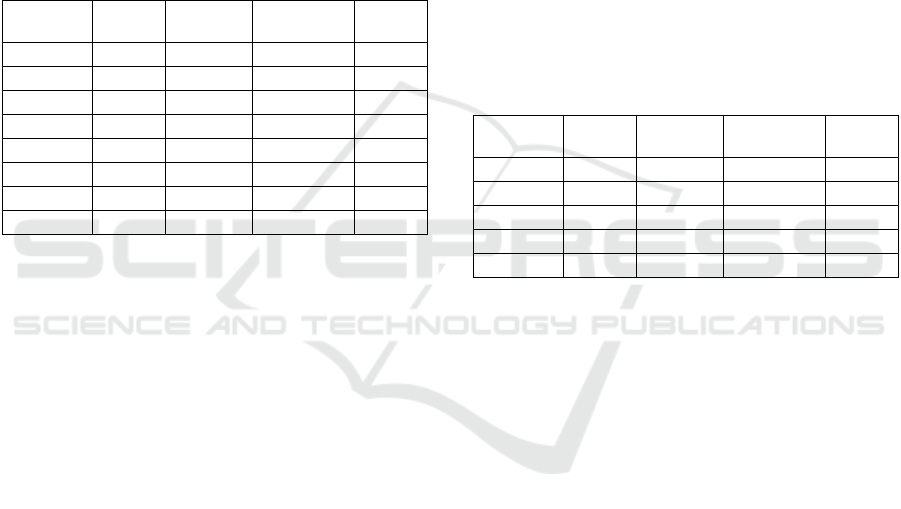

Table 1: Mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha

if item deleted for micro-plastics attitude and behaviour

questions.

Question

number

Mean

Standard

deviation

Cronbach’s alpha

if item deleted

Q 9

8.19

1.77

0.536

Q 10

8.07

1.82

0.565

Q 11

8.6

1.62

0.919

Q 12

5.63

2.74

0.741

Q 13

3.56

2.92

0.751

Q 14

4.79

3.09

0.724

Q 15

5.37

2.96

0.782

Q 16

8.13

2.24

0.834

Table 2: Mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha

if item deleted for coastal tourism attitude and behaviour

questions.

Question

number

Mean

Standard

deviation

Cronbach’s alpha

if item deleted

Q 6

7.25

2.11

0.655

Q 7

6.71

2.34

0.706

Q 8

8.64

1.79

0.800

Q 9

7.16

2.93

0.876

Q 10

3.94

3.19

0.837

Q 11

3.07

2.92

0.821

Q 12

3.61

3.17

0.810

Q 13

4.52

3.30

0.856

Table 3: Mean, Standard Deviation, and Cronbach’s Alpha

if Item Deleted for Sustainable Fisheries Attitude and

Behaviour Questions.

Question

number

Mean

Standard

deviation

Cronbach’s alpha

if item deleted

Q 10

8.49

1.34

0.358

Q 11

7.78

1.99

0.427

Q 12

7.80

2.19

0.744

Q 13

3.11

3.14

0.818

Q 14

2.49

3.27

0.849

Q 15

4.76

3.40

0.842

Q 16

3.13

3.24

0.821

Q 17

4.87

3.35

0.892

The resulting Cronbach’s alpha value for the attitude

questions in the survey on micro-plastics was 0.783,

coastal tourism was 0.8, and sustainable fisheries

was 0.604. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the

behaviour questions in the survey on micro-plastics

was 0.808, coastal tourism was 0.869, and

sustainable fisheries was 0.873. Tables 1, 2, and 3

show the question number, mean, standard

deviation, and the “Cronbach’s alpha if item

deleted” for each of the attitude and behaviour

questions in the 3 surveys.

4.4 Rasch Analysis

Person abilities are calculated by performing a log

odds (logit) transformation on the percentage of

questions a respondent has answered correctly

(Bond and Fox, 2007). For example, to calculate the

logit value for a percentage correct score of 64%, we

calculate the odds of 64 to 36 by dividing 64/36, and

then get the natural log of the result, which is +0.58

logits. The item difficulties are calculated similarly

and are based on the percentage of times a question

is answered correctly. The error value is an

indication of the accuracy of the Rasch measure for

a person ability or item difficulty and the error

values are related to how many items or persons are

positioned in the same area on the Rasch logit scale.

The fit value for items is an indication of the extent

to which a question appears to be measuring the

unidimensional topic and the fit for a person can

give an indication of unusual sequences of responses

e.g. a person guessing the answers to questions. The

“Outfit Zstd” values reported in tables 4, 5, and 6 are

standardized fit statistics which are the result of t-

tests of the hypothesis “Does the data fit the model

(perfectly)?” (Outfit, 2018).

Tables 4, 5, and 6 show the Rasch estimates for

the knowledge questions in the surveys. The tables

are ordered by question difficulty with the most

difficult question at the top. The “Question number”

column shows the number of the question used in

the survey. The “Total score” column contains the

number of respondents who answered the question

correctly. The “Measure” column contains the logit

value which gives an indication of the difficulty of

the question. The “Standard Error” column shows

the error related to the Rasch measurement and the

“Outfit Zstd” is the level of fit associated with the

Rasch measurement.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

328

5 DISCUSSION

The results of the descriptive analysis shows that the

survey respondents have a slightly higher level of

knowledge about sustainable fisheries (mean

51.85%) when compared to knowledge of micro-

plastics (mean 48.93%). The level of knowledge

possessed by the respondents with regard to coastal

tourism is the lowest at 39.71%. The respondents to

the sustainable fisheries survey have the highest

percentage (28.9%) for viewing the correct answers

to the knowledge questions, followed by the

percentage (24.3%) of respondents who viewed the

correct answers to the micro-plastics knowledge

questions, and the percentage who viewed the

correct answers to the coastal tourism knowledge

questions is the lowest at 13%.

The mean scores for the attitude questions in the

3 surveys are similar with the attitude score for

micro-plastics the highest at 8.29, followed by

sustainable fisheries at 8, and coastal tourism with

the lowest at 7.53. The mean scores for the current

behaviour responses were highest for micro-plastics

(5.49), followed by coastal tourism (4.46), and

sustainable fisheries had the lowest (3.67). The mean

scores for future behaviour are all higher than the

scores for current behaviour with the score for

micro-plastics (6.9) the overall highest, and similar

mean scores for sustainable fisheries and coastal

tourism at 5.78 and 5.71, respectively. A comparison

of the results of the current and future behaviour

questions shows that, in general, respondents intend

to improve their behaviour in the future.

5.1 Correlations

A medium correlation was found between attitude

and behaviour for the responses to the surveys. The

Pearson correlation r-value of 0.224 found by Yoon

Fah and Sirisena (2014) for the relationship between

environmental attitudes and environmental

behaviours is slightly lower than the r-value of 0.296

found in this research for the relationship between

attitude and behaviour with regard to sustainable

fisheries. The r-values for attitude and behaviour for

the micro-plastics and coastal tourism surveys are

higher at 0.495 and 0.442, respectively. Michalos et

al. (2017) found an r-value of 0.35 for attitudes and

behaviour towards sustainable development which is

slightly higher than the r-value found in this research

for the same relationship related to sustainable

fisheries. One of the behaviour questions in our

sustainable fisheries survey relates to supporting

campaigns that tell people to eat seafood that is

sustainably sourced. There is no attitude question in

the sustainable fisheries survey which relates to

attitude towards supporting campaigns. This could

be an indication of why the r-value for the

correlation between the attitude and behaviour

questions, in the sustainable fisheries survey, is the

lowest.

The reason why no significant correlation was

found between knowledge and attitude or knowledge

and behaviour could be related to the quality of the

questions. If the knowledge questions were more

aligned with measuring knowledge related to the

specific topics being measured in the attitude and

behaviour questions, a significant correlation may

exist. One of the coastal tourism attitude questions

measures how worried respondents are about the

effects of coastal tourism activities on the marine

environment. Adding a knowledge question to the

survey which tests knowledge related to coastal

tourism activities may help to identify the

knowledge which relates to a high level of pro-

ocean-environmental concern in relation to coastal

tourism activities. An example of such a question

would be “How does the activity of cleaning

seaweed from a beach impact the coastal

environment?” Care should be taken to ensure that

aligning the knowledge questions with the attitude

and behaviour questions will not constrain the

measurement too much and will not create questions

that are too difficult.

5.2 Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha values for the attitude and

behaviour question in the surveys show an

acceptable to good reliability except for the attitude

questions in the sustainable fisheries survey. The

Cronbach’s alpha value for the attitude questions in

the sustainable fisheries survey was 0.604. This

value could be increased to 0.744 if attitude question

12 was removed from the survey, as shown in table

3. Question 12 in the sustainable fisheries survey is

related to both the benefit to the marine environment

and the fishing industry of buying and eating

seafood that is labelled sustainable. This question

could be improved by dividing it into 2 questions,

one which relates to the benefit to the marine

environment and another which relates to the fishing

industry.

5.3 Rasch Estimates

The Rasch analysis of the knowledge questions

(table 4) in the micro-plastics survey shows that the

Measuring Individuals’ Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour on Specific Ocean Related Topics

329

most difficult question was question 5 “Select

products which might have contained micro-beads in

the past” and the least difficult question was

question 7 “Where does the majority of our plastic

waste end up?”. The respondents and questions are

grouped towards the centre of the logit scale in the

Rasch person-item map which indicates that the

questions are not measuring the upper and lower

respondent abilities. The Rasch person-item map

provides a visual representation of the positioning of

person abilities and item difficulties in relation to

each other along a vertical logit scale (Bond and

Fox, 2007).

Table 4: Rasch estimates for micro-plastic survey

knowledge questions.

Question

number

Total

score

Measure

Standard

Error

Outfit

Zstd

Q 5

17

1.34

0.31

-1.0

Q 4

31

0.23

0.27

-0.3

Q 3

32

0.15

0.27

-0.5

Q 1

33

0.08

0.27

-1.4

Q 8

34

0.01

0.26

1.7

Q 2

37

-0.20

0.26

4.0

Q 6

38

-0.27

0.27

-1.3

Q 7

52

-1.35

0.30

-0.5

The error associated with each of the questions is

low due to the fact that there are a lot of respondents

grouped at the same logit level as the questions. The

Oufit Zstd value for question 2 is 4.0 which is well

outside the acceptable range of -2 to 2. This means

that question 2 does not fit with the

unidimensionality of the micro-plastics survey.

Question 2 is “Which of the face wash ingredients

shown might be micro-plastics?” An image and a list

of options to choose from are provided to the

respondent. The correct answer to the question is a

single option but the format of the question allowed

the respondent to choose multiple options. This may

explain why question 2 had poor fit in the Rasch

analysis. To improve the fit of this question the

format of the question could be changed to only

allow the respondent to choose one option. The rest

of the knowledge questions in the micro-plastics

survey have Oufit Zstd values which are within the

acceptable range. Improving the set of micro-plastic

knowledge questions, with a view to making them a

more effective scale to measure the levels possessed

by respondents, would involve creating more

knowledge questions that are more difficult and less

difficult. These new questions could be combined

with the existing questions, the survey could then be

administered to another cohort, and Rasch analysis

could be used to check the improvement of the

questions as a scale to measure micro-plastic

knowledge.

The Rasch analysis of the coastal tourism

knowledge questions (table 5) shows that the most

difficult question is question 3 “Please choose the

main effects of coastal development from the list

below” and the least difficult question is question 1

“The picture below shows a paradise beach in the

middle of summer. There is an artificial rock barrier

in front of the beach. What is the function of the

artificial rock barrier?” The person-item map shows

that the questions are spread out along the logit scale

with questions 2, 5, and 1 measuring ability below

the zero logit point and questions 3 and 4 measuring

abilities above the zero logit point. The zero logit

point on the logit scale is the mean point of the item

difficulty estimates (Bond and Fox, 2007).

Table 5: Rasch estimates for coastal tourism survey

knowledge questions.

Question

number

Total

score

Measure

Standard

Error

Outfit

Zstd

Q 3

3

3.01

0.62

-0.4

Q 4

18

0.59

0.31

0.7

Q 2

32

-0.60

0.28

-0.1

Q 5

32

-0.60

0.28

-1.6

Q 1

52

-2.40

0.35

2.9

The error associated with the Rasch measure for

each of the respondents is larger than the error

associated with the items which is due to the fact

that there are only 5 coastal tourism knowledge

questions and they are spread out along the logit

scale. To increase the effectiveness of the coastal

tourism knowledge questions, more knowledge

questions could be created to measure the levels of

knowledge in between the existing knowledge

questions. As well as being the least difficult

question, question 1 is also the question with an

Outfit Zstd value of 2.9 which is outside the

acceptable range of -2 to 2. The reason question 1

does not appear to fit with the measurement of

respondents’ knowledge related to coastal tourism

may be due to the fact that question 1 is a question

more related to coastal erosion than coastal tourism.

To improve the fit of this question, it would need to

be changed to focus more on coastal tourism.

The Rasch analysis of the sustainable fisheries

knowledge questions (table 6) shows that the most

difficult question is question 1 “What is the kind of

fishing shown in the image below?” and the least

difficult question is question 5 “The picture below

shows a Cod (Gadus morhua) fish. Where does the

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

330

Cod species live?” It would be interesting to

establish why the respondents scored so highly on

this question; perhaps due to their proximity to the

North Atlantic. As such it might highlight the

importance of location-specific surveys based on

what is considered common knowledge. It also

highlights its relative lack of usefulness as a

discriminator.

Table 6: Rasch estimates for sustainable fisheries survey

knowledge questions.

Question

number

Total

score

Measure

Standard

Error

Outfit

Zstd

Q 1

2

3.59

0.76

-0.2

Q 8

14

0.91

0.36

0.7

Q 7

23

-0.11

0.33

1.0

Q 2

25

-0.33

0.33

-0.2

Q 9

25

-0.33

0.33

2.1

Q 4

27

-0.55

0.33

-0.6

Q 6

29

-0.77

0.34

-0.7

Q 3

31

-1.01

0.35

0.3

Q 5

34

-1.40

0.37

-0.3

The person-item map for the sustainable fisheries

knowledge questions shows that most of the

questions are grouped below the zero logit point

which means that they are providing measurements

of respondents with medium to low knowledge

levels. Questions 1 and 8 are the only questions

above the zero logit point. Improving the set of

sustainable fisheries knowledge questions as a scale

to measure knowledge related to sustainable

fisheries would involve creating more knowledge

questions to measure those respondents with

medium to high knowledge related to sustainable

fisheries. The positioning of the respondents with

medium to high knowledge of sustainable fisheries

has a larger error than the positioning of those with

medium to low knowledge. This is due to the fact

that there are less questions in the medium to high

knowledge section. The “Outfit Zstd” value for

question 9 is 2.1 which is just outside the acceptable

range for fit. Question 9 relates to the percentage of

the global population that depends on the ocean for

food. A way of attempting to improve this question

could involve adding more specific information to

the wording of the question.

5.4 Question Distractors

The distractor analysis of the micro-plastics

knowledge questions indicated that questions 4 and

7 could be improved. Question 4 is “Sunlight can

degrade plastics in the ocean: true or false?” More

respondents chose the incorrect (false) answer than

the correct answer. This question could be improved

by adding a third option to allow the respondent to

indicate if they are unsure about the answer.

Question 7 is “Where does the majority of our

plastic waste end up?” and less than 5% of

respondents chose the options “Burned for energy”

and “Recycled”. This question could be improved by

removing these answer options and possibly adding

in an option which would successfully attract

respondents who are unsure about the correct

answer.

6 CONCLUSIONS

A person’s level of knowledge on an ocean related

topic, and their attitude and behaviour towards that

topic are important dimensions to measure and can

be used to measure the effectiveness of ocean

literacy and general ocean environmental awareness

related tools and initiatives. An effective approach to

measuring these dimensions involves asking people

to respond to questionnaires or surveys on topics

related to the ocean. There were 3 surveys created in

this research which measure respondent’s

knowledge, attitude, and behaviour related to the

topics of micro-plastics, coastal tourism, and

sustainable fisheries. The data from responses to the

surveys was used to measure the level of knowledge,

attitude, and behaviour possessed by the respondents

in relation to the topics and it was also used to

indicate how the contents of the surveys might be

improved. In this research, the level of knowledge

possessed by the students on micro-plastics, coastal

tourism, and sustainable fisheries was found to be

slightly below medium. A statistically significant

correlation was found between attitude and

behaviour for the 3 topics, but no significant

correlation was found for the relationship between

knowledge and attitude or behaviour. The use of

Cronbach’s alpha analysis, Rasch analysis, and

distractors analysis has provided results which can

be used to improve the effectiveness of the questions

contained in the surveys. This research has

highlighted the difficulty in creating reliable and

consistent survey instruments for relatively narrow

topics.

In future research, it would be useful to apply the

results of the data analysis to a review of the

contents of the surveys with a view to improving the

questions, so that the knowledge which correlates

with a pro-ocean-environmental attitude and

behaviour can be identified. The improved questions

Measuring Individuals’ Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour on Specific Ocean Related Topics

331

could then be used as a scale to measure the

respondent’s levels of knowledge, attitude, and

behaviour in relation to the topics. The contents of

the surveys could be used to inform the measurable

objectives of the Theory of Change framework

(ToC, 2019). The information required by a

respondent to answer the questions on the

knowledge scale could then be incorporated into the

existing tools created as part of the ResponSEAble

project. Structural Equation Modelling and

Confirmatory Factor Analysis could be used as part

of the process of improving the survey questions by

creating a model of which types of knowledge

related to a topic are factors in the level of pro-

ocean-environmental attitude and behaviour

possessed by respondents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr

Matthew Ashley (University of Plymouth, UK) and

Ms Eleonora Panto (CSP, Italy) in relation to the

content of the surveys.

REFERENCES

Bitly. 2018. Bitly link management system [Online].

Available: https://bitly.com/ [Accessed November 7th

2018].

Bond, T. G. & Fox, C. M. 2007. Applying the Rasch

model: fundamental measurement in the human

sciences, Mahwah, N.J., Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Coastal Tourism. 2018. Coastal tourism key story

[Online]. Available: https://www.responseable.eu/key-

stories/coastal_tourism [Accessed December 12th

2018].

ELL. 2007. Environmental Literacy Ladder [Online].

http://www.fundee.org/facts/envlit/whatisenvlit.htm.

[Accessed February 14th 2018].

Fauville, G., Strang, C., Cannady, M. A. & Chen, Y. F.

2018. Development of the International Ocean

Literacy Survey: measuring knowledge across the

world. Environmental Education Research, 1-26.

Girard, N., Lester, S., Paton-Young, A. and Saner, M.,

2016. Microbeads:“Tip of the Toxic Plastic-berg”?

Regulation, Alternatives, and Future Implications.

Institute for Science, Society and Policy: Ottawa, ON,

Canada, pp.210-230.

Google Forms. 2018. Create online forms with Google

[Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/forms/

about/ [Accessed November 2nd 2018].

Greely, T. 2008. Ocean Literacy and Reasoning About

Ocean Issues: The Influence of Content, Experience

and Morality. University of South Florida.

Michalos, A. C., Kahlke, P. M., Rempel, K., Lounatvuori,

A., MacDiarmid, A., Creech, H. & Buckler, C. 2017.

Progress in measuring knowledge, attitudes and

behaviours concerning sustainable development

among tenth grade students in Manitoba. In

Development of Quality of Life Theory and Its

Instruments. Springer, Cham.

Micro-Plastics. 2018. Micro-plastics and cosmetics key

story [Online]. Available: https://www.responseable.

eu/key-stories/microplastics-cosmetics [Accessed

December 12th 2018].

Microbead Ban. 2018. Australian government expects

voluntary microbead ban to meet deadline [Online].

Available: https://chemicalwatch.com/63983/

australian-government-expects-voluntary-microbead-

ban-to-meet-deadline [Accessed March 22nd 2019].

Ocean Plastic. 2017. Man-made fibres and plastic found in

the deepest living organisms [Online]. Available:

https://www.ncl.ac.uk/press/articles/archive/2017/11/p

lasticocean/ [Accessed March 1st 2019].

Outfit. 2018. What do Infit and Outfit, Mean-square and

Standardized mean? [Online]. Available: https://www.

rasch.org/rmt/rmt162f.htm [Accessed October 3rd

2018].

ResponSEAble. 2015. ResponSEAble project [Online].

Available: https://www.responseable.eu/ [Accessed

March 6th 2018].

Sustainable Fisheries. 2018. Sustainable fisheries key

story [Online]. Available: https://www.responseable.

eu/key-stories/sustainable-fisheries [Accessed

December 12th 2018].

ToC. 2019. Theory of change for community-based

conservation [Online]. Available: https://www.

rare.org/sites/default/files/ToC_Booklet_Final_Rare.p

df [Accessed February 15th 2019].

Trienekens, J. H., Wognum, P. M., Beulens, A. J. M. &

Van Der Vorst, J. 2012. Transparency in complex

dynamic food supply chains. Advanced engineering

informatics, 26, 55-65.

Umuhire, M. L. & Fang, Q. 2016. Method and application

of ocean environmental awareness measurement:

Lessons learnt from university students of China.

Marine Pollution Bulletin, 102, 289-294.

Xanthos, D. & Walker, T. R. 2017. International policies

to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use

plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review.

Marine pollution bulletin, 118, 17-26.

Yoon Fah, L. & Sirisena, A. 2014. Relationships between

the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour dimensions of

environmental literacy: a structural equation modeling

approach using smartpls. Journal for Educational

Thinkers, 5, 119-144.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

332