Testing the Role of Fish Consumption Intention as Mediator

Junaidi

1

, Desi Ilona

2

, Zaitul

3

, and Harfiandri Damanhuri

1

1

Faculty of Fisheries and Marine, Universitas Bung Hatta, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Economic, Universitas Putra Indonesia YPTK, Padang, Indonesia

3

Faculty of Economic, Universitas Bung Hatta, Indonesia

Keywords:

Theory Of Plan Behaviour, Consumption Behaviour.

Abstract:

This research investigate the role of an intention to consume fish as mediating variables between six variables

(three variables from theory of plan behaviour and others from (Tomic, Matulic, and Jelic 2016). Theory of

plan behaviour is applied to understand the phenomena’s. The data is analysed using the structural equation

model (SEM). The finding show that an intention to consume fish is succeeding in mediating relationship

between attitude toward fish consumption and consumption behaviour. However, the effect of other variables

(subjective norm, perceived behavioural control, healthy, availability and responsibility) on consumption

behaviour is not successfully mediated by an intention to consume fish. This study has theoretical and practical

implication and they are discussed in this paper.

1 BACKGROUND OF STUDY

Consumption of sea food has been varying

substantialyacross countries, family and individually

(Olsen 2004).In country level, European country

consume fish 20 kg per capita and 39 kg in

Indonesia (Tran et al. 2017). In addition, Olsen

(2003) identified the stream of research regarding

to the individual fish consumption behaviour:

socio-economics and demographic perspectives,

and psychologicalperspective. From psychological

perspective, food consumption behaviour and choice

is explained by psychological constructs, such as

social norm, belief, attitude, motivation, knowledge

and other psychological variables (Shepherd and

Raats 1996). Fish consumption has several reasons,

such as diet, nutrition, and etc.(Carlucci et al., 2015).

In fact, fresh fish consumption at least twice a week

have a positively effect on health (Sioen et al.,

2008). The research question regarding to the fish

consumption behaviour is why the fish consumption

behaviour varies.

There are several previous researches

investigating the fish consumption behaviour among

individual (Tomi

´

c et al., 2016; Badr et al., 2015;

Thorsdottir et al., 2012; Murray et al., 2017; Khan

et al., 2018; Birch and Lawley, 2012; Milo

ˇ

sevi

´

c et al.,

2012; Cardoso et al., 2013; Grieger et al., 2012).

From the previous studies, there is a lack of studies

investigating the fish consumption behaviour using

the Indonesia’s data. further, there is limited studies

determining the role of an intention to consume fish

as mediating variable between attitude, subjective

norm, perceived behavioural control (Ajzen, 1991)

and other variables are being tested by (Tomic,

Matulic, and Jelic 2016): healthy, availability and

responsibility. Therefore, this study investigates

the mediating role of an intention to consume fish

between six variables and consumption behaviour.

Therefore, we test six hypotheses:

H1: Intention to consume fish mediate the

relationship between attitude and fish

consumption behaviour

H2: Intention to consume fish mediate the

relationship between subjective norm and

fish consumption behaviour

H3: Intention to consume fish mediate the

relationship between perceived behaviour

control and fish consumption behaviour

H4: Intention to consume fish mediate the

relationship between healthy and fish

consumption behaviour

H5: Intention to consume fish mediate the

relationship between availability and fish

consumption behaviour

H6: Intention to consume fish mediate the

90

Junaidi, ., Ilona, D., Zaitul, . and Damanhuri, H.

Testing the Role of Fish Consumption Intention as Mediator.

DOI: 10.5220/0009120600900097

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Science, Engineering and Technology (ICoSET 2019), pages 90-97

ISBN: 978-989-758-463-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

relationship between responsibility and fish

consumption behaviour

This paper is organised into four sessions. First

session is discussed about the research background.

Method and material is in second session. It is

followed finding and discussion as third session.

Finally, this paper is closed by conclusion and

recommendations.

2 METHOD AND MATERIAL

Academics staffs working in private university in

Padang is research object. There are 301 questioners

distributed to respondent, 18.27% of respondents

returned the questioner. Primary data is applied

by using survey method (on-line). There are

three type of latent variables used here: latent

dependent variable (fish consumption behaviour),

latent independent variables (attitude toward

fish consumption, availability, fish consumption

behaviour, healthy, perceived behavioural control,

responsibility, and subjective norm), and latent

mediating variable (intention to consume fish).

Fish consumption behaviour refers to how often

respondent consume fish the last few month (Tomic,

Matulic, and Jelic 2016). In addition, intention to

consume fish has two items adopted from (Ajzen

1991). Further, attitude toward fish consumption is

measured by five items where two items adopted

from (Tomic, Matulic, and Jelic 2016) and other three

items was taken from (Verbeke and Vackier 2005).

Thus, subjective norm has four items suggested by

(Verbeke and Vackier 2005). Moreover, perceived

behaviour control is measured by three items taken

from (Verbeke and Vackier 2005).

Healthy (involvement in health) has three items

taken from (Altintzoglou et al., 2011). Fish

availability is measured by three items from (Myrland

et al., 2000). Finally, three item is used to measure the

responsibility (moral obligation) taken from (Verbeke

and Vackier, 2005). All constructs are assessed

using the 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree,

5=strongly agree). SEM-PLS is applied to analyse the

research data (Chin 1998; Vinzi et al. 2010). In this

case, smart-pls is used (Hair et al., ). Two assessment

is conducted to gain the confirmed measurement

model and rigorous structural model (J. Hair et al.

2014). In measurement model, we have to assess two

types of validity: convergent validity and discriminant

validity (J. F. Hair et al. 2013). Structural model is

aimed for test the relationship (Joseph F Hair et al.

2017). Mediation role is tested using (Zhao et al.,

2010)’s mechanism.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Demographic Data

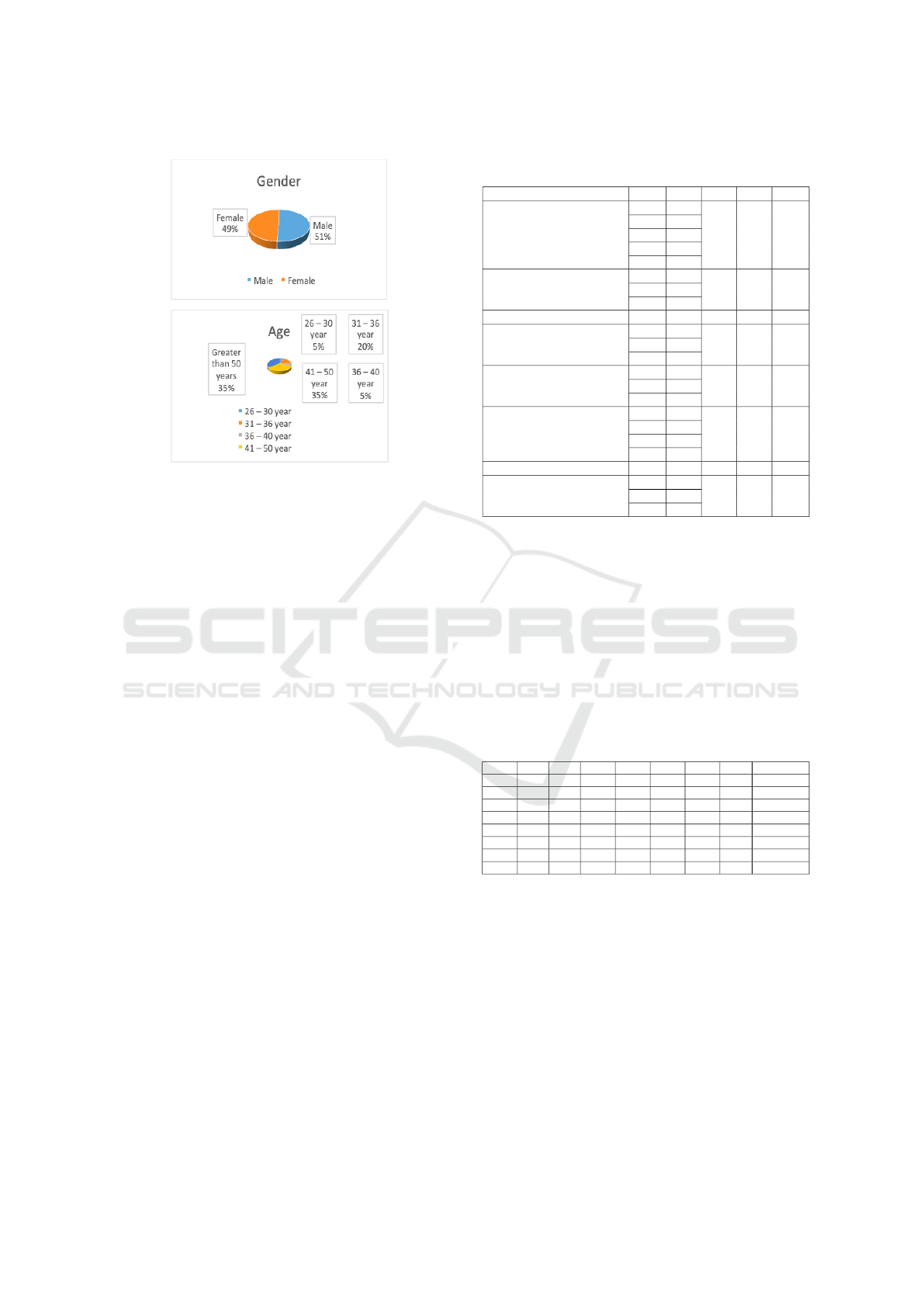

Data demography is classified into four types:

gender, age, position and income. figure 1 show

respondentgender and age. Regarding to respondent

age, 49% of respondent is female and the rest is

male (51%). In addition, respondent with age of

26-30-year-old is about 5%. Thus, 20% of respondent

is with age of 36-40 years old. Further, respondent

with age of 36-40 years old is 5% and followed

by 35% of respondent with age of 41-50 years

old. Moreover, respondent with age more than 50

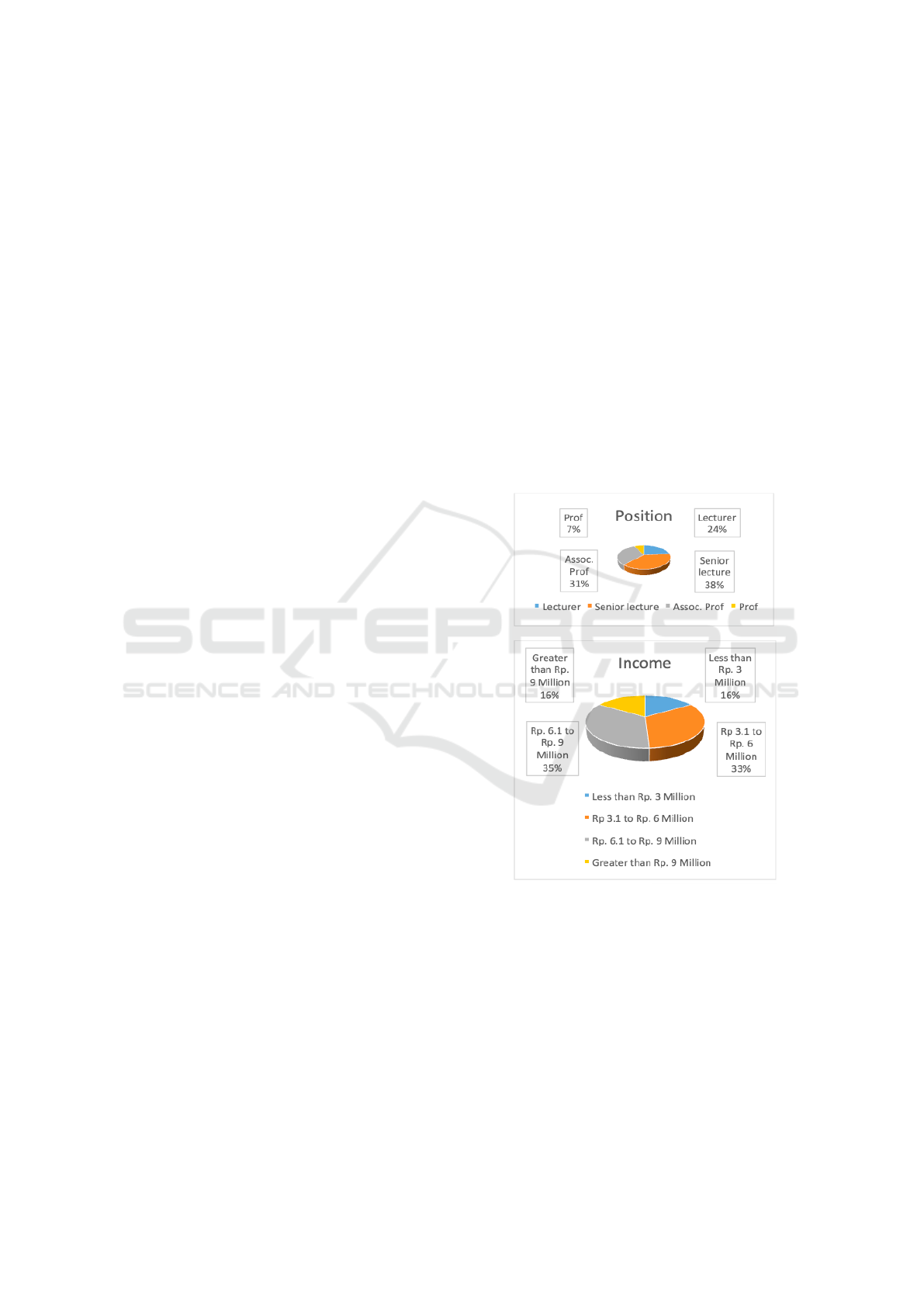

years old is 35%. On other two demographic data

Figure 1: Demographic data: gender and Age

is respondent career position and income. Figure

2 provide us with the percentage of position and

income of respondents. There are four type of lecture

position: lecturer (24%), senior lecturer (38%),

associate professor (31%) and professor(7%). In

addition, respondent with income of less than Rp. 3

million is 16% and followed by 33% respondent with

income of Rp. 3.1- Rp. 6 million. Thus, respondent

with Rp. 6.1 –Rp. 9 million of income is 35% and

finally 16% respondent is with income of more than

Rp. 6 million.

Testing the Role of Fish Consumption Intention as Mediator

91

Figure 2: Demographic Data: Position And Income

3.2 Measurement Model Assessment

as mention in the previous session, there

are two assessments while using smart-pls:

measurement model assessment and structural

model assessment(Joseph F Hair et al. 2017).

Table 1 demonstrate the result of measurement

model assessment for convergent validity. There are

four smart-pls properties used here: outer loading,

Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and average

variance extracted (AVE). All items have an outer

loading greater than 0.700 for first algorism, except

for item of perceived behavioural control (pbc2, and

pbc3). Having deleted these two items, the second

algorism has been run and thereafter, all items have

an outer loading greater than 0.700. therefore, it

reached the convergentvalidity requirement (Hulland

1999). Second convergent validity assessment is

Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite reliability

(CR) and their value must exceed 0.700 (Bagozzi and

Yi, 1988). As indicated by value of CA and CR (5th

and 6th Colum), their values are above the smart-pls

requirement: above 0.70. Finally, average variance

extracted (AVE)’s value should be greater than 0.500.

the result show that all constructs have AVE’s value

above 0.500 and therefore, it can be concluded that it

achieves the cut off value.

Discriminant validity is the second assessment

for measurement model. There are three type of

assessment for discriminant validity: Fornell-Lacker

criterion (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), cross loading

(Jorg Henseler, Ringle, and Sinkovics 2009) and

Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (J

¨

org Henseler, Ringle,

and Sarstedt 2015). Table 2 demonstrate the result of

Table 1: Measurement Model Assessment Convergent

validity

construct Item OL CA CR AVE

attitude toward fish

atf1 0.94

0.94 0.96 0.81

atf2 0.91

atf3 0.83

atf4 0.93

atf5 0.9

availability

ava1 0.87

0.89 0.91 0.79

ava2 0.81

ava3 0.96

fish con beh fcb 1 1 1 1

healthy

h1 0.88

0.79 0.87 0.7

h2 0.76

h3 0.87

intention to consume fish

icf1 0.99

0.98 0.99 0.97

icf2 0.98

icf3 0.98

subjective norm

nor1 0.9

0.86 0.9 0.71

nor2 0.73

nor3 0.9

nor4 0.81

perceived behaviour control pbc1 1 1 1 1

responsibility

res1 0.95

0.94 0.96 0.9

res2 0.97

res3 0.92

discriminant validity using Fornell-Lacker criterion.

Square root AVE of a construct should be higher

than the correlation between that construct with other

construct. For example, square root AVE of ICF

(0.984) is greater than its correlation with other

construct (0.517 with ATF, 0.032 with AVA and

etc). Therefore, it can be concluded that discriminant

validity requirement using Fornell-Lacker criterion is

achieved (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Table 2: Measurement Model Assessment Discriminant

validity-Fornel-Lacker Criterion

cons ICF ATF AVA FCB H PBC RES NOR

ICF 0.98

ATF 0.52 0.9

AVA 0.03 0.12 0.88

FCB 0.43 0.72 -0.07 1

H 0.25 0.63 0.09 0.38 0.84

PBC 0.17 0 0.31 -0.05 -0.17 1

RES 0.28 0.63 0.09 0.5 0.52 -0.05 0.95

NOR 0.23 0.57 0.21 0.41 0.54 -0.13 0.76 0.84

Note: ICF (intention to consume fish), ATF (attitude toward fish

consumption), AVA (avalaibality), (FCB) fish consumption behaviour, H

(healthy), PBC (perceived behavioural control), RES (responsibility), and

NOR (subejctive norm).

Second assesment for discriminant validity is

cross loading (Wong 2013). The result of

cross-loading can be seen in Table 3 below.The

cross-loading refers to loading an indicator should

be higher to its assigned construct (Jorg Henseler,

Ringle, and Sinkovics 2009). For example, items

for ICF construct is higher loading to ICF (bold)

compared to other construct (non-bold). It also

happens to other items. Therefore, the discriminant

validity using cross-loading is reached.

ICoSET 2019 - The Second International Conference on Science, Engineering and Technology

92

Table 3: Measurement Model Assessment Discriminant

validity-Cross Loading

Items ICF AVA FCB H ICF PBC RES NOR

atf1 0.94 0.08 0.72 0.61 0.54 -0.03 0.54 0.5

atf2 0.91 0.02 0.7 0.52 0.49 0 0.51 0.41

atf3 0.83 0.2 0.56 0.6 0.36 0.1 0.57 0.48

atf4 0.93 0.17 0.62 0.58 0.45 0.01 0.65 0.61

atf5 0.9 0.19 0.63 0.53 0.43 -0.05 0.59 0.57

ava1 0.1 0.87 0.01 0.16 0.02 0.2 0.11 0.21

ava2 0.17 0.82 -0.02 0.21 0.01 0.32 0.17 0.23

ava3 0.11 0.96 -0.1 0.03 0.04 0.33 0.06 0.19

fcb 0.72 -0.07 1 0.38 0.43 -0.05 0.5 0.41

h1 0.56 0.1 0.3 0.88 0.23 0.02 0.52 0.45

h2 0.41 -0.07 0.29 0.76 0.18 -0.3 0.24 0.4

h3 0.58 0.16 0.38 0.87 0.23 -0.17 0.51 0.5

icf1 0.52 0.03 0.41 0.29 0.99 0.14 0.29 0.24

icf2 0.49 0.02 0.42 0.22 0.98 0.19 0.27 0.21

icf3 0.51 0.04 0.44 0.24 0.98 0.17 0.27 0.23

nor1 0.53 0.21 0.34 0.48 0.21 -0.18 0.71 0.9

nor2 0.45 0.29 0.38 0.47 0.17 -0.04 0.55 0.73

nor3 0.51 0.13 0.4 0.38 0.18 -0.16 0.72 0.9

nor4 0.41 0.1 0.28 0.51 0.2 -0.04 0.56 0.81

pbc1 0 0.31 -0.05 -0.16 0.17 1 -0.05 -0.13

res1 0.59 0.03 0.46 0.5 0.27 -0.03 0.95 0.71

res2 0.62 0.08 0.51 0.53 0.32 -0.11 0.97 0.74

res3 0.58 0.16 0.45 0.45 0.19 0.04 0.92 0.71

Note: ICF (intention to consume fish), ATF (attitude toward fish

consumption), AVA (availability), (FCB) fish consumption behaviour, H

(healthy), PBC (perceived behavioural control), RES (responsibility), and

NOR (subjective norm).

Third assessment for discriminant

validity is Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio

(HTMT). The ratio is resulted from average

heterotrait-heteromethod correlations relative to the

average monotrait-heteromethod correlation (J

¨

org

Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt 2015; Joseph F Hair

et al. 2017). (Kline 2011) argue that HTMT ratio

below 0.85 indicate that discriminant validity is

achieved. Table 4 provide us with the result of

Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio and all values are below

0.85 and it can be concluded that discriminant

validity is achieved.

Table 4: Measurement Model Assessment Discriminant

validity- Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT)

cons ICF ATF AVA FCB H PBC RES NOR

ATF

AVA 0.16

FCB 0.74 0.05

H 0.72 0.21 0.43

ICF 0.53 0.03 0.44 0.29

PBC 0.04 0.33 0.05 0.22 0.17

RES 0.67 0.14 0.52 0.58 0.28 0.06

NOR 0.64 0.27 0.45 0.65 0.25 0.13 0.84

Note: ICF (intention to consume fish), ATF (attitude toward fish

consumption), AVA (availability), (FCB) fish consumption behaviour, H

(healthy), PBC (perceived behavioural control), RES (responsibility), and

NOR (subjective norm).

3.3 Structural Model Assessment

Having assessed the measurement model, assessment

for structural model is conducted. Structural model

assessment is for hypothesis testing and deals with

relationship between latent variables(Joseph F Hair et

al. 2017). before testing for hypothesis, it first looks

for predictive relevant and predictive power of model.

Q square is used to see the predictive relevance of

model and its value should be higher than 0.000.

both endogenous constructs have Q square above

0.000. in fact, FCB and ICF have Q square 0.113 and

0.254 respectively. Therefore, they are classified as

medium predictive relevance (Jorg Henseler, Ringle,

and Sinkovics 2009). Second, R square is used to see

the predictive power of structural model. The value

of R square is 0.174 and 0.222 for FCB and ICF

respectively. Thus, predictive power is below 0.33

and it is categorised as weak predicative power (Chin

1998).

Table 5: Assessment of Structural Model

endogenous construct Q square decision R square decision

FCB 0.11 Medium 0.17 Weak

ICF 0.25 Medium 0.22 Weak

relationship Coef. t stat p value decision

ATF − > ICF 0.59 3.3 0.00*** supported

AVA − > ICF -0.09 0.52 0.6 not supported

H − > ICF -0.05 0.36 0.722 not supported

ICF − > FCB 0.43 3.44 0.00*** supported

PBC − > ICF 0.19 1.38 0.17 not supported

RES − > ICF -0.04 0.26 0.8 not supported

NOR − > ICF 0 0.01 0.99 not supported

Note: ICF (intention to consume fish), ATF (attitude toward fish

consumption), AVA (availability), (FCB) fish consumption behaviour, H

(healthy), PBC (perceived behavioural control), RES (responsibility), and

NOR (subjective norm).

the significant determinants of fish consumption

intention are attitude toward fish consumption

(β=0.587, p-value=0.001). other variables (AVA, H,

PBC, RES, and NOR) do not have a significant effect

on fish consumption intention due to their p value

above 0.05. In addition, fish consumption intention

has a significant relationship with fish consumption

behaviour (β=0.434, p-value=0.001). therefore, the

higher the fish consumption intention, the greater fish

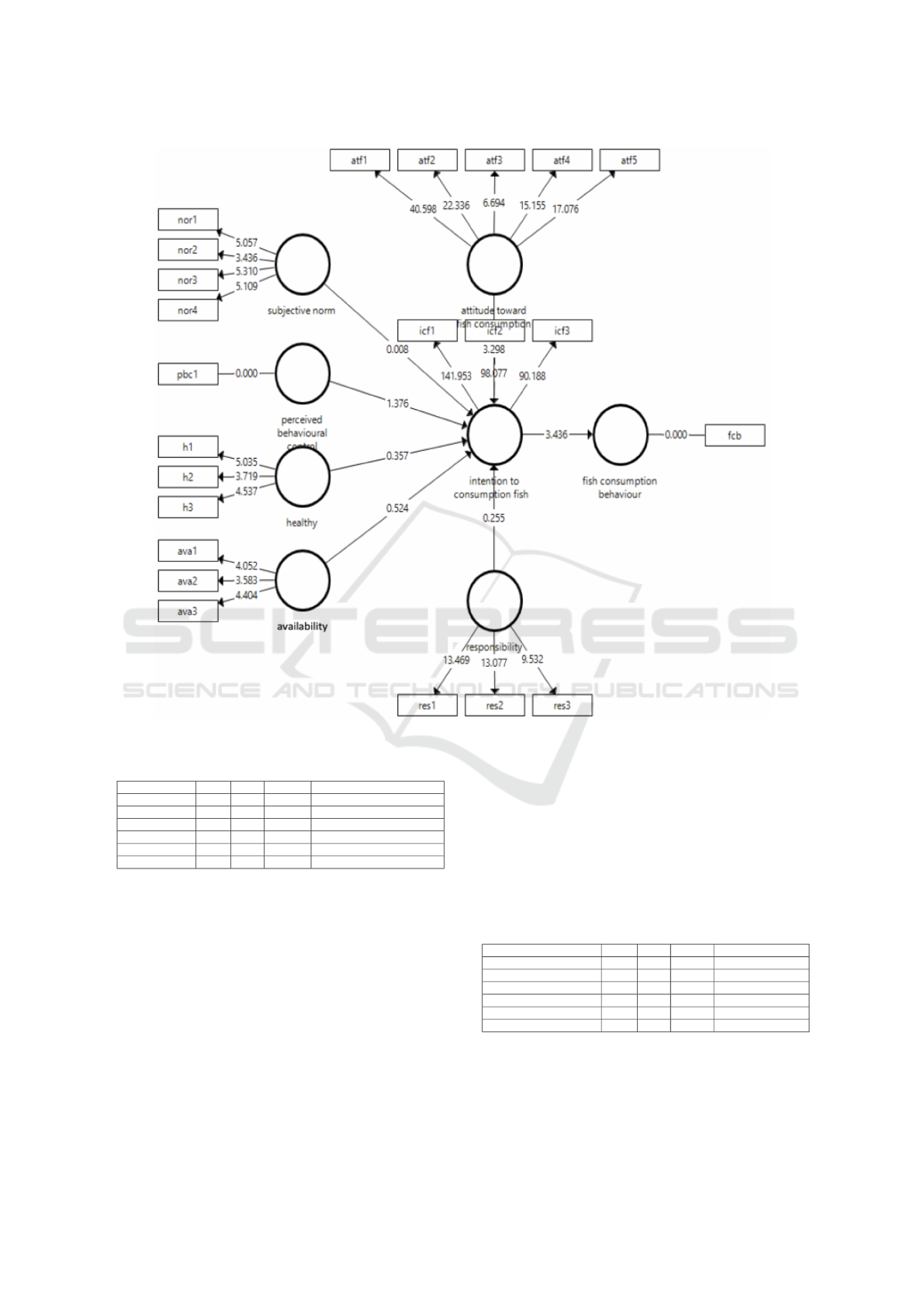

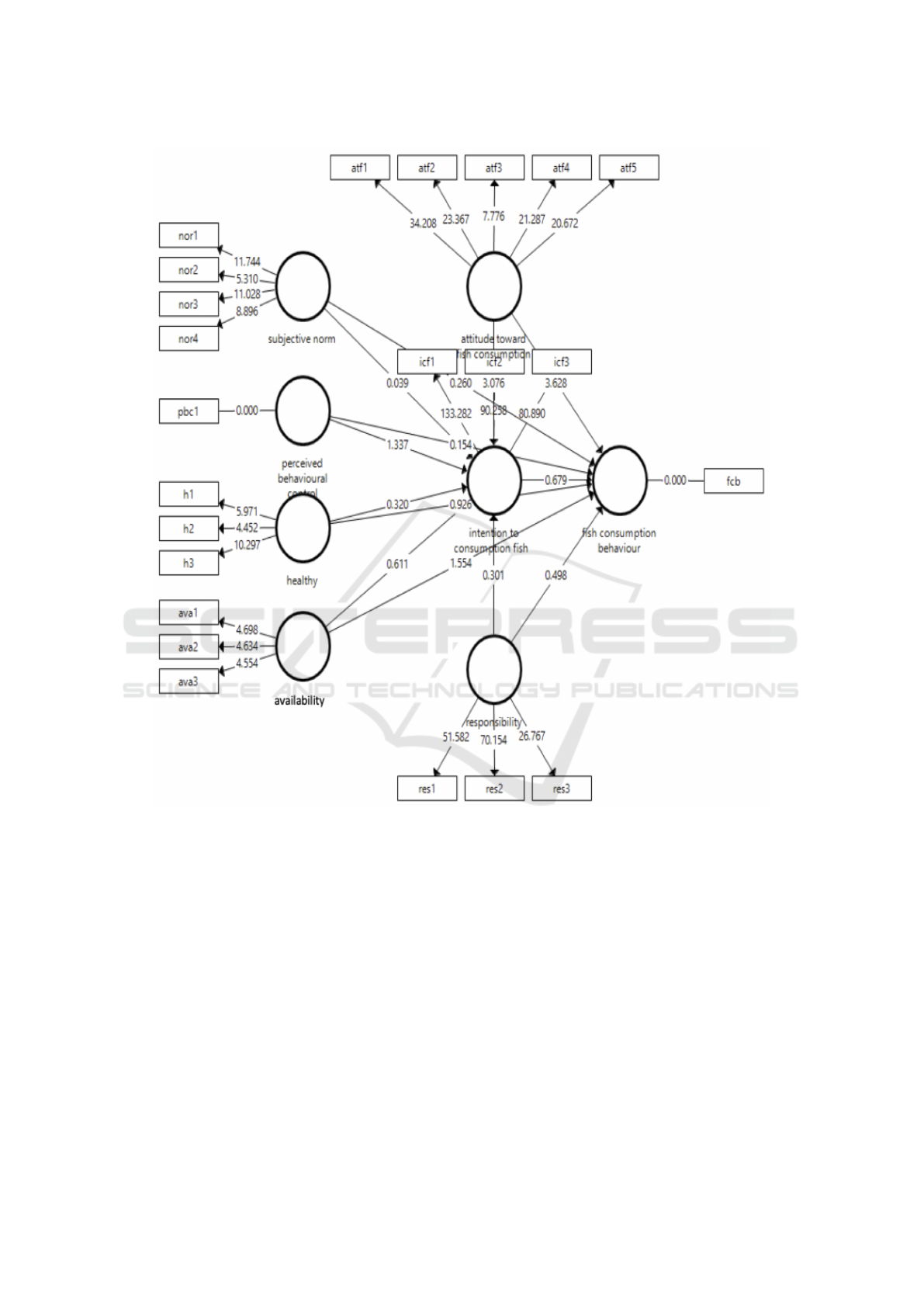

consumption behaviour. Figure 4 show the structural

model.

To answer whether fish consumption intention

mediating relationship between determinants and fish

consumption behaviour, the assessment of direct

effect and indirect effect are conducted. Table 6

demonstrate the result of direct effect and out of six

determinants, only attitude toward fish consumption

has a significant relationship with fish consumption

behaviour (β=0.702, p-value=0.000). thus, it means

that the higher the attitude toward fish consumption,

the higher fish consumption behaviour. Other

variables do not have a significant effect due to their

p value above 0.05.

Next analysis is indirect effect assessment. There

are six indirect effect are assessed and only indirect

effect (ATF− >ICF− >FCB) has a positive effect

Testing the Role of Fish Consumption Intention as Mediator

93

Figure 3: Structure Model

Table 6: Assessment of direct effect

direct effect coef. t stat p value decision

ATF − > FCB 0.7 3.63 0.00*** supported

AVA − > FCB -0.19 1.55 0.12 not supported

H − > FCB -0.13 0.93 0.36 not supported

PBC − > FCB -0.02 0.15 0.88 not supported

RES − > FCB 0.09 0.5 0.62 not supported

NOR − > FCB 0.04 0.26 0.8 not supported

Note: ICF (intention to consume fish), ATF (attitude toward fish

consumption), AVA (availability), (FCB) fish consumption behaviour, H

(healthy), PBC (perceived behavioural control), RES (responsibility), and

NOR (subjective norm).

(β=0.255, p-value=0.058) at α=10% (see table 7).

Other variables have p value above 0.05. (Zhao,

Lynch, and Chen 2010) argue that there should be

only one requirement to establish (i.e. indirect effect

(axb) is significant) and it does not need for significant

effect to be mediated (path c). However, if its

indirect effect and direct effect are significant and

they have same direction, the mediation is fallen into

complementary mediation(Zhao, Lynch, and Chen

2010). In this case, direct and indirect effect are

significant and they have the same direction (positive)

and we can conclude that there is a complementary

mediation role of fish consumption intention (ICF)

between attitude toward fish consumption (ATF) and

fish consumption behaviour (FCB). Figure 4 provide

us with complex structural model of research.

Table 7: Assessment of indirect effect

indirect effect Coef. t stat p value decision

ATF − > ICF − > FCB 0.26 1.9 0.06* supported

AVA − > ICF − > FCB -0.04 0.52 0.6 not supported

H − > ICF − > FCB -0.02 0.34 0.73 not supported

PBC − > ICF − > FCB 0.08 1.49 0.3 not supported

RES − > ICF − > FCB -0.02 0.24 0.81 not supported

NOR − > ICF − > FCB 0 0.01 0.99 not supported

Note: ICF (intention to consume fish), ATF (attitude toward fish

consumption), AVA (availability), (FCB) fish consumption behaviour, H

(healthy), PBC (perceived behavioural control), RES (responsibility), and

NOR (subjective norm).

ICoSET 2019 - The Second International Conference on Science, Engineering and Technology

94

Figure 4: Structure Model

4 CONCLUSION AND

RECOMENDATION

The important of fish has been documented by several

experts. Due to benefit of fish, studies investigating

factor effected fish consumption behaviour has

been largely done. However, there is a limited

study investigating using Indonesia’s data. In

fact, there is also lack of studies determine the

role of an intention to consume as mediating

variables between antecendents of intention to

consume fish (attitude, norm, perceived behavioural

control, healthy, availability, and responsibility)

and consuming behaviour. The finding show

that intention to consume fish is succesfully

mediated the relationship between attitude toward fish

consumption and fish consumption behaviour.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Process integration has a fairly high risk and

can have an impact on objectives. Therefore, it

is necessary to mature planning and identify the

risks that may occur either during management

system process integration.The identified risks must

be managed by defining their causes and impacts.

Once known cause and impact, it can be proposed

Testing the Role of Fish Consumption Intention as Mediator

95

preventive measures to prevent occurrence and

corrective action in response if the impact occurs.

Based on this study, there are 10 highest risks in

management system process integration and 5 risks

occuring in scope component/clause.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the financial support

provided by University of Indonesia University

through the PITTA 2019 funding scheme managed

by Directorate for Research and Public Services

(DRPM) University of Indonesia.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior.

Organizational behavior and human decision

processes, 50(2):179–211.

Altintzoglou, T., Vanhonacker, F., Verbeke, W., and Luten,

J. (2011). Association of health involvement and

attitudes towards eating fish on farmed and wild

fish consumption in belgium, norway and spain.

Aquaculture International, 19(3):475–488.

Badr, L. M., Salwa, O., and Ahmed, Y. (2015). Perceived

barriers to consumption of freshwater fish in morocco.

British Food Journal, 117(1):274–285.

Bagozzi, R. P. and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of

structural equation models. Journal of the academy

of marketing science, 16(1):74–94.

Birch, D. and Lawley, M. (2012). Buying seafood:

Understanding barriers to purchase across

consumption segments. Food quality and preference,

26(1):12–21.

Cardoso, C., Lourenc¸o, H., Costa, S., Gonc¸alves, S.,

and Nunes, M. L. (2013). Survey into the

seafood consumption preferences and patterns in

the portuguese population. gender and regional

variability. Appetite, 64:20–31.

Carlucci, D., Nocella, G., De Devitiis, B., Viscecchia,

R., Bimbo, F., and Nardone, G. (2015). Consumer

purchasing behaviour towards fish and seafood

products. patterns and insights from a sample of

international studies. Appetite, 84:212–227.

Chin, W. W. et al. (1998). The partial least squares approach

to structural equation modeling. Modern methods for

business research, 295(2):295–336.

Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W. W., Henseler, J., and Wang, H.

(2010). Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts,

methods and applications. Heidelberg, Dordrecht,

London, New York: Springer.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation

models with unobservable variables and measurement

error: Algebra and statistics.

Grieger, J. A., Miller, M., and Cobiac, L. (2012).

Knowledge and barriers relating to fish consumption

in older australians. Appetite, 59(2):456–463.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., and Christian, M. Ringle. &

marko sarstedt. 2017. a primer on partial least squares

structural equation modeling (pls-sem).

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M.

(2013). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural

Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks

Sage.

Hair, J. F., J., S., M., H., L., and Kuppelwieser, G.

(2014). V. Partial least squares structural equation

modeling (PLS-SEM) , European Business Review,

26(2):106–121.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A

new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in

variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal

of the academy of marketing science, 43(1):115–135.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2009).

The use of partial least squares path modeling in

international marketing. In New challenges to

international marketing, pages 277–319. Emerald

Group Publishing Limited.

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (pls)

in strategic management research: A review of

four recent studies. Strategic management journal,

20(2):195–204.

Khan, A. Q., Aldosari, F., and Hussain, S. M. (2018).

Fish consumption behavior and fish farming attitude

in kingdom of saudi arabia (ksa). Journal of the Saudi

Society of Agricultural Sciences, 17(2):195–199.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural

equation modeling 2nd ed. New York: Guilford.

Meiselman, H. L. (1996). The contextual basis for

food acceptance, food choice and food intake: the

food, the situation and the individual. In Food

choice, acceptance and consumption, pages 239–263.

Springer.

Milo

ˇ

sevi

´

c, J.,

ˇ

Ze

ˇ

zelj, I., Gorton, M., and Barjolle, D.

(2012). Understanding the motives for food choice

in western balkan countries. Appetite, 58(1):205–214.

Moore, R. and Lopes, J. (1999). Paper templates.

In TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. SCITEPRESS.

Murray, G., Wolff, K., and Patterson, M. (2017). Why eat

fish? factors influencing seafood consumer choices

in british columbia, canada. Ocean & Coastal

Management, 144:16–22.

Myrland, Ø., Trondsen, T., Johnston, R. S., and Lund,

E. (2000). Determinants of seafood consumption in

norway: lifestyle, revealed preferences, and barriers

to consumption. Food quality and Preference,

11(3):169–188.

Olsen, S. O. (2003). Understanding the relationship

between age and seafood consumption: the mediating

role of attitude, health involvement and convenience.

Food quality and Preference, 14(3):199–209.

ICoSET 2019 - The Second International Conference on Science, Engineering and Technology

96

Olsen, S. O. (2004). Antecedents of seafood consumption

behavior: An overview. Journal of aquatic food

product technology, 13(3):79–91.

Sioen, I., Van Camp, J., Verdonck, F., Verbeke, W.,

Vanhonacker, F., Willems, J., and De Henauw,

S. (2008). Probabilistic intake assessment of

multiple compounds as a tool to quantify the

nutritional-toxicological conflict related to seafood

consumption. Chemosphere, 71(6):1056–1066.

Smith, J. (1998). The Book. The publishing company,

London, 2nd edition.

Thorsdottir, F., Sveinsdottir, K., Jonsson, F. H., Einarsdottir,

G., Thorsdottir, I., and Martinsdottir, E. (2012). A

model of fish consumption among young consumers.

Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(1):4–12.

Tomi

´

c, M., Matuli

´

c, D., and Jeli

´

c, M. (2016). What

determines fresh fish consumption in croatia?

Appetite, 106:13–22.

Tran, N., Rodriguez, U.-P., Chan, C. Y., Phillips, M. J.,

Mohan, C. V., Henriksson, P. J. G., Koeshendrajana,

S., Suri, S., and Hall, S. (2017). Indonesian

aquaculture futures: an analysis of fish supply and

demand in indonesia to 2030 and role of aquaculture

using the asiafish model. Marine Policy, 79:25–32.

Verbeke, W. and Vackier, I. (2005). Individual determinants

of fish consumption: application of the theory of

planned behaviour. Appetite, 44(1):67–82.

Wong, K. K.-K. (2013). Partial least squares structural

equation modeling (pls-sem) techniques using

smartpls. Marketing Bulletin, 24(1):1–32.

Zhao, X., Lynch Jr, J. G., and Chen, Q. (2010).

Reconsidering baron and kenny: Myths and truths

about mediation analysis. Journal of consumer

research, 37(2):197–206.

Testing the Role of Fish Consumption Intention as Mediator

97