The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on

Regulation Compared to Other Countries

Muhammad Zulhamdani, Ria Hardiyati, Indah Purwaningsih, Chichi Shintia Laksani and Yan Rianto

Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Comparative Study, Food Industry, Functional Food Policy, Food Regulation.

Abstract: The trend of the prevalence of degenerative diseases is increasing nowadays including in Indonesia. As the

level of education and the level of income of the Indonesian people grow, consumers' desire for food products

is increasingly complex. In choosing food products, people today do not only choose foods that have a

satisfying effect but are looking for products with other advantages, one of which is functional value for

health. In developing functional food products in the food industry, many aspects must be considered and

influenced for development. One of these aspects is the regulation governing the functional food. With the

existence of clarity of regulation in the registration of functional food or food with claims to be an opportunity

for the food industry in Indonesia to produce healthy food. however, many regulations governing food have

caused the growth of the food industry in Indonesia to begin to decline. This paper examines the development

of functional food based on regulation in Indonesia and compared to other countries such as Canada, India,

Thailand, and Malaysia. Regulations regarding functional food issued by Indonesia are not much different

from countries that have issued similar regulations. The food industry that will sell food products with health

or other functional claims must provide scientific evidence and clinical trials to humans. However, this is

burdensome for the food industry because clinical trials on food that are applied are almost the same as clinical

trials on medicinal products.

1 INTRODUCTION

At this time, Indonesia faces a prolonged problem

related to food that has an impact on nutrition and

health. Consumption patterns and unhealthy lifestyles

have caused malnutrition and health problems. This

is indicated by the results of basic health research in

2018 (National Institute of Health Research and

Development, 2019) which states that the trend of

non-communicable diseases in Indonesia is

increasing such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and

obesity compared to the results of health basic

research in 2013 (Figure 1). In the end, the Indonesian

people began to realize this condition, which led to a

shift in consumption patterns that began to realize the

importance of healthy living. Along with the

increasing public awareness of food, the demand for

healthy food is also increasingly shifting. Food that is

now starting to be in great demand by consumers is

functional food that is food that not only has good

nutritional composition and attractive appearance and

taste, but also has certain physiological functions for

the body, for example to lower blood pressure, reduce

cholesterol levels, reduce levels blood sugar, increase

the absorption of calcium, and others.

Figure 1: Trend of non-communicable diseases. Source:

National Institute of Health Research and Development,

2019.

In Asia, where functional foods have been

regarded as an integral part of the culture for many

years, there is a firm belief that foods and medicine

come from the same source and serve the same

purpose. However, functional foods actually have a

Zulhamdani, M., Hardiyati, R., Purwaningsih, I., Laksani, C. and Rianto, Y.

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries.

DOI: 10.5220/0009983400002964

In Proceedings of the 16th ASEAN Food Conference (16th AFC 2019) - Outlook and Opportunities of Food Technology and Culinary for Tourism Industry, pages 153-165

ISBN: 978-989-758-467-1

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

153

quite long history. In China, Japan and other Asian

countries, many types of foods have traditionally

been associated with specific health benefits

(Weststrate et.al, 2002). In Japan, research on

functional foods started in the early 1980s. In 1991, a

specific regulatory framework concerning Food for

Specific Health Use (called FOSHU) was introduced,

which made it possible to make limited health claims

after receiving approval from the Ministry of Health.

The key to success for food manufacturers is to

develop products that are accepted by consumers and

are consistent with the consumer’s understanding and

appreciation of functional foods within the existing

culture. However, scientists and regulators have only

recently begun to agree that the functionality of

functional foods should be found in whole foods

rather than in their individual components

(Verschuren, 2002). After the introduction of the

FOSHU regulation, the number of functional food

products increased, especially from 1997 to 2007,

according to consumer demand, the net sales of the

FOSHU products were the highest in 2007 at 6.2

billion dollars (110 JPY/USD) (Iwatani and

Yamamoto, 2019). In Canada there is also no

universally accepted definition of functional foods,

but 60% of the people select foods they believe are

functional. Canada also has undertaken initiatives to

establish nutrient and health claims regulations.

These claims describe the relationship between a food

component and a disease or health-related condition.

The approval of claims has been based on an

extensive review of existing scientific literature in the

form of an authoritative statement of a scientific body

(Verschuren, 2002).

Functional food manufacturers follow specific

processes to assure the creation of products with true

values. Many regulatory authorities around the world

craft strict and detailed regulations and standards to

ensure the efficiency and safety of the foods. The

regulatory bodies also may study if the products

provide true value for consumers. Regulations vary

from country to country, which makes exporting

functional foods a challenging task, especially if the

regulations are not clear, or if the products have not

been customized to suit the regulation of the

importing country (Farid et.al, 2019).

Indonesia itself has huge opportunities for the

development of the functional food industry.

Currently, there has been a great deal of attention

given to the functionality of foods that are endemic in

Indonesia. Indonesia's traditional food wealth is very

diverse and is believed to have certain health benefits,

tempeh, honey, turmeric, ginger, aromatic ginger

(kencur), Curcuma zanthorrhiza (Javanese turmeric),

Javanese tamarind juice and so forth. Several types of

Indonesian local foodstuffs whose prospects have

been assessed for functional foodstuff include uwi

(Dioscorea alata) (Hapsari, 2014), microalgae (Nur,

2014), and sweet potatoes (Ginting et al, 2011).

Javanese tradition in the development of herbal

medicine, is a traditional wealth that has the potential

to develop functional foods typical of Indonesia.

To support the development of functional food

industry in Indonesia, there are several policies that

has been issued by government. However, these

regulations have not had a significant impact on the

development of functional food products or food with

claims in Indonesia. Functional food in Indonesia is

more dominated by processed food sourced from

fibre, milk and flour. In addition, the growth of the

food and beverage industry in Indonesia in 2018 has

decreased which is only about 7.91% compared to

2017 where the growth of 9.23% (Ministry of

Industry, 2019). Therefore, this paper explains the

development of functional food in Indonesia based on

the functional food registration process in accordance

with policies issued by Indonesia compared to other

countries such as Canada, India, Thailand and

Malaysia.

2 METHOD

This paper is based on the results of a comparative

study with scientific review of the relevant literature

and regulations or policies issued by authorized

officials in their respective countries (Canada, India,

Thailand and Malaysia) related to functional food

regulation. The selection of the countries to be studied

is based on the similarities of those countries in the

regulation of functional food.

The comparative study reveals the information

about the specific regulation, year of implementation,

the regulatory agencies, the definition of functional

food, claims, and requirements and systems for

clinical trials in each country.

3 THE DEVELOPMENT OF

FUNCTIONAL FOOD

REGULATION IN INDONESIA

Regulation on functional food in Indonesia began

since Head of Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan

(the national authority on Food and Drugs in

Indonesia) has issued basic provisions on functional

food supervision No.HK.00.05.52.0685. However,

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

154

the food fortification program that was launched in

1996 to improve the nutritional status of the

community in line with functional foods which

classified as dietary foods. The most popular

constituents of functional foods, promoted by food

industries for young children, are the very long

essential polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as omega-

3 (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid)

and omega-6 fatty acids as well as calcium

(Zawistowski, 2014). Functional foods in Indonesia

can be marketed using the same regulatory system

that is applied for conventional foods, as long as this

category of foods contains.

This regulation defined a functional food as

processed food that contains one or more functional

components which, based on scientific studies, have

certain physiological functions, are proven to be

harmless and beneficial to health. On the food label,

permitted claims are nutrition content claims and

nutrition function claims, while health claims are

prohibited.

In 2011, BPOM revised the regulation about Basic

provisions on functional food supervision in 2005

with Regulation of the head of BPOM regarding

claims in labels, and processed food advertising

supervision. In this regulation, functional food

definition is still being used. It regulates about

processed food with claim. There are three claims that

approved by the government to registered functional

food. Three claims consist of nutrition claim, health

claim and glycaemic index claims. There are 2

additional claims that did not exist in the previous

regulation, which is health claims and glycaemic

index claims. In nutrition claim consist of nutrition

claim and nutrient function claims. Then, in health

claims consist of nutrition function claims, other

function claims, and disease risk reduction claim.

Based on regulation, functional food must meet

the following requirements:

a. contains types of food components in the

amount according to the limits specified as set out

in Table 1 about other functional claims and Table

2 about claims for disease risk reduction;

b. has sensory characteristics such as appearance,

colour, or texture consistency and taste acceptable

to consumers; and

c. served and consumed as food or drinks.

Function claim and disease risk reduction claim

must be based on the results of human studies that

meet applicable scientific principles (experimental

randomized controlled trials (RCT) or observational

studies if experimental studies are not possible). In

vitro and animal research can be submitted to support

the application.

In this regulation, a list of diseases that can be

prevented through the content of functional food

components has been established in it as listed in

Table 2.

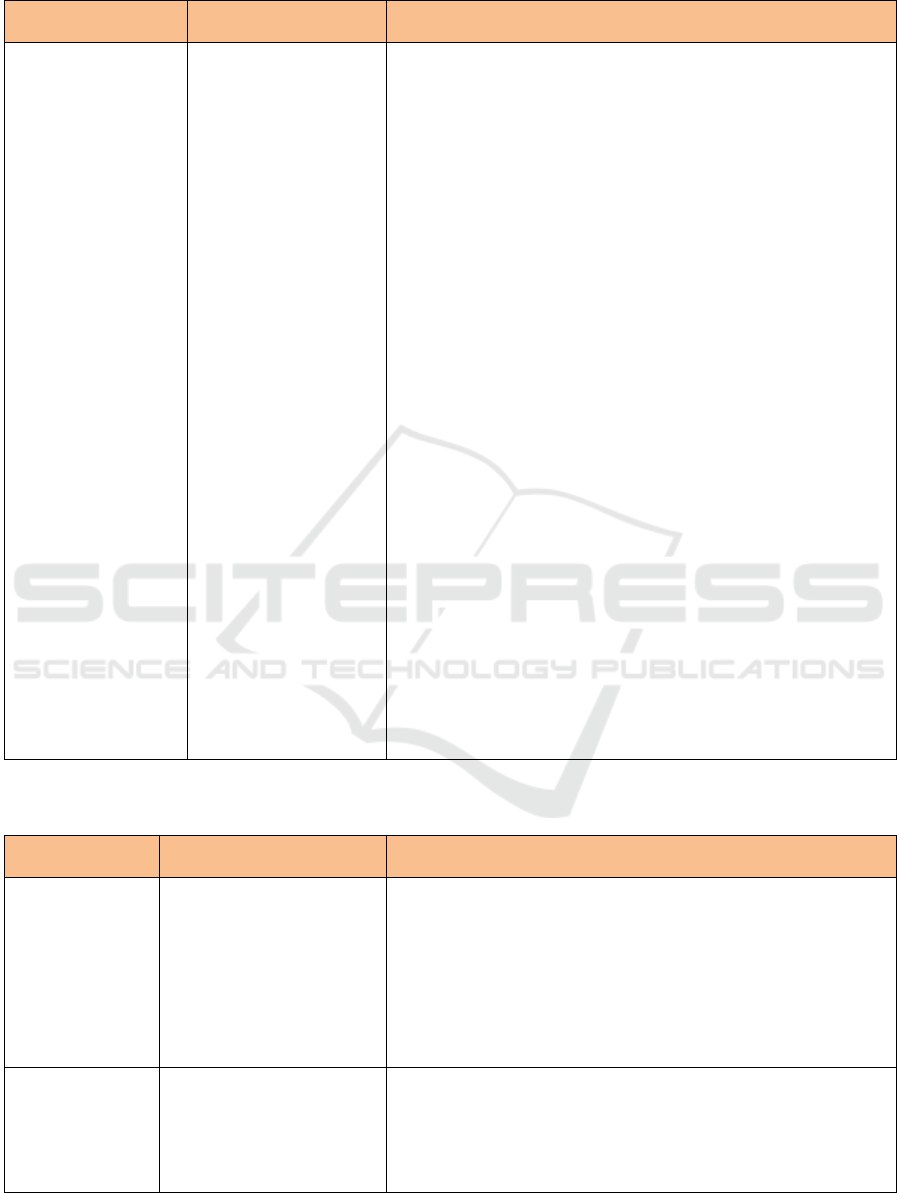

Table 1: Types of Food Component for Other Functional Claim.

Types of Food

Component

Claims

Requirements

Soluble dietary fibre

(Psyllium, beta glucan

from oats, inulin from

chicory and pectin

from fruits)

help reduce blood

cholesterol levels if

accompanied by a diet

low in saturated fat and

low in cholesterol.

a. Must include the constituent components and their sources;

b. Containing fibre at least 3 g per serving

c. total fat as much as 3 g per serving, or if the serving is less than

50 g then the total fat content is as much as 3 g per 50 g;

d. saturated fat as much as 1 g per serving and calories derived from

saturated fat as much as 15%, if the amount of serving is less than

100 grams, then the saturated fat content is as much as 1 gram per

100 grams and calories derived from saturated fat 10% maximum;

e. cholesterol as much as 20 mg per serving, or if the serving is less

than 50 g, the cholesterol content is as much as 20 mg per 50 g.

Soluble food fibre

(Psyllium, beta glucan

from oats, inulin from

chicory and pectin

from fruits)

Maintain the functioning

of the digestive tract.

a. Must include the constituent components and their sources;

b. Containing fibre at least 3 g per serving

Insoluble food fibre

Facilitate bowel

movements (laxatives)

and accompanied by

drinking enough water

a. Must include the constituent components and their sources;

b. Containing fibre at least 3 g per serving

c. Soluble fibre (beta glucan) oats of at least 3 grams or more per

day.

d. Soluble fibre from psyllium seed husk of at least 7 grams per day.

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries

155

Table 1: Types of Food Component for Other Functional Claim. (Cont.)

Types of Food

Component

Claims

Requirements

Phytosterols and

Phyto stanols

Reduce the absorption

of cholesterol from food

in the intestine if

accompanied by a diet

low in fat, low in

saturated fat, and low in

cholesterol.

• Esterifying a mixture of phytosterols from edible oil with food

grade fatty acids. A mixture of phytosterols must contain at least

80% beta-sitosterol, camp sterol and stigmasterol (combined

weight).

• Esterifying a derivative of a Phyto stanols mixture from edible oil

or a by-product of the process of making craft paper pulp with

food grade fatty acids. The phyto stanols mixture must contain at

least 80% cytostanol and campestanol (combined weight).

• at least 0.65 grams phytosterols per serving for spread and salad

dressing or;

• at least 1.7 grams phytostanols per serving for spreads, salad

dressing, snack bars, pickled milk;

• Only apply for types of food that do not require high heating in its

preparation;

• Must meet following requirements:

a. total fat as much as 3 g per serving, or if the serving is less than

50 g then the total fat content is as much as 3 g per 50 g;

b. saturated fat as much as 1 g per serving and calories derived

from saturated fat as much as 15%, if the amount of serving is

less than 100 grams, then the saturated fat content is as much as

1 gram per 100 grams and calories derived from saturated fat

10% maximum;

c. cholesterol as much as 20 mg per serving, or if the serving is

less than 50 g, the cholesterol content is as much as 20 mg per

50 g.

• For food products that contain vegetable oil, replacement of the

word "phytosterols" and " phyto stanols " to "sterol esters and

vegetable oil stanols esters" allowed the origin of the vegetable oil

is the only source of sterol ester / stanols in the food product.

• Fat content may exceed 3 g per 50 g by adding the statement: "see

nutrition information for fat content value", but still contains 0.65

g or 1.7 g phyto stanols phytosterols per 50 grams of food

especially for product spreads and salad dressings.

• Meet minimum nutrient requirements, except for salad dressing.

Source: Appendix IV in Regulation of Head BPOM, 2011.

Table 2: Types of Food Component for Disease Risk Reduction Claims.

Types of Food

Component

Claims for Disease Risk

Reduction

Requirement

Folic acid

• Reduce the risk of failure

of neural tube defects in

the fetus, with a balanced

nutritional diet.

• Reduce the risk of failure

of neural tube defects in

the fetus with

accompanied by a

balanced nutritional diet.

• Consumption of these foods a day can meet 100% RDA of folic

acid.

• The food must not contain vitamin A in the form of retinol or pro

vitamin A and vitamin D more than 100% AKG a day.

• The label should include a recommendation regarding product

preparation, which is: "The product should be dissolved in boiled

water which has a maximum temperature of 40° C, because at

high temperatures folic acid will be damaged".

Calcium

Can help slow the

occurrence of osteoporosis

in the future if accompanied

by regular physical exercise

and balanced nutritional

consumption.

• Must contain at least 75% of the RDA per day according to age

group.

• Phosphorus levels should not exceed calcium levels.

• Calcium should not be associated with height increase (bone

length).

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

156

Table 2: Types of Food Component for Disease Risk Reduction Claims. (Cont.)

Types of Food

Component

Claims for Disease Risk

Reduction

Requirement

Sugar Alcohol/

Polyol

Can help reduce the risk of

dental caries, when

associated with lifestyle

habits.

• Does not contain mono- and di-saccharides.

• Possible using the following shortened claim: "This food can help

reduce the risk of dental caries".

• Must not mention the degree of reduction in the risk of dental caries

due to consumption of food containing polyols.

• Shall not be mentioned that the consumption of food containing

polyols are the only way to reduce the risk of dental caries.

Dietary fiber

soluble (psyllium,

beta glucan from

oats, inulin from

chicory and pectin

from fruit, inulin

from chicory and

pectin from fruit)

• Can help reduce the risk

of coronary heart disease,

a disease associated with

multi factors.

• Can help control blood

sugar in patients with

diabetes mellitus type II.

• Meet the following requirements:

a. As much as 3 g total fat per serving, or if the serving is less

than 50 g, the total fat content is as much as 3 g per 50 g;

b. As much as 1 g saturated fat per serving and calories derived

from saturated fat as much as 15%, if the amount of serving is

less than 100 grams, then the saturated fat content is as much

as 1 gram per 100 grams and calories derived from saturated

fat 10% maximum;

c. as much as 20 mg cholesterol per serving, or if the serving is

less than 50 g, the cholesterol content is as much as 20 mg per

50 g.

• At least 0.6 g soluble food fibre per serving;

• Prohibited to include statements related to colon cancer.

• At least 3 g soluble fibre (beta glucan) oats or more per day.

• At least 7 g soluble fibre from psyllium seed husk per day.

Phytosterols and

phytostanols

• Can help reduce the risk

of coronary heart disease.

• Food contains phytosterols of at least 0.65 grams per serving for

spread and salad dressing or;

• Food contains phytostanols of at least 1.7 grams of phytostanols

per serving for spreads, salad dressing, snack bars, pickled milk;

• Only apply for types of food that do not require high heating in its

preparation;

• Must meet following requirements:

d. total fat as much as 3 g per serving, or if the serving is less than

50 g then the total fat content is as much as 3 g per 50 g;

e. saturated fat as much as 1 g per serving and calories derived

from saturated fat as much as 15%, if the amount of serving is

less than 100 grams, then the saturated fat content is as much as

1 gram per 100 grams and calories derived from saturated fat

10% maximum;

f. cholesterol as much as 20 mg per serving, or if the serving is

less than 50 g, the cholesterol content is as much as 20 mg per

50 g.

• For food products that contain vegetable oil, replacement of the

word "phytosterols" and " phytostanols " to "sterol esters and

vegetable oil stanols esters" allowed the origin of the vegetable oil

is the only source of sterol ester / stanols in the food product.

• Fat content may exceed 3 g per 50 g by adding the statement: "see

nutrition information for fat content value", but still contains 0.65

g or 1.7 g phyto stanols phytosterols per 50 grams of food

especially for product spreads and salad dressings.

• Meet minimum nutrient requirements, except for salad dressing.

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries

157

Table 2: Types of Food Component for Disease Risk Reduction Claims. (Cont.)

Types of Food

Component

Claims for Disease Risk

Reduction

Requirement

Peptides and

Certain Proteins

(Soybeans)

Can help reduce the risk of

coronary heart disease.

• Contains at least 6.25 g of soy protein per serving;

• Must meet the requirements:

a. as much as 120 mg sodium;

b. as much as 3 g total fat per serving, or if the serving is less than

50 g then the total fat content is as much as 3 g per 50 g;

c. as much as 1 g saturated fat per serving and calories derived

from saturated fat as much as 15%, if the amount of serving is

less than 100 grams, then the saturated fat content is as much as

1 gram per 100 grams and calories derived from saturated fat

10% maximum;

d. as much as 20 mg cholesterol per serving, or if the serving is

less than 50 g, the cholesterol content is as much as 20 mg per

50 g.

• Must specify the amount of soy protein per serving.

Soy Isoflavones

(daidzein, daidzin,

genistein,

genistin)

Can help reduce cholesterol

levels in the blood, so that it

can help reduce the risk of

atherosclerosis and coronary

heart disease".

• Must contain soy protein or peptide (as a non-isoflavone

component) and not be a pure isoflavone;

• Must contain at least 5 mg isoflavones per serving;

• Meet the following requirements:

a. as much as 3 g total fat per serving, or if the serving is less than

50 g then the total fat content is as much as 3 g per 50 g;

b. as much as 1 g saturated fat per serving and calories derived

from saturated fat as much as 15%, if the amount of serving is

less than 100 grams, then the saturated fat content is as much as

1 gram per 100 grams and calories derived from saturated fat

10% maximum;

c. as much as 20 mg cholesterol per serving, or if the serving is

less than 50 g, the cholesterol content is as much as 20 mg per

50 g.

Source: Appendix IV in Regulation of Head BPOM, 2011.

After the issuance of revised regulation in 2011,

trend of product registration on food with claim in

Indonesia was declined until 2015. In 2016, trend of

product registration was increase again as shown in

Figure 2. This indicates that the regulations issued by

the government cannot all be understood by the

applicants for registration of food products with

claims. This is caused by a change in the type of claim

that is permitted and the procedure for obtaining

approval of the claim.

In 2016, the National Agency of Drug & Food

Control (BPOM), revised the regulation. There are

some changes in the regulation of which is the

elimination of the definitions of functional foods and

its criteria. The regulation states that the definition of

functional food is replaced by food with claims.

However, this regulation increases the number of

claims in processed food.

Claim in processed food that approved by

National Agency of Drug and Food Control are

nutrition claim, health claim and other claims.

Nutritional claim consists of nutrient content claim,

and comparative nutrient claim. Health claims consist

of nutritional function claims, other functional claims,

Figure 2: Trend of Product Registration on Food with Claim

in Indonesia. Source: The National Agency of Drug & Food

Control (NADFC/BPOM), 2019.

and disease risk reduction claim. Other claims consist

of isotonic claim, no sugar addition claim, lactose

claim, and gluten claim.

Another revision that is in the new regulations is

the removal of the list of diseases (that shown in Table

2) that can be prevented through disease risk

reduction claim and replaced with legislation that any

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

158

disease risk reduction claim submission by writing to

the Head of the National Agency of Drug & Food

Control (BPOM) to do the assessment.

4 REGULATION COMPARISON

TO OTHER COUNTRIES

In this section, we explore the regulation around the

world who have similarities regulation in Indonesia.

Functional food is regulated by the rules to protect

people from consumption of wrong claimed food.

4.1 Canada

In Canada, there are no regulations dealing

specifically with nutraceuticals or functional foods.

All foods and drugs fall under the provisions of the

Food and Drugs Act and Regulations. Food is under

the governance of the Food Directorate branch of

Health Canada and all health claims applications are

assessed using the Food and Drug Regulations under

the Canada Food and Drug Act. In 1953, The

Canadian Food and Drugs Act and Regulations was

passed into law. In this regulation, definition of food

is any article manufactured, sold or represented for

use as food or drink for human beings, chewing gum,

and any ingredient that may be mixed with food for

any purpose whatever. In the summer of 1996, the

Food Directorate of the Health Protection Branch of

Health Canada began deliberations, resulting in a

policy options paper and in which the proposed

definition for a nutraceutical was a product that has

been isolated or purified from foods and is generally

sold in medicinal forms not usually associated with

food (Fitzpatrick, 2004). This institution helps people

make informed decisions about food choices

provided they are truthful and not misleading. They

assess whether health claims are truthful and not

misleading by reviewing mandatory and voluntary

pre-market submissions. Depending on the novelty of

the substance that is the subject of the health claim,

the food product may also be subject to safety

assessment if it is considered a novel food.

Health Canada in 2001 created the Natural Health

Product Directorate (NHPD) to resolve the

inconsistencies in the system. The directorate

introduced a drafted regulation that addressed issues

relating to product licensing, site licensing, good

manufacturing practices, labelling and packaging,

clinical trials, and adverse reaction reporting. The

NHP regulation in Canada came into effect in 2004.

Previously, the status quo practice was that natural

health products were not defined by the Canada Food

and Drug Act (nutraceuticals were only defined)

(Malla, et.al, 2013). Since 2004, Health Canada has

authorized more than 61,000 NHPs for sale in Canada

(as of February 27, 2013) as well as 1250

manufacturing sites for these products (Harrison &

Nestmann, 2014).

NHPs are typically sold as capsules, tablets, or

liquid preparations, like pharmaceutical products.

When these ingredients are incorporated into food

products, they are generally not classified as NHPs.

But in 1998, Health Canada clearly distinguishes

between functional food and nutraceuticals.

Nutraceuticals are isolated or purified nutrients sold

in medicinal form (e.g. pill form, or more broadly, in

doses); nutraceuticals must have a health effect. A

functional food is similar in appearance to, or may be,

a conventional food; is consumed as part of a usual

diet and is demonstrated to have physiological

benefits and/or reduce the risk of chronic disease

beyond basic nutritional functions (Health Canada

1998). Functional foods are regulated not by the NHP

guidelines but rather by the Food Directorate of

Health Canada. Finally, a nutraceutical is a product

isolated or purified from foods that is generally sold

in medicinal form, not usually associated with food;

is demonstrated to have a physiological benefit or

provide protection against chronic disease (Walji &

Boon, 2008).

Canada lacks a comprehensive statutory

framework to deal with functional food claims, and

there is currently confusion between the classification

of natural health products (NHPs) and functional

foods. NHPs and foods are both regulated under the

Canadian Food and Drugs Act (Act), in accordance

with the applicable provisions of the Food and Drug

Regulations or the Natural Health Product

Regulations (NHP Regulations). A product may be

classified as both a food and an NHP, in which case,

the product is subject to the NHP Regulations, but is

exempt from the provisions of the Act and the Food

and Drug Regulations as they specifically relate to

food. A guidance document, “Classification of

Products at the Food-Natural Health Product

Interface” was released in 2009 to assist in

determining whether products that share

characteristics of both foods and natural health

products would be classified as food or NHPs food

products that are not NHPs must comply with all the

quality and safety requirements of the Food and Drug

Regulations. Functional food claims can be broadly

grouped into three main categories: nutritional

claims, general health claims and risk-reduction

claims. The labelling restrictions and requirements

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries

159

for functional foods depend primarily on the type of

functional claim that is being asserted. (McMahon &

Reguly, 2010).

There are two types of food health claims, namely

disease risk reduction claims and function claims. A

disease risk reduction claim is a statement that links a

food or constituent of a food to reducing the risk of

developing a diet-related disease or condition. A

function claim is a statement about the specific

beneficial effects that the consumption of a food or

food constituent has on normal functions or biological

activities of the body. (Health Canada, 2019). Health

claims and nutrient content claims are permitted

under the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR) Act. A

health claim is any claim that relates the consumption

of a food or ingredient and health. Disease risk

reduction claims relate the consumption of food (or a

food component) and the risk of developing a diet-

related disease. There are nine disease risk reduction

claims currently permitted in Canada (Malla et.al,

2013).

1. Low sodium and high potassium and reduced risk

of high blood pressure,

2. Adequate Vitamin D and calcium intake and

reduced risk of osteoporosis,

3. A diet low in saturated and trans fatty acids and

reduced risk of heart disease,

4. Consumption of fruit and vegetables and reduced

risk of some kinds of cancer,

5. Maximal fermentable carbohydrates in gum and

reduced risk of dental caries or cavities,

6. Phytosterols and lowering of cholesterol,

7. Oat fibre and reduced risk of heart disease,

8. Barley products and blood cholesterol lowering,

9. Unsaturated fat and blood cholesterol lowering.

Disease risk reduction claims must not be

misleading. As such, they must be based on adequate

scientific evidence and it should be reasonable and

feasible for an individual to consume an effective

amount of the food in the context of a healthy diet.

Except for a few exempt foods (“local,” “test

market,” or “specialty” foods), claims must appear in

both English and French. When the disease risk

reduction claim is made, the food must also declare a

Nutrition Facts table, including the amount of

nutrient, mineral, or vitamin that has the disease risk

reducing effect (Malla, et.al, 2013).

4.2 Thailand

In Thailand, food regulatory system is under the

authority of the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA), which is a sub department of the Ministry of

Public Health (MOPH). This bureau controls food

business in Thailand. And regulation for food is under

the Food Act B.E. 2522 (Ratanakorn, 2016). In

Thailand, Food innovation has the potential to grow

the Thai food industry. As increase in the population

of elderly people and lifestyle-related diseases

eventually caused the necessity for positioning the

foods not only for function as nutrition, but also for

sensory/satisfaction and health, there was increasing

interested in the functional food. From literatures and

documents found that Thai functional foods are

categorized as group of foods for special dietary uses

and fortified food with health claims. Rules and

regulations governing the labelling of functional food

products is an important to commercialization of

functional foods in Thailand too. Thailand’s health

food market is 160,000 million Baht or 4.58 billion

U.S. dollars in 2014. The market growth is about 6.1

percent per year and is growing at 6.0 percent per year

until 2016. From that market, the top place at

Thailand’s health food market was functional food.

(Supachaturat, 2017).

Based on Thai Food and Drug Administration,

functional food refers to food with special dietary

uses and has a similar appearance with conventional

food. It is consumed as part of a normal diet, and

exhibit physiological benefits such as the possibility

of reducing the risk of chronic diseases (Nor et.al.,

2016). In Thailand, nutritional labelling is mandatory

only for the following categories of foods: (1) foods

with nutrition claim, comparative or nutrient function

claim, (2) foods with claims of specific benefits or

functions to the body or specific ingredients, (3) foods

for specific target groups, for instance, school

children and the elderly, (4) other foods prescribed by

the Food and Drug Administration Office. In order to

make these claims, the nutrient must be present in

food in certain quantities. Health claims are not

permitted under current food regulations; however,

the health authorities are examining the draft Codex

document on health claims and developing claims

that can be used in support of functional foods

(Zawistowski, 2014). For other claims, the FDA must

approve such claims by reviewing all supporting

evidence, including the safety data (Ratanakorn,

2016).

In 2015, the Bureau of Food, The Food and Drug

Administration of Thailand has published regulation

about Public Manual Requesting for assessment of

health claim. This regulation revised that health

claims are permitted for food label. The claimed

benefit should arise from the consumption of a

reasonable quantity of the food or food constituents

in the context of a healthy diet and shall not depend

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

160

on benefit from consumption together with other food

although it is normal practice or having intention to

consume together such as breakfast cereal is

consumed with milk. Health claims for nutrient claim

shall be based on scientific evidences to substantiate

the types of health claims as follows with systematic

review of Literature and Meta-analysis that

published in reliable journals or Recognized and

reliable technical opinions from international

recognized agencies, organizations ,or expert

committee or, and full copy of well-designed

human intervention study or other reasonable human

intervention study which number of samples and

sufficient preliminary study for consideration that

published in reliable journals as Full Text. For

diseases disk reduction, shall be has requirement

same as nutrient claims, with adding supporting

documents include peer-reviewed published articles,

animal study in vivo, ex vivo, or in vitro,

observational evidence of epidemiological study

which given its result consistent with the number of

well-designed study, evidence-based reference texts,

or other recognized and reliable texts (if any).

Adequacy of scientific evidence document depends

on quality of evidence that supported claims on

efficacy of food or constituents especially shall be

consistent with recommended use, objective of health

claims, dosage form, recommended intake duration of

intake and risk information (FDA, MPOH, 2016).

4.3 Malaysia

In Malaysia, the definition of functional foods and

nutraceuticals is still inconclusive. The term

“functional foods” is not used in the regulatory

system and there is no official definition of the term.

Food products are regulated under the Malaysian

Food Regulations 1985. A new regulation on

nutrition labelling and claims for foods was gazetted

on March 31, 2003 (Tee et.al, 2004). Nutraceuticals

and functional foods in Malaysia are distributed under

the food supplement category and not covered by the

Food and Drug Act. In trying to control the quality

and safety of these products to the consumers, the

Malaysian government under the jurisdiction of

Ministry of Health has assigned three bodies to

participate in the implementation of laws concerning

nutraceuticals and functional foods. The three

institutions consist of the National Pharmaceutical

Bureau, the Department of Food Quality, and

Malaysian National Codex Committee (Arshad,

2003).

So, there are no specific regulations for health

foods or functional foods. Currently, there are only

regulations on nutrition labelling and claims.

However, the government has appointed the Drug

Control Authority (DCA) and the National

Pharmaceutical Control Bureau to formulate a

separate regulation for dietary supplements (Lau,

2014). The Food Safety and Quality Division

(FSQD), Ministry of Health Malaysia has established

a regulatory framework to review applications for

health claims by food industry. An Expert Working

Group on Nutrition, Health Claims and

Advertisement meets regularly to evaluate

applications. Information required for applications

are clearly spell out (Tee, et.al, 2018).

In December 2010, Guide to Nutrition Labelling

and Claims for food industry has published by Expert

Committee on Nutrition, Health Claims and

Advertisement (Siong, T.E. et all, 2010). According

to Guide Book, there are several nutrition claims that

could be permitted in Malaysia as followed:

• Nutrient content claim

• Nutrient comparative claim

• Nutrient function claim and other function claim

• Claim for enrichment, fortification, or other

words of similar meaning

In Malaysia, the market for functional food is

enormous and still growing. The product considered

competitive products, whereby various products

under this category are often developed and

introduced into the market. There are three segments

in the functional food category were identified as the

main focus or strength, namely functional beverages,

dairy and soft drinks (Nor et.al., 2016). In conclusion,

regulation in Malaysia on functional food still have

restricted for claim such as claims for disease risk

reduction.

4.4 India

India has recently passed the Food Safety and

Standard Act 2006, a modern integrated food law to

serve as a single reference point in relation to

regulation of food products including nutraceutical,

dietary supplements and functional food. The Indian

Food Safety and Standard Act came into enforcement

in 2006 with two main objectives: to introduce a

single statute relating to food and to provide for

scientific development of the food processing

industry. The Food Safety and Standards Act 2006

consolidates the eight laws governing the food sector

and establishes the Food Safety and Standards

Authority (FSSA) to regulate the sector and other

allied committees. FSSA will be aided by several

scientific panels and a central advisory committee to

lay down standards for food safety. These standards

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries

161

will include specifications for ingredients,

contaminants, pesticide residue, biological hazards,

labels and others. The responsibility of framing and

regulating standards for nutraceuticals rests with the

Food Safety and Standards Authority of India

(FSSAI) as outlined in the Food Safety Act 2006.

This authority will be in charge of categories like

functional foods, nutraceuticals, dietetic products and

other similar products (Keservani, et.al, 2014).

Functional food is a relatively new concept to

Indian consumers. Food Safety and Standard Act

(FSSA) is the single reference point in relation to

regulation of functional foods in India. However,

Food Safety and Standards Authority of India

definition is relevant in Indian context. Broadly

“Functional food” may be defined as a food which

influences specific functions in the body that may

provide added health benefits or remedy from some

diseased condition following the addition/

concentration of a beneficial ingredient, or removal/

substitution of an ineffective or harmful ingredient

(Samal & Mohan, 2015). Health Claim that could be

approved by Indian Authority as followed (Sharma,

et.al, 2013, Verma & Popli, 2018):

• Nutrient function claim,

• Other function claims,

• Disease risk reduction claims.

In December 2016, Ministry of Health and Public

Welfare by the Food Safety and Standards Authority

of India has publish regulation that called the Food

Safety and Standards (Health Supplements,

Nutraceuticals, Food for Special Dietary Use, Food

for Special Medical Purpose, Functional Food and

Novel Food) Regulations. In this regulation, approval

claims are nutritional claim and health claim. The

health claim consists of two essential components,

namely nutrient or nutritional ingredients and health

related benefits. The health claim may include the

following types, but not limited to:

• Ingredient (nutrient or nutritional) function

claims,

• Enhanced function claims,

• Disease risk reduction claims,

• Health maintenance claims,

• Immunity claim – increased resistance (excluding

vaccines), and

• Anti-ageing claims.

In order to enhanced function claims and disease

risk reduction, regard shall be had to requirement of

availability of scientific literature including official

traditional texts and post market data or consumer

studies or cohort or retroactive studies based on

eating pattern and health benefits, epidemiological

international and national data, and other well

documented data, consensual, congruent and

concurrent validity studies, Health promotive and

disease risk reduction based on proof from literature

and human data of efficacy and safety of the nutrient,

not only controlled clinical trials for efficacy and

safety data, but also Nutra epidemiological data, and

qualified structure function claims for specific organ

or function which are comprehensible to consumer.

For the product led claims in respect of an article of

food based on human studies with evidence-based

data, regard shall be had to valid data and suitable

statistical design proving the benefit for disease risk

reduction, that is, human intervention studies; and

ingredient, that is, nutrient or nutritional.

For the health claim is prohibition of implied

claims for curing disease or claims of drug like

efficacy such as “Prevents bone fragility in post-

menopausal women”, and Prohibition of implied cure

for disease or claims by name of product such as

cancer cure or through pictures, vignettes or symbols,

namely, electrocardiogram tracing, lipid profile.

The FDA still allowed for industry that apply for

product with health claims without scientific support,

or if a novel ingredient is to be introduced, there shall

be a prior approval of the Authority which shall be

based on adequate scientific evidence.

4.5 Compared to Indonesian

Regulation

If compared to Indonesian Regulation, Regulation in

Canada, Thailand, Malaysia, and India has

similarities especially in approval claims. However,

Malaysia does not have permitted for health claim in

disease risk reduction. Another difference in

regulations in Indonesia compared to other countries

is the definition of functional food that has been

omitted in the latest regulations. This follows the

rules of the Codex Alimentarius which do not

regulate functional food but rather food with claims.

The latest regulations in Indonesia also state that

food with functional claims and health claims must

go through a series of experimental studies or

Random Clinical Trials. The application of RCTs is

treated the same as clinical trials on drugs. This is an

obstacle to the development of functional food

innovation, especially in clinical trials. As compared

to other countries, that to submit a health claim is

sufficient with scientific assessment evidence and in

accordance with research standards.

Table 3 shown a comparison of regulation

between Indonesia, Canada, Thailand, Malaysia and

India. From that table, Indonesia, Malaysia and India

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

162

Table 3: Comparison of regulation to other countries base on content of regulation.

Information

Indonesia

Canada

Thailand

Malaysia

India

Specific

Regulation

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Year of

Implementation

2005

1998

1998

2010

2006

Clear definition

about

functional food

Yes before

2006/ No after

2006

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Regulatory

Agencies

NADCF/BPOM

Health Canada and the

Canadian Food

Inspection Agency

(CFIA)

Food and Drug

Administration

Office

Ministry of

Health and

Expert

Committee on

Nutrition, Health

Claims and

Advertisement

the Food Safety

and Standards

Authority of

India

(FSSAI)

Nutrition

function claim

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Other function

claim

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Disease Risk

Reduction

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Clinical Trials

For disease risk

reduction claim

need Random

Clinical Trials

(RCT), and for

Probiotic need

clinical trial in

Indonesia

For disease risk

reduction, must

be based on adequate

scientific evidence and

it should be reasonable

and feasible for an

individual to consume

an effective amount of

the food in the context

of a healthy diet

Need scientific

evidence that

publish on

journal and

other evidence

like clinical

trial.

Prohibited

Health Claims

supported with

strong scientific

evidence

has established a specific regulation on claim label of

food such as nutrient claim and health claims. Canada

and Thailand regulate functional food on the Food

and Drugs regulation. That two countries do not have

specific regulation, but they have established of

functional food regulation in 1998 before Indonesia,

India and Malaysia. Each country has specific

regulatory body under Ministry of Health who

supervised functional food. Based on Approval

Claim, all countries permitted for nutrient claims and

other function claims. But in Malaysia, this country

has not allowed for disease risk reduction claims.

Based on regulation, Indonesia has implemented

specific regulations related to functional food,

although it later turned into regulation related to food

with claims. However, the growth of functional food

products in Indonesia is still not growing as shown in

figure 2. This is because functional food industries,

especially new industries, have not fully understood

the regulations regarding food with this claim which

they consider to be very complicated.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The development of functional food product in

Indonesia based on its regulation. Clarity of

regulation will be followed and obeyed by food

industry. Registration of processed food with claim

will be increase. Revised regulations regarding

claimed food specifically related to the list of

permitted claims and clarity in the procedure for

submitting food with claims, especially on claims for

disease risk reduction, will increase the number of

functional food products in Indonesia.

If we compared to other countries, Indonesia has

established the complete regulation for registration of

food with claims. The content of regulation no much

differs with Indonesia, Malaysia and India. In

Indonesia, there are nutrition function claim, other

function claim and disease risk reduction, same as

with Canada, Thailand and India. Except for

Malaysia, they do not permitted claims for disease

risk reduction.

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries

163

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support from the Ministry of

Research, Technology and Higher Education to fund

this research.

REFERENCES

Arshad, F., 2003. Functional foods from the dietetic

perspective in Malaysia. NUTRITION AND

DIETETICS, 60(2), pp.119-121.

Farid, M., Kodama, K., Arato, T., Okazaki, T., Oda, T.,

Ikeda, H. and Sengoku, S., 2019. Comparative Study of

Functional Food Regulations in Japan and Globally.

Global Journal of Health Science, 11(6).

FDA, MPOH, 2016, Public Manual of Requesting for

assessment of health claim, Thailand,

http://www.fda.moph.go.th/sites/fda_en/Shared%20D

ocuments/Manual/%E0%B8%9B%E0%B8%A3%E0

%B8%B0%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%B4

%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8

%B2%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%9B%E0%B8%A5%E0

%B8%AD%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%A0%E0%B8%B1

%E0%B8%A2/02%20PM%20Requesting%20for%20

assessment%20of%20health%20claim.pdf (August 20,

2019)

Ginting, E., Utomo, J.S., Yulifianti, R. and Jusuf, M., 2015.

Potensi ubijalar ungu sebagai pangan fungsional. Iptek

Tanaman Pangan, 6(1).

Hapsari, R.T., 2014. Prospek uwi sebagai pangan

fungsional dan bahan diversifikasi pangan. Buletin

Palawija, (27), pp.26-38.

Harrison, J.R. and Nestmann, E.R., 2014. Current Canadian

Regulatory Initiatives and Policies for Natural Health

Products (Dietary Supplements). In Nutraceutical and

Functional Food Regulations in the United States and

Around the World (pp. 183-200). Academic Press.

Health Canada. 1998. “Nutraceuticals/Functional Foods

and Health Claims on Foods.” Policy Paper

http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb

dgpsa/pdf/label-etiquet/nutrafunct_foods-nutra-

fonct_aliment-eng.pdf (July 20, 2019).

Health Canada, 2019, Health Claims,

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-

canada/services/food-nutrition/food-labelling/health-

claims.html (accessed July 20, 2019)

Iwatani, S. and Yamamoto, N., 2019. Functional food

products in Japan: A review. Food Science and Human

Wellness.

Kelley C Fitzpatrick, 2004. Regulatory issues related to

functional foods and natural health products in Canada:

possible implications for manufacturers of conjugated

linoleic acid, The American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition, Volume 79, Issue 6, June 2004, Pages

1217S–1220S, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1217S

Keservani, R.K., Sharma, A.K., Ahmad, F. and Baig, M.E.,

2014. Nutraceutical and functional food regulations in

India. In Nutraceutical and Functional Food

Regulations in the United States and Around the World

(pp. 327-342). Academic Press.

Lau, T.C., 2014. Overview of Regulations and

Development Trends of Functional Foods in Malaysia.

In Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in

the United States and Around the World (pp. 465-478).

Academic Press.

Malla, S., Hobbs, J.E. and Sogah, E.K., 2013. Functional

foods and natural health products regulations in Canada

and around the world: nutrition labels and health

claims. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada: Report

prepared for the Canadian Agricultural Innovation and

Regulation Network, pp.447-454.

McMahon, E., & Reguly, T. 2010. Canada’s approach to

functional foods. Update, 2, 26-29.

National Institute of Health Research and Development

2018. Basic Health Research (Riset Kesehatan Dasar

Riskesdas). Jakarta: Badan Penelitian dan

Pengembangan Kesehatan; 2018 (downloaded

February, 2019).

Nor, N.A.A.M., Masdek, N.R.N.M. and Sulaiman, N.H.,

2016. Functional food business potential analysis in

Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Economic and Technology Management Review,

pp.99-110.

Nur, M.M.A., 2014. Potensi Mikroalga sebagai Sumber

Pangan Fungsional di Indonesia. Eksergi, 11(2), pp.1-

6.

Ratanakorn, S., 2016. Food Regulations and Enforcement

in Thailand. Elsevier.

Shamal, S. and Mohan, B.C., 2015. Functional Food

Acceptance in India: Socio-Demographic and Lifestyle

Determinants.

Sharma, A., Kumar, P., Sharma, P. and Shrivastav, B.,

2013. A Comparative Study of Regulatory Registration

Procedure of Nutraceuticals in India, Canada and

Australia. Int J Pharm Qual Assur, 4(4), pp.61-66.

Siong, D.T.E., 2010. Guide to Nutrition Labelling and

Claims. Ministry of Health, Malaysia.

https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/file

s/MYS%202010%20Guide%20to%20Nutrition%20La

belling%20and%20Claims.pdf (July 20, 2019)

Siong, T.E., 2014. Regulatory framework of functional

foods in Southeast Asia. In Clinical Aspects of

Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals (pp. 218-237).

CRC Press.

Supachaturat, S., Pichyangkura, R., Chandrachai, A. and

Pentrakoon, D., 2017. Perspective on functional food

commercialization in Thailand. International Food

Research Journal, 24(4).

Tee, E.S., Chen, J. and Ong, C.N., 2004. Functional foods

in Asia: Current status and issues. International Life

Sciences Institute (ILSI), Southeast Asia Region.

Tee, E.S., Wong, J. and Chan, P., 2018. Functional foods

Monographs. ILSI Southeast Asia Region Monograph

Series. International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI),

Southeast Asia Region.

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

164

Verma, B. and Popli, H., 2018. Regulations of

nutraceuticals in India & US. The Pharma Innovation

Journal 2018; 7(7): 811-816.

Verschuren, P.M., 2002. Functional foods: scientific and

global perspectives. British Journal of Nutrition,

88(S2), pp. S126-S130.

Walji, Rishma and Heather Boon. 2008. “Natural Health

Products Regulations: Perceptions and Impacts.” Food

Science and Technology 19: 494-497.

Weststrate, J.A., Van Poppel, G. and Verschuren, P.M.,

2002. Functional foods, trends and future. British

Journal of Nutrition, 88(S2), pp. S233-S235.

Zawistowski, J., 2014. Regulation of functional foods in

selected Asian countries in the pacific rim. In

Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the

United States and Around the World (pp. 419-463).

Academic Press.

The Development of Functional Food in Indonesia: Based on Regulation Compared to Other Countries

165