The Effect of Self-characteristics on the Intention to Consume

Functional Foods

Sik Sumaedi, Nidya J. Astrini, Tri Rakhmawati, I Gede Mahatma Yuda Bakti and Medi Yarmen

Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Cosmopolitan, Functional Food, Innovativeness, Intention to Consume, Self-Characteristics.

Abstract: In the consumer behavior literature, self-characteristics were factors that need to be considered by companies

so they could successfully market their products. A consumer has many self-characteristics variables.

Companies must identify certain characteristics that merit their attention. This research aims to test the effect

of two self-characteristic variables; innovativeness and cosmopolitan lifestyle on the intention to consume

functional food that can prevent hypertension. The research was conducted using a quantitative research

design. The data was gathered through a survey with a questionnaire. The respondents were thirty

undergraduate students from the international class of a public university in Indonesia. The data analyses

process included validity and reliability tests and multiple regressions test. The results show that

innovativeness and cosmopolitan lifestyle did not have an impact on the intention to consume functional foods

that can prevent hypertension.

1 INTRODUCTION

Generally, the functional food market is growing

worldwide. People’s awareness of the importance of

healthy life style was a contributing factor to this

growth (Adadi et al., 2019; Siró et al., 2008). That

awareness has spurred the demand for functional food

products (Adadi et al., 2019; Siró et al., 2008).

Even though the market is growing, it does not

mean that every functional food that ever-set foot in

a market successfully accepted (Siró et al., 2008).

Siró et al. (2008) revealed that functional food

companies faced a serious dilemma. In one hand, the

development of functional foods required significant

capital. On the other hand, functional food products

did not last long in the market.

As a processed-food, a functional food product

does not only compete with other functional food

products but also with other processed foods. For

example, a functional biscuit would face competition

from other functional biscuits and traditional biscuits.

In terms of taste and price, functional foods were

having a hard time competing with conventional

foods. Therefore, the risk of failure was considerable.

According to the narration above, one of the

challenges faced by functional food companies was

ensuring that the products they developed can

compete in the market. In the marketing literature, it

is a common knowledge that when a company is

developing a product, it must also ensure that the

product would be accepted and consumed (Kotler &

Keller, 2011). In order to identify potential

consumers, a company needs to pinpoint consumers’

characteristics that match the product’s function. In

other words, the company must have a clear target, so

that its product can win the competition (Kotler &

Keller, 2011). Thus, in the context of functional food

products, a functional food company must be able to

recognize its potential consumers’ characteristics

during the product development process.

A consumer has numerous self-characteristics.

Generally, self-characteristics that are easy to identify

are the demographic profiles, like gender, locations,

marriage status, and age (Solomon, 2012). Aside

from that, a consumer also has social-psychological

characteristics, which are harder to recognize, such as

their cosmopolitanism and innovativeness (Solomon,

2012; Rogers, 1983; Vandecasteele & Geuens, 2010;

Bartles & Reinders, 2011). Functional food

companies need to identify what kind of

characteristics that need to be considered for mapping

their consumers and pinpoint the segment that most

likely would accept their product. Thus, a research

that investigates the relationship between consumers’

44

Sumaedi, S., Astrini, N., Rakhmawati, T., Bakti, I. and Yarmen, M.

The Effect of Self-characteristics on the Intention to Consume Functional Foods.

DOI: 10.5220/0009997200002964

In Proceedings of the 16th ASEAN Food Conference (16th AFC 2019) - Outlook and Opportunities of Food Technology and Culinary for Tourism Industry, pages 44-49

ISBN: 978-989-758-467-1

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

self-characteristics and their intention to consume

functional foods is important to be performed.

1.1 Previous Research and Research

Gaps

Previous studies have investigated the self-

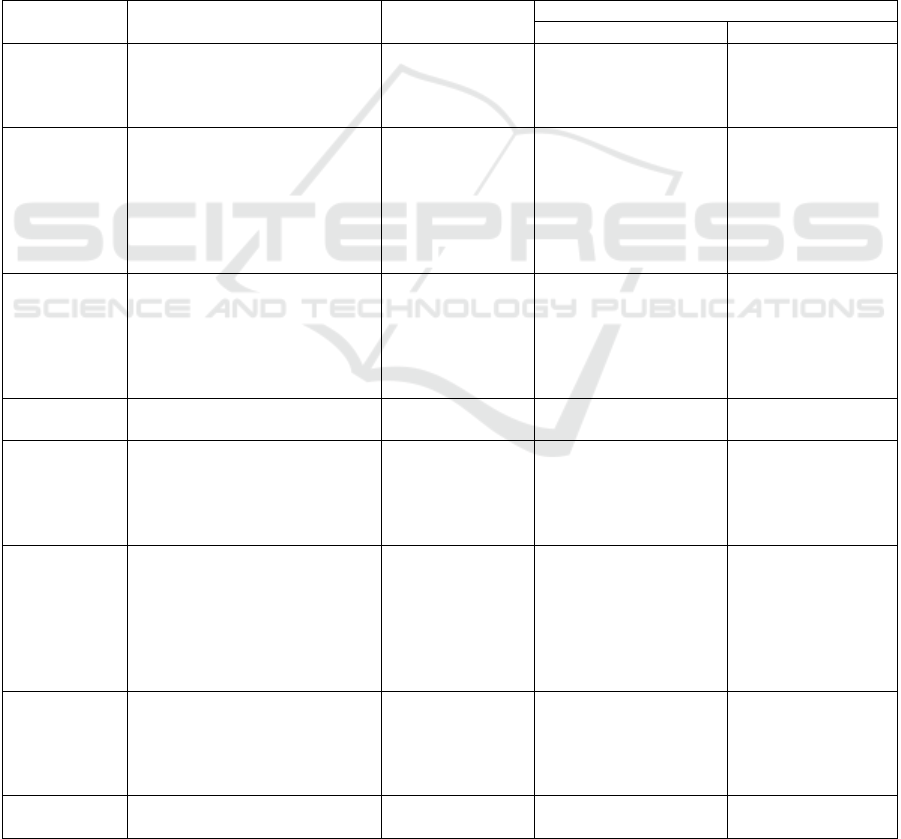

characteristics of functional food consumers. Table 1

shows some of the studies.

From the explanation above, it can be seen that the

previous studies related to self-characteristics tended

to focus on the demographic profile. On the other

hand, it is widely known that two persons with similar

demographic profiles might have different intention

to consume. For example, two 17-years old girls can

have different intention to consume food products

during lunch.

Demographic characteristics are relatively

straightforward to identify. However, socio-

psychological characteristics might create different

intention to consume between two people even when

they share the same demographic characteristics.

Functional food products can be considered as

innovative products (Bigliarda & Galati, 2013). This

condition tends to attract certain consumer types. In

the literature, consumers’ self-characteristics that

correlate with innovation are cosmopolitanism and

innovativeness. Cosmopolitanism shows to what

extent someone was exposed to

views/culture/lifestyle beyond his or her environment

Table 1: Examples of studies on the self-characteristics of functional food consumers.

Author(s) Functional food type Sample

Self-characteristics studie

d

Demo

g

ra

p

hic Socio-

p

s

y

cholo

g

ical

Chammas et al.

(2019)

Cereal bars, protein bars, protein

shakes and prebiotic yogurt

251 respondents in

Lebanon

Age, gender, educational

level, marital status,

living location, monthly

income and health status

-

Christidis et al.

(2011)

Functional food with functional

component that relates to

Calcium, fiber, vitamin D,

Omega-3 fatty acids,

Antioxidants, Whole grain

products, Phytosterols, and

Probiotics

154 respondents in

the city of

Thessaloniki

Gender, age group

(years), and education

level

Goetzke &

Spiller (2014)

Low-fat baked goods, low-sugar

baked goods, light products

(low-fat or sugar), probiotic

foods, oils with added vitamins

or omega-3 fatty acids, and sport

and fitness drinks

An online survey

of 500 German

consumers

- Wellness lifestyle

Kljusuric et al.

(

2015

)

Functional food concept

687 respondents in

Croatia

Geographical region -

Kraus (2015)

Functional food with 15

functional component

200 respondents at

the “MEDYK”

medical centers in

Rzeszow and

Lancut

- Motivation

Brečić et al.

(2014)

General functional food

424 respondents in

Croatia

Age, number of

household member,

number of children in

household, gender,

educational

achievement, and

a

g

ricultural househol

d

Perceived standard of

living, motivation

Schnettler et al.

(2015)

Functional food with 18 different

benefits

400 people in

southern Chile

The size of family,

presence and age of

children at home, ethnic

origin, education, and

socio-economic status

-

Stratton et al.

(2015)

General functional food

200 respondents in

Canada

Age, gender, education,

and income

Food neophobia

The Effect of Self-characteristics on the Intention to Consume Functional Foods

45

(Rogers, 1983), while innovativeness represents

someone’s tendency to adopt new things

(Vandecasteele & Geuens, 2010; Bartles & Reinders,

2011). Thus, cosmopolitanism and innovativeness are

predicted to have a relationship with the intention to

consume functional foods. Unfortunately, until this

time, there has not been a study that investigated

consumers’ cosmopolitanism and innovativeness in

the context of functional food.

1.2 Research Objective and Hypotheses

To fill the gaps in the literature, this study aims to:

Test the validity and reliability of the

measurement instruments for cosmopolitanism

and innovativeness in the context of functional

foods

Test the effect of cosmopolitanism on the

intention to consume functional foods

Test the effect of innovativeness on the

intention to consume functional foods

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Variables and Indicators

This research uses three main variables,

‘cosmopolitanism,’ ‘innovativeness,’ and ‘intention

to consume functional foods.’ These variables are

abstract variables, so they need to be measured using

observable variables. Abstract variables are measured

using statement indicators gathered from previous

studies to ensure their content validity (Buil et al.,

2012). Table 2 shows the operational definitions and

the leading indicators of this research.

2.2 Functional Food Type

Similar to previous studies, this research was being

limited to one type of functional food, which was

functional foods that can potentially prevent

hypertension, like yogurt, dark chocolate and low-fat

milk.

This type of food was chosen because of the rise

of hypertension in Indonesia (Ministry of Health of

the Republic of Indonesia, 2018) and this type has not

received wide coverage in the consumers’ self-

characteristics studies.

2.3 Data Collection

The data-gathering technique was a survey. This

study utilized questionnaires as instruments. The

respondents were 30 students of an international class

in a public university in Indonesia. The respondents

were recruited in a university class. To avoid bias and

gain

appropriate perception, respondents were

Table 2: Operational definitions and statement indicators.

Variable Operational

Definition

Statement indicators

Intention to

consume

functional food

The level to what

extent someone would

be willing to consume

functional foods in the

future

I plan to consume functional foods in the future (X1)

I hope I can consume functional foods (X2)

I want to try functional foods (X3)

Cosmopolitanism

To what extent

someone was exposed

to

views/culture/lifestyle

beyond his or her

environment

I enjoy sharing ideas with people from other culture or regions (X4)

I am interested to learn about people from other culture or live in other

re

g

ions

(

X5

)

I like being with people from other culture or regions to learn about their

views and a

pp

roaches

(

X6

)

I like observing people from other culture or regions to see what I can

learn from them (X7)

I like learning about other ways of life (X8)

Innovativeness

The level of self-

characteristics that

shows how eager

someone to adopt

something new

Com

p

ared to m

y

friends, I often bu

y

more new foods/bevera

g

es

(

X9

)

In m

y

circle, usuall

y

I am the first one to know about new foods

(

X10

)

In m

y

circle, usuall

y

I am the first one to bu

y

new foods/bevera

g

es

(

X11

)

When I heard about new foods/beverages, I was instantly interested (X12)

I am the type of person who’s willing to buy new foods/beverages even

thou

g

h I haven’t tried them before

(

X13

)

I am the type of person who’s buying new foods/beverages before

someone else did (X14)

Source: Adapted from Rogers (1983), Ajzen (1991), Vandecasteele & Geueens (2010), Bartles & Reinders (2011).

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

46

engaged in this study on their own volition. The

demographic profile can be seen in table 3.

This questionnaire has three parts, which are the

information related to functional foods that can

potentially prevent hypertension including product

examples, demographic profiles (see table 3), and

questions related to consumers’ assessment on

cosmopolitanism, innovativeness, and the intention to

consume functional foods (table 2). Respondents

were required to evaluate to what extent they agreed

with the statement indicators. The scale was 1 to 5.

The ‘1’ being ‘extremely disagree’ and the ‘5’ being

‘extremely agree.’

Table 3: Demographic profile.

Paramete

r

Categories %

Gender

Male 60

Female 40

Age

≤ 18

y

ears ol

d

3.4

19

y

ears ol

d

6.9

20

y

ears ol

d

62.2

≥ 21 years ol

d

27.5

Residency

status

With family (Father/Mother) 90

Dormitor

y

10

Monthly

allowance

<IDR600,001 6.9

IDR600,001-IDR1,200,000 17.2

>IDR1,200,000 75.9

2.4 Data Analysis

A two-step analysis was done. First, validity and

reliability tests of the research instrument. Factor

analysis and Cronbach’s α were employed to test the

validity and reliability. The threshold values used can

be seen in table 4. The result of the first step is used

to answer the first research question.

Table 4: Threshold values for validity and reliability test.

Parameters Criteria Threshol

d

Reliabilit

y

Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.6

Validity

Standardized factor loading

(SFL)

≥ 0.5

Source: Hair et al. (2006), Lai & Chen (2011), Sekaran & Bougie

(2010).

Second, multiple regressions analysis was

performed. The independent variables were

‘cosmopolitanism’ and ‘innovativeness,’ and the

dependent variable was ‘intention to consume

functional foods.’ The significance level used was

10%. The independent variables were deemed as

significant if it equals to or below 10%. (Hair et al.,

2006, Sekaran & Bougie, 2010).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Validity and Reliability Test

Table 5 shows the results of the validity and reliability

tests. Based on the results, this study considered that

the validity and reliability criteria had been met. The

research instrument was valid and reliable.

Table 5: The results of validity and reliability tests.

Variable Indicato

r

SFL Cronbach’s α

Intention to

consume

functional food

X1 0.878

0.762

X2 0.920

X3 0.669

Cosmopolitanism

X4 0.776

0.818

X5 0.671

X6 0.927

X7 0.831

X8 0.619

Innovativeness

X9 0.661

0.722

X10 0.703

X11 0.716

X12 0.614

X13 0.556

X14 0.674

3.2 Multiple Regressions Analysis

The result can be seen in table 6. From it, this study

concluded that cosmopolitanism and innovativeness

have a positive, but insignificant β. This shows that

cosmopolitanism and innovativeness did not have

significant impacts on the intention to consume

functional foods.

4 DISCUSSION

The first discovery of this research showed that the

research instrument used to measure

cosmopolitanism and innovativeness proposed by

this research was valid and reliable to be used in the

context of functional foods research. This finding

implicated that the instrument can be used by

functional food companies for mapping the

cosmopolitanism and the innovativeness of their

target consumers. Knowledge on this would also be

helpful for companies in developing a marketing

strategy. Aside from that, for researchers and other

academics, a valid and reliable measurement

instrument can be used to learn functional foods

phenomena related to cosmopolitanism and

innovativeness.

The Effect of Self-characteristics on the Intention to Consume Functional Foods

47

Table 6: The results of multiple regressions analysis.

Independent Variable

Regression

coefficient

Standard error of

coefficient

Standardized

regression coefficient

(

beta

)

t value

Statistical

significance

Interce

p

t -0,138 0.188 0.000 1.000

Cosmo

p

olitan -0.037 0.195 -0.037 -0.188 0.852

Innovativeness 0.095 0.195 0.095 0.490 0.628

R2 = 0.009

F value = 0.125

P level = 0.883

De

p

endent Variable : Intention to consume functional foo

d

The second finding indicated that

cosmopolitanism did not have a significant effect on

the intention to consume functional foods. This

means people with high cosmopolitanism and low

cosmopolitanism have a similar tendency to consume

(or not to consume) functional foods. The

development of functional foods products can target

consumers with both low and high cosmopolitanism.

The third finding indicated that innovativeness

did not significantly affect the intention to consume

functional foods. This means that consumers with

high and low innovativeness have a similar tendency

to consume functional foods. For companies, it

implies that consumers with both high and low

innovativeness can be targeted.

Simultaneously, the second and the third findings

signified that the market for functional foods would

grow even though the potential target market was

neither consisted of people who are easily exposed to

culture/value/experience beyond their current

environment nor people who like to try new things.

Functional food companies should not be careless in

the investment of product development by focusing

on people who tend to be exposed to new

culture/value/experience or people who like to try

new things.

Even though this study has generated interesting

findings and provided important implications, there

are still unfinished agendas. First, this research found

that cosmopolitanism and innovativeness did not

have significant impacts on the intention to consume

functional foods. However, this research has not

deeply investigated the reasons behind this

insignificancy.

Second, in addition to exploring reasons behind

that finding, this research also raised a question on the

threshold of ‘the innovativeness of functional foods,’

so it can be perceived as new. The insignificancy

might be caused by a perception that functional foods

are not new or innovative. Another question arose.

Would cosmopolitanism and innovativeness pose

significant impacts on the intention to consume if

they were applied to other types of functional food?

This study has not been able to answer this question

since it only dealt with one type of food.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is funded through Insentif Riset Sistem

Inovasi Nasional (National Innovation System

Research Incentive) The Ministry of Research and

Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia. All

authors are the main author of this paper.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, Icek, 1991. The Theory of Planned Behaviour.

Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision

Processes, 50 : 179 – 211.

Adadi, P., Barakova, N. V., Muravyov, K. Y.,

Krivoshapkina, E. F., 2019. Designing selenium

functional foods and beverages: A review. Food

Research International, 120: 708-725.

Bartels, J., Reinders, M., 2011. Consumer innovativeness

and its correlates: A propositional inventory for future

research. Journal of Business Research, 64: 601–609.

Bigliardia, B., Galati, F., 2013. Innovation trends in the

food industry: The case of functional foods. Trend in

Food Science & Technology, 31: 118-129.

Brečić, R., Gorton, M., Barjolle, D., 2014. Understanding

variations in the consumption of functional foods –

evidence from Croatia. British Food Journal, 116(4):

662-675.

Buil, I., Chernatony, L., Martinez, E., 2012.

Methodological issues in cross-cultural research: An

overview and recommendations. Journal of Targeting

Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 20(3-4):

223-234.

Chammas, R., El-Hayek, J., Fatayri, M., Makdissi, R., Bou-

Mitri, C., 2019. Consumer knowledge and attitudes

toward functional foods in Lebanon. Nutrition & Food

Science, 49(4): 762 - 776.

Christidis, N., Tsoulfa, G., Varagunam, M.

Babatzimopoulou, M., 2011. A cross sectional study of

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

48

consumer awareness of functional foods in

Thessaloniki, Greece. Nutrition & Food Science, 41(3):

165–174.

Goetzke, B. I., Spiller, A., 2014. Health-improving

lifestyles of organic and functional food consumers.

British Food Journal, 116(3): 510 – 526.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E.,

2006. Multivariate data analysis. 5

th

ed. Prentice-Hall,

New Jersey.

Kljusuric, J. M., Cacic, J, Misir, A., Cacic, D., 2015.

Geographical region as a factor influencing consumers

perception of functional food – case of Croatia. British

Food Journal, 117(3):1017-1031.

Kotler, P., Keller, K., 2011. Marketing Management.

Prentice Hall, NJ.

Kraus, A., 2015. Factors influencing the decisions to buy

and consume functional food. British Food Journal,

117(6): 1622-1636.

Lai, W., Chen, C., 2011. Behavioral intention of public

transit passenger – the role of service quality, perceived

value, satisfaction and involvement. Transport Policy,

18: 318-325.

Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia, 2018.

Hasil Utama Riskesdas. Ministry of Health Republic of

Indonesia, Jakarta.

Rogers, E. M., 1983. Diffusion of innovations. Macmillan

Publishing Co., Inc., London.

Schnettler, B., Miranda, H., Lobos, G., Sepulveda, J.,

Orellana, L., Mora, M., Grunert, K., 2015. Willingness

to purchase functional foods according to their benefits.

British Food Journal, 117(5): 1453-1473.

Sekaran, U., Bougie, R., 2010. Research Methods for

Business: A Skill Building Approach. 5

th

ed. Wiley,

Chichester.

Siró, I., Kápolna, E., Kápolna, B., Lugasi, A., 2008.

Functional food. Product development, marketing and

consumer acceptance - A review. Appetite, 51(3): 456–

467.

Solomon, M. R., 2012. Consumer Behavior: Buying,

Having and Being. Prentice Hall, London.

Stratton, L., Vella, M., Sheeshka, J., Duncan, A., 2015.

Food neophobia is related to factors associated with

functional food consumption in older adults. Food

Quality and Preference, 41: 133-140.

Vandecasteele, B., Geuens, M., 2010. Motivated Consumer

Innovativeness: Concept, measurement, and validation.

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(4):

308–318.

The Effect of Self-characteristics on the Intention to Consume Functional Foods

49