Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

Thi Thuy Phan

1,∗

, Ho-Pun Lam

2

, Mustafa Hashmi

2,3

and Yongsun Choi

4

1

CMC Ciber, Vietnam

2

Data61, CSIRO, Sydney, Australia

3

La Trobe Law School, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

4

Inje University, Gimhae, Republic of Korea

Keywords:

Korean Legislation, Legal Taxonomy, Legal Norms Classification, Semantic Types.

Abstract:

Automating information extraction from legal documents and formalising them into a machine understandable

format has long been an integral challenge to legal reasoning. Most approaches in the past consist of highly

complex solutions that use annotated syntactic structures and grammar to distil rules. The current research

trend is to utilise state-of-the-art natural language processing (NLP) approaches to automate these tasks, with

minimum human interference. In this paper, based on its functional aspects, we propose a legal taxonomy of

semantic types in Korean legislation, such as definitional provision, deeming provision, penalty, obligation,

permission, prohibition, etc. In addition to this, a NLP classifier has been developed to facilitate the automated

legal norms classification process and an overall F

1

score of 0.97 has been achieved.

1 INTRODUCTION

The legislation that we have nowadays is not simply

a corpus of legal documents. It contains lots of in-

formation that needs to be interpreted, explained, and

processed in order to determine whether an organisa-

tion complies with legislative requirements. However,

working with legal documents can be both costly,

time-consuming and error-prone, as it requires do-

main experts to understand what to be expected from

the legislations with respect to its interpretation and

intents.

Over the years, much research has been focused

on representing information captured inside legal doc-

uments into machine understandable formalisms so

that we can reason on and make sense of it using a

computer, and various promising results have been

obtained (Ceci et al., 2016; Lam and Hashmi, 2019).

Recently, the research focus has been shifted

to the task of applying natural language processing

(NLP) techniques to generate legal norms from le-

gal documents with some success (van Engers et al.,

2004; Wyner and Peters, 2011; Dragoni et al., 2015;

Sleimi et al., 2018). However, most of these ap-

proaches consist of highly complex solutions that

∗

This work was done during the time when the first

author was a Master student at Inje University, Republic of

Korea.

utilise annotated syntactic structures and grammar to

automatically distil rules. Recently, Ferraro et al.

(2019) have evaluated several state-of-the-art NLP ap-

proaches to automate the normative mining process

and have identified several issues such as different

types of lexical ambiguities, inconsistent use of termi-

nologies, sentential complexities, cross-referencing

between different provisions, etc., that hinder the de-

velopments in this area.

Nevertheless, at the core of these technologies is

an ontology that defines the underlying principles,

concepts, assumptions, and legal effects of terms, i.e.,

the legal taxonomy that are commonly used in a le-

gal domain. It classifies the terms into different cate-

gories and defines their interrelations, such as whether

a term is subsumed, equivalent, or in conflict with an-

other term. It is a foundation stone that can facilitate

the development of automated legal analysis and au-

tomatic machine translation.

The Language for Legal Discourse (LLD) (Mc-

Carty, 1989) is a first attempt to define legal knowl-

edge in the context of legal reasoning. Since then,

many different legal ontologies have been devel-

oped for a range of purposes. For instance, Legal

Knowledge Interchange Format (LKIF) Core ontol-

ogy (Hoekstra et al., 2007) provides the basic set of

concepts of law, such as the meaning of norm, lia-

bility and legal fact, etc., as the basis for knowledge

86

Phan, T., Lam, H., Hashmi, M. and Choi, Y.

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation.

DOI: 10.5220/0010122400860097

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2020) - Volume 2: KEOD, pages 86-97

ISBN: 978-989-758-474-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

acquisition and modelling in the legal domain. It aims

to limit the set of terminologies used in LKIF appli-

cations.

Several European projects such as LYNX,

1

SPIRIT,

2

and MARCELL

3

have dedicated efforts for

creating legal knowledge graphs and multilingual le-

gal ontologies for automatically linking and trans-

lating heterogeneous legal sources such as laws, de-

crees, regulations, facilitating thus enterprises to re-

move their legal and language barriers in trade and to

localise their products and services.

As can be seen above, the research efforts in this

area target mostly Indo-European languages. In South

Korea, the work related in this area is still in its incu-

bation stage. Regulation technologies (RegTech) and

their related products have started gaining attention

from the government only until 2018.

4

Several word

characters and knowledge representation (Botha and

Blunsom, 2014; Cotterell and Schütze, 2015; Wieting

et al., 2016), and NLP approaches (Bojanowski et al.

(2016); Junho et al. (2010); Stratos (2017)) in Korean

language exist, but not much useful and efficient sys-

tems have been reported.

Extracting normative information from legal doc-

uments is a process that is far from being trivial and

intuitive. Legal documents are typically so complex

that even human lawyers are having difficulties in un-

derstanding and applying them (Wieringa and Meyer,

1993). Thus, works on the automated transformation

of Korean legislations into a machine understandable

formalism are in high demand.

Hence, the purpose of this paper is to fill the gap in

this area by proposing a taxonomy of semantic types

for legal norms in the Korean language that can be

applied to statutory texts in Korean legislations. The

primary challenge to the classification of legal norms

lies in the underlying legal theory with empirical ob-

servations, which is under-represented in Korean le-

gal sciences. It is the foundation of many legal anal-

ysis and interpretation tasks, and not much work has

been reported by the Korean legal informatics com-

munity.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. An

informal introduction and problems related to the Ko-

rean language will be described in Section 2. Sec-

tions 3 and 4 present the taxonomy of legal norms that

we have developed on Korean legislation and the pre-

liminary evaluation results of the taxonomy, respec-

1

LYNX: http://lynx-project.eu/

2

SPIRIT:https://www.spirit-tools.com/

3

MARCELL: http://marcell-project.eu/

4

Fintech In South Korea: Regulators Step In To Boost

Innovation: https://fintechnews.hk/4823/fintechkorea/finte

ch-south-korea-regulators-step-boost-innovation/

tively. Section 5 presents the related works, followed

by conclusions and pointers to future research.

2 BACKGROUND

Technically, a taxonomy typically refers to a hier-

archical arrangement of terminologies that describes

a particular branch of science or field of knowl-

edge (McGregor, 2005). A legal taxonomy, in addi-

tion to this, reflects also the culture and history of a

given legal system. As commented by Mattei (1997),

it is the product of interactions of the legal tradition

and that of the new sensibilities. It provides a means

where people working in the legal sector can commu-

nicate with each other, to discuss problems and ex-

change ideas of mutual concern among themselves.

However, creating a legal taxonomy that accu-

rately reflects the legislations and to avoid misattri-

bution errors is not an easy task. It requires the terms

selected and arranged to be mutually exclusive, thus

a unique ordered structure for different terms can be

created (McGregor, 2005).

2.1 Problems with Korean Language

There are a few phenomena that make NLP in Korean

language a challenging task to accomplish.

Firstly, Korean has traditionally posed challenges

for word segmentation and morphological analy-

sis (Matteson et al., 2018). This is because Korean is

a phonetic language with a subject-object-verb (SOV)

syntax while permitting a high degree of freedom in

word order (Jeong et al., 2007). In fact, Korean is a

left-branching language such that the head that deter-

mines the correct phrasal category comes at the end of

a phrase (Müller-Gotama, 1994). For a noun phrase

that is compatible with a higher phrase type, it could

be the left-branching daughter of a higher phrase,

noun phrase, or verb phrase, which imposes substan-

tial demand for the model being developed (Müller-

Gotama, 1994).

Secondly, it also allows multiple concepts to be

synthesised into a single eojeol, i.e., a Korean spacing

unit similar to a word in English. As a result, depend-

ing on the context, the same eojeol can be analysed

into different morpheme which yields different part of

speech (POS) tags of morpheme combinations (Song

and Park, 2019).

Thirdly, Korean is an agglutinative language such

that words may contain different morphemes to deter-

mine their meanings. For example, the word “moun-

tain” in English can only be derived from itself;

whereas in Korean, “” (san-eul (mount)), “”

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

87

(san-eun (saneun)), “ ” (san-do (acidity)), “

” (san-yi (sanyi)), “” (san-ina (sanna)), etc.,

can all be derived from the root “” (san (moun-

tain)) (Lee, 2018). To make things even more com-

plex, Korean also has some special rules that can ap-

ply across character boundaries, implying that mor-

phological transformation may also occur among ad-

jacent graphemes.

Over the years, several lexical databases have

been developed. For instance, KorLex (Yoon et al.,

2009) was developed by translating and mapping the

English terms into Korean. Following the idea of lex-

ical concept network (LCN) — a lexical database that

provides various information of a word in terms of

its relation to other lexical units, Choi et al. (2004)

developed ETRI LCN for the Korean language, but

for verbs and nouns only. Later, the same group of

researchers also established (and maintained) another

LCN called UWordMap (Ock, 2013), which consists

of 514,314 words, including nouns, adjectives, and

adverbs, and is the largest lexical database of its kind.

However, all these works are for general purposes

only, they do not cater to the needs of the legal do-

main that requires a more rigid understanding of the

legal text.

2.2 Semantic Types

Generally, legal rules governing the behavior of citi-

zens prescribe code of actions that citizens must fol-

low. These codes provide applicability conditions

capturing various intuitions in different situations and

prescribe on how to act. Several research efforts have

been reported providing classifications of legal rules

defining the semantic meanings to facilitate properly

interpreting of and reasoning about the legal rules.

von Wright (1963) classifies legal rules as (i) deter-

minative rules (a.k.a. constitutive rules) which define

the concepts, or activities that cannot exist without le-

gal rules; (ii) technical rule prescribing what needs

to be done in order to attain some legal effects, and

(iii) prescriptive rules that prescribe the actions and

making obligatory, prohibited, or permitted regulat-

ing thus the behavior of the subject.

Gordon et al. (2009) give an extended catalog

of requirements for a formal language necessary for

reasoning on legal rules which includes jurisdic-

tion (Mills, 2014), authority, rules validity (Marín

and Sartor, 1999), deonticity and defeasibility of

rules, normative effects (Rubino et al., 2006), contra-

position (Prakken and Sartor, 1996), conflicting (Sar-

tor, 1992) and exclusionary rules (Sartor, 1992;

Prakken and Sartor, 1996), and temporal properties.

Hilty et al. (2005) provides a charaterisation of le-

gal norms along temporal bounds and invariants prop-

erties capturing the application of norms in the time

space. Whereas Hashmi et al. (2013) classify deon-

tic effects of legal norms on the temporal validity as-

pects (Palmirani et al., 2011). The former provides the

mapping of the norms from requirements to the en-

forcement while latter studies when a norm enters into

force, terminated after a deadline what constitutes the

violations of a legal norm, and whether a violated

norm can be compensated for. Besides, they study

the persistent effects of legal norms such that even af-

ter being violated a norm may still remain valid until

it is performed or terminated.

More recently, Hashmi et al. (2018) discuss a tax-

onomy of legal terms and concepts aiming at creat-

ing a legal ontology and a socio-legal graph for shar-

ing the Australian legal knowledge on the web. Their

taxonomy is based on the legal quadrant for rule of

law (Casanovas, 2019) comprising the notions of ap-

plication and implementation of the rule of law which

includes themes such as binding power, social dialog,

privacy, trust, security, sanctions, etc., and sources for

the legal validity (Sartor, 2008) of the legal norms

emerging from regulatory dimensions such as hard

law, soft law, policies, and ethics covering a range of

requirements from various social, political and legal

aspects.

3 THE LEGAL TAXONOMY

Failure to properly understand the real meanings of a

legal term may result in the misunderstanding of leg-

islation provisions. In practice, the way that we in-

terpret legislations may also affect the outcome of a

case.

Technically, legislation can be characterised as a

combination of a set of (normative) provisions and

the totality of norms that follow from executing that

finite set of provisions. In the past, legislations were

interpreted mainly based on the plain meanings of the

text as derived from the ordinary definitions of an in-

dividual word and the overall structure of the state-

ment (Karkkainen, 1994). Contemporary approaches

to legislation interpretations focus on determining the

original intent of the legislation, i.e., the goals that the

legislation intended to achieve. Interpretations will

be made in the context of the legislation as a whole

where the interpretation of a specific provision should

5

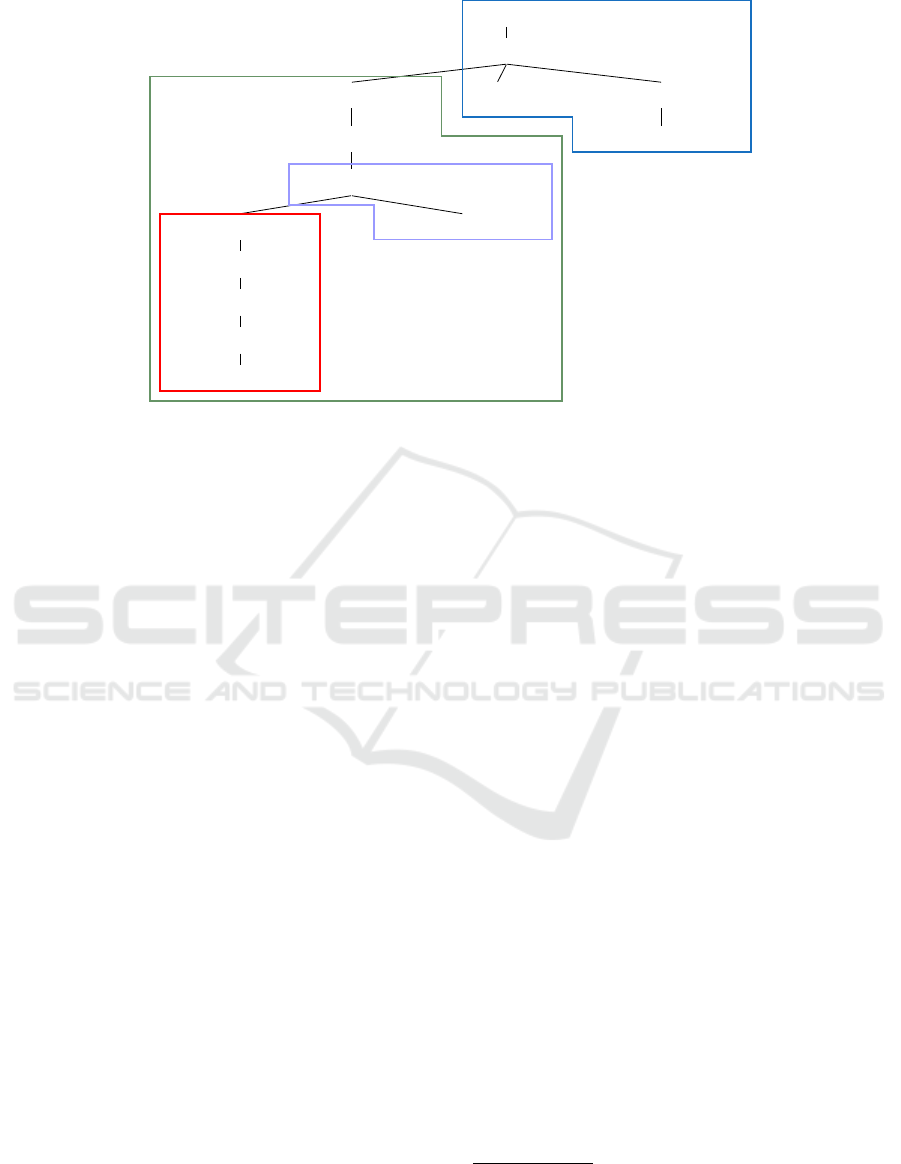

The parse tree in Figure 1 was generated using the syn-

tax tree generator, Komoran3, available at: http://andrewma

tteson.name/psg_tree.htm (last accessed: 21 Jun 2020)

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

88

/ ROOT

/ VP

/ VP

/ NP_OBJ

/ VP_MOD

/ NP_AJT

/ VP_MOD

/ NP_OBJ

/ VP_MOD

1 / NP_AJT

/ NP_AJT

/ AP / NP_OBJ

/ NP_MOD

Delegated Qualification

Legal effects

App Condition 1

App Condition 2

Figure 1: Parse tree of the statement

5

: “1

.” (statement extracted from the 2nd paragraph of Article 18 in Insurance Business

Act).

be determined consistently with respect to other pro-

visions. Hence, to meet the needs of both the le-

gal practitioners and design requirements of the au-

tomated machine translation and interpretations pro-

cess, having a clear definition of terminologies is cru-

cial to avoid any ambiguity and eliminate potential

misinterpretations in the legislations.

3.1 The Basic Concepts

In this subsection, we present a basic set of definitions

that will be used throughout the entire discussion of

the taxonomy of the Korean legislation. These con-

cepts could optionally appear in some semantic types

but mandatory to the others.

3.1.1 Applicability Condition

The applicability conditions, a.k.a. preconditions,

specify when and under what circumstances a norm

becomes applicable (or activated). In Korean lan-

guage, this can be detected as a phrase or clause that

ends with the following words.

• (where), except the case () (unless, if

not): <situation>

• , , (where/in case):

<situation>

• (in dealing with/when) except the case of

(from the time) and (by the time):

<situation>

• , (a person who. . . ): <a qualification

for individual, or legal entities>.

3.1.2 Legal Effects

Legal effects are the normative effects that follow

from applying a norm, such as obligation, permis-

sion, prohibition, and also other articulated effects in-

troduced for the law (see Sartor, 2005; Rubino et al.,

2006, for details).

While applicability conditions can be optional, le-

gal effects are a mandatory component of every legal

norm.

Figure 1 shows the parse tree for the statement

6

:

“1

”, meaning that “Where a stock

company intends to reduce its capital (

), as prescribed by Presidential Decree (

), in resolving the reduction of its capital

under paragraph (1) (1 ), it

shall obtain approval ( ) from the

Financial Services Commission () in

advance ().” It illustrates how the applicability

conditions and the legal effects that it inferred (in this

case, an obligation to obtain an approval beforehand)

are written in Korean language and how applicability

conditions can be nested together.

From the parse tree, we can also notice that, as

Korean is a left-branching language, the legal effects

always appear as the rightmost component of the tree,

6

This statement is extracted from the 2nd paragraph of

Article 18 in Insurance Business Act. The English transla-

tion available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/law

View.do?hseq=43318&lang=ENG

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

89

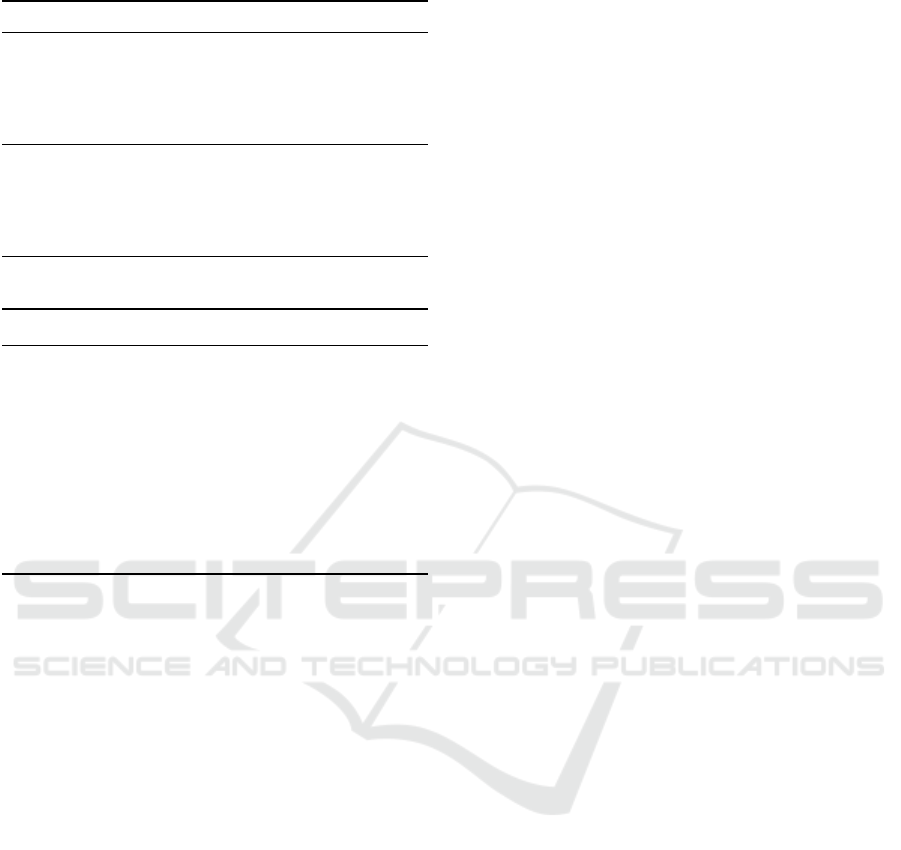

86 ( )

Article 86 (Revocation of Registration)

1 .

1. 842 ᅬ

2. 842

3. 84

4. 2

Where an insurance solicitor falls under any of the following subparagraphs, the Financial Services Commission shall

revoke his or her registration:

1. Where he or she falls under any of the subparagraphs of Article 84 (2);

2. Where he or she is found to fall under any of the subparagraphs of Article 84 (2) as at the time of his or her registration;

3. Where he or she makes a registration under Article 84 by false or other unlawful means;

4. Where he or she is subject to a disposition of business suspension under this Act on at least two occasions.

2 6

. h 2014.1.14i.

1. ᅪ

2. , 1022

3. 1023

Where an insurance solicitor falls under any of the following subparagraphs, the Financial Services Commission may order

him or her to suspend his or her work for the specified period of up to six months, or revoke his or her registration: hAmended

by Act No. 12262, Jan. 14, 2014i

1. Where he or she violates the provisions of this Act governing insurance solicitation;

2. Where he or she, as an insurance policyholder, an insured person or a person that is to receive insurance money,

violates Article 102-2;

3. Where he or she violates Article 102-3;

. . .

[ 2010.7.23]

[This Article Wholly Amended by Act No. 10394, Jul. 23, 2010]

Figure 2: Insurance Business Act: Article 86 (Revocation of Registration) (adopted from: http://www.law.go.kr/ /

, English translation available at: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=43318&lang=ENG).

which is the feature that we use in the NLP classifier

that we developed, and will be discussed in Section 4.

3.1.3 Cross-referencing

Similar to other jurisdictions, legislation in Korean is

divided into parts that promotes clarity for presenta-

tion, structure and expression. As described in (Xan-

thaki, 2014), drafting legislation as this allows legal

drafters to demonstrate the intuition behind the legis-

lation, maintain the coherence of the legislative text,

and can stress the interrelation between different pro-

visions.

As can be seen from Figure 2, the structure

of Korean legislation is comparatively less complex

than legislations of other jurisdictions. In general, a

legislation may consist of different chapters, which

can then be further divided into different articles,

(sub)paragraphs, and items, as shown in Table 1.

7

Ta-

7

Note that the word “” can have multiple meanings

in the Korean language. When used in cross-referencing, it

means to “in the current legislation”.

ble 2 shows some commonly used cross-referencing

patterns in Korean legislation.

8

Besides, when referring to other legislations, the

name of the referred legislations should be enclosed

in square brackets. For instance, “「」” will be

used when referring to the the “Commercial Act”

9

and “「」 2552” will be used when re-

ferring to “Article 255 (2) of the Commercial Act”.

3.2 Semantic Types in Korean

Legislations

When determining the semantic type of a legal state-

ment, it is the legal effects part that plays an impor-

tant role. It specifies the normative effects and the or-

der of validity a legal statement has. Typically, such

provisions have been made transparent by the use of

8

Instead of writing “paragraph #”, in some cases, for

simplicity, the paragraph number will be put inside curly

brackets next to the article number in cross-referencing.

9

The word “” means “Commercial Act” in Korean

language.

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

90

Table 1: Section name and useful terms in Korean language.

Korean

English

Section label

Part

Chapter

Article

Paragraph

Item / Point

Useful term

in the current legislation or

section

starts from

ends with

,

and

Table 2: Cross-referencing Examples.

Example Example (in English)

This Chapter

1 Article 1

322 Article 32 (2)

28 Article 2 (8) point 2

1 2 Paragraph 1 and Paragraph 2

410

412

From Article 420 to Article 412

193ㆍ252

5312

Article 193, Article 252 and Ar-

ticle 532 (2)

modal verbs (Höfler, 2019) that appear at the end of

the statements. Its usage is similar to the words shall

and must in English legislations which show the nat-

ural dispose of a connection to the normative value

contained in the provisions, as well as the normative

functions of these provisions.

Following a functional classification approach, we

have analysed the modal verbs that have been used

in the legal statements and identified eleven differ-

ent categories, i.e., semantic types, that appear in Ko-

rean legislation: Definitional provision, Application

provision, Deeming provision, Continuation clause,

Delegation provision, Penalty provision, and different

types of Deontic provisions, such as Obligation, Lia-

bility, Rights, Permission, and Prohibition. Table 3

show examples of different types of statements ex-

tracted from the Insurance Business Act (IBA). In

what follows, we are going to elicit on each of these

categories.

3.2.1 Definitional Provision

Definitional provisions define commonly used con-

cepts or relevant terms that appear in (and in some

cases, specific to) the legislation.

In Korean legislation, it uses “X / . . .Y

/ ” to denote the pattern “X means Y ”.

where X is called a definiendum which can be a word,

a phrase, or a symbol, and is normally enclosed in-

side double quotes, Y is called a definien and is used

to describe/define the definiendum X.

Notice that definitional provisions, in general, do

not contain any applicability condition as the terms

was defined in a general sense (within the context

of the legislation) and, unless otherwise specified, it

should be used without any restriction.

3.2.2 Application Provision

Application provisions set out situations or time-

frames in which the law, or section(s) of law, applies

( (shall apply), or (shall be gov-

erned by)), applies with some changes (

(shall apply mutatis muntandis)), or does not apply

(/ ).

In some cases, an application provision may also

be used to specify the statuses (and/or timeframes) of

other legislations.

3.2.3 Deeming Provision

A deeming provision indicates something to be

deemed or construed (() ) as if something

else (through cross-referencing) if the two can be con-

strued as the same thing, or the later inherits some

qualities that the former does not have. In the same

vein, a deeming provision can also be used to in-

dicates something cannot be deemed or construed

(() ) as something else.

However, latest research found that a deeming

provision may deem things to be what they are

not (Bracher, 2018). To resolve this issue, it is manda-

tory that a deeming provision should always be con-

strued on its own terms under the context concerned

and purposes of the legislation.

3.2.4 Continuation Clause

A continuation clause is a provision that is used to

extend or limit the scope of application of a precedent

legal statement. It is expected that, unless otherwise

specified, the legal effects inferred by the continuation

clause will be the same as ( ), or applies to

the same objects ( ) as the original statement.

3.2.5 Delegation Provision

Under normal situations, a person who is vested with

a particular statutory power, duty, or function may ex-

ercise it himself/herself. However, for the sake of

convenience in practice, a power, duty or function

may be delegated pursuant to an instrument of dele-

gation through a delegation provision and exercise the

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

91

Table 3: Example of semantic types of norms from the Insurance Business Act (the full Act is available at:

http://www.law.go.kr//, English translation available at: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hse

q=43318&lang=ENG).

Semantic type Example (Korean) Example (translation in English)

Definitional provision “” ᅪ

,

.

The term “life insurance business” means the business of un-

derwriting insurance, receiving premiums, paying insurance pro-

ceeds, etc. which arise in selling life insurance products.

Application provision (催告)

ᅪ 「」 353 .

Article 353 of the Act on Corporate Governance of Financial

Companies shall apply mutatis mutandis to mutual companies.

Deeming provision “” “” . In such cases, “insurance company” shall be construed as “sub-

sidiary”.

Continuation clause ᅬ . This shall also apply where it decides not to transfer its insurance

contracts.

Delegation provision 1 2 ᅪ

.

Necessary matters concerning procedures for and methods of pay-

ing contributions under paragraphs (1) and (2) shall be prescribed

by Presidential Decree.

Penalty provision 911 ᅪ ᅪ

832 100

1 .

Where an insurance agency, etc. of a financial institution pre-

scribed in Article 91 (1) or a person that intends to become an

insurance agency, etc. of a financial institution violates Article 83

(2) or 100, he/she or it shall be punished by an administrative fine

not exceeding 100 million won.

Deontic provisions

Obligation ᅪ

. . . .

The insurance association shall perform any of the following af-

fairs, as prescribed by the articles of association: . . .

Liabilities ᅪ

.

The liability of the members of every mutual company for the

debts of their company shall be limited to their insurance premi-

ums.

Rights

.

A policyholder or a person who is to receive insurance proceeds

is entitled to be paid the amount accumulated for the insured in

preference to any other creditors from assets deposited by the rel-

evant stock company pursuant to orders issued by the Financial

Services Commission under this Act.

Permission . A stock company may convert its organization into a mutual com-

pany.

Prohibition

ᅬ .

An insurance agency or insurance broker shall not be mainly en-

gaged in soliciting any insurance contract which is to make him-

self/herself or a person who employs himself/herself as the poli-

cyholder or the insured.

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

92

power in the name of the delegated (Victorian Gov-

ernment Solicitor’s Office, 2008).

A delegation provision should state clearly the na-

ture of powers, duties, or functions being delegated,

as well as the entitlements, conditions, and restric-

tions that it may have on the delegate. In Korean

legislation, it can be distinguished by the phrases:

()/ (shall be prescribed by), or /

(shall be determined and an-

nounced).

3.2.6 Penalty Provision

The primary function of a penalty provision is to stip-

ulate potential consequences (legal effects) when a

breach of legislation, i.e., a violation of a prescribed

requirement, or non-performance of an obligation has

occurred, and it can be identified with the phrases:

, , , or

(shall be punished).

Besides, a penalty provision may also stipulate

the conditions under which a government agency

may/shall revoke, suspend, or cancel the penalties

stipulated by the legislation ( (may

revoke/suspend/cancel) or (shall

revoke/suspend/cancel)).

3.2.7 Deontic Provision

Deontic concepts of obligations, dispensations (ex-

ception from obligations), liabilities, rights, permis-

sions, and prohibitions are important concepts in le-

galisms and legal reasonings, and is used to manipu-

late or restrict the behaviour of an entity.

For one, the use of (shall do) in Korean

legislation makes it clear that an entity has an obliga-

tions (i.e., a duty to comply), or committing herself to

such action. Whilst the provision indicates a specific

state a legal entity should be into, the phrase

(shall be a juristic person) is used. If the pro-

vision, however, requires an entity to carry out some

specific actions, then the phrase (shall

perform tasks) will be used instead.

In addition to this, the following phrases are used

to determine the liabilities of an entity:

(shall take responsibility), . . . (may

not be released from responsibility), . . .

(the liability shall be limited to), and

(may not take any responsibility).

Rights, on the other hand, dictate the principle of

entitlement that one may have under some specific

conditions and cannot be infringed by other person,

government, or authorities, and are expressed with the

phrases: / (is entitled/have the right

to), . . . (rights and duties

shall be succeeded).

Similarly, permissions refer to a licence to do

something, or in some cases, an entity is authorised

to do an act which, in principle, without such author-

ities, such actions would have been unlawful.

10

In

Korean language, this can be identified by the terms

ㄹ or (may do).

From a legal reasoning perspective, both permis-

sions and rights are similar in nature as they can be

considered as a dual of obligations i.e., if an entity

has the obligation to perform a task, then she should

have the permission (or right) to carry out such task

(note that the reverse might not be true). The main

difference between the two is that the entitlement en-

joyed by an entity under rights cannot be infringed

or retract; while the case for permissions may still be

subject to other conditions as prescribed in the legis-

lation.

Lastly, prohibitions prescribe the states or actions

that should not be undertaken by a legal entity or a vi-

olation will appear. It can be identified by the phrases:

ᅬ (no. . . shall do), (shall be prohib-

ited), and (not permitted).

Table 4 shows a summary of semantic types and

their corresponding terminologies in Korean legisla-

tion.

4 EXPERIMENTAL ANALYSIS

4.1 Dataset

To evaluate the taxonomy discussed in the previous

section, an empirical analysis has been undertaken.

The used dataset comprises 1,237 sentences which

constitute the statements from three different Korean

legislations, namely: Insurance Business Act (IBA),

Banking Act (BA), and Financial Holding Companies

Act (FHCA).

In the preprocessing phase, the raw text of these

legislations was segmented into sentences. As sen-

tences in the Korean language are ended with a pe-

riod, punctuation marks e.g. comma, colons, semi-

colons, etc., will be ignored. In the case of enumer-

ations or lists, the same rule is applied. That is, all

10

Notice however that, in the literature, there are some

discussions in the legal reasoning domain that explicitly

permitting an action makes little sense when such action has

not (generally) been prohibited before. Besides, such per-

mission may limit the effects of an obligation (or a prohibi-

tion). As the discussion of this topic is outside the scope of

this paper, we refer the interested reader to (Hansen, 2014)

for details.

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

93

Table 4: Semantic types and their corresponding terminol-

ogy in Korean Legislations.

Term Description

Definitional provision

1.1 / means

Application provision

2.1 shall apply mutatis

muntandis

2.2 shall apply

2.3 shall / does not apply

2.4 shall be governed by

Deeming provision

3.1 () shall be deemed

shall be construed

3.2 () shall not be deemed

shall not be construed

Continuation clause

4.1 the same as

4.2 shall also apply

Delegation provision

5.1 ()/ shall be prescribed by

5.2 shall be entrusted

Penalty provision

6.1 shall be punished

(科)

6.2 a fine may be imposed

(倂科)

6.3

may impose a penalty sur-

charge

Obligation

7.1 shall do

7.2 shall take responsibility

Liabilities

8.1 . . . the liability shall be lim-

ited to

8.2

may not take any responsi-

bility for

8.3 shall take responsibility

Rights

9.1 / is entitled, have the right

Permission

10.1 ㄹ/ may do

Prohibition

11.1 ᅬ No . . . shall do

11.2 shall not do

11.3 No. . . may do, may not do

11.5 shall be prohibited

items in an enumeration or a list will be considered

as a single sentence unless one of them ended with a

period.

Next, all sentences were manually classified by

the domain experts, according to the taxonomy dis-

cussed in Section 3. Table 5 shows the semantic types

distributions in each of the legislations and their total

occurrences in the dataset. As can be seen, some types

appear regularly, e.g., definitional provisions, applica-

tion provisions and most types of deontic provisions,

whereas some have very low support, e.g., deeming

provisions, continuation clauses, rights, and liabili-

ties. However, as are common in other legislations,

the three types of deontic provision, namely: obliga-

tions, permissions, and prohibitions together consti-

tute to more than half of the statements found in the

three legislations.

4.2 Evaluation Results

To evaluate the taxonomy of automated legal norms

classification, a NLP classifier based on regular ex-

pressions has been developed. In each iteration, a

statement from the dataset is selected and passed to

the syntax tree generator, Komoran3, mentioned be-

fore. The resulting parse tree is then analysed and the

semantic type of the statement is determined through

applying the regular expression rules to the legal ef-

fect component of the tree.

The results are shown on the right hand side of

Table 5. Thereby, different semantic types are differ-

entiated, and the precision and recall are determined

for every type individually. As evidenced by the re-

sults, the taxonomy presented in the previous section

can help in effectively classifying the semantic types

of statements in the Korean legislation with only lim-

ited issues appeared. This is due to the fact that legal

statements are often written in boilerplate expressions

where a fixed set of terminologies was used. In short,

a total of 1,190 statements has been correctly classi-

fied with an overall precision and recall rate of 0.99

and 0.96, respectively.

For the statements that cannot be classified cor-

rectly, we found that they were mostly due to either

the statements were so complex such that the rules

that we defined in the regular expressions are not ca-

pable to handle, or the taxonomy terms have appeared

at some places other than the main paragraph, which

negatively impacted the performance of the classifier.

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

94

Table 5: Semantic types distribution of statements.

Semantic type IBA BA FHCA

Total

Occurrences

Precision Recall F

1

score

Definitional provisions 20 11 10 41 1.00 1.00 1.00

Application provisions 101 35 47 183 0.98 0.98 0.98

Deeming provisions 22 5 8 35 0.95 1.00 0.97

Continuation clauses 6 0 1 7 1.00 1.00 1.00

Delegation provisions 42 23 22 87 1.00 0.99 0.99

Penalty provisions 34 27 23 84 0.99 0.89 0.94

Deontic provisions

Obligations 192 113 87 392 0.99 0.93 0.96

Liabilities 4 0 1 5 1.00 1.00 1.00

Rights 6 0 0 6 1.00 1.00 1.00

Permissions 114 79 71 264 0.97 0.99 0.98

Prohibitions 59 32 42 133 1.00 0.98 0.99

Total 600 325 312 1237 0.99 0.96 0.97

5 RELATED WORKS

The development of legal taxonomies and ontologies

have received unprecedented attention, and various

dedicated works has been proposed in the past two

decades. For instance, Hachey and Grover (2004)

presented an early attempt to address the legal norm

classification problem. In the paper, the authors have

classified statements from the judgements of the UK

House of Lords according to their rhetorical role.

Merchant and Pande (2018), on the other hand, pro-

posed an approach to summarize legal judgements

based on latent semantic analysis (Foltz, 2001), and

was able to achieve an average ROGUE-1 score of

0.58.

Zeni et al. (2015), on the other hand, pro-

posed a framework, GauiT 2.0, to semi-automate

the legal concepts extraction and annotation process.

Boella et al. (2013) presented a rather similar ap-

proach which automatically extract semantic knowl-

edge from legal texts based on the syntactic depen-

dencies between different lexical terms. However,

the downside of these studies is that they still need

substantial manual efforts and time to prepare, model

training and development.

Likewise, the development of several ontolo-

gies notably IPROnto (Delgado et al., 2003), FO-

LAW (Valente et al., 1999), PRONTO (Palmirani

et al., 2018), DOCLE/DOCLE

+

(Gangemi, 2007),

etc., have been reported. The PRONTO, a legal on-

tology on GDPR, provides the legal knowledge mod-

elling of the privacy agents, data types, types of pro-

cessing operations, rights and obligations. Contrary

to HL7 privacy ontology

11

to manage the health data

11

https://wiki.hl7.org/index.php?title=Security_and_Pri

vacy_Ontology

for electronic health records, the goal of PRONTO

ontology is to support the legal reasoning using de-

feasible logic theory. Rubino et al. (2006) pre-

sented an OWL-DL based ontology of basic legal

concepts (Sartor, 2006) such as obligations, per-

missions, rights, erga-omnes rights, liabilities, legal

power. While these studies are relevant to our work

but their goal different from ours – in particular, the

focus of PRONTO ontology is limited to privacy and

data rights in the context of GDPR. Whereas, Ru-

bino’s work is limited as they only extract basic legal

concepts.

Recently, the use of NLP techniques to automate

the legal norms classifications process has been ad-

vocated. For instance, Sleimi et al. (2018) used NLP

techniques to extract the legal provisions information

such as modalities, actors, conditions, exceptions and

violations. Hwang et al. (2018) used NLP tools and

data mining techniques and extracted legal as well as

domain-relative terms from the Chinese regulations

and legal sources and constructed a legal ontology

with legal terms and definitions from the Taiwan leg-

islation. They considered the related attributed and

relationships among the keywords and extracted 1114

legal terms and relevant definitions interpreted by the

domain experts from more than 15 patterns in the Tai-

wan’s law and regulations.

The work of Waltl et al. (2019) is closely related

to us. In the paper, the authors have applied both rule-

based and machine learning approach and classified

German Civil Law into 9 different semantic types.

such as duties, prohibitions, permission, etc. We share

the common objective with these works in the context

of constructing the legal knowledge ontological graph

from the Korean legal sources; however, the work of

Waltl et al. is limited in scope as we consider more

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

95

granular functional aspects of the Korean legislation,

which results in 12 different semantic types.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, extracting normative information cap-

tured in a legal document is a time-consuming and

error-prone task. The taxonomy presented in this pa-

per has filled a gap to legislation written in the Korean

language, and to the best of our knowledge, is the first

of its kind.

For future work, we plan to extend the taxonomy

to cater to the wider needs of the Korean legislations

analysis and investigate different NLP approaches to

automate the legal norms formulation (or translation)

process so that a machine understandable formalism

can be inferred directly from the Korean statutory

texts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kiet Hoang The and

Wooseok Kim for helping with this project, Gabriela

Ferraro for her fruitful comment and suggestions to

improve the quality of the paper.

REFERENCES

Boella, G., Di Caro, L., and Robaldo, L. (2013). Semantic

Relation Extraction from Legislative Text Using Gen-

eralized Syntactic Dependencies and Support Vector

Machines. In RuleML 2013, pages 218–225.

Bojanowski, P., Grave, E., Joulin, A., and Mikolov, T.

(2016). Enriching word vectors with subword infor-

mation.

Botha, J. and Blunsom, P. (2014). Compositional morphol-

ogy for word representations and language modelling.

In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference

on Machine Learning, page 1899–1907.

Bracher, P. (2018). Interpretation: The nature of a deem-

ing provision. https://www.financialinstitutionslegals

napshot.com/2018/04/interpretation-the-nature-of-a

-deeming-provision/. [accessed: 29 June 2020].

Casanovas, P. (2019). Legal Linked Data Ecosystems and

the Rule of Law, chapter Legal Linked Data Ecosys-

temsand the Rule of Law, pages 87–126. Springer.

Ceci, M., Khalil, F. A., and O’Brien, L. (2016). Making

Sense of Regulations with SBVR. In Proceedings

of the RuleML 2016 Challenge, Doctoral Consortium

and Industry Track.

Choi, M., Hur, J., and Jang, M.-G. (2004). Constructing

Korean Lexical Concept Network for Encyclopedia

Question-Answering System. In Proceedings of the

30th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electron-

ics Society, volume 3, pages 3115–3119. IEEE.

Cotterell, R. and Schütze, H. (2015). Morphological word-

embeddings. In NAACL 2015, page 1287–1292.

Delgado, J., Gallego, I., Llorente, S., and Garcia, R. (2003).

IPROnto: An Ontology for Digital Rights Manage-

ment. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference

on Legal Knowledge and Information Systems.

Dragoni, M., Villata, S., Rizzi, W., and Governatori, G.

(2015). Combining Natural Language Processing Ap-

proaches for Rule Extraction from Legal Documents.

In AI Approaches to the Complexity of Legal Systems

International Workshops, pages 287–300.

Ferraro, G., Lam, H.-P., Colombo Tosatto, S., Oliveri, F.,

van Beest, N., and Governatori, G. (2019). Auto-

matic Extraction of Legal Norms: Evaluation of Nat-

ural Language Processing Tools. In JURISIN 2019,

Kanagawa, Japan. Springer.

Foltz, P. (2001). Semantic Processing: Statistical Ap-

proaches. In International Encyclopedia of the Social

and Behavioral Sciences, pages 13873 – 13878.

Gangemi, A. (2007). Design Patterns for Legal Ontology

Constructions. In LOAIT 2007, pages 65–85.

Gordon, T. F., Governatori, G., and Rotolo, A. (2009).

Rules and Norms: Requirements for Rule Interchange

Languages in the Legal Domain. In RuleML 2009,

pages 282–296.

Hachey, B. and Grover, C. (2004). Sentence Classification

Experiments for Legal Text Summarisation. In The

17th Annual Conference on Legal Knowledgeand In-

formation Systems, JURIX 2004. IOS Press.

Hansen, J. (2014). Reasoning About Permission and Obli-

gation. In David Makinson on Classical Methods

for Non-Classical Problems, volume 3 of Outstanding

Contributions to Logic, pages 287–333.

Hashmi, M., Casanovas Romeu, P., and de Koker, L. (2018).

Legal Compliance Through Design: Preliminary Re-

sults of a Literature Survey. In TERECOM 2018,

pages 59–72.

Hashmi, M., Governatori, G., and Wynn, M. T. (2013). Nor-

mative Requirements for Business Process Compli-

ance. In Proceedings of the 3rd Australasian Sympo-

sium on Service Research and Innovation, pages 100–

116.

Hilty, M., Basin, D., and Pretschner, A. (2005). On Obli-

gations. In Proceedings of the 10th European Sym-

posium on Research in Computer Security, ESORICS

2005, pages 98–117, Milan, Italy.

Hoekstra, R., Breuker, J., Bello, M. D., and Boer, A. (2007).

The LKIF Core Ontology of Basic Legal Concepts. In

Proceedings of the Workshop on Legal Ontologies and

Artificial Intelligence Techniques, pages 43–63.

Höfler, S. (2019). Making the law more transparent: Text

linguistics for legislative drafting. In Legal linguis-

tics beyond borders: Language and law in a world of

media, globalisation and social conflicts, pages 229–

252.

Hwang, R.-H., Hsueh, Y.-L., and Chang, Y.-T. (2018).

Building a Taiwan Law Ontology Based on Automatic

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

96

Legal Definition Extraction. Applied System Innova-

tion, 1(3):22.

Jeong, H., Sugiura, M., Sassa, Y., Haji, T., Usui, N., Taira,

M., Horie, K., Sato, S., and Kawashima, R. (2007).

Effect of syntactic similarity on cortical activation

during second language processing: A comparison

of English and Japanese among native Korean trilin-

guals. Human Brain Mapping, 28(3):194–204.

Junho, J. P., Jo, Y., and Shin, H. (2010). The KOLON

System: Tools for Ontological Natural Language Pro-

cessing in Korean. In JUCLIC 2010, pages 425–432.

Karkkainen, B. C. (1994). Plain Meaning: Justice Scalia’s

Jurisprudence of Strict Statutory Construction. Har-

vard Journal of Law & Public Policy, 17(2):401–477.

Lam, H.-P. and Hashmi, M. (2019). Enabling Reasoning

with LegalRuleML. Theory and Practice of Logic

Programming, 19(1):1–26.

Lee, D. (2018). Morpheme-based Efficient Korean Word

Embedding. MSc. Thesis, Seoul National University,

Seoul, South Korea.

Marín, R. H. and Sartor, G. (1999). Time and Norms: A

Formalisation in the Event-Calculus. In ICAIL ’99,

page 90–99.

Mattei, U. (1997). Three Patterns of Law: Taxonomy and

Change in the World’s Legal Systems. The American

Journal of Comparative Law, 45(1):5–44.

Matteson, A., Lee, C., Kim, Y., and Lim, H. (2018). Rich

Character-Level Information for Korean Morphologi-

cal Analysis and Part-of-Speech Tagging. In COLING

2018, pages 2482–2492.

McCarty, L. T. (1989). A Language for Legal Discourse: I.

Basic Features. In ICAIL ’89, page 180–189.

McGregor, B. (2005). Constructing a concise medical tax-

onomy. Journal of the Medical Library Association,

93(1):121–123.

Merchant, K. and Pande, Y. (2018). NLP Based Latent Se-

mantic Analysis for Legal Text Summarization. In

2018 International Conference on Advances in Com-

puting, Communications and Informatics, ICACCI

2018, pages 1803–1807.

Mills, A. (2014). Rethinking Jurisdiction in Interna-

tional Law. British Yearbook of International Law,

84(1):187–239.

Müller-Gotama, F. (1994). The cross-linguistic survey. In

Grammatical Relations: A Cross-Linguistic Perspec-

tive on their Syntax and Semantics, pages 78 – 140.

Ock, C. (2013). UWordMap. University of Ulsan, Ulsan,

South Korea.

Palmirani, M., Governatori, G., and Contissa, G. (2011).

Modelling temporal legal rules. In The 13th Interna-

tional Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law,

Proceedings of the Conference, pages 131–135.

Palmirani, M., Martoni, M., Rossi, A., Bartolini, C., and

Robaldo, L. (2018). PrOnto: Privacy Ontology for Le-

gal Reasoning. In K

˝

o, A. and Francesconi, E., editors,

Electronic Government and the Information Systems

Perspective, pages 139–152. Springer.

Prakken, H. and Sartor, G. (1996). A Dialectical Model of

Assessing Conflicting Arguments in Legal Reasoning.

Artificial Intelligence and Law, 4(3):331–368.

Rubino, R., Rotolo, A., and Sartor, G. (2006). An OWL

Ontology of Fundamental Legal Concepts. In JURIX

2006, pages 101–110.

Sartor, G. (1992). Normative conflicts in legal reasoning.

Artificial Intelligence and Law, 1(2-3):209–235.

Sartor, G. (2005). Legal Reasoning: A Cognitive Approach

to the Law, volume 5 of A Treatise of Legal Philoso-

phy and General Jurisprudence. Springer.

Sartor, G. (2008). Legal Validity: An Inferential Analysis.

Ratio Juris, 21(2):212–247.

Sleimi, A., Sannier, N., Sabetzadeh, M., Briand, L. C., and

Dann, J. (2018). Automated Extraction of Semantic

Legal Metadata Using Natural Language Processing.

In RE 2018, pages 124–135.

Song, H.-J. and Park, S.-B. (2019). Korean Morphological

Analysis with Tied Sequence-to-Sequence Multi-Task

Model. In EMNLP-IJCNL 2019, pages 1436–1441.

Stratos, K. (2017). A Sub-Character Architecture for Ko-

rean Language Processing. In EMNLP 2017, page

721–726.

Valente, A., Breuker, J., and Brouwer, B. (1999). Legal

modeling and automated reasoning with ON-LINE.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

51(6):1079 – 1125.

van Engers, T. M., van Gog, R., and Sayah, K. (2004). A

Case Study on Automated Norm Extraction. In JURIX

2004, pages 49–58.

Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office (2008). Current Is-

sues in Delegations. In Clent Newsletter, Administra-

tive Law. [accessed: 30 June 2020].

von Wright, G. H. (1963). Norm and action: a logical en-

quiry. Routledge, London.

Waltl, B., Bonczek, G., Scepankova, E., and Matthes, F.

(2019). Semantic types of legal norms in German

laws: classification and analysis using local linear ex-

planations. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 27(1):43–

71.

Wieringa, R. J. and Meyer, J.-J. C. (1993). Applications

of Deontic Logic in Computer Science: A Concise

Overview. In International Workshop on Deontic

Logic in Computer Science, pages 17–40.

Wieting, J., Bansal, M., Gimpel, K., and Livescu, K. (2016).

Charagram: Embedding Words and Sentences via

Character n-grams. In EMNLP 2016, pages 1504–

1515.

Wyner, A. and Peters, W. (2011). On Rule Extraction from

Regulations. In JURIX 2011, pages 113–122.

Xanthaki, H. (2014). Structure of a Bill. In Drafting Leg-

islation: Art and Technology of Rules for Regulation.

Hart Publishing.

Yoon, A.-S., Hwang, S.-H., Lee, E.-R., and Kwon, H.-C.

(2009). Construction of Korean Wordnet “KorLex

1.5”. Journal of KIISE: Software and Applications,

36(1):92–108.

Zeni, N., Kiyavitskaya, N., Mich, L., Cordy, J. R., and My-

lopoulos, J. (2015). GaiusT: supporting the extraction

of rights and obligations for regulatory compliance.

Requirements Engineering, 20(1):1–22.

Towards Construction of Legal Ontology for Korean Legislation

97