Challenges in Public Participation and Collaboration: A Case Study

in Finnish Environmental Decision-making

Annamaija Paunu, Jenni Pansio, Nina Helander and Jonna Käpylä

Information and Knowledge Management, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Keywords: Multistakeholder Collaboration, Knowledge Sharing, Communication, Public Participation Process, Impact

Assessment Process, Collaborative Governance.

Abstract: This position paper introduces ongoing research efforts that addresses the ability of different kinds of

organizations and multiple individuals to cope together with complex environmental planning and policy-

making problems in the Finnish context. The research question “What kind of challenges are there in the

collaborative processes of environmental decision-making and how can they be tackled?” is approached from

the perspectives of the framework of public participation process and the theory of collaborative governance.

We use these theories as analytical tools to evaluate how the elements and phases of collaboration processes

are conducted in practice and to identify problems that exist in the collaborative processes. This phenomenon

is studied through a single case study of environmental planning case from a medium-sized city located in

Finland.

1 INTRODUCTION

How collaborative processes should be implemented

is widely discussed in the literature (e.g. Irvin &

Stansbury, 2004; Brinkerhoff & Azfar, 2006;

Godenhjelm & Johanson, 2018). For example, the

framework of public participation process (Bryson et

al. 2013) and the theory of collaborative governance

(Ansell & Gash 2008) describe the characteristics of

participative actions and what should be considered

when developing and conducting these kinds of

processes. However, more research is needed about

the actual empirical practice of collaboration

(Sotarauta, 2010).

In this paper, we aim to shed light on the actual

practice of collaboration throuh a case study and

answer the research question: “What kind of

challenges are there in the collaborative processes of

environmental decision-making and how can they be

tackled?” We approach this from the perspectives of

the framework of public participation process and the

theory of collaborative governance. We use these

theories as analytical tools to evaluate how the

elements and phases of collaboration processes are

conducted in practice and to identify problems that

exist in the collaborative processes. We aim to

broaden the current understanding of how to

implement successful collaborative processes by

identifying problems in the processes and by offering

preliminary ideas about the means to avoid these

problems to emerge.

This position paper introduces ongoing research

efforts included in the ambitious research project

CORE: Collaborative remedies for fragmented

societies — Facilitating the collaborative turn in

environmental decision-making (CORE 2018).

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Spatial Planning and Participation

In Finland, stakeholder involvement to the master

planning process is required by law. The law

obligates municipalities to involve and hear all who

are affected by the plan during the master planning

process to ensure planning being based on timely

information and knowledge, and that the plans are

serving the needs and aims of the municipality in best

possible manner. The plans are required to be kept

updated and changed when needed, and all changes

require informing those affected by the changes.

Master planning process affects and includes

172

Paunu, A., Pansio, J., Helander, N. and Käpylä, J.

Challenges in Public Participation and Collaboration: A Case Study in Finnish Environmental Decision-making.

DOI: 10.5220/0010128301720179

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2020) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 172-179

ISBN: 978-989-758-474-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

involving several different stakeholder groups, from

citizens to local public administration, partners,

media, and decision-makers. However, it is not

specified in the law how the stakeholders should be

involved or heard, which leaves room for different

interpretations and implementation. (ELY, 2017).

Traditionally, stakeholders and especially citizens,

are involved in the early stages of the master planning

process, where in the beginning of the process

municipalities make a law-required participation and

assessment scheme (OAS), which describes

stakeholder involvement, interaction and impact

assessment in the process. The stakeholder groups are

expected to comment and suggest changes to the OAS

in case the planned procedures are considered

insufficient, which leads to a requirement of making

supplements to the OAS. Next to commenting the

OAS, the stakeholders can make planning initiatives

and proposals, participate in hearings about

preparation materials of the master plan, and in later

phases make a reminder to the municipality when

disagreeing with the plan or at the end of the process,

appeal to administrative court. (ELY, 2017).

2.2 Public Participation Process

The value of public participation is broadly

recognized for various purposes, however, how to

successfully apply public participation processes to

decision-making is a challenge that should not be

overlooked; at its best, public participation may lead

for example to strengthened democracy, increased

trust, knowledge flows and joint knowledge creation.

On the other hand, unsuccessful public participation

is known to cause resentment, mistrust and conflicts,

that might hinder current and also future collaborative

actions. (Irvin & Stansbury, 2004; Ansell & Gash,

2008; Gaventa & Barrett, 2012).

Bryson et al (2013) reviewed systematically more

than 250 articles and books related to the phenomena

and designed guidelines for public participation

process combined with their own experiences (Bryson

et al, 2013). The design guidelines are a synthesis for

creating, managing and evaluating public participation

activities in order to accomplish desired outcomes.

They form a process, that I) assesses the context and

problem, and designs the participation process based

on context-specifically identified purposes, II)

manages the resources available and stakeholder

participation throughout the process by utilizing

effective leadership, establishing rules and structures,

analyze-based appropriate stakeholder involvement,

engaging diversity, and managing power dynamics,

and III) evaluates and redesigns the process

continuously to develop by using evaluation measure.

The twelve tasks, or outlines, if one will, are

categorized into above-mentioned three classes

covering the assessment and design, the managing and

resourcing, and the evaluating of the project. These

outlines are not step by step tasks, instead tasks like for

example identifying purpose or managing power

dynamics need to be evaluated and iterated through the

process to be able to achieve the joined target. The

framework balances between design science literature

and evidence-based research findings giving the

outcome that successful public participation requires

designing iteratively, in response to specific purposes

and contexts (Bryson et al, 2013). This process aims

to respond in practical manner to the complexities and

tackle the process design issues acknowledged in

designing public participation processes. (Bryson et al,

2013).

2.3 Collaborative Governance

The concept of collaborative governance is rather

fuzzy, as the current definitions can be considered to

some extent vague and open for interpretations.

Therefore, the understanding of collaborative

governance varies, as do the implementations.

However, in the scholarly discourse the definition of

collaborative governance appears unanimous.

(Batory & Svensson, 2019). Despite of different

emphasizes on the definitions, there can be

recognized some key themes, that give outlines to the

concept of collaborative governance (not in specific

order): 1) distribution of power, 2) balance of roles,

3) communication, and 4) working jointly towards

solutions through learning.

The distribution of power consists of the need of

strong leadership for the process to facilitate and

guide it through and to empower stakeholder groups,

but also, that everyone affected by the decisions made

should be involved to the decision-making process.

With power should also come responsibility, which

engages the stakeholders by creating ownership and

gives the experience of meaningfulness for the

participation to the stakeholder groups and builds up

trust. The power is distributed in practice through

partnerships and/or networking. In the relationships

between different stakeholder groups is important the

balance of the roles, meaning each stakeholder group

being heard equally in the decision-making and

avoiding the dominance of some groups over others.

Networking brings together local tacit knowledge and

science, and by open discussion can be created

knowledge flows and emerge new knowledge. Open

communication, with knowledge flows and

Challenges in Public Participation and Collaboration: A Case Study in Finnish Environmental Decision-making

173

knowledge co-creation, provides opportunities for

finding solutions, that would not have been possible

without collaboration. Collaborative process should

also include reflection to enhance the collaboration

through and during the process, which enables social

learning and increases the capability of solving ever

more complex issues. (Emerson et al, 2012; Hotte,

Kozak & Wyatt 2019; Berkes, 2009; Leino, 2019;

Ansell & Gash, 2008).

However, having a functioning collaborative

governance process is not something to take for

granted, but there lay several challenges. The

distribution of power engages the stakeholders, which

is favorable for trust-building, commitment and

learning, but increased feeling of ownership amongst

several stakeholder groups may lead into conflicts, as

well as to imbalance of roles. Also, only a seeming

process with no impact or power in the stakeholders’

aspects brought up, may lead to mistrust and

conflicts. Strong, but empowering leadership is

needed to manage possible conflicts and negotiations

during the process, but especially communication is

in an important role to establish and run the process

successfully. Open communication, especially face to

face, throughout the process and when jointly sharing

expectations, creating aims and internal rules for the

collaboration amongst the stakeholders, can be

increased trust but also engage the stakeholders, and

lower the risk of conflicts. At its best, in the long run

increased trust, mutual contracts and improved

knowledge flows lead to lesser conflicts and higher

legitimacy of the decisions made, but even moreover,

jointly creating solutions that were not possible to be

created without the collaboration. (Emerson et al,

2012; Hotte, Kozak & Wyatt 2019; Berkes, 2009;

Leino, 2019; Ansell & Gash, 2008).

3 RESEARCH METHOD

3.1 Case Lahti

In this paper the collaborative process in

environmental decision making is examined by

applying case study methodology. The case is a

medium-sized city in Finland and its municipal

master plan process.

The complexity of spatial planning formulates of

being a strategic tool, which however consists of non-

strategic instruments such as handling property rights,

protecting the environment from change and

displaying legal validity and political authority. This

has led spatial planning being considered heavy and

restrictive. In Lahti the traditionally restrictive master

planning process has been turned innovatively into a

resource and opportunities, by practicing strategic

incrementalism in spatial planning and participative

strategic leadership in managing the city. (Mäntysalo

et al, 2019). The city has planned and performed a

continuous master plan process, which is tightly

connected with the city councils working period of

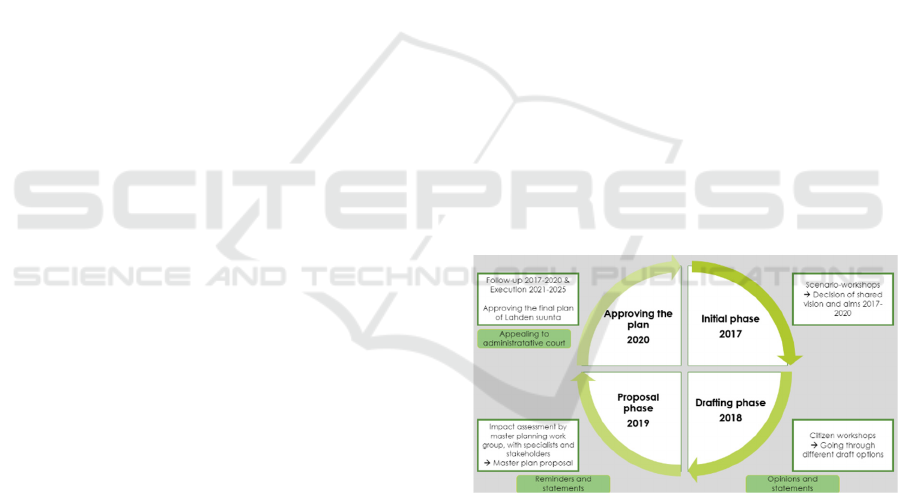

four years and the city’s own strategy work (Figure

1). In its strategy, Lahti has defined the citizens as the

makers of the city and committed in citizen

participation and involvement in decision-making to

reach the development goals set for the city by 2030,

which includes also the spatial planning of the city

(Tuomisaari, 2019). The case concentrates on the

third ongoing master plan process and especially to

its impact assessment process.

Impact assessment takes place on the third year of

the master planning process, and it has been

previously led by a group of specialists, and

representatives of the city from different fields have

joined the impact assessment process in two

workshops and via an online platform. (Palomäki,

2018). However, on the third ongoing master

planning process next to the specialists and city

representatives, there was invited representatives of

third sector organizations, who were chosen based on

a close interest towards the themes.

(Interviews with

Lahden suunta representatives, 2020; Interviews with

impact assessment participants, 2019).

Figure 1: Process chart of the four-year process of Lahden

suunta (Created based on the text and graph in Lahden

suunta OAS, 2019, p. 4, translated from Finnish).

3.2 Empirical Data

Empirical data (see Table 1) of the case includes

observation data from two impact assessment

seminars, interview data of seven participants; 4

participants representing stakeholders and experts, 2

employees of Lahti (Lahti master planner and Lahti

interaction designer) and former Lahti master

planner. We also study documents provided by city of

Lahti; such as the master plan drafts commentary (15

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

174

statements and 80 opinions) and responses from city

of Lahti. The data was analyzed using content

analysis. Content analysis can be used to analyze both

qualitative and qualitative data, although it is more

known method in qualitative research. In this case

study we used both qualitative and quantitative data

to gain range and depth to form a holistic

understanding on the case (Fielding and Fielding,

1986). Each data was analyzed deductively (Elo &

Kyngäs, 2008; Tuomi & Sarajärvi 2018) by using the

design guidelines by Bryson et al (2013) and the key

themes of collaborative governance, and summarized

into table in Chapter 4.1.

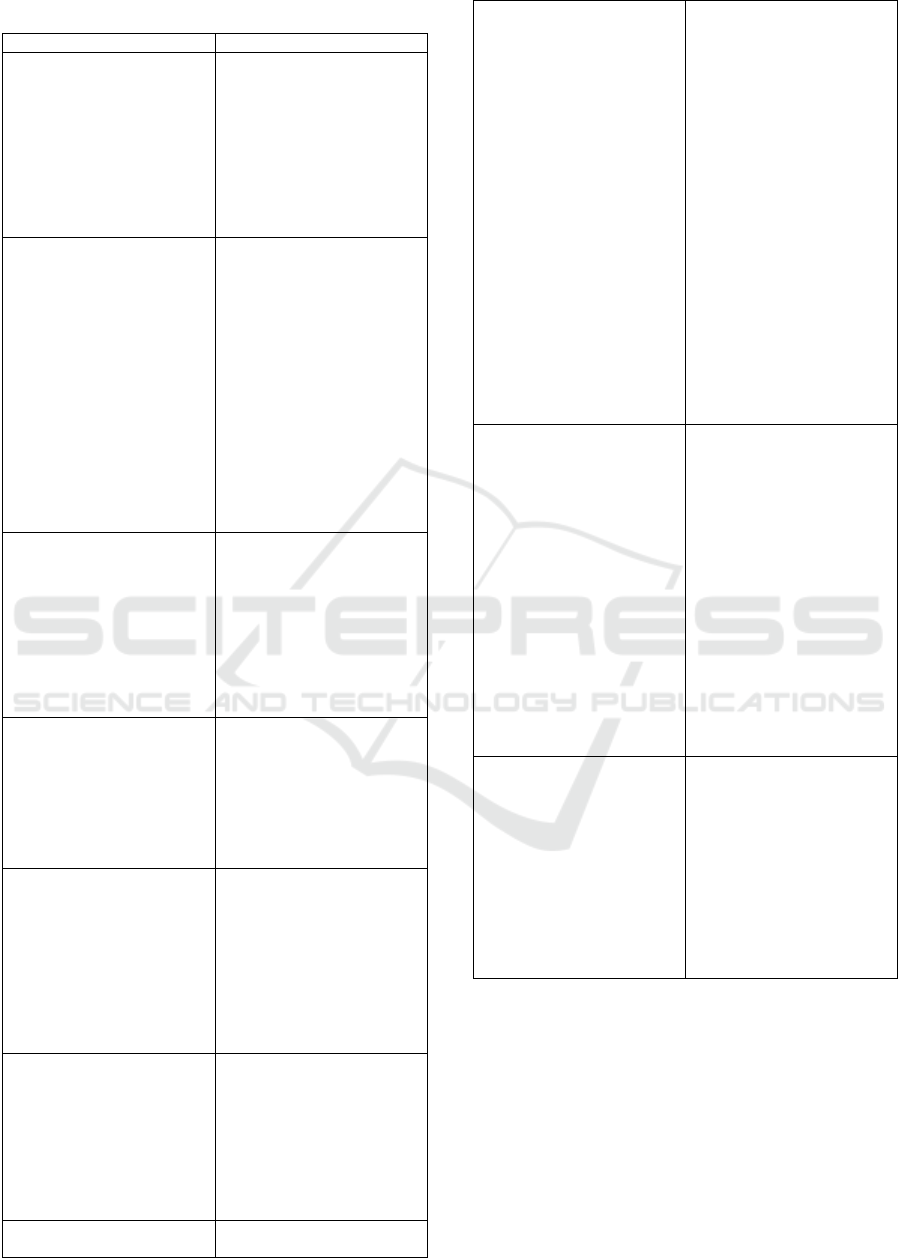

Table 1: Empirical data.

Data

gathering

method

Gathering

process

Data

Analysis

process

Observation

Two impact

assessment

seminars

06/2019 and

09/2019

Participate

observation

by two

researchers

Field notes

Interpretations

regarding the

situation made

by the

researchers

Content

Analysis

Interviews

7 interviews

09-11/2019

and 04/2020

by three

researcher

Transcribed

interviews

Content

analysis

Triangulatio

n by multiple

researchers

Circulation and

commentary

procedure

regarding

the masterplan

City’s official

commentary

system open

to all citizens

and specially

targeted

requests for

comments

Statement data

and City’s

response data

Content

Analysis

4 RESULTS

4.1 Findings through Design

Guidelines for Public Participation

Process, Case Lahti

We use the twelve tasks by Bryson et al (2013) to

analyze the empirical data from the Lahti case (see

Table 2). We observe through these lenses of public

participation process guidelines how city of Lahti has

designed and implemented the impact assessment

process and the tools thereof. We have used the three

classes I) assesses and design for context and purpose,

II) enlist resources and manage the participation, and

III) evaluate and redesign continuously to approach

the findings below. Based on the three classes the

findings reveal that in I) assessing and designing

context and purpose the process is mandatory, but

Lahti could/should focus on designing the context and

purpose more thoroughly to and with the stakeholders

and experts to reach significant outcome. In II)

enlisting resources and managing the participation the

infrastructure (platforms, data gathering, surveys,

facilitating etc) is on solid foundation but Lahti has

not yet achieved the best balance, solutions and

communication. When viewing III) the evaluations

and redesigning, it is obvious that the debriefing and

feedback must be enhanced.

Table 2: Findings.

Design outlines Case findings

I Design to address contexts

and problems

The public participation

process is needed for example

mandated or not, bottom -up or

perhaps combination

Fits the general and specific

context

Is based on clear understanding

of the challenge or problem

The publication participation

process in impact assessment

of master plan is mandated. It

fits the general and specific

context and the challenge is

that impact assessment of the

master plan needs to be done.

I Identify purposes and design

to achieve them clarify and

regularly revisit the purposes

and desired outcomes of the

participation process and

design and redesign

accordingly

The purpose is clear to the

architect and seems to be

clearer to most of the

participants from Lahti City,

but not clear to stakeholders

and or the experts. The

facilitators role needs to be

clarified. A joint meeting for

the experts, main working

group from the City before the

seminars would be advisable.

The “order” from the city of

Lahti was vague.

II Analyze and appropriately

involve stakeholders

Ensure that the design and

implementation of public

participation processes are

informed by stakeholder

analysis and involve (in a

minimum) key stakeholders in

appropriate ways across the

steps/phases of participation

process. Note that specific

stakeholders may be involved

in different ways at different

steps or phases of the process

Lahti used old participation

data for the impact assessment

and discussed the in some

research group the about the

new participants. The number

of new participants was

restricted and they were

handpicked from a large third

and fourth sector group. It

would have been beneficial to

note that some stakeholders

could have been involved

different way or at least that

they should have received more

background data to be able to

participate more usefully

Challenges in Public Participation and Collaboration: A Case Study in Finnish Environmental Decision-making

175

Table 2: Findings. (cont.)

Design outlines Case findings

II Establish the legitimacy of

the process

Establish with both internal and

external stakeholders the

legitimacy of the process as a

form of engagement and a

source of trusted interaction

among participants

The impact assessment process

was considered as itself a good

thing, but that it needs

developing. The legitimacy

was understood by the

stakeholders, however the

perception of how significant

the impact was, varied among

the stakeholders and experts

involved.

II Foster effective leadership

Ensure that the participation

process leadership roles of

sponsoring, championing and

facilitating are adequately

fulfilled

This seems to be clear for the

main work group, but there

needs more specific

communication to the

participants about the

leadership roles. The different

roles of the organizers could be

clearer to participants, for

example the role of the

facilitator was clear to all, but

the practical realization in the

seminars was in minor part,

merely time management

tasks. Also, the ownership of

the process was not clear to all

the participants

II Seek resources for and

through participation

Secure adequate resources and

design and manage

participation processes so that

they generate additional

resources – in order to produce

a favorable benefit-cost ratio

for the participation process

Yes, the infrastructure for this

process (the Lahden Suunta

Case) exists already and in this

impact assessment the

participants contributed to new

information and also to new

understanding in both sides of

the participants that is the

organizers and the

stakeholders.

II Create appropriate rules and

structures to guide the process

Create rules and a project team

to guide operation decision

making, the overall work to be

done and who gets to be

involved in decision making in

what ways

This was clear in the work

group, but could have been

communicated more openly

and clearly to the participants

II Use inclusive processes to

engage diversity productively

Employ inclusive processes

that invite diverse participation

and engage differences

productively

This was done to some extent.

The initial work group with the

research group discussed and

debated about the participants.

A list of participants was done,

however the attending rate of

the added participants was low.

How to encourage participants

to attend would be something

to consider next time.

II Manage power dynamics to

provide opportunities for

meaningful participation,

exchange and influence on

decision outcomes

The overall impression from

the interviews was that the

impact assessment seminars

were meaningful and that

participants could express their

opinions and views. The

seminars were characterized as

easy-going, friendly and

confidential.

II Use information,

communication and other

The communication to

participants varied depending

technologies to achieve the

purposes of engagement

Participation processes should

be designed to make use of

information, communication,

and other technologies that fit

with the context and the

purposes of the process

on their interest group (City

employees, stakeholders,

experts). This unequal

preparation was a challenge

and lead to difficulties in the

workshops as some

participants were more

knowledgeable for the

seminars than others. There

were plenty of materials in the

seminars “World café” tables,

but no time and chance to adapt

or even glance the material

through before attending the

discussions. Hence the value of

these materials was low.

Lahti had also planned to use a

web-based “Maptionnaire”

survey for the participants, but

due to internet attack against

Lahti City and the work groups

workload this did not take

place.

III Develop participation

evaluation measures and

evaluation process that

supports the desired outcomes

How to evaluate the public

participation effort

There was no survey for the

participants after the seminars.

The communication after first

seminar was adequate, but the

invitation or reminder for the

second seminar was inadequate

as it arrived in the afternoon of

the day prior to the second

seminar. After the second

seminar the participants

(including experts and

stakeholders) have not received

any communication from the

work group. To summarize it

seems that no evaluation

measures or evaluation process

plans have been made by the

working group in the Lahti city.

III Align participation goals,

purposes, approaches,

promises, methods, techniques,

technologies, steps and

resources

Participation process should

seek alignment across the

elements of the process.

Otherwise the chances of

miscommunication,

misunderstanding and serious

conflict increase

The impact assessment process

is primarily aligning with

goals, purposes etc. It needs

some modifications and

adjustments and

conceptualizing to be even

better.

4.2 The Concept of Collaborative

Governance in the Case Lahti

Considering the impact assessment process through

the lens of collaborative governance is complex, as

impact assessment is a mandatory phase by the law in

the master planning process. However, in the Case

Lahti could be seen several aspects of collaborative

governance, both in common benefits and challenges.

The distribution of power in the case was somewhat

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

176

clear, the master planning work group ran the process,

picked and invited the participants, and organized the

seminars. The participants experienced the

atmosphere open, friendly and confidential for

discussion, so the leadership could be considered

facilitative and empowering for the stakeholders. As

a downside, all the participants were not handed the

same amount of information beforehand, which put

the participants in unequal position and affected the

balance between the roles, as well as the efficiency

and effectiveness of the process. Whereas the roles

and the process were clear to the master planning

work group, there was some obscurity amongst the

participants of the roles in the process, and of the

process itself. Also, the purpose of the impact

assessment and the aims of the seminars were not

clear to all. Despite the fact, that the communication

was experienced open at the seminars, there would be

needed some improvement in communication by the

leaders regarding the participation process itself,

setting rules for how the process runs and

communicating them to stakeholders. Creating clear

frames for the collaborative actions and sharing

information equally amongst all participants,

improves the equality and balance between different

roles and stakeholders, and prevents experiences of

the process being seeming or injustice.

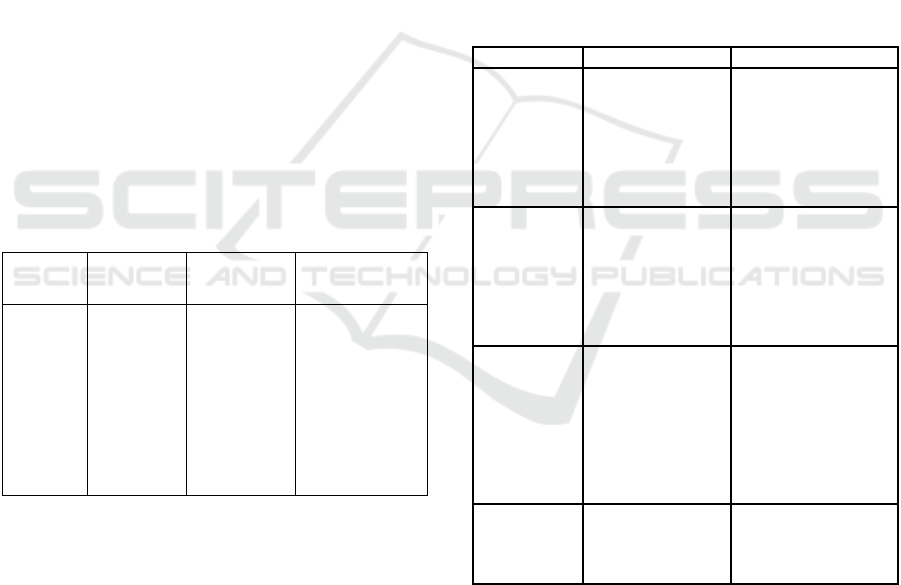

Table 3: Findings of collaborative governance.

Distribution

of power

Balance of

roles

Communication

Working jointly

towards solutions

by learning

Somewhat

clear, the

leadership is

facilitative

and

empowering,

experiences

of seemingly

process

The roles were

not fully clear

to all, and

sharing

different

amounts of

information

and lacking

communicatio

n set imbalance

between roles

Experienced

open, but was

lacking in term

of informing

about the aims

and purpose,

roles and phases

of the processes

Aims, purposes and

the processes were

not clear to all,

which indicates not

working towards

jointly set goals.

Also, there was so

evaluation,

assessment or

reflection for the

participants

One of the most important tools and at the same

time outcomes of the collaborative governance

process is social learning. Social learning enables

building up the social and economic capacity, where

the stakeholders are increasingly capable to solve

more and more complex issues. However, the

learning process needs to be facilitated by open

communication, sharing information and knowledge

flow, but also by setting joint aims and reflecting the

actions towards them. At the same time, involving the

stakeholders in setting the goals, working jointly

towards them and then reflecting, engages the

stakeholders to the process and creates shared

ownership, which feeds sharing power and taking

responsibility further. Currently, the participants

were not asked feedback of the seminars nor asked to

reflect their participation in the seminars or the

process, which can be seen hindering learning and

developing the collaborative process further, but also

preventing to optimize the impact assessment process

itself.

4.3 Summary of the Findings

We used two perspectives to study the Case Lahti i.e.

Public Participation process framework and

collaborative governance studies to try to understand

and identify the challenges in the collaborative impact

assessment process of Lahti. The findings were very

similar from both angles and we have concluded them

in Table 4.

Table 4: Summary of the findings.

Challenge Manifestation Proposed solution

Knowledge

sharing

Unequal distribution

of materials,

accessibility of

materials,

communication

problems; late,

insufficient or hasty

Increase awareness

and implement a

knowledge sharing

supporting culture

including technical

systems such as map

apps and platforms

Roles,

distribution of

power and

value

(organizers

and

participants)

Roles and

distribution of

power was not clear

to all participants

and lead to some

challenges

Open communication,

clear and well-defined

responsibilities,

authority and impacts

for all

Overview of

the process

Reshuffle in

working group,

what part of the

process is impact

assessment, how it

continues, what is

needed from the

participants

Schemes for

knowledge sharing,

especially tacit

knowledge,

communication and

planning

Learning

lessons

No feedback or

evaluations

Implement a procedure

for debriefing and

feedback and

communicate

5 CONCLUSIONS

Stakeholder engagement through participatory

approaches is claimed to be the remedy when tackling

contemporary complex environmental challenges

(Reed et al, 2018) - when succeeded, the results may

exceed any outcome the actors would have able to

reach alone (Emerson et al, 2012), but on a downside

Challenges in Public Participation and Collaboration: A Case Study in Finnish Environmental Decision-making

177

a failure might have far-reaching consequences.

(Reed et al, 2018; Irvin & Stansbury, 2004; Ansell &

Gash, 2008). The initiating actor for collaboration

does not always foresee the outcome, and there is no

way to guarantee the collaboration to succeed (Reed

et al, 2018; Gaventa & Barrett, 2012). Therefore, the

participative actions need to be purposeful with well-

defined aims and cautious planning, and rather

involving the stakeholders with a full intention of

meaning and true distribution of power. However, it

is up to the actors within the participation process to

formulate their joint rules, roles and ways of working,

as well as setting goals for collaboration, and through

open communication and reflection adjust the process

to ensure working jointly and purposefully towards

the aims. (Bryson et al 2013; Irvin & Stansbury,

2004).

Communication and knowledge sharing can be

considered critical points in creating a powerful and

functional collaborative participation process.

“Communications usually fails, except by accident”

(Wiio, O, 1978) is a “communication law” created by

the Finnish academic Osmo Wiio on 1970s.

Inequality in communication and information sharing

can easily lead to even severe challenges in the

process, fortunately this can be tackled by

acknowledging the level of difficulties in

communication, increasing awareness of

communication and implementing a knowledge

sharing supporting culture.

Even though the process is iterative and adaptive

by nature, to gain a functional, ongoing and active

collaboration the process needs to be conceptualized.

Open communication, knowledge sharing culture,

constant planning, feedback and debriefing are core

factors that need to be taken account in a

conceptualized process. A conceptualized process

can then be utilized as a template in various contexts

and for different purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Strategic

Research Council’s Project CORE.

REFERENCES

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative Governance

in Theory and Practice. Journal of Public

Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571.

Batory, A. & Svensson, S. (2019). “The Fuzzy Concept of

Collaborative Governance: A Systematic Review of the

State of the Art.” Central European Journal Of Public

Policy 13.2: 28–39. Web.

Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of

knowledge generation, bridging organizations and

social learning. Journal of Environmental Management

90, 1692–1702.

Brinkerhoff, D. W., & Azfar, O. (2006). Decentralization

and community empowerment: Does community

empowerment deepen democracy and improve service

delivery?. Washington, DC: Office of Democracy and

Governance, USAID

Bryson, J., Quick, K., Slotterback, C. & Crosby, B. (2013).

Designing Public Participation Processes. Public

Administration Review, 73(1), 23–34.

CORE (2018). Collaborative remedies for fragmented

societies – facilitating the collaborative turn in

environmental decision-making – CORE.

http://www.collaboration.fi/EN/.

Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis

process. (2008). Journal of Advanced Nursing., 62(1),

107–115.

Elinkeino-, Liikenne-, ja Ympäristökeskus ELY. (2017).

Osallistun kaavoitukseen, kuntalaisen opas. Accessed

23.6.2020. Available at:

https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/130881/

Opas%205%202016.pdf?sequence=1

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T. & Balogh, S. (2012). An

Integrated Framework for Collaborative Governance.

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory,

22(1):1

Fielding, N., Fielding, J. (1986). Linking data. London:

SAGE.

Gaventa, J. & Barrett, G. (2012). Mapping the Outcomes of

Citizen Engagement. World Development, 40(12), p.

2399-2410.

Godenhjelm, S., & Johanson, J.-E. (2018). The effect of

stakeholder inclusion on public sector project

innovation. International Review of Administrative

Sciences, 84(1), 42–62.

Holbrook, M. B., 2006. Consumption experience, customer

value, and subjective personal introspection: An

illustrative photographic essay. Journal of Business

Research, 59(6), 714-725.

Hotte, N., S. Kozak, R. Wyatt. (2019). How institutions

shape trust during collective action: A case study of

forest governance on Haida Gwaii. Forest Policy and

Economics 10, 1—11.

Irvin, R. A., & Stansbury, J. (2004). Citizen participation in

decision making: is it worth the effort? Public

administration review, 64(1), 55-65

Lahti. (2019). Osallistumis- ja arviointisuunnitelma.

Lahden suunta. Accessed 23.6.2020. Available at:

https://www.lahti.fi/paatoksenteko/strategia-ja-

talous/lahden-suunta

Leino, J. (2019). Yhteishallinnan mahdollisuuksista

Suomessa. Ympäristöpolitiikan ja –oikeuden vuosikirja

2019, 346—379.

Mäntysalo, Raine et al. “The Strategic Incrementalism of

Lahti Master Planning: Three Lessons.” Planning

Theory & Practice 20.4 (2019): 555–572. Web.

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

178

Palomäki, J. (2018) Yleiskaavoituksen uusimpia tuulia

Lahdessa, Oulussa, Tampereella ja Helsingissä vuonna

2017. Teoksessa Hastio, Pia; Korkala, Paula; Laitio,

Matti; Manninen, Rikhard; Paajanen, Paula; Palomäki,

Johanna. Ympäristöministeriön raportteja 2/2018.

Helsinki: Ympäristöministeriö: 14-23

Palomäki, Johanna (2013). Lahden yleiskaava. Teoksessa

Koivu, Veli-Pekka, Korkala, Paula, Laitio, Matti,

Manninen, Rikhard, Paajanen, Paula, Palomäki,

Johanna, Rossi, Leena ja Vänskä, Veikko (toim.):

Yleiskaavoituksen uusia tuulia. Ympäristöministeriön

raportteja 10/2013. Ympäristöministeriö, Helsinki 9-

16. 5), 640-654.

Paunu, Annamaija, Vuori, Vilma, Helander, Nina,

Collaborative Processes in Environmental Decision-

Making: Fact or Fiction?, 7th biennial International

Symposium on Cross-Sector Social Interactions (CSSI

2020), virtual conference.

Reed, M., Vella, S., Challies, E., de Vente, J., Frewer, L.,

Hohenwallner-Ries, D., Huber, T., Neumann, R.,

Oughton, E., Sidoli del Ceno, J., & van Delden, H.

(2018). A theory of participation: what makes

stakeholder and public engagement in environmental

management work?: A theory of participation.

Restoration Ecology, 26, S7–S17.

Sotarauta, M. (2010). Regional development and regional

networks: The role of regional development officers in

Finland. European Urban and Regional Studies, 17 (4),

p. 387-400

Tuomi, J., & Sarajärvi, A. (2018). Laadullinen tutkimus ja

sisällönanalyysi (Uudistettu laitos.). Helsinki: Tammi.

Tuomisaari, J. (2019). Epävarmuuden edessä: kuntien

strateginen kaavoitus joustavana käytäntönä.

Tampereen yliopisto

Wiio, Osmo A. (1978) Wiion lait - ja vähän muidenkin.

Espoo, Weilin + Göös.

Challenges in Public Participation and Collaboration: A Case Study in Finnish Environmental Decision-making

179