Industry-oriented Digital Transformation in Universities to Facilitate

Knowledge Transfer

Claudia Doering

a

and Holger Timinger

b

Institute for Data and Process Science, University of Applied Sciences, Landshut, Germany

Keywords: Enterprise Modeling, Knowledge Management, Modeling for Digitalization, Third Mission, Knowledge

Transfer, Digital Transformation.

Abstract: The industry faces nowadays major challenges in creating new and innovative business models. Especially

small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) lack own research departments and qualified personnel for new

technologies and business models. Simultaneously, SMEs are often unsure, if their needs are understood and

addressed by universities and hesitate to contact them. Actually, many universities do have very relevant

technologies for such companies and strive for an increase in joint research and transfer activities. However,

universities must change and simplify their inner structures in order to accomplish a structural embodiment

of transfer and become more customer-oriented and quicker.

1 INTRODUCTION

The last decades have been characterized by a strong

shift in the way of how universities interact with their

environment. Besides their mission to teach and to

conduct research, a third mission is gaining

importance: knowledge transfer (Roessler et al.

2015). This transfer is described in multiple

theoretical frameworks, like the concept of

“entrepreneurial universities” (Clark 1998), the

“Triple Helix” (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 2000),

“Mode 2” (Gibbons et al. 1994) or the “Quintuple

Helix” (Carayannis and Campbell 2012). All of these

concepts comprise the idea that research, which is

conducted within universities, should be

communicated and transferred to the society and the

economy. In this way, universities are no longer seen

as “ivory towers” in which research is cut off from the

rest of the society, but rather as institutions with a

distinctive knowledge transfer (Doering and Seel

2019). Knowledge transfer has to be related to the

transfer of tactic knowledge, which is an important

function of universities (Ritesh Chugh, Santoso

Wibowo and Srimannarayana Grandhi 2015). Tactic

knowledge was first described by Polanyi (1958), but

nowadays this concept is of fundamental importance

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3727-8773

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7992-0392

for multiple knowledge management approaches

(Firestone and McElroy 2003). Tactic knowledge

cannot be codified, is generally implicit in its nature

and difficult to access (Busch 2008).

The mission to transfer expertise out of the

universities into to society relates mostly to a

pronounced knowledge transfer. The transfer of

knowledge has traditionally been defined as an

interface between science and economy (Froese

2014). Nowadays, it can be seen as all forms of

communication between an expert (sender) and a

layperson (receiver), whereby the transfer partners

can be individuals or collectives (Pircher 2014; Thiel

2002). Various definitions of knowledge transfer

constitute it as a synonym to the third mission of

universities (Henke et al. 2017; Noelting et al. 2018).

Currently, this third mission as knowledge transfer

between universities and the society is gaining

increasingly relevance due to the ongoing

digitalization of all areas of life. Digital

transformation has been an issue to many publications

and research as it has become a major research and

engineering challenge worldwide

(Wolan 2013).

Nevertheless, the economy is experiencing a

continuing pressure to act because of the

digitalization and strong technological developments

of mainly all business sectors. The speed of

212

Doering, C. and Timinger, H.

Industry-oriented Digital Transformation in Universities to Facilitate Knowledge Transfer.

DOI: 10.5220/0010144402120218

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2020) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 212-218

ISBN: 978-989-758-474-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

technological change and an increasing international

competition requires also smaller or medium-sized

enterprises (SMEs) to engage in digitalization.

Especially these companies face the challenge to

develop new business models and/or products, as they

often lack own research and development

departments. Unfortunately, SMEs often hesitate to

contact universities, because of their preconceptions

that universities do not take their needs seriously or

do not have solutions, which are applicable for SMEs.

They typically need quick answers to urgent

challenges, which can be implemented with very

limited resources.

Universities have understood this need and are

now engaging even more in knowledge transfer

activities than prior to the digital transformation.

However, transfer has to be seen as a bidirectional

process, as also universities have to understand the

issues and needs of the companies and therefore can

also learn from the digital transformation of the

economy and the society.

Universities often have a deep understanding of

the processes of digitalization due to their experts and

research activities. Simultaneously, their own inner

structure still lacks digital work processes. Internal

work processes within universities are often only

modelled roughly to define and not to digitize work

procedures. The need for digitalization of universities

therefore arises not only from the constraint to

conduct third mission activities and the demand from

companies to engage in a deeper knowledge transfer,

but also from the need to digitize their inner work

procedures.

Digitization can be defined as the transfer of

analogous extends to discrete (digital) values, in order

to safe or process this data electronically (Löbbecke

2006). Digitalization goes even further and can be

describes as the use of digital technologies which can

even change a business model. Therefore, it can be

seen as the process of moving to a digital business

(Bloomberg 2018). Recently also concepts of a

“Digital Revolution” or ”Digital Transformation”

arise, which describe the process of change in society

and economy caused by digitalization (Schallmo et al.

2018). There are multiple benefits of digitalization,

which not only apply to companies, but are also

relevant to universities. Digitalization requires the

extraction of tacit individual, interpersonal or

organizational knowledge from universities to

support external partners in the digitalization

activities. Therefore, the universities themselves have

to conduct a digital transformation within their own

organization. This article distinguishes between the

digital transfer product and the digital transfer

process of universities, which is needed to facilitate

collaboration between them and external partners.

Although the digital transfer product (e.g. the support

of universities for society/economy in digitalization)

is of great importance, this article focuses on the

digital transfer process of universities.

Therefore, a framework for digital transformation

within universities will be proposed to enable these

institutions to engage in knowledge transfer activities

with external partners, who face digitalization

challenges on their own.

Therefore, the following research questions arise:

RQ1. What are the needs for digitalization of

knowledge transfer as part of the third mission of

universities?

RQ2. How can the process of digitalization in

universities be presented in a structured framework to

facilitate knowledge transfer?

The goal is to propose a systematic process for

digitalization at universities in order to qualitatively

and quantitatively increase knowledge transfer with

the economy and society.

This article is divided in the following sections: at

first, the relevant research methodology is outlined.

RQ1 is then answered in the following section

Reasons for Digitalization in Universities. The next

sections covers RQ2 and demonstrates the process of

digitalization in universities in a structured

framework. An overview of the evaluation of the

results and an outlook completes this contribution.

2 METHODS

A research methodology is determined by the chosen

research questions and the research aim. As the

research questions of this article aim to create new

methods and artefacts, the research methodology

follows the design science research paradigm by

H

EVNER et al. (2010). To ensure that the proposed

process for digitalization at universities displays the

reality adequately, expert interviews were conducted

(Meuser and Nagel 2009). The experts were chosen

because of their responsibility and experience in

knowledge transfer projects. To follow the guidelines

of Design Science, the iterative search process will be

ensured through the comparison of deductive and

inductive research findings (Hevner and Chatterjee

2010). The purpose of this article is to present the

research findings and to communicate them in this

way to the target audience.

Industry-oriented Digital Transformation in Universities to Facilitate Knowledge Transfer

213

3 NEEDS FOR DIGITALIZATION

IN UNIVERSITIES

Digitalization at universities addresses mainly the

internal processes and structures within these

institutions. As mentioned above, the impulse for

digitalization arrives both from the inside of

universities, but also from the outside

(economy/society). To adequately assess this

situation, the external and internal needs for

digitalization are shown in table 1. The list was

created as a result of expert interviews and research

within the project TRIO (Transfer and Innovation

East-Bavaria), without making claims in being

complete. The interviews were conducted in this

cross-university initiative of six universities in

Germany (TRIO). These universities have initiated a

joint alliance in January 2018. All chosen experts are

employees in technology and knowledge transfer

offices, research funding departments, finance and

legal departments. The experts were chosen due to

their responsibility and experience in knowledge

transfer projects and their possession of privileged

information (Meuser and Nagel 2009). The

interviews were conducted in a partly structured

manner, to allow for a generation of interpretive

knowledge (Przyborski and Wohlrab-Sahr 2014). In

total 8 expert interviews were conducted with a length

of 40min each. The expert interviews started with a

preliminary talk and a self-presentation of the expert.

Then the area of interest was introduced by an open

question (e.g. “Please explain to me, why your

department in this university should engage more in

the process of internal digitalization?”, “What do

you think could improve within your department in

regards to internal digitalization?”). To generate

deeper insights, the experts were asked to name

examples for e.g. internal needs for digitalization.

To not only ask for facts, the experts were

requested to interpret their statements (e.g. “Why can

internal digitalization in universities improve the

handling of transfer projects?”). Finally, the experts

were asked to theorize their statements and to show

on a meta level, what needs for digitalization the

whole university could have. The results of the expert

interviews are displayed in table 1.

External needs for digitalization arise mainly in

the economy and the society. When collaborating

with universities, these stakeholders can demand

support in digitalization issues. Although this relates

in the first place to the digital transfer product, it can

lead to a digitalization process within the universities,

as they can learn from the digital transformation of

the economy and the society. This digital change

opens up new potential for universities to develop

their offerings and structures.

There are various internal needs for digitalization

as well. They include the need for a faster and easier

managing of transfer projects. This is mainly due to

the institutional inertia of the universities, which

results from their governance and administrative

structure. Strategy and development processes are

often too long-winded and innovative ideas from

students and staff are often not heard.

Table 1: Needs for digitalization of knowledge transfer as

part of the third mission of universities (cf. RQ1).

External Needs (from

economy/society)

Pull for digitalization from

external partners

Faster and easier knowledge

transfer

Understanding and handling

of needs

Internal Needs

(within universities)

Faster and easier knowledge

transfer

Improvement of internal

services

Structured documentation and

simplified reutilization of

processes

Streamlining of processes

Rationalization

Reduction of errors

Improvement of quality

Lower process costs

Improvement of transparency

Up-to-date teaching contents

Up-to-date teaching methods

Safeguarding the future of

research and transfer at

universities

A faster and easier handling of transfer projects

can be realized with the usage of a structured

documentation and streamlined processes for the

realization of transfer projects. This can lead to an

improvement of the services of universities, as the

quality and transparency of these processes will

increase through a digital handling of transfer

projects. A quick reply to external inquiries regarding

new transfer activities is also an important success

factor for the future. Universities are more and more

competing for external funding, which often is related

to transfer activities. Thus, a quick response, which is

facilitated by digital processes and workflows, can be

considered to be crucial to increase speed.

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

214

The digitalization can also lead to lower process costs

for the universities, as the rationalization of the

processes may lead to a reduced amount of errors. To

persist as a competent partner for the economy and

society, universities have to keep up with the times

and incorporate a digital transformation to safeguard

their own future of research and transfer.

4 DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION

IN UNIVERSITIES TO

FACILITATE KNOWLEDGE

TRANSFER

Attractive digital services are a central prerequisite

for universities competing for the best projects,

scientists, students and employees in research and

administration (Gilch et al. 2019). Due to the high

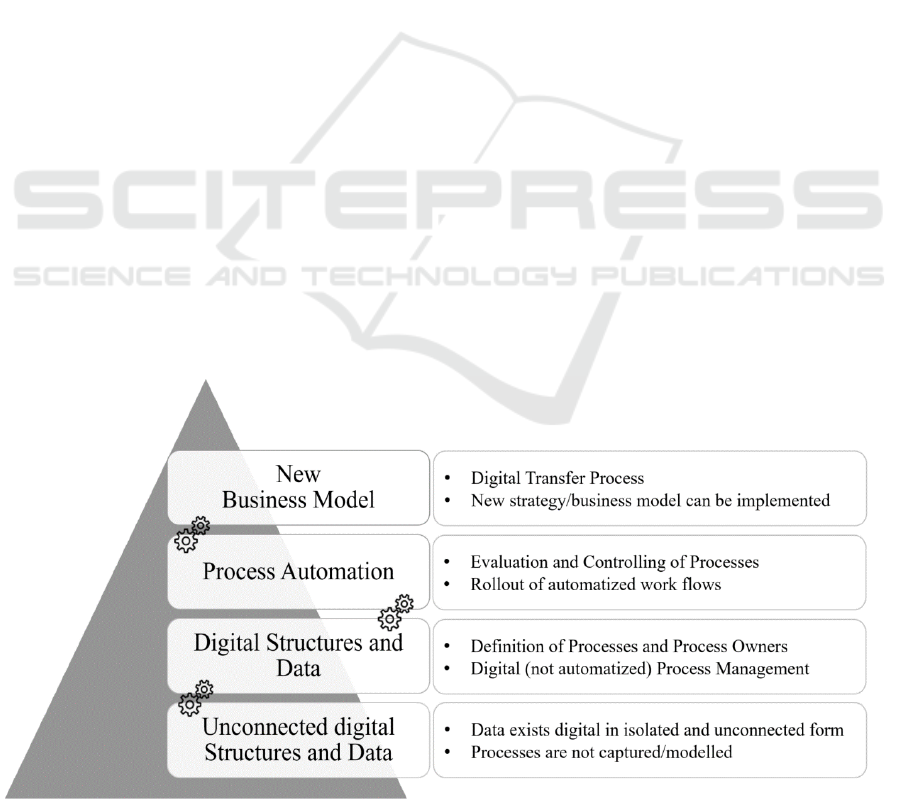

complexity of the digital transformation, the

framework shown in figure 1 (cf. RQ2) was created.

This framework represents an artefact of the Design

Science process. The intended purpose of this

framework is to facilitate digitalization of knowledge

transfer in universities.

The digital transfer process within universities

begins with the usage of isolated digital structures and

data. Processes in the administration are not captured

or modelled and all data just exists in an isolated

digital form, which is not linked to workflows, yet.

To reach the next stage of digital transformation,

these processes and data need to be transferred into a

comprehensive digital structure. The information is

converted over several stages into a digital signal.

Yet, there is no content related change within the data

or processes. This allows for a process management,

which is digital but not automatized. At this step the

processes need to be newly defined, modelled and

responsibilities have to be assigned. The previous

isolated processes and procedures are not necessarily

transferred into the next stage. Instead, they need to

be rethought and potentially completely implemented

from scratch in order to meet the requirements of

digitalized processes and their customers. This is

often accompanied by a restructuring of the

organization of the university: responsibilities and the

roles of employees are being changed in the course of

the digital transformation. Old areas of responsibility

are being automated and new areas of responsibility

arise. For example, the calculation of a standard

transfer projects can be automatically be generated.

This leaves more time for project support and the

initiation of new transfer collaborations. The

comprehensive digitization requires standardization

of the processes, to simplify their automation. At this

stage also a digital evaluation and controlling of the

processes is possible. As processes and procedures

are increasingly being mapped by digital,

automatized workflows, the content work can now be

carried out digitally. To no longer just react to the

digital transformation, but to actively shape it, it is

essential that all processes are matched through clear

responsibilities, sustainable decision-making

structures and participation opportunities. In addition

to the commitment of the university management by

actively shaping strategic development, the university

must also establish sustainable decision-making

structures

between the university management and

Figure 1: Framework for digital Transformation in Universities (cf. RQ2).

Industry-oriented Digital Transformation in Universities to Facilitate Knowledge Transfer

215

the faculties/departments and define responsibilities

at the various levels. Obviously, this point can be hard

to implement in practice, as faculties/departments and

researchers have a high degree of autonomy, whereas

university administrations are generally

hierarchically structured with clear procedural

approaches. Nevertheless, this internal collaboration

can be simplified through digital workflows, as

communication between the administration and the

knowledge carriers can be facilitated. This can also

help to overcome the silo mentality, which exist in

some universities (Bolden et al. 2009; Friedman and

Weiser Friedman 2018). Also, competences and

responsibilities can be displayed more transparently.

It is important that a viable continuation of the digital

development and implementation is also ensured in

the case of personnel changes, especially in the

university management, by means of role descriptions

that are detached from people. In addition, all

stakeholders as well as the central institutions and the

administrative bodies responsible for transfer and

teaching must be involved in the digital development

as far as possible.

As a final step in the digital transformation in

universities, the digitalization can enable an

occurrence of new business models or strategies for

universities. Digitalization can not only support

universities in safeguarding their future in research

and transfer, but also reinforces them to understand

and handle the needs from external partners better to

allow for faster and easier knowledge transfer.

5 EVALUATION

The design science process aims to create artifacts to

solve practical problems (Hevner and Chatterjee

2010). One of the core activities of the Design

Science Process is the evaluation of the key findings

and the proof and justification of the artifacts. The

evaluation of the framework for digital

transformation of universities is going to be

conducted in a collaboration of six German

universities, which have merged to enable deeper

knowledge transfer with society and economy. As the

digitalization process is going to last over a long

period of time, the evaluation of this model will be

conducted in the meantime. Although the process of

digitalization is already initiated within those six

collaborating universities, it will take a serious

amount of time to fully implement it. Therefore, a

preliminary evaluation of this model was conducted.

The aim of this evaluation was to find out, whether all

identified external and internal needs are displayed

correctly through the framework for digital

transformation in universities.

5.1 Evaluation of External Needs

The needs from economy and society refer mostly to

an easier and faster handling of transfer projects and

their preconception that universities do not take their

needs seriously or do not have solutions, which are

applicable for SMEs. Especially, SMEs tend to

hesitate to contact universities, as they often need

quick solutions for their urgent problems. A practiced

digital transfer process within universities can ensure

a comprehensive handling of these needs, as defined

and automatized workflows allow for a faster internal

processing within the administration of universities.

5.2 Evaluation of Internal Needs

The needs from stakeholders within universities are

numerous and range from the organization and

implementation of transfer projects to the

safeguarding of the future of research and transfer.

Administrational and organizational issues within

universities can be reduced through defined and

automated workflows. A digital transfer process can

improve the internal and external services of

universities to make them an even more competent

and desired project partner. Process automation can

also facilitate the evaluation and controlling of

internal processes, which can lead to improved

internal services. Another indicator for the

correctness of the framework is that it provides a

general overview of the digital transfer process and

acts as a means for the rationalization and

streamlining of administrative processes. As

processes need to be defined and modelled very

clearly to automatize them in workflows, the

framework also allows for lower process costs, a

structured documentation and a higher process

transparency.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

OUTLOOK

In this article, the two research questions RQ1 and

RQ2 have been answered. The first question dealt

with the needs for digitalization of knowledge

transfer as part of the third mission of universities.

With the help of expert interviews, multiple external

and internal needs could be identified and structured

(cf. RQ1). It was found that the digital transfer

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

216

process needs to be displayed in a structural and

procedural framework. The created artefact, the

framework for digital Transformation in Universities,

shows the digital transfer process (cf. RQ2). The

framework was developed in a cross-university

initiative of six universities in Germany. In the past,

each university developed its own best practices and

resulting processes. The framework helps to reflect

the own degree of digitalization maturity and

facilitates the improvement of the own process map

regarding digitalization and automation.

However, the digital transformation is a

challenge, which holds true also for heterogeneous

and diverse organizations like universities. On the

one hand, the competition for research grants, transfer

projects, industry contacts, and students is increasing.

On the other hand, universities are used to manual and

at least partly long-lasting processes.

A structured approach to the digital

transformation as presented in this paper can help to

compete successfully, to implement reliable and fast-

automated processes, which facilitate transfer, and

saving resources for tasks which cannot be

automatized. Future work will include a deeper

testing of the suggested framework to assess its

efficacy. Furthermore, practical results of the

application of the structured approach to the digital

transformation will be presented in detail.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The transfer project "Transfer and Innovation East-

Bavaria" is funded by the "Innovative University of

Applied Sciences" East-Bavaria 2018 – 2022

(03IHS078D).

REFERENCES

Bloomberg, J. (2018) ‘Digitization, digitalization and

digital transformation: confuse them at your peril’,

Forbes.

Bolden, R., Petrov, G. and Gosling, J. (2009) ‘Distributed

Leadership in Higher Education’, Educational

Management Administration & Leadership 37: 257–77.

Busch, P. (2008) Tacit knowledge in organizational

learning, Hershey, Pa: IGI Global (701 E. Chocolate

Avenue Hershey Pennsylvania 17033 USA).

Carayannis, E. G. and Campbell, D. F. J. (2012) Mode 3

knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation

systems. 21st-century democracy, innovation, and

entrepreneurship for development, New York:

Springer.

Clark, B. R. (1998) ‘The Entrepreneurial University:

Demand and Response’, Tertiary Education and

Management: 5–16.

Doering, C. and Seel, C. (2019) ‘Collaborative Knowledge

Management in University Alliances with Information

Models’, in: INSTICC (Hg.) 2019 – 11th International

Conference on Knowledge, pp. 243–249.

Etzkowitz, H. and Leydesdorff, L. (2000) ‘The dynamics of

innovation: from National Systems and ‘‘Mode 2’’ to a

Triple Helix of university–industry–government

relations’.

Firestone, J. M. and McElroy, M. W. (2003) Key issues in

the new knowledge management, Boston, MA,

Hartland Four Corners, Vt: Butterworth-Heinemann;

KMCI Press.

Friedman, H. H. and Weiser Friedman, L. (2018) ‘Does

Growing the Number of Academic Departments

Improve the Quality of Higher Education?’,

Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource

Management 6: 96.

Froese, A. (2014) ‘Wissenschaftliche Güte und

gesellschaftliche Relevanz der Sozial- und

Raumwissenschaften’, Handreichung für Wissenschaft,

Wissenschaftspolitik und Praxis, WZB Discussion

Paper.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S.

and Scott, P. (1994) The New Production of

Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in

Contemporary Societies.

Gilch, H., Beise, A.S., Krempkow, R., Müller, M.,

Stratmann, F. and Wannemacher, K. (2019)

‘Digitalisierung der Hochschulen: Ergebnisse einer

Schwerpunktstudie für die Expertenkommission

Forschung und Innovation’, Studien zum deutschen

Innovationssystem.

Henke, J., Pasternack, P. and Schmid, S. (2017) Mission,

die dritte. Die Vielfalt jenseits hochschulischer

Forschung und Lehre: Konzept und Kommunikation

der Third Mission, Berlin: BWV Berliner

Wissenschafts-Verlag.

Hevner, A. R. and Chatterjee, S. (2010) ‘Design Research

in Information Systems Theory and Practice’,

Integrated Series in Information Systems Volume 22.

Löbbecke, C. (2006) ‘Digitalisierung - Technologien und

Unternehmensstrategien’, in: Handbuch

Medienmanagement, Berlin [u.a.]: Springer, pp. 357–

373.

Meuser, M. and Nagel, U. (2009) ‘Das Experteninterview -

konzeptionelle Grundlagen und methodische Anlage’,

in: S. Pickel, G. Pickel, H.-J. Lauth and D. Jahn (eds)

Methoden der vergleichenden Politik- und

Sozialwissenschaft, 1st edn.

Noelting, B., Demski, N., Kräusche, K., Lehmann, K.,

Molitor, H., Pape, J., Pfriem, A. and Walk, H. (2018)

‘Nachhaltigkeitstransfer von Hochschulen’,

Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kultur

Land Brandenburg; HochN.

Pircher, R. (ed.) (2014) Wissensmanagement,

Wissenstransfer, Wissensnetzwerke. Konzepte,

Methoden, Erfahrungen, 2nd edn: Publicis.

Industry-oriented Digital Transformation in Universities to Facilitate Knowledge Transfer

217

Przyborski, A. and Wohlrab-Sahr, M. (2014) Qualitative

Sozialforschung. Ein Arbeitsbuch, 4th edn, München:

Oldenbourg.

Ritesh Chugh, Santoso Wibowo and Srimannarayana

Grandhi (2015) ‘Mandating the Transfer of Tacit

Knowledge in Australian Universities’, Journal of

Organizational Knowledge Management.

Roessler, I., Duong, S. and Hachmeister, C.-D. (2015)

‘Welche Missionen haben Hochschulen?’, CHE

gemeinnütziges Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung.

Schallmo, D., Reinhart, J. and Kuntz, E. (2018) Digitale

Transformation von Geschäftsmodellen erfolgreich

gestalten. Trends, Auswirkungen und Roadmap,

Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Thiel, M. (2002) Wissenstransfer in komplexen

Organisationen. Effizienz durch Wiederverwendung

von Wissen und Best Practices: Gabler Edition

Wissenschaft.

Wolan, M. (2013) Digitale Innovation. Schneller,

wirtschaftlicher, nachhaltiger, 1st edn, Göttingen:

Business-Village.

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

218